| Home State | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware | Worker in family farm products store |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army Air Forces | 6855191 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | 17th Pursuit Squadron, 24th Pursuit Group |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart, P.O.W. Medal (presumed) | Bataan (1942) |

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my previous article about Private 1st Class John E. Adams, Jr., whose unit fought alongside Eisenman’s during the Battle of the Points and who also perished in the sinking of the hell ship Shinyo Maru.

Early Life & Family

Martin Eisenman was born at 1123 Railroad Avenue in Wilmington, Delaware, on December 28, 1916. He was the son of Israel Eisenman (a merchant, 1874–1946) and Minnie Eisenman (née Diamond, 1892–1972), Jewish immigrants from Russia. He had two older half siblings, as well as an older sister, a younger sister, and three younger brothers. By September 12, 1918, the Eisenman family had moved to 228 King Street. They were still living there when tragedy struck a few years later. Eisenman’s younger brother, Abraham, died on January 30, 1922, after he was burned in an accident, aged three.

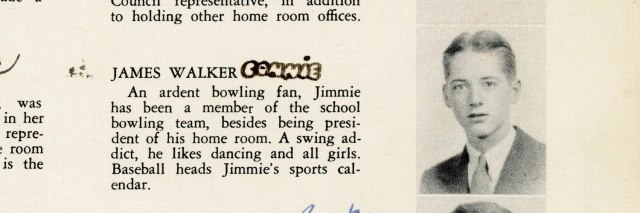

The Eisenman family was recorded on the census on April 5, 1930, living at 101 East 7th Street in Wilmington. There is conflicting information about Eisenman’s education. His 1940 enlistment data card stated that Eisenman had completed two years of high school. Indeed, a September 8, 1943, Journal-Every Evening article stated that Eisenman “attended Bancroft and Wilmington High Schools.” Curiously, the 1940 census stated that he had only completed the 8th grade.

Service in Panama & Return to Civilian Life

According to a service summary compiled by Colonel Charles D. Carle in 1946 in response to a request by Eisenman’s sister, Etta (later Etta Eisenman Barnett, 1922–2017), Eisenman enlisted in the Regular Army on March 5, 1935, in Washington, D.C. He volunteered for service in Panama. That same day, he transferred to the Overseas Recruiting Depot at Fort Slocum, New York. Carle wrote that Eisenman “left the United States for duty in the Panama Canal Department 4 April 1935 and arrived in Cristobal, Canal Zone 12 April 1935.”

On April 19, 1935, Private Eisenman joined Company “I,” 14th Infantry Regiment at Fort Davis. He was promoted to private 1st class in April 1936. On November 21, 1936, Private 1st Class Eisenman transferred from Company “I” to Company “F,” 14th Infantry. Although that company was also located at Fort Davis, he was not transferred in grade and joined Company “F” as a private. On April 15, 1937, Private Eisenman sailed aboard the U.S.A.T. St. Mihiel, bound for Brooklyn, New York. He was honorably discharged on April 27, 1937.

After his stint in the Army, Eisenman returned to Wilmington. At the time he was recorded on the census on April 4, 1940, Eisenman was living with his family at 200 West 37th Street in Wilmington. Eisenman worked in his parents’ store, where the family sold milk, butter, and eggs.

Martin’s younger brother, Norman Eisenman, recalls that Martin enjoyed military life. Despite his devotion to his family, Eisenman’s niece explained, Martin did not want to work in the family business for his entire life. He decided to reenlist in the Regular Army in Wilmington, Delaware, on August 8, 1940. This time, he joined the Army Air Corps, volunteering to serve in the Philippine Department.

Norman recalls sitting outside on the steps of his house and watching his brother leave. “I was the last one of my family actually to see him alive,” he recalls, “because I watched him walk down the street and get on the bus.”

Second Enlistment

After rejoining the U.S. Army, Private Eisenman spent 45 days traveling to the Philippine Islands by sea. In a letter to a friend of the family, dated July 10, 1941, Eisenman wrote that he sailed

from New York City, stopping one day at Charleston, S.C., Panama twenty four hours, San Francisco one week, Honululu [sic] one day and Guam Also. I also saw Wake Island from the ship. The weather was fine all the way over. In Honululu I visited Wakikie [sic] Beach,to me it was just another beach, and far from the best. I have been in the Philippine Islands eight month and havent [sic] seen as much as I’d like to. However, I have visited many interesting places of interest in and within the vicinity of Manila. As you already know I am with the 17th Pursuit Squadron and my work being an airplane mechanic, which I enjoy being very much. I arrived in Iba several days ago and it is very enchanting to see.

According to Colonel Carle’s statement, Eisenman joined the 20th Air Base Group (Reinforced) at Nichols Field on Luzon on November 1, 1940. He wrote that on February 14, 1941, Eisenman transferred to the 17th Pursuit Squadron of the 4th Composite Group. The 17th Pursuit Squadron had arrived in the Philippines on November 23, 1940. Initially equipped with obsolescent P-26s and later P-35As, by the beginning of the Pacific War, they were stationed at Nichols Field and equipped with newer aircraft, 18 P-40Es. The squadron transferred to the control of the new 24th Pursuit Group on October 1, 1941.

According to a 24th Pursuit Group history, three weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor, with war imminent, “all pursuit aircraft [in the Philippines] were fully loaded, armed and on constant alert 24 hours each day with pilots available on 30 minutes notice.”

Eisenman was promoted to sergeant on an unknown date. On November 17, 1941, he mailed his watch home to his family. It was the last they heard from him for nearly two years.

Defense of the Philippines

In the nights leading up to the start of the war, mysterious aircraft—presumably Japanese aircraft flying from Formosa (Taiwan)—were detected in the vicinity of Clark Field. American aircraft, including the 17th Pursuit Squadron, attempted to intercept these intruders without success. The inadequacies of the Philippine air warning network would become even clearer after the fighting began. To make matters worse, as Major (2nd Lieutenant during the Philippine Island campaign) David L. Obert (1919–1991) later wrote in a report, “A fighter control organization exited on Luzon but the pursuit pilots in general were not familiar with fighter control procedures and very little training had been done as concerned controlled interceptions.”

It was December 8, 1941—the Philippines was on the other side of the International Date Line from Hawaii—when Japanese aircraft began attacking the Philippines, soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The 17th Pursuit Squadron scrambled to intercept an air raid reported as being impound to Manila. Instead, the Japanese raid devastated Clark Field, destroying much of Far East Air Force’s bomber force on the ground as well as several fighters. In the days that followed, most American aircraft were destroyed by the Japanese or mishaps at airfields, doing little damage to Japanese aircraft in return.

The 17th Pursuit Squadron transferred to Clark Field on December 9, 1941. Major (2nd Lieutenant during the campaign) Nathaniel H. Blanton (1915–2006), formerly a pilot in the 17th, later wrote that as of that date:

A portion (what percent I do not know) of the enlisted men of the 17th Pursuit Squadron had been transferred to Clark Field to join forces with the 3rd and 20th Squadron personnel in maintaining the aircraft of the 17th and the few remaining aircraft of the 3rd and 20th who had unfortunately lost most of their aircraft landing, taking off, or on the ground at their respective fields.

Remaining aircraft flew from Clark Field against the incoming invasion fleet to little effect. The 24th Pursuit Group history stated that by the night of December 10, 1941, the group had been reduced from 72 operational fighters to about 30. The remaining fighters were conserved for reconnaissance, intercepting Japanese reconnaissance aircraft, and the occasional strike.

After the Japanese landings at Lingayen Gulf, the Americans had no choice to evacuate Clark Field. By the end of December, forces on Luzon began withdrawing to the soon to be infamous Bataan Peninsula. Obert recalled evacuating Nichols Field on December 24, 1941.

Although the prewar War Plan Orange-3 called for a withdrawal to Bataan if the Japanese invaded the Philippines, few supplies had been stockpiled there. General Douglas MacArthur had also delayed executing the plan until two weeks into the invasion in the vain hope that American and Filipino forces could halt the Japanese without ceding most of the archipelago. The delay meant that forces evacuating to Bataan had no choice but to abandon food and equipment that would be desperately needed in the months ahead—indeed, during the first week in January 1942, the defenders’ rations were drastically reduced to conserve what food remained. Still, with Bataan and the island fortresses in Manila Bay in American-Filipino hands, the Japanese were denied use of the vital port. Allied defeats elsewhere in the Pacific Theater left the Japanese in control of land, sea, and air for hundreds of miles around Bataan. There would be no relief force bringing reinforcements. Only a handful of defenders escaped aboard torpedo boats, aircraft, and submarine.

By January 3, 1942, the 24th Pursuit Group was down to 18 P-40s—most of them in great need of a full overhaul—split between Bataan and Pilar Fields. As the situation grew more and more desperate, the U.S. Army Air Forces personnel, lacking aircraft to fly or maintain, were pressed into service as infantrymen on the southwestern Bataan coast. Indeed, the group history stated that “Field Order #4, Hq, Philippines Department, [January 1, 1942], appointed the 24th Pursuit Group as the 2nd Infantry Regiment (Prov[isional]) of the 71st Division[.]”

It’s not certain that Sergeant Eisenman was assigned as an infantryman, but he would have been a logical choice. Unlike many of his squadronmates, Eisenman had served as an infantryman for years in Panama. The group history states that “The 17th Pursuit Squadron was moved from Nichols Field and Manila to Pilar and thence to Kabobo Point where they took up beach defenses.”

The 17th Pursuit Squadron was among the rear echelon units guarding southwestern Bataan. Beginning on the night of January 22, 1942, the Japanese attempted an amphibious operation to land two battalions on the southwest side of the Bataan Peninsula. The Japanese force was scattered and relatively weak, but as Clayton Chun wrote, “The only American and Filipino troops defending this area where a mixed force of FEAF airmen, Marines, sailors, and Philippine Constabulary and many of these defenders only had rudimentary training as infantry.” What followed came to be known as the Battle of the Points.

Early on January 25, 1942, a group of men from Company “A,” 803rd Engineer Battalion (Aviation), the 17th Pursuit Squadron, and the Philippine Constabulary went into action against Japanese troops at Quinauan Point. Due to their inexperience and the thick terrain, progress was slow. Though they did not prove to be particularly effective infantrymen, the American and Filipino troops were able to contain the Japanese landing force until reinforcements arrived. Chun wrote that Major General Jonathan M. “Wainwright’s troops at Quinauan Point used combined tank and infantry operations to press the Japanese who were located in a series of isolated pockets.”

On February 13, 1942, the Americans and Filipinos completed the annihilation of both Japanese battalions, ending the Battle of the Points. With their amphibious operation against southwest Bataan foiled and their main body unable to pierce American and Filipino defenses further north, the Japanese temporarily halted their offensive to await reinforcements.

Though the defenders exalted at their victory, events elsewhere in the Pacific had already sealed the fate of the Philippines. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was just the first of a series of disasters for the Allies that went on, practically unmitigated, for five months. Guam, Wake Island, and the Gilbert Islands fell in December 1941. Malaya fell in January 1942. Singapore capitulated in February 1942 and Dutch East Indies the following month. The American, British, Dutch, and Australian navies suffered devastating loses in a series of engagements, most notably the Battle of the Java Sea in February 1942. The Allies were not prepared to risk what assets they had left on a relief mission to the Philippines. With the Japanese in control of land, air, and sea for hundreds of miles around the Philippines, it was also impossible to stage a Dunkirk-like evacuation of the men on Bataan.

Prisoner of the Japanese

In the spring of 1942, after the Japanese brought in heavy artillery and reinforcements, American and Filipino resistance collapsed on the Bataan Peninsula. The few remaining P-35 and P-40 fighters (records are a little confusing but seem to be between three and six) on Bataan withdrew to Mindanao. The remaining 24th Pursuit Group personnel left behind, including Sergeant Eisenman, became prisoners of the Japanese by April 9, 1942. The infamous Bataan Death March followed. Japanese soldiers ordered the American and Filipino prisoners north, mostly on foot, subjecting them to constant brutality and often, murder. Thousands of Filipino prisoners and hundreds of Americans died before they arrived at Camp O’Donnell.

Soon after, Eisenman most likely moved to the Cabanatuan prison camp on Luzon. Indeed, a 17th Pursuit Squadron roster—that 1st Lieutenant A.W. Balfanz, Jr. (1917–1946) managed to compile as a prisoner—reported that as of October 5, 1942, Eisenman was at Cabanatuan and in “Fair Health[.]” Malnutrition and disease were rampant there and attempts at escape were punishable by death.

In December 1942, the War Department reported to Sergeant Eisenman’s family that he was a prisoner of war, but it was another nine months before they received any mail from him directly.

On an unknown date, Eisenman moved to the Davao Penal Colony on Mindanao. Originally built under American administration in the 1930s, the Japanese began using it for American prisoners after their conquest of the Philippines. The first prisoners from Cabanatuan and Cebu arrived there in November 1942. Conditions were generally better than they had been at Cabanatuan, but food supplies were still inadequate and the guards frequently brutal.

As of March 1943, prisoners performing labor received daily rations of 525 grams of rice and 300 grams of vegetables, while those who did not work received only 400 grams or rice and 200 grams of vegetables. Men received 15 grams of sugar per day and sometimes oil, oleomargarine, and salt. Red Cross shipments were occasionally permitted with additional supplies. The only regular source of protein was fish, around once per week. The diet provided less than half the calories—to say nothing of vitamins and minerals—that the prisoners needed. Despite abundant fruit growing in the vicinity of the prison, the Japanese guards forbade the prisoners from eating it. Although some prisoners managed to smuggle fruit into the camp, most of it rotted on the ground. Beriberi was common due to thiamine deficiency. Medical supplies were limited, but fortunately the camp hospital had quinine to treat the malaria that afflicted many of the prisoners, who were forced to work even when sick. Dysentery and dengue fever were also common.

Guards beat prisoners working in the rice fields if they thought they were not working hard enough. Private 1st Class Roy Allen, Jr., a survivor of Davao Penal Colony, recalled being hung by his thumbs as punishment for striking a Japanese guard. Another time, a guard struck Allen’s feet with his rifle butt for refusing to destroy an American flag. Allen stated that prisoners were sometimes punished in a hothouse, whipped, beaten with sticks, or subjected to fake executions with unloaded weapons.

Eisenman’s brother recalls a story told by a survivor of the Davao Penal Colony—likely Lyle G. Knudson—who knew Sergeant Eisenman. “The Japanese would throw their packs of cigarettes away,” Norman Eisenman recalls. “So, my brother collected them. And he ripped them in such a way they were square til he had 52 clear, so he could make a deck of cards.”

Eisenman’s family received two postcards from him on September 7, 1943. According to an April 26, 1945, Journal-Every Evening article, the family received a total of about six postcards by the end of 1944.

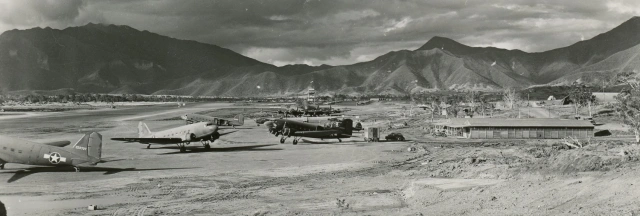

As the war dragged on, the Japanese further slashed their prisoners’ already meager rations. In early 1944, Sergeant Eisenman was assigned to construction work at a Japanese airfield on Mindanao, most likely Lasang.

Hell Ship: Shinyo Maru

With the American return to the Philippines imminent, the Japanese decided to move most of their prisoners to camps in Japan. Many were transported in crowded, inhumane conditions without adequate food, water, or sanitation facilities aboard what came to be known as hell ships. In his book Death on the Hellships: Prisoners at Sea in the Pacific War, Gregory F. Michno wrote that about 21,000 Allied prisoners of war died aboard Japanese hell ships during World War II, of whom approximately 19,000 were killed when their vessels were sunk by Allied submarines or aircraft.

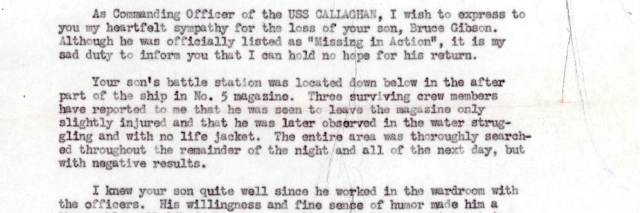

On August 20, 1944, Sergeant Eisenman sailed from Tabunco, Mindanao, with a group of 750 prisoners (including at least three other members of his squadron), arriving at Zamboanga four days later. On September 3, 1944, the prisoners transferred to another ship, the Shinyo Maru. Michno wrote that “About 500 men went into the after hold and 250 in the forward hold. Disconcertingly, the prisoners watched as the Japanese practiced drills to kill them if they were attacked by submarines.”

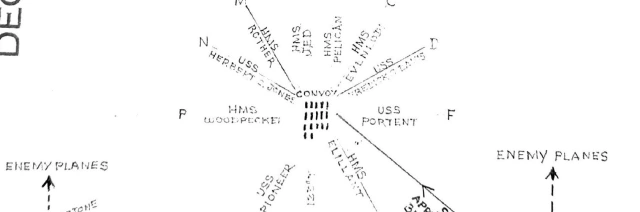

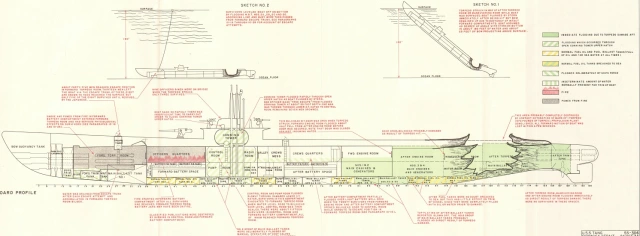

On September 4, 1944, Shinyo Maru set sail in a small convoy bound for Manila. Three days later, on the afternoon of September 7, 1944, as the Japanese ships hugged the coast near Sindangan Point, on the western coast of Mindanao, sailing at approximately 9.5 knots, they were intercepted by the submarine U.S.S. Paddle (SS-263) under the command of Lieutenant Commander Byron H. Nowell (1913–1992). Although alerted to the convoy by intercepted Japanese communications, Nowell was unaware that prisoners were aboard.

In his war patrol report, Nowell wrote that his primary target was the lead merchant ship in the convoy, which, as a tanker, he considered “the most valuable ship of the convoy.” Nowell slipped past the convoy’s escorts. Beginning at 1651 hours, he launched four torpedoes at the tanker, followed by two more at the next ship in line, which he identified—rather ironically—as a medium freighter, “not heavily loaded.”

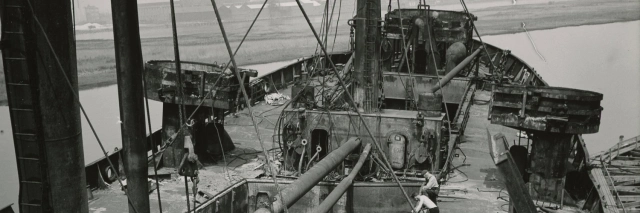

Two torpedoes struck the tanker Eiyo Maru No. 2, causing heavy damage. About a minute later, at 1653 hours, both torpedoes aimed at the Shinyo Maru struck. Michno wrote that “One torpedo hit forward of the bridge and a second between the aft hold and rear superstructure. Almost immediately, another explosion, perhaps from the boilers, shattered the hull.”

Some prisoners were killed outright or trapped in the wreckage. Survivors later reported that after the torpedoes hit, the Japanese guards immediately began attempting to murder the prisoners, opening fire on them and throwing grenades into the hold. (One prisoner interviewed decades later stated that the guards started murdering prisoners after the Japanese crew spotted the torpedoes inbound, but before they hit.) Shinyo Maru sank in about 15 minutes. The U.S.S. Paddle fled the area, evading depth charges dropped by the convoy’s escorts.

Hundreds of prisoners went down with the Shinyo Maru or were murdered on board, but well over 100 managed to abandon ship. Even then, the Japanese fired on the survivors from boats, other ships in the convoy, even aircraft. The damaged Eiyo Maru No. 2 beached on the shore nearby. A group of about 30 prisoners were picked up from the water and brought to the tanker. Later that evening, the Japanese bound and began executing them one by one, killing all but one man who managed to escape overboard.

667 prisoners were killed in the sinking or murdered by the Japanese. They died just six weeks before Allied forces began reconquering the Philippines. In all, just 83 of the 750 prisoners managed to reach shore, one of whom died of pneumonia soon afterward. The survivors were rescued by Filipino guerillas, who cared for them until they were picked up by another American submarine (except for one man who, remarkably, volunteered to remain behind and continue to fight the Japanese). Sergeant Eisenman was not among the survivors.

Journal-Every Evening reported on April 26, 1945, that in November 1944, the War Department told the Eisenman family that Sergeant Eisenman was aboard a ship that had been sunk. Authorities confirmed his death in February 1945.

Captured Japanese records indicated that there were 157 guards (a majority of whom were civilian) aboard the Shinyo Maru. 12 military and 41 civilian guards were reported killed in the sinking. A Japanese officer and three civilian guards were killed in an ambush by guerillas while returning to Manila on September 14, 1944. I have found no information about the fate of the remaining 96 guards, nor any indication that any who survived the war were punished for war crimes. Michno wrote that “Gen. Kou Shiyoku, one-time chief of POW camps in the Philippines, was put to death for command responsibility of the killing of the men escaping from Shinyo Maru.”

A survivor of the Shinyo Maru, Sergeant Lyle G. Knudson (1920–1999) of the 27th Bombardment Group (Light), was later stationed at New Castle Army Air Base in Delaware after his rescue. Knudson made the point of visiting the Eisenman family “and told them he remembered their son very well at the camp in the Davao penal colony” as Journal-Every Evening reported on April 26, 1945.

Norman Eisenman recalls that after Sergeant Eisenman’s Purple Heart arrived, his mother displayed it in the family’s grandfather clock. Year after year, he said, his mother “cried every night, every night.”

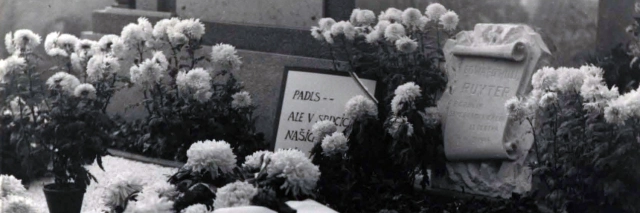

Sergeant Eisenman is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial, at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware, and on a memorial at the Jewish Community Cemetery for local Jewish servicemembers killed during World War II.

As of October 22, 2021, Eisenman is one of 105 Delawareans whose bodies remain unaccounted for following World War II, according to a list compiled by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

Notes

Israel Eisenman

After this article’s initial publication, Sergeant Eisenman’s second cousin, Steven Alexis Eisenman, reached out with a correction regarding a statement by Eisenman’s nephew that Israel Eisenman was from the area of Kiev. Steven stated: “The Eisenmans were from Kopaigorod, Podolia Russia. Now known as Kopaihorod, Vinnyts’ka oblast, Ukraine. The village is about 211 miles south-west from Kiev.”

The most authoritative document available to the Eisenman family, based on local records from where Israel was born, places Israel’s birth as 1874. Other records, such as his World War I draft card, gave his birth year as 1877.

Birth Certificate and Register

Curiously, Martin’s birth certificate listed his name as Samuel Eisman. The Wilmington Birth Register apparently had Samuel (or something similar) recorded, but then crossed out and Martin written in. Although generally authoritative, I’ve found that birth records from this era often have spelling variations, especially for children born to immigrants.

1940 Census

The 1940 census stated that Martin was listed as working as a woman’s clothing salesman. Eisenman’s younger brother disputes the accuracy of that entry, though his niece thought that he may have helped his mother’s other business. Eisenman’s nephew recalls that Minnie Eisenman was a milliner and made beautiful women’s hats.

Promotion Date

Colonel Carle’s letter to Etta Eisenman stated that “The records further show that your brother was promoted from private to sergeant on 6 May 1942.” This statement is difficult to believe. If true, it would mean that Eisenman jumped three grades at once—a month after he was captured by the Japanese, no less. The same records that Carle summarized also stated that Eisenman went missing in action on May 7, 1942. The loss of records in the fall of the Philippines obviously complicated things. It would seem that the Army listed unaccounted for personnel in the Philippines as missing after the Japanese captured Corregidor on May 6, 1942. In reality, there is no evidence that Sergeant Eisenman ever went to Corregidor, and he was most likely captured on Bataan on April 9, 1942.

I have no evidence to support the following speculations, but I believe it likely that Eisenman was promoted to sergeant sometime after the beginning of the Pacific War, when routine paperwork could no longer flow to the War Department. Any subsequent unit records were captured or destroyed. If not before, his promotion may have occurred was when the 17th Pursuit Squadron began acting as infantrymen. Given that he had spent two years as an infantryman in Panama, Eisenman would have been better qualified as a squad leader than other members of his unit. If word did not get out based on Eisenman’s promotion, it would have come when the Japanese reported him as a prisoner of war. Lacking the actual date of his promotion, the War Department may have simply decided to make the date precisely one day before he officially was declared missing in action.

Interestingly, 1st Lieutenant Balfanz’s secret roster listed Eisenman in a section of corporals and privates rather than sergeants.

Given the loss of records in the Philippines as well as the probable destruction of Eisenman’s personnel file in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire, it is unlikely that a more detailed service summary than what Colonel Carle compiled in 1946 will ever come to light.

Airfield Assignment/Intercepted Information

In his article “American POWs on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell,” Lee A. Gladwin wrote that of the 750 prisoners who eventually ended up aboard the Shinyo Maru, “Since February 29, 1944, 650 officers and enlistees labored on a Japanese airfield at Lasang. The other 100 had similarly worked on another airfield south of Davao.” The Davao Penal Colony closed in mid-1944, so the men working on the airfields could not return there.

Gladwin wrote that Fleet Radio Unit Pacific had intercepted and decrypted a Japanese message about the convoy. The message was incomplete, indicating that Shinyo Maru had 750 (blank) aboard. The British Radio Unit Eastern Fleet decryption of the same message revealed that it was 750 prisoners of war but reached the Americans too late. Gladwin concluded that “FRUPAC misinterpreted this crucial part of the message with fatal consequences.”

In fact, as Gregory F. Michno’s research indicates, it is doubtful that the mistake altered the outcome in any way:

The Allies often knew the names of the ships carrying POWs, but even so, the submarines could not identify individual ships in a convoy. There were no flags saying “POWs HERE,” and since subs could not get close enough to see ship names, even if not painted out, there was no way to distinguish one from another. They were ordered to go after a convoy. It would not be prudent to mention POWs; it would be counterproductive, would perhaps make the sub captains tentative in their attacks, would raise ethical and moral arguments, and it would open up avenues for possible legal actions by victims seeking reparations.

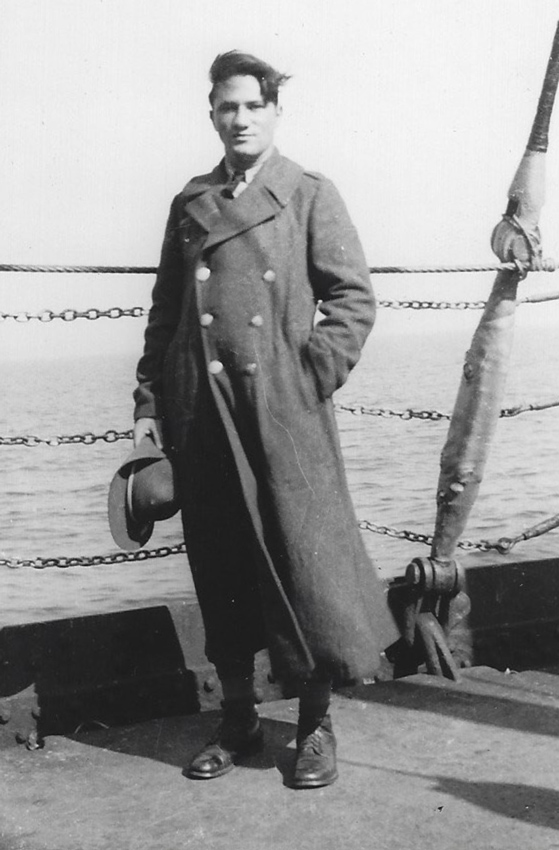

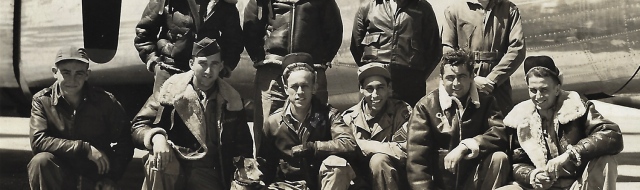

Photo Enhancement

I enhanced the photo at the top of the page using Photoshop and tools on the genealogy website MyHeritage. This software is useful in instances where the only known photograph is of limited resolution (in this case, because the original print was slightly out of focus and damaged). I believe this to be an accurate reconstruction, but the software could potentially introduce errors by misinterpreting fuzzy details in the original photograph. A comparison of the original and enhanced versions of the photos can be viewed below.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Eisenman family for providing extensive information, letters, and photos, and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photos of Sergeants Eisenman and Knudson. Thanks also go out the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware for putting me in touch with the Eisenmans.

Bibliography

Balfanz, A.W., Jr. “17th Pursuit Squadron.” Philippine Archive Collection. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Blanton, Nathaniel H. “Statement Of Activities During The Early Days Of The War.” February 20, 1945. Reel 7501. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Bruegger, Susan Eisenman. Phone interview on December 1, 2021.

Carle, Charles D. Letter to Etta Eisenman, October 21, 1946. Courtesy of the Eisenman family. https://delawareswwiifallen.files.wordpress.com/2021/11/martin-eisenman-service-letter.jpg

“Child Dies of Burns.” Wilmington Morning News, January 31, 1922. Pg. 2. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/89853155/abraham-eisenman-dies/

Chun, Clayton. The Fall of the Philippines 1941–42. Osprey Publishing, 2012.

“City Sergeant Dies in Sinking Of Prison Ship.” Journal-Every Evening, April 26, 1945. Pg. 1 and 25. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/89105785/eisenman-killed-pg-1/, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/89105923/eisenman-killed-pg-2/

Clay, Steven E. U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919–1941, Volume 3. The Services: Air Service, Engineer, and Special Troops Organizations. Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16040coll3/id/199/rec/6

“Davao Penal Colony.” Diaries and Historical Narratives, 1940 – 1945. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/17330693

Davis, Shirley. “Hero Describes Jap Prison Life.” The Desert News, December 14, 1944. Pg. 18. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/89106789/lyle-g-knudson-shinyo-maru-survivor/

Eisenman, Etta. Martin Eisenman Individual Military Service Record, October 23, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18623/rec/1

Eisenman, Martin. Letter to Mrs. McCabe, July 10, 1941. Courtesy of the Eisenman family. https://delawareswwiifallen.files.wordpress.com/2021/11/martin-eisenman-letter.jpg

Eisenman, Norman. Zoom interview on November 14, 2021.

“Israel Eisenman Hurt When Struck by Truck.” Every Evening, September 11, 1931. Pg. 21. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/89856653/israel-eisenman-injured/

Gladwin, Lee A. “American POWs on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell.” Prologue Magazine, Winter 2003. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2003/winter/hell-ships-1.html

Kennedy, Anna. “Statement of Investigation.” John E. Adams, Jr. Individual Deceased Personnel File. National Archives.

La Forte, Robert S., Marcello, Ronald E., and Himmel, Richard L., eds. With Only the Will to Live: Accounts of Americans in Japanese Prison Camps 1941–1945. Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1994.

Michno, Gregory F. Death on the Hellships: Prisoners at Sea in the Pacific War. Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Montgomery, Robert D. “Battle of ‘Agoloma’, Bataan, Philippine Islands, January 1942. Regarding, Company A, 803rd Engineer Batallion [sic] (Avn)(Sep).” June 24, 1946. Reel A0241. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency. https://delawareswwiifallen.files.wordpress.com/2021/10/803rd-engineer-battalion-avn-history-from-a0241.pdf

Morton, Louis. The Fall of the Philippines. Originally published in 1953, republished by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1993. https://history.army.mil/html/books/005/5-2-1/CMH_Pub_5-2-1.pdf

Obert, David L. “Activities of Fighter Units in the Philippines.” Circa 1945. Reel 7501. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

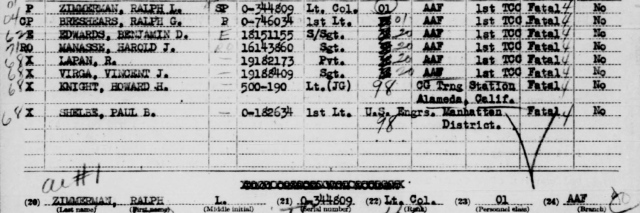

“Roster of Allied Prisoners of War believed aboard Shinyo Maru

when torpedoed and sunk 7 September 1944.” https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/ShinyoMaruRosterJPW.html

Samuel Eisman birth certificate. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware.

Sheppard, William A. and Gilmore, Edwin B. “Narrative Statement by Lt. Col. W.A. Sheppard and Maj. E.B. Gilmore.” November 1, 1944 – February 1, 1945. Reel A0723. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Silverman, Lowell. “Private 1st Class John E. Adams, Jr. (1921–1944).” https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2021/11/06/private-1st-class-john-ernest-adams-jr/

“Two Soldiers From Wilmington Are Reported Prisoners of War.” Journal-Every Evening, September 8, 1943. Pg. 3. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/89057716/eisenman-pow/

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531892_00760

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00551-00028

U.S. Army Enlisted and Officer Rosters, July 1, 1918 – December 31, 1939. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-RSYP-Z (April 1935), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-R3QN-B (January 1936), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-RSBY-1 (April 1936), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-R37W-J, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-RSFZ-D (November 1936), https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-RS13-7 (April 1937)

U.S. Army Transport Service Passenger Lists. Record Group 92. National Archives. https://www.fold3.com/image/604332482

Wilmington Birth Register, 1916. Record Group 1500.205. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware.

World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005207041_04239

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=06855191&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=248967

Last updated on December 3, 2021

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.

Israel Eisenman was not from Kiev, it was just the usual point of exit from Russia at the time. The Eisenmans were from Kopaigorod, Podolia Russia. Now known as Kopaihorod, Vinnyts’ka oblast, Ukraine. The village is about 211 miles south-west from Kiev.

LikeLike

Thanks, I added that information to the Notes section entry about Israel Eisenman.

LikeLike

I’d be interested in the source of a “birth certificate”. Jews in a Shetl in Czarist Russia?

The only reference I came across to “Kiev” was on a census form when the family lived on East 7th st, Probably the only place the census taker could spell. Oddly, the census forms often just said “Russia-Yiddish” as place of birth.

I believe Kiev was a “family memory”

LikeLike