| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Welder |

| Branch | Service Number |

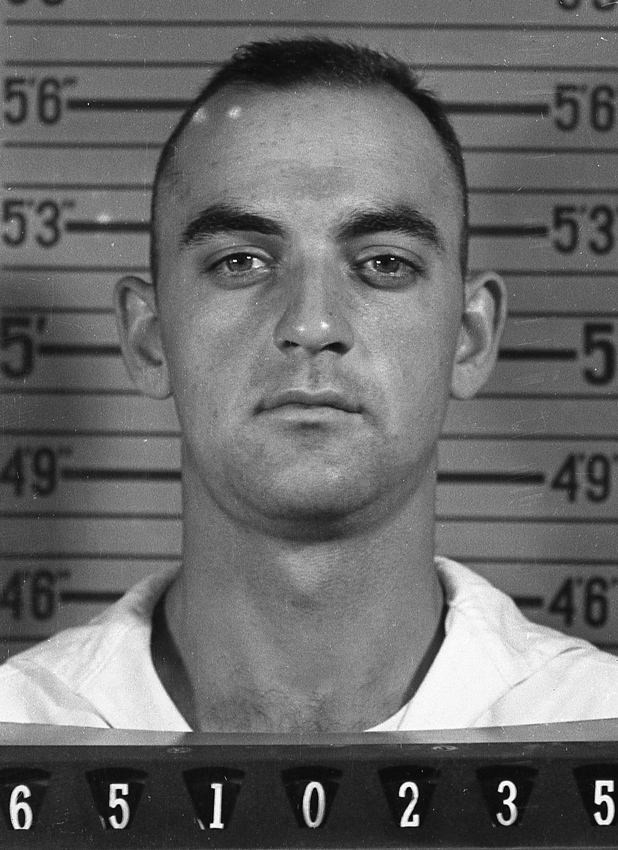

| U.S. Naval Reserve | 6510235 |

| Theater | Assignment |

| Mediterranean | U.S. Navy Armed Guard aboard S.S. John L. Motley |

Early Life & Family

Thomas Charles Davis was born at 329 East 13th Street in Wilmington, Delaware, on September 11, 1921. He was the first child of Leslie Joseph Davis (a laborer at the time, 1902–1986) and Margaret Mary Davis (née Zickgraf, 1901 or 1902–1972).

Davis’s mother’s first husband, Thomas Joseph Davis (1896–1919), served in the U.S. Army during World War I. He served with Company “I,” 59th Pioneer Infantry during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Although hostilities ceased on November 11, 1918, on January 22, 1919, Private Davis and five other men were killed in an explosion attributed to boobytrapped German ordnance. Davis’s mother remarried, to her first husband’s brother.

Davis had two older three-quarter siblings: Michael Davis (1918–1918), who died very young of meningitis and pneumonia, and Margaret M. Davis (later Salvatore, 1919–1984). Davis also had two younger brothers: Leslie Joseph Davis, Jr. (1922–1993) and Michael M. Davis (1925–2013).

The Davis family was living at 1322 East 14th Street in Wilmington as of December 4, 1922, when Davis’s younger brother, Leslie, was born. Their father was described as a boiler helper in a railroad shop at the time. The family was recorded again on the census in April 1930, living at 1504 (North) Claymont Street in Wilmington.

Davis dropped out of school after completing 8th grade at St. Patrick’s Parochial School. His father told the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission that his son served in the Civilian Conservation Corps at some point. By April 1940, when he was recorded on the census living with his family at 1208 East 13th Street in Wilmington, Davis was listed as working as a boilermaker helper. He may have been working at the same factory as his father, who was described as a boilermaker working in Edgemoor, Delaware. This was presumably the Edgemoor Iron Works, where Leslie Davis worked during 1930–1953 according to his obituary.

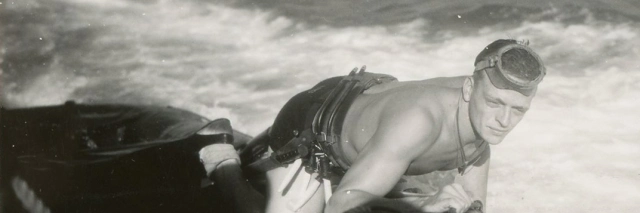

When he registered for the draft on February 16, 1942, Davis was still living with his parents at 1208 East 13th Street and working for the Dravo Corporation nearby. He was a welder according to his personnel file. Similarly, Journal-Every Evening reported that Davis “was an electric welder at the American Car and Foundry Company before enlisting[.]” Davis’s enlistment paperwork described him as standing five feet, seven inches tall and weighing 141 lbs., with brown hair and hazel eyes.

Military Career

Davis volunteered for naval service in Wilmington and enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on August 19, 1942. The following day, he reported for boot camp at the U.S. Naval Training Station, Newport, Rhode Island. Both of his younger brothers followed Davis into the Navy the following year.

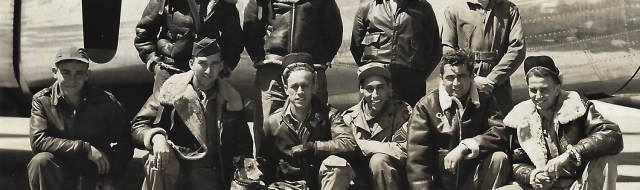

In early October 1942, Apprentice Seaman Davis reported to the U.S. Naval Air Station, New York, New York. On December 1, 1942, Davis was promoted to seaman 2nd class. He transferred to the Armed Guard Center in Brooklyn, New York, on December 10, 1942. The U.S. Navy Armed Guard (U.S.N.A.G.) detachments manned guns aboard American and friendly foreign merchant ships. On December 12, 1942, Davis was promoted to seaman 1st class and assigned to his first vessel. His service record is unclear, but that vessel was likely a tanker, the Panamanian-flagged S.S. Stanvac Manila, which was in New York at that time. (It can only be stated with absolute certainty that Davis was aboard that vessel by May 23, 1943.)

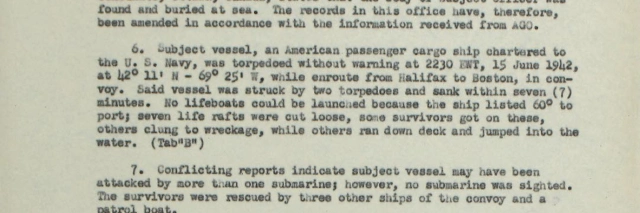

Stanvac Manila spent the end of 1942 and the first four months of 1943 in the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico, before transiting the Panama Canal and heading into the Pacific. On May 23, 1943, she was sunk by Japanese submarine I-17 off New Caledonia with the loss 11 or 12 men.

The Navy later informed Davis’s mother that her son:

Performed credible service as a member of the Armed Guard Crew of a merchant vessel when that vessel was torpedoed by the enemy near Noumea, New Caledonia on 24 [sic] May 1943. Although fully aware of the perilous condition of their ship following its torpedoing, the men of the Navy Gun Crew abandoned ship only when it became impossible to remain aboard any longer.

Coincidentally, the tanker was carrying patrol torpedo boats on deck, which floated free when the ship sank. Crews managed to start several up and assisted in rescuing the survivors. On the afternoon of May 24, 1943, the minelayer U.S.S. Preble (DM-20) arrived on the scene and rescued 85 survivors, including Davis. (Several additional men remained aboard the P.T. boats.). The following afternoon, Preble arrived with the survivors at Nouméa, New Caledonia. Davis remained there from May 25, 1943, until June 6, 1943, when he boarded S.S. Brastiga to return to the United States. On June 21, 1943, Davis left that vessel. On July 16, 1943, one week after returning to the Armed Guard Center in Brooklyn, Davis reported to the U.S. Naval Rest Center, College Arms Hotel, Deland, Florida, “for two weeks of rest and recreation.”

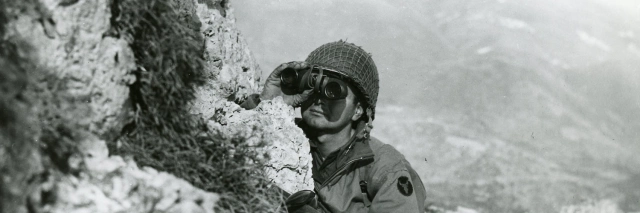

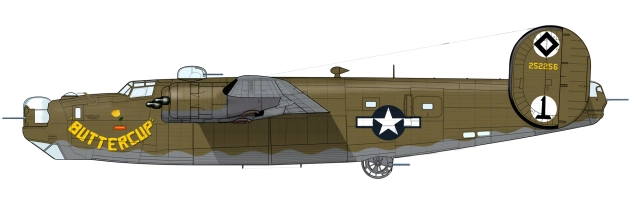

Davis was promoted to gunner’s mate 3rd class on August 1, 1943. Six days later, he was assigned to the U.S.N.A.G. detachment aboard the S.S. Thomas Hart Benton. Benton sailed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, on August 27, 1943. After arriving in Oran, Algeria, the ship spent the fall of 1943 shuttling between various Mediterranean ports. Benton sailed to Malta, followed by Augusta, Sicily, and then Naples, Italy, before returning to Oran.

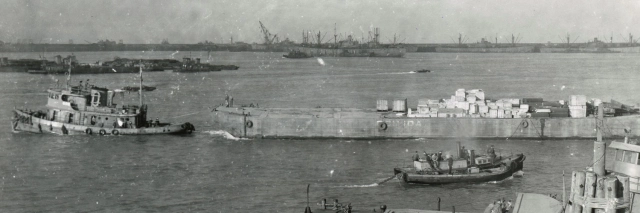

On November 8, 1943, Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class Davis was detached from Thomas Hart Benton and hospitalized at the Naval Dispensary, Receiving Station, Oran, Algeria. The illness would indirectly cost him his life. Later that month, Davis was discharged from the hospital and assigned to the S.S. John L. Motley, a brand-new Liberty ship that had been launched on May 18, 1943. Loaded with a hazardous cargo including explosives, Motley sailed from Oran on November 20, 1943, joining an eastbound convoy before peeling off at Augusta, Sicily. She then joined another convoy that departed Augusta on November 26, 1943, arriving two days later at Bari, on the east coast of Italy. Another Liberty ship accompanying the Motley on both legs was destined for infamy: S.S. John Harvey’s cargo included aerial bombs filled with mustard gas, stockpiled for retaliatory purposes in the event that the Germans reintroduced chemical warfare to Europe.

Air Raid on Bari

On December 2, 1943, Davis was aboard the S.S. John L. Motley at Bari, where the ship was waiting to offload her cargo. The port was crammed with ships still waiting to be unloaded. Around 1930 hours that evening, the Germans launched a surprise air raid on the poorly defended port. 105 Ju 88s bombed the crowded harbor virtually unopposed by either Allied antiaircraft guns or night fighters. The results were devastating.

In his book, Disaster at Bari, Glenn B. Infield recounted what Captain Otto Heitmann of the Liberty ship S.S. John Bascom saw:

The first explosion was off the harbor, in the city […] Heitmann did not have time to stand and watch the burning city, however, since the German bombers had already discovered their error and were “walking” the bombs out into the water straight toward the line of ships anchored at the East Jetty. Yard by yard the bombs came closer, working their way up the moored Liberty ships one by one from south to north. The Joseph Wheeler took a direct hit and burst into flames; moments later the John L. Motley, anchored next to the John Bascom, took a bomb on its number five hatch and the deck cargo on the ship caught fire. Heitmann saw the crew of the John L. Motley begin dousing the burning cargo with water from the fire hoses.

John L. Motley was struck by three bombs during the raid. Coxswain Thomas Edward Harper (1923–1995), a member of the Motley’s U.S.N.A.G. compliment who was on liberty during the raid, wrote in his report on the loss of the ship:

Inasmuch as the undersigned, and all surviving members of the crew were ashore, what occurred on board ship is not known, but an Armed Guard, who was on board the S.S. JOHN BASCOM during the attack, stated that [S.S. John L. Motley] sustained three bomb hits, one in number five hold, the second in number three hold, and the third went down the stack. He further stated that after number five hold was hit, fire broke out immediately, but was brought under control very shortly. Later, however when number three hold caught fire the crew was unable to extinguish it.

Despite her crew’s efforts, the fires eventually detonated John L. Motley’s volatile cargo, destroying the ship in a massive explosion. Most of the crew was killed, including Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class Davis. Soon after, Motley’s sister ship, S.S. John Harvey, also exploded. Many sailors were killed and hundreds injured by chemical exposure from Harvey’s cargo. In all, 17 ships were sunk. Total casualties to Allied sailors and Italian civilians are disputed, but very heavy.

At the time of the raid, a report indicates that John L. Motley’s crew 75 men: 46 merchant seamen and 29 U.S. Navy sailors. Approximately 38 merchant seamen and 24 sailors were killed or died of their wounds in the hospital. Contemporary casualty reports indicate that only about 13 men survived, none of whom had been aboard ship at the time of the raid.

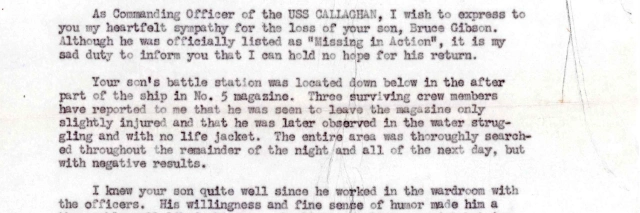

Journal-Every Evening reported that on January 26, 1944, that the Navy notified Davis’s family that he was missing in action. Under Public Law 490, Davis was declared dead a year and a day after his disappearance: December 3, 1944. In a letter to Davis’s parents dated December 15, 1944, an officer explained:

In view of the length of time that has elapsed without any indication that your son survived, and because of the strong presumption that he lost his life at the time of the explosion or shortly thereafter, I am reluctantly forced to the conclusion that he is deceased.

Journal-Every Evening announced on January 4, 1945, that “A memorial mass will be said at 8 o’clock next Monday morning [January 8, 1945,] at St. Patrick’s Church” for Davis.

Remarkably, there was an unexpected silver lining to the Bari tragedy, as Jennet Conant wrote in her book, The Great Secret: The Classified World War II Disaster That Launched the War on Cancer. Various researchers during preceding decades had identified mustard gas as a potential therapeutic agent against cancer. A team at Yale had even run a small, mostly unsuccessful clinical trial treating terminal cancer patients with a nitrogen mustard compound during 1942 and 1943. A report by Lieutenant Colonel Stewart F. Alexander (1914–1991) on the clinical effects of the mustard gas on the Bari disaster’s victims, such as decreased white blood cell count, put the toxin’s potential “back under a microscope and grabbed the medical community’s attention.” In turn, this was instrumental in the development of the first chemotherapy drugs shortly after the war.

Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class Davis is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Date Davis Joined S.S. John L. Motley

Davis’s personnel file stated that the dates he was discharged from the hospital and joined S.S. John L. Motley were unknown. Some paperwork was lost with the ship and duplicate paperwork had not yet been submitted to the Bureau of Naval Personnel when the tragedy occurred. Presumably, the hospital discharge occurred no sooner than November 12, 1943, when his previous ship, S.S. Thomas Hart Benton, sailed from Oran, and no later than November 20, 1943, when John L. Motley departed that port.

S.S. John L. Motley Casualties

Neither Infield and Conant were clear about whether any men survived the explosion of the John L. Motley other than those already ashore. Infield stated that all men on board were killed, but also included a casualty report stating that there were 75 men aboard “at time of action” with 64 casualties. It seems possible that the person filling the report out had erroneously included those men ashore, but Infield did not comment on the discrepancy. In the appendix, a casualty report dated December 12, 1943, stated that among the Motley’s crew and U.S. Navy Armed Guard compliment, there were 19 survivors, with another 8 men dead and 45 missing.

Conant stated that 64 men were killed and the only survivors were 11 men ashore. However, she also stated that according to Lieutenant Colonel Alexander’s investigation, 18 men aboard the Motley were killed by mustard exposure, something that would seem to be unlikely given that Motley exploded before Harvey did.

With regard to Motley’s U.S. Navy compliment, a casualty report compiled shortly after the disaster stated that that there were 29 men assigned at the time of the raid. Of those, eight died in the hospital, 16 were missing, and only five survived, all of them ashore. A War Shipping Administration casualty count accompanying a December 29, 1943, letter gave similar figures for Motley’s Navy compliment: eight dead, 17 missing, and four survivors—suggesting that one sailor hadn’t been accounted for by that time. The same source stated that among Motley’s merchant seamen, there were 16 dead, 22 missing, and eight survivors.

Bibliography

Certificate of Birth for Leslie Joseph Davis. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-D4FS-46S

Certificate of Birth for Thomas Davis. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D14Q-B7Z

Conant, Jennet. The Great Secret: The Classified World War II Disaster That Launched the War on Cancer. W. W Norton & Company, 2020.

“Convoy AH.10.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ah/index.html?ah.php?convoy=10!~ahmain

“Convoy KMS.32.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/kms/index.html?kms.php?convoy=32!~kmsmain

Davis, Leslie. Thomas Charles Davis Individual Military Service Record, August 22, 1945. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18335/rec/7

“Deck Log Book U.S.S. PREBLE Month of June, 1943.” World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/134255664?objectPage=24

“Divulge Names of Six Men of 59th Pioneers Killed By Mine Blast.” The Evening Journal, April 3, 1919. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-evening-journal-thomas-joseph-davis/147739719/

Draft Registration Card for Thomas Charles Davis. February 16, 1942. WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_01_00002-00812

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531892_00944

Infield, Glenn B. Disaster at Bari. The Macmillan Company, 1971.

“John L. Motley.” Armed Guard Files, 1940–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Leslie Davis.” Journal-Every Evening, September 1, 1986. https://www.newspapers.com/article/147762057/

“Margaret Mary Zickgraf Davis.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/107114826/margaret-mary-davis

“Naval Armed Guard at Bari, Italy.” Naval History and Heritage Command website. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/naval-armed-guard-service-in-world-war-ii/naval-armed-guard-at-bari-italy.html

“Navy Reports Seaman Lost.” Journal-Every Evening, January 29, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/147742451/

Official Military Personnel File for Thomas C. Davis. Official Military Personnel Files, 1885–1998. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Sailor, Missing Year, Is Now Presumed Dead.” Journal-Every Evening, December 23, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/147742155/

“Ship Movements: JOHN L MOTLEY (Amer) 7,176 tons, built 1943.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ports/index.html?search.php?vessel=JOHN%20L%20MOTLEY~armain

“Ship Movements: STANVAC MANILA (Pan) 10,169 tons, built 1941.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. https://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ports/index.html?search.php?vessel=STANVAC%20L%20MANILA~armain

“Ship Movements: THOMAS HART BENTON (Amer) 7,187 tons, built 1943.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. https://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ports/index.html?search.php?vessel=THOMAS%20HART%20BENTON~armain

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00551-00702

“Thomas C. Davis.” Journal-Every Evening, January 4, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/147742234/

Visser, Auke. “Stanvac Manila (I) – (1941-1943).” Auke Visser’s Other Esso Related Tankers Site. http://www.aukevisser.nl/others/id396.htm

Last updated on May 20, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.