| Hometown | Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Career soldier |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | O-15081 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Philippine Chemical Warfare Depot |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Legion of Merit, Bronze Star | Battle of Bataan |

Early Life & Family

Louis Edward Roemer was born on March 26, 1901, at 701 Madison Street in Wilmington, Delaware. He was the third child of Frederick Roemer (1870–1907) and Louisa Roemer (née Hill, 1878–1952). His father, known as Fred, was a German immigrant who worked as a saloonkeeper. He was also a volunteer fireman for the Water Witch Steam Fire Engine Company No. 5, prior to the foundation of the career Wilmington Fire Department. He died on November 10, 1907, from cirrhosis of the liver, when Roemer was six.

Roemer had an older brother, Frederick “Fred” Carl Roemer, Jr. (1898–1959), an older sister, Helen Roemer (1899–1955), and two younger brothers, Francis Hill Roemer (1902–1964) and John George Roemer (1904–1987).

Roemer was recorded on the census in April 1910 living at 219 North Rodney Street in Wilmington with his mother, four siblings, and his uncle, Louis Hill. At the time of the next census in January 1920, Roemer was living with the same six people at 807 Harrison Street.

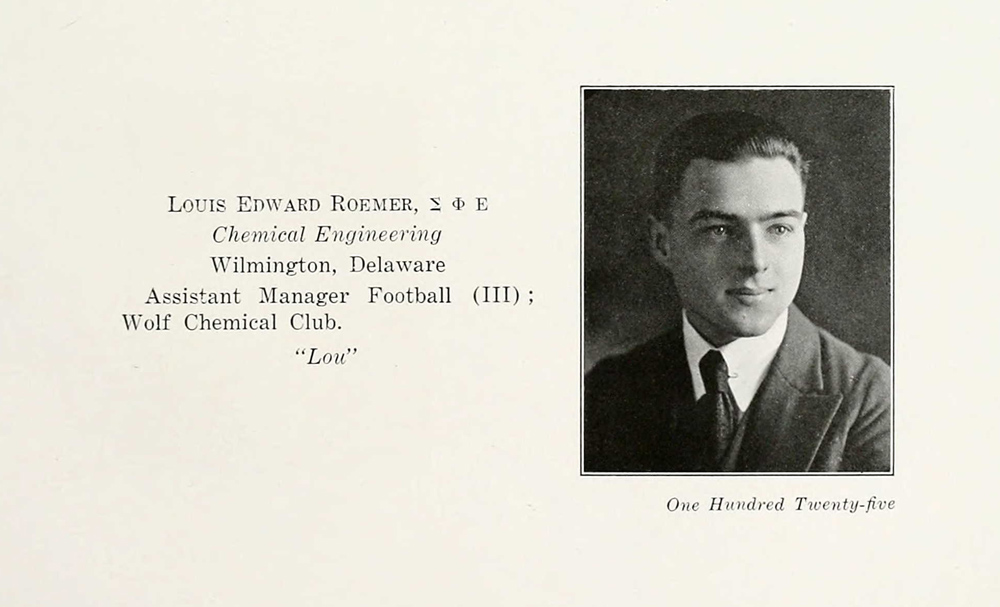

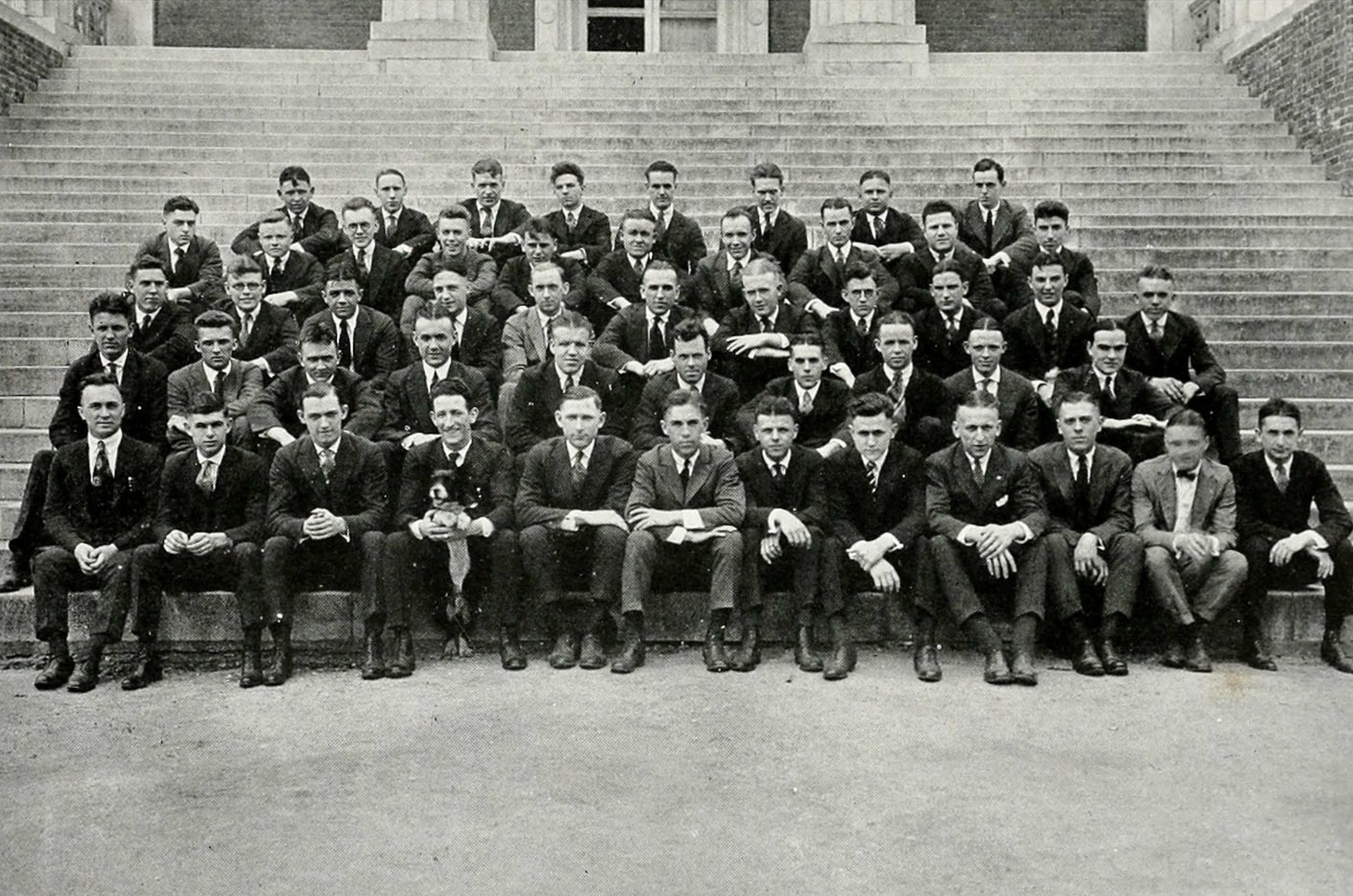

After graduating from Wilmington High School on June 26, 1918, Roemer enrolled at the University of Delaware in Newark. Roemer’s junior yearbook stated that “Lou” was assistant manager of the university football team, a member of the Wolf Chemical Club, and in the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity. He was manager of the team during his senior year. On June 12, 1922, he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Chemical Engineering.

Roemer’s older brother, Fred, was in the Students’ Army Training Corps at the end of World War I. His younger brothers also served during World War II: Francis in the U.S. Army and John in the Marine Corps.

Interwar Military Career

Roemer was cadet in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps at University of Delaware, which had an Infantry program at the time. A June 1, 1922, article in The Evening Journal mentioned that Roemer was a cadet 2nd lieutenant shortly before his graduation. However, the program was not his pathway to a commission, at least not directly. The Wilmington Morning News reported on January 27, 1923, that Roemer and two other “former students of the University of Delaware were among the successful candidates, as a result of the examination conducted October 23, 1922, which the Secretary of War today recommended to the President for nomination for commissions as second lieutenants in the regular army.”

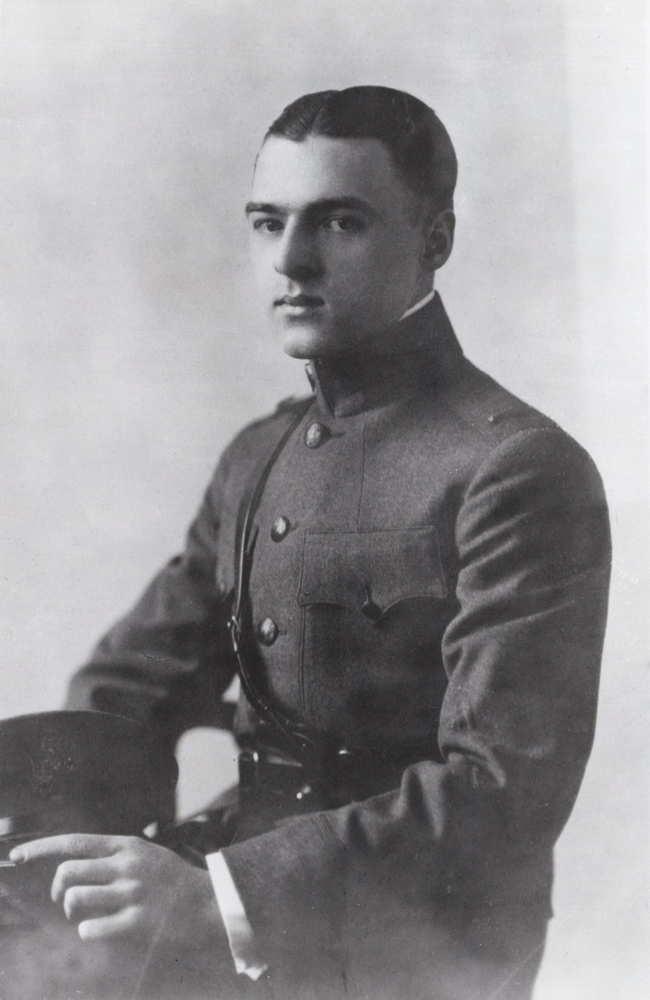

Roemer was described as a resident of Edgemoor, Delaware, when he accepted a commission as a 2nd lieutenant in the U.S. Army Infantry on February 10, 1923, with a date of rank of January 5, 1923. Although Roemer gained prominence as an officer in the Chemical Warfare Service during World War II, that was his branch only for the last quarter of his long career.

A roster for Headquarters Fort Thomas, Kentucky, reported that Roemer was assigned to the 10th Infantry, 5th Division on February 18, 1923, but had not yet joined. He arrived at Fort Thomas on March 9, 1923. There, he was assigned to Company “H,” 10th Infantry Regiment, though he did not immediately join it.

On April 21, 1923, 2nd Lieutenant Roemer joined Company “H” at Camp Knox, Kentucky. At the time, there was only one other officer in the company. All the noncommissioned officers and many of the other enlisted men had reenlisted in the U.S. Army after serving in World War I. The interwar U.S. Army was small, with anemic funding, and advancement could be painfully slow by modern standards.

2nd Lieutenant Roemer went on detached service at Camp Perry, Ohio, from August 24, 1923, until rejoining his company—now stationed at Fort Thomas—on September 28, 1923. Roemer and his unit returned to Camp Knox on April 10, 1924. They headed back to Fort Thomas on August 3, 1924. Roemer went on leave on October 13, 1924, returning to duty on November 12.

Roemer departed the 10th Infantry on February 28, 1925, after he was transferred to the Philippine Department. At the time, the Philippine Islands were an American possession, conquered during the Spanish–American War of 1898 and subsequent Philippine–American War.

On March 4, 1925, Roemer sailed aboard an Army transport, U.S.A.T. Chateau Thierry, from New York to San Francisco, California, via the Panama Canal. In San Francisco, he transferred to U.S.A.T. Thomas, shipping out on March 24, 1925. After intermediate stops in Honolulu, Hawaii, and Guam, the ship arrived in Manila, Philippine Islands. On April 18, 1925, 2nd Lieutenant Roemer joined Company “M,” 45th Infantry (Philippine Scouts), Philippine Division, at Fort William McKinley, southeast of Manila.

Although part of the U.S. Army, the Philippine Scouts had Filippino enlisted men with largely American officers. On February 20, 1926, Roemer went on detached service to the Bataan Peninsula, where he would fight the Japanese some 16 years later. He returned to Fort McKinley on April 14.

On April 18, 1927, the two-year anniversary of his arrival in the Philippines, 2nd Lieutenant Roemer went on detached service to Camp John Hay. Located in the highlands near Baguio, east of Lingayen Gulf in central Luzon, the camp was renowned for its pleasant climate and Roemer may have been there for rest and recreation. At the end of World War II, Yamashita Tomoyuki (1885–1946), the Japanese commanding general in the Philippines, surrendered there. Roemer returned to Company “M” on May 17, 1927.

Roemer was promoted to 1st lieutenant on October 11, 1927. A few months later, he was transferred to the 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Division at Fort Screven, Georgia, per Special Orders No. 6, Headquarters Philippine Department, dated January 11, 1928. He left the 45th Infantry on February 15, 1928. After three years overseas, he arrived in San Francisco, on March 17, 1928.

On or about March 21, 1928, Roemer sailed from San Francisco aboard U.S.A.T. Cambrai, bound for New York via the Panama Canal. It appears that he went on leave prior to reporting to Fort Screven, since he did not join the 8th Infantry until July 10, 1928. In addition to his other duties, he served as post exchange officer.

On September 25, 1928, 1st Lieutenant Roemer joined Company “D,” 8th Infantry. He remained with the company until June 7, 1929. That same month, he joined Company “C.”

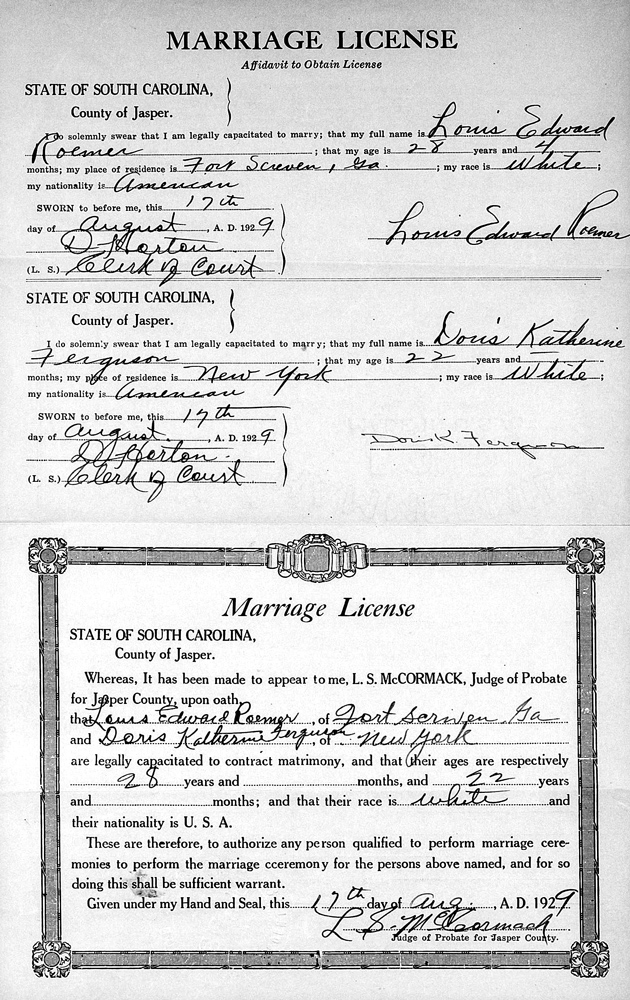

August 1929 was an eventful month for Roemer. According to newspaper articles—the story was gleefully picked up by the Associated Press in 1931—Roemer met Doris K. Ferguson (1906–1991), apparently at a party in Ridgeland, South Carolina, about 30 miles north of Fort Screven. Ferguson, a beautiful 20-year-old woman from Paterson, New Jersey, was described in 1934 by her hometown paper, The Morning Call, as “prominent among the younger social set of this city[.]”

Jack Miley wrote in the Daily News that after the party, “somebody suggested that she take part in a mock wedding with Louis E. Roemer[.]” On August 27, 1929, the couple was married by the county clerk in Jasper County, South Carolina. Miley continued:

A few days later Miss Ferguson learned she was legally married to Roemer. The clerk, whom she thought was not empowered to perform marriages, had spliced them according to law.

The young woman was horrified. As a staunch member of St. Joseph’s Catholic church in Paterson, she did not recognize divorce as a solution to her difficulties.

In early January 1931, when Ferguson was working as a teacher and Roemer was also a New Jersey resident while training at Fort Monmouth, she tried to get an annulment. “Our marriage was only a lark,” she was quoted as arguing, “and I want to be released.” The Daily News reported on June 21, 1931, that she had “obtained a final decree of divorce from her husband, Louis E. Roemer of 424 River Road, Red Bank, in Supreme Court” though “Roemer said that his wife had been guilty of fraud because she did not let him know of her intentions not to live with him.” It is unclear whether Roemer really felt spurned by her actions; he was listed as single in the 1930 census.

The tale ended happily for Ferguson, who evidently was able to secure a religious annulment as well. The Morning Call reported that on December 22, 1934, she married Albert Hibbs Tomlinson (1896–1975) at St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic rectory and then departed the Great Depression-stricken country for a yearlong around-the-world honeymoon.

Shortly after his disputed marriage, on August 26, 1929, Roemer went on leave prior to his transfer to The Infantry School, Fort Benning, Georgia. He arrived at Fort Benning on September 20, 1929, to take the Company Officer’s Class 1929–30. The faculty at that time included Lieutenant Colonel George C. Marshall (1880–1959), later the U.S. Army chief of staff during World War II and postwar secretary of state.

After nearly a year of training at Fort Benning, Lieutenant Roemer arrived at Signal School, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, on September 8, 1930, to begin another training class. On June 15, 1931, he completed the Communication Officers’ Course. Three days later, he was transferred to the 12th Infantry, 4th Division at Fort Howard, Maryland, which guarded the entrance to Baltimore Harbor. He took some leave before reporting for duty on June 23. That day, he joined Headquarters Company, 12th Infantry, which he assumed command of on June 26. He was also assigned the duty of post signal officer at Fort Howard.

On October 12, 1931, another Delawarean, Captain John Wilson “Iron Mike” O’Daniel (1894–1975), newly arrived from the Hawaiian Department, replaced Roemer as commander of Headquarters Company, 12th Infantry. Roemer remained assigned to duty with Headquarters Company as well as the post signal officer. Another officer who arrived at Fort Howard that fall was Captain Louis D. Hutson (1893–1962), who assumed command of Company “A,” 12th Infantry on September 21, 1931. During World War II, Hutson, by then a colonel, became a prisoner of the Japanese and would later recall an act of kindness that Roemer did for him in the dark days after the American surrender in the Philippines.

1st Lieutenant Roemer went on leave December 31, 1931, returning to duty on January 3, 1932. He was on detached service at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, during the entire month of February 1932. On March 25, 1932, Roemer assumed command of Headquarters Company, 12th Infantry when Captain O’Daniel went on leave and subsequently took ill. Roemer took a day of leave on April 2, 1932, and relinquished command of the company to Captain O’Daniel on April 4. Roemer’s unit relocated to Fort George G. Meade on May 13, 1932, but returned to Fort Howard on May 28.

On July 28, 1932, 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry, then stationed at Fort Washington, Maryland, was involved in the controversial suppression of the Bonus Army. Also known as the Bonus Expeditionary Force, they were World War I veterans who had come to Washington, D.C., clamoring to redeem certificates that the government would not pay out before 1945. A riot broke out after the Metropolitan Police began to clear veterans who were squatting in government buildings, exacerbated when a police officer gunned down two veterans. President Hoover authorized a military response that would end up being carried out by a number of U.S. Army officers who were either already famous from World War I or who would rise to prominence during World War II: U.S. Army chief of staff, General Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964), Major Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), Major George S. Patton, Jr. (1885–1945), and Captain Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. (1895–1965). Infantrymen accompanied by cavalry and five tanks, drove the veterans back at bayonet point, though without inflicting any additional fatalities.

That same day, men in the 12th Infantry stationed at Fort Howard, including Roemer’s Headquarters Company, moved to Fort Myer, Virginia, adjacent to Arlington National Cemetery, as a reserve force if the violence escalated, though that ended up being unnecessary. The 12th Infantry headed back to Fort Howard two days later, on July 30.

1st Lieutenant Roemer assumed command of Headquarters Company from August 22–28, 1932, while Captain O’Daniel was on leave. Part of the regiment, including Headquarters Company, moved to Fort George G. Meade on September 17, 1932. Headquarters Company returned to Fort Howard on October 10. The March 1933 roster indicated that the duty of engineering officer had been added to Roemer’s portfolio, but only briefly. On April 20, 1933, he was relieved of the signal and engineering duties and placed in charge of Company 324 (White), Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.). His unit was alternatively known as the 324th Company, C.C.C. Roemer temporarily continued his duties with Headquarters Company while Company 324 was based at Fort Howard. Captain O’Daniel left the 12th Infantry at the end of the month.

The C.C.C. was part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal in response to the Great Depression. Companies were organized along paramilitary lines and commanded by military officers. The C.C.C. employed down-on-their-luck young men, using them to accomplish public works projects and in some cases giving them vocational training.

Lieutenant Roemer married Mary Davis Learn (née Mary Virginia Davis, 1902–1969) on May 6, 1933. The Long Branch Daily Record reported: “The ceremony took place in the Presbyterian Manse at Ellicott City, Md.,” adding that Roemer’s bride “has been head of the filing department of the Sigmund Eisner Company at Red Bank” in New Jersey. He became stepfather to her son, Ralph Stanley Learn (1920 or 1921–2007), who served as a pilot in the Army Air Forces during World War II. Unit records suggest the couple did not have a honeymoon, since Roemer did not take any leave that month, though his bride did accompany him on a move to western Maryland later that month.

Roemer was released from duty with Headquarters Company, 12th Infantry effective May 20, 1933. The following day he was placed on detached service at the C.C.C. Camp, Green Ridge State Forest, Maryland. The Sun reported that on the morning of May 22, 1933, following an overnight journey by train and road, Company 324 arrived at their new camp. The paper added that

the tent city did not rise as rapidly as enlisted men could have erected it, and getting the supply trucks over Fifteen-Mile creek, which runs by the camp, took time. It seemed like a stroke of genius when Lieutenant Roemer finally brought order out of the chaos.

The article also mentioned one or Roemer’s rules for his men: “When you want to cuss, whistle.”

The C.C.C. file for Morris Weinberg (1911–1994) provides some glimpses into Roemer’s leadership style at the time. A young Jewish man from Baltimore, Weinberg had previously attempted to enlist in the U.S. Navy but failed the physical due to a hernia. He did not disclose the condition during his C.C.C. physical—he claimed he was not asked and the doctor did not notice it—but in a labor company like the 324th, it soon became a problem. To make matters worse, he was mistreated by other men in his unit. Lieutenant Roemer later testified at a hearing:

On the morning of June 14, 1933 I called Morris Weinberg into the orderly tent and told him that I knew he was being annoyed and teased by other members of the Company, and that he should not pay any attention to them; to go ahead and do his work and that I would take care of him. […] Three hours later I was informed that he had deserted, carrying with him a lot of equipment. The next morning he reported back stating that he was present for duty and that he had lost a lot of clothing equipment off of a truck on which he was riding. I told him that although he admitted stealing this Government property that I would give him a chance to work it out. He said he would be glad to do this.

Soon, however, the pain from his hernia became unbearable and Weinberg had no choice but to come clean. He was in a bad situation given that he had not been forthcoming about a preexisting condition, not to mention going absent without leave and losing equipment. On July 5, 1933, Roemer convened a board of officers which found that although Weinberg “had potential Hernia before enrollment at Fort Howard,” his present illness “was precipitated by work at this Camp” “in line of duty and not the result of his own misconduct.” The board recommended that Weinberg “be sent to the Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington D.C. for repair of Hernia at government expense.” He was transferred to Walter Read two days later, though it is unclear if he had the surgery before returning to camp on July 14. Weinberg was honorably discharged from the C.C.C. on July 17, 1933, due to disability, but did another stint in 1935 and served in the U.S. Army during World War II.

When Roemer returned to duty with Headquarters Company, 12th Infantry—now part of the 8th Division rather than the 4th—at Fort Howard on December 14, 1933. The following year, with his wife now in the advanced stages of pregnancy, Roemer went on leave beginning on June 29, 1934. On July 5, 1934, in Washington, D.C., she gave birth to the couple’s only child, Louis Edward Roemer, Jr. Lieutenant Roemer returned to duty soon afterward. The following month, from August 2–13, 1934, he went on detached service at Camp Holabird in nearby Baltimore for C.C.C. work. Available records are incomplete, but it appears that in September 1934 Roemer’s unit moved to Fort Hoyle, Maryland, and then Fort George G. Meade in early October, before returning to Fort Howard on October 13, 1934.

Roemer went on leave on November 30, 1934, staying at the Officer’s Club at Fort Monmouth. Effective December 14, 1935, he was transferred to the Panama Canal Zone. According to census records and a return passenger manifest, Roemer’s wife, son, and stepson lived with him in Panama.

On December 23, 1934, 1st Lieutenant Roemer joined Headquarters Company, 14th Infantry, at Fort Davis, on the Atlantic side of the Panama Canal Zone. On February 25, 1935, he took on the addition duty of recruit instructor. He was released from that duty on March 6. At the end of the month, on March 31, 1935, Roemer left on detached service to Fort Clayton, on the Pacific side of the canal. A roster noted that he went “via Jungle Route” suggesting he traveled overland rather than by boat. He returned to Fort Davis on April 4, and was sick in quarters April 16–25.

1st Lieutenant Roemer assumed command of Headquarters Company, 14th Infantry on May 14, 1935. He was sick in quarters June 20 through July 2. Roemer went on detached service again during July 16–21, doing “Jungle trail reconnaissance” at Bocas del Toro.

Roemer was promoted to captain on August 1, 1935. Any celebration over the promotion may have been tempered by the fact that he was sick in quarters for three days afterward. The next 19 months passed uneventfully at Fort Davis.

On March 12, 1937, Captain Roemer took on the additional duty of post inspector. On April 21, 1937, Captain Roemer was transferred to the 11th Infantry Regiment, 5th Division, at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana. He was authorized travel time and a lengthy leave before reporting. Roemer and his family boarded U.S.A.T. Chateau Thierry that day, arriving in Brooklyn, New York, on April 27, 1937. He began his leave two days later, with authorization to visit 58 East River Road, Rumson, New Jersey.

After nearly four months of leave, on August 26, 1937, Captain Roemer arrived at Fort Benjmain Harrison and assumed command of Company “E,” 11th Infantry. The 11th Infantry moved to Fort Knox on May 2, 1938, before returning to Fort Benjamin Harrison on May 28.

Roemer went on detached service at Fort Knox during June 12–17, 1938, for the 10th Brigade School of Arms. Due to the absence of many of his regiment’s field grade officers, Roemer also commanded 2nd Battalion from August 11, 1938, to September 2, 1938. Captain Roemer went on detached service at Fort Knox again during September 2–25, 1938, “in connection with 2nd Army CP Exercises.” During October 23–29, 1938, he was on detached service at Wright Field, Ohio, “in connection with Air Corps training for ground officers.”

Most of the 11th Infantry, including Roemer, moved to Fort Knox again on May 1, 1939, but returned to Fort Benjamin Harrison on May 27. On June 10, 1939, Captain Roemer went on detached service to Fort Knox for the Fifth Corps Area School of Arms. He returned to duty with the 11th Infantry on June 15.

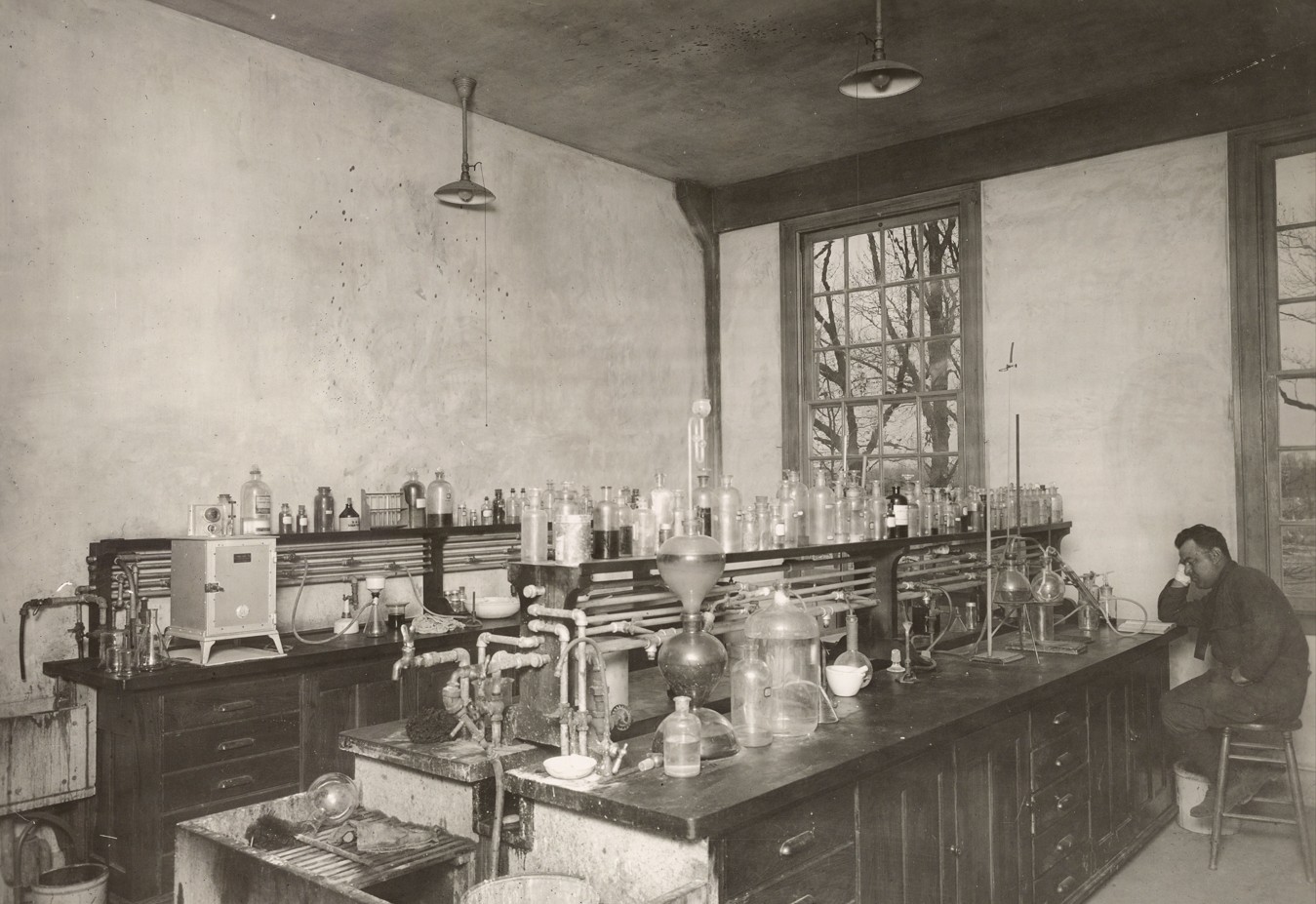

In 1939, Roemer was ordered to return to the Philippines and scheduled to sail from New York City on September 12, 1939. These orders were revoked. Instead, on June 16, 1939, Captain Roemer transferred from the Infantry to the Chemical Warfare Service (C.W.S.) and was reassigned to Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland. However, he was attached to—and continued serving as commanding officer of—Company “E,” until June 21, 1939, when he was attached to Headquarters & Band, 11th Infantry. He was detached from the 11th Infantry on July 1, 1939, and joined Headquarters Edgewood Arsenal.

The C.W.S. originated during World War I, which saw the first widespread use of chemical weapons in combat. In the years leading up to World War II, American policy was to use poison gas only in retaliation for first use by the enemy. The Axis never used gas weapons against American forces and the C.W.S. was limited to secondary roles during the war, such as using generating smoke screens to shield friendly units from enemy view and employing 4.2-inch chemical mortars to fire high explosive and white phosphorous rounds instead of poison gas.

By August 1, 1939, Roemer was attached to Headquarters & Headquarters Company, 2nd Separate Chemical Battalion, at Edgewood Arsenal. He had a full portfolio, including commanding the 412th Chemical Depot Company from August 8, 1939, to October 9, 1939, and commanding the 2nd Separate Chemical Battalion for several stretches: August 1, 7–12, and 20–28, and September 13–14, 1939. In his book, U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919–1941, Steven E. Clay wrote: “The 2nd Chemical Battalion was located at Edgewood Arsenal and performed duties as the support unit for the C.W.S. school.”

On October 15, 1939, Captain Roemer began taking a class as a student at the Chemical Warfare School at Edgewood. He completed his training class on December 1, 1939. The following day, December 2, 1939, he was detached from the 2nd Separate Chemical Battalion. The same day, he was made chief of the Inspection & Safety Division and the Proof Division. An official postwar U.S. Army C.W.S. history, The Chemical Warfare Service: From Laboratory to Field, offers insight into that assignment:

One of the greatest difficulties of the period was meeting the need for trained inspectors. In the peacetime years all CWS inspection was carried on at Edgewood Arsenal under the supervision of the Inspection, Safety, and Proof Division. Inspection was on a 100 percent basis; that is, every major component was inspected on the manufacturing line and later each finished end item was inspected. In addition to the inspection of items being manufactured, there was a program of surveillance inspection under which chemical warfare matériel was periodically checked to determine the extent of its stability. This was done by making spot checks on matériel from a pilot or production plant or by conducting periodic tests on stocks in storage. Both the technicians and inspectors at Edgewood were vitally interested in these data.

If those responsibilities were not enough, the same day two additional duties were added to Major Roemer’s portfolio. He became the base’s survey officer, and commanding officer of a detachment from the 6th Field Artillery. Then, on December 22, 1939, Roemer was also designated the acting signal officer at Edgewood Arsenal, though he only performed that duty until January 12, 1940.

Roemer was promoted to major on July 1, 1940. He remained the chief of the Inspection & Proof Division and the post survey officer but relinquished his positions as chief of the Safety Division and commander of the detachment from the 6th Field Artillery. Later that month, on July 22, 1940, Journal-Every Evening reported that although he was still serving at Edgewood Arsenal, “Major Roemer has been assigned to duty with the 45th Infantry of the Philippine Scouts.” Rosters indicate that transfer never took place.

In September 1940, Major Roemer was appointed trial judge advocate, meaning he would have been the prosecutor for any general court-martials held at Edgewood Arsenal. In December 1940, that role was dropped, though he remained a member of the court.

Officer rosters from Headquarters Edgewood Arsenal from 1941 went missing before they could be microfilmed, but on March 18, 1941, Major Roemer was transferred to the 9th Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He was authorized leave prior to reporting, joining the division on March 31, 1941. On August 28, 1941, he went on detached service for what was supposed to be 30 days at Edgewood Arsenal. Another entry on September 27, 1941, initially stated that he was taking a leave of absence, but that was crossed out and detached service written in, without specifying where he was performing it. The issue of Army and Navy Journal dated September 13, 1941, stated that Major Roemer was being transferred “from Ft. Bragg, N. C., to Philippine Dept., sail 4 Oct., San Francisco, Calif.” Indeed, a Headquarters 9th Division morning report dated October 4, 1941, documented that Major Roemer had been transferred to the Philippine Department.

Unlike his tour in Panama, there was no possibility of Major Roemer’s family accompanying him to the Philippines. Earlier that year, in response to increased tensions with the Japanese, the U.S. Army had begun evacuating soldiers’ dependents.

Defense of the Philippines

Much had changed in Philippine Islands since Major Roemer’s first tour of duty there in the mid-1920s. The archipelago was still an American possession, but the U.S. had promised to grant the Filipinos independence in 1946. Toward that end, the Americans established the transitional Commonwealth of the Philippines and Philippine Army, while retaining the Philippine Scouts within the U.S. Army.

Americans and Filipinos alike watched Japan with wariness. 1941 was four years into the latest Sino-Japanese War, aggression opposed by the Roosevelt administration. Capitalizing on the defeat of France in 1940, Japanese advances into French Indochina precipitated sanctions by the U.S., most notably cutting off scrap metal and oil exports that were vital to both its economy and war machine. Negotiations proved fruitless and by the time Roemer arrived back in the Philippines, it was clear that Japan would have to either cave to American demands and abandon its expansionist campaign or double down by seizing the raw materials it needed by force.

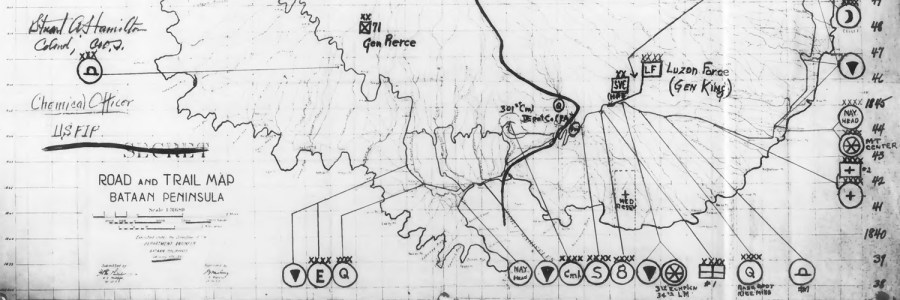

Per Special Orders No. 248, Headquarters Philippine Department, dated October 23, 1941, Major Roemer was assigned to the Philippine Chemical Warfare Depot, Fort Mills, on the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay. In addition to being commanding officer of the depot, Roemer was also attached to Headquarters Philippine Department for duty, where he served as assistant chemical officer under Colonel Stuart Adams Hamilton (1893–1956), chemical officer, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East. A 1916 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Hamilton served only briefly in the U.S. Navy before accepting a commission in the U.S. Army. He initially served in the Coast Artillery Corps before switching to the C.W.S. in 1926.

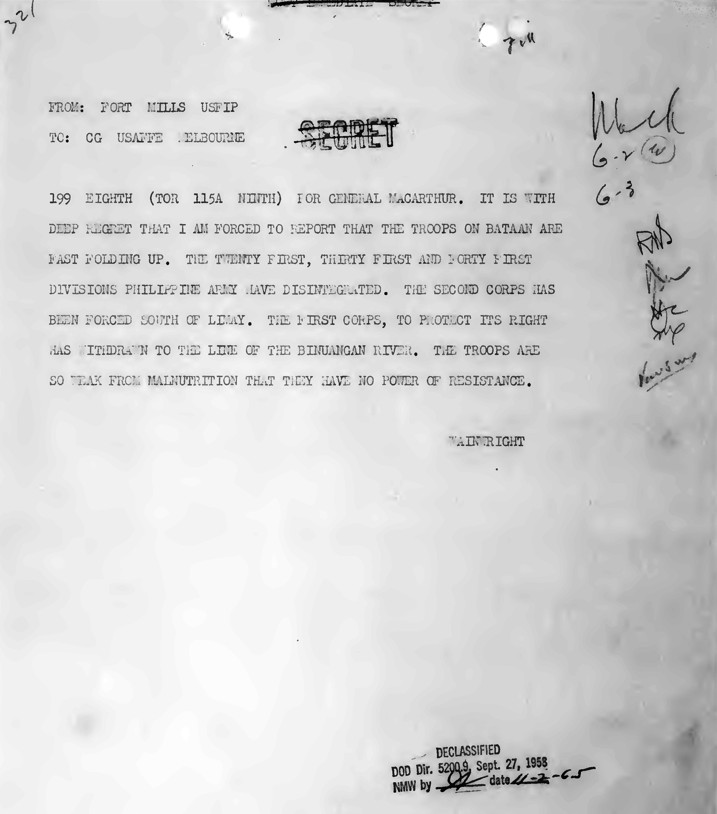

Many American military records were lost in the fall of the Philippines, some destroyed by Roemer’s own orders. However, his role is well-documented because Colonel Hamilton managed to dispatch a report on C.W.S. activities during the campaign about three weeks before the American surrender, which he later curated and expanded in 1946.

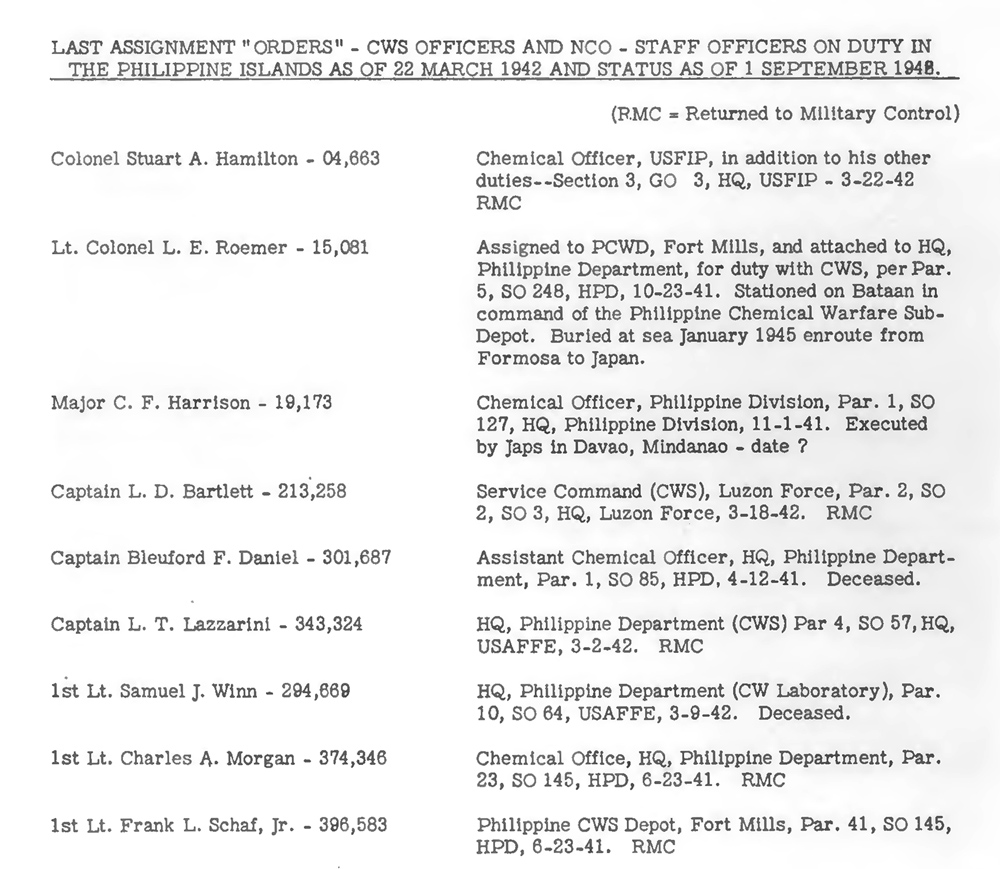

The C.W.S. had very few men in the Philippines. Colonel Hamilton later recalled that when the Pacific War began, there were only 14 American C.W.S. officers and 275 C.W.S. American enlisted men, plus 12 Philippine Scouts. Most of the enlisted men were in chemical units in the Far East Air Force. The nascent Philippine Army had no chemical units at all, although soon after Pearl Harbor the 301st Chemical Depot Company (Philippine Army)—also known as the 301st Chemical Company (Depot)—was activated, adding four officers and 70 enlisted men, though they had very little training.

On December 8, 1941—shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, which was on the other side of the International Date Line—the Japanese launched an offensive against British, Dutch, and American possessions in the eastern Pacific, including the Philippines. The outbreak of war saw the Philippine Department’s gas masks stored in warehouses at Manila. Major Roemer’s first job was supervising the stockpiling and issue of gas masks at Fort William McKinley.

At the outbreak of war, neither the Americans nor the Japanese knew if their enemies planned to use chemical weapons. Both sides decided against using poison gas during the campaign, meaning C.W.S. efforts to distribute gas masks and anti-gas impregnated clothing ended up being largely pointless. Evidently to prevent the possibility of provoking reprisals, General MacArthur’s headquarters went so far as to ban the use of white phosphorus munitions, smoke pots, and tear gas effective January 3, 1942.

C.W.S. contributions to the Allies in the Philippines campaign included manufacturing Molotov cocktails for combat, sulfuric acid for use in batteries, thiamine supplements to treat or prevent beriberi, and bleach for sanitation. C.W.S. officers also developed an improvised flamethrower, researched quinine substitutes, evaluated captured Japanese chemical equipment, and repurposed existing American equipment and supplies to purify drinking water.

Japanese amphibious forces began landing on Luzon on December 10, 1941. Although the prewar War Plan Orange-3 called for a withdrawal to the Bataan Peninsula if the Japanese invaded the Philippines, few supplies had been stockpiled there. In the case of the C.W.S., its only completed storehouse was the one under Roemer’s command, the Philippine Chemical Warfare Depot on Corregidor. Eight more chemical supply warehouses were under construction on Luzon, all of them in locations that the Americans would cede to the Japanese in the first weeks of the campaign. War Plan Orange-3 provided for two C.W.S. subdepots on Bataan but construction had not started on either one.

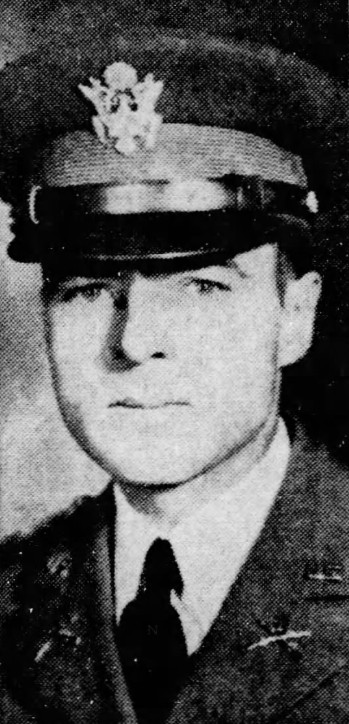

On December 19, 1941, Roemer was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the Army of the United States, though word did not reach the Philippines until the following month.

General MacArthur delayed executing War Plan Orange-3 until two weeks into the invasion, on Christmas Eve 1941, in the vain hope that American and Filipino forces could halt the Japanese without handing them most of the archipelago. The C.W.S. journal recorded that morning that “Roemer left with a convoy of supplies for Bataan at 9:00 AM.” Accompanied by Filipino soldiers from the 301st Chemical Depot Company, he found the planned site for the C.W.S. depot on the peninsula already occupied. He would have to look elsewhere.

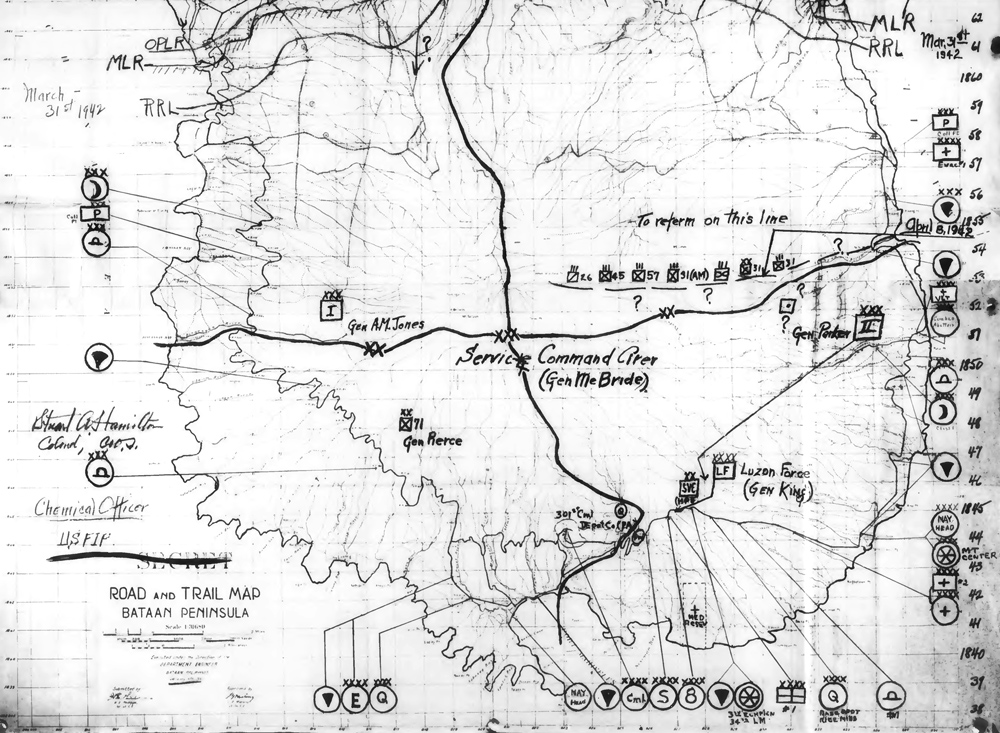

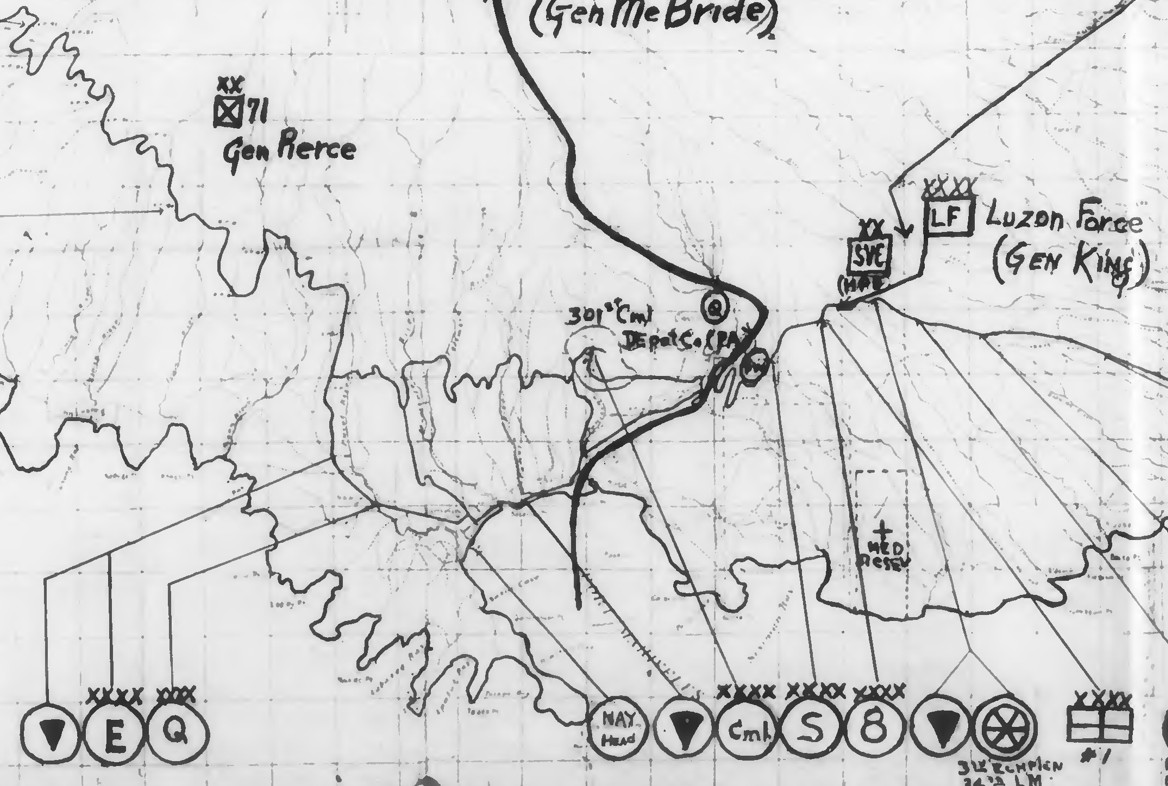

The interior of Bataan was mountainous, so its two main north–south roads hugged the coasts, meeting at Mariveles, the port and base at the southern tip of the peninsula. Both roads were also connected by the Mariveles Cut-off Road north of Mariveles. It was here that Roemer developed the C.W.S. depot “at Km Post 175.8 Mariveles Cut-off Road[.]”

Forces evacuating to Bataan had no choice but to abandon food and equipment that would be desperately needed in the months ahead. Indeed, during the first week in January 1942, the defenders’ rations were drastically reduced to conserve what remained. Still, until the Japanese captured Bataan and the island fortresses in Manila Bay, the vital port of Manila was useless for their war machine.

On December 31, 1941, with the Japanese arrival in the Manila area imminent, one last convoy of C.W.S. personnel returned to Fort McKinley on Roemer’s orders. They recovered as many gas masks and cans of gasoline as their trucks could carry and then burned down the warehouses before returning to Bataan.

A C.W.S. journal entry dated January 10, 1942, stated that 1st Lieutenant Charles Allison Morgan, Jr. (1917–1984) “went to Bataan tonight to check with Major Roemer regarding the division of CW supplies and equipment between Fort Mills and Bataan. The amount stored at each place will be governed by the number of troops stationed thereat.”

The following night, Morgan returned to Fort Mills with “a Japanese gas mask captured on the previous day. Major Roemer sent over a free translation of characters on the various parts of the mask.”

The C.W.S. journal recorded that on January 14, 1942, the day after word arrived about Roemer’s promotion, “Lt. [Frank L.] Schaf went to Bataan tonight to confer with Col. Roemer re CW supplies. The Depot at Bataan is assembling equipment and filling quantities of anti-tank mines for the forces there.”

According to the citation for the Legion of Merit posthumously bestowed upon Roemer and quoted in the Red Bank Register:

Lieut. Col. Louis E. Roemer performed exceptionally meritorious service from 7 December, 1941, to 9 April, 1942, as assistant chemical officer, Philippine Department, Commanding Officer, Chemical Warfare Depot on Bataan, and Instructor, 301st Chemical Depot Company (PA. [Philippine Army]). The Chemical Warfare Depot, under his direction, improvised a method of manufacturing incendiary grenades, devised a means for the field impregnation of clothing and developed a mobile repair shop for travel to the forward areas for repair of Chemical Warfare equipment.

He also directed and supervised the emergency field manufacture on Bataan of liquid bleach which was used extensively as a disinfectant in combating diseases and pestilence. He participated in many patrol actions and trained the 301st Chemical Depot Company (PA.) as a combat unit. By his unceasing efforts, inspiration leadership and tenacity of purpose, Col. Roemer contributed materially to the defense of the Philippine Islands.

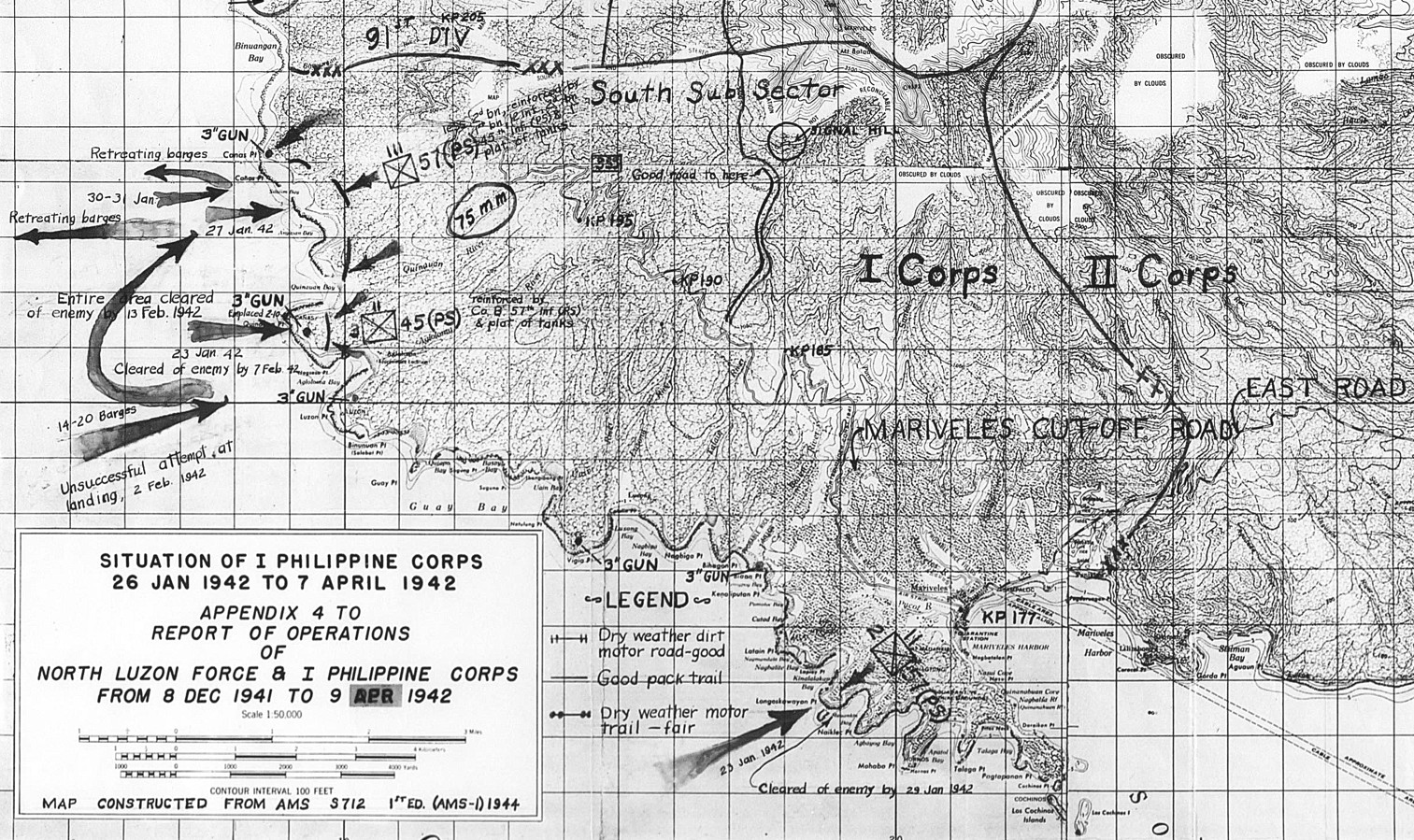

American and Filipino defensive lines on Bataan held against repeated Japanese assaults. Frustrated, beginning the night of January 22, 1942, the Japanese attempted an amphibious operation to land two battalions on the southwest side of the Bataan Peninsula. The attack was poorly planned and executed, but with largely rear echelon personnel in the area, the two enemy battalions were still a serious threat.

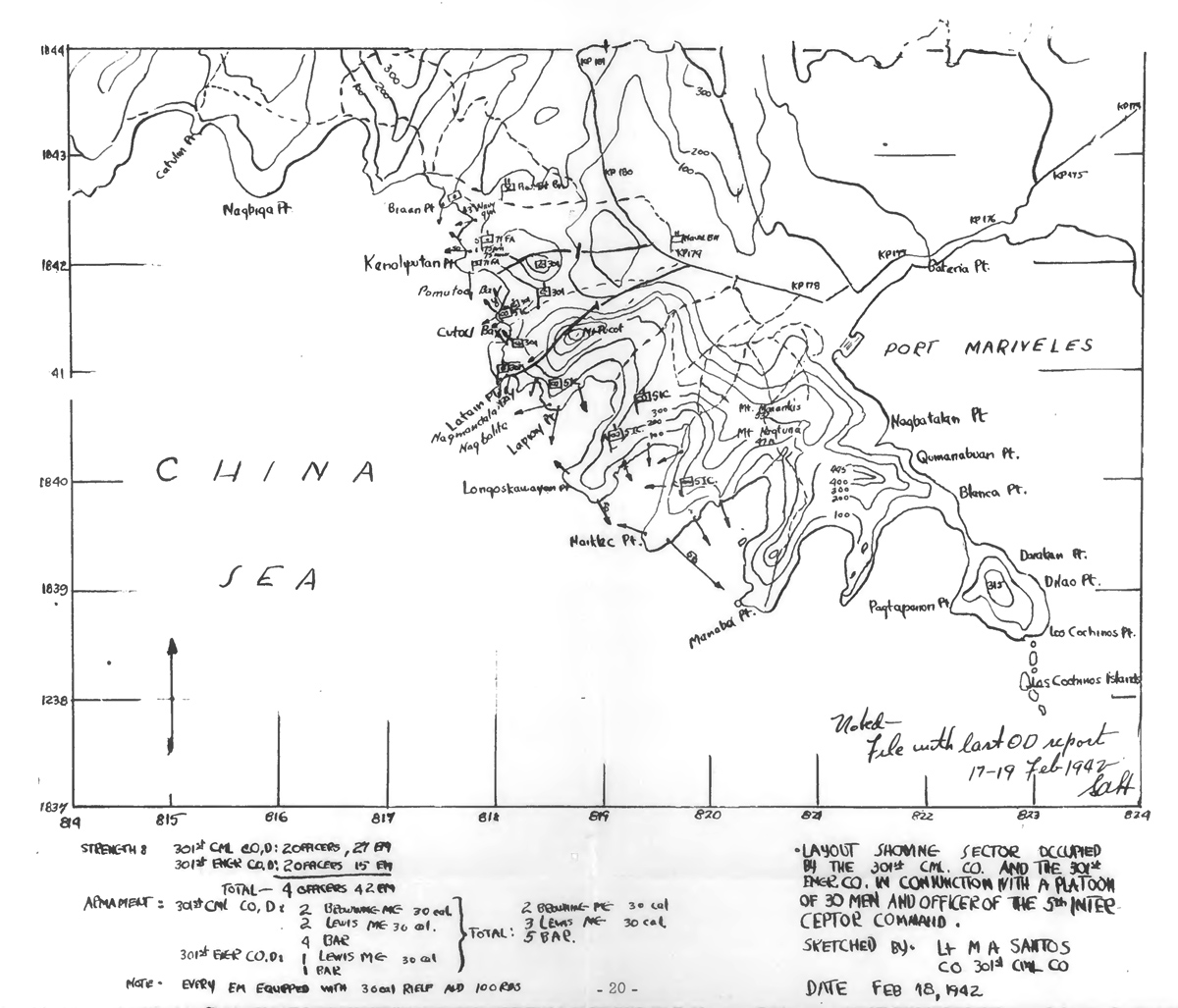

What followed came to be known as the Battle of the Points. One portion of the battle involved a Japanese amphibious force that had taken Lapiay Point and Longoskawayan Point, and also threatened Mount Pucot. On January 23, 1942, the Naval Battalion, an improvised unit of sailors acting as infantry under the command of U.S. Navy Captain Francis J. Bridget (1897–1945), engaged the Japanese.

Thanks to his background as an infantry officer, when the call went out for reinforcements, Roemer was well qualified to leap into action. He led a small group of Filipino soldiers into the battle, joining an ad hoc force of sailors, Marines, and Army Air Forces personnel. One document in Colonel Hamilton’s report described Roemer’s force as 60 men from the 301st Chemical Depot Company, while a map preserved in the report suggested it was 46 men, including 29 from the 301st Chemical Depot Company and 17 from the another Philippine Army unit, the 301st Engineer Depot Company.

Shortly after the war, Journal-Every Evening reported on a visit to Wilmington by Staff Sergeant Alfred F. Torrisi (1917–1956). A member of the 7th Chemical Company (Aviation) on detached service under Roemer’s command at the Fort McKinley and Bataan depots, Torrisi transferred to Corregidor on February 6, 1942. He recalled that Roemer had a good relationship with the Philippine Army soldiers under his command:

The rest of the troops under Colonel Roemer were Filipinos, “in whom he inspired a personal loyalty that few other American officers could obtain,” the sergeant said.

“Those Filipinos fought valiantly for four months just for Colonel Roemer, and he responded with an equal loyalty toward them,” the sergeant added.

With mortar and artillery support, including pack howitzers and heavy artillery from Fort Mills on Corregidor, the combined force drove the Japanese from Lapiay Point by January 26. The following day, reinforcements from the 57th Infantry (Philippine Scouts) arrived and went into action, killing or capturing the last of the Japanese in the area on January 31.

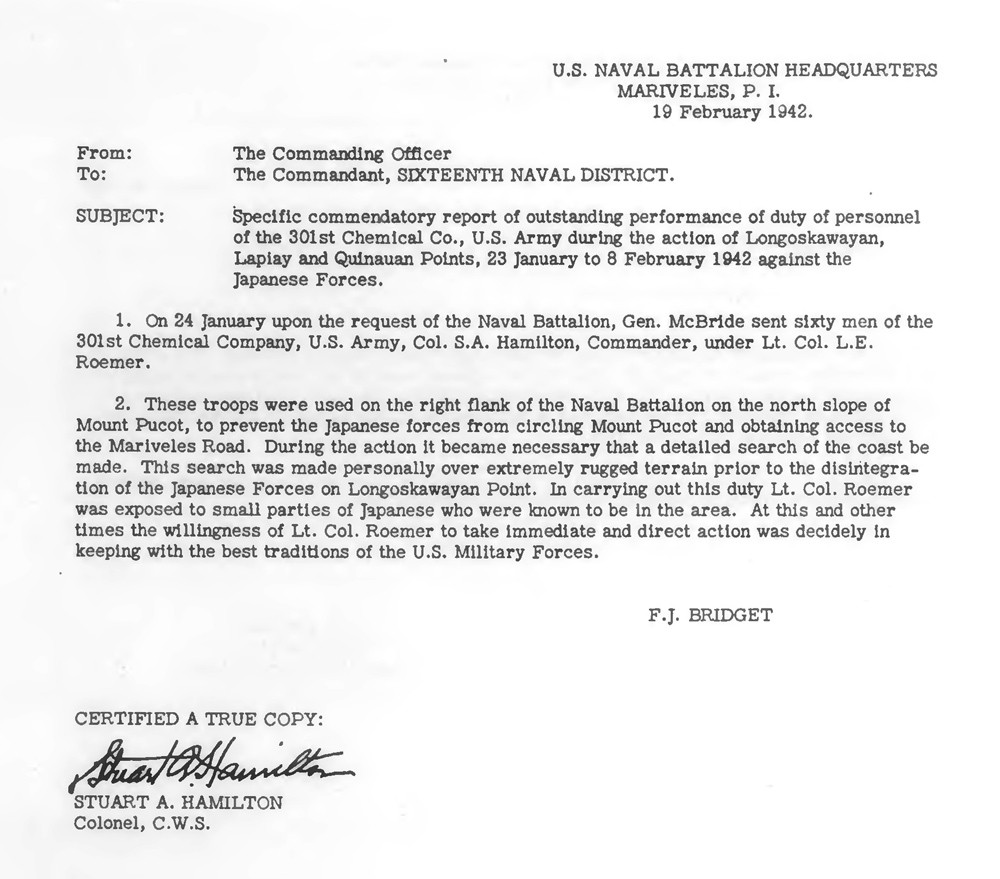

In a report dated February 19, 1942, Captain Bridget wrote of Roemer and his men:

These troops were used on the right flank of the Naval Battalion on the north slope of Mount Pucot, to prevent the Japanese forces from circling Mount Pucot and obtaining access to the Mariveles Road. During the action it became necessary that a detailed search of the coast be made. This search was made personally over extremely rugged terrain prior to the disintegration of the Japanese Forces on Longoskawayan Point. In carrying out this duty Lt. Col. Roemer was exposed to small parties of Japanese who were known to be in the area. At this and other times the willingness of Lt. Col. Roemer to take immediate and direct action was decidedly in keeping with the best traditions of the U.S. Military Forces.

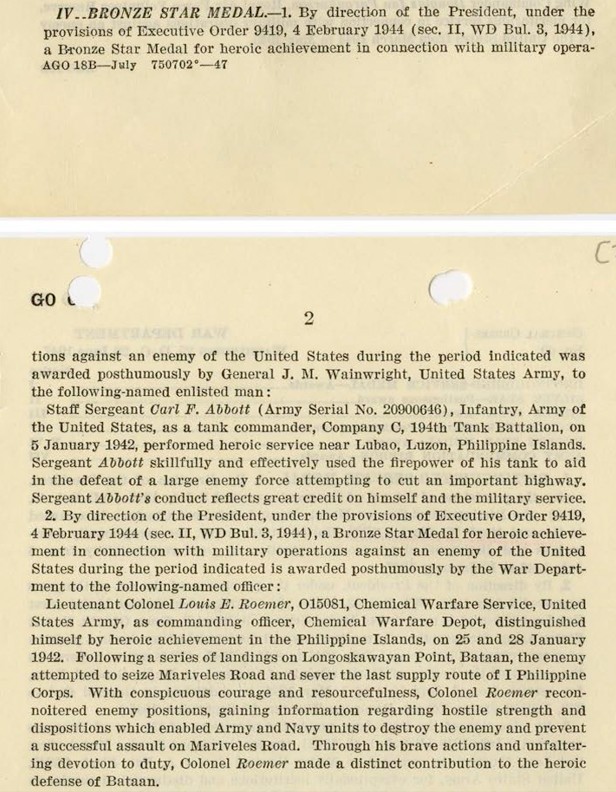

Roemer’s role in the Battle of the Points was also summarized in his posthumous Bronze Star Medal citation awarded per General Orders No. 60, War Department, dated June 28, 1947:

Lieutenant Colonel Louis E. Roemer, O15081, Chemical Warfare Service, United States Army, as commanding officer, Chemical Warfare Depot, distinguished himself by heroic achievement in the Philippine Islands, on 25 and 28 January, 1942. Following a series of landings on Longoskawayan Point, Bataan, the enemy attempted to seize Mariveles Road and sever the last supply route of I Philippine Corps. With conspicuous courage and resourcefulness, Colonel Roemer reconnoitered enemy positions, gaining information regarding hostile strength and dispositions which enabled Army and Navy units to destroy the enemy and prevent a successful assault on Mariveles Road. Through his brave actions and unfaltering devotion to duty, Colonel Roemer made a distinct contribution to the heroic defense of Bataan.

On March 9, 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Roemer, Colonel Hamilton, and Captain Louis T. Lazzarini (1912–1986) went on a mission to the front, inspecting I Philippine Corps units and discussing “CWS supply and training programs” at various command posts.

A reorganization on March 11, 1942, saw officers previously assigned to Headquarters Philippine Department reassigned to a new entity, Headquarters Luzon Force. Roemer remained assistant chemical officer. A journal entry made on Corregidor that day stated “Lt. Colonel Roemer arrived from Bataan this morning to inspect and plan the gas-proofing projects for Malinta Tunnel”—the headquarters bunker on Corregidor—“and Harbor Defense[s] of Manila and Subic Bays.” On March 12, after completing his plans and testing some Molotov cocktails, “Lt. Colonel Roemer returned to Bataan tonight by the 6:30 PM boat.”

In an April 1945 letter to Roemer’s wife that was quoted in Journal-Every Evening, Captain (then 1st Lieutenant) Frank L. Schaf, Jr. (1918–2002) wrote that Roemer “contracted a tropical disease during [the Battle of the Points] and it left him weak and sick.” Indeed, a document in Roemer’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) stated that he was under treatment at Little Baguio, Bataan, during February 18–21, 1942.

The last of the Japanese amphibious force on southern Bataan was defeated on February 13, 1942. Together with another setback for the Japanese in the Battle of the Pockets, the Battle of the Points caused the Japanese to briefly halt their offensive against Bataan.

Though the defenders exulted at their victory, events elsewhere in the Pacific had already sealed the fate of the Philippines. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was just the first of a series of disasters for the Allies that went on, practically unmitigated, for five months. Guam, Wake Island, and the Gilbert Islands fell in December 1941. Malaya fell in January 1942. Singapore capitulated in February 1942 and Dutch East Indies the following month. The American, British, Dutch, and Australian navies suffered devastating loses in a series of engagements, most notably the Battle of the Java Sea in February 1942. The Allies were not prepared to risk what assets they had left on a relief mission to the Philippines. With the Japanese in control of land, air, and sea for hundreds of miles around the islands, there would be no Dunkirk-like evacuation of the men on Bataan.

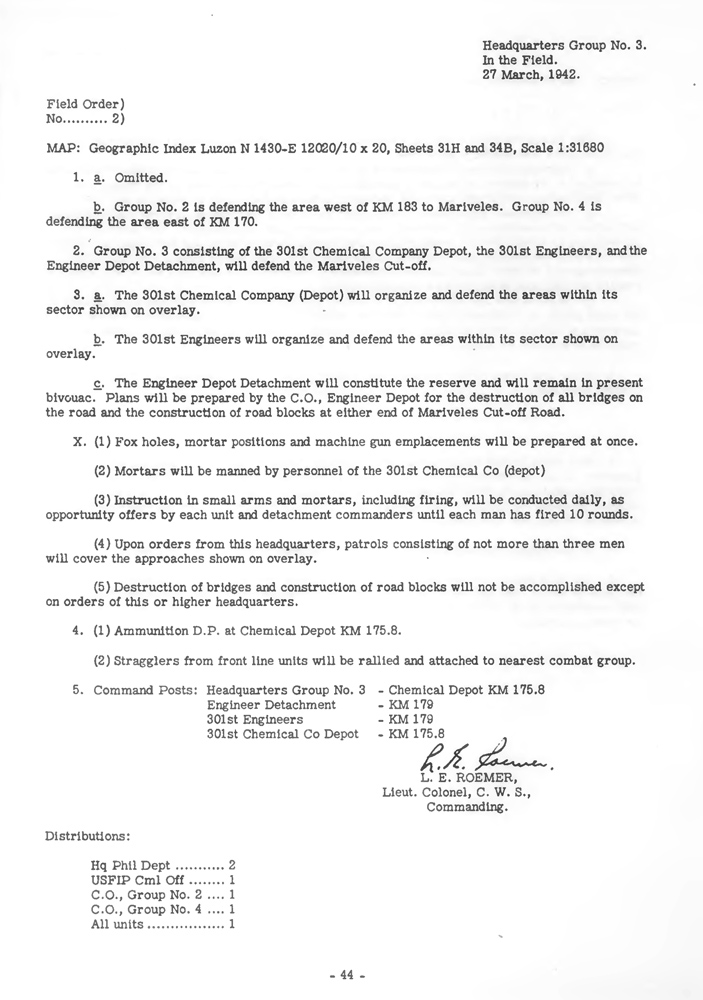

The Allied forces on Bataan grew weaker from hunger and disease as the Japanese grew stronger. By March 27, 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Roemer was in command of an ad hoc force known as Group No. 3, headquartered at the chemical depot on Bataan, and prepared to go into action as infantry once again. On that day, he issued orders that the group, “consisting of the 301st Chemical Company Depot, the 301st Engineers, and the Engineer Depot Detachment, will defend the Mariveles Cut-off.”

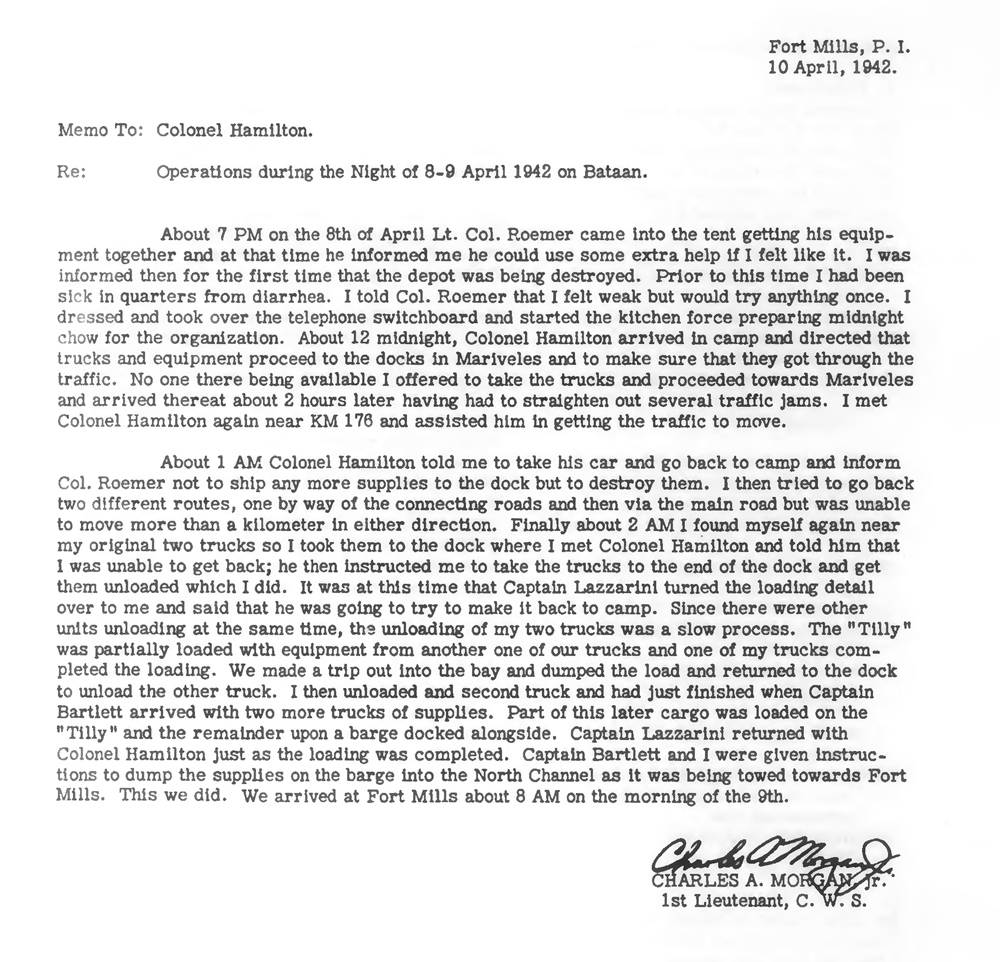

The renewed Japanese offensive proved unstoppable when it finally came. Captain Lazzarini later recalled in a statement dated April 10, 1942:

At approximately 10:00 A.M. on April 8, 1942 a communication was received from HPD [Headquarters Philippine Department] at the PCWD [Philippine Chemical Warfare Depot], stating that preparation and plans were to be made for the destruction of all material and supplies which would be of value to the enemy. […]

Upon receipt of the above mentioned communication, Col. S. A. Hamilton, Lt. Col. L. E. Roemer, and Capt. Lazzarini discussed ways and means of destroying all material and supplies then on hand in the PCWD on Bataan. It was finally concluded that the best method of destroying the supplies and assuring that none would fall into the hands of the enemy would be to dump as much of the chemical munitions as time would permit in the middle of Mariveles Bay and to destroy the rest of the munitions and depot stocks by fire.

1st Lieutenant Morgan recalled in a statement, also dated April 10, 1942:

About 7 PM on the 8th of April Lt. Col. Roemer came into the tent getting his equipment together and at that time he informed me he could use some extra help if I felt like it. I was informed then for the first time that the depot was being destroyed. Prior to this time I had been sick in quarters from diarrhea. I told Col. Roemer that I felt weak but would try anything once. […] About 12 midnight, Colonel Hamilton arrived in camp and directed that trucks and equipment proceed to the docks in Mariveles and to make sure they got through the traffic.

This proved easier said than done. It soon became clear that with traffic congestion on Bataan and limited shipping capacity it would be impossible to evacuate very much materiel to Corregidor. Morgan continued: “About 1 AM Colonel Hamilton told me to take his car and go back to camp and inform Col. Roemer not to ship any more supplies to the dock but to destroy them.”

Lieutenant Morgan was unable to get through to Roemer. C.W.S. officers dumped some white phosphorus munitions into the water while evacuating to Corregidor, but Lieutenant Colonel Roemer and several other officers were left behind. He and the rest of the Allied forces on Bataan surrendered later that day, April 9, 1942. Those men that escaped to Corregidor bought themselves less than one extra month of freedom, as the island fortress was captured on May 6, 1942.

Prisoner of the Japanese

The Japanese mistreatment of their American and Filipino prisoners was infamous. The defenders of Bataan endured a multiday forced march in the heat without adequate food or water, forever known to history as the Bataan Death March.

A remarkable number of extant accounts document how Lieutenant Colonel Roemer aided other Americans at the nadir of their miseries as prisoners of war. Schaf later stated of Roemer: “At the surrender of Bataan, he was able to get a box of much needed medical supplies and he used it on the men. He continued this work for the sick and wounded until his medical supplies ran out.” Schaf was on Corregidor at the time of the surrender and must have learned the story after his capture.

Journal-Every Evening reported information that Staff Sergeant Torrisi provided when he visited Wilmington after the war.

During the famed Death March, when dysentery was killing hundred every day, Colonel Roemer often slipped out of camp at night into the jungle to get wood for charcoal, from which he made the only soothing medicine available for the sick men, the sergeant recalled.

Like Schaf, Torrisi was captured on Corregidor and not present for the Bataan Death March, so he must have learned about it subsequently in a prisoner of war camp. If the details he obtained were correct and accurately reported by the newspaper, Lieutenant Colonel Roemer’s actions undoubtedly put him at extreme personal risk. During the march, Japanese guards injured or killed prisoners for most trivial offenses, or for no reason at all. Men who collapsed were frequently bayoneted or shot.

Roemer and the others who made it to San Fernando were crammed aboard freight cars and moved by rail to Capas before finally marching to Camp O’Donnell. Conditions there were abysmal. There was little water and inadequate sanitation facilities for the already weakened men. In a memoir written in 1945 but not published until 2016, David L. Hardee (1890–1969), a lieutenant colonel when captured on Bataan, recalled that when he first got to Camp O’Donnell:

Lieutenant Colonel Louis E. Roemer, an old friend who lived next door to us at Fort Howard, was there when we arrived. He helped me by giving me a sheet, some clothes, and other odds and ends. He said another day or two of marching would have done me much permanent injury.

Hardee also wrote about conditions there:

We had steamed rice three times a day and some salt. Usually it was accompanied with oleomargarine at breakfast and a vegetable and boiled camote soup for the other two meals. We had a little brown sugar occasionally but no meat and very little grease. […] The hospital had little or no medicine. There were not enough tools to dig enough latrines. Those that were dug were open ones, with no lumber for covering them. Flies were rampant. When you drew your food you ate with one hand and beat them off with the other. Everyone was weak and hungry. The starvation days in Bataan and the Death March had weakened all and would soon take its toll. […]

The men were weak, hungry, homesick, heartsick, and despondent. We were so numbed by the Death March that we could only eat and sleep. Despair, diarrhea, and dysentery seized them and the death rate began to mount.

In mid-1942, most of the prisoners at Camp O’Donnell were moved to another camp at Cabanatuan, in central Luzon. Conditions were better than at O’Donnell, but prisoners continued to die in large numbers.

1st Lieutenant Schaf, who was captured on Corregidor, recalled that he was reunited with Lieutenant Colonel Roemer at Cabanatuan in May 1942: “He was still sick. We were able to bring him back to health.”

In a letter to Roemer’s wife dated March 5, 1945, and quoted at length in Journal-Every Evening, Colonel Louis D. Hutson, who had served with Roemer in the 12th Infantry in the 1930s, recalled that although their paths did not cross on Bataan or for several years afterward—Hutson was at Bilibid Prison in Manila while Roemer was at Cabanatuan—that they were aware of one another’s presence in the Philippines:

In fact, he very kindly sent me, by one of the other officers, a small can of ham and eggs. This act I consider very unusual and showed the greatness of his heart, but knowing Louis from the old days it was not unexpected. As you know, food at that time was beyond price, and I greatly appreciated his thoughtfulness and kindness.

In contrast to Nazi Germany, the Empire of Japan did not make timely notifications to the U.S. government when they captured American prisoners of war. Wilmington newspapers reported that Roemer’s wife did not receive confirmation from the War Department that her husband was a prisoner of war until December 6, 1942, nearly one year into the Pacific War. Contact during the next few years was sporadic, with a handful of postcards sent from the Philippines reaching Roemer’s family months after they were written.

Conditions slowly improved at Cabanatuan. During Christmas 1942, the Japanese finally distributed packages from the Red Cross filled with food, medicine, and hygiene supplies. John C. McManus wrote in his book, Fire and Fortitude: The US Army in the Pacific War, 1941–1943, that during late 1942 and 1943:

Food consumption rose from starvation to subsistence levels. Death and disease rates declined. The average prisoner received between two thousand and twenty-six hundred calories per day. […] Meals consisted mainly of steamed rice, beans, scrawny sweet potatoes, or onions or squash, augmented with a little carabao meat, maybe an ear of corn or a tomato.

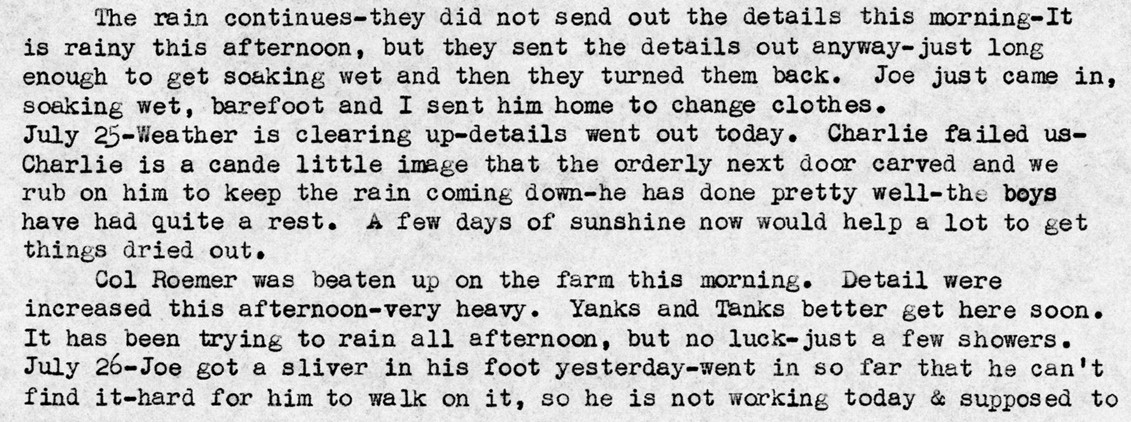

Sanitation also improved and a septic system replaced open latrines. Some prisoners earned extra food and a small amount of money, which they could spend in the camp’s commissary, by working on the camp’s farm. The Japanese allowed the prisoners to entertain themselves with plays, concerts, lectures, and sports. There was even a camp library. Still, many guards were quick to resort to violence for minor or imagined infractions, and attempting to escape was punishable by death. Major Elbridge Reed Fendall (1916–c. 1944) of the 57th Infantry (Philippine Scouts), who kept a secret diary in the camp, noted in an entry from July 25, 1943: “Col Roemer was beaten up on the farm this morning.”

Frank L. Schaf, Jr. recalled in his letter that he had been separated from Colonel Roemer from October 1942 when Schaf was transferred to another camp at Davao, but they were reunited at Cabanatuan in June 1944:

He was in good health. He had been using everything he could get his hands on for the enlisted men. He was at that time in charge of a detail that was building an airport for the Japanese near the camp.

As the war turned against the Japanese, conditions in the prison camps began to deteriorate again. Hope rose when American troops began landing in the southern Philippines in mid-October 1944. Unfortunately, the Japanese began to evacuate their prisoners from Luzon just as their liberation appeared imminent.

In the final entry in his diary, dated October 11, 1944, Major Fendall wrote that he learned that he would be in a “detail of 475 officers”—possibly also including Lieutenant Colonel Roemer—leaving Cabanatuan the following day. He wrote:

We have spent nearly entire afternoon [eating] bread, fried vegetables & camotes. Will probably be sick. Trouble is we can’t take much with us and must try to eat it all. […]

Am going to bury this and hope somebody gets it who doesn’t have to leave. Must just now [go] and pack. May God be with us.

Love to mother and Bob, family & friends if I don’t make it. Hope the Japanese get what they deserve before this war is over with.

Captain Schaf later wrote of Colonel Roemer: “In October of 1944 he was sent to Bilibid Prison in Manila, to await shipment to Japan. The detail left Bilibid on Dec. 13, 1944. That was the last time that I saw him.” He closed his letter to Roemer’s wife: “Colonel Roemer installed such love in his men and we respected him so much, that it would be only a pleasure if I could do anything more for you.”

In his March 5, 1945, letter to Roemer’s wife, written one month after his own liberation from captivity, Colonel Hutson recalled:

On about Dec. 1 of last year, Louis, with many other officers, was brought through Bilibid on his way to Japan. He spent several weeks in Bilibid Prison where I was, and I had the pleasure of renewing our old friendship of Fort Howard days. He was transferred out for Japan or Formosa, but I feel certain that Louis was one of those who successfully made the trip.

Colonel Hutson was quoted in another Journal-Every Evening article—it is unclear if it was the same letter—as writing about Roemer:

At the time of his transfer he was in very good health and quite cheerful and he asked that in case I were returned to the States before he returned that I write you and send you and his boys and his mother all his love.

On December 13, 1944, Colonel Roemer and over 1,600 other Allied prisoners were crammed aboard Oryoku Maru. The ship was overloaded with both Allied prisoners and Japanese civilians. For the prisoners in the holds, the heat was unbearable. There was inadequate food and water. Sanitation, space, and ventilation were non-existent. The hell ship got underway that evening. Dozens of men died from the abysmal conditions even before U.S. Navy aircraft bombed and strafed the ship on the morning of December 14, 1944. Some Americans were killed outright in the attack, but the survivors’ ordeal was only beginning.

Oryoku Maru staggered back to Subic Bay. The Japanese began evacuating the ship’s passengers, while ordering the Americans to stay put aboard the foundering ship. Men who tried to escape the ship were ruthlessly shot. Finally, the next day, December 15, 1944, the prisoners were allowed to abandon ship, though only some of the wounded were allowed to use lifeboats. The other weary men had to swim for their lives. Another American air raid struck the ship, killing more prisoners. Even after everything else, the Japanese machine gunned some of the survivors as they struggled to shore. The ship finally sank that same day.

Lieutenant Colonel Roemer survived the sinking of the Oryoku Maru. He was placed aboard another hell ship, most likely Enoura Maru but possibly Brazil Maru, both of which sailed from San Fernando on December 27, 1944. It was just under two weeks before American forces began landing on Luzon. Conditions, once again, were abysmal. The ships reached Takao, Formosa (Kaohsiung, Taiwan), on January 1, 1945. There, the prisoners from Brazil Maru were packed in with the others aboard Enoura Maru.

On January 9, 1945, American naval aircraft attacked Formosa in support of the landings at Lingayen Gulf on Luzon. They found Takao’s harbor full of ships. Multiple bombs struck Enoura Maru, killing hundreds of American prisoners.

Lieutenant Colonel Roemer most likely died aboard Enoura Maru, possibly in the attack, and was buried at Takao. The remaining American prisoners, which according to erroneous Japanese records included Roemer, eventually shipped out aboard Brazil Maru for the Japanese Home Islands. Many hundreds more prisoners died during that journey.

Of the over 1,600 Allied prisoners who had boarded Oryoku Maru in December 1944, about 1,100 are believed to have died during the subsequent voyages aboard the three hell ships, and about 100 more once they reached Japan. The victims included Lieutenant Colonel Roemer, Captain Bridget, Major Fendall, and several Delawareans: Master Sergeant Andrew Gorman (1896–1944), 1st Lieutenant William H. Marvel (1915–1944), and Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Joseph W. Stirni (1908–1945).

Japanese recordkeeping, like its treatment of its prisoners, was very poor. A list of prisoner fatalities aboard Enoura Maru did not include Lieutenant Colonel Roemer’s name. The Japanese finally submitted a report through the International Red Cross that he died at sea of acute colitis on January 22, 1945, and that his remains were cremated. War crimes trials also revealed that some victims who died aboard hell ships were thrown overboard by the Japanese.

Journal-Every Evening reported:

Sergeant Torrisi told Mrs. Roemer he was not with Colonel Roemer when he died. However, he said he learned from others that the colonel received an arm wound from shrapnel dropped by an American plane as his group was about to embark on a Japanese transport to leave the Philippines.

The colonel died several days later when the ship had reached Formosa, according to the story the sergeant obtained.

Assuming that the story was accurate, it is unclear if the attack that wounded Roemer indeed occurred in Manila prior to boarding Oryoku Maru, or was conflated with the later strikes on Oryoku Maru and Enoura Maru. The second part, that Roemer had died at Formosa, is supported by the fact that his body was indeed buried there, though confirmation would not come for decades afterward.

Based on what Sergeant Torrisi had learned, he expressed bewilderment at the official notification that Roemer died of colitis on January 22, 1945. It does not reflect well on American authorities that Staff Sergeant Torrisi, who survived an earlier hell ship journey aboard Tottori Maru in 1942 and survived the war in a camp in Japan, was able to obtain a more accurate account of Roemer’s demise from other prisoners than government investigators. If there was any systematic effort by American authorities to interview survivors to determine the fates of those lost aboard hell ships with any more accuracy than Japanese records—known to be of dubious accuracy even at the time—that documentation was not available to the board of officers who deemed Roemer non-recoverable in 1947.

Journal-Every Evening reported that Roemer’s stepson, Captain Ralph S. Learn of the Army Air Forces, had volunteer to fly a relief mission transporting supplies from Tinian to a prison camp in Korea via B-29 Superfortress shortly after the Japanese capitulated in 1945. At that time, he knew Roemer had been a prisoner but was unaware of his fate.

The bitter news of Roemer’s death reached his wife and son in Three Arch Bay, Laguna Beach, California, shortly before the Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed in Tokyo Bay.

At a ceremony in Red Bank, New Jersey, on August 29, 1947, Captain Henry J. Boudreaux presented Mary Roemer with the Legion of Merit and Bronze Star that her husband had earned. She eventually remarried to William Lewis Lyon (1896–1968) in Washington, D.C, in May 1956.

Decades passed before the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing in Action Accounting Agency revealed on January 14, 2026, that Lieutenant Colonel Roemer’s remains had been identified:

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Command was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel. In May 1946, AGRC Search and Recovery Team #9 exhumed a mass grave on a beach at Takao, Formosa, recovering 311 bodies. Following unsuccessful attempts to identify the remains, they were declared unidentifiable. They were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

Between October 2022 and July 2023, DPAA disinterred Unknowns from the Punchbowl linked to the Enoura Maru. The remains were accessioned into the DPAA Laboratory for further analysis.

To identify Roemer’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial, Y-chromosome and autosomal DNA analysis.

The exact date and cause of Roemer’s death remain unknown. It is likely that he died in the American air raid on January 9, 1945, but as the press release observed, “he conceivably could have died at any point during this December 1944 to January 1945 POW transport, including the Jan. 9 attack on the Enoura Maru.”

Lieutenant Colonel Roemer’s name is honored on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines, on the University of Delaware’s World War II memorial, and on the Wall of Remembrance at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware. Soon, his remains will be reburied for the final time in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where his widow’s body rests.

Notes

Party Location

The 1929 party that led to Roemer’s brief marriage was reported in the press as “Ridgewood, S. C.” There is no such town in South Carolina, but Ridgeland is the county seat of Jasper County, where the marriage took place.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Matt LeMasters for obtaining Edgewood Arsenal rosters from 1940 and to War Department Archives for digitizing the portrait of Roemer and photos from the C.W.S. report.

Bibliography

“3 U. of D. Graduates Are Made Army Majors.” Journal-Every Evening, July 22, 1940. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189044565/

“Alfred F Torrisi.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53165683/alfred-f-torrisi

“Army Orders.” Army and Navy Journal, June 24, 1939. https://archive.org/details/sim_armed-forces-journal_1939-06-24_76_43/mode/2up

“Army Orders.” Army and Navy Journal, September 13, 1941. https://archive.org/details/sim_armed-forces-journal_1941-08-13_79_2/page/38/mode/2up

“Army Orders.” San Francisco Chronicle, June 21, 1939. https://www.newspapers.com/article/190113399/

The Blue Hen 1920-1921. Courtesy of the University of Delaware. https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/e2826c64-e0a9-40ed-97c7-f234eef5d080/content

Brophy, Leo P. and Fisher, George J. B. The Chemical Warfare Service: Organizing for War. Originally published in 1959, republished by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1989. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/10-1.pdf

Brophy, Leo P., Miles, Wyndham D., and Cochrane, Rexmond C. The Chemical Warfare Service: From Laboratory to Field. Originally published in 1959, republished by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1988. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/10-2.pdf

“Captive’s Family Puzzled by Card.” Journal-Every Evening, August 31, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189390353/

Census Record for Lewis [sic] E. Roemer. April 15, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9M1-CXTK

Census Record for Louis E. Roemer. April 21, 1910. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRND-FJP

Census Record for Louis E. Roemer. April 25, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR4P-HRQ

Census Record for Louis E. Roemer. January 3, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9R6C-82Z

Certificate of Birth for Lewis [sic] E. Roemer. Undated c. March 1901. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-XC83-QDY

“City Army Colonel Removed From Philippines by Japs.” Journal-Every Evening, March 30, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189386919/

“City Officer Saved Hundreds, Only to Die as Freedom Neared.” Journal-Every Evening, November 24, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/190222092/

“The Civilian Conservation Corps Part II: A Maryland Perspective.” Maryland Department of Natural Resources website. https://dnr.maryland.gov/centennial/Pages/Centennial-Notes/CCC_History_Part_II.aspx

Civilian Conservation Corps Record for Morris L. Weinberg. Individual Records (Enrollees), 1933–1943. Record Group 146, Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, 1871–2001. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-146/12034477/12034477-12518/12034477-12518-07.pdf

Clay, Steven E. U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919–1941, Volume 1. The Arms: Major Commands and Infantry Organizations, 1919–41. Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16040coll3/id/198/rec/3

Clay, Steven E. U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919–1941, Volume 4. The Services: Quartermaster, Medical, Military Police, Signal Corps, Chemical Warfare, and Miscellaneous Organizations, 1919–41. Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16040coll3/id/200/rec/1

Coffman, Edward M. The Regulars: The American Army, 1898-1941. Belknap Press, 2004.

“Consolidated Monthly Roster Camp Knox Kentucky.” April 30, 1923. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-F9KF-5

“Dazed, Happy Jobless Reach Forest Camp.” The Sun, May 23, 1933. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189387790/

Dickson, Paul, and Allen, Thomas B. The Bonus Army: An American Epic. Originally published in 2004, republished by Dover Publications, 2020.

“Doris K. Ferguson Bride Of Albert H. Tomlinson.” The Morning Call, December 24, 1934. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189397446/

“Enoura Maru Identification Project.” Undated, c. 2025. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. https://dpaa-mil.sites.crmforce.mil/Projects/WWII/EnouraMaru/InfoSheet

“Ex-Delaware Students to be Army Officers.” Wilmington Morning News, January 27, 1923. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189045001/

Fendall, Elbridge R. “Diary of Major E.R. Fendall, 57th Infantry (PS).” Diaries and Historical Narratives, 1940–1945. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/opastorage/live/43/4418/12441843/content/arcmedia/dc-metro/rg-407/Entry-1067/Box_129/Folder14/1255524_Box129_Folder14.pdf

“Flier Is Home; Bombed Japan.” Journal-Every Evening, November 8, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189390640/

“Florida Deaths.” The Tampa Tribune, April 4, 1969. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189393847/

“Francis J. Bridget, Capt, USN.” U.S. Naval Academy Virtual Memorial Hall. https://usnamemorialhall.org/index.php/FRANCIS_J._BRIDGET,_CAPT,_USN

“Gen. Gibbs Hands Diplomas to 242.” Asbury Park Evening Press, June 15, 1931. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189400523/

“General Orders No. 60, War Department.” June 28, 1947. Official Military Personnel File for Mark W. Clark. Official Military Personnel Files, 1912–1998. Record Group 319, Records of the Army Staff. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-319/299741/Clark_Mark_W_1.pdf

“Give Banquet to Company B.” The Evening Journal, June 1, 1922. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189388449/

Gladwin, Lee A. “American POWs on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell.” Prologue Magazine, Winter 2003. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2003/winter/hell-ships

Hamilton, Stuart A. “Activities Chemical Warfare Service, Philippine Islands, World War II.” November 22, 1946. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/dc-metro/rg-407/305275/305275-Microfilm-NDL/WW2-OR-30-10/WW2-OR-30-10.pdf

Hardee, David L. Bataan Survivor: A POW’s Account of Japanese Captivity in World War II. University of Missouri Press, 2016.

Hudson, Robert Logan. “Draft Rosters of Army POW’s [sic] Showing Transfers From Bilibid Prison to Other Camps in 1944 or Earlier.” The West Point Connection website. https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/HudsonFast/BilibidDbf.htm

Hurst, Michael. “The Story of the Bombing of the Enoura Maru.” Never Forgotten: The Story of the Taiwan POW Camps and the men who were interned in them. http://www.powtaiwan.org/archives_detail.php?The-Story-of-the-Bombing-of-the-Enoura-Maru-17

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Louis E. Roemer. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Kleber, Brooks E. and Birdsell, Dale. The Chemical Warfare Service: Chemicals in Combat. Originally published in 1966, republished by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1990. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-D114-PURL-gpo94184/pdf/GOVPUB-D114-PURL-gpo94184.pdf

“L. E. Roemer’s Death Revealed By Red Cross.” Journal-Every Evening, September 1, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189011378/

“Lenroot Predicts Disaster Unless Laws Are Upheld.” Wilmington Morning News, June 13, 1922. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189044886/

“Lieut. Col. Roemer Prisoner of Japs, Wife is Informed.” Wilmington Morning News, December 7, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/190112724/

“Local Officer Jap Prisoner.” Journal-Every Evening, December 7, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189387187/

“Maj Elbridge Reed Fendall.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56788027/elbridge-reed-fendall

“Marriage License Applications. The Evening Star, May 5, 1956. https://www.newspapers.com/article/190127718/

“Marriage License for Louis Edward Roemer and Doris Katherine Ferguson.” August 17, 1929. South Carolina County Marriage Licenses, 1911–1953. South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, South Carolina. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C91V-63XZ-C

McManus, John C. Fire and Fortitude: The US Army in the Pacific War, 1941–1943. Dutton Caliber, 2019.

Miley, Jack. “Vacation Lark Doesn’t Sing to Unwilling Bride.” Daily News, January 11, 1931. https://www.newspapers.com/article/189044701/

“Miss Helen L. Roemer.” Journal-Every Evening, March 28, 1955. https://www.newspapers.com/article/190122117/

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry Fort Howard, Maryland.” June 30, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-XSC6-B

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Maryland.” August 31, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-FN1

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Maryland.” June 30, 1932. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-FSLV

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Maryland.” April 30, 1932. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-XSZV-N

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Maryland.” March 31, 1932. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-F7F5

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Maryland.” March 31, 1933. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-FQVK

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Md.” April 30, 1933. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-XS3Y-M

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Md.” August 31, 1932. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-FQLS

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry Ft. Howard, Md.” December 31, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-FWMP

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Md.” December 31, 1932. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-F31R

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Md.” December 31, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-FGF

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry Ft. Howard, Md.” February 29, 1932. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-F321

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry Ft. Howard, Maryland.” January 31, 1932. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-FQX1

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Md.” January 31, 1933. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-F3YQ

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Md.” July 31, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-F7HQ

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Fort Howard, Md.” May 31, 1933. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-XSQW-9

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Ft. Howard, Md.” November 30, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-F9C8

“Monthly Roster 12th Infantry, Ft. Hoyle, Maryland.” September 30, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3CP-F9V6

“Monthly Roster Camp Knox, Kentucky.” May 31, 1923. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3CP-F9TM-1

“Monthly Roster Chemical Warfare School Edgewood Arsenal, Md.” December 31, 1939. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V367-4TQ5

“Monthly Roster Co. D, 8th Infantry Fort Screven, Georgia.” June 30, 1929. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-P3GP-F

“Monthly Roster Co. M, 45th Infantry (PS), Ft Wm McKinley, P.I.” April 30, 1926. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3H5-3QSL-L

“Monthly Roster Co. M, 45th Infantry (PS), Ft. Wm. McKinley, P.I.” February 28, 1926. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3H5-3Q7D-W

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ Eighth Infantry Fort Screven[,] Georgia.” June 30, 1929. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-P3WT-3

“Monthly Roster Company D, 8th Inf. Fort Screven, Ga.” September 30, 1928. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HF-P3KH-2