| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware | Surveyor or unemployed |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32242911 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Intelligence & Reconnaissance Platoon, Headquarters Company, 130th Infantry Regiment, 33rd Infantry Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Distinguished Service Cross, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge | Luzon |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Entered the Service From |

| 761 (reconnaissance N.C.O/squad leader) | Newark, Delaware |

Early Life & Family

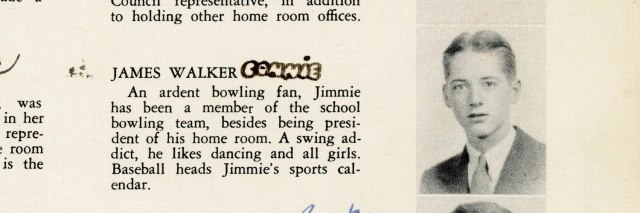

Philp Alden Beaman was born in Chester, Pennsylvania, on June 7, 1920. He was the son of Ralph Heckman Beaman (a chemist and manager in a number of different flooring factories, 1888–1975) and Sarah Elizabeth Beaman (née Probert, 1890–1978), both originally from Massachusetts. Philip’s older brother, Richard, died from influenza as an infant in the fall of 1918. Philip also had a younger brother and a younger sister. The Beaman family had moved to 219 Homestead Avenue in the Borough of Haddonfield, New Jersey, by April 15, 1930. The family moved to Somerville, New Jersey after April 1, 1935.

Beaman graduated from high school in Somerville and entered Amherst College in Massachusetts, his father’s alma mater. He ran track and cross country and worked on the Planning Committee. At the time the census was taken on April 3, 1940, the Beaman family was living at 229 East Main Street in Somerville (though Philip himself was away at college). The Beaman family had moved to 22 Kells Avenue in Newark by July 1, 1941, likely due to Ralph Beaman’s work. (The elder Beaman was was working at the Delaware Floor Products Company in Wilmington as of April 27, 1942.)

After he graduated from Amherst College in 1941, Philip rejoined his family in Newark. When he registered for the draft on July 1, 1941, he was unemployed. (Beaman’s mother wrote in an Individual Military Service Record filled out for the Delaware Public Archives Commission that her son had been drafted before getting a job, though when he joined the U.S. Army, Beaman’s occupation was recorded as “semiskilled chainmen, rodmen, and axmen, surveying.”) On his draft registration card, Beaman was described as standing five feet, 10½ inches tall and weighing 150 lbs., with brown hair and hazel eyes.

Training & Journey Overseas

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Beaman was drafted. He joined the U.S. Army at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on February 26, 1942. Soon after, he reported to Camp Forrest, Tennessee, for basic training and was assigned to Headquarters Company, 130th Infantry Regiment, 33rd Infantry Division. Beaman was promoted to private 1st class in July 1942.

The 33rd Infantry Division was not yet at full strength by September 1942 when the unit moved from Tennessee to Fort Lewis, Washington. Beaman was promoted to corporal on November 5, 1942. In March 1943, the division was transferred again—this time to Camp Clipper at the Desert Training Center near Needles, California—a move completed in April. After further training, the division moved to Camp Stoneman, California in June 1943 and then San Francisco that same month.

According to the Individual Military Service Record filled out by his mother, Corporal Beaman shipped out from California on June 13, 1943, arriving in Hawaii on July 1, 1943. However, the division history, The Golden Cross: A History of The 33d Infantry Division In World War II stated that “Colonel Coulter’s 130th Regimental Combat Team was the first Division element to leave the continental limits of the United States, passing under the Golden Gate Bridge on 22 June aboard the U.S. Army Transports Republic and Henderson.” (The 130th Regimental Combat Team consisted of the 130th Infantry Regiment and attached support units such as the 124th Field Artillery Battalion.)

Corporal Beaman’s regiment was first stationed in Hilo, Hawaii. Ostensibly, their role was to defend the island, though their training soon resumed. The regiment moved to Kauai in December 1943. Training there was especially rigorous, with a special focus on jungle and then amphibious warfare in preparation for deployment to the Southwest Pacific.

On April 21, 1944, the 130th Regimental Combat Team sailed to Honolulu, where they embarked on the luxury liner-turned transport S.S. Lurline. Corporal Beaman wrote his family that he had crossed the Equator on April 26, 1944. The document filled out by his mother suggests that Beaman was assigned to the Intelligence & Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon during the entire time he was in the Southwest Pacific (though it is likely that he joined that platoon stateside). In a February 18, 1946, letter to Delaware’s archivist, Beaman’s mother wrote: “Philip had written over 600 letters but was very careful not to tell us any names of places or ships – he knew the reason for keeping these things secret because of his training in Intelligence Unit.”

New Guinea & Morotai

After two weeks at sea, Corporal Beaman’s ship arrived in Finschhafen, in eastern New Guinea. During the following months, the men of the 33rd Infantry Division worked to build up the outpost and conducted additional amphibious operation training. They were even put to work unloading supplies at the port due to a shortage of stevedores. Only a small portion of the division saw combat in New Guinea. According to The Golden Cross, “Most men in the Golden Cross began to feel that the Division was World War II’s forgotten unit. They began to call themselves the ‘4F’ Division—the Finschhafen Freight Forward Force.” Beaman was promoted to sergeant on July 1, 1944, and became a squad leader in the I&R Platoon.

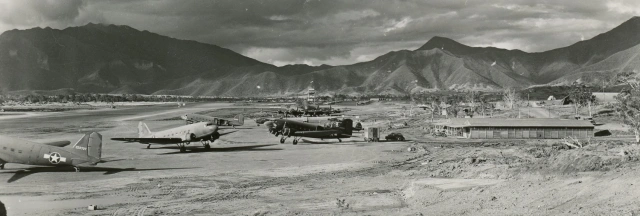

In December 1944, the 130th Infantry Regiment—along with most of the 33rd Infantry Division—shipped out to the Gila Peninsula on Morotai Island in the Maluku Islands (part of present-day Indonesia). American forces had seized the three months earlier and built an air base to support the recapture of the Philippines. According to The Golden Cross, “On 21 December Division troops streamed ashore on the humid peninsula. Everyone noticed a difference in temperature immediately. If Findschhafen was hot, Morotai manufactured the rods that stoked the fires of hell.”

The Japanese launched multiple air raids against American installations on the island. Despite interdiction by U.S. Navy patrol torpedo boats, the Japanese managed to land a regiment on the island. The Japanese force was small and lacked heavy weapons but proved difficult to dislodge from the thick jungle in the area referred to as Hill 40. American forces took Hill 40 in early January. It is not clear whether Sergeant Beaman saw any combat on Morotai, since the assault on Hill 40 was primarily carried out by the 136th Infantry Regiment, supported by one battalion of Beaman’s regiment, the 130th.

The Philippines

With Morotai secured, the 33rd Infantry Division shipped out to the Philippines on January 26, 1945. They began landing in Lingayen Gulf on February 10, 1945, about one month after the first American troops landed on Luzon.

Most men of the 130th Infantry Regiment first saw combat in the foothills of the Caraballo range nicknamed Bench Mark and Question Mark. As a member of the regimental Intelligence & Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon, Sergeant Beaman would have probably been involved in probing Japanese positions around February 16, 1945, prior to an all-out attack on February 19. (The Golden Cross stated that “Patrol actions highlighted the waiting period.”) The Japanese positions fell to the 130th and 136th Infantry Regiments after four days of heavy fighting. The 130th followed up with smaller actions to clear small groups heavily entrenched Japanese soldiers from nearby hills.

According to The Golden Cross, “On 3 March [1945,] Division selected two new routes for the main effort towards Baguio.” The 130th’s “path of advance carried up the coastal road from Agoo through Aringay and Bauang to San Fernando[.]” Both the coastal route planned for Sergeant Beaman’s 130th Regiment and the inland route assigned to the 136th Regiment “were virtually unexplored by American forces and Division lacked complete data on how strongly the enemy had garrisoned them.”

Firefight Near Aringay

The division history continued: “Regimental plans called for a small group of infantrymen, heavily reinforced, to move towards Aringay as a reconnaissance in force.” Early on the morning of March 7, 1945, this force (including Sergeant Beaman’s I&R Platoon) seized Aringay under cover of darkness without opposition. With the town secured, The Golden Cross continued,

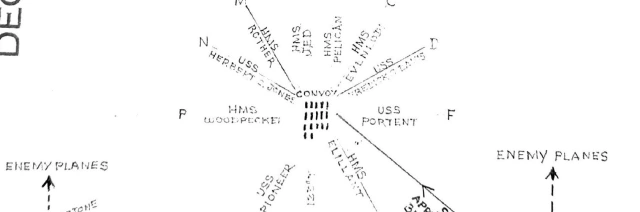

Patrols went out to reconnoiter sections of the road and a string of hills north of Aringay and east of the highway. Foremost of these hills was 1,000-foot Mount Magabang which commanded an excellent view of Aringay. The I&R Platoon, under Lieutenant Lyon, was told to reconnoiter Magabang and determine whether it was manned by the enemy.

A radioman in I&R Platoon, Technician 5th Grade Keith E. Carr (1922–2014), recalled in a pair of oral history recordings (recorded in 2011 and 2012) that at the platoon briefing the morning of March 7, he was told that G-2 (intelligence staff) believed that there were no Japanese in the area. Carr stated that the entire 21 or 25-man I&R Platoon moved out around 0930 hours, accompanied by a medic who volunteered for the mission as well as two Filipino guides.

The division history stated:

Lyon, moving slowly in order to search the many draws leading down from Magabang, found no Japanese during his approach march. As he prepared to mount the slope of the objective, Lyon radioed his position and lack of contact to battalion headquarters. The platoon then began the ascent, moving along a densely wooded spur that ran straight to the crest of Magabang. When the last man in the column had been swallowed up in the thick vegetation, two platoons of enemy, located on each side of the spur, opened up on Lyon’s force, catching the entire platoon in a murderous crossfire.

Technician 5th Grade Carr recalled things somewhat differently. He stated that the platoon had stopped for a meal of K-rations around 1130 to 1200 hours. Two men who had announced that they were going to try to find water returned yelling that the enemy was nearby.

“Boy, you ought to see us scatter and get into position,” Carr recalled. “And just about that same time […] they started opening up on us and they started firing machine guns, I guess everything they had.” From Carr’s vantage point, it seemed that there must have been over 200 Japanese soldiers.

Carr stated that Technician 5th Grade Albert P. Hays “tried to crawl up there and knock that machine gun out. He was hit by machine gun fire and killed.” Hays (1916–1945) was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his action.

Carr recalled that he was next to a buddy, returning fire, when a Japanese grenade exploded nearby, severely wounding his right arm. Carr’s buddy told Carr to follow him. Carr recalled: “As we get up, he went to the left. I went to the right. […] I took about two steps. And I was right face to face to the Jap[anese soldier] that threw the grenade.”

The enemy soldier was armed with another grenade. Although Carr was still carrying his rifle in his left hand, he was unable to use it because of his mangled right arm.

“I knew I had to do something,” Carr recalled. “And what I did was probably dumb, but it’s the only thing I could think of at the time.” Carr dropped his rifle and threw his good arm around the Japanese soldier. Carr’s immediate priority was to prevent the enemy from igniting the grenade’s fuze, which on Japanese grenades was done by striking a hard object. Despite his injuries, Carr’s action bought him a few seconds.

“All he was trying to do was bend over to the ground to hit [the knob on the grenade] to set it off. And I knew if he did, he’d hold it between us” until it detonated, Carr recalled. “And I look to my right and there is Sergeant Beaman, putting his bayonet on. I knew then he was afraid to shoot for fear we’d move and he’d shoot me.”

From his vantage point, the Japanese soldier couldn’t see Sergeant Beaman, and Technician 5th Grade Carr did his best to keep it that way. Carr stated that Beaman “[came] charging across. I think he was hit before he bayonetted the Jap[anese soldier…] And then all three [of us] went down together” into a field of cogon grass. Carr checked on Beaman, but found he was already dead from multiple machine gun wounds. Two rounds from the same burst that killed Beaman also grazed Carr.

Carr recalled that the cogon grass was barely more than knee high, but it was enough to conceal him from the Japanese. Although “down in this grass, you had no idea which way you’re going,” Carr began crawling as machine gun fire ripped through the field around him. Fortunately for Carr, after crawling about 40 or 50 feet, he heard the voices and found about half the I&R Platoon, including Lieutenant Lyon, sheltering in a ravine on the side of the mountain. Luckily for Carr, the medic was in the group and began treating Carr’s wounds. (Carr recalled that medics did not usually accompany their patrols, but on this particular day, the medic had apparently volunteered to join the I&R Platoon mission out of boredom.) It was only when his comrades started to run low on ammunition that Carr reluctantly surrendered his rifle to someone who could still use it.

The Golden Cross gave this account of the engagement:

Even though [enemy] fire was pouring into their ranks from point-blank range, members of the platoon could see no enemy or guns. Only after they deployed and brought answering fire to bear on suspected gun positions could they correctly diagnose the situation. Barring the platoon’s path to Magabang was the most cleverly camouflaged group of [Japanese] yet encountered by the 130th on Luzon. Light machine guns had been dug deep into the cogon grass on the hillside and Japanese gunners were firing along wafer-thin fields of fire cut through the grass. Each emplacement had a cloak of cogon shrouding it to blend with the background. In the same manner, enemy riflemen protecting the machine guns were clothed in caps and capes of matching cogon grass. After a short fire fight Lyon’s men were forced to gather their casualties and withdraw back to Aringay.

The division history recorded that the following morning, after an intense artillery and mortar bombardment, Company “C” easily captured Mount Magabang, and “With this high ground in 130th Infantry hands Aringay was secure.”

Aftermath of a Battle

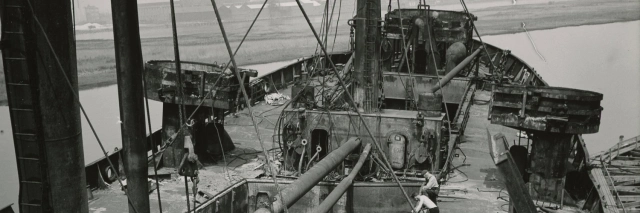

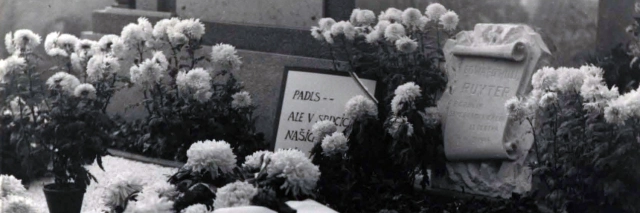

Sergeant Beaman was initially buried at a military cemetery at Santa Barbara, Pangasinan Province, Luzon. Around 1948, his body was moved to the cemetery at Fort McKinley, now known as the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial. Sergeant Beaman was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his act of courage in saving Technician 5th Grade Carr’s life, as well as the Purple Heart.

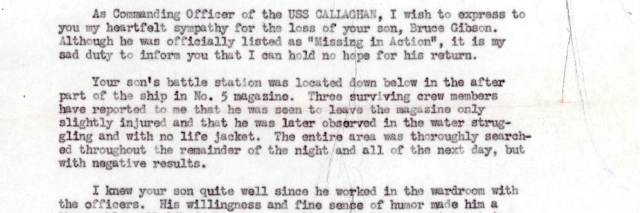

After Sergeant Beaman’s death, his company commander, Captain Charles A. Campbell, wrote a letter to Beaman’s father which stated in part:

Philip had always been one of the finest soldiers in his company. He was well known and admired by every officer and enlisted man,…and we felt deeply the loss of such a true friend and comrade…we will never forget the example of courage and devotion to duty he set for our emulation.

Another letter, from Chaplain Stewart W. Hartfelter stated that Sergeant Beaman was “one of the most able, most diligent and most conscientious soldiers in the entire regiment,…serious at all times in the performance of his duties and deeply aware of the great fundamental principles that are at stake in this war.”

Such words were surely of only limited comfort. In her February 18, 1946, letter to the Delaware archives, Sarah E. Beaman lamented: “Nothing can ever help us in the loss of our son. He, and many other educated, decent, men who gave their lives could do so much more for their country living, today. Would that he were with us!”

Journal-Every Evening reported on December 4, 1948, that Sergeant Beaman “will be honored by the U. S. Army, which plans to name a harbor craft in his memory.”

Technician 5th Grade Carr was treated at the division clearing station and transferred the following day to the 57th Portable Surgical Hospital. He very nearly succumbed to his wounds. Once his condition improved, in late May 1945, Carr was evacuated to San Francisco by air aboard a C-54 (a torturous journey with intermediate stops on Guam, Kwajalein, Johnston, and Honolulu). Recuperating at Thayer General Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, Carr met Ruby Hargis, his future wife. He was awarded a Silver Star for his actions in fighting the Japanese soldier with the grenade. Carr was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army there on December 5, 1945. The couple had three children.

Carr never forgot Beaman’s act of sacrifice. “Sergeant Philip Beaman knew that I would have done the same thing for him,” he recalled. Around 1982, one of Carr’s daughters found out where Sergeant Beaman was buried. Carr arranged to have flowers placed on Beaman’s grave in the Philippines every Memorial Day for decades, until his death on November 10, 2014, aged 92.

Distinguished Service Cross Citation

The Hall of Valor Project has the original text for Sergeant Beaman’s Distinguished Service Cross citation (General Orders No. 131, Headquarters, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, dated June 5, 1945):

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Sergeant Philip A. Beaman (ASN: 32242911), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving with the 130th Infantry Regiment, 33d Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces near Mount Magabang, Luzon, Philippine Islands, on 7 March 1945. On that date Sergeant Beaman was a member of a patrol which was suddenly ambushed and surrounded by a superior force. As the troops endeavored to fight their way out, he observed a wounded comrade struggling with a Japanese who was trying to release a grenade. With machine gun fire directed at him from two sides he sprang up, killed two enemy soldiers who tried to stop him, and rushed to the aid of the wounded man. Although hit in the back and stomach by machine gun fire, he pressed forward, reached the wounded man and killed his adversary with his bayonet. When aid arrived he ordered the wounded man removed first. Taking up his rifle and providing covering fire, he was killed by enemy fire while his comrade was being removed. Sergeant Beaman’s voluntary and heroic sacrifice of his life to protect a fellow soldier was in keeping with the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 33d Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

Notes

Analysis of the Firefight

I assembled Carr’s account of the battle from a pair of oral history recordings made in 2011 and 2012. Although the accounts are virtually identical, one interview was sometimes clearer than the other regarding certain details.

The Distinguished Service Cross citation’s summary of the firefight near Mount Magabang is generally consistent with the division history and Technician 5th Grade Carr’s accounts. The citation stated that Carr was wounded before reaching the Carr, something that Carr agreed was possible.

The citation also states that Sergeant Beaman killed three Japanese soldiers in the process of saving Carr. Carr’s accounts only mentioned that Beaman killed the Japanese soldier armed with the hand grenade, though conceivably he could have been too preoccupied to notice.

The biggest discrepancy is that in Carr’s account, Beaman was killed within moments of killing the Japanese soldier and did not remain behind to cover Carr’s escape. Carr also stated that he was able to crawl back to the rest of the platoon without assistance.

Both the citation and 33rd Infantry Division history emphasize the firefight as being a Japanese ambush. Carr’s account, on the other hand, indicates that the I&R Platoon was caught off guard by a Japanese attack while stopping for lunch. The lack of resistance in the town of Aringay earlier that morning combined with the briefing suggesting that no Japanese were in the area were undoubtedly factors. In addition, though the men of the 130th Infantry Regiment had been training together for as long as three years, the unit had been in combat for less than a month.

I believe Carr’s account is probably accurate. The Distinguished Service Cross citation and division history would naturally be expected to portray the unit in a favorable light, but Carr would have little reason to portray his platoon as being caught flatfooted if it wasn’t true.

All accounts agree about the most salient fact: Sergeant Beaman sacrificed his life in the process of saving the life of a wounded friend.

Acknowledgments

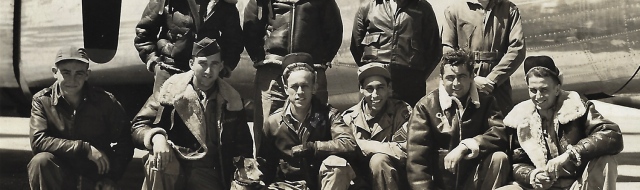

Special thanks to Michael Belluomo for providing documents, references, photographs, and a recording that were all vital in telling Sergeant Beaman’s story, and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“1941.” Amherst Graduates’ Quarterly, circa 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17631

The 1941 Olio. Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1265/images/40392_b066009-00039

Beaman, Sarah E. Philip Alden Beaman Individual Military Service Record, circa 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17627/rec/1

Beaman, Sarah E. Letter to Leon deValinger, Jr., State Archivist of Delaware, dated February 18, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17633

Carr, Keith E. Family oral history recording, 2011. Courtesy of Michael Belluomo.

Carr, Keith E. Interview conducted by Kevin Lause at the Birchard Public Library in Fremont, Ohio, on November 1, 2012. Keith Edward Carr Collection

(AFC/2001/001/87985), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/bib/loc.natlib.afc2001001.87985

“Corp Albert Paul Hays.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/28884735/albert-paul-hays

“Craft to Be Named For Newark War Hero.” Journal-Every Evening, December 4, 1948. Pg. 20. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/58919954/philip-a-beaman/

The Golden Cross: A History of The 33d Infantry Division In World War II. Infantry Journal Press, 1948. https://archive.org/details/TheGoldenCross

“Keith E. Carr.” News-Messenger, November 13, 2014. https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/thenews-messenger/obituary.aspx?n=keith-e-carr&pid=173140040&fhid=8057

Morning reports for Headquarters Company, 130th Infantry Regiment. March 1945. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri.

“Philip A. Beaman.” Journal-Every Evening, April 10, 1945. Pg. 4. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/54142118/philip-a-beaman/

Philip A. Beaman Distinguished Service Cross Citation in General Orders No. 131, Headquarters, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, June 5, 1945. The Hall of Valor Project. https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/21879

“Ralph Heckman Beaman.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/74150198/ralph-heckman-beaman

“Richard Probert Beaman.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/87340170/richard-probert-beaman

“Sgt. Beaman Killed in Battle for Luzon, Mar. 7.” The Newark Post, May 10, 1945. Pg. 6. https://udspace.udel.edu/bitstream/handle/19716/18981/np_036_13.pdf

“Sgt Philip Alden Beaman.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56774706/philip-alden-beaman

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4660861_00239

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02383-00623

U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/702014879-beaman-philip-a

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/86107589-philip-a-beaman

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, 10/16/1940–3/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_13_00001-00739, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1002/images/DE-2240331-1373

Last updated on March 17, 2023

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.