| Home State | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware | Automotive mechanic/gas station attendant |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Marine Corps | 341238 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Company “L,” 3rd Marines, 3rd Marine Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Bougainville, Guam |

| Military Occupational Specialty | |

| 653 (squad leader) |

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my previous articles about Sergeant Caulk’s brother, Seaman 2nd Class Charles L. Caulk, Jr., and 1st Lieutenant Ferris L. Wharton, who was also killed in action on Guam.

Early Life & Family

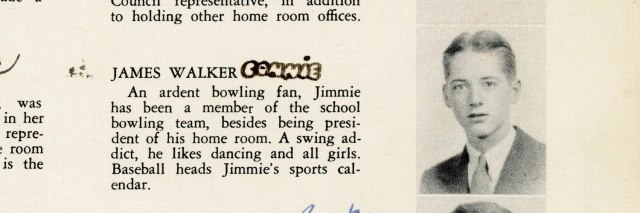

Paul Lee Caulk was born on June 15, 1919 at 2203 West 6th Street in Wilmington, Delaware. He was youngest child of Charles Leonard Caulk, Sr. (a switchman for a telephone company, 1886–1948) and Henriette (Hetty) Caulk (née Jacobs, 1891–1981). He had an older brother, Charles Leonard Caulk, Jr. (1913–1942). He also had two older sisters, Rose Marie Caulk (later Van Meter, 1915–1970) and Helen Veronica Caulk (later Abernethy, 1917–1971). Caulk was Catholic.

On July 14, 1922, Caulk’s parents purchased a home at 2137 Linden Street in Wilmington’s Union Park Gardens neighborhood, where he lived until he joined the military. Caulk played football and baseball in high school. He graduated from Wilmington High School in 1937. He also attended a trade school—Fletcher-Brown Vocational School in Wilmington—to become an auto mechanic, graduating in 1939. A 1940 Wilmington city directory listed his occupation as a helper for the Automotive Service Company.

When Caulk registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, he was working for Thomas Davey at a Sun Oil (Sunoco) gas station. The work history in his Marine Corps record stated he was an automobile serviceman or mechanic there, earning $24 or $25 per week (equivalent to about $417–$434 a week or $21,684–$22,568 per year in today’s money). He also spent about a year working as an inspector at a brewery.

Stateside Service

Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Paul L. Caulk volunteered for the U.S. Marine Corps. He enlisted at the Naval Receiving Station, Philadelphia on December 24, 1941. At the time, Caulk was described at the time as standing five feet, 10½ inches tall and weighing 165 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. That same day, he left Philadelphia by train, bound for boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina. Upon arrival on Christmas Day, he joined the 7th Recruit Battalion.

After completing boot camp, Private Caulk was assigned to the Guard Company at the Naval Air Station, Jacksonville, Florida, joining that unit on February 17, 1942. Caulk was promoted to private 1st class on September 24, 1942. In January 1943, Private 1st Class Caulk learned that his brother, Seaman 2nd Class Charles L. Caulk, Jr., was missing in action. Paul Caulk was promoted to corporal on March 16, 1943 (with a date of rank of March 12, 1943).

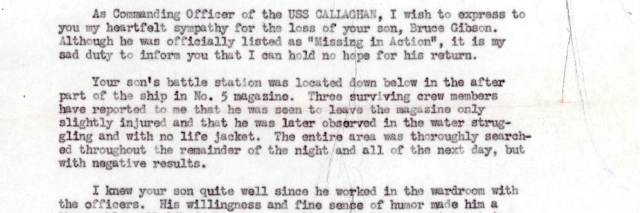

The loss of his brother undoubtably weighed on Corporal Caulk’s mind when he sat for an interview on April 16, 1943 for classification purposes. He expressed his desire to become a pilot. It was his second choice, assignment to the Fleet Marine Force, that the Marine Corps granted. Shortly before this transfer went through, the Caulk family received a letter dated July 19, 1943, stating that U.S. Navy had concluded that Seaman 2nd Class Caulk had been killed in action.

On July 26, 1943, Corporal Caulk transferred to the 21st Replacement Battalion at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. On August 1, 1943, the battalion headed west by train, arriving in San Diego five days later.

The Bougainville Campaign

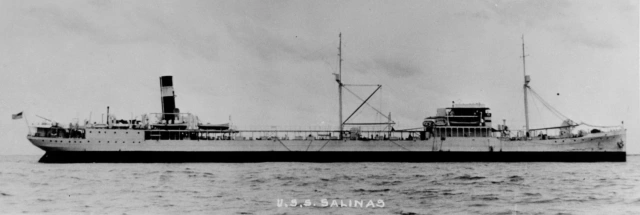

Corporal Caulk boarded the U.S.S. George F. Elliott (AP-105) in San Diego on the afternoon of October 2, 1943. The transport set sail for the Pacific Theater at 0847 hours the following day. The ship crossed the equator on October 11, 1943. Caulk presumably participated in a ceremony that day, since his Marine Corps service record included a stamp from the ship certifying him as a “Shellback.”

The George F. Elliott dropped anchor at Nouméa, New Caledonia at 0952 hours on October 20, 1943; that day, the battalion was attached to the Transient Center, I Marine Amphibious Corps. Corporal Caulk joined the 3rd Marine Division (rear echelon) at Guadalcanal on November 22, 1943. He boarded a Landing Ship, Tank (L.S.T.) on November 24, 1943. The vessel set sail two days later and arrived at Empress August Bay, Bougainville on November 28.

The Bougainville campaign was a continuation of the Allied offensive in the Solomon Islands that had begun at Guadalcanal in August 1942. Guadalcanal had been secured after months of ferocious combat. The casualties included Corporal Caulk’s brother, Seaman 2nd Class Charles L. Caulk, Jr., killed when the light cruiser U.S.S. Juneau was torpedoed on November 13, 1942. After the victory at Guadalcanal, the Allies advanced into the Central and Northern Solomons. Taking Bougainville was an intermediate step in the objective of neutralizing Rabaul, the principal Japanese base in the South Pacific. American troops landed at Empress Augusta Bay on November 1, 1943.

Corporal Caulk was assigned to Company “L,” 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division. The Bougainville campaign was the first time that the 3rd Marine Regiment had been in combat; at the time Caulk arrived on Bougainville, the regiment had just participated in the Battle of Piva Forks.

It is unclear if Corporal Caulk saw any combat on Bougainville; his battalion saw little action after the Battle of Piva Forks. On Christmas Day, 1943 Company “L” shipped out from Bougainville aboard the attack transport U.S.S. Fuller (APA-7), arriving back at Guadalcanal on December 27. American commanders were satisfied with the establishment of a perimeter around airfields that brought Rabaul within range. They shifted most resources elsewhere, though combat continued (first with American and later Australian troops fighting against remaining Japanese forces) until the very end of the war in 1945.

Combat on Guam

Caulk was promoted to sergeant on February 15, 1944. Shortly thereafter, on April 17, 1944, his Military Occupational Specialty (M.O.S.) changed to 653 (squad leader). Assuming that his rifle squad was at full strength, Sergeant Caulk was in charge of 12 men (three fire teams, each with four men); three squads made up a platoon. Training for the invasion of the Marianas included practice landings on Guadalcanal in late May.

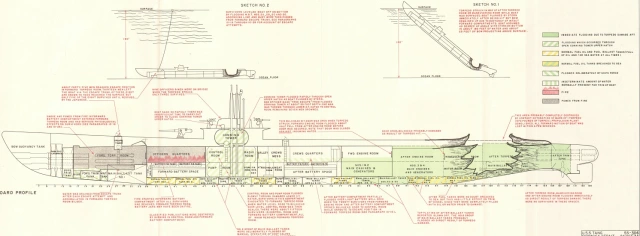

On June 2, 1944, Sergeant Caulk boarded the attack transport U.S.S. Warren (APA-53), sailing two days later. He arrived at Kwajalein, Marshall Islands on June 8, 1944. That same day, he transferred to U.S.S. LST-123. The ship sailed the following day for the Mariana Islands.

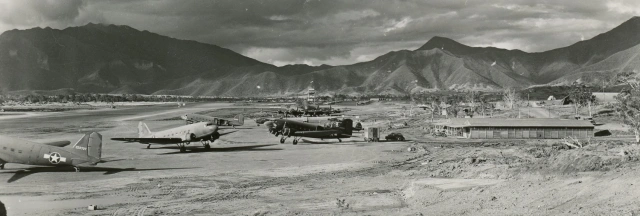

Capturing the Marianas would bring the Japanese Home Islands into range of American strategic airpower. D-Day on Saipan was scheduled for June 15, 1944, and the landings on nearby Guam for June 18 (designated W-Day). Caulk’s unit was part of the Southern Landing Force, with orders to recapture Guam. Guam was a U.S. territory that had been under Japanese occupation since December 10, 1941. W-Day was postponed due to Japanese fleet movements (culminating in the Battle of the Philippine Sea) and because American resources were shifted to Saipan. In their book Central Pacific Drive, Henry I. Shaw, Jr., Bernard C. Nalty, and Edwin T. Turnbladh wrote:

An unfortunate result of the postponing of W-Day was the extra time it afforded the Japanese to prepare. They overworked the naval construction battalions and native labor to bulwark the island, mostly in the vicinity of the beaches and the airfields.

LST-123’s war diary noted that while lingering in the vicinity of the Marianas, on June 27, 1944, “Provisions began getting low, water very low, rationed at one gallon per man per day.” As a result, the vessel headed back to the Marshall Islands, arriving at Eniwetok on June 30. In Central Pacific Drive, Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh wrote:

While the ships lingered at Eniwetok, Marines were debarked, a few at a time, for exercises on sandy islets of the lagoon, but that was hardly a respite from the average of 50 days that troops had to spend on board the hot and overcrowded ships before getting off at Guam.

The L.S.T. headed back to the Mariana Islands on July 15, 1944. About two weeks of naval and aerial bombardment preceded W-Day, now rescheduled for July 21, 1944, with H-Hour at 0830 hours. Sergeant Caulk boarded a Landing Vehicle Tracked (L.V.T., also known as amphibian tractors or amtracs) about six nautical miles offshore from Asan. The 3rd Marine Regiment would be landing on the American left, designated Red Beaches 1 and 2. Sergeant Caulk’s 3rd Battalion was earmarked to land on Red Beach 1 and take the high ground at Chonito Cliff and Adelup Point. Company “L” started out as the battalion reserve, but it was not long until the battalion commander called on them.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh wrote:

Minutes after the leading waves of the 3d Marines were ashore, the Japanese opened up in earnest, turning artillery, mortars, and machine guns upon the beaches and reef, lobbing well-directed mortar shells squarely among the LVTs. Some of the Marines were casualties before getting on land; others were hit when they were barely on the beaches by an enemy enjoying perfect observation. At 0912, the commander of 3/3 [3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment], Lieutenant Colonel Ralph L. Houser, reported “mortar fire and snipers very heavy,” resulting in “many casualties.”

Japanese fire stopped the advance of Companies “I” and “K.” The authors of Central Pacific Drive continued:

To break up the impasse, Lieutenant Colonel Houser employed flamethrowers and called upon tanks of Company C, 3d Tank Battalion, which took position along the beach road and fired squarely into the caves. The battalion commander then committed his reserve, Company L, which [in the words of Lieutenant Colonel Royal R. Bastian, Jr.] “breeched the cut and pushed on to the flat land north of Chonito Cliff. This move required the entire company to move down the beach road with the sea on the left and the steep cliff face on the right.”

By noon, the danger of Chonito Cliff had been removed, and here, at least, the 3d Marines had reached its initial objective. […] That afternoon, Marines of 3/3, supported by tanks and armored amphibians, overcame some Japanese resistance on Adelup Point […] The subsequent movement of 3/3, however, was handicapped not only by enemy fire from the front but also, particularly, by the Japanese defenses on Bundschu Ridge[.]

The following morning, July 22, 1944, the Japanese launched a fierce counterattack against 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 3rd Marines. The Japanese were so close that naval gunfire could not support the hard-pressed Marines. Reinforcements from the division reserve, along with service personnel and Marines from battalion headquarters were all engaged in the firefight. Eventually, the Japanese attack was repulsed and 3rd Battalion pursued, but heavy enemy fire stopped their advance just as it had the day before.

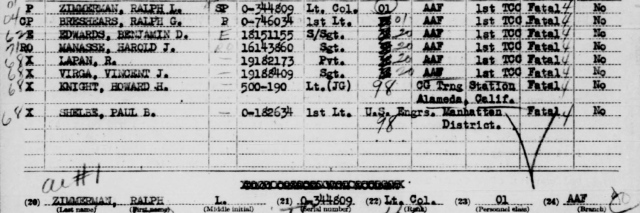

During that second day of combat on Guam, Sergeant Caulk was killed by the explosion of a grenade which severed one of his legs. He was initially buried at the Army, Navy, and Marine Cemetery No. 1 on Guam (Plot 1, Row 5, Grave 28) on July 24, 1944. After American forces overcame tough Japanese resistance, large-scale fighting on Guam ended on August 10, 1944.

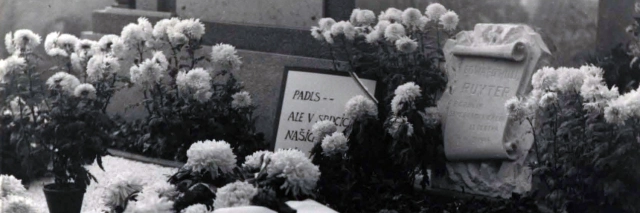

Sergeant Caulk was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. The 3rd Marine Regiment was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for the collective actions of its men on Bougainville and another for Guam. In 1947, Sergeant Caulk’s family was offered the choice of repatriating his body or leaving it in a U.S. military cemetery overseas. Caulk’s father chose the latter option. The following year, correspondence advised the Caulks that there would not be a permanent military cemetery on Guam. The options this time were to either repatriate his body or have him buried at the U.S. National Cemetery, Honolulu, Hawaii. Caulk’s mother requested that his body be returned to the United States. In early 1949, Sergeant Caulk’s body returned to the United States aboard the U.S.A.T. Dalton Victory. After services at St. Thomas’s Roman Catholic Church on April 23, 1949, Sergeant Caulk was buried in Cathedral Cemetery, located just west of the neighborhood where he grew up in Wilmington.

Documents

Click to any document to view a larger copy.

Notes

Journey to Parris Island

Even though it was Christmas Eve, Caulk and Private Drego J. Burattini (1922–1994) were ordered to report immediately to Parris Island, South Carolina for boot camp. Their travel itinerary had them catching a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad train at Chestnut Street station in Philadelphia at 3:36 p.m. that same afternoon, transferring at Union Station in Washington, D.C. to the 6:50 p.m. Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad train. If the trains were all on time, then after an overnight journey in a Pullman sleeping car, they would have arrived in Yemassee, South Carolina just before noon on Christmas Day 1941, and caught the 11:40 a.m. Charleston & Western Carolina Railway train, arriving in Port Royal, South Carolina at 12:40 p.m.

Ship to Bougainville

Caulk’s personnel file stated that he arrived at Bougainville aboard LST-207, while his unit’s muster rolls listed LST-353. Both vessels sailed in the same convoy from Guadalcanal to Bougainville.

Pay in the Marine Corps

Caulk made far less in the Marine Corps than he had as a mechanic. His base pay as a sergeant in 1944 was $78 per month, plus $15.60 sea and foreign shore duty, totaling $93.60 per month (equivalent to about $1,424 per month or $17,088 per year today’s money, based on May 2021 figures in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator).

Date of Death

Some records, including his battalion’s muster rolls, stated that Sergeant Caulk was killed in action on July 21, 1944 rather than July 22. In some records, including those in his Marine personnel file and casualty card, the earlier date was crossed off and the later date added. The reason for the discrepancy is unclear. Sergeant Caulk’s death certificate stated: “While in action on 7-22-44, Caulk was killed instantly when a grenade blew his leg off.” That document appears to the basis for the subsequent revision of documents with the earlier date.

Acknowledgments

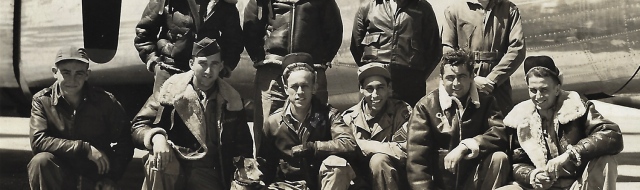

Special thanks to Sergeant Caulk’s niece, Patti Abernethy, for providing valuable documents and photographs which accompany this article.

Bibliography

Applications for Headstones, compiled 01/01/1925 – 06/30/1970, documenting the period ca. 1776 – 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774 –1985. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_2421401759_0391-02139

Caulk, Helen V. Paul Lee Caulk Individual Military Service Record, November 30, 1944. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18046/rec/2

“Mass for Sergt. Caulk To Be Said Saturday.” Journal-Every Evening, April 22, 1949. Pg. 14. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/80492564/paul-l-caulk-obituary/

Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269954-00305 (August 1943), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269904-00322 (September 1943), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269916-00324 (October 1943), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269932-00199 (November 1943), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269849-00199 (December 1943), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272384-00123 (June 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272402-00154 (July 1944).

Paul Lee Caulk Official Military Personnel File. National Personnel Records Center, courtesy of Patti Abernethy.

Paul Lee Caulk U.S. Marine Corps Casualty Card. National Archives.

Polk’s Wilmington (New Castle County, Del.) City Directory 1940. R. L. Polk & Company Publishers, 1940. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/16114412

Rottman, Gordon L. Guam 1941 & 1944: Loss and Reconquest. Osprey Publishing, 2004.

Shaw, Henri I. Jr., Bernard C. Nalty, and Edwin T. Turnbladh. Central Pacific Drive (History of U. S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, Volume III). Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U. S. Marine Corps, 1966. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/History%20of%20the%20U.S.%20Marine%20Corps%20in%20WWII%20Vol%20III%20-%20Central%20Pacific%20Drive%20%20PCN%2019000262600_9.pdf and https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/History%20of%20the%20U.S.%20Marine%20Corps%20in%20WWII%20Vol%20III%20-%20Central%20Pacific%20Drive%20%20PCN%2019000262600_10.pdf

Silverman, Lowell. “1st Lieutenant Ferris L. Wharton (1915–1944).” https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2021/05/26/1st-lieutenant-ferris-l-wharton/

Silverman, Lowell. “Seaman 2nd Class Charles L. Caulk, Jr. (1913–1942).” https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2021/06/21/seaman-2nd-class-charles-l-caulk-jr/

Stille, Mark. The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Osprey Publishing, 2018.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4295769-00970

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531894_01136

“United States Ship L.S.T. 123 War Diary for month of June 1944.” World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/279763871

U.S.S. George F. Elliott war diary. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/270621103, https://www.fold3.com/image/270621141, https://www.fold3.com/image/270621189

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_04_00002-01758

Last updated on November 8, 2021

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.