| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Fireman and bellhop |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32488624 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “C,” 81st Chemical Battalion |

Early Life & Family

Roy Alonzo Baldwin, Jr. was born on December 12, 1915, at 433 East 6th Street in Wilmington, Delaware. He was the fifth child of Roy Alonzo Baldwin, Sr. (a steamfitter or plumber, 1887–1918) and Susan Agnes Baldwin (née McConnell, later Alexander, 1891–1982). Baldwin was baptized on October 24, 1916, at the First Presbyterian Church of Wilmington.

Tragedy was a constant companion to the Baldwin family. Of his parents’ six children, only Baldwin and his older brother, Marvin Harold Baldwin (1914–2001) lived to adulthood. His three oldest siblings died as infants, as did a younger brother. Baldwin was likely living at 517 East 6th Street, where his younger brother, John Baldwin, was born prematurely and died the same day, January 23, 1918. The 1920 census suggests it may have been the home of Baldwin’s paternal grandparents, Alonzo F. Baldwin (1854–1934) and Amelia Baldwin (née Sparks, 1861–1941).

Later that year, on October 13, 1918, during the Great Influenza Pandemic, Baldwin’s father, by then working as a plumber for American Car & Foundry, died at 517 East 6th Street. Baldwin was just two years old when his father died. The Evening Journal reported on October 25, 1918, that Baldwin’s father and employees had averaged $109 per employee in liberty bonds (war bonds for World War I):

As showing the real American spirit of the men, Roy Baldwin, employed in the tin shop, in the early days of the campaign subscribed to a $100 bond. A few days afterward he died of influenza. His fellow-workmen immediately agreed to complete his payment of $96 for the bond, and this will be presented to Mrs. Baldwin.

Baldwin was still living at 517 East 6th Street when he recorded on the census on January 3, 1920, living with his mother, brother, paternal grandparents, and two uncles. Balwin was not recorded in any known 1930 census records. Although he was only 14, he was not listed as living with his mother, who had remarried c. 1924 to Levin Bradley Bryan Alexander (also known as Bradley B. Alexander, 1891–1940). Similarly, he was not listed as living with his brother, who was living with an aunt and uncle, nor with his paternal grandmother. The rest of his grandparents were already deceased.

Baldwin attended Wilmington High School, but it is unclear if he graduated. The 1940 census stated he had completed four years of high school, but his enlistment data card stated he had completed three years.

Baldwin was working as a bellman when he married Catherine Agnes Nowak (Katherine in some records, 1915–1990) in Wilmington on the afternoon of September 11, 1936. The couple had one child, Janice Elizabeth Baldwin (later McKnight, 1936–2000).

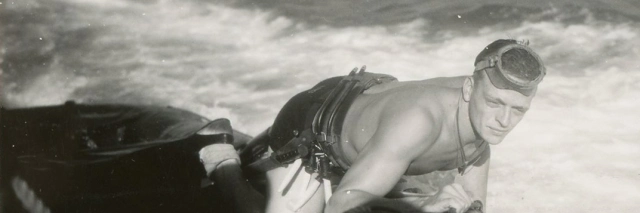

Baldwin was recorded on the census on April 10, 1940, living at the home of his mother-in-law, Mary A. Nowak (née Traynor, 1881–1961), 211 6th Avenue in Wilmington, along with his wife, daughter, and brother-in-law. He was described as a bellhop at a hotel. Later that year, when he registered for the draft, his employer was listed as the Hotel Du Pont. The registrar described him as standing five feet, 10 inches tall and weighing 150 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. A note attached to his draft card dated June 2, 1941, stated that he had moved to 2410 Jessup Street, his mother’s address. That probably indicates that he had separated from his wife, who resided at 211 6th Avenue during the war.

On January 28, 1942, Journal-Every Evening reported that Baldwin was one of 12 men selected by the Wilmington Fire Department who would start work on the morning of February 1, 1942. His address was listed as 2410 Chestnut Street, which is no longer extant. The paper later stated: “Baldwin was stationed at Engine House No. 6, Third and Union Streets. Before joining the fire department he was associated with the Hotel DuPont for five years.”

Curiously, Baldwin’s enlistment data card described him as a bellman rather than a fireman.

Military Career

After he was drafted, Baldwin was inducted into the U.S. Army in Camden, New Jersey, on January 23, 1943. Generally, men with dependent children born prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor were except from conscription until later in 1943. It is possible that Baldwin declined deferment. It is unclear whether a status of “separated, with dependents” rather than “married, with dependents” would have altered his draft status. According to a note that Baldwin’s mother sent to the Army, either Baldwin or his wife filed for divorce and was granted a degree nisi in June 1943.

Baldwin’s mother’s statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission indicates that he went on active duty at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on January 30, 1943. She wrote that he was assigned to the Chemical Warfare Service (C.W.S.) and stationed at Camp Sibert, Alabama—presumably where he attended basic training—before moving to Virginia.

The C.W.S. was created in 1918 due to the extensive use of poison gas in combat during World War I. The C.W.S. handled both defensive and offensive measures pertaining to chemical warfare, which was far more limited in World War II. Although the Allies did not use poison gas during the war, they did stockpile gas weapons to retaliate in the event their enemies employed chemical weapons first.

In June 1943, Private Baldwin joined his final unit, Company “C,” 81st Chemical Battalion, probably at Camp Pickett, Virginia, where the battalion was stationed from June 12, 1943, through October 14, 1943.

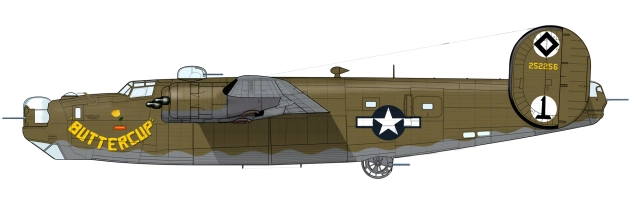

The 81st was one of the Army’s chemical mortar battalions, perhaps the most important C.W.S. contribution during World War II. Equipped with heavy 4.2-inch mortars, for all intents and purposes they served as infantrymen. Although their mortars were capable of firing mustard gas shells, in combat they were equipped only with high explosive and smoke/white phosphorus shells. A 1945 report, “The Combat Chemic,” described the weapon:

The 4.2-inch chemical mortar, or “goon gun,” looks like a stovepipe propped up by a jack. It packs a kick like a Missouri mule. The mortar consists of a baseplate, barrel and standard with a total weight less than 300 pounds.

It looks pretty tame until the gunner drops a beautifully tooled, 25-pound shell into the muzzle. With an ear-splitting bang, the missile sails out and disappears like a small pill in the sky. Seconds later the shell bursts with an enormous concussion, scattering fragments over an area 40 yards in diameter. Trained crews can get six shells in the air before the first one hits.

Since the grooves inside the barrel make the shell rotate like a bullet, the mortar is so accurate it can practically pick off a gnat on the wing. Sliding down the barrel, the shell ignites when it strikes a firing pin at the bottom. The propelling charge consists of flat powder rings strung doughnut fashion over a shotgun cartridge fixed at the base of the shell. As the propellant ignites, the exploding gases force a pressure disc on the shell to expand and engage the rifling on the way out of the barrel. Each shell holds about eight pounds of either smoke or TNT. Range is 4500 yards.

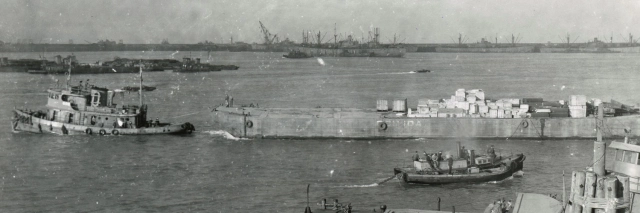

A 1945 book, The Eighty-First Chemical Mortar Battalion, described the battalion’s activities during the summer of 1943: “During the months of August and September, the battalion participated in several amphibious maneuvers with the 28th Division at Camp Bradford, Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia[.]” The book added:

In the course of training at the amphibious base the battalion received instruction and training in the use and adjustment of life belts, and in the purposes and characteristics of various types of landing craft. Naval customs and terminology, net scaling and adjustment of equipment, embarking and debarking from landing craft, loading and unloading of vehicles, and the installation and firing of the mortar in LCVPs were all studied. Later on the battalion, attached to the 28th Division, engaged in the practice assault on the “Solomon Islands” in Chesapeake Bay. For many members of the battalion this was the first experience with sea travel, and as a result a few cases of mal-de-mer were experienced. For its first ship-to-shore operation the battalion did an excellent job. This was also the battalion’s first experience with C and K rations, and we actually thought they were good.

Baldwin was promoted to private 1st class on October 1, 1943. The men of the 81st Chemical Battalion staged at Camp Shanks, New York, from October 15, 1943, until they boarded the British troopship Capetown Castle at the New York Port of Embarkation on October 20, 1943. They set sail the next day, arriving in Liverpool, England, on November 2, 1943.

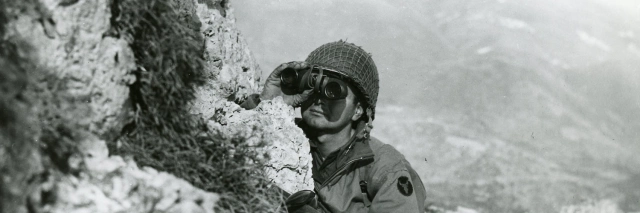

In late 1943, Baldwin was participating in a field exercise at the Hedgehog area of the Assault Training Center near Braunton, Devon, England. The training center was developed to prepare units for the amphibious warfare they would experience during the upcoming invasion of Normandy. For maximum realism, live ammunition was used in many of the training exercises, sometimes leading to casualties.

In an article about the Assault Training Center, Richard Bass described the Hedgehog area: “The culmination of every three week training course resulted in this area being assaulted by the trainees tackling twelve individual obstacles or fortifications which had to be overcome by the Infantry Assault Teams assisted by tanks, artillery and air attack.”

Around 1340 hours on December 15, 1943, a 4.2-inch shell exploded prematurely in the mortar tube. Private 1st Class Baldwin suffered fatal wounds to the right side of his body including his chest wall, abdomen, and thigh. He was declared dead on arrival at the 110th Station Hospital. Three other men from his company were killed in the accident: Private 1st Class William C. Frazier (1921–1943), Private Harold L. Kirby (1920–1943), and Private Louis W. Miller, Jr. (1924–1943).

Baldwin’s identification tags were not found, but his body was identified by his commanding officer. The four men killed in the accident were initially buried at a temporary American military cemetery at Brookwood, England, on December 21, 1943.

The 81st Chemical Battalion landed at Omaha Beach on D-Day in Normandy, June 6, 1944. Later redesignated the 81st Chemical Mortar Battalion, the unit fought in the European Theater until the surrender of Nazi Germany.

After the war, in 1947, Private 1st Class Baldwin’s mother requested that his body be repatriated to the United States. The following year, his casket returned to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the Lawrence Victory. His body was transported to Wilmington by train and turned over to the Hearn Funeral Home. After his funeral there on July 23, 1948, Baldwin was buried in Gracelawn Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware. His name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park nearby.

Notes

Birthdate

Most records give Baldwin’s date of birth as December 12, 1915, including his birth certificate and draft card. Since the birth certificate was filed soon after, it would appear authoritative, although it erroneously described him as his parents’ fourth child rather than their fifth. Curiously, his individual deceased personnel file listed his date of birth as December 12, 1916. Baldwin served in the U.S. Army as Roy A. Baldwin, with no suffix.

Father’s Death

Baldwin’s father’s death certificate described his death as due to lobar pneumonia, while a newspaper article attributed it to influenza. Many victims of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1920 were first sickened by the flu and then succumbed to secondary infections which led to pneumonia.

Marital Status and Wife

Baldwin may have met his wife at work, since her obituary stated that she “had worked as an elevator operator for over 10 years at the Hotel du Pont in Wilmington.”

According to U.S. Army records, Baldwin was separated when he was inducted and divorced at the time of his death. Interestingly, Catherine Baldwin submitted an affidavit to the Army laying claim to Private 1st Class Baldwin’s personal effects in which she acknowledged the couple were separated but denied that they had divorced. A note by his mother to the Army when filling out the form requesting the repatriation of his body clarifies the discrepancy:

My son had been separated from his wife for about three years prior to his death. A divorce was pending and the Decree Nisi was granted in June 1943, six months prior to my son’s death. In Delaware, a divorce does not become final until one year after the Decree Nisi.

After the war, Catherine Baldwin remarried, to Frederick Lester Harter (1920–1975), himself an Army World War II veteran.

Daughter

Baldwin’s daughter, Janice E. McKnight, was found murdered in her home on October 13, 2000. The case was still unsolved as of January 24, 2022, when it was included in a list of New Castle County cold cases printed in The News Journal.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for obtaining payroll records and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

Alexander, Susan. Individual Military Service Record for Roy A. Baldwin. August 24, 1949. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17602/rec/2

Application for Headstone or Marker for Frederick L. Harter. December 1, 1975. Applications for Headstones and Markers, July 1, 1970 – September 30, 1985. Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/2375_02_01053-03299

Application for Headstone or Marker for William C. Frazier. August 5, 1948. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_2421401757_0020-01481

Bass, Richard. “The WW2 US Assault Training Center in Devon.” The American, May 30, 2019. https://theamerican.co.uk/pr/ft-US-Assault-Training-Center-Devon

“Catherine A. Harter.” The News Journal, November 6, 1990. https://www.newspapers.com/article/138636498/

Certificate of Birth for John Baldwin. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-62VW-PWQ

Certificate of Birth for Roy A. Baldwin Jr. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS76-D91N-D

Certificate of Death for John Baldwin. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9BB-Q92V-M

Certificate of Death for Roy A. Baldwin. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-D51Q-B6J

Certificate of Marriage for Roy Alonzo Baldwin and Catherine Agnes Nowak. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6YJS-5V2

“The Combat Chemic.” Office of the Chief, Chemical Warfare Service. March 8, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Draft Registration Card for Roy A. Baldwin. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_10_00001-00991

The Eighty-First Chemical Mortar Battalion. Unknown publisher, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“First Presbyterian Church (Wilmington, Delaware) Baptisms 1909 – 1919 Births 1898 – 1918.” Presbyterian Church Records, 1701-1907. Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61048/images/44861_620303987_0434-00057

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9R6W-H99

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Roy A. Baldwin. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

James, Thomas H. “Organizational History.” June 1, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Louis W Miller Jr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86180469/louis-w-miller

“Pay Roll of Company ‘C’, 81st Chemical Battalion. APO 652 4.2 In. Cml. Mortar For month of October 1943.” October 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

“Pay Roll of Company ‘C’, 81st Chemical Battalion. Camp Pickett, Virginia 4.2 In. Cml. Mortar For month of June 1943.” June 30, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

“Pfc. Roy A. Baldwin.” Journal-Every Evening, July 21, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/article/138661697/

“Roy Alonzo Baldwin Sr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/237264026/roy-alonzo-baldwin

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-9N7

“Soldier Dies In England.” Journal-Every Evening, December 22, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/138635520/

“These Workers Loyal to Loan.” The Evening Journal, October 25, 1918. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-evening-journal-roy-baldwin-death/138473947/

Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C.

“Twelve New Firemen Will Start Duty Feb. 1.” Journal-Every Evening, January 28, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/138663108/

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/display-partial-records.jsp?f=3475&mtch=1&q=32488624&cat=all&dt=893&tf=F

Last updated on June 6, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.