| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Ohio, Delaware | Factory worker |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32481369 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Battery “C,” 969th Field Artillery Battalion |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 641 (field lineman or wireman and telephone operator) | Normandy campaign, Battle of Brest, Rhineland campaign, Battle of the Bulge |

Early Life & Family

John James Mills was born in Columbus, Ohio, on November 14, 1920. He was the son of Phillip Thomas Mills (c. 1871–?) and Lelia Mills (née Saunders, 1886–1939). His father, a clergyman, was born in the West Indies (Cuba according to census records and Sint Eustatius according to marriage records), while his mother was from Virginia. They married in Wilmington, Delaware, on November 14, 1908, and according to census records, subsequently lived in New York before moving to Ohio.

Mills had at least three older brothers (two of whom apparently died young), and a younger brother. The Mills family was recorded on the census on April 4, 1930, living at 1074 Leonard Place in Columbus. Mills’s father was recorded as a laborer in a railroad shop. The family was still living there when the 1934 Columbus city directory was printed. The elder Mills was listed as a pastor at Church of God and Saints of Christ. Leila Mills died in Columbus on September 9, 1939.

Journal-Every Evening stated that Mills moved from Youngstown, Ohio, to Delaware around 1941. He was a resident of Wilmington by September 8, 1941, when he was listed as a witness when his father remarried to Margaret Moon in Wilmington.

According to his father’s statement to the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission, Mills was a factory worker. When he registered for the draft on February 16, 1942, Mills was living with his father at 1010 Bennett Street in Wilmington and working for the Delaware Tool Corporation at 3300 Market Street. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, six inches tall and weighing 170 lbs., with black hair and eyes, and a scar on his forehead. He was Protestant according to his dog tags.

Journal-Every Evening reported on February 3, 1945, that “A brother, Leslie Mills, seaman in the Navy, is serving in the Pacific. His step-sister, Sergt. Dorcas Moon, is in the WAC.”

Military Training & Journey Overseas

Mills was drafted by Wilmington Local Board No. 2 and entered the U.S. Army on November 19, 1942, most likely at Camden, New Jersey. His father’s statement indicated that Mills was briefly stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and then in Oklahoma. Curiously, Journal-Every Evening did not mention any service in Oklahoma, reporting that Mills “received training at Fort Devens, Mass., and Camp VanDorn, Miss.” and indicated that he went overseas around January 1944. Private Mills’s only known unit was Battery “C,” 969th Field Artillery Battalion, a segregated unit with black enlisted men and white officers. Although it is unclear when Mills joined the battalion, a scrap of paper in the Delaware Public Archives with his name, unit, and return address care of the postmaster in Shreveport, Louisiana, suggests that he was already with the unit by the fall of 1943.

Mills’s battalion had originally been activated at Camp Gruber, Oklahoma, on August 5, 1942, as 2nd Battalion, 333rd Field Artillery Regiment. On March 22, 1943, the regiment was reorganized into the 333rd Field Artillery Group and several separate battalions, with 2nd Battalion redesignated as the 969th Field Artillery Battalion. The battalion moved to Louisiana for maneuvers in mid-September 1943, and later moved to Jasper, Texas, before returning to Camp Gruber in mid-November. The unit was equipped with towed 155 mm howitzers.

On February 3, 1944, the 969th arrived at Camp Shanks, New York, a staging area for the New York Port of Embarkation. The following month, on March 1, 1944, the battalion sailed for the United Kingdom aboard the ocean liner-turned troop transport R.M.S. Queen Mary. The unit arrived in Scotland on March 7, 1944, and the following day reached Crewe, Cheshire, England. The unit was based at a 17th century mansion, Crewe Hall. The unit journal reported that the battalion had adopted the Crewe family motto, “Sequor Nec Inferior,” which the journal translated as “never behind.” (Another translation, which could be taken as sly reference to the battalion’s place in the segregated U.S. Army, is “I follow, but I am not inferior.”)

According to a battery morning report, Private Mills’s Military Occupational Specialty (M.O.S.) was 641, field lineman. Within the context of the tables of organization of a towed 155 mm battery, a private with an M.O.S. of 641 had the title of wireman and telephone operator. Communications, both via radio and wire, were vital to artillery units. Forward observers in an observation post or light aircraft would provide target information to men in the Fire Direction Center (F.D.C.), who would perform calculations and relay firing instructions to the cannoneers and gunners manning the guns themselves.

Combat in the European Theater

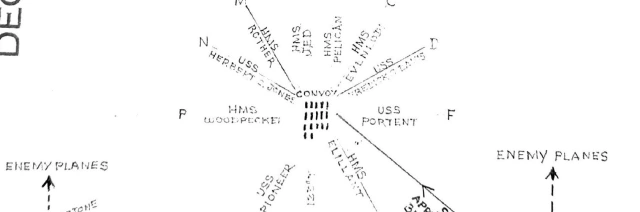

On June 21, 1944, about three weeks after D-Day, the 969th Field Artillery Battalion moved to a concentration area at Camp Chipping Norton in Oxford, England, and then a marshalling area at Dorchester on July 4. The battalion boarded L.S.T.s and L.C.T.s at Portland Harbour on the morning of July 8, 1944, and sailed for France that night. The unit began disembarking at Utah Beach on the afternoon of July 9, 1944, and was initially assigned to support the 8th Infantry Division. The battalion fired its first shots in anger near La Haye-du-Puits late on July 10, 1944. As the Normandy campaign drew to a close, the battalion was involved in the Allied advance west into Brittany. The battalion was attached to the 4th Armored Division from August 5–14, 1944. Later that month, the 969th supported the 2nd Infantry Division during the Battle of Brest. After the surrender of the German garrison, the unit headed east to the front on September 28, 1944.

The battalion journal reported that the 969th first fired into Germany on October 4, 1944. The rapid drive across France during the summer of 1944 had given way to near stalemate at the German border that fall. The battalion spent the next two months supporting actions aimed at piercing the German Westwall, known as the Siegfried Line to the Americans.

By the beginning of December 1944, the 969th Field Artillery Battalion was attached to the 174th Field Artillery Group in a quiet sector near the borders of Belgium and Luxembourg. That changed on December 16, 1944, when the Germans launched a counteroffensive through the Ardennes Forest that came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge. The 969th was in the thick of the fighting, initially in support of the 28th and 106th Infantry Divisions. The German advance threatened to overrun the battalion, which began to withdraw on the third day of the battle.

On December 19, 1944, the 969th was attached to the 333rd Field Artillery Group. The battalion would assist elements of the 101st Airborne and 10th Armored Divisions during the upcoming defense of Bastogne, Belgium. Enemy armor could not easily travel cross-country in the area. For the Germans’ offensive to continue unimpeded, they would have to capture the small crossroads town. The 333rd Field Artillery Group’s other two battalions had been badly mauled during the opening days of the German offensive. The survivors of the white 771st Field Artillery Battalion retreated without their guns. The 333rd Field Artillery Battalion, another black unit, had just two serviceable guns following their retreat, which were attached to Battery “A,” 969th Field Artillery Battalion. (Among the atrocities perpetrated by German forces during the Battle of the Bulge, several men from the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion, later known as the Wereth 11, were captured and brutally executed on December 17, 1944.)

On December 20, 1944, the 969th took up positions southwest of Bastogne near Villeroux. The Americans repulsed two attacks in the area of Villeroux on December 21, 1944. The Germans were close enough that the 969th suffered casualties from mortar and small arms fire, and the battalion pulled back to Senochamps that afternoon. Most of the battalion withdrew again to the vicinity of Bastogne itself on the afternoon of Christmas Eve, losing several men when German aircraft bombed the town that night.

The 969th’s after action report stated:

From the night of 21 December, 1944 until the night of 27 December , 1944 the Battalion was surrounded. As ammunition was short, all missions fired were observed. In order to cover all sections of the perimeter, Batteries were layed in platoons, even then it was often necessary to shift trails to cover missions.

In plain language, to conserve ammunition, the battalion fired only under the direction of observers rather than unobserved fires based only on map coordinates requested by one of the units the 969th was supporting. Usually, an entire battery of four 155 mm howitzers were positioned parallel so they could be concentrated on a single target area, but there was not enough artillery to cover the perimeter that way. Furthermore, the 969th still sometimes had to “shift trails”: that is, turn their guns (trails being the structures by which the howitzers were towed and which stabilized the gun in its firing position, extending in a V shape behind the gun). Shifting trails greatly increased the artillerymen’s workload, both because the guns had to be manhandled into the new positions and because doing so disrupted their aim.

During the siege, the 969th worked closely with the 420th Armored Field Artillery Battalion of the 10th Armored Division. According to the battalion after action report, after a nearby armored unit began running out of gasoline on Christmas, members of the 969th drained fuel from their own vehicles to keep the armor in action. That same day, Battery “C” responded to “an urgent fire mission” against an enemy position that included a six gun artillery battery, which they reportedly knocked out.

Although food and gasoline started arriving by air on December 23 or 24, 1944, the after action report stated that it wasn’t until the morning of December 27, 1944, when the battalion received its first ammunition resupply of the siege: 155 mm shells arrived via glider. The U.S. Third Army broke through to Bastogne that same day. Service Battery of the 969th Field Artillery Battalion followed, bringing supplies with them. Despite the relief of the siege, fierce fighting continued in the area.

The 969th Field Artillery Battalion after action report for the month claimed seven tanks, six light guns, and 12 other vehicles destroyed. The reported added that 10 tanks and 20 other vehicles were “probably damaged or destroyed” and that “The Battalion personally takes credit for breaking up at least six enemy counter-attacks with artillery fire alone.” Battalion casualties for the month of December 1944 were seven dead, 12 wounded, and three missing, plus one dead officer attached from the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion.

On December 28, 1944, the 969th Field Artillery Battalion was attached directly to the 101st Airborne Division. Even with the German siege broken, the 969th was involved in supporting actions to retake the area surrounding Bastogne. On January 12, 1945, the battalion was attached back to the 333rd Field Artillery Group in support of the 11th Armored Division’s drive northeast to Houffalize, Belgium.

As of January 14, 1945, Private Mills’s battery was stationed in or near the village of Recogne, northeast of Bastogne in the vicinity of Foy, Belgium. Private Mills was killed in action that day. The battalion journal recorded the following entry at 0915 hours:

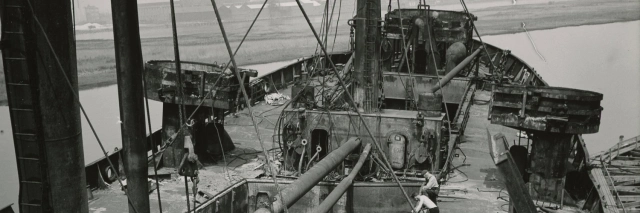

A bomb was accidentally dropped in “C” Battery area and the [following] enlisted men were killed or wounded: 1st/Sgt Jon C. Hall and Sgt. James Keith were killed, and Pvt. John G. [sic] Mills. The wounded were Cpl. Albert Price and T/5 Meredith Trent. One 4-ton truck destroyed and 2 vehicles slightly damaged by fragments.

The journal added that at 1050 hours, “Lt. Col. Florer, Exec[utive Officer of the] 333rd. F.A. Gp., arrived to investigate above mentioned bombing[.]”

The 333rd Field Artillery Group’s S-2 journal provided further detail about the incident. The evidence suggests that the bomb was dropped by an American fighter-bomber, a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. It was unclear if the release was due to mechanical failure or pilot error, but was clearly not the result of an intentional attack:

1 4 ton prime mover – destroyed: 1 2½ ton truck – radiator damaged: 1 3/4 ton truck – top blown off: 3 men killed: 2 men injured. 8 P 47’s over area at the time. No squadron markings observed. 1 bomb dropped. Plane circled area afterwards – vic[inity] Bastogne[.]

According to his report of burial, Private Mills died from serious wounds to his abdomen and both legs. He was buried on January 18, 1945, at the U.S. Military Cemetery No. 1 at Grand Failly, France.

On January 3, 1945, Major General Maxwell D. Taylor wrote a letter of commendation to the commander of the 969th Field Artillery Battalion, which reached the battalion the night after Private Mills was killed. The letter read in part:

The Officers and Men of the 101st Airborne Division wish to express to your command their appreciation of the gallant support rendered by the 969th Field Artillery Battalion in the recent defense of Bastogne, Belgium. The success of this defense is attributable to the shoulder to shoulder cooperation of all units involved. This Division is proud to have shared the Battlefield with your command. A recommendation for a unit citation of 969th Field Artillery Battalion is being forwarded by this Headquarters.

That recommendation was indeed acted upon and on February 7, 1945, under the authority of Lieutenant General George S. Patton, the 969th was awarded a unit citation per General Orders No. 31, Headquarters Third United States Army.

The effects recovered from Private Mills’s body included a well-worn brown leather billfold and a Judex wristwatch (both apparently damaged in the explosion that claimed his life). Six photographs and a Social Security card, all stained by blood, were also found. The Quartermaster Corps wrote his father to ask if he wanted the effects forwarded, explaining: “It is our desire to refrain from sending any article which would be distressing; at the same time, we do not feel justified in removing them without your consent.” Mills’s father wrote back on July 23, 1945, requesting that all his son’s property be shipped to him.

In 1947, Mills’s father requested that his son be buried in a permanent military cemetery abroad. Private Mills’s body was disinterred from Grand Failly on August 5, 1948. On January 21, 1949, Private Mills was reburied at the U.S. Military Cemetery Hamm (now known as the Luxembourg American Cemetery) in Plot E, Row 8, Grave 20.

Notes

Date of Birth

Although the Adjutant General’s Office report of death for Private Mills listed his date of birth as November 14, 1921, his birth certificate and draft card listed November 14, 1920.

Middle Name

Curiously, although both his draft card and father’s statement list his name as John James Mills, his dog tags listed his name as John H. Mills.

Induction Location

Private Mills’s enlistment data card was among those that were lost or could not be digitized successfully. In some cases, searching for sequential service numbers around the missing card can at least reveal the date and location of induction. Many of the other cards around his (32481369) also appear lost or garbled. One, 32481375, though having a garbled name, was digitized as belonging to a man inducted at Camden, New Jersey, on November 19, 1942. Another, 32481377, also had a garbled name but the same location and a similar date, November 10, 1942.

It is very likely that both men were inducted on the same date, but that the card was poorly microfilmed, resulting in the introduction of some errors when the card was digitized. The Adjutant General’s Office report of death for Private Mills listed his entry into the Army as November 19, 1942. Many draftees from Delaware were inducted in Camden, so it is likely that Mills was as well.

Armored Unit at Bastogne

The 969th’s after action report did not identify the armored unit that it supplied with fuel on Christmas 1944 beyond to describe them as tanks. These may have been a platoon of M4 medium tanks from Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division, or M18s from the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion, since tank destroyers were often casually referred to as tanks.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Emily Vaill Pfaff and the Barnes family, as well as to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photos. Thanks also go out to Dennis Victor Dupras for his assistance in explaining the battalion after action report in plain language and to Thulaï van Maanen for her assistance examining the mystery of which armored unit the 969th supplied fuel to during the siege of Bastogne.

Bibliography

333rd Field Artillery Group S-2 journal. January 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

969th Field Artillery Battalion journal. July 1944 – January 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Barnes, Hubert D. “Action Against Enemy, Reports After/After Action Report for the month of August, 1944.” Headquarters 969th Field Artillery Battalion, September 4, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Barnes, Hubert D. “Action Against Enemy, Reports After/After Action Report for the month of December, 1944.” Headquarters 969th Field Artillery Battalion, January 6, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Barnes, Hubert D. “Action Against Enemy, Reports After/After Action Report for the month of January 1945.” Headquarters 969th Field Artillery Battalion, February 14, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Barnes, Hubert D. “Action Against Enemy, Reports After/After Action Report for the month of September, 1944.” Headquarters 969th Field Artillery Battalion, October 9, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Barnes, Hubert D. “Action Against Enemy, Reports After/After Action Reports. (Month of July/44.)” Headquarters 969th Field Artillery Battalion, August 15, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Delaware Flier, GI Give Lives; Three Injured.” Journal-Every Evening, February 3, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/103080393/mills-kia-1/, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/103080444/mills-kia-2/

Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1673/images/31297_212339-00312, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61368/images/TH-267-12375-87837-89

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4638935_00581

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4384863_00166

John J. Mills Individual Deceased Personnel File. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

“Lelia Saunders Mills.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86811908/lelia-mills

Mills, Phillip T. John James Mills Individual Military Service Record, c. 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20019/rec/1

Morning report for Battery “B,” 969th Field Artillery Battalion, January 15, 1945. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri.

Polk’s Columbus (Franklin County, Ohio) City Directory 1934. R. L. Polk & Company Publishers, 1934. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/4000842

Polk’s Columbus (Franklin County, Ohio) City Directory 1938. R. L. Polk & Company Publishers, 1938. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/3791255

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

“Table of Organization and Equipment No. 6-337: Field Artillery Battery, Motorized, 155-mm Howitzer, or 4.5-inch Gun, Tractor Drawn.” War Department, September 27, 1944. Military Research Service website. http://www.militaryresearch.org/6-337%2027Sep44.pdf

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, 10/16/1940–3/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_01_00004-00413

Last updated on December 21, 2022

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.