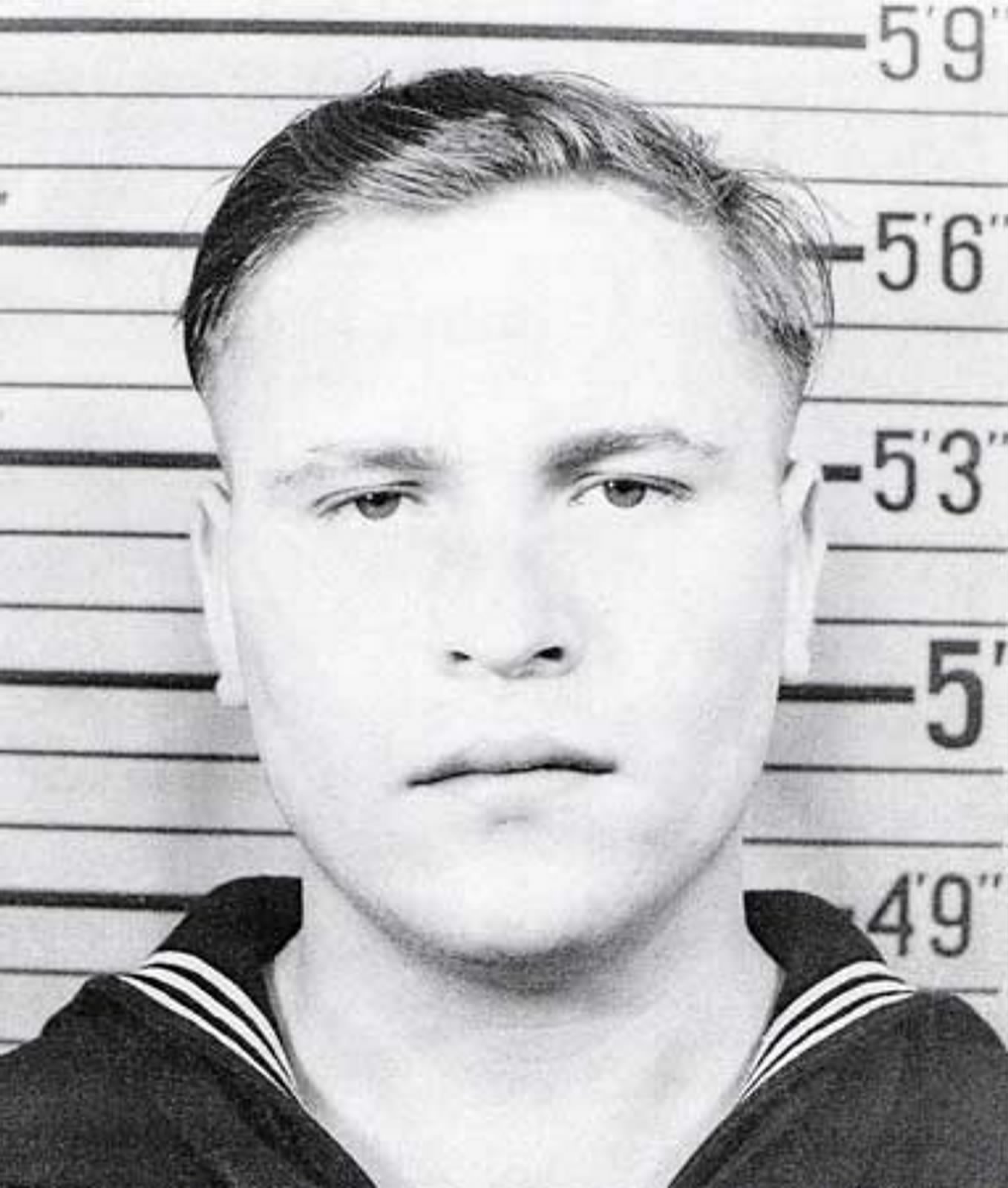

| Hometown | Occupation |

| Irwin, Iowa | Career sailor |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Navy | 3213006 |

| Theater | Vessel |

| Pacific | U.S.S. Tang (SS-306) |

Author’s note: Delaware’s World War II Fallen occasionally highlights men and women without any known connection to the First State. This article was inspired by previous history reading about the dramatic fight for survival by the crew of the U.S.S. Tang (SS-306).

Early Life & Family

Paul Lewis Larson was born in Irwin, Iowa, on December 26, 1919. It appears that he was the eldest child of Roy L. Larson (1893–1964) and Anna W. Larson (née Paulsen, 1892–1989). His father, a World War I veteran, was a farmer at the time but later worked in trucking, operated a service station, and had an insurance business. Larson had three brothers (one of whom died as an infant) and two sisters.

Larson was recorded on the census in January 1920 living with his parents and paternal grandmother on a farm in Jefferson Township, Shelby County, Iowa. By the time of the next census, recorded on April 8, 1930, Larson was living on Bella Street in Irwin with his parents, grandmother, and three younger siblings. Larson graduated from Irwin High School in 1937.

Navy Career & Marriage

Larson volunteered for the U.S. Navy in Des Moines or Carroll, Iowa—there are different entries in various U.S. Navy muster rolls—enlisting on February 21, 1939. Both of his surviving brothers followed him into the Navy and served in the Pacific during World War II. Robert Wayne Larson (1921–1988) enlisted on October 18, 1939, and Richard LeRoy Larson (1924–1986) joined on January 24, 1944.

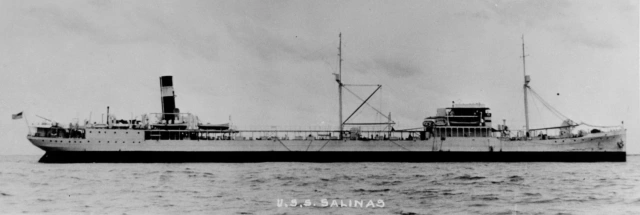

By May 1939, Larson was assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. On April 9, 1940, he was recorded on the census as a hospital apprentice at the Naval Training Station in San Diego, California. Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Larson was transferred from the Naval Training Station to the Naval Receiving Station, San Diego, on May 10, 1941. Larson joined the crew of the destroyer U.S.S. Dale (DD-353) on June 20, 1941.

Dale was present at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked on December 7, 1941. Although attacked by aircraft after it got underway, the ship wasn’t hit. Four days later, he mailed a letter to his parents that he was safe. During 1942, Dale performed escort duties for American aircraft carriers and troop convoys.

Larson was promoted to pharmacist’s mate 2nd class on May 1, 1942. On October 18, 1942, he transferred from the Dale to the destroyer tender U.S.S. Dixie (AD-14) for reassignment. On December 20, 1942, he sailed aboard the transport U.S.S. Henderson (AP-1) as a passenger bound for California after being transferred from Pearl Harbor.

Larson married Margaret Caryl Ruhs (who went by her middle name, 1921–2015?) in Omaha, Nebraska, on January 7, 1943. His bride had also graduated from Irwin High School in 1939, two years after Larson, and was a manager at a beauty salon. Three days after the wedding, he started back to Hawaii for a new assignment. On February 4, 1943, he arrived back in Hawaii and transferred to the Naval Hospital at Pearl Harbor. He was promoted to pharmacist’s mate 1st class by the end of 1943.

A January 2, 1944, article in the Council Bluffs Nonpareil stated that Larson and his brother Bobby had been back in Iowa “enjoying a 30-day furlough.” Paul left home for the final time on December 27, 1943, to return to Pearl Harbor. On January 1, 1944, Larson sailed from Bremerton, Washington, as a passenger aboard U.S.S. Litchfield (DD-336), arriving at Pearl Harbor on January 6 and reporting to Submarine Base 128. On February 17, 1944, he was transferred from Submarine Base 128 to Submarine Division 42 as part of a relief crew. Relief crews, typically rookie submariners, were responsible for maintenance and repairs on submarines returning from war patrols.

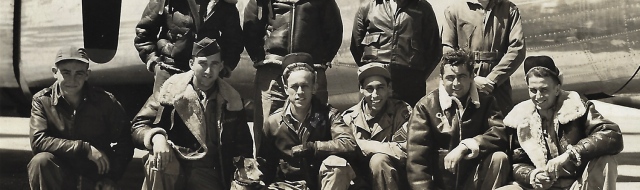

On June 3, 1944, Larson joined the crew of one of most successful American submarines, U.S.S. Tang (SS-306), commanded by Richard H. O’Kane (1911–1994). Submarine crews were too small to have a doctor on board. Pharmacist’s mates, typically referred to as “doc” by their shipmates, provided medical care during war patrols. Larson served aboard Tang during its third, fourth, and fifth war patrols. In his book Escape from the Deep, Alex Kershaw described Larson as a “soft-spoken Iowan, a favorite with all the men aboard[.]” Larson had been promoted to chief pharmacist’s mate by the fifth patrol.

Trapped Aboard a Sunken Submarine

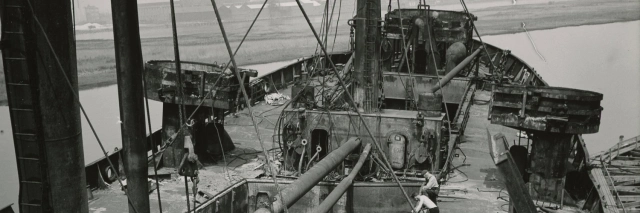

By a quirk of fate, during preparations at Pearl Harbor before Tang’s fifth patrol, the boat received a load of Mark 18 Mod 1 torpedoes that had been earmarked for another submarine, U.S.S. Tambor (SS-198), which was still being refitted. On September 24, 1944, Tang set sail for the Formosa (Taiwan) Strait, a choke point in the sea lines of communication between Japan and its empire. During the patrol, Tang sank multiple Japanese ships in a series of attacks during October 11–25, 1944. The final attack, which began off Turnabout (Niushan) Island on the evening of October 24, 1944, was among Commander O’Kane’s most daring. Tang made a night surface attack on a convoy consisting of an estimated 14 ships and 13 escorts. O’Kane claimed three transports, two tankers, and a destroyer sunk.

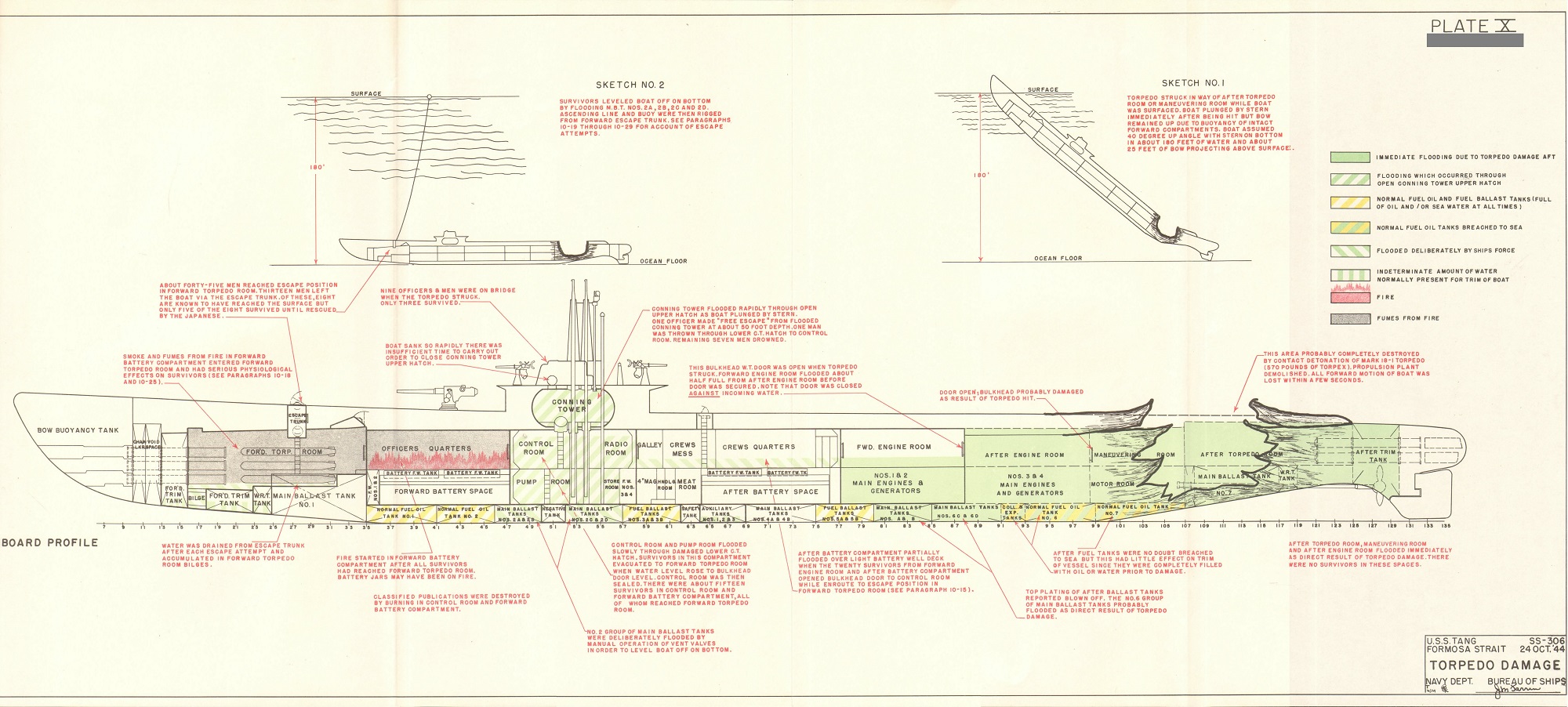

Early on the morning of October 25, 1944, O’Kane fired the boat’s last two torpedoes to finish off one of the damaged transports. One sank the target, but the final torpedo went into circular run. Commander O’Kane noted in his book, Clear the Bridge!, that unlike the torpedoes used by surface ships, American “submarine torpedoes were not fitted with anti-circular run devices, a relatively simple addition to send them into a dive should they turn beyond a specific limit.”

Despite desperate evasive maneuvers, the torpedo struck Tang’s stern. The submarine sank quickly. All men in aft engine room, maneuvering room, and aft torpedo room were killed by the explosion or drowned, as did all but two men in the conning tower. The nine men topside went into the water and one escaped from the conning tower as the boat sank. Of those ten men, four of them, including Commander O’Kane, managed to stay afloat until rescued.

The remaining crew, including Doc Larson, were trapped in the sunken submarine. Tang’s stern hit the seafloor, leaving the submarine suspended in the water at a 40-degree angle. The submarine’s watertight doors and the relatively shallow water saved them for the moment, but many had been severely injured. Their ordeal was only just beginning.

Based on survivors’ accounts, O’Kane later wrote in his report that the crew “leveled the boat off[…] and proceeded to the forward torpedo room carrying the injured in blankets.” Depending on the account, between 30 and 45 men made it to the forward torpedo room, where an escape trunk was located. Leveling off the submarine on the bottom of the Formosa Strait made it possible for most of the survivors to evacuate to the forward torpedo room. Unfortunately, it drastically increased the depth of the water that the survivors would have to escape through.

At sub school, crewmembers had trained with an escape device, a rebreather known as a Momsen lung. The submariners would have to wait in the escape trunk while the pressure equalized, then use their Momsen lungs to breathe as they followed an ascending line secured to a buoy. Training escapes at sub school were made from a depth of 50 feet (with a 100-foot-deep escape optional), but those escaping Tang would have to do so from a depth of about 180 feet. Furthermore, there evidently had not been adequate refresher training on escape procedures since sub school. One Tang survivor quoted in a U.S. Navy report about the loss reported:

Difference of opinion among the first men attempting escapes wasted valuable minutes. The men weren’t sure of escape procedure and were afraid they would make a mistake that would be fatal to the men below. Escape procedure is very simple on paper but somewhat different where everyone’s life depends on it.

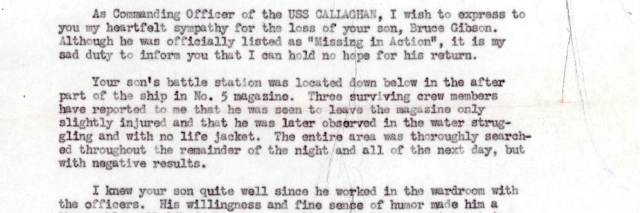

Depth charge attacks by the convoy’s escorts delayed the crew from escaping for a few hours and started a fire in the adjoining battery compartment. The resulting heat, smoke, and buildup of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide apparently rendered some of the men unconscious and sapped the will of others to attempt escape. An estimated 13 men escaped from the submarine in five parties, but five of those were never seen again. Five men survived the ascent in good shape. Perhaps unwilling to abandon the wounded until the very end, Doc Larson stayed in the submarine until the last known escape party.

In his book, Escape from the Deep, Alex Kershaw wrote that when Larson surfaced, “Blood was running out of his ears, his nose, and his mouth.” Similarly, in The Bravest Man, William Tuohy wrote that “Larson was only semi-conscious, probably dying. He had difficulty keeping his head above water.”

Whether due to equipment failure or because, in his hypoxic state, he had failed to exhale during his ascent, it appears that Larson was mortally injured by pulmonary barotrauma. Somehow, his shipmates kept his head above water in the hours that followed until the survivors were picked up by a Japanese patrol boat. It is unclear if Larson was still alive at that point. He failed to respond when the Japanese crew slapped him and they threw him overboard.

Only nine members of Tang’s crew of 87 men survived. Despite enduring months of brutality at the hands of the Japanese, all nine survived the war. The crew was initially declared missing in action. On January 7, 1946, the Navy changed the status of Larson—and the other members of the crew not freed from Japanese prisons after the war—to presumed dead. Chief Pharmacist’s Mate Larson was posthumously awarded the Silver Star Medal.

Larson’s widow remarried on March 29, 1946, to another sailor, Byron F. Clark (1919–2004). The couple had three children.

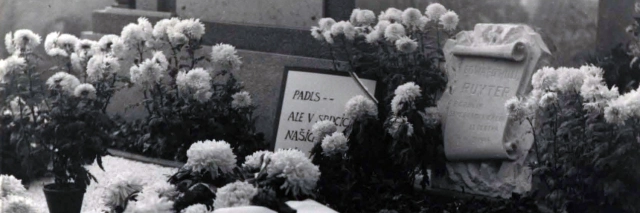

Chief Pharmacist’s Mate Larson’s name is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines, and on a cenotaph at Oak Hill Cemetery in Irwin, where his parents and his brother, Richard, were buried after their deaths.

Notes

Date of Birth

It is surprisingly common for there to be discrepancies in the date of birth in various records for World War II fallen. In many cases the day is consistent but not the year. It appears that no contemporary birth certificate was issued for Larson. The Iowa State Department of Heath Division of Vital Statistics issued a delayed birth certificate in 1946 that listed his date of birth as December 26, 1920, with supporting evidence listed as a 1931 insurance policy and a 1933 school record. When his mother submitted an application for World War II service compensation to the state of Iowa, she also listed his date of birth as December 26, 1920, and the date appears on his cenotaph at Oak Hill Cemetery.

However, a Lutheran church record recorded Larson’s date of birth as December 26, 1919, and his baptism as October 10, 1920. There is also an affidavit of birth issued in 1938 that initially listed his date of birth as December 26, 1920, but a handwritten annotation made on an unknown date corrected that to 1919. Perhaps the most conclusive evidence that Larson was born in 1919 is the fact that he was recorded on the 1920 census, which listed him as one month old as of January 1920. Had he been born in December 1920, he would not have been recorded on the 1920 census at all.

Mother’s Middle Name

Various records spelled Anna Larson’s middle name as Wilhelmine or Wilhelmina, though most including her signature and headstone simply list her middle initial of W.

Widow’s Year of Death

I have been unable to confirm Caryl Clark’s date of death beyond the fact that 2015 is listed in some family trees on Ancestry.com.

Why Did Tang’s Crew Level Off After the Submarine Sank?

Had they not leveled off the submarine, it is possible that there would have been more survivors among the men already in the forward torpedo room. After all, they would have been able to escape from shallow water. However, the men in other compartments would have been doomed. In addition, with the bow sticking out of the water, it is possible that the escorts would have located and finished off Tang before very many men escaped. It may have even enabled the Japanese to achieve the major intelligence and propaganda coup of salvaging the submarine.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Shelby County Historical Museum and On Eternal Patrol for the use of their photos.

Bibliography

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4584438_00612

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4300830_00752

Hargis, Robert. US Submarine Crewman 1941–45. Osprey Publishing, 2003.

“Irwin Sailor Home on Furlough From Pearl Harbor.” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, January 5, 1943.

Kershaw, Alex. Escape from the Deep: The Epic Story of a Legendary Submarine and Her Courageous Crew. Da Capo Press, 2008.

Margaret Caryl Ruhs birth certificate. Iowa Delayed Birth Records, 1856–1940. State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61441/images/101767312_01181,

Muster Rolls of U.S. Navy Ships, Stations, and Other Naval Activities, 1/1/1939–1/1/1949. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32662_240991-00014 (September 1941), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32662_240991-00095 (May 1942), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32662_240991-00163 (October 1942), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32859_243023-01133 (December 1942), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32859_243023-01215 (January 1943), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32859_243023-01336 (February 1943), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32861_248784-00214 (January 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32862_253858-00472 (February 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32862_253003-00044 (June 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32862_253003-00067 (October 1944)

O’Kane, Richard H. Clear the Bridge!: The War Patrols of the U.S.S. Tang. Rand McNally & Company, 1977.

O’Kane, Richard H. “U.S.S. TANG (SS306) – Report of War Patrol Number Five.” September 10, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/300337447

“Open 1942 Sessions of Board Huddled Around a Fireplace.” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, January 5, 1942.

“Paul Lewis Larson.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/30885588/paul-lewis-larson

Paul Lewis Larson affidavit of birth. Iowa Delayed Birth Records, 1856–1940. State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61441/images/101767310_02726

Paul Lewis Larson delayed certificate of birth. Iowa Delayed Birth Records, 1856–1940. State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61441/images/101713791_02836

“Seen and Heard.” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, January 10, 1943.

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00447-00578

“Southwest Iowa Marriages.” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, January 14, 1944.

“Southwest Iowa Society News.” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, December 26, 1944.

“Southwest Iowa Society News.” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, January 2, 1944.

“Submarine Report Depth Charge, Bomb, Mine, Torpedo and Gunfire Damage Including Losses in Action 7 December, 1941 to 15 August, 1945 Volume 1.” Preliminary Design Branch, Bureau of Ships, Navy Department, January 1, 1949. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/w/war-damage-reports/submarine-report-vol1-war-damage-report-no58.html

Tuohy, William. The Bravest Man: Richard O’Kane and the Amazing Submarine Adventures of the USS Tang. Presidio Press, 2006.

WWII Bonus Case Files. State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61186/images/45280_1020705384_1018-00239

“Your Neighbors’ Doings.” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, May 29, 1939.

Last updated on July 17, 2022

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.