| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| New Jersey, Pennslyvania | Worker for the De Laval Steam Turbine Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | O-338819 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 1222 (tank destroyer unit commander) | Tunisia, Naples-Foggia, Anzio, and Rome-Arno campaigns |

Author’s note: Today is the 80th anniversary of the fourth assault on Villa Crocetta, Italy, which occurred on May 29, 1944. This is fourth in a series of profiles of men killed during that assault.

Delaware’s World War II Fallen occasionally highlights men and women without any direct connection to the First State. This article incorporates some text from my previous articles “1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie: Jack in the Alice Griffin Letters” (published at the 32nd Station Hospital website), “Captain William W. Galt: ‘Always Out In Front’” (published on the Congressional Medal of Honor Society website), and this site’s “Sergeant Robert D. Lightsey (1911–1944).” Coincidentally, Lieutenant Jarvie’s name is honored in Delaware due to a shared Delaware-New Jersey memorial.

Early Life & Family

John Scott Jarvie was born on November 16, 1914, in Trenton Junction (now West Trenton), New Jersey. He was the sixth child of Albert Louis Jarvie (1882–1938) and Daisy Olive Jarvie (1886–1956). Jarvie’s father worked in a variety of jobs over the years: pressman, laborer, and poultry farmer. His mother had immigrated from Sweden as a child. At least one of Jarvie’s older siblings died before he was born. It appears that he had three older brothers, two older sisters, and four younger brothers.

The Jarvie family apparently moved several times across the Delaware River, or they split their time between the Trenton area of New Jersey and nearby Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Jarvie’s parents were described as living in Yardley, Pennsylvania, at the time his father registered for the draft on September 12, 1918. The family was recorded living on Longshore Avenue in Yardley on the census taken in January 1920. Jarvie’s younger brother, Philip Henry Jarvie (1921–1997), was born in West Trenton on July 28, 1921, suggesting the family had returned to New Jersey.

By the time of the next census in April 1930, Jarvie’s parents may have been separated or divorced. Jarvie was listed as living at 115 Olive Avenue in Trenton with his mother (inaccurately described as widowed in the record), five siblings, his brother-in-law, and two nieces.

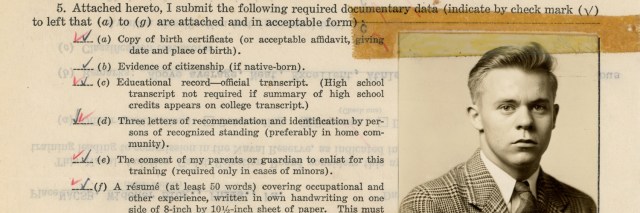

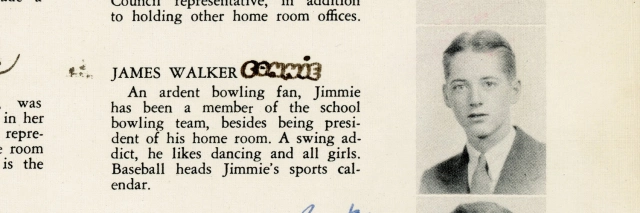

Jarvie graduated from high school at the Bordentown Military Institute in 1936. He was described as standing five feet, 8¾ inches tall and weighing 145 lbs. by the time of his military service. He was Episcopalian.

Jarvie was working as a laborer when he married Bertha May Koller (1919–2003) in the chapel of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in Trenton on May 29, 1937. The couple made their home with her parents at 351 Centre Street in Trenton.

The next few years appear to have been a difficult period in Jarvie’s life. Amidst the Great Depression, he struggled to find work. His father died suddenly of appendicitis on March 16, 1938. On August 11, 1938, the Trenton Evening Times announced that Jarvie was one of several men who “qualified for appointment as ambulance driver in the city employ” but he apparently wasn’t hired. The same paper announced on March 28, 1940, that Jarvie was one of 87 men who had passed an exam qualifying them to be hired by the Trenton Police Department, but the article also noted: “There are no vacancies at this time.”

According to the census taken in April 1940, Jarvie had been unemployed for three years, though it also described him as a college graduate. If correct, that indicates Jarvie pursued higher education after graduating from Bordentown. He was living at a home on Princeton Turnpike in Lawrence Township, New Jersey, with his brother, Walter G. Jarvie (1908–1971), and his brother’s family. At the same time, his wife was living with her family in Trenton and employed doing clothing alterations. That suggests he was estranged from his wife, although the couple remained married until his death.

By 1942, Jarvie was working for the De Laval Steam Turbine Company in Trenton.

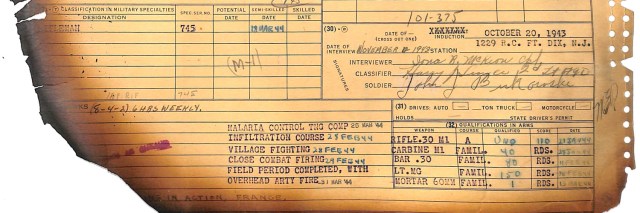

Service Stateside, England, & North Africa

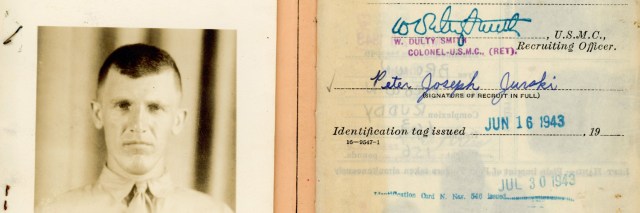

The loss of Jarvie’s personnel file in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire makes it difficult to determine very many details of his military career prior to April 1942. An officer pay card from 1944 indicates that he had seven years of service, suggesting he had served in the U.S. Army as an enlisted man since around the time he graduated from the Bordentown Military Institute. Similarly, the absence of a draft card for him from registration day, October 16, 1940, suggests that he was already in the military. Details of his employment history in the 1930s indicates that he served only briefly on active duty, or not at all. It is also unclear if he was a member of the Enlisted Reserve Corps—an extremely small organization at the time—or the National Guard.

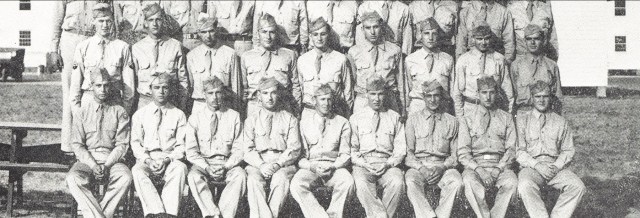

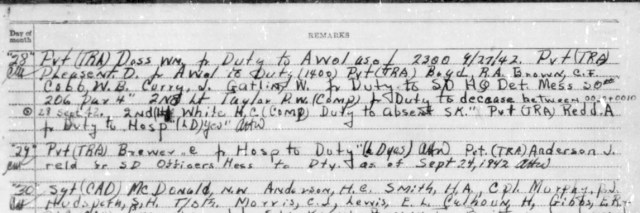

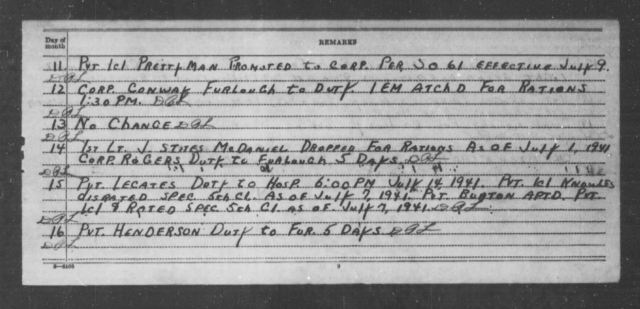

Jarvie was commissioned as an Infantry 2nd lieutenant on April 3, 1942. The following day, 2nd Lieutenant Jarvie was attached for rations for one meal to Headquarters Company, 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. During April 6–26, 1942, he was attached for rations to the battalion’s Company “A.” After attending Baker & Cooks School at Fort Benning, Georgia, beginning April 26, 1942, he officially joined Company “A” on May 11, 1942. He was appointed mess officer effective May 15. Lieutenant Jarvie briefly commanded Company “A” beginning on June 30, 1942, while the regular C.O. was on detached service.

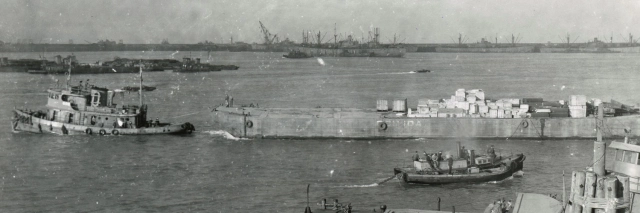

On August 1, 1942, the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion began their move to Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, arriving early the following morning. On August 5, they moved to the New York Port of Embarkation. The following day, the unit shipped out from the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the British transport Andes, arriving in Liverpool, England, on August 17, 1942. On September 9, 1942, Lieutenant Jarvie was transferred to Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

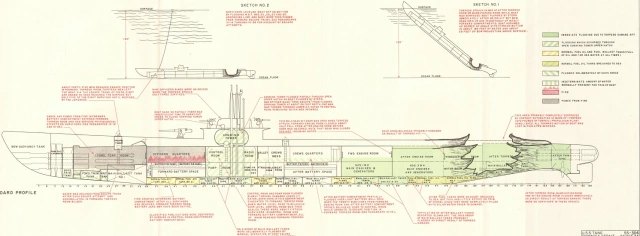

Tank destroyers were essentially defensive weapons intended to neutralize armored breakthroughs like those that occurred during the collapse of France in 1940. Since a purpose-built tank destroyer was not yet available, the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion was initially equipped with a stopgap vehicle, the M3 Gun Motor Carriage: a halftrack armed with a 75 mm gun.

Although the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion’s move to the United Kingdom was part of the buildup of American forces in Europe, it became clear that landing in France would not be practical anytime soon. The Allies agreed to strike North Africa instead in November 1942, invading Morocco and Algeria, which were under the control of the Axis-aligned Vichy France regime. In response, Axis forces surged into neighboring Tunisia.

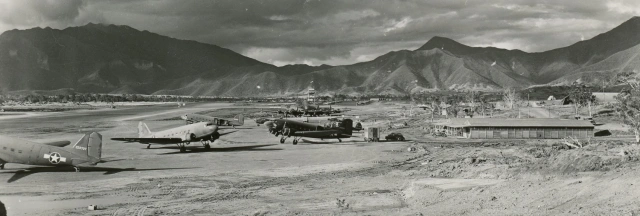

On the night of January 5, 1943, Company “C” boarded a train at Chiseldon Camp, arriving at Liverpool at 1115 hours the following day. The 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion sailed for North Africa on January 8, 1943. The battalion arrived in Algeria on January 17, 1943, and soon began traveling east to join the Tunisian campaign. Jarvie was promoted to 1st lieutenant with a date of rank of January 14, 1943, although word didn’t catch up to his unit until March 23, 1943.

The 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion first entered combat on February 20, 1943, during the American defeat at the Battle of Kasserine Pass. In a letter to his family, 1st Lieutenant (later Major) Baker D. Newton (1918–1961), then the Company “C” executive officer, recalled the unit’s baptism by fire. A few miles from the front, Company “C” was leading the battalion when they began encountering demoralized American infantry heading the other way. Soon after, three enemy armored cars approached.

Then all hell broke loose from our guns – – all firing too hastily. We hit one of them, the others escaped back into the pass. By this time we were taking somewhat of a shellacking from artillery and machine guns which had moved along the sides of the valley on our flank.

Though Kasserine Pass was a major setback, about a month later, the 894th Tank Destroyer participated in a victory, the Battle of El Guettar. The 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion led Allied forces into Bizerte, Tunisia, on May 7, 1943. This, together with the capture of Tunis the same day, effectively ended the Tunisian campaign. With those major ports in Allied hands, all Axis forces remaining in North Africa were forced to surrender within days.

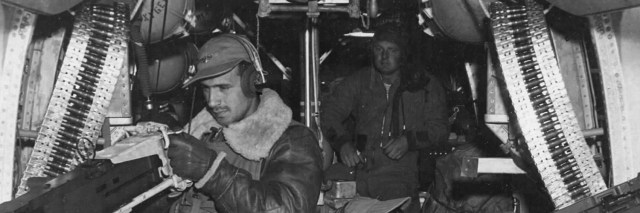

At the end of May 1943, the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion arrived at the Fifth Army Tank Destroyer Training Center near Sebdou, Algeria. There, the unit began converting to the 3-inch Gun Motor Carriage M10. The M10’s M7 3-inch gun was capable of dispatching most contemporary German armored vehicles, although the newer Panther and Tiger tanks were a greater challenge (especially at longer ranges and in instances the enemy could only be attacked from the front, which was protected by heavier armor).

The M10 was best when used in ambushes since its armor was too weak to survive a hit from all but the weakest enemy tanks. When Allied tanks were not available, tank destroyers were sometimes pressed into an offensive role for infantry support. Whereas the M4 medium tank had a fully enclosed turret and three machine guns, the M10 had an open-topped turret and a single .50 machine gun. The fact that the gun was typically mounted on the back of the turret meant the soldier using it was badly exposed to return fire. In a letter home on May 17, 1943, Captain Newton—now Lieutenant Jarvie’s company commander—grumbled: “I’d like to be back at [Camp] Hood, so I could tell the brass hats what we need. They’re preparing us to fight one way. We are used by higher authorities in every other way.”

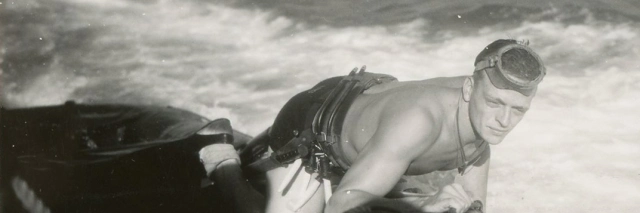

While stationed at Sebdou, Lieutenant Jarvie often visited the 32nd Station Hospital in nearby Tlemcen, Algeria. He was popular with the hospital’s nurses, earning a reputation for his thoughtfulness. He was particularly close to 2nd Lieutenant Alice Eileen Griffin (later Feeney, 1914–1963). When off duty, he regularly stopped by the hospital with a jeep, often giving Griffin and her friends a ride to nearby towns or the Mediterranean Sea. Once, he even brought back some gazelle meat after going hunting. As a result, when his unit held a party at a villa in Tlemcen on September 30, 1943, Jarvie was asked to obtain dates for 35 men, and did so successfully!

Combat in Italy

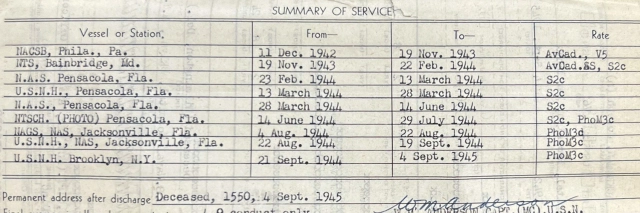

1st Lieutenant Jarvie transferred out of Company “C” on September 13, 1943, and served a stint with the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion’s Headquarters Company. He shipped out for Italy on or around October 14, 1943. After performing military police duty in Naples, the 894th returned to combat near Mignano in late December 1943. During this period, they were effectively acting as self-propelled artillery rather than in an antitank role.

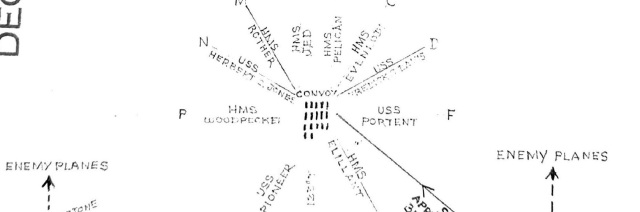

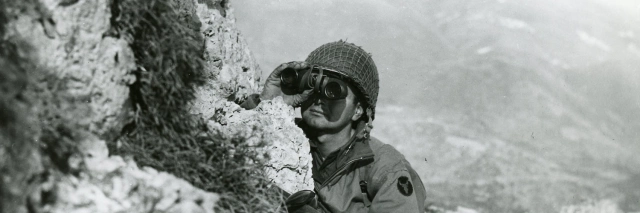

In late January 1944, Lieutenant Jarvie and his battalion arrived at the Anzio beachhead. This Allied amphibious operation threatened to cut off German forces south of Rome, and the enemy responded fiercely.

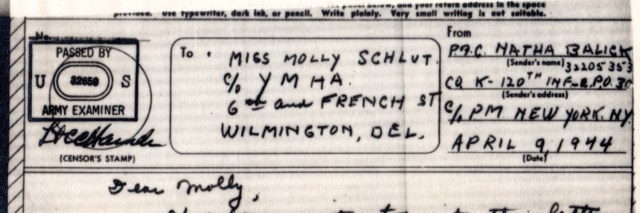

On February 3, 1944, Lieutenant Jarvie rejoined Company “C” as a platoon leader, exchanging places with 2nd Lieutenant Wesley J. Schmidt (1918–1986), who had been wounded in the foot by shrapnel four days earlier. That night, German forces launched an attack intended to crush the Campoleone salient, where Company “C” was supporting the British 1st Infantry Division. Jarvie was caught behind enemy lines.

Contemporary news accounts by a pair of Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondents differ slightly in the details. An article by Daniel De Luce (1911–2002) of the Associated Press mentioned that “Three tank destroyers […] were temporarily surrounded […] but two fought their way out under command of Lieutenants Herbert M. Siercks, Fremont, Neb., and John S. Jarvie, Trenton, N. J.”

The other article, by Homer Bigart (1907–1991) of the New York Herald Tribune, stated that Jarvie was trapped with Sergeant Leo E. Dobson (1914–1992):

Caught three miles inside the enemy lines soon after the enemy’s counter-attack began they parked in the middle of a field and kept its approaches sprayed with machine-gun fire.

From midnight to dawn the 50-calibre machine-gun mounted above the open hatch was busy. Lt. John S. Warvie, [sic] Trenton, N. J., an anti-tank officer, [relieved] Dobson occasionally while other crew members slept. T-D people are impervious to noise and although the din was like that of a boiler factory with a war contract, the crewmen dozed during the dull periods.

Some times the Germans tried to come close enough to chuck grenades into the open hatch and tried small arms fire. Dobson got one at 10 yards.

After setting up new positions, Companies “B” and “C” were instrumental in defeating German forces near Aprilia (nicknamed “The Factory”). According to the S-3 periodic report written by Captain Paul A. Baldy (1918–2008) covering the afternoon of February 3, 1944, through the afternoon of February 4, 1944:

The enemy counterattacked very strongly during the period. “B” & “C” Companies participated very actively in repulsing the attack. “C” Company destroyed four (4) Mark VI [Tiger] tanks. These have been confirmed by the British. One towed AT [antitank] gun was destroyed while its crew was attempting to get it into firing position. Two destroyers held off the German infantry with their 50 cal. for two hours. Many casualties were inflicted. We lost two M 10’s– destroyed and one captured in this action. Two enemy occupied houses were also fired into by “C” Company.

An Associated Press article dated February 5, 1944, suggests that Jarvie was one of the men involved in holding off the German infantry:

Lieutenant John S. Jarvie, 351 Centre Street, Trenton, N. J., distinguished himself during the two-day [battle] which ended today in the North Carroceto sector.

Liaison officer between American tank destroyers and British infantry, Jarvie, at one critical moment when the tank destroyers were helping the British in the line, manned a .50-calibre anti-aircraft gun on a tank destroyer […] and fired at the advancing rows of Germans. In order to get the proper angle he had to expose his body from the waist up so that he was vulnerable throughout the nearly half-hour of this kind of fighting, yet he was not even scratched.

After the failure of the German counterattacks, months of static warfare followed. The Anzio beachhead was as miserable as it was dangerous. Even when the front lines were quiet, the Germans constantly bombarded the Allied positions, often employing powerful railway guns, as well as aircraft armed with deadly antipersonnel bombs. Mobile warfare would not resume on the Anzio front until May 23, 1944.

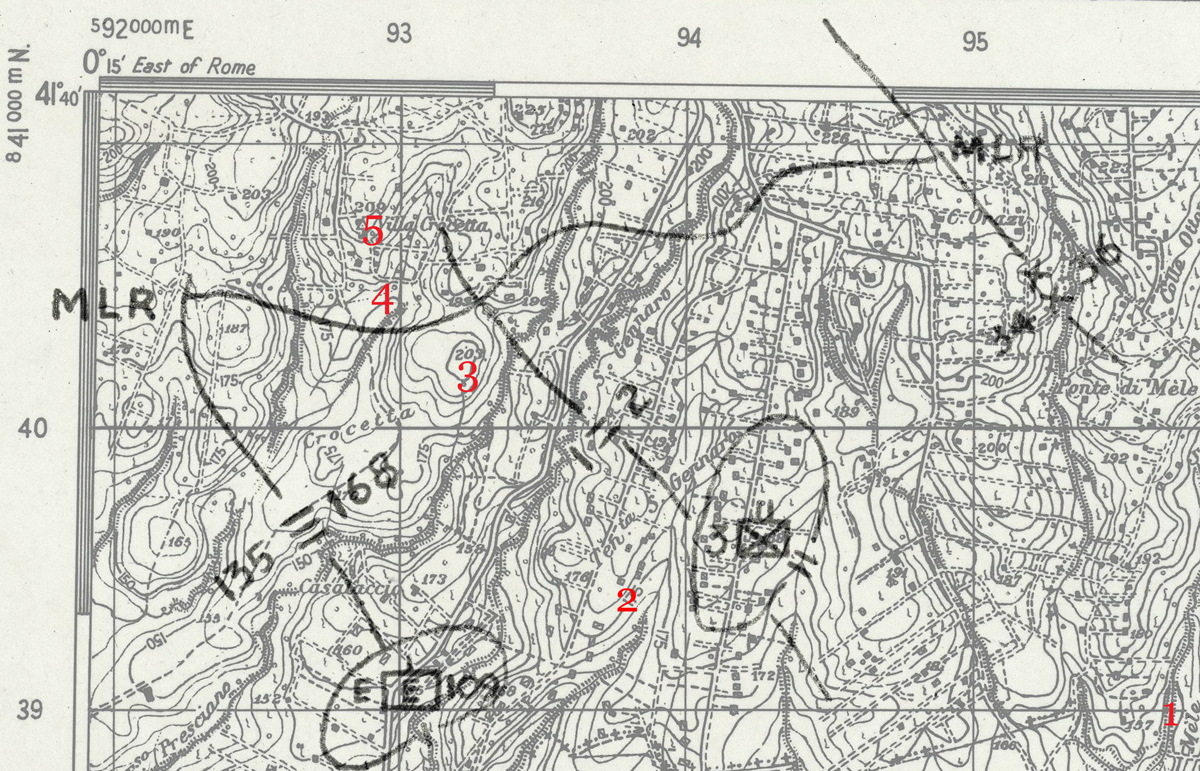

The Fourth Assault on Villa Crocetta

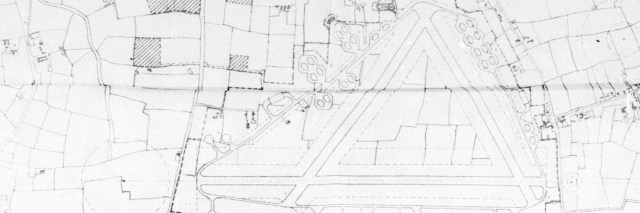

On May 26, 1944, the fourth day of the breakout from Anzio, Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion was assigned to support the 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division during operations against the Caesar Line in the Alban Hills near Lanuvio, Italy. Two days later, 1st Battalion of the 168th Infantry Regiment began a series of unsuccessful assaults on a German stronghold known as Villa Crocetta (located at approximately 41° 39’ 45” N, 12° 42’ 49” E along the present day Via di Colle Crocette, southeast of Lanuvio). The Fifth Army History Part V: The Drive to Rome, summarizing the 168th Infantry Regiment history for May 1944, described the fortifications as follows:

On the right the 168th Infantry faced two particularly nasty strongpoints: Gennaro Hill and Villa Crocetta on the crest of Hill 209. As our troops approached either point, they had to cross open wheat fields on the neighboring hills, then make their way across the draws formed by the tributaries of Presciano Creek, and finally attack up steep slopes to their objectives. The German line was marked by a trench five to six feet deep which ran across Hill 209 and on past the southern slopes of Gennaro Hill. Based on this trench and its accompanying dugouts, machine guns were emplaced to command the draws, and mortars were located in close support. At Hill 209 the enemy also had wire nooses, trip wire, and single-strand barbed wire to break the impact of our charge.

According to the “History of the 168th Infantry Regiment for May 1944,” by the afternoon of May 29, 1944, the men of 1st Battalion were close to exhaustion. They had made two assaults on May 28, 1944, one of which cost the life of a Delawarean, 2nd Lieutenant William B. Weldon, Jr. (1916–1944). A third on the morning of May 29 had also failed. Perhaps the most demoralizing thing was that one attack was going well until they were forced to retreat due to poorly coordinated friendly artillery fire.

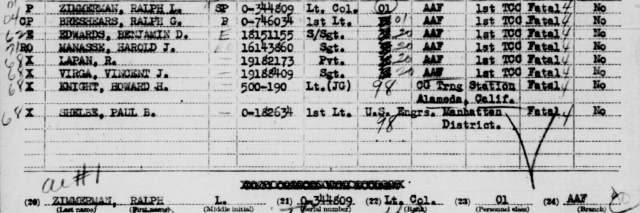

Lieutenant Colonel Wendell H. Langdon (1908–1984) ordered 1st Battalion to make a fourth attack on Villa Crocetta, which began at 1315 hours on May 29, 1944. Unlike the previous three attacks, this one was made with the “support of four M10 tank destroyers and three light tanks” (the latter likely from Company “D,” 191st Tank Battalion). Lieutenant Jarvie’s M10 was one of the tank destroyers. It was his seventh wedding anniversary.

That afternoon, Lieutenant Jarvie shared the turret of his tank destroyer with two men: Sergeant Robert D. Lightsey (1911–1944) and Corporal Elmer F. Park (1919–1944). If his platoon leader had not been aboard, Sergeant Lightsey would have been commanding the M10 and Corporal Park would have served as gunner. Presumably, with his platoon leader aboard, Sergeant Lightsey would have assumed the role of gunner, with Corporal Park moving to the loader’s position. Seated below and to the front of them in the hull of the M10 were the driver, Corporal John F. Perkins (1908–1984), and the assistant driver, Private Reamer H. Conner (1923–1998).

Unbeknownst to the officers planning the assault, German strength was higher than anticipated. According to the 168th Infantry Regiment’s S-3 journal, after the attack the battalion obtained intelligence indicating that the Germans had “8 tanks dug in at Villa Crocetta and a Bn [battalion] in strength defending with a Bn in reserve.” Eight enemy tanks were simply too much for four M10s to reasonably handle.

Compounding matters was the fact that according to the 168th regimental history, “After the failure of the third attack on the Villa, [1st Battalion’s] Company ‘A’ and Company ‘C’ were approaching the point of complete demoralization” and most of them refused to advance. Only Company “B” made any significant headway against the objective.

In a statement reproduced in Lieutenant Jarvie’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F), the M10’s assistant driver, Private Conner, wrote that they had been attacking German infantry when they were notified by radio of an imminent friendly artillery strike. They withdrew and replenished their ammunition supplies from a halftrack commanded by Staff Sergeant West R. Lyon (1916–1988). An officer from 1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment, Captain William W. Galt (1919–1944), was observing the action with Lyon and accompanied the renewed attack.

Conner continued, “We moved up again and we were crossing a ditch and threw a track. We finally got the track on with a bar, Sergeant Lightsey put a new antenna on (broken one was shot off).” At some point—probably after the track was repaired, based on the survivors’ statements—Captain Galt boarded the M10, standing on the rear deck and manning the tank destroyer’s .50 machine gun as they approached German-occupied buildings and trench line. The M10 also destroyed a German antitank gun spotted by an infantryman accompanying the assault, Technical Sergeant Ervin M. Frey (1919–1991).

Private Conner recalled that the M10 advanced through an olive grove and, spotting German soldiers in a trench, they “cleaned up the Infantry[.]” The German infantry took heavy casualties—at least 15 and as many as 80 were killed or wounded, depending on the account.

Then, around 1420 hours, disaster struck. In his 1977 book, Cassino to the Alps, Ernest F. Fisher, Jr., drawing on postwar interviews with German sources, wrote that

the penetration at Villa Crocetta and the earlier abortive thrust [by 2nd Battalion, 168th Infantry] on San Gennaro Hill had hit the Germans at a critical point, along the boundary between the 3d Panzer Grenadier and the 362d Infantry Divisions. Unless quickly contained, the thrusts might develop into a breakthrough of the Caesar Line southeast of Lanuvio. To forestall such a blow, [General Alfred] Schlemm, the I Parachute Corps commander, ordered the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division, the stronger of the two German units to counterattack […] Spearheaded by a rifle company, supported by four self-propelled guns[.]

According to the contemporary 168th Infantry history, the 1st Battalion intelligence officer observed

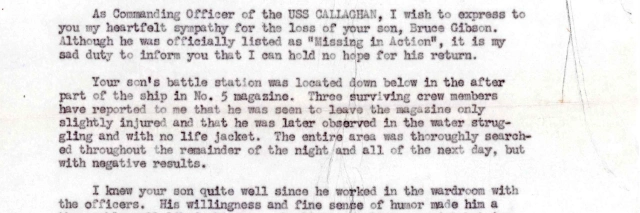

an estimated company of Germans, supported by four tanks, counter-attacking down the valley with bayonets fixed. One of the tanks pulled up behind the Villa and fired a shell through the turret of a tank destroyer, killing the battalion operations officer who had been firing the tank destroyer’s 50 callibre [sic] machine gun at the retreating Germans.

In a statement reproduced in Lieutenant Jarvie’s I.D.P.F., Corporal Perkins recalled that

After we picked up this Infantry Captain, we travelled about one hundred (100) yards before we were hit. The Captain was standing on the back of the Tank Destroyer when he got killed. He was firing the .50 caliber. We were sitting still when the tank [sic] was hit. The shell came through the turret. I saw Lt. Jarvie and Sergeant Lightsey fall to the bottom of the turret. In about four or five seconds, the tank caught fire and I went out the turret on the left side after crawling over them (both of them). I’m certain that they were both dead.

Private Conner recalled that he was initially unaware that the M10 had been hit:

I thought it was a .50 caliber shooting in our turret at first. As the hot lead sprayed around, Corporal Perkins shouted that he was hit and told us to get out. I jumped out when it blazed on the Ass’t. drivers side. I went out the turret and started running. Perkins stopped me and put the fire out in my hair. Then we crept, crawled, and ran to get into a ditch. Then we crawled over a small hill to where the Infantry was in a wheatfield and then to the next wadi where the medic was. I don’t remember feeling anything. I had my eyes closed because it was blazing there and I didn’t want them burnt.

The 168th Infantry Regiment history ruefully noted that the German “counter-attack, supported by tanks, was too strong for the twenty men left to hold the hill.” The surviving American infantry retreated.

It’s not clear if the same German shell that killed Lieutenant Jarvie and Sergeant Lightsey also claimed the lives of Corporal Park and Captain Galt (whose bodies were located next to the burned out M10), but Corporal Perkins and Private Conner were the only survivors of the crew. Corporal Perkins later told his family that he and Conner hid from the Germans for a time—close enough to them laughing—before they were able to escape back to American lines.

Aftermath & Repatriation

Private Conner was hospitalized for wounds to his head as well as his hands, and Corporal Perkins for wounds to his thoracic wall and hands. Both men were hospitalized until July 1944. After they were discharged from the hospital, both men rejoined the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion and continued to serve through V-E Day. Captain Galt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. It appears that the members of the M10 crew received no decorations for their actions fighting alongside him other than the Purple Heart.

The War Department was slow to supply Lieutenant Jarvie and Sergeant Lightsey’s families with information. By October 16, 1944, the U.S. Army had a sworn statement from Corporal Perkins that he was certain both men were dead, but that alone was not sufficient grounds to change their status from missing in action to killed in action. Desperate for more information, Jarvie’s sister-in-law, Helen Webb Jarvie (1912–1998, wife of John’s brother, Walter), wrote John’s former company commander, Captain Baker D. Newton on November 2, 1944:

The War Department says he disappeared May 29th but that is the last we have heard. John’s mother is living with us & she as well as the rest [of] us are more than anxious about him. Do you think it is possible he may have been taken prisoner? Don’t hesitate to tell me what you really think about it, because I’ve almost given up hope. If he had been taken prisoner I think we would have heard by this time.

Lieutenant Jarvie and Sergeant Lightsey’s remains, initially referred to as Subject Deceased Unknown 53531 (later as Unknown X-663), were buried at the U.S. Military Cemetery Nettuno, Italy, on December 12, 1944, and had been tentatively identified by December 16, 1944. Even so, their status was not changed for another three months. The Trenton Evening Times reported Lieutenant Jarvie’s death on February 26, 1945.

On December 21, 1945, Bertha May Koller Jarvie remarried at 351 Centre Street to Harry Warren Errickson, Jr. (1909–1986), with whom she raised one son.

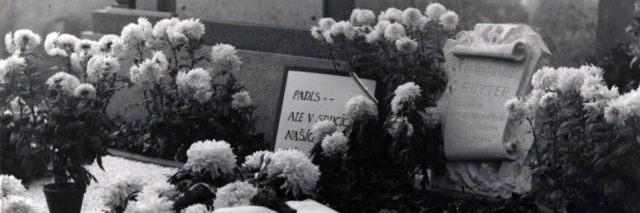

After the war, Jarvie and Lightsey’s remains were reburied at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 34, Grave 4845) on January 17, 1950.

One detail not mentioned in Corporal Perkins’s statement was the fact that, as he escaped the burning tank destroyer, he grabbed an identification bracelet that Lieutenant Jarvie was wearing. Such bracelets were commonly purchased privately and worn by servicemembers in addition to their military-issued dog tags. Although Perkins told his family that he had hoped to return the bracelet to Jarvie’s family, he was unable to do so during his lifetime.

In 2008, April Anderson Padgett—Corporal Perkins’s grandson’s wife—began an effort to locate Jarvie’s family. She started telephoning people in the Trenton area with the last name of Jarvie but did not reach anyone from the right family. In May 2015, she made a Facebook post about the story which included a photograph of the bracelet. She encouraged others to share it, and eventually over 2,000 people did. More than a year later, in July 2016, the post finally reached one of Lieutenant Jarvie’s great-nephews. He contacted her and arranged for the bracelet’s return to the family.

1st Lieutenant Jarvie is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware, along with other servicemembers from Delaware and New Jersey who lost their lives during World War II and the Korean War.

Notes

Other Articles About Lieutenant Jarvie

This piece is the culmination of nearly five years of research. Previously published pieces involving Jarvie include: 1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie: Jack in the Alice Griffin Letters, which focuses on the process of identifying him in a wonderful series of letters written by a nurse who served with my grandfather; Jarvie, John S. (894th), a medium-length profile for TankDestroyer.net; and John Scott Jarvie, a short piece for Fold3 as part of the Stories Behind the Stars project.

Mother’s Name

Some sources list Daisy Olive Jarvie’s maiden name as Johnson, but it appears this was anglicized after she immigrated from Sweden. An Ancestry.com family tree gives her original name as Dagny Olivia Jonasson. Her first name was also spelled Daisey.

Commissioning

Newspaper articles about Jarvie do not mention any prewar service. There is no known U.S. Army enlistment data card for him, though about 15% are missing or could not be successfully digitized. This raises the possibility that he was directly commissioned on April 3, 1942. Although direct commissions did happen in various cases, such as doctors or dentists, it seems unlikely that graduating from a military high school alone would have qualified him. Still, circumstantial evidence suggests Jarvie was an enlisted man at some point. If so, he may have attended Officer Candidate School (O.C.S.) at Fort Benning, Georgia. Whether he attended O.C.S. or not, wherever he was commissioned must have been within a few hours’ travel distance from Fort Bragg, where he was attached for rations the following day.

Campoleone Salient

Newspaper accounts about the incident in which Lieutenant Jarvie was trapped behind enemy lines are confusing and contradictory about how many vehicles were trapped. Daniel De Luce wrote that only two tank destroyers were trapped. One explanation for the discrepancy could be that he intended to write that two or three platoons were caught behind enemy lines, including those under the command of Jarvie and Lieutenant Herbert M. Siercks (1916–1986).

A third article written about the exploits of Company “C”—this one by Reynolds Packard (1903–1976) on February 5, 1944—also described how a platoon which included Staff Sergeant John Shoun (1920–2002) “broke through the German ring of tanks and infantry”—so it seems that more than two M10s from the company escaped encirclement that night.

Headstones

Jarvie and Lightsey have had three headstones at Arlington National Cemetery over the years. Their original headstone listed their names, date of death, and that they were Infantry branch. By June 19, 2021, that headstone had been replaced by one which mentioned they were killed at Lanuvio but which added inaccurate dates of birth for both men. I notified Arlington of the discrepancy that day, provided both men’s birth certificates, and a new headstone with the correct dates of birth was installed in less than six months.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Jarvie, Newton, Padgett, Feeney, and Uhler families for contributing photos and information that were vital in telling Lieutenant Jarvie’s story. Thanks also go out to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for obtaining a copy of Lieutenant Jarvie’s officer’s pay card.

Bibliography

“87 Pass Exams for Trenton Police Jobs, 85 for Firemen.” Trenton Evening Times, March 28, 1940.

“Albert Jarvie.” The Montclair Times, March 22, 1938. https://www.newspapers.com/article/148234093/

“Arlington Burial For Lieut. Jarvie.” Trenton Evening Times, January 19, 1950.

Baldy, Paul A. “S-3 Periodic Report From:31800A Feb.44 To: 41800A Feb.44.” February 4, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Bigart, Homer. “Anzio Area Good for Tanks, Better for Tank Destroyers.” Wilmington Morning News, February 7, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/148297940/

Certificate and Record of Birth for John Scott Jarvie. November 16, 1914. New Jersey State Archives, Trenton, New Jersey.

De Luce, Daniel. “Yanks Save British in Nazi Tank Push.” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, February 6, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/40312608/

Draft Registration Card for Philip Henry Jarvie. February 16, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for New Jersey, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44025_03_00036-02761

Draft Registration Card for Albert Louis Jarvie. September 12, 1918. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005266931_05722

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4660918_00728

Fifth Army History Part V: The Drive to Rome. Publisher unknown. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/5th-army-history-part-v-chapter-vii.pdf

Fisher, Ernest F., Jr. Cassino to the Alps. Originally published in 1977, republished by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1993. https://history.army.mil/html/books/006/6-4-1/CMH_Pub_6-4-1.pdf

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4383793_00578

“The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment from May 1, 1944 to May 31, 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/168th-infantry-regiment-history-may-1944.pdf

Individual Deceased Personnel File for John S. Jarvie. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Robert D. Lightsey. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Interment in the Arlington National Cemetery Control Form for John S. Jarvie. February 7, 1950. Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_2321306652_0459-02512

Jarvie, Helen Webb. Letter to Baker D. Newton, November 2, 1944. Courtesy of the Newton family.

“Lieut. Jarvie Killed; Was Listed Missing.” Trenton Evening Times, February 26, 1945.

“Lt. Jarvie, of Trenton, Tank Destroyer Hero.” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, February 6, 1944.

Marriages March, 1936 – May, 1954 St. Michael’s Church Trenton, N. J. Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/62073/images/62073_302022005552_0423-00078

Morning reports for Company “A,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. April 1942 – September 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Morning reports for Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. April 1942 – June 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Morning reports for Headquarters Company, 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. April 1942 – February 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Newton, Baker D. Letter to the Newton family, May 17, 1943. Courtesy of the Newton family.

Newton, Baker D. Letter to the Newton family, September 12, 1943. Courtesy of the Newton family.

Officer Pay Card for John S. Jarvie. Army Officers Pay Cards, 1940–1951. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

Packard, Reynolds. “Tank Platoon Mauls Enemy.” The Charlotte Observer, February 6, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/47260697/

Report of Marriage for Harry Warren Errickson Jr and Bertha May Koller Jarvie. December 21, 1945. Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey Church Records, 1700–1970. Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey, Trenton, New Jersey. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/62073/images/62073_302022005552_0429-00474

Report of Marriage for John S. Jarvie and Bertha May Koller. May 29, 1937. Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey Church Records, 1700–1970. Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey, Trenton, New Jersey. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/62073/images/62073_302022005552_0429-00318

Silverman, Lowell. “1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie: Jack in the Alice Griffin Letters.” 32nd Station Hospital website. March 25, 2020, updated May 28, 2024. https://32ndstationhospital.com/2020/03/25/1st-lieutenant-john-s-jarvie-jack-in-the-alice-griffin-letters/

Silverman, Lowell. “Captain William W. Galt: ‘Always Out In Front’.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society website. May 29, 2021. https://www.cmohs.org/news-events/medal-of-honor-recipient-profile/captain-william-w-galt-always-out-in-front/

Silverman, Lowell. “Sergeant Robert D. Lightsey (1911–1944).” Delaware’s World War II Fallen website. December 28, 2021, updated May 28, 2024. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2021/12/28/sergeant-robert-d-lightsey/

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02357-00259, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02434-00511

“Trentonians In Line for Jobs.” Trenton Evening Times, August 11, 1938.

Last updated on May 29, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.