| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Georgia, Florida | Construction/maintenance painter |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 34051507 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion |

| Military Occupational Specialty (Presumed) | Campaigns/Battles |

| 610 (gunner, antitank) | Tunisian campaign, Italy (including Cassino and Anzio) |

Author’s note: Delaware’s World War II Fallen occasionally highlights men and women without any known connection to the First State. This article, part of a series about the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion, incorporates some text from my articles “Sergeant Robert D. Lightsey (1911–1944)” (published on this site), “1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie: Jack in the Alice Griffin Letters” (published at the 32nd Station Hospital website), “Captain William W. Galt: ‘Always Out In Front’” (published on the Congressional Medal of Honor Society website), and “Baker D. Newton” (published at TankDestroyer.net).

Early Life & Family

Elmer Franklin Park was born in Hooker, Georgia, on June 21, 1919. He was the son of Walter Elmer Park (1893–1981) and Bernice White Park (1896–1996). He had an older brother, Horace Cooper Park (1916–1997). He also had two younger brothers, William “Bill” Porter Park (1921–2012) and Thomas “Tommy” Melvin Park (b. 1925), and a younger sister, Betty Imagene Park (b. 1929). As of June 5, 1917, Walter Park had been working as a civilian carpenter at Fort Oglethorpe, Florida, although at that time, the Park family had been living in another nearby town, Ringgold.

Soon after Elmer Park’s birth, his family began a journey to Washington state, where his father had been born. Park’s nephew, John R. Park, explained:

Part of Walter’s motivation may have been to visit his aunt Eva (Meek) Aust, and possibly other Meek relatives. So, about 1920, Walter and Bernice, with their young sons Horace and Elmer, drove to the Seattle area. The trip took several months each way, camping along the way, with Walter working odd jobs for a week or more at a time for gas and food money.

The family was still in Washington as of November 25, 1921, when Park’s younger brother, William P. Park, was born in Enumclaw. John R. Park added that “They probably returned to the Chattanooga, TN area about 1922. The family home was on Missionary Ridge, GA (now a suburb of Chattanooga, TN).”

However, by November 17, 1925, when Thomas M. Park was born, the family had relocated to the area of Hialeah, Florida. Park’s nephew explained that the family moved “to the Miami area in 1925, initially living on the west side of Okeechobee Canal (paralleling US27, aka West Okeechobee Road) in what is now Medley, FL or Hialeah Gardens, FL.”

The Park family was recorded on the census on April 21, 1930, living on a farm in Precinct 7 in unincorporated Dade County outside Hialeah. Park’s father was working as a farmer. The family was recorded on the 1935 Florida census living on South Canal Road in Precinct No. 49 in Dade County. The family was recorded during the next national census on May 9, 1940. They were listed as living at a farm located at 6620 N.W. F.E.C. (Florida East Coast) Canal Road in Dade County. John R. Park noted:

By about 1933, the Park family had moved into Miami Springs. The mailing/legal address was 6620 NW F.E.C. Canal Road (now North Royal Poinciana Blvd), which was probably the address for the entire property (most of the north half of Miami Springs), which was not subdivided at the time. The Park family were share-croppers (renters), and there were at least several other families with homes on the larger property. Today, the address of the Park house at that time would be “901 Dove Avenue” (but the old frame house no longer exists).

At the time of the 1940 census, Park was listed as a laborer in the construction industry but had been unemployed for the past six months. The rest of the family (except the youngest, Betty) were working. Park’s father was still farming, while his mother was working as a school cafeteria cook. His older brother was a mechanic, while his younger brothers were working as a newsboy and caddie, respectively.

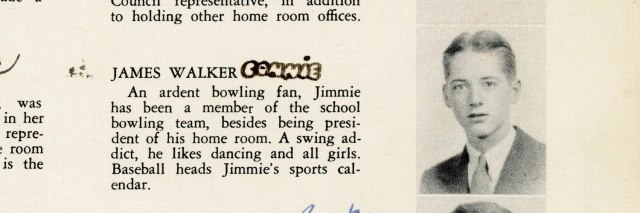

According to the 1940 census and his enlistment data card, Park completed three years of high school. When he registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, Park was living with his family on South Canal Drive in Miami Springs, Florida, and working for R.I. Dickerson Painting & Decorating Co. at the corner of 3rd Street and 2nd Avenue, N.W., Miami. The registrar described him as standing six feet, two inches tall and weighing 158 lbs., with blond hair and blue eyes. Park’s enlistment data card recorded his civilian occupation as construction/maintenance painter.

All three of Park’s brothers also served in World War II. Horace served in the U.S. Navy, while Bill and Thomas served in the U.S. Army.

Stateside Service & England

Park was drafted before the U.S. entered World War II. He joined the U.S. Army at Camp Blanding, Florida, on April 11, 1941. By the fall of 1941, Private Park was a member of the 94th Antitank Battalion at Fort Benning, Georgia. At the time, the unit was equipped with towed 37 mm antitank guns.

Park wrote a letter about his experiences during maneuvers in Louisiana that was printed in The Miami Herald. Although not published until October 5, 1941, the information Private Park provided places it as Phase 2 of the maneuvers, which officially began on Wednesday, September 24, 1941.

The Third Army (Blue) which I am in, is fighting the Second Army (Red). We have the most men, but the Second has two armored divisions. […] We started off bright and early Monday by getting up at 3 a. m. We went into position seven times and drive more than 160 miles before night. […] Tuesday afternoon. We didn’t do very much today, just moved two times, but had to dig our gun in position. I was supposed to dig a fox hole, but didn’t.

Park continued his narrative by describing the meals:

Wednesday morning. We had supper last night at 10:30 o’clock, consisting of beef stew, cabbage (raw), mashed potatoes, butter, pineapple (one slice), and bread (it was molded). This morning we breakfasted at 2:45 a. m., and had one hard boiled egg, one spoon of grits, and two slices of bread. Oh yeah, coffee without cream or sugar. If it don’t get better, I don’t know what we are going to do.

We were expecting a tank attack this morning, but so far everything is quiet. We are still in the same position as last night. Yeah, I just thought of something. Last night I made a hammock by tying the ends of a blanket to two trees. The only two trees that were close enough were across a branch or creek. I came back from supper and got in. You guess it, it broke and I got wet.

Park concluded his letter noting that

We stayed in the same position all day Friday and didn’t even see one tank. We didn’t get to fire a shot so far, but one boy was playing with a blank and it went off and hurt him pretty badly. He was sent to the hospital.

The letter is remarkable, especially in comparison with those from other soldiers that would come out of the warzone in subsequent years. Due to censorship regulations, it would not have been possible for him to write nearly so detailed—or blunt—a letter once the U.S. entered the war and he went overseas. Tongue-in-cheek though it may have been, Park would surely encounter far worse food during his subsequent career in the U.S. Army. If nothing else, it is also safe to say that his indifference towards foxholes must have changed—if not during training, then once he entered combat in early 1943!

Later that fall, around December 15, 1941, the 94th Anti-Tank Battalion was redesignated as the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. By December 25, 1941, Private Park was a member of Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. In March 1942, the battalion moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

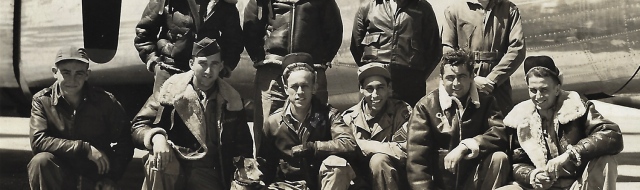

By July 3, 1942—when he appeared in a company photograph at Fort Bragg—Park had been promoted to technician 5th grade. It is unclear what his duty was. Based on a change of duty roster dated September 4, 1943, many of Company “C” tech 5s were vehicle drivers, though a few had other duties such as armorer, mechanic, rifleman, or gunner. Unfortunately, Park was not among the men whose duties were documented in available records.

Before going overseas in the summer of 1942, the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion reequipped with the M3 Gun Motor Carriage, a halftrack equipped with a 75 mm gun. Technician 5th Grade Park and the rest of his unit shipped out from the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the British transport Andes on August 6, 1942, arriving in Liverpool, England, on August 17, 1942. On the night of January 5, 1943, Company “C” boarded a train at Chiseldon Camp, arriving back in Liverpool at 1115 hours the following day.

Combat in Tunisia & Italy

The 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion sailed for North Africa on January 8, 1943. Their ship arrived in Oran, Algeria—or nearby Mers-el-Kébir—on January 16 or 17, 1943. Allied forces had taken Morocco and Algeria from the Axis-aligned Vichy French forces during Operation Torch, beginning on November 8, 1942. On February 14, 1943, Park’s unit headed east to join the Tunisian campaign.

In a letter to his family, 1st Lieutenant (later Major) Baker D. Newton (1918–1961), then the Company “C” executive officer (and later Park’s company commander), recalled the unit’s baptism by fire during the Battle of Kasserine Pass on February 20, 1943. A few miles from the front, Company “C” was leading the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion when they began encountering demoralized American infantry heading the other way. Soon after, three enemy armored cars approached.

Then all hell broke loose from our guns – – all firing too hastily. We hit one of them, the others escaped back into the pass. By this time we were taking somewhat of a shellacking from artillery and machine guns which had moved along the sides of the valley on our flank.

About a month later, the 894th Tank Destroyer participated in the Battle of El Guettar. The battalion led Allied forces into Bizerte on May 7, 1943. This, together with the capture of Tunis the same day, effectively ended the Tunisian campaign. With those ports in Allied hands, all Axis forces remaining in North Africa were forced to surrender within days.

At the end of May 1943, Technician 5th Grade Park and a handful of other men remained on detached service in Bizerte, Tunisia, while the rest of the company headed to the Fifth Army Tank Destroyer Training Center near Sebdou, Algeria. There, the unit began the process of converting from the M3 Gun Motor Carriage to the 3-inch Gun Motor Carriage M10. Park rejoined the main body of the unit at Sebdou on July 5, 1943. Four days later, for unknown reasons, Park and three other tech 5s from the Bizerte detail were reduced to the grade of private.

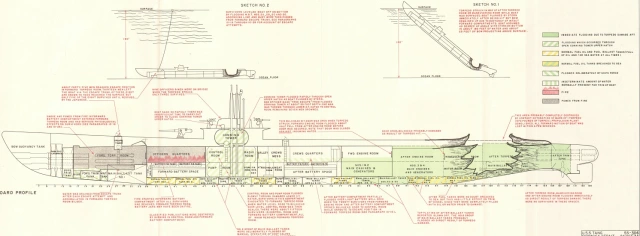

The M10’s M7 3-inch gun was capable of dispatching most contemporary German armored vehicles, although the newer Panther and Tiger tanks were a greater challenge (especially at longer ranges and in instances the enemy could only be attacked from the front, which was protected by heavier armor). The Tiger’s armor was approximately three times as thick as an M10’s and its powerful 88 mm cannon could have knocked out an M10 from any combat range, regardless of the angle. The M10 was similarly mismatched against the Panther.

Compared to contemporary tanks, the M10 had several vulnerabilities. In addition to having light armor, the M10’s turret had no roof and lacked periscopes—only the driver and assistant driver had them—making the crew far more vulnerable to artillery and small arms fire during battle. The M10 was usually equipped with only a single machine gun (a .50 caliber mounted on the rear of the turret). In contrast, the principal American tank, the M4 medium tank (now popularly known by its British nickname, the Sherman) had an enclosed turret. The M4 was also far better equipped to deal with enemy infantry since it was equipped with not only a machine gun mounted on the turret (usually a .50) but also a .30 caliber machine gun in a co-axial mount with the main gun and another .30 mounted in the hull.

Although tank destroyers were designed primarily as a defensive weapon to counter large groups of enemy tanks, they were rarely used that way in combat. This was evident as early as the Tunisian campaign. In a letter home on May 17, 1943, Captain Newton—now Private Park’s company commander—grumbled: “I’d like to be back at [Camp] Hood, so I could tell the brass hats what we need. They’re preparing us to fight one way. We are used by higher authorities in every other way.”

On October 9, 1943, Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion moved north from Sebdou to a staging area at Fleurus, near Oran, Algeria. The company was split into several groups for transport to Italy. A detachment of two officers and 33 enlisted men, including Private Park, left the main body of the unit on October 10, 1943. On October 18, 1943, they sailed from Oran or nearby Mers-el-Kébir, Algeria, arriving in Italy on October 31, 1943. They disembarked on November 3, 1943. Private Park rejoined the main body of Company “C” upon its arrival in Naples on November 10, 1943.

After performing military police duty in Naples, the 894th Tank Destroyer returned to combat on the Cassino front in late December 1943. During this period, they were effectively acting as self-propelled artillery rather than in an antitank role.

On January 9, 1944, Company “C” was withdrawn in preparation for an amphibious operation intended to bypass the German Gustav Line: Operation Shingle. Most of the company arrived at the Anzio beachhead on the fourth day of the invasion, January 25, 1944.

On the night of February 3–4, 1944, German forces launched an attack intended to crush the Campoleone salient, where Company “C” was supporting the British 1st Infantry Division. Some of Company “C,”—likely including Private Park’s platoon—were briefly trapped behind enemy lines and barely managed to escape encirclement. After setting up new positions, Companies “B” and “C” of the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion were instrumental in defeating German forces near Aprilia (“The Factory”). According to the S-3 periodic report written by Captain (Later Colonel) Paul A. Baldy (1918–2008) covering the afternoon of February 3, 1944, through the afternoon of February 4, 1944:

The enemy counterattacked very strongly during the period. “B” & “C” Companies participated very actively in repulsing the attack. “C” Company destroyed four (4) Mark VI [Tiger] tanks. These have been confirmed by the British. One towed AT [antitank] gun was destroyed while its crew was attempting to get it into firing position. Two destroyers held off the German infantry with their 50 cal. for two hours. Many casualties were inflicted. We lost two M 10’s– destroyed and one captured in this action. Two enemy occupied houses were also fired into by “C” Company.

After the failure of the German counterattacks, months of static warfare followed. The Anzio beachhead was a miserable and very dangerous place. Even when the front lines were quiet, the Germans constantly bombarded the Allied positions, often employing powerful railway guns, as well as aircraft armed with the deadly antipersonnel weapons known as “butterfly bombs.”

Park was promoted twice during the Anzio campaign. He was promoted to private 1st class on March 11, 1944. Then on March 16, 1944, shortly before the long-anticipated breakout from Anzio, Park was promoted to corporal—equivalent to previous rank of technician 5th grade. As a corporal, he likely had the duty of antitank gunner.

The Fourth Assault on Villa Crocetta

On May 26, 1944, during the long-anticipated breakout from Anzio, Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion was assigned to support the 168th Infantry Regiment of the 34th Infantry Division during operations against the Caesar Line in the Alban Hills near Lanuvio, Italy. Two days later, 1st Battalion of the 168th Infantry Regiment began a series of unsuccessful assaults on a German stronghold known as Villa Crocetta (located at approximately 41° 39’ 45” North, 12° 42’ 49” East along the present day Via di Colle Crocette, southeast of Lanuvio). The Fifth Army History Part V: The Drive to Rome, summarizing the 168th Infantry Regiment history for May 1944, described the fortifications as follows:

On the right the 168th Infantry faced two particularly nasty strongpoints: Gennaro Hill and Villa Crocetta on the crest of Hill 209. As our troops approached either point, they had to cross open wheat fields on the neighboring hills, then make their way across the draws formed by the tributaries of Presciano Creek, and finally attack up steep slopes to their objectives. The German line was marked by a trench five to six feet deep which ran across Hill 209 and on past the southern slopes of Gennaro Hill. Based on this trench and its accompanying dugouts, machine guns were emplaced to command the draws, and mortars were located in close support. At Hill 209 the enemy also had wire nooses, trip wire, and single-strand barbed wire to break the impact of our charge.

According to the “History of the 168th Infantry Regiment for May 1944,” by the afternoon of May 29, 1944, the men of 1st Battalion were close to exhaustion. They had made two assaults on May 28, 1944, and a third on the morning of May 29th. Perhaps the most demoralizing thing was that one attack was going well until they were forced to retreat due to poorly coordinated friendly artillery fire.

Lieutenant Colonel Wendell H. Langdon (1908–1984) ordered 1st Battalion to make a fourth attack on Villa Crocetta, which began at 1315 hours on May 29, 1944. Unlike the previous three attacks, this one was made with the “support of four M10 tank destroyers and three light tanks”—the latter likely from Company “D,” 191st Tank Battalion.

That afternoon, Corporal Park shared the turret of his M10 tank destroyer with two men: 1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie (1914–1944) and Sergeant Robert D. Lightsey (1911–1944). Seated below and to the front of them in the hull of the M10 were the driver, Corporal John F. Perkins (1908–1984), and the assistant driver, Private Reamer H. Conner (1923–1998).

Lieutenant Jarvie, who hailed from New Jersey, had fought with Company “C” as a platoon leader in the Tunisian campaign before transferring to Headquarters Company on September 13, 1943. Early in the Anzio campaign, on February 3, 1944, Jarvie returned to Company “C” as a platoon leader after another officer was wounded.

Sergeant Lightsey, like Corporal Park, was from Florida. Both men had been subjected to the peacetime draft. In fact, Lightsey was inducted at Camp Blanding only one day earlier than Park.

If their platoon leader had not been aboard, Sergeant Lightsey would have been commanding the M10 and Corporal Park would have been serving as gunner. It is likely that with the platoon leader aboard, Sergeant Lightsey would have assumed the role of gunner, with Corporal Park moving to the assistant gunner (loader’s) position.

Unbeknownst to the officers planning the assault, German strength was higher than anticipated. According to the 168th Infantry Regiment’s S-3 journal, after the attack the battalion obtained intelligence indicating that the Germans had “8 tanks dug in at Villa Crocetta and a Bn [battalion] in strength defending with a Bn in reserve.” Eight enemy tanks were simply too much for four M10s to reasonably handle.

Compounding matters was the fact that according to the 168th regimental history, “After the failure of the third attack on the Villa, [1st Battalion’s] Company ‘A’ and Company ‘C’ were approaching the point of complete demoralization” and most of them refused to advance. Only Company “B” made any significant headway against the objective.

In a statement reproduced in Sergeant Lightsey’s Individual Deceased Personnel File (I.D.P.F), the M10’s assistant driver, Private Reamer H. Conner, wrote that they had been attacking German infantry when they were notified by radio of an imminent friendly artillery strike. They withdrew and replenished their ammunition supplies from a halftrack commanded by Staff Sergeant West R. Lyon (1916–1988). 1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment’s S-3 (operations and training officer), Captain William W. Galt (1919–1944), was observing the action with Lyon and accompanied the renewed attack.

Conner continued, “We moved up again and we were crossing a ditch and threw a track. We finally got the track on with a bar, Sergeant Lightsey put a new antenna on (broken one was shot off).” At some point—probably after the track was repaired, based on the survivors’ statements—Captain Galt boarded the M10, standing on the rear deck and manning the tank destroyer’s .50 machine gun as they approached German-occupied buildings and trench line. The M10 also destroyed a German antitank gun spotted by an infantryman accompanying the assault, Technical Sergeant Ervin M. Frey (1919–1991).

Private Conner recalled that the M10 advanced through an olive grove and, spotting German soldiers in a trench, they “cleaned up the Infantry[.]” The German infantry took heavy casualties—at least 15 and as many as 80 were killed or wounded, depending on the account.

Then, around 1420 hours, disaster struck. In his 1977 book, Cassino to the Alps, Ernest F. Fisher, Jr., drawing on postwar interviews with German sources, wrote that

the penetration at Villa Crocetta and the earlier abortive thrust [by 2nd Battalion] on San Gennaro Hill had hit the Germans at a critical point, along the boundary between the 3d Panzer Grenadier and the 362d Infantry Divisions. Unless quickly contained, the thrusts might develop into a breakthrough of the Caesar Line southeast of Lanuvio. To forestall such a blow, [General Alfred] Schlemm, the I Parachute Corps commander, ordered the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division, the stronger of the two German units to counterattack […] Spearheaded by a rifle company, supported by four self-propelled guns[.]

According to the contemporary 168th Infantry history, the 1st Battalion intelligence officer observed

an estimated company of Germans, supported by four tanks, counter-attacking down the valley with bayonets fixed. One of the tanks pulled up behind the Villa and fired a shell through the turret of a tank destroyer, killing the battalion operations officer who had been firing the tank destroyer’s 50 callibre [sic] machine gun at the retreating Germans.

In a statement reproduced in Sergeant Lightsey’s I.D.P.F., Corporal Perkins recalled that

After we picked up this Infantry Captain, we travelled about one hundred (100) yards before we were hit. The Captain was standing on the back of the Tank Destroyer when he got killed. He was firing the .50 caliber. We were sitting still when the tank [sic] was hit. The shell came through the turret. I saw Lt. Jarvie and Sergeant Lightsey fall to the bottom of the turret. In about four or five seconds, the tank caught fire and I went out the turret on the left side after crawling over them (both of them). I’m certain that they were both dead.

Private Conner recalled that he was initially unaware that the M10 had been hit:

I thought it was a .50 caliber shooting in our turret at first. As the hot lead sprayed around, Corporal Perkins shouted that he was hit and told us to get out. I jumped out when it blazed on the Ass’t. drivers side. I went out the turret and started running. Perkins stopped me and put the fire out in my hair. Then we crept, crawled, and ran to get into a ditch. Then we crawled over a small hill to where the Infantry was in a wheatfield and then to the next wadi where the medic was. I don’t remember feeling anything. I had my eyes closed because it was blazing there and I didn’t want them burnt.

The 168th Infantry Regiment history ruefully noted that the German “counter-attack, supported by tanks, was too strong for the twenty men left to hold the hill.” The surviving American infantry retreated.

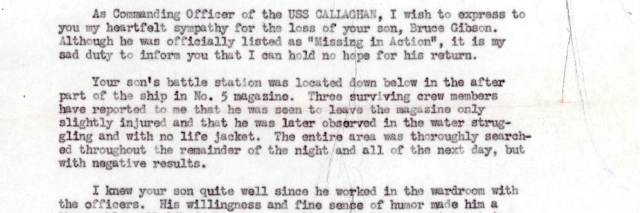

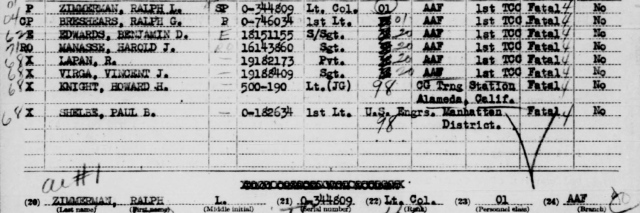

It’s not clear if the same German shell that killed Lieutenant Jarvie and Sergeant Lightsey also claimed the lives of Corporal Park and Captain Galt (whose bodies were located next to the burned out M10), but Corporal Perkins and Private Conner were the only survivors of the crew. Corporal Perkins later told his family that he and Conner hid from the Germans for a time—close enough to them laughing—before they were able to escape back to American lines.

Aftermath & Repatriation

Private Conner was hospitalized for wounds to his head as well as his hands, and Corporal Perkins for wounds to his thoracic wall and hands. Both men were hospitalized until July 1944. After they were discharged from the hospital, both men rejoined the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion and continued to serve through V-E Day. Captain Galt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, though it appears that the members of the M10 crew received no decorations other than the Purple Heart.

1st Lieutenant (later Captain) Thomas K. LeGuern (1911–2004), the Company “C” executive officer, later wrote that he returned to the scene of the battle after the Germans were driven back: “On 2 June 1944, with Sgt. Lyon (now Lieutenant), I went to Villa Crocetto, [sic] where I identified Corporal Park and the body of an unidentified American Captain […] recognized by Lt. (then Sergeant) Lyon, as being Capt. Galt[.]”

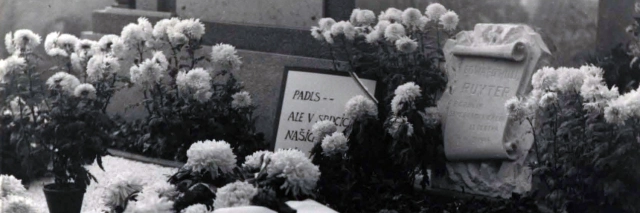

Letters found on Corporal Park’s body confirmed that Lieutenant LeGuern’s identification was correct, and Corporal Park was buried at the U.S. Military Cemetery Nettuno (Plot 2R, Row 57, Grave 6004).

After the war, Park’s family requested his body be repatriated to the United States. The Miami Herald reported on July 7, 1948, that Corporal Park and nine other fallen men from the Miami area were en route aboard the Carroll Victory. After services at the King Funeral Home on August 12, 1948, Corporal Park was buried at the Miami City Cemetery. Corporal Park is also honored on a war memorial dedicated in Miami Springs in May 1945.

Notes

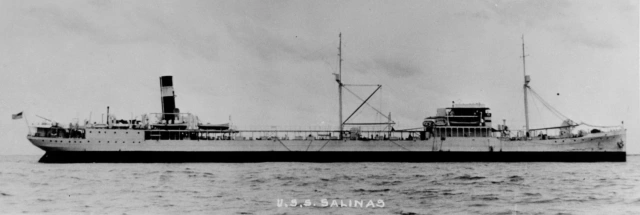

Journey from Algeria to Italy

Company “C” morning reports state that Park’s detachment sailed aboard the Gordon G. Curtis. I have not been able to confirm the existence of a vessel by that name, although there was a Liberty ship in service at that time was a similar name, the Charles Gordon Curtis. Anecdotally, that vessel was indeed involved in transportation between Algeria and Italy in the fall of 1943.

Three Enemy Tanks Destroyed?

A July 7, 1948, article in The Miami Herald stated that Corporal Park’s “tank destroyer was credited with knocking out three German tanks in Africa and Sicily.” Corporal Park did not participate in the invasion of Sicily, so presumably that should have been Italy. It is difficult to confirm or refute this claim. Fighter units may have kept records of pilots’ victory claims, but armored units did not. Surviving unit documentation or newspaper reports sometimes documents that a particular crew knocked out an enemy tank, but I have found none that documented Corporal Park or his crew doing so.

A possible source of the claim is a newspaper photo of Private Park at the Anzio beachhead, speaking with another Floridian from his company, Private 1st Class Paul O. Elder (1918–1991). Elder had been inducted at Camp Blanding the day before Park had. Elder was the gunner on Sergeant Eugene K. Holsonback’s M10 at Anzio on February 4, 1944, and knocked out a Tiger tank during a short, violent battle that claimed the life of his platoon leader, 1st Lieutenant Wallace C. Forbush, Jr.

When the photo of Park and Elder was printed in the Miami Daily News on March 21, 1944, Dorothy Garfunkel wrote:

The subject under discussion is the intricacies of Elder’s third German tank kill on the Anzio beachhead.

His tank destroyer previously knocked out two German tanks on the Fifth army front below Rome, according to a dispatch received from that area.

It seems likely that the 1948 article incorrectly referenced the 1944 photo, but conflated the fact that Elder had three tank kills with Park’s record, even though Park was a member of another crew.

Enemy Tanks or Self-Propelled Guns at Villa Crocetta?

Sources disagree about whether the M10 was knocked out by a tank or self-propelled artillery. I have not yet been able to examine the report that Fisher used to provide the German perspective of the battle, but it seems the vehicle in question was an assault gun. American sources frequently identified such vehicles as tanks. German assault guns looked very similar to tanks, aside from having their cannons in casemates rather than turrets.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to John R. Park and Magaly V. Park for information and photos about Corporal Park and his family. Thanks also go out to the Newton family for the use of their photos.

Bibliography

“10 Miami War Dead Are Returned.” The Miami Herald, July 7, 1948. Pg. 9-A. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/91750811/corporal-park-body-returned/

Applications for Headstones, compiled 1/1/1925–6/30/1970, documenting the period c. 1776–1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_2421402106_0393-00959

Chase, Patrick J. Seek, Strike, Destroyer: The History of the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion in World War II. Gateway Press, 1995.

Company morning reports for Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. December 1942–June 1944. National Personnel Records Center.

“CPL Elmer Franklin Park.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37617264/elmer-franklin-park

Fifth Army History Part V: The Drive to Rome. Publisher unknown. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/5th-army-history-part-v-chapter-vii.pdf

Fisher, Ernest F., Jr. Cassino to the Alps. Originally published in 1977, republished by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1993. https://history.army.mil/html/books/006/6-4-1/CMH_Pub_6-4-1.pdf

“Food, Disturbed Sleep At Maneuvers Gripes Soldier.” The Miami Herald, October 5, 1941. Pg. 6-C. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/54414986/elmer-park-94th-later-894th-tank/

Garfunkel, Dorothy. “Florida Pals Meet On Front In Italy.” Miami Daily News, March 21, 1944. Pg. 4-A. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/41202816/elmer-f-park-894th-tank-destroyer/

“The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment from May 1, 1944 to May 31, 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/168th-infantry-regiment-history-may-1944.pdf

“Legion Honors 3 War Dead.” Miami Daily News, May 24, 1945. Pg. 4-B. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/91706075/elmer-park-honor/

Park, John R. Email correspondence on January 3, 2022, and January 20, 2022.

“Rites Set For Three Heroes of World War.” The Miami Herald, August 10, 1948. Pg. 6-B. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/91749796/elmer-park-funeral/

Robert D. Lightsey Individual Deceased Personnel File. National Archives. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2021/01/lightsey-robert-d-idpf.pdf

Silverman, Lowell. “1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie: Jack in the Alice Griffin Letters.” 32nd Station Hospital website, March 25, 2020. Updated December 28, 2021. https://32ndstationhospital.com/2020/03/25/1st-lieutenant-john-s-jarvie-jack-in-the-alice-griffin-letters/

Silverman, Lowell. “Baker D. Newton.” TankDestroyer.net, February 20, 2020. https://tankdestroyer.net/honorees/n/1158-newton-baker-d-894th-805th

Silverman, Lowell. “Captain William W. Galt: ‘Always Out In Front’.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society website, May 29, 2021. https://www.cmohs.org/news-events/medal-of-honor-recipient-profile/captain-william-w-galt-always-out-in-front/

Silverman, Lowell. “Sergeant Robert D. Lightsey (1911–1944).” Delaware’s World War II Fallen website, December 28, 2021. Updated December 30, 2021. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2021/12/28/sergeant-robert-d-lightsey/

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

“Table of Organization and Equipment No. 18-27: Tank Destroyer Gun Company, Tank Destroyer Battalion, Self-Propelled.” War Department, March 15, 1944. Military Research Service website. http://www.militaryresearch.org/18-27%2015Mar44.pdf

Tenth Census of the State of Florida, 1935. State Library and Archives of Florida, Tallahassee, Florida. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1506/images/CSUSAFL1867_089270-00644

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531932_00416

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00582-00119

World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005150569_00800

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=34051507&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=4497077

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Florida, 10/16/1940–3/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44005_10_00041-00726

Last updated on February 5, 2022

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.