| Residences | Occupation |

| Born in Germany, lived in Pennsylvania and Delaware | Career soldier |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 6686276 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Cannon Company, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Silver Star, Purple Heart | Operation Torch |

| Military Occupational Specialty (Presumed) | Entered the Service From |

| 651 (platoon sergeant) | Wilmington, Delaware |

Early Life & Family

There are many contradictory details about George Isadore’s early life. It appears that he was born Georg Isidorozyk in Germany on April 9, 1909—at least, that was his date of birth listed in his military records. His parents, Lawrence (also known as Lorenz, Larenz, or Laurence depending on the record) and Anna Isidorozyk, were ethnically Polish. He had at least six siblings: three older brothers, an older sister, a younger brother, and a younger sister. An S.S. Haverford passenger manifest stated that he and his family sailed from Liverpool, England, on October 19, 1910, and arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on October 31, 1910.

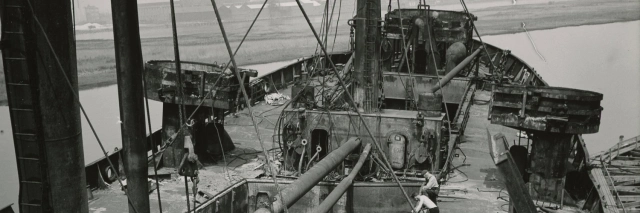

The family initially settled in Reading, Pennsylvania, and changed their name to Isadore. The family was still living there as of September 12, 1918, when Lawrence Isadore registered for the draft. Curiously, it appears that the family claimed that George Isadore was born in Reading: Journal-Every Evening reported it as his birthplace. The census recorded the Isadore family on March 10, 1920, living in the Minquadale Terrace area of New Castle, Delaware. Lawrence Isadore was working as a carpenter in a shipyard. Curiously, the census recorded the family’s arrival in 1909 rather than 1910 and stated that George Isadore had born in Pennsylvania.

Isadore’s father, who eventually ran a grocery store, ran afoul of liquor laws during Prohibition. Every Evening reported on October 10, 1923, that the Isadore home had been raided the day before for the third time by federal agents and “A small quantity of finished liquor and two barrels of mash were seized.”

Journal-Every Evening reported that Isadore “attended the Rose Hill Public School.” A medal citation stated that Isadore was living in Wilmington, Delaware, when he entered the service.

Prewar Military Career

Isadore had a varied career in the interwar U.S. Army, serving in no fewer than four different branches. The Army had few opportunities for advancement during those years. Often, transfers were not possible, meaning a soldier who wished to change units had to do so between enlistments (and start back over as a private).

Isadore joined the U.S. Army in 1927 at age 18. He joined Service Troop, 1st Cavalry at Camp Marfa, Texas, on July 7, 1927. It appears that troop was disbanded effective January 18, 1918 (or February 1, 1918, according to another roster). Private Isadore transferred to Troop “E” of the same regiment. He was promoted to private 1st class in October 1928. On October 2, 1929, his unit temporarily left Camp Marfa for Fort Bliss, Texas. They departed Fort Bliss on November 12, 1929, arriving back at Camp Marfa one week later. Effective January 1930, Camp Marfa was renamed Fort D. A. Russell. On April 18, 1930, Private 1st Class Isadore went on detached service at Fort Clark, Texas, rejoining his unit on May 21, 1930. He was honorably discharged at the end of his enlistment on August 10, 1930.

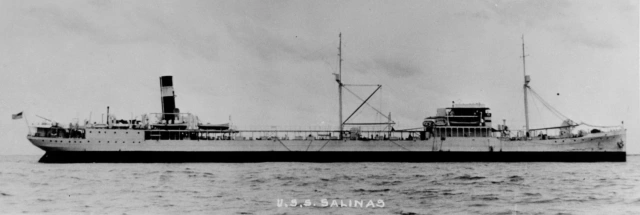

Isadore apparently reenlisted in early 1931, this time into the Corps of Engineers. He was briefly stationed at Fort Slocum, New York, before he departed for the Panama Canal Zone aboard the U.S.A.T. Chateau Thierry on March 26, 1931. On April 4, 1931, he arrived in Corozal, Canal Zone, where he joined Company “C,” 11th Engineers. He remained with that unit for the next two years. On April 11, 1933, he departed the 11th Engineers for reassignment back at the depot in Brooklyn, New York, boarding Chateau Thierry again that same day.

After returning to New York that same month, Private Isadore was originally earmarked for the 7th Coast Artillery at Fort Hancock, New Jersey. The transfer never took place and he remained assigned to Headquarters Detachment 2nd Corps Area on Governors Island, New York. He was promoted back to private 1st class in August 1933 and honorably discharged on May 25, 1934.

Isadore reenlisted again as a private in the Field Artillery that summer. He joined Battery “C,” 16th Field Artillery at Fort Myer, Virginia, on July 28, 1934. He was promoted to private 1st class on October 25, 1935, and to corporal on February 13, 1936. He was promoted to sergeant on October 1, 1936, and honorably discharged on July 24, 1937, at the end of his term of service.

A few weeks later, Isadore reenlisted in the Infantry at the U.S. Army Recruiting Station in Camden, New Jersey, on August 9, 1937. Although not restored to his previous grade, Private Isadore did receive a furlough until the following month. On September 8, 1937 (according to a roster), or September 15, 1937 (according to a morning report), he reported to Fort Jay at Governors Island, New York, where he joined Company “E,” 16th Infantry Regiment. They 16th Infantry was part of the 1st Division (known as the 1st Infantry Division after May 15, 1942). On October 16, 1937, Isadore was promoted to private 1st class. He was promoted to corporal on February 23, 1938.

Corporal Isadore remained with the unit during several moves in 1939: from Fort Jay to Fort Dix, New Jersey; back to Fort Jay; and finally, to Fort Benning, Georgia. Corporal Isadore was still with Company “E” as of December 31, 1939. After participating in the Louisiana Maneuvers in the spring of 1940, the regiment headed back to Fort Jay but moved again in February 1941 to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, where it was stationed at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

World War II

After the U.S. entry into World War II, the 16th Infantry moved several times:

- Camp Blanding, Florida (February 1942)

- Fort Benning, Georgia (May 1942)

- Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Pennsylvania (June 1942)

Sometime between April 1940 and November 10, 1942, Isadore was promoted to staff sergeant and transferred to the new regimental cannon company. Captain David C. Ballard, Jr. wrote in a history of his unit that

Cannon Company, 16th Infantry, was activated 28 June 1942, while stationed at Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Penn. Upon activation there were no quarters [or] barracks available, so the company was quartered in the Camp Recreation Hall. One platoon on the stage, the remainder of the Company of the dance floor.

In his book, US Army Infantry Divisions 1942–43, John J. Sayen, Jr. explained why the company was added to the regiment:

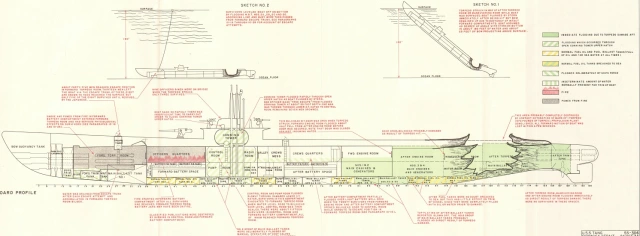

First authorized for the infantry regiment in 1942, the cannon company had been a controversial issue within the Army. The concept of a cannon company had originated during World War I. In that conflict, poor communications made it difficult or impossible for the artillery to respond to infantry calls for fire, or even to alter its scheduled fire to conform to unexpected changes in the tactical situation. […] According to its concept the cannon company should use specially designed guns that traded range and caliber for lightness, an ability to be manhandled, and a low profile. This allowed a cannon company to follow the infantry as it advanced, and deliver direct supporting fire whether communication worked or not. Cannon company personnel could see for themselves what was going on and direct their fire accordingly. The War Department saw the new 60mm and 81mm mortars as at least a partial cannon company substitute, but many officers believed that the infantry would need light cannon as well. They could not only outrange the mortars, but also use direct fire. Unfortunately, the US Army never developed any light artillery pieces suitable for a cannon company. Therefore the War Department substituted heavier weapons originally designed as division-level artillery.

It is unclear when Isadore joined Cannon Company, 16th Infantry Regiment, but it is likely that it was around the time the unit was activated in June 1942. He would have been a logical choice given his years of service in a Field Artillery unit. Journal-Every Evening reported that his last visit to his family on furlough occurred that same month.

Remarkably, Cannon Company was not issued any artillery for several months. Captain Ballard wrote that “No training devices were available other than a limited amount of Training Manuals. This training proved unsatisfactory due to changes and modifications made on the equipment.”

On August 1, 1942, the 16th Infantry sailed for the United Kingdom. After arriving in Scotland six days later, the regiment moved to Tidworth Barracks, England. Even then, Cannon Company had to rely on their manuals for artillery training. Finally, they were briefly issued eight self-propelled guns (six T30 Howitzer Motor Carriages and two 105 mm Howitzer Motor Carriage M7s, now often referred to by their British nickname, the Priest). Captain Ballard explained:

Six half-tracks with 75mm Howitzers mounted, and two 105 mm Howitzers, M-7, were issued to the Company in late August. These vehicles remained in the Company two days. During this two day period, they were cleaned and prepared for Overseas Shipment. The next time the men of Cannon Company saw the guns, they had been unloaded from a Supply Ship and were lined up on the Beach in North Africa, near Arzew, Algeria, on 8 November 1942.

Under Table of Organization No. 7-14: Infantry Cannon Company, dated April 1, 1942, the company was equipped with two 75 mm howitzer platoons, each with three H.M.C.s, as well as one 105 mm howitzer platoon equipped with two H.M.C.s. Based on the table or organization, Staff Sergeant Isadore must have been the platoon sergeant in the 105 mm howitzer platoon.

Immediately after the U.S. entry into World War II, the Americans agreed to prioritize victory in Europe over the Pacific. It soon became clear that it would be impossible to build up enough forces and amphibious capacity to launch a direct attack on Nazi-occupied Europe in 1942. Even so, there was intense pressure to get American forces into the fight and to relieve pressure against the Soviet Union by forcing the Axis to commit resources to other fronts. During the summer of 1942, Allied planners began preparing Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa.

Ironically, the first American offensive in the Mediterranean Theater would strike not the German or Italian armies, but the nominally neutral forces of America’s “oldest ally.” France’s colonies in North Africa were under the control of Vichy France, essentially an Axis-aligned rump state established after the defeat of France in 1940. Secret negotiations between the Americans and French proved fruitless prior to Torch.

During September and October 1942, Cannon Company participated in amphibious exercises in rehersal for the operation, though Captain Ballard bluntly admitted that “without the proper equipment, no interest was shown in the maneuvers.” The unit reembarked on October 19, 1942.

Simultaneous landings targeting French possessions in Morocco and Algeria began early on November 8, 1942. The 1st Infantry Division was part of Center Task Force, with orders to capture the important port city of Oran, Algeria. American troops began landing at 0100, unopposed in some areas. Two hours later, the Allies launched the ill-conceived Operation Reservist, in which two British sloops attempted to sail American troops directly into Oran’s harbor, hoping that the French would not resist. Instead, both ships were sunk and all the men aboard killed, wounded, or captured. As Brian Lane Herder explained in his book, Operation Torch 1942: The invasion of French North Africa:

Some French commanders and units chose not to fight the Allies; they welcomed the foreign army that might eventually destroy Nazi Germany. Most French units, however, resisted the Allies stubbornly. As faithful soldiers those that fought expected to defend against any invaders as long as possible. Typically these units ceased hostilities only when militarily defeated or when a clearly superior French official ordered them to lay down their arms.

The 16th Regimental Combat Team began landing to the east of Oran near Arzew at 0100 hours. The first members of Staff Sergeant Isadore’s Cannon Company, a reconnaissance party, landed at 0430, with the rest of the personnel arriving at 0930. However, it was only at 1130 that the first two 75 mm howitzers arrived, with another landing that afternoon and a fourth the following morning. Not until 1600 hours the following day did the rest of the company’s artillery arrive, including the two 105 mm M7s.

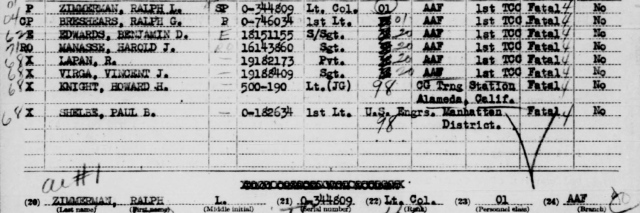

For Staff Sergeant Isadore, a military career spanning some 15 years came down to a single day of combat: November 10, 1942. Captain Ballard wrote of the day’s action:

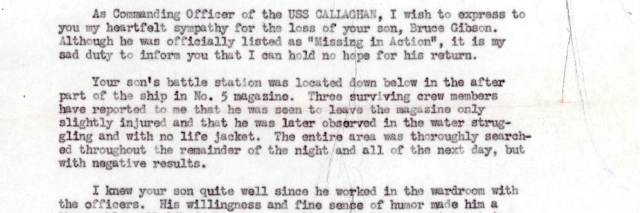

The 2nd Bn [Battalion, 16th Infantry] was held up in the vicinity of Ferme Cantne by heavy enemy fire. About 0200 hours, a coordinated attack was planned by the 2nd Bn, and Cannon Company laid down preliminary fires from 0345 to 0400. From 0400 to 1130 Cannon Company continued to support the 2nd Bn, knocking out enemy strong points in the vicinity of Ferme St. Jean Baptiste. At 1130 the Company took direct firing positions on high ground overlooking Oran, continuing to support the advance of the 2nd Bn. The capture of Oran terminated the action against the enemy. Casualties for this day; One (1) S/Sgt killed – One (1) Sgt and One (1) Pvt wounded.

Staff Sergeant Isadore was that fatality, the first suffered by Cannon Company, 16th Infantry. A hospital admission card with his service number stated that he was killed by a gunshot wound. French forces in and around Oran capitulated that same afternoon, with the rest of the Vichy forces in Morocco and Algeria following suit soon after. The fighting had been costly. Herder wrote:

Torch’s November 8–10 combat is too often dismissed as a historical footnote. Yet in three days defending North Africa against the Anglo-Americans, the French had suffered 3,343 casualties, including 1,346 killed. When including French- and Axis-inflicted naval losses, total Allied combat casualties climb to 2,661, including 1,331 killed or missing – fully 30 percent that suffered by the lionized June 6, 1944 Normandy landings.

Operation Torch’s aftermath was bittersweet. Many of the captured Vichy French soldiers now joined the Allies. The Germans quickly occupied the Vichy-controlled areas of mainland France. Neither side claimed the bulk of the French fleet at Toulon, its ships scuttled by their crews before the Germans could seize them. German reinforcements flowed into Tunisia, ensuring that combat would continue in North Africa for another seven months, though the subsequent Tunisia campaign ended with a resounding Allied victory.

On December 7, 1942, Staff Sergeant Isadore was posthumously awarded the Silver Star per General Orders No. 33, Headquarters 1st Infantry Division. The citation stated in part:

For gallantry in action in the vicinity of Ferme Cantne, Algeria, November 10, 1942. During the Oran offensive, Sergeant Isadore directed the fire of his self-propelled 105 mm howitzer against an enemy strongpoint. The fire of his weapon contributed greatly to the eventual reduction of the strongpoint, allowing the rifle elements of the Second Battalion to advance. While directing this fire, Sergeant Isadore was mortally wounded.

At a ceremony on the parade ground at Fort DuPont, Delaware, on March 26, 1943, Colonel George Ruhlen presented Staff Sergeant Isadore’s sister, Anna Hilton, with the Silver Star and the Purple Heart that he had earned. Journal-Every Evening reported that “Nearly 1,000 soldiers, veterans and state officials attended” the ceremony, including a total of four of Staff Sergeant Isadore’s siblings and Delaware Governor Walter W. Bacon.

After the war, Staff Sergeant Isadore’s body was repatriated to the United States and buried at Baltimore National Cemetery in Maryland on June 9, 1948.

Notes

Father & Last Name

Lawrence Isadore was from the Province of Posen. It’s unclear if the rest of the Isadore family was born there. After Lawrence Isadore died in 1934, it appears that his wife and some of his children changed their last name to Hilton. As a result, some newspaper articles erroneously refer to him as George Isadore Hilton.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Military Research Service for providing Table of Organization No. 7-14.

Bibliography

“4 Delaware Soldiers Killed in Africa Raid.” Journal-Every Evening, January 2, 1943. Pg. 1 and 10. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/106019164/isadore-kia-1/, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/106019284/isadore-kia-2/

Ballard, David C., Jr. “The History of Cannon Company 16th Infantry Regiment First Infantry Division.” 1945.

Clay, Steven E. U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919–1941, Volume 1. The Arms: Major Commands and Infantry Organizations, 1919–41. Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16040coll3/id/198/rec/3

“CT-16 Report Torch Operation.” Headquarters CT 16, November 21, 1942. https://firstdivisionmuseum.nmtvault.com/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=5d51b39f-52d3-4177-b65e-30b812011812%2Fiwfd0000%2F20141124%2F00000363

“General Orders Number 33, Headquarters 1st Infantry Division.” December 7, 1942. First Division Museum, Cantigny Park, Illinois. https://firstdivisionmuseum.nmtvault.com/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=5d51b39f-52d3-4177-b65e-30b812011812%2Fiwfd0000%2F20151021%2F00000027

Herder, Brian Lane. Operation Torch 1942: The invasion of French North Africa. Osprey Publishing, 2017.

Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_2421406274_0449-04570

“Isadore Arrested After Third Raid.” Every Evening, October 10, 1923. Pg. 4. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/101268103/isadore-prohibition/

Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917–1938. Record Group, 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61174/images/44508_3421606189_0066-00166

Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917–1938. Record Group, 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61174/images/44509_3421606198_0019-00695

“Minquadale Man Dies Battling Axis In Western Europe.” Wilmington Morning News, December 4, 1942. Pg. 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/106019733/isadore-death/

Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Record Group 85, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8769/images/PAT840_85-0181

Sayen, John J., Jr. US Army Infantry Divisions 1942–43. Osprey Publishing, 2006.

“Sister Is Presented With Posthumous Awards At Ft. DuPont on Behalf of Sergeant Isadore.” Journal-Every Evening, March 27, 1943. Pg. 3. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/101270262/george-isadore-medals/

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

“Table of Organization No. 7-14: Infantry Cannon Company.” War Department, April 1, 1942. Courtesy of Military Research Service. http://www.militaryresearch.org/

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4295772-00157

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531891_00410

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02627-00072

U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/701461288/blank-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

U.S. Army Enlisted and Officer Rosters, July 1, 1918–December 31, 1939. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-D3CH-H9PB-2 (July 1927), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-D3CH-H9NZ-K and https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CH-H9NL-X (January 1928), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CH-H96X-H (February 1928), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-D3CH-H9K1-5 (October 1928), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CH-H9J8-X (October 1929), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CH-H9NJ-2 (November 1929), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CH-H9VT-Z (January 1930), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CH-H962-7 (April 1930), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CH-H9KB-Q (May 1930), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-D3CH-H9P6-M (August 1930), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-LQLV (April 1931), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-29ZN-B (April 1933), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-X3C6-5GXY (August 1933), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3C6-52QD (May 1934), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-X3CV-99D3-P (July 1934), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CV-SWSR (October 1935), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-X3CV-SQBL (February 1936), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-X3CV-S79X (July 1937), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-J367-4CPG (August 1937), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-J367-4X26 (September 1937), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-T5RD (December 1939)

World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005266926_03823

Last updated on May 6, 2023

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.