| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Harrington, Delaware | Recent graduate |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 42145866 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “C,” 17th Armored Infantry Battalion, 12th Armored Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 504 (ammunition handler) | Colmar Pocket (Rhineland campaign) |

Early Life & Family

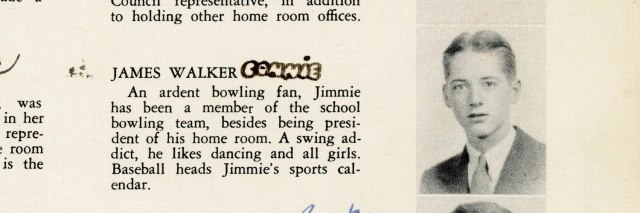

Robert Martin Tee was born in Harrington, Delaware, on the afternoon of March 11, 1926. He was the second child of Albert Tee (an electrician, 1897–1971) and Sara Emo Tee (née Sara Emo Farrow, 1899–1978). He had an older sister, Ruth Alberta Tee (1921–2005). He was Protestant.

Tee was recorded on the census on April 2, 1930, living with his parents, sister, and paternal grandfather in Harrington. Census records indicate that the family moved from Kent to Sussex County by April 1, 1935. At the time of the census taken in April 1940, Tee was living with his parents and sister at 223 8th Street in Laurel, Delaware.

By the time Tee registered for the draft on his 18th birthday, March 11, 1944, he had returned to Harrington. He was living with his family on Grant Street, attending high school, and working for Harrington & Raughley. The registrar described him as standing five feet, 10½ inches tall and weighing 153 lbs., with black hair and brown eyes.

Tee’s enlistment data card stated that he had completed three years of high school. On the other hand, the Wilmington Morning News reported that Tee had graduated from Harrington High School in June 1944. Similarly, his mother’s statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission stated that Tee had “Just graduated from High School” when he was drafted.

Military Training

According to his mother’s statement, Tee “Tried to enlist in Navy also Air Corps[.] Turned down.” Most voluntary enlistments had ended by executive order at the end of 1942, although there were exceptions for 17-year-olds and men over 37. It is unclear if Tee tried to enlist at 17 and was turned away or whether, after he was drafted at 18, he requested naval service, which would have made him—had he been accepted—a “selective volunteer” in U.S. Navy parlance.

Tee joined the U.S. Army at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on June 23, 1944. After a short period at the reception center there, he attended basic training at the Field Artillery Replacement Training Center, Fort Bragg, North Carolina. A note in Tee’s mother’s statement indicates he was with the 4th Field Artillery Training Regiment there. She wrote that he had 17 weeks of training at Fort Bragg from July to November 1944, then received a 10-day furlough. His mother recalled in a letter six months later:

We trained him 18 years how to live a clean, honest, life and to have tolerance and respect of his fellow men. He was liked by every one who knew him. He did want to come back so, ever so bad. The last time we put him on the train, he told us he didn’t want to have to kill.

Tee’s mother wrote that her son reported to the Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, on November 20, 1944. She added that Private Tee shipped out from the Boston Port of Embarkation on December 22, 1944, disembarking in Scotland soon after.

According to the statement, Tee soon moved to England and then France, where he was assigned to Company “C,” 17th Armored Infantry Battalion, 12th Armored Division. A company morning report stated that Private Tee was one of five replacements who was assigned to and joined the unit in the Alsace region of France, transferring in from the 3rd Replacement Battalion on January 25, 1945.

The 12th Armored Division had been activated on September 15, 1942. On November 11, 1943, the division’s 56th Armored Infantry Regiment was broken up and 2nd Battalion reorganized into the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion. The unit went overseas in September 1944 and entered combat in eastern France in early December 1944.

In late 1944, the Germans had launched two major offensives on the Western Front. The first, focused on the Ardennes, began December 16, 1944, resulting in the well-known Battle of the Bulge. On December 31, 1944, another offensive began further south: Operation Nordwind. In mid-January 1945, the 12th Armored Division took heavy casualties near Herrlisheim, France, during fighting in connection with the Northwind offensive. During the month of January 1945, the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion sustained casualties of at least 17 men killed, 114 men wounded, and 166 men missing or captured. Private Tee was among the replacements for these casualties.

Details in an emotional letter from his mother to President Truman written later that spring suggests that Private Tee’s military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) was initially 641, field lineman or wireman and telephone operator. Furious about what the apparent irrationality of the Army’s personnel decisions, she wrote:

Our only boy and baby Pvt. Robert M. Tee, had 17 weeks training in the Field Artillery setting up switch boards and stringing wire for command post telephones. His last letter written us Jan 28, 1945, told us he had been put in the infantry on Jan 26th, and sent direct to the front, without any infantry training. And was very much afraid and discouraged. The reason the hurt is so deep, they didn’t need him in his trained position. But did take one of his buddies (a cook) and trained him for our boy’s job at the same time of our boy’s transfer – We didn’t think America would do this to their youths– Especially when there are boys still going from camp to camp after being in the service two and three years.

Even at a Field Artillery Replacement Training Center, Private Tee’s basic training would have included some infantry skills. In combat, infantry units typically took the highest casualties, and serving as an armored infantryman was especially hazardous. It was not uncommon for men from the Field Artillery or other branches to be transferred to infantry units. In some cases, they first received infantry refresher training, though based on Tee’s mother’s letter, he did not. The Company “C” morning report listed Private Tee’s M.O.S. code as 504, ammunition handler, a job he could have performed without extensive retraining on an unfamiliar weapon.

Although tanks were the offensive core of armored divisions, there were many situations where mission or terrain required infantry support. Armored infantrymen were typically transported by halftrack, giving them the mobility to keep up with the tanks during breakthroughs. During World War II neither armored infantrymen nor conventional infantrymen were issued body armor. Their vehicles provided little protection against enemy fire and armored infantrymen typically fought dismounted.

According to unit records, on January 25, 1945, the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion moved from Keinheim to Breuschwickersheim, France, “where it carried on re-organization and a training schedule for the new reinforcements assigned to the battalion until the end of the month.”

First, Final Battle

The 17th Armored Infantry Battalion’s next mission involved the reduction of the Colmar Pocket, a salient of German-held territory on the west bank of the Rhine in Alsace. On February 2, 1945, the unit moved to Houssen, France. According to the battalion after action report, on February 3, 1944:

At 2030 the Battalion moved out to the south and closed in the south edge of COLMAR at 2300. […] At this time the plan was for the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion to take over three small towns from the French First Army southwest of COLMAR (WETTOLSHEIM, EGUISHEIM, and [Husseren]); to attack south at daylight in conjunction with CC-B [Combat Command “B”] and to protect the west flank of the 12th Armored Division.

The relief of the French Forces was accomplished without incident prior to daylight, February 4. At 0930 C Company with one platoon of Medium Tanks attached, moved out to attack VOEGTLINSHOFFEN. The attack proceeded very slowly and was held up by small arms and mortar fire.

A company history published shortly after the war, entitled Mount Up!, described the attack in further detail:

The civilians stood around watching us file out with tanks rumbling in the midst of us. The first and third platoons led off, then the second and the A/T [antitank]. While the first platoon swung off the road to the high ground on the right, using wire cutters to get through an [sic] vineyard, the third platoon went into a field on the left. Artillery fell in the third platoon area; it was our own and before the FO [forward observer] could get word back by radio to cease fire several men had been hit. That was a blow but the attack continued. The platoon got into the town with a tank but were held up after their initial penetration. Meantime the second platoon had come down the road and was crossing the large vineyard directly in front of town, following an [sic] tank which knocked a path through the wires. After the rifle squads were in town except for one or two men, a burp-gunner [submachine gunner] opened up on the mortar squad which was still tangled in the vineyard. [Private 1st Class Robert J.] Crandall was killed instantly, then two more men were wounded. The other men tried to reach a house on their right which would provide cover, but [Private 1st Class Hollis J.] Gunyon and Tee were killed before they could get out of the burp gun sights.

That afternoon, orders came from Combat Command “R,” 12th Armored Division, directing the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion to “Break contact immediately” and assemble at Eguisheim for another advance south with the 23rd Tank Battalion. The battalion after action report stated:

C Company was closely engaged with the enemy and had secured about two-thirds of their objective when this order came down. This difficult operation of disengaging from a fire fight in daylight was accomplished with very minor losses as the enemy did not elect to pursue our force.

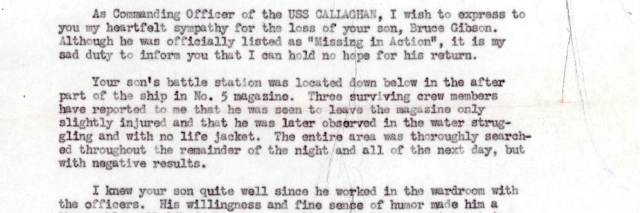

Private Tee was killed during his first day in combat, February 4, 1945. Although his death near Voegtlinshoffen had been witnessed, Tee’s body was left behind when his company withdrew. For that reason, Private Tee’s was initially classified as missing in action, a status duly reported by the Wilmington newspapers on February 27, 1945.

Private Tee was initially buried in an isolated grave southwest of Voegtlinshoffen (approximate position 48° 0’ 23” North 7° 16’ 0” East), presumably by either the Germans or by French civilians. On April 3, 1945, he was reburied at the U.S. Military Cemetery, Epinal, France. Tee was identified by his dog tags and laundry marks on his clothing. Contrary to the account in Mount Up!, according to Tee’s burial report, he was struck by a shell fragment on the left side of his head and killed. It was only on May 7, 1945, that the War Department changed his status to killed in action.

The following day, May 8, 1945, Victory in Europe Day, was a day of celebration for millions of Americans and their allies. For the Tee family, however, it was a day of tragedy, when they received a telegram that extinguished their hopes that Private Tee would return alive. Two days later, Tee’s mother sat down and composed a long letter to President Truman. She told him about her son, her fury about him being thrown into combat without more infantry training, and to beg him to make an exception to the timetable of disposition of war dead and bring her son’s body home immediately. She wrote in part:

One hour and a half after you proclaimed V.E. Day, we received a telegram from the War Department, that our boy previously reported missing Feb 4, 1945 was killed in action Feb 4, 1945, in France. As he was only 18 and our most prized possession in the world, only God in Heaven will ever know how torn our minds and bodies are, after we had prayed and prayed that he might be a prisoner and return to us some day.

The White House forwarded the letter to the Quartermaster Corps, which advised her that repatriation of war dead would be started shortly at government expense, though in the event, that process did not begin until 1947.

The Wilmington Morning News reported that on Memorial Day 1945, “The Rev. Thomas C. Jones of Trinity Methodist Church in a Union service, delivered the Memorial Day sermon. The flowers on the alter were in memory of Private Robert M. Tee and Grant Perry.” The article added that at a memorial service planned for Hollywood Cemetery on May 30, 1945, “Gold certificates will be presented to the family of deceased veterans” including Tee’s.

More frustration was in store for the Tee family. No personal effects had been returned to his family by November 12, 1945, and there is no indication in his individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) that any were ever recovered.

Tee’s mother wrote to the Delaware archivist, Leon deValinger Jr. (1905–2000), in a letter dated December 18, 1946: “Just this week I received a letter from the Priest of the village where my son met death. […] On Feb 4th every year they have some kind of service in memory of the three American boys that gave their lives. My son and the other two.”

When finally given the opportunity to decide the disposition of their son’s remains after the war, Tee’s family again requested that his body be repatriated to the United States. Tee’s father asked if Homer Hensel (likely 1917–1988) of Detroit, Michigan, could “serve as an escort for my son since he was in his squad and together [when/where] my son was killed” but the War Department was unable to honor that request. Private Tee’s body returned to the United States aboard the Liberty ship Robert F. Burns from Antwerp, Belgium, to the New York Port of Embarkation.

On April 8, 1948, Journal-Every Evening reported that Private Tee’s body was due to arrive in Harrington the following afternoon. The article added:

A delegation from Calloway-Kemp-Raughley-Tee Post, American Legion, will escort the body to the Boyer Funeral Home, where services will be held Sunday [April 11] at 2 p. m. in charge of the Rev. J. Harry Wright of Asbury Methodist Church assisted by a former pastor, the Rev. Robert E. Green of Smyrna.

Private Tee is one of four veterans of this city for whom the American Legion post was named and his body is the first of the group to be returned.

The pallbearers will be William Jester, Jr., Harold Melvin, Gayle Smith, Clyde Tucker of Harrington and David Herson, Milford; George Swain, Jr., Georgetown; all veterans of World War II.

Private Tee was buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Harrington. His parents were buried alongside him after their deaths.

Notes

M.O.S. 504

Tee’s M.O.S. code, 504 (ammunition handler), was supposedly an obsolete code by 1944. The similar duty of ammunition bearer was retained, but those in an armored infantry rifle company were supposed to have been recoded based on their assignment. After the change, all members of those shared the same M.O.S. code. So, whether squad leader, gunner, or ammunition bearer, a man’s M.O.S. code was determined by whether he was a member of a light machine gun squad (604), mortar squad (607), or antitank squad (610). Still, despite the changes in M.O.S. codes and tables of organization implemented during the last few years of World War II, supposedly obsolete M.O.S. codes like 504 and 653 (squad leader) consistently appear in U.S. Army morning reports from many different units through the end of the war.

Cause of Death

The discrepancy in cause of death between the burial report and Mount Up! raises the possibility that Tee was actually killed by fire from friendly artillery rather than enemy submachine gun fire. Potentially, the account of his death could have sanitized in a postwar account intended as a memento for the soldiers of Tee’s unit and their families. Indeed, Tee’s family obtained a copy of Mount Up! in 1946 and they surely would have been upset if his death had been reported as friendly fire. Of course, it is entirely possible that when his body was exhumed two months after his death that graves registration personnel filling out paperwork mistook shell fragment wounds for gunshot wounds. A submachine gun round would have been less likely to leave an exit wound than a higher-powered rifle or machine gun round.

Curiously, the headstone of Private 1st Class Hollis J. Gunyon (1925–1945), who Mount Up! stated was killed at the same time as Private Tee, lists his date of death as the following day, February 5, 1945. The other man killed, Private 1st Class Robert J. Crandall (1910–1945), does have the February 4 date of death on his headstone.

Full Text of Mother’s Letter

May 10, 1945

Dear President Truman:–

One hour and a half after you proclaimed V.E. Day, we received a telegram from the War Department, that our boy previously reported missing Feb 4, 1945 was killed in action Feb 4, 1945, in France. As he was only 18 and our most prized possession in the world, only God in Heaven will ever know how torn our minds and bodies are, after we had prayed and prayed that he might be a prisoner and return to us some day.

To have our hopes and his shattered to pieces this way[.] We trained him 18 years how to live a clean, honest, life and to have tolerance and respect of his fellow men. He was liked by every one who knew him. He did want to come back so, ever so bad. The last time we put him on the train, he told us he didn’t want to have to kill. If he did, we hope and pray that the heavenly father will have mercy on his soul. He had a [unclear, possibly horror] of the infantry. Our only boy and baby Pvt. Robert M. Tee, had 17 weeks training in the Field Artillery setting up switch boards and stringing wire for command post telephones. His last letter written us Jan 28, 1945, told us he had been put in the infantry on Jan 26th, and sent direct to the front, without any infantry training. And was very much afraid and discouraged. The reason the hurt is so deep, they didn’t need him in his trained position. But did take one of his buddies (a cook) and trained him for our boy’s job at the same time of our boy’s transfer – We didn’t think America would do this to their youths– Especially when there are boys still going from camp to camp after being in the service two and three years.

We have helped the government in every way[,] bought bonds until it hurts, helped the red cross generously also U.S.O. and bundles for stricken allies – There is only one request we would like to make, we know it is an exception. We would like for you to see that there is a small niche on any ship that returns to these shores, for his body. Please have his body put in a metal casket. If the government feels they can’t bear the expense, we will. The war department used our baby and prized possession as an exception.

But please, please return him to us soon with one of the boys that was in his squad or battalion that knew him– As a guard of honor– May god Almighty the Heavenly Father be with you and guide your thoughts when you make this decision.

Once again our hearts and souls cry out that you will find a small niche on any ship and return our baby to us very, very soon[.]

We trust and pray with the help of God that our last and only request be granted to us. And may God guide you through your task ahead.

We are,

Heart broken folks.

Mr. & Mrs Albert Tee

Pvt. Robert M Tee 42145866

Co C. 17 A.I.

A.P.O. 262. c/o P/M N.Y.

Under the 12th Armored Division of the 7th Army.

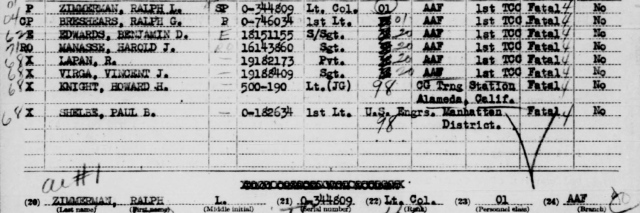

New York Casualty List

Due to an error, the official 1946 U.S. Army casualty list has a duplicate of Private Tee. He is included correctly on the list for Kent County, Delaware, and erroneously on the list for Queens County, New York.

Acknowledgments

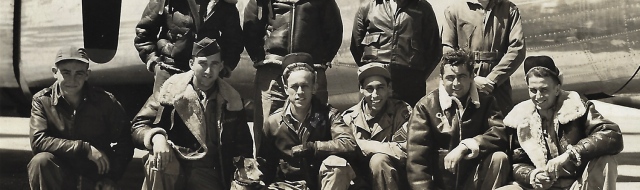

Special thanks to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for providing morning reports that established the date that Private Tee joined his final unit as well as his final M.O.S. Thanks also go out to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“3 From State Die in Action; 3 Wounded.” Wilmington Morning News, February 27, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136420060/

“Albert Tee.” The Morning News, March 8, 1971. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-morning-news-albert-tee-obit/136418354/

“Attack Order.” Headquarters 17th Armored Infantry Battalion, February 4, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Certificate of Birth for Robert Martin Tee. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQM-Q7MB

Draft Registration Card for Robert Martin Tee. WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_04_00008-01440

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531890_00343

“Four Missing Delaware Men Died in Action.” Journal-Every Evening, February 27, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136419423/

“Harrington Man Killed in Action.” Wilmington Morning News, May 9, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136420354/

“Harrington Plans Honors for Hero.” Journal-Every Evening, April 8, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136419082/

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Robert M. Tee. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

“Memorial Program Held in Harrington.” Wilmington Morning News, May 29, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136419987/

Morning report for Company “C,” 17th Armored Infantry Battalion. January 26, 1945. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

Mount Up!: The History of Company C 17th Armored Infantry Battalion 12th Armored Division. W.A. Seierlin, 1945

Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897–1957. Record Group 85, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7488/images/NYT715_7018-0233

S-3 Journal for 17th Armored Infantry Battalion, February 4, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00547-00595

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

“Table of Organization and Equipment No. 7-27: Rifle Company, Armored Infantry Battalion.” War Department, September 15, 1943. Military Research Service website. https://www.militaryresearch.org/7-27%2015Sep43.pdf

Tee, Sara Emo. Individual Military Service Record for Philip Alden Beaman. March 30, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/21552/rec/1

“Unit History February 1 – February 28, 1945.” Headquarters 17th Armored Infantry Battalion. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=42145866&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=8352952

Last updated on April 5, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.