| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Sheet metal worker at Bellanca Aircraft |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army Air Forces | 13124018 |

| Theater | Unit |

| American (Zone of Interior) | Squadron “E,” 422nd Army Air Force Base Unit |

Author’s note: This article contains intense details about a serviceman’s suicide that may be upsetting to some readers. Suicide was and remains a serious problem in the armed forces but I felt in this case to fully withhold details would be to leave his story incomplete.

Early Life & Family

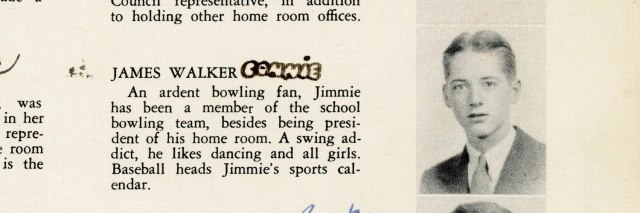

Charles Edelberg was born at 127 West 11th Street in Wilmington, Delaware, early on the morning of April 2, 1920. He was the son of Barel Edelberg (also known as Berl or Benjamin, a grocer, c. 1885–1930) and Katie Edelberg (née Levine, c. 1891–1980). His parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia. Both had settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and both lost their first spouses to illnesses. Edelberg had at least five older half-siblings from his parents’ first marriages (of whom two died before his birth) and a younger brother.

Edelberg’s family moved to Wilmington shortly before he was born. On May 11, 1925, Edelberg’s parents purchased a property at 101 North Clayton Street in Wilmington, his home until he entered the service. The Evening Journal reported Edelberg’s sixth birthday, noting that his “favorite pal is his dog, ‘Bud,’ with whom he is seen all day long.”

The Edelberg family ran a grocery store located in the same building as their home. On September 22, 1930, when Edelberg was 10, his father was severely injured in a car accident and died in a hospital in Rahway, New Jersey. His mother took over the family business.

In 1936, Edelberg won the Norman I. Harris trophy for the highest point score at the annual water carnival held by the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association of Wilmington.

Edelberg was described as a grocery store clerk, presumably at the family store, on a census record taken April 4, 1940. When Edelberg registered for the draft on July 1, 1941, his occupation was similarly recorded as grocer. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, nine inches tall and weighing 140 lbs., with black hair and brown eyes. He later worked as a sheet metal worker at the Bellanca Aircraft Corporation factory before entering the service.

Edelberg was attending the Thomas F. Bayard School as of May 27, 1933. Both the 1940 census and Edelberg’s enlistment data card described him as a high school graduate.

Military Career

Edelberg volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Forces in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on September 30, 1942. By the following day, he was stationed at the U.S. Army Reception Center, New Cumberland, Pennsylvania.

In a statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission, Edelberg’s mother provided a detailed summary of his movements, but not dates:

- Camp Luna, New Mexico

- Morrison Field, Florida

- Chanute Field, Illinois

- McChord Field, Washington

- Hammer Field, California

- Chanute Field, Illinois

- Tonopah Army Air Field, Nevada

(Curiously, an October 16, 1943, letter and an October 21, 1943, newspaper article indicates that Edelberg transferred directly from McChord back to Chanute, with no mention of Hammer Field. There is also circumstantial evidence that Edelberg briefly returned to McChord Field between his last stint at Chanute Field and his move to Tonopah.)

Letters that Edelberg wrote to Mollye Sklut (1906–2006), now in the archives of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware, provide insight into his military career. Sklut, a Wilmington woman, maintained correspondence with hundreds of Delaware’s Jewish servicemembers all over the world. She often sent them copies of The Y Recorder, the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association of Wilmington newsletter, which included a column with their letters to her, entitled “Dear Mollye.”

As of November 18, 1942, Private Edelberg was with the 24th Ferrying Squadron at Morrison Field, Florida, now Palm Beach International Airport. He wrote to Sklut:

The weather here is tops, I’ve always wanted to spend the winter in florida [sic], but I never expected to get there this way. […]

By the way, I heard an old Wilmingtonian orchestra in camp yesterday. Richard Himber and his Band put on a show in the camp theatre. It sort of made me feel good to see and hear that someone from Wilmington, could draw any attention in this camp.

If I keep up this way you’ll think that I’m so satisfied that I don’t care if I never go back to Wilm, but don’t get me wrong, there is no place I’d rather be anytime.

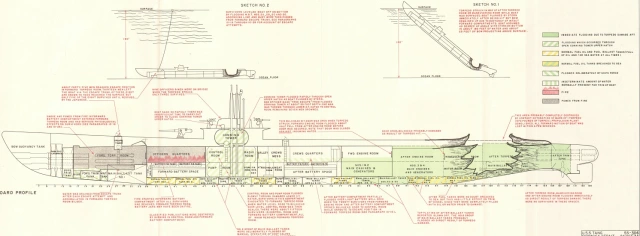

Private Edelberg left Morrison Field on January 2, 1943, arriving the following day at Chanute Field, Illinois. Edelberg was assigned to the 7th Technical School Squadron while attending a course to become a Link Trainer instructor. An early form of flight simulator, Link Trainers proved vital in the massive expansion of air forces in American and Allied nations. The devices were equipped with simulated instruments and moved using sets of bellows as the pilot manipulated the controls (or to simulate various flight conditions set up by the instructor). In a letter dated January 5, 1943, Edelberg wrote that he was disappointed to find himself in Illinois during the winter given that “The season was just opening down South and I was really having the time of my life[.]”

Private Edelberg wrote on February 15, 1943, that he was “Still going to school, in fact I won’t be finished till late spring[.]” By the time of his next extant letter, dated October 16, 1943, Edelberg had been promoted to corporal and was with the 8th Technical School Squadron. He had recently returned to Chanute Field from McChord Field, Washington, about one month earlier. He grumbled:

So help me I’m finally getting tired of moving around this country. I’d like to stay in one place 4 mo. just to break a record. I don’t even get a kick out of riding cross country on a train, chances are 99 of 100 that I’ve been thru there before.

He added: “About the only excitement I get out of the Army is routine & train rides which isn’t much from my point of view.”

On October 28, 1943, Edelberg wrote that the day before, he had been reduced back to private 1st class for inscrutable reasons:

I don’t understand it but then neither does anyone else here. The first I had heard was that I was redlined on the payroll as there was a change in my status.

I went to Headquarters to find the reason, and they showed me an order from McChord Field remaking me a P.F.C. It could be a case of mistaken Identity—I hope! But then I’ll find out soon enough. I finish school here Nov 15th. And should be back at McChord Field shortly after.

Edelberg briefly returned to McChord Field, but he wrote in a letter printed in The Y Recorder on December 31, 1943: “It seems that they don’t have and won’t have the new type of equipment that I went to school to learn about, so I’ll go some place where they do.”

Soon after, Private 1st Class Edelberg was ordered to Tonopah Army Air Field, Nevada. In a letter to Sklut, Edelberg described his journey:

I left McChord by myself so naturally I took my time getting here. Spent 12 hrs. in Portland, and 24 in Reno. Reno! Wow! What a town. Take the heart of New York and only the best of that, Set it out in the middle of the dessert [sic] & that is Reno. I had more fun in 24 hrs than I’ve had since my furlough last Summer.

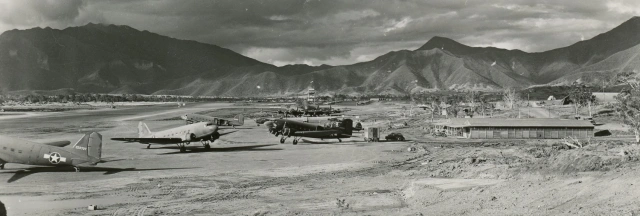

Edelberg’s transfer coincided with a major expansion of that base’s training facilities. A November 1943 Tonopah Army Air Field history stated:

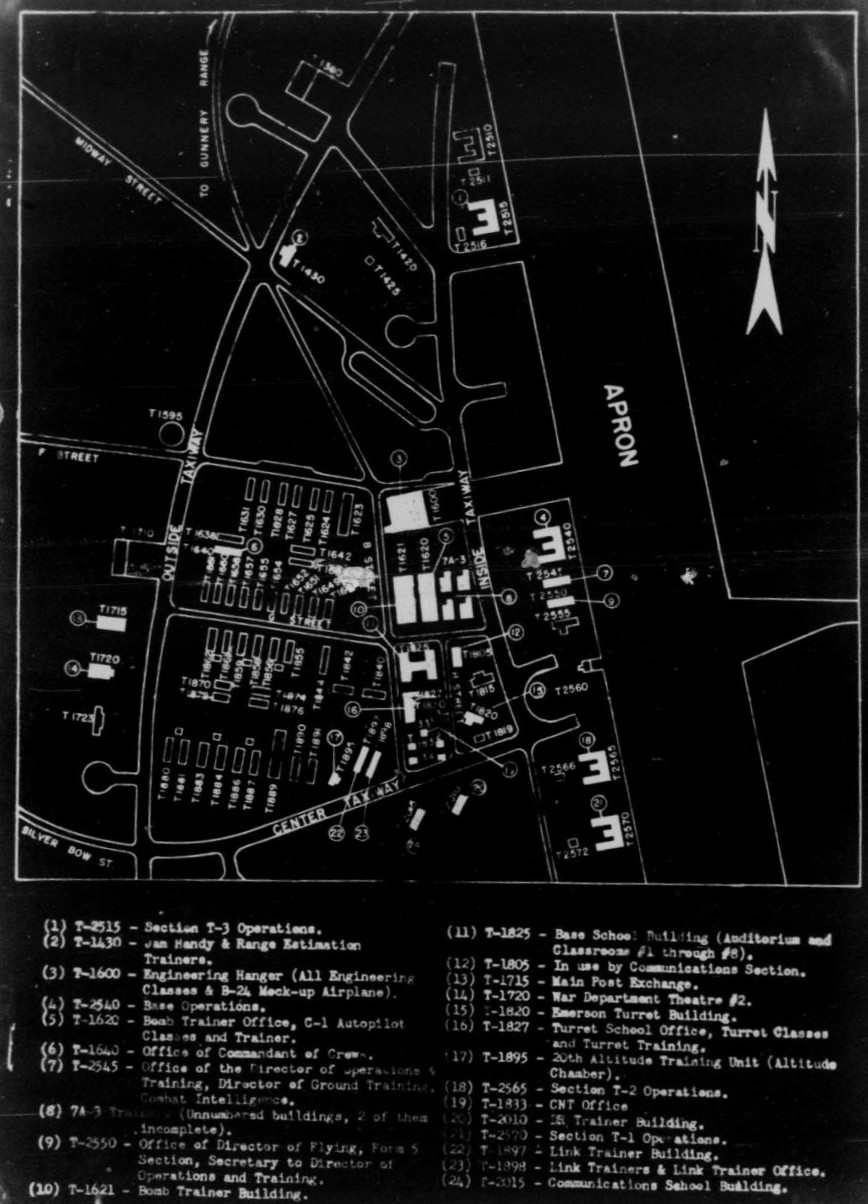

Numerous training devices have been installed or are being installed which will increase training efficiency. Two celestial navigation trainers are under construction. Four link trainers are in operation and six more will be in operation shortly. One out of three Bomb trainers is in operation.

Around January 5, 1944, Private 1st Class Edelberg joined the 413th Air Base Squadron, U.S. Fourth Air Force, at Tonopah. The unit had been activated mere days earlier, on January 1, 1944, when several units station at Tonopah were consolidated as detachments of the 413th Base Headquarters and Air Base Squadron.

In a letter to Sklut dated January 9, 1944, Edelberg wrote:

Guess what? Another change of address. From one extreme to another. McChord was in the land of trees; big trees, little trees, and plenty of trees. Down here there isn’t a tree within miles. Just a desert,–sand and sagebrush. […]

Our equipment is just beginning to get here and although today is my first day here, I’ve really put in a good day’s work today.

Edelberg’s first impressions of his new base were favorable. He praised the food and added that Tonopah Army Air Field was so big, “There’s a story around about a boy that went Awol [absent without leave] for 4 days, but they couldn’t court-[martial] him because even though he walked steadily in one direction, he had never left the field.” On the other hand, he wrote, the nearby town of Tonopah “is small, nothing there but Gambling houses & saloons.”

Staff Sergeant Harry Swinkin (1919–2008), who served with Edelberg in the Celestial Navigation Training Department, later recalled in a July 31, 1945, statement:

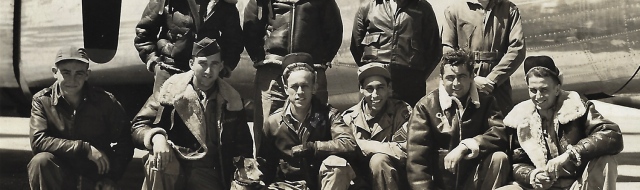

I first met Sergeant Edelberg […] when he first came to Tonopah Air Field and we opened the C.N.T. Department. During the months that I knew him, he appeared perfectly normal and sane and not unduly worried about anything, although in the past two months he seemed to have quieted down somewhat. He was a good worker, one of the best we had there and received his promotions regularly. He occasionally went with me to the N.C.O. [noncommissioned officer] Club, where we “cut up” a bit, but as a rule, did not go out very much, but stayed close to the barracks.

By February 19, 1944, when he next wrote to Sklut, Edelberg had been promoted back to corporal and was a member of Detachment “A,” 412th Air Base Squadron. He wrote:

Everything here is just about the same—“FUBAR”—Don’t try to decipher that expression, it means the same as all the other abbreviations. […]

The other day even the weather went screwy; We had Snow, Hail, & rain. All simultaneously, and the sun shone all the time. […]

But never the less everyone here is fairly happy. We have a good Gym we can wear ourselves out in nightly, and this altitude really makes your lungs really burn at first. Then there is the Movie, and when you reach the breaking point you can always go into town; get drunk and blow your top.

As of March 13, 1944, Corporal Edelberg was assigned to instrument flying trainers with the 470th Bombardment Group (Heavy), a replacement training unit, “and moved to the far end of the field. It now requires a 3 day pass just to get to the main gate.”

Corporal Edelberg’s next extant letter, dated April 13, 1944, suggested he was under strain. He told her he had been arguing with his comrades about small things, such as who was going to turn off the light in their barracks. He added:

But then Mollye I’m not really nuts — every body else in this cockeyed world is. That’s what the fellows tell me.

Mollye do you know that I’m eligible for a furlough and can’t get it. Our Major keeps finagling my papers from reaching Headquarters. We haven’t got our equipment completely installed and won’t for a while — so that kills it. I haven’t even been able to get a pass since I’ve been here — Since Jan. 5th. Pardon — nite passes yes but not a day off. However I did finagle a 3 day pass for April 20th. — Reno Look Out!

Although the original may no longer exist, excerpts of another letter from Edelberg to Sklut was published in the Y Recorder on March 8, 1945. Edelberg, now a sergeant, wrote that “another fellow and myself bought an old Model A Ford Roadster and drove it on a three-day pass to Los Angeles, California. During the journey, they were driving through the Mojave Desert when “we ran into a cloudburst. […] The roof leaked, the curtains would not keep out the water; we had to open one of the doors to let the water out of the car.”

In the same letter, Edelberg wrote facetiously that, inspired by the example of two other men who received medical discharges,

I’m going to start making faces at all the Medics and see if they won’t put me in the “nut ward” for a few days. I think I could convince them that I am a damned good prospect for a section 8 [mentally unfit discharge]. All I’d have to say to them is “Tonopah doesn’t bother me, bother me, bother me. I like it here, I like it here.” That should do it.

By mid-1945, Edelberg was a member of Squadron “E,” 422nd Army Air Force Base Unit. The 422nd A.A.F.B.U. had been activated on April 1, 1944, following another reorganization which saw the deactivation of several units including the 470th Bomb Group as well as the 413th Base Headquarters and Air Base Squadron.

A summary of Sergeant Edelberg’s service record dated July 30, 1945, stated that “Efficiency rating of EM [enlisted man] was excellent.” It also noted “he was recommended for the Good Conduct Medal while stationed at McChord Field, Washington.”

Staff Sergeant Swinkin stated:

Sergeant Edelberg never mentioned any particular difficulty. His home life was apparently normal and he never made any complaints of any nature to me. His record militarily was good. I don’t know of any courts martial which he may have suffered nor was he a particularly heavy drinker. On occasion I have seen him take a couple of beers at the NCO Club, but I have never seen him drunk.

Mystery in Oakland

On July 2, 1945, Sergeant Edelberg began a furlough. The war in Europe was already over and V-J Day was just two months away. His commanding officer, Captain Robert H. Fowler, authorized him to proceed home to Wilmington and then return to Tonopah by midnight on the night of July 27–28. At the end of his visit, Edelberg left Wilmington on Monday, July 23, 1945. He told his family that he would be taking a train to Ogden, Utah, and travel by bus the rest of the way to Tonopah. They recalled later that he seemed to be in good spirits.

Although Sergeant Edelberg had no known history of mental illness, evidence subsequently came to light that when he left home for the last time, Edelberg was either having—or would soon suffer—a major mental health crisis. He did not return to Tonopah, instead continuing west to Oakland, California.

A civilian, Helen Silvius, later testified that at 0800 hours on the morning of July 27, 1945—16 hours before Edelberg’s furlough would expire—he was waiting when she opened the Alameda County Travelers’ Aid Society booth at the 16th Street Station in Oakland. He told her that he had arrived by train that morning and was supposed to meet a colonel there. Oddly enough, he stated that he did not know the officer’s name, but that he was supposed to go with this colonel to March Field. The base was well to the south of Oakland, closer to Los Angeles. In fact, his commanding officer had not issued—and was not aware of—any orders changing Edelberg’s duty station.

After a few hours, Edelberg asked about the possibility of calling March Field. She suggested he call them from the local Red Cross at 10th and Fallon Streets, about 2½ miles to the southeast. Although Edelberg left around 1030 hours, he returned at 1130 “and stated that he was unable to find the address.” Although she provided him with a set of directions, he sat down to read a newspaper until he left at noon.

Silvius did not suspect anything was amiss, stating:

During the few hours that he spent in the waiting room and during the time he conversed with me, he did not seem unduly apprehensive or worried. He merely appeared confused about the change of orders and the colonel. He spoke very well and had a very pleasant manner, being entirely cooperative at all times.

A local coin-operated phonograph business owner, Melvin Baer (1902–1955?), owner of a 1939 Plymouth Coupe, Deluxe, later testified:

I had parked my car at Second Avenue and E. 14th Street for the purpose of purchasing some book matches in a drug store on that corner. I purchased two dozen boxes of book matches, each box containing approximately 50 books. I came out of the drug store and placed the matches in the front seat of my Plymouth coupe. I then returned to the store to pay for the book matches. At this point I only spent about 40 to 50 seconds in the drug store, just to make the payment, and when I returned to the car I found it was gone. I had left the keys in the ignition.

The vehicle theft occurred about three miles southeast of the train station—and half a mile east of the Red Cross—at around 1300 hours. The car was next spotted around 1420 hours another seven miles southeast, on 98th Avenue near Castlewood Street or Mountain Boulevard, depending on the source. The vehicle was occupied by Sergeant Edelberg, who had spilled matches on the floor to a depth of three inches.

A passerby, John Kennedy, 39, later testified that “I was going East on 98th Avenue when I saw smoke coming from the open windows of this auto.” He discovered a man laying across the seat, striking matches, “of which there appeared to be hundreds on the floor, on fire.”

Kennedy testified that he “patted him on the back and said, ‘Come on fella, get out of there.’” The man refused to be rescued. Kennedy flagged down a passing bus. According to Kennedy, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Stanley A. Warhanik (1912–1997) and another passenger, Milo Arnett (1903–1967) joined Kennedy in attempting to rescue Edelberg, but he continued to resist their efforts. In Kennedy’s telling, Lieutenant Warhanik pulled on Edelberg’s leg but came away with only his shoe. Curiously, Lieutenant Warhanik stated that the “the flames made it difficult to approach the car. For this reason neither I nor the bus driver attempted to get him out.” The Army also concluded that, contrary to Kennedy’s account, Arnett had been at the scene afterward but not involved in a rescue attempt.

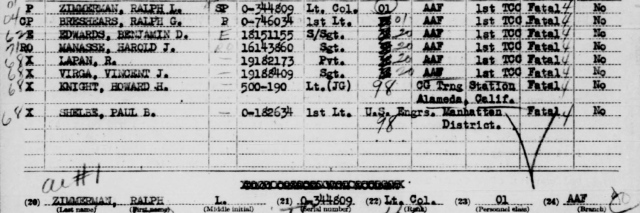

The bus driver sprayed a fire extinguisher on the fire, to no avail. By the time the fire department arrived, Edelberg had died of severe burns. Lieutenant Warhanik found a note written on a matchbox cover. Police recovered several items at the scene including his wallet, identity papers, and the directions from the station to the Red Cross. Silvius, the rescuers, and Staff Sergeant Swinkin identified Edelberg as the man in a photograph recovered from the wallet. Laundry marks on what remained of Edelberg’s clothing also confirmed his identity.

During World War II, it was usually days or weeks before the families of fallen servicemembers learned that their loved ones were missing or dead. Though news of stateside deaths were often relayed more quickly, Edelberg’s family learned of his death with unusual speed outside normal channels. Detailed accounts of his death distributed by the Associated Press and United Press were printed in newspapers nationwide during the two days following his death. Cruelly, the Associated Press version of the story, which was generally accurate but described Edelberg as a Marine, was printed in the Wilmington Morning News on July 28, 1945, mere hours after his death.

Edelberg’s family desperately sought answers through the Delaware Chapter of the American Red Cross, but it wasn’t until July 30, 1945, three days after Edelberg died, that the Army officially confirmed his death to Edelberg’s mother. The Wilmington Morning News stated that the Army told the Red Cross that “the soldier’s name was published, contrary to military practice, before Army authorities knew of his death.”

1st Lieutenant Bernard E. Patty, Jr. (probably 1912–1993), a Medical Administrative Corps officer at Oakland Army Service Forces Regional Station Hospital, investigated to determine the line of duty status of Sergeant Edelberg’s death. He wrote that testimony “indicates that Sgt Edelberg was a man of no bad habits and an excellent soldier.” Witnesses testified that they saw no evidence of intoxication. Patty wrote that “Despite no previous history of mental unsoundness on the part of Sgt Edelberg, his course of conduct on that day leads to an inescapable conclusion that he was mentally irresponsible at the time of his death.”

Therefore, Lieutenant Patty concluded, “his death should be regarded in line of duty since there is no evidence that his mental irresponsibility was a result of his own misconduct.”

The Army apparently told Sergeant Edelberg’s family very little about his death other than that it was in the line of duty, leaving them bewildered about the strange circumstances of his death reported in the newspaper.

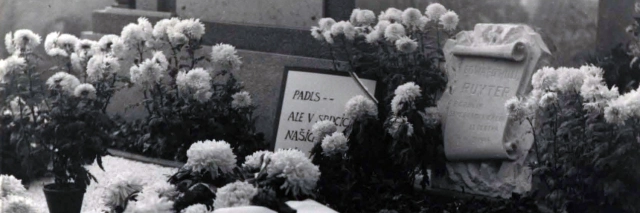

Staff Sergeant Swinkin escorted Sergeant Edelberg’s casket home to Wilmington. Rabbi Henry Tavel (1905–1969) of Wilmington’s Congregation Beth Emeth, a U.S. Army chaplain, officiated during services at the Chandler Funeral Home on August 5, 1945. Sergeant Edelberg was buried in the Jewish section of Lombardy Cemetery, now known as the Jewish Community Cemetery, where his father had been buried. His mother and one of his half-sisters were also buried there after their deaths.

Sergeant Edelberg is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle and on a memorial at the Jewish Community Cemetery for fallen local Jewish servicemembers.

Notes

Year of Birth

Discrepancies in year of birth are surprisingly common among World War II servicemen. Edelberg’s headstone lists his date of birth as April 2, 1919. However, his birth certificate, draft card, and multiple documents in his reconstructed personnel file all establish that his date of birth was April 2, 1920. Similarly, an April 3, 1926, item in The Evening Journal announced that he had just celebrated his 6th birthday.

Personnel File

Like most members of the U.S. Army during World War II, Sergeant Edelberg’s original personnel file was destroyed in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire. However, Lieutenant Patty’s investigation file was either off-site or was in a part of the building not damaged by the fire and later became part of Edelberg’s reconstructed file, known as an R-file, preserved at the National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Sergeant Edelberg’s nephew, Barry Edelberg, and to Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photos. Thanks also go out to Craig Feinstein, grandson of Edelberg’s half-brother, for photos and information. Finally, let me express my appreciation to the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware for the use of Edelberg’s letters.

Bibliography

“Administrators Are Named of Three Estates.” The Daily Home News, November 7, 1930. https://www.newspapers.com/article/133922466/

“Army Confirms Death of Charles Edelberg.” Wilmington Morning News, July 31, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/133868925/

Certificate of Birth for Charles Edelberg. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6967-9FK

“Dear Mollye.” The Y Recorder, December 31, 1943. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/d9e6749fbd0d6c2c6dfc0e397de39341.pdf

“Dear Mollye.” The Y Recorder, March 8, 1945. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/c69c24c7942a4e6d2277ebb4cbae6fc5.pdf

“Death Ends Holiday for Auto Tourist.” The Evening Journal, September 23, 1930. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-evening-journal-benjamin-edelberg-fa/133922637/

Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_256996-00101

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, April 13, 1944. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/1be386b20f8006302c844e1b8aed8072.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, December 15, 1942. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/2a1a27bc641cb24c7f7f4bbc80c05e22.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, February 15, 1943. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/fed553101027d18de5832bfbc5acdf90.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, February 19, 1944. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/e85c379405effa34d6559f596c08f6b7.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, January 5, 1942. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/ddb2edc237f28f9a152c4f55d684404d.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, January 9, 1944. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/80d687f4749da513690231409a1005ba.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, March 13, 1944. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/7fa1da54a5fb3a2edccadcb182ec9bea.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, November 18, 1942. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/4762e3b4c5ecfe258628fae9435a2532.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, October 16, 1943. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/aa2ac46d1f4c67c15745be9bf90f5ba6.pdf

Edelberg, Charles. Letter to Mollye Sklut, October 28, 1943. Dear Mollye Letters. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/files/original/55cbf098643078bf1e9d1ddbb08de66c.pdf

Edelberg, Katie. Individual Military Service Record for Charles Edelberg. Undated, c. 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18615/rec/1

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531894_00906

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4385039_00244

“Funeral for Sergeant.” Journal-Every Evening, August 2, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article//89030608/

“Funeral Services Held for Sergt. Edelberg.” Wilmington Morning News, August 6, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/134101173/

“Happy at 6.” The Evening Journal, April 3, 1926. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-evening-journal-charles-edelberg-6/133869155/

“Harry Swinkin.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/232711528/harry-swinkin

“History of Tonopah Army Air Field, Tonopah, Nevada, 1 January 1944 – 31 January 1944” Undated, c. February 1944. Reel B2616. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Mueller, George E. “Monthly Historical Report, Tonopah Army Air Field, Tonopah, Nevada, November 1943.” Undated, c. December 1943. Reel B2616. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Official Military Personnel File for Charles Edelberg. Official Military Personnel Files, 1912–1998. Record Group 319, Records of the Army Staff. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Our Men and Women In Service.” Journal-Every Evening, October 21, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/89030692/

Petition for Naturalization for Harry (Harshall) Swinkin. Petitions for Naturalization, 1890– 1991. Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685–2009. National Archives at Seattle, Washington. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2531/images/31886_1421012669_0071-00420

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00552-00777

“Sobbing Mother Doubts Word Of Soldier Son’s Suicide.” Journal-Every Evening, July 28, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/89030640/

Thompson, Edith O. “History of the Tonopah Army Air Field, Tonopah, Nevada, 1 June 1944 thru 30 June 1944.” Undated, c. August 5, 1944. Reel B2617. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Wilmington Marine Burns Self to Death.” Wilmington Morning News, July 28, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/89030562/

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=13124018&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=761500

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, 10/16/1940–3/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_08_00002-00794

Last updated on January 28, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.

Thank for doing this research. Charles Edelberg was my great uncle whom I never met.

LikeLiked by 1 person