| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Pennsylvania, Delaware | Engineer’s assistant |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32488159 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | 857th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 492nd Bombardment Group (Heavy) |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 611 (aerial gunner) | European air campaign |

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my article about Staff Sergeant George H. Devine, another Delawarean who served in the 492nd Bomb Group.

Early Life & Family

Clyde Harold Breckenridge was born at 221 Wyoming Avenue in Kingston, Pennsylvania, on March 12, 1924. He was the second child of George Clyde Breckenridge (then a clerk and later a life insurance agent, 1900–1949) and Pearl Anna Breckenridge (née Learn, 1898–1994). Breckenridge’s father had served in the Medical Detachment of the 109th Field Artillery during World War I and was injured by exposure to mustard gas on October 4, 1918.

Breckenridge had an older sister and two younger sisters.

The Breckenridge family was recorded on the census on April 9, 1930, living on Lehigh Lane in Kingston. Census records state that as of April 1, 1935, the family was living in Plymouth, Pennsylvania. They were recorded again on April 4, 1940, living at 45 Center Street in Forty Fort, Pennsylvania. The family moved to Wilmington, Delaware, shortly thereafter.

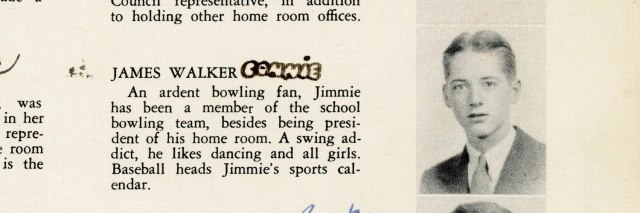

Breckenridge graduated from Pierre S. duPont High School on June 10, 1942. Later that month, on June 30, 1942, when he registered for the draft, Breckenridge was living at 2607 (North) Madison Street and working in blueprinting for the DuPont Company at 10th and Market Streets in Wilmington.

In his mother’s statement to the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission, she listed Breckenridge’s occupation as engineer’s assistant. His enlistment data card listed his occupation as machinist. Journal-Every Evening stated that after graduating high school, Breckenridge “was employed by the engineering department of Dravo Corporation” prior to entering the service. The paper also reported that he “was a member of the Hanover Presbyterian Church.”

According to his military paperwork, Breckenridge stood five feet, 4½ inches tall and weighed 146 lbs., with red hair and brown eyes.

Military Training

Breckenridge was drafted early in 1943. His enlistment data card stated that he was inducted into the U.S. Army in Camden, New Jersey, on January 20, 1943. According to military records, Breckenridge went on active duty at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on January 27, 1943. One week later, he departed for the U.S. Army Air Forces Miami Beach Training Center, Florida, where he attended basic training from February 5–26, 1943. Breckenridge then headed west to the Harlingen Aerial Gunnery School in Texas (March 1, 1943 – April 10, 1943).

Breckenridge arrived at Keesler Field, Mississippi, on April 12, 1943. He completed the Airplane Mechanics course there on September 9, 1943. He departed Keesler on September 20, 1943, and was stationed at several other bases: Salt Lake City, Utah (September 24–29, 1943); Mountain Home, Idaho (October 2–29, 1943); and Wendover Army Air Field, Utah (October 30, 1943 – November 26, 1943). A private 1st class by September 9, 1943, Breckenridge was promoted to sergeant on an unknown date prior to January 26, 1944.

On November 28, 1943, Breckenridge arrived at Casper Army Air Base, Wyoming. At the 331st Combat Crew Training School there, he joined a Consolidated B-24 Liberator crew led by 2nd Lieutenant Alvin M. Murray (1922–1944). On January 26, 1944, his crew was transferred to the nascent 492nd Bombardment Group (Heavy) at Alamogordo, New Mexico, per Special Orders No. 26, 331st Combat Crew Training School. At the time, Sergeant Breckenridge’s Military Occupational Specialty (M.O.S.) was recorded as 748 (airplane mechanic–gunner or aerial engineer–gunner). After arriving on February 2, 1944, the crew was assigned to the 857th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy).

That spring, the 492nd Bomb Group was dispatched to England to join the Eighth Air Force. Breckenridge and his crew were assigned a B-24J (serial number 42-110151, nicknamed G.I. Joe) for their overseas journey. Sergeant Breckenridge’s M.O.S. was listed as 611 (aerial gunner) by that time. After preparing their aircraft for the journey at Herington Army Air Field, Kansas, during April 1–8, 1944, Breckenridge’s crew flew to England via the southern route, with stops at Morrison Field in Florida (now Palm Beach International Airport), the Caribbean, Brazil, and North Africa. Breckenridge’s mother stated that her son arrived in England on April 21, 1944. That is consistent with the 492nd Bomb Group history, which reported that “All 73 aircraft in the Group landed safely between April 18 and May 1[.]”

In early May 1944, the 492nd Bomb Group went on some training missions in England, though their acclimation period before entering combat was somewhat abbreviated as the group history explained: “Although the Group had been scheduled to go to Scotland for the usual pre-combat training period, it is significant that the 492nd was considered by higher command to be sufficiently well trained to warrant its being sent directly to its combat station in East Anglia,” the Royal Air Force field at North Pickenham.

Combat Over Europe

The 492nd Bomb Group’s first combat mission took place on May 11, 1944. Breckenridge and his crew flew their first mission the following day aboard G.I. Joe during a raid on the oil refinery at Zeitz, Germany. On May 13, 1944, they flew another mission, utilizing an unknown B-24 during an attack on the airfield at Tutow, Germany. They did not participate in the group’s fourth mission on May 14, 1944.

During the 492nd Bomb Group’s first four missions, it suffered only two fatalities. However, its losses during the next raid—the 492nd’s fifth and Breckenridge’s third—were disastrous. On the morning of May 19, 1944, Sergeant Breckenridge and his crew boarded G.I. Joe for the final time, with Breckenridge most likely manning the ball turret.

26 B-24s from the 492nd Bomb Group took off, accompanied by two pathfinder aircraft from the 44th Bomb Group. The Eighth Air Force dispatched a total of 888 bombers, targeting the enemy airfield at Waggum and the nearby aircraft factory at Braunschweig (Brunswick), Germany. The formations became disorganized during their approach to the target. Paul Arnett explained in his article “Mission 5 — Friday, 19 May 44 — Brunswick”:

Because of the Luftwaffe attacks, half of the 2nd Air Division were approaching Brunswick from a direction different from the briefed route. The primary target wasn’t accessible from that angle, so the 20th and 14th Wings passed over the flak filled skies without dropping their bombs (the 492nd is in the 14th Wing). They circled around for another shot at it only to find themselves on a collision course with the 96th Wing who were coming in on schedule. And the 96th would be followed by the 2nd Wing. The 20th circled around for a third attempt. The 14th decided it had enough of the comedy so they flew to the southwest corner of the city and took out a railroad marshalling yard instead.

First during the run into Braunschweig and again coming off the target, German fighters pounced on the 492nd’s B-24s when they were separated from the protection of their escorting fighters.

2nd Lieutenant George B. Haag provided a brief eyewitness statement included in Missing Air Crew Report (M.A.C.R.) No. 5241:

A/C [Aircraft] No. 0151, piloted by Lt. Murray, was attacked by 50 e/a [enemy aircraft] (Me 109’s and FW 190’s) at 1250 in the vicinity of Hannover [sic]. The a/c dropped out of formation and a few seconds later exploded in mid-air. No parachutes were seen to open.

In fact, four men managed to parachute to safety before the plane exploded, one of whom, Sergeant Richard E. Statham (1922–1992), was severely wounded and ended up losing a leg.

Both pilots, 2nd Lieutenant Murray and 2nd Lieutenant Kermit W. Anderson (1918–1944), were killed, but there were two survivors from the front of the plane: 2nd Lieutenants Glen R. Rosenberry (bombardier, 1921–2014) and Kenneth A. Schwartz (navigator, 1916–1992). In a postwar letter to Sergeant Breckenridge’s mother, 2nd Lieutenant Anderson’s wife, Jean, quoted a letter from Schwartz dated June 6, 1945, which provided an account of the last mission:

We were bombing near Brunswick that day & were hit by fighters before we got to the target. We lost one engine due to this action. We got a little behind the formation but Murray & Andy were able to get this engine feathered & we were back in formation again before we got to the target. Over the target the ship was hit again by a near miss of flak which must have done some damage. It wasn’t visible to me tho’, as I was riding in the nose at the ship with Rosie. A small fragment hit me in the leg but didn’t do much damage. After we left the target another engine caught fire. Shortly after this Murray gave the signal to bail out & Rosie & I left the ship out the nose wheel door.

Concluding his letter, Schwartz added: “We had a good crew & everyone did his best. You can be very proud as everyone did a good job altho’ the sacrifice was great.”

Since he was at the front of the bomber, Schwartz did not witness Sergeant Breckenridge’s fate. There were only two survivors were from the back of the aircraft where Sergeant Breckenridge had been: Sergeant Richard E. Statham and Staff Sergeant Waukeen C. Gatlin (1917–1989).

In a casualty questionnaire attached to Missing Air Crew Report No. 5241, Staff Sergeant (then Sergeant) Statham wrote of Sergeant Breckenridge that “afte[r] we hit the target he came up out of the ball” turret, but that Breckenridge “was killed inst[antly]” near one of the waist windows. The M.A.C.R. did not include a statement by Staff Sergeant Gatlin, but Schwartz and Rosenberry wrote that Gatlin told them that Breckenridge was dead before Gatlin and Statham bailed out.

Captured German records stated that the B-24 crashed around 1400 hours, about 50 miles south of Hanover. The crash site was about half a mile west of Vardeilsen, south of the Vardeilsen-Amelsen road.

The 492nd Bomb Group lost eight crews from the 26 B-24s dispatched on the mission, an astonishing casualty rate of nearly 31%. Indeed, the group’s casualty rate for the mission was higher than the Eighth Air Force’s during the second raid on Schweinfurt seven months earlier. (That earlier mission, subsequently dubbed Black Thursday, took place before the Allies had fighters with the range to escort bombers all the way to their targets and back.)

The 492nd Bomb Group history tried to put a positive spin on what happened:

The 492nd were by no means “sitting ducks”, however, for they made claims to 11 enemy aircraft destroyed, one proba[b]le and one damaged. (All but one “destroyed” and one “probable” were later confirmed.) The Group proved in this ordeal by fire that it could “take it and also dish it out” and was a real fighting unit.

Unfortunately, the May 19 raid was merely the beginning of the 492nd Bomb Group’s misfortunes. In three months of combat, the 492nd sustained so many casualties that it was effectively disbanded and its surviving personnel and aircraft transferred to other units. The 492nd’s identity was then assumed by a special unit previously known as the 801st Bombardment Group (Provisional). Nicknamed the Carpetbaggers, their night missions included not only bombardment but also dropping operatives and cargo into occupied Europe.

Sergeant Breckenridge’s parents learned that their son was missing on or about June 3, 1944, when the War Department sent a telegram. On July 13, 1944, the War Department received confirmation of Breckenridge’s death from the Germans via the International Red Cross.

The Army sent Breckenridge’s personnel effects to his parents. The inventory was typical for an Eighth Air Force aviator (such as clothing, a wristwatch, a knife, a wallet, and a photo album) with one notable exception: Sergeant Breckenridge brought a pair of cowboy boots with him to England!

After the tragedy, the families of the crew members exchanged letters sharing information and eventually condolences. In a letter to Sergeant Breckenridge’s mother, Anita M. Hernandez, mother of Staff Sergeant Elias M. Hernandez (1923–1944), wrote:

My dear Mrs. Breckenridge,

I am very sorry to learn from your letter that your son was reported killed in action. There aren’t words to say in this times to comfort our hearts that are aching for our loves one that are gone. It looks like the whole world has come to an end. But we must go on and be brave like they were. I don’t know what to believe whether he is dead or alive. I don’t know and yet someday, — maybe we’ll see them again.

My son was such a good boy, that’s why I am still hoping so hard and praying it’s a mistake, that God is keeping them safe from the enemy.

Right now I feel like going to bed an staying there for awhile. I feel so weak. I guess you must feel the same. Please keep on writing it’s a comfort to write to each other. May God give you the strength to bear your sorrow[.] My heart goes to your[s] in this times.

Your sincerely

Mrs. Anita M. Hernandez

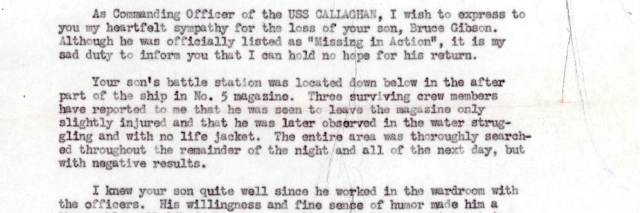

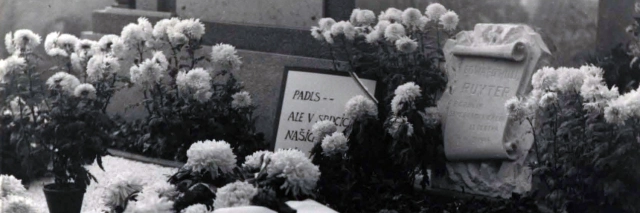

The Germans had located Sergeant Breckenridge’s body one week after the crash and buried him with the other members of his crew in the Vardeilsen cemetery. Although German records make it clear that Breckenridge was recovered wearing his dog tags, they apparently did not bury the tags with him, since graves registration personnel were unable to identify him when the burial site was exhumed after the war. The six fallen members of the crew were temporarily reburied at the U.S. Military Cemetery Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium.

Breckenridge’s mother and Representative J. Caleb Boggs (1909–1993), whose own brother had been killed in World War II, made several inquiries during the prolonged recovery and identification process. Ultimately, only Staff Sergeant Hernandez was individually identified. He was buried at what is now known as the Netherlands American Cemetery. The other five—Sergeant Breckenridge, 2nd Lieutenants Anderson and Murray, Staff Sergeant Wesley F. McMullen (1920–1944), and Staff Sergeant Lowell S. Stillflew (1921–1944)—were repatriated to the United States. On March 7, 1950, they were buried at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 34, Graves 4727 and 4728).

Crew of B-24J G.I. Joe on May 19, 1944

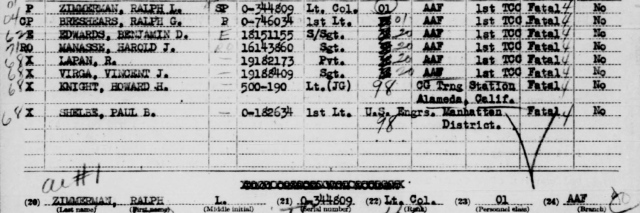

The following list was adopted from Missing Air Crew Report No. 5241 with grade, name, service number, position, and status (killed or captured). At least one and probably two crew positions listed below are inaccurate: see the Notes section for further information.

2nd Lieutenant Alvin M. Murray, O-809026 (pilot) – K.I.A.

2nd Lieutenant Kermit W. Anderson, O-692846 (copilot) – K.I.A.

2nd Lieutenant Kenneth A. Schwartz, O-691815 (navigator) – P.O.W.

2nd Lieutenant Glen R. Rosenberry, O-753077 (bombardier) – P.O.W.

Staff Sergeant Lowell S. Stillflew, 16076369 (flight engineer) – K.I.A.

Staff Sergeant Wesley F. McMullen, 31196750 (radio operator) – K.I.A.

Staff Sergeant Waukeen C. Gatlin, 18129740 (right waist gunner) – P.O.W.

Sergeant Clyde H. Breckenridge, 32488159 (left waist gunner) – K.I.A.

Staff Sergeant Elias M. Hernandez, 38428503 (ball turret gunner) – K.I.A.

Sergeant Richard E. Statham, 14056752 (ball turret gunner) – P.O.W.

Notes

B-24J 42-110151 Nickname

Curiously, the 492nd Bomb Group website states that 42-110151 was nicknamed Alvin, while stating that a plane with a similar serial number (44-40151) was G.I. Joe. However, a survivor of the crew, Kenneth A. Schwartz, stated that his plane was nicknamed G.I. Joe, confirmed by the above nose art photo.

Crew Photo

The 492nd Bomb Group website features a crew photo contributed by Ken Schwartz, son of Kenneth A. Schwartz. Although Sergeant Breckenridge is in the photo, the website erroneously identifies him as another member of the crew, Sergeant Richard E. Statham, based on an identification by Statham’s daughter. Lieutenant Schwartz’s notes confirm that Breckenridge is in the photograph but not Statham. Breckenridge’s collection also includes an annotated copy of the photo, which notes on the back that Statham was absent (undoubtedly because he traveled by sea to the U.K.).

Position

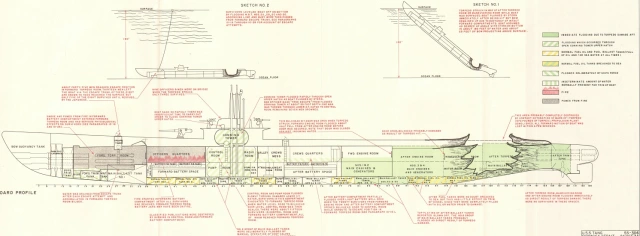

Richard E. Statham stated that Breckenridge had been manning the ball turret but had come up into the fuselage of the aircraft after bombs away. Breckenridge’s mother’s statement (which may have been based on information she obtained from Statham) indicated that her son was manning the ball turret until he relieved a waist gunner.

The crew list in Missing Air Crew Report No. 5241 stated that Breckenridge was the left waist gunner. Curiously, the same list had two ball turret gunners (Staff Sergeant Elias M. Hernandez and Sergeant Richard E. Statham) but no tail gunner, so one of those entries must be in error. According to their draft cards, all three men were short enough to have been ball turret gunners. Statham’s account makes it clear that Breckenridge was in the ball turret for the final mission, but it is possible that it was not his usual position.

Mother’s Statement

Breckenridge’s mother wrote an account of her son’s death in her statement to the Delaware Public Archives Commission:

This mission was completed and the plane returning to Eng. […] Over Hanover 1 motor was knocked out by enemy fighters. Our son left the ball position to relieve waist gunner who went to fix motor. Two more motors were knocked out, plane was set on fire and exploded in mid air. 6 were killed, 4 taken prisoners. Clyde was dead before the 4 bailed out of plane.

It seems this may have been based on information that Breckenridge’s mother received from Richard Statham. (Jean Anderson’s letter thanked Pearl Breckenridge “for telling me Statham’s version of ‘May 19, ’44.’”)

Although fascinating, some details from this account are not accurate. The crew list in the M.A.C.R. does not indicate that the waist gunners were serving as flight engineer. Even if one was acting at the assistant engineer, they could monitor but not repair any engines damaged by enemy fire in flight. It would also make little sense to have a ball turret gunner take over a vacated waist position, since the ball turret had double the firepower and a greater field of fire. It’s possible that Breckenridge exited the ball turret to get his parachute in order to bail out, and briefly manned a waist gun vacated after Statham or Hernandez were hit, prior to being killed by enemy fire himself.

Recovery

The M.A.C.R. includes translations of captured German records. Initially, the Germans located Elias F. Hernandez’s body, as well as four unidentifiable bodies in the wreckage itself. A document dated May 27, 1944, added:

During the salvaging on 26 May 1944 an additional enemy Airman was found dead in a wheat field approximately 500 meters distant from the place of crash: C.H. Breckenridge R CN, Identification Tag: 32488159 T 43-43 A. The above mentioned was buried in the cemetery of the community Vardeilsen, south east corner, on the same day. Turned in personal property will be shipped to the Research Office.

Oddly enough, after the war, recovery personnel were able to identify Sergeant Hernandez’s body but were unable to distinguish Breckenridge’s body from the four severely burned bodies recovered from the crash site, even though the German document proves that he was wearing his dog tags when his body was recovered.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Sergeant Breckenridge’s great-niece, Heather Saum, and to Ken Schwartz, son of the navigator in Breckenridge’s crew, for contributing photos and documents that were invaluable in researching this article. Thanks also go out to Brendan Wood and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photos.

Bibliography

“3 Delaware Soldiers Killed; 2 Are Missing.” Journal-Every Evening, June 13, 1944. Pg. 1 and 6. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/104832270/breckenridge-mia/

Anderson, Jean. Letter to Pearl Breckenridge, October 11, 1945. Courtesy of Heather Saum.

Arnett, Paul. “Mission 5 — Friday, 19 May 44 — Brunswick.” 492nd Bomb Group website. http://www.492ndbombgroup.com/cgi-bin/pagepilot.cgi?page=showMission&mission=05&nav=c2m

Arnett, Paul. “Murray 331st CCTS Crew 102 Summary. 492nd Bomb Group website. http://www.492ndbombgroup.com/cgi-bin/pagepilot.cgi?page=showCCT&cctPage=Murray-CCT&cctCrewNum=102&cctTitle=Murray%20102&nav=c2t

Arnett, Paul. “Murray Crew 709.” 492nd Bomb Group website. http://www.492ndbombgroup.com/cgi-bin/pagepilot.cgi?page=showCrewPage&crewPage=709-Murray&crewTitle=Murray%20709

“Atlas Magazine Editor Injured In Italian Push.” Journal-Every Evening, July 19, 1944. Pg. 1 and 3. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/104832682/breckenridge-kia/

Breckenridge, Pearl P. Clyde Harold Breckenridge Individual Military Service Record, September 1945. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17820/rec/2

Clyde Harold Breckenridge birth certificate. Courtesy of Heather Saum.

Davis, E. L. “Narrative History, 492nd Bombardment Group (H).” June 15, 1944. Reel B0653. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Hernandez, Anita M. Letter to Pearl Breckenridge, c. July 1944. Courtesy of Heather Saum.

Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_1220706333_0445-00533

Long, Hugh R. “Missing Air Crew Report No. 5241.” May 25, 1944. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. The National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/90978312

“Richard E Statham.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/144408218/richard-e-statham

Schwartz, Ken. Electronic correspondence, July 2, 2022.

Silverman, Lowell. “Staff Sergeant George H. Devine (1909–1944).” Delaware’s World War II Fallen website, December 21, 2021. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2021/12/21/staff-sergeant-george-h-devine/

“Special Orders Number 26, 331st Combat Crew Tng School AAB, Casper, Wyoming.” January 26, 1944. Reel B0653. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Special Orders Number 91, 231st AAF Base Unit (CCTS (VH)).” March 31, 1944. Reel B0653. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4639400_00465

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/M-T0627-03551-00091

“W C Gatlin.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/71358141/w-c-gatlin

World War I Veterans Service and Compensation File, 1934–1948. Record Group 19, Series 19.91, Records of the Department of Military and Veterans Affairs. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60884/images/41744_2421406272_0989-02462

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32488159&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3099098

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, 10/16/1940–3/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_02_00001-00876

Last updated on July 10, 2022

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.