| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Usher for Ace Theatre, worker at Allied Kid Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32952342 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Company “F,” 145th Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Distinguished Service Cross, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge | Luzon campaign (1945) |

Early Life & Family

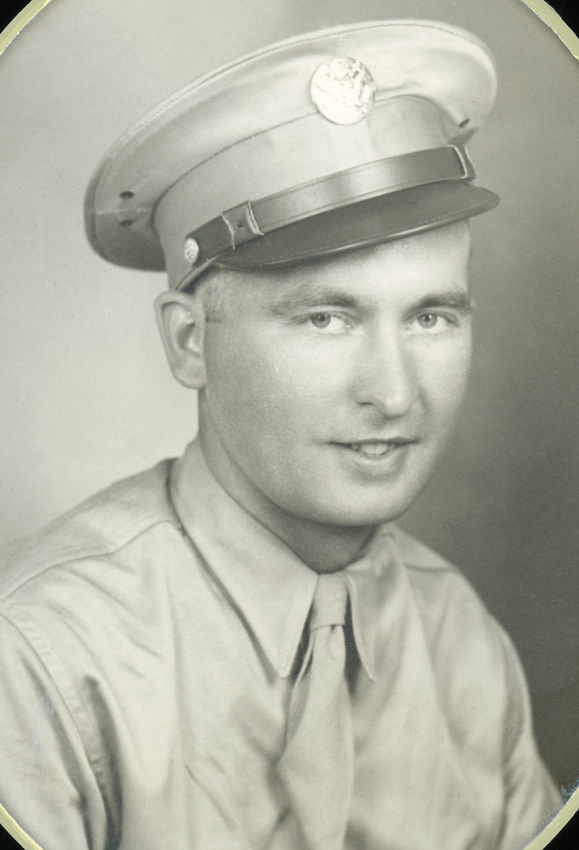

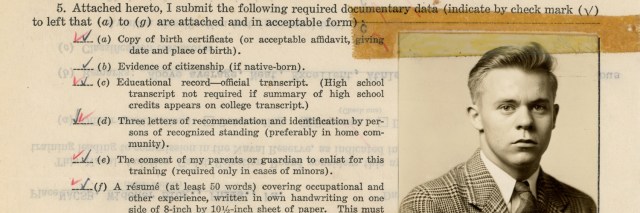

Joseph Frank Maczynski was born at 423 8th Avenue in Wilmington, Delaware, on the morning of May 25, 1920. He was the son of Frank Maczynski (also spelled Muncznski or Monczinski, c. 1880–1943) and Mary Maczynski (née Baczkowski, c. 1891–1945). His father’s occupation was described in various records over the years as laborer, furnace worker at a car wheel shop, iron worker, and mechanic. Both of his parents were Polish immigrants born in the Russian Empire. He had three older sisters, an older brother, and two younger brothers. Two of his brothers both served in the U.S. Army during World War II.

Maczynski, his parents and four siblings were recorded on the census in April 1930, living at 111 Bird Street in Wilmington. His father was listed as a furnace worker at a car wheel shop. At the time of the next census in April 1940, Maczynski was living with his parents and brothers at the same address, while working as an usher at the Ace Theatre. He was living and working at the same locations when he registered for the draft on July 1, 1941. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, 10 inches tall and weighing 145 lbs., with blond hair and blue eyes.

Census records indicate Maczynski dropped out of school after completing the 8th grade. He was Catholic.

The Wilmington Morning News stated that Maczynski “joined the Army in July, 1943, while employed at the Allied Kid Company. Previously he had worked at the Ace Theatre.” Curiously, his enlistment data card better describes the theater job, describing Maczynski as a recreation and amusement attendant.

Military Training

After he was drafted, Maczynski was inducted into the U.S. Army in Camden, New Jersey, on June 21, 1943. No details about Private Maczynski’s stateside training are available. A few months into his military service, on December 27, 1943, his father died in the Delaware Hospital in Wilmington from a ruptured blood vessel in his heart. It is unclear if Maczynski was able to obtain a furlough to attend the funeral.

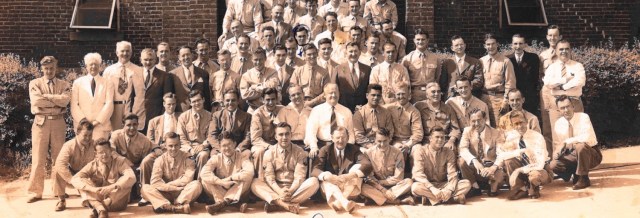

Private Maczynski went overseas as a replacement around February 1944. By April 7, 1944, Maczynski was with the 6th Replacement Depot on New Caledonia. That day, he was transferred to the 37th Infantry Division. On April 15, 1944, Maczynski and 18 other replacements joined Company “F,” 145th Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Division, on Bougainville. His unit had fought in the New Georgia and Bougainville campaigns.

Company “F” had particularly distinguished itself during the March 1944 fighting on Bougainville, suffering severe casualties during the fighting at Hill 700. Maczynski was among the replacements for those casualties. Although Allied forces had not captured the entire island, the beachhead and airfields had been secured and the remaining Japanese forces were no longer a serious threat to the perimeter.

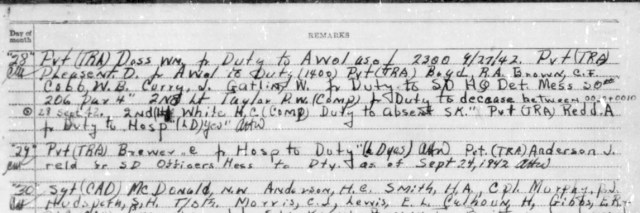

Private Maczynski was assigned to 4th Platoon (Weapons Platoon), Company “F.” He injured his left arm in an accident on July 8, 1944, and was treated at the 112th Medical Battalion clearing station. Morning reports stated that he suffered a fracture, but it must have been minor since he returned to duty five days later. He was promoted to private 1st class sometime between July 13, 1944, and January 26, 1945.

A regimental history stated that from July to September 1944, the 145th Infantry “was on the line, occupying defensive positions protecting the beachhead at Empress Augusta Bay, Bougainville Island.” Since there were only occasional skirmishes with the Japanese forces on the island, “The Regiment underwent a program of ‘progressive training,’ emphasizing squad and platoon culminating in assault training.” An operations report added: “Intensive training in amphibious operations, all types of open terrain warfare, assault of fortified positions, combat – in – towns, and tank – infantry operations were conducted during August to November, 1944.”

On November 17, 1944, the 145th Infantry went into staging prior to shipping out to participate in the liberation of the Philippine Islands. On December 11, 1944, 2nd Battalion, including Maczynski’s Company “F,” boarded the transport U.S.S. Starlight (AP-175). The ship joined a convoy departing Empress Augusta Bay on December 16, 1944. After several practice amphibious landings, the convoy continued to Manus Island, arriving on December 21. 10 days later, Starlight and the other ships sailed for the Philippines.

The Luzon Campaign

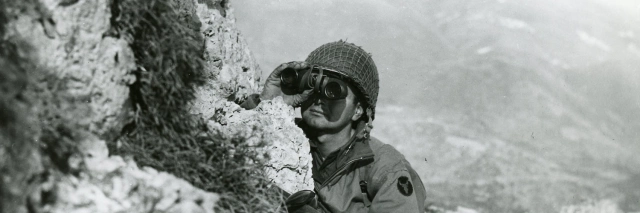

Private 1st Class Maczynski’s convoy arrived in Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, on the morning of January 9, 1945. Just over three years earlier, the gulf had been the site of the principal Japanese landings in the Philippines during their invasion in the dark days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Initially most of the 145th Infantry, including Company “F,” remained in reserve, though 2nd Battalion landed on January 10, 1945. In subsequent days, the regiment advanced south, encountering virtually no opposition for over two weeks. On January 26, 1945, 2nd Battalion led the regiment in an assault as American forces began to retake Clark Field. Private 1st Class Maczynski was awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge effective that day, per General Orders No. 4, Headquarters 145th Infantry Regiment, dated February 13, 1945.

The following morning, January 27, 1945, 2nd Battalion repulsed an attack by enemy infantry and then pressed forward to take Angeles. The battalion was relieved by the 148th Infantry Regiment and went into reserve on January 29. The battalion moved several times during subsequent days, as American forces continued south toward Manila. Although there was limited Japanese resistance, 145th Infantry’s advance was slowed by the enemy’s destruction of bridges over several rivers. Despite the obstacles, they reached the northern outskirts of Manila.

Although the Japanese commander in the Philippines, General Yamashita Tomoyuki (1885–1946), had ordered his forces to withdraw from Manila, one of his subordinates, Rear Admiral Iwabuchi Sanji (1895–1945), disobeyed his orders. The stage was set for one of the greatest tragedies of the Pacific War. Admiral Iwabuchi’s men would force the Americans to fight for every block. Over 100,000 Filipino civilians were murdered by the Japanese or killed in the crossfire during a month of ferocious combat. Manila, the “Pearl of the Orient,” was largely reduced to ruins.

At 0135 hours on February 4, 1945, 2nd Battalion continued their advance south, reaching Banga at 0805 hours. They continued south to Malinta. At a nearby crossroads, Japanese resistance stiffened, and the battalion was ordered to hold its position. 2nd Battalion repulsed several counterattacks before reinforcements from 3rd Battalion arrived to break the deadlock that night.

Private 1st Class Maczynski and his comrades had little time to rest. The regimental operations report stated that on February 5, 1945, “Shortly after midnight the 2nd Battalion started moving to Manila with the mission of securing the Pasig River on the right flank of the regimental sector.”

The battalion advanced into the Tondo district of Manila, where “civilians reported that the enemy was strongly entrenched in the vicinity of Tondo Church and the Philippine Manufacturing Company.” To advance further, the battalion had to cross a canal, Estero de la Reina. The operations report continued:

While crossing the Estero De La Reina the battalion received heavy fire from the vicinity of these two points. The firefight continued all day and when evening came the battalion was still two city blocks north of the Church and Factory. At 2100I, the enemy started fires and set off demolitions forcing the battalion to withdraw to the north [sic] side of the Estero again.

The fighting in Manila during the period was continuous and heavy. All units received artillery, mortar, machine gun, and rifle fire throughout the day. Enemy demolition crews were especially active and as a result of their work a large portion of the Tondo District lay in ruins the following morning.

On February 6, 1945, facing lighter resistance, 1st and 2nd Battalions continued advancing south towards the Pasig River. The following day, 1st and 2nd Battalions extended their lines east along the north bank of the river, relieving elements of the 148th Infantry Regiment and 1st Cavalry Division. The Japanese continued to hold out on the Tondo Peninsula.

On the morning of February 8, 1945, 2nd Battalion pushed into the Tondo Peninsula with artillery plastering enemy strongpoints discovered in their path. The regimental operations report stated:

Enemy fire was heavy and resistance stubborn. During the afternoon, the enemy attempted to land reinforcements from barges in the North Harbor area. Approximately twenty (20) enemy riflemen were discharged before the barges were destroyed, but they were quickly disposed of by Company F.

That evening, most of 2nd Battalion was relieved, except for two platoons each from Companies “F” and “G” which continued mopping up the peninsula. With the north bank of the river secure, on February 10, 1945, most of 2nd Battalion, including Company “F,” moved north back to Malinta. They would have to deal with nearby Japanese forces bypassed during the drive on Manila.

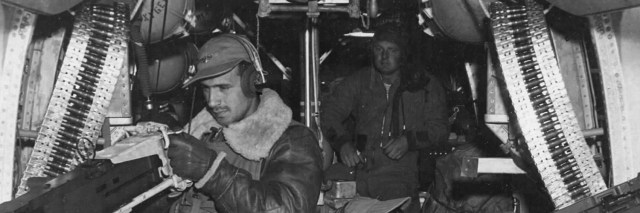

As of February 12, 1945, Private 1st Class Maczynski was serving as an ammunition bearer in 1st Squad, Machine Gun Section, 4th Platoon, Company “F,” 145th Infantry Regiment. The regimental operations report stated:

At 0800I, the 2d Battalion, supported by one (1) platoon of medium tanks, M-7s from the Cannon Company, and 4.2″ mortars, was ordered to make an assault crossing the Binuangan River in the vicinity of Pasolo with the mission of destroying all enemy forces in the Dampalit area.

The terrain was difficult to traverse. The town of Dampalit was on a strip of dry land essentially surrounded by a lagoon converted to shallow fishponds. Though the term “river” suggests dry ground on either side, in this area, rivers were simply deeper channels through the fishponds. The enemy occupied Dampalit and dikes nearby.

Around 0930 hours that morning, Company “F” crossed the Binuangan River. Maczynski’s platoon leader, 1st Lieutenant Bernard L. Patterson (1919–2008), later recounted in a statement:

The 1st squad took up a firing position to cover our advance toward Dampalit after our crossing of the Binuangan River was successful. The route of approach to this position was across an area of fish ponds and it was necessary to move forward to the gun position through waist-deep water and mud. The Japanese positions in the edge of the row of trees and houses at Dampalit were well concealed and strongly held. For the attack to succeed it had to have a great volume of fire placed on those positions. Private First Class Maczynski left the ammunition that he was carrying at the gun position and immediately went to the ammunition dump for a resupply of ammunition. Several men had been wounded on the route that he had to take but without any hesitation on his part I saw him make two trips to the ammunition dump and return to the gun. Each time he drew fire from the Japanese positions.

Another eyewitness, 1st Lieutenant Clinton S. McLaughlin (1916–1971), added:

The terrain was open and the enemy’s observation was excellent. All movement was very slow due to the mud and so allowed the enemy riflemen excellent chances for observed fire. The enemy positions were strongly defended, well concealed and dug in along the edge of a row of trees and wrecked houses. These positions were approximately 200 yards from the route traveled by Private Frist Class Maczynski.

Maczynski’s squad leader, Sergeant Chester L. Shawver (1923–1999), later recalled:

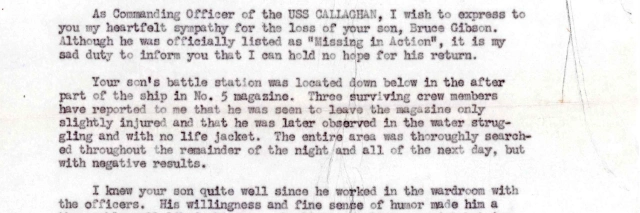

He knew that already our company had three men hit along the route that he had to take. In spite of this he did not hesitate but made two complete trips up with ammunition. Although he was completely exhausted from making the 300 yard trip through the mud and water, Private First Class Maczynski started to the rear a third time but about 50 yards to the rear of the gun position he was killed instantly.

Lieutenant Patterson added:

On his third attempt he was shot through the head and died instantly. His courage and selfsacrifice [sic] has been an everpresent reminder to the men of his squad and his platoon of what one man can do. His services prior to his death had been very good and it was the ammunition that Private First Class Maczynski brought forward that day that played a great part in the success of the company’s attack.

By February 13, 1945, the day Maczynski was buried at U.S. Armed Forces Cemetery Manila No. 1, 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 145th Infantry had defeated the bulk of Japanese forces in the area of Dampalit and Binuangan. They spent the next few days mopping up before rejoining the Battle of Manila. During February 11–14, 1945, Company “F” sustained a total of seven dead, including Maczynski, and at least 22 men wounded in action.

In a memorandum dated April 27, 1945, the regimental commander, Colonel Cecil B. Whitcome, nominated Private 1st Class Maczynski for the Distinguished Service Cross. In a ceremony on November 4, 1945, Fort DuPont’s commanding officer presented the medal to Maczynski’s older sister, Josephine Zlock (1913–1979), at a ceremony broadcast on WDEL. Maczynski’s mother was already in poor health when Private 1st Class Maczynski was killed. She died shortly after the award presentation, on December 15, 1945.

In addition to the Distinguished Service Cross, Private 1st Class Maczynski’s awards include the Purple Heart, the Combat Infantryman Badge, and the Philippine Liberation Ribbon.

In 1947, Maczynski’s sister, Josephine, requested that his body be repatriated to the United States. On November 13, 1947, Maczynski was temporarily reinterred at the Army Graves Registration Service Mausoleum, Manila. In late 1948, his casket was transferred to the U.S.A.T. Sgt. Jack J. Pendleton, arriving at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation in January 1949.

On February 11, 1949, Corporal Robert R. Conway accompanied the body from Jersey City, New Jersey, to Wilmington by train. Following requiem mass at St. Hedwig’s Roman Catholic Church on February 14, 1949, Private 1st Class Maczynski was buried alongside his parents at Cathedral Cemetery in Wilmington. He is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Father’s Age

Discrepancies in date of birth are common among immigrants from Eastern Europe prior to World War II, but Frank Maczynski’s is especially inconsistent in different records. His headstone stated he was born in 1870, while his death certificate gave his date of birth as September 10, 1880. The 1920 census indicates he was born around 1875, immigrated in 1890, and was naturalized in 1895. The 1930 census placed his year of birth as around 1879, while the 1940 census suggested he was born in 1888!

Older Sisters

Although his birth certificate describes him as his parents’ fifth child, there are discrepancies about Maczynski’s biological relationship to his oldest two sisters. If census records are reliable, they were born before his mother’s immigration to the United States. Helen Bisio (1909–1937) died before the war, while his eldest sister, Stella Saragino (1907–1966), was described as his stepsister by the Wilmington Morning News in 1945 and not mentioned in other newspaper articles at all.

His older sister, Josephine Zlock, who also accepted her brother’s Distinguished Service Cross on behalf of her family, described herself as Maczynski’s oldest sibling in an April 1, 1948, letter to the War Department, albeit in rather ambiguous terms: “I am the oldest one which I will take care of the remains of my Brother Joseph F. Maczynski so please, you will find both my parents death certificates which I am sending.”

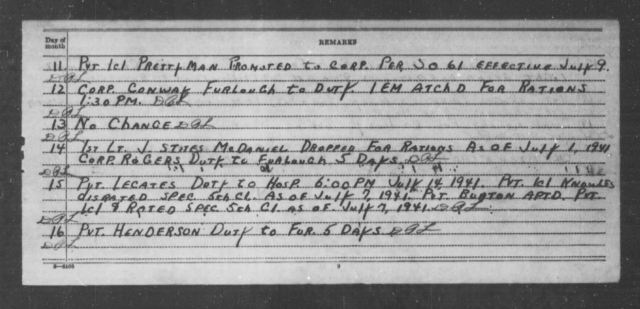

Military Occupational Specialty

Curiously, a unit morning report listed Maczynski’s military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code as 745. Although 745 could be associated with multiple titles, rifleman was the most common. Under Table of Organization No. 7-17, the only 745s in Weapons Platoon of Company “F” should have been messengers. However, multiple statements describe Private 1st Class Maczynski as an ammunition bearer, which normally would have had the M.O.S. code of 604.

Another Delawarean, Private Robert D. Henderson (1923–1944), a member of 4th Platoon, Company “K,” 333rd Infantry Regiment, 84th Infantry Division, was also listed in a morning report with M.O.S. code 745, despite testimony from one of his friends that he was a member of a machine gun squad.

Discrepancies between M.O.S. codes listed in morning reports and what should have been authorized by the tables of organization are not uncommon. Discrepancies are also fairly common between M.O.S. codes and other sources in regard to what a soldier did. In some cases, a soldier held one M.O.S. while being assigned another duty. Sometimes a morning report specified both, sometimes one, and sometimes neither. Thus, it is possible that Maczynski held the M.O.S. of rifleman or messenger but when assigned to the light machine gun section, performed the duty of ammunition bearer.

Not every discrepancy can be explained in such a fashion, of course, and it would be puzzling that Maczynski would not be reclassified if he was performing that duty for an extended time.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Private 1st Class Maczynski’s nephew, Joe Maczynski, and to Matt LeMasters for providing documents, photos, and information that were invaluable in telling this story.

Bibliography

“7 Posthumous Combat Medals Given State Men in Broadcast.” Journal-Every Evening, November 5, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/135701335/

“145th Infantry Luzon Campaign S-3 Operations Narrative.” Undated, c. 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Application for Headstone or Marker for Joseph F. Maczynski. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_1521003240_0429-00091

“Bernard L. Patterson, MD.” The News & Observer, September 30, 2008. https://www.newspapers.com/article/145193098/

Certificate of Birth for Joseph Maczynski. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6GVS-K7W

Certificate of Death for Frank Maczynski (Monczinski). Delaware Death Records. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMB-L914-K

“Chester Lee ‘Chet’ Shawver.” The Idaho Statesman, August 25, 1999. https://www.newspapers.com/article/145189431/

“Clinton Sebastian McLaughlin.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/140592477/clinton-sebastian-mclaughlin

Draft Registration Card for Joseph Frank Maczynski. July 1, 1941. WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_04_00006-00609

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531892_00313

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4295770-01035

“General Orders Number 4.” Headquarters 145th Infantry Regiment, February 13, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“General Orders Number 26.” Headquarters 145th Infantry Regiment, February 13, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Joseph F. Maczynski. Army Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1942–1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Morning reports for Company “F,” 145th Infantry Regiment. April 1944 – February 1945. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Matt LeMasters.

“Pfc. Joseph F. Maczynski.” Journal-Every Evening, February 10, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/article/135701704/

“Regimental History.” Headquarters 145th Infantry Regiment, October 1, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00552-00213

“Table of Organization and Equipment No. 7-17: Infantry Rifle Company.” War Department, February 26, 1944. Military Research Service website. http://www.militaryresearch.org/7-17%2026Feb44.pdf

U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/701380961/maczynski-joseph-f-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32952342&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3448586

Last updated on May 11, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.