| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Grocery store manager for the American Store Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32959416 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “A,” 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 745 (rifleman) | Normandy |

| Awards | Entered the Service From |

| Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge | Wilmington, Delaware |

Early Life & Family

John Joseph Bukowski was born in Wilmington, Delaware, likely on October 21, 1912. He was the sixth child of Aleksander (Alexander) Bukowski (c. 1881–1956) and Stanislawa (Stella) Bukowski (née Romanowska, c. 1886–1971), Polish immigrants from what was then the Russian Empire. His father was a Morocco leather worker. Bukowski had three older sisters, two older brothers, a younger sister, and three younger brothers (one of whom died very young). He was Catholic.

Bukowski’s parents purchased a home at 908 Linden Street on October 24, 1912. The family was recorded living at that address at the time of the 1920 census. On March 25, 1924, Bukowski’s parents purchased a home at 1302 Lancaster Avenue. It appears that he lived at that address until he married.

Bukowski completed two years of high school before dropping out in 1929. That same year, he began working as a salesclerk for a grocery store chain, the American Store Company. In 1931, he completed two years of bookkeeping school at Goldey College in Wilmington.

Bukowski married Jeanette Josephine Makowska (a seamstress, c. 1913–1991) in Wilmington on the afternoon of February 7, 1937. Around 1939, he was promoted to store manager, supervising between four and 12 salesclerks. When he registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, Bukowski was living with his wife at 207 South Adams Street and working at the American Store at the corner of Lancaster Avenue and Jackson Street.

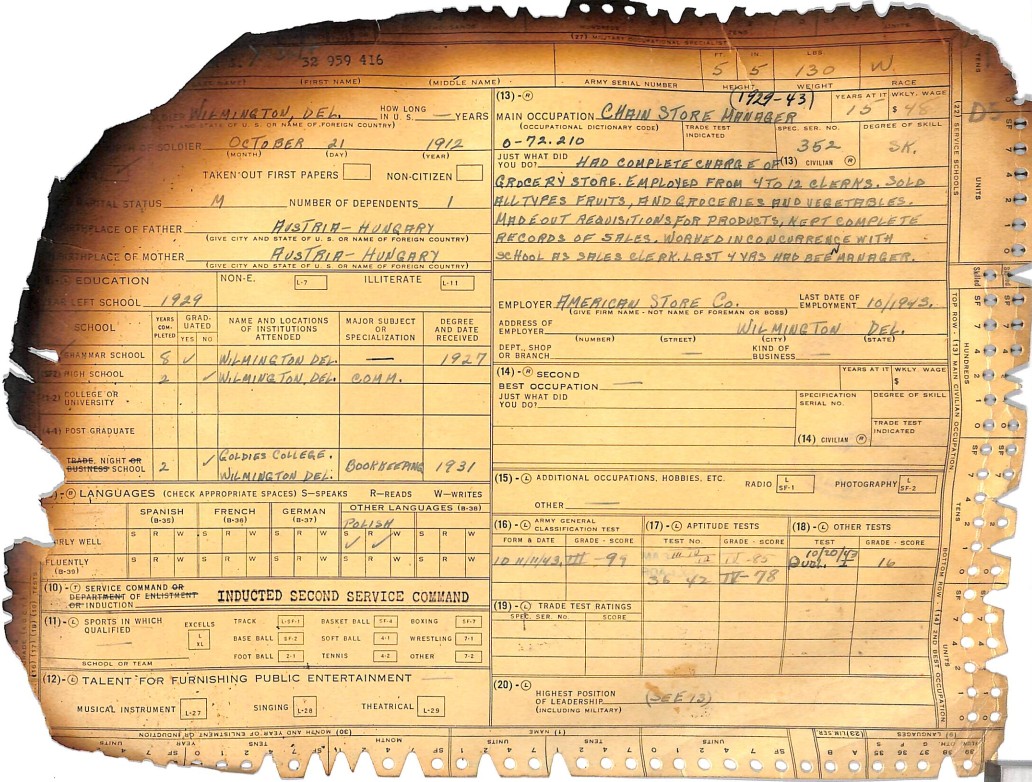

Private Bukowski’s U.S. Army personnel file survived the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire largely intact. As of June 23, 1941, when he filled out an affidavit following his registration for Selective Service, Bukowski was earning $32 per week (about $707 in 2025 dollars). He was earning $48 per week by the time he entered the service (about $896 in 2025 dollars).

In September 1943, Bukowski was assessed by Local Board No. 3, Wilmington, to determine whether he was suitable for military service. The board classified him as eligible for service on September 10, 1943.

Military Training

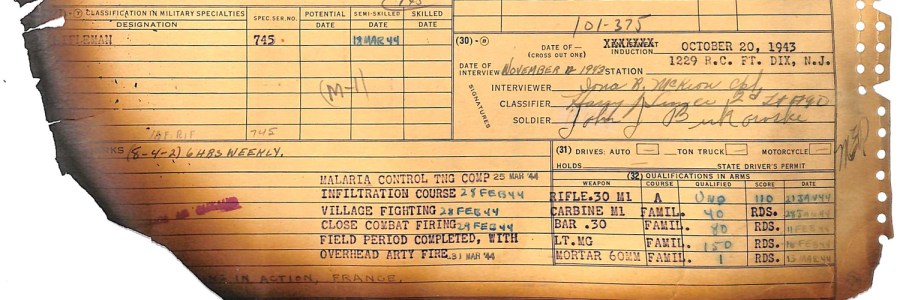

After he was drafted, Private Bukowski was inducted into the U.S. Army at Camden, New Jersey, on October 20, 1943. At the time, he stood five feet, five inches tall and weighed 130 lbs., with brown hair and blue eyes. His medical examination noted that he had uncorrected myopic astigmatism with 20/50 vision in each eye and full dentures.

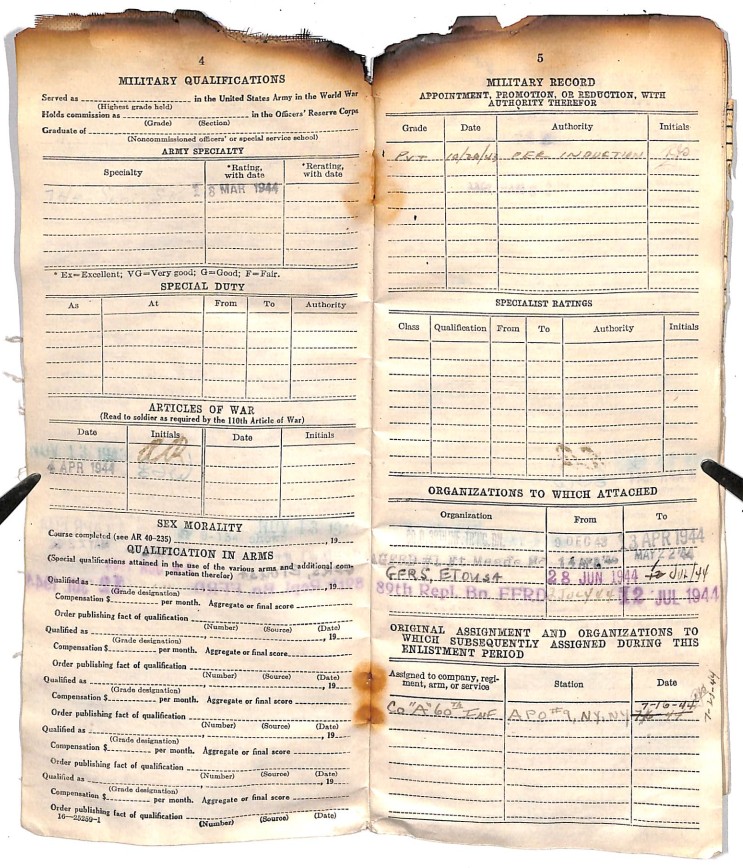

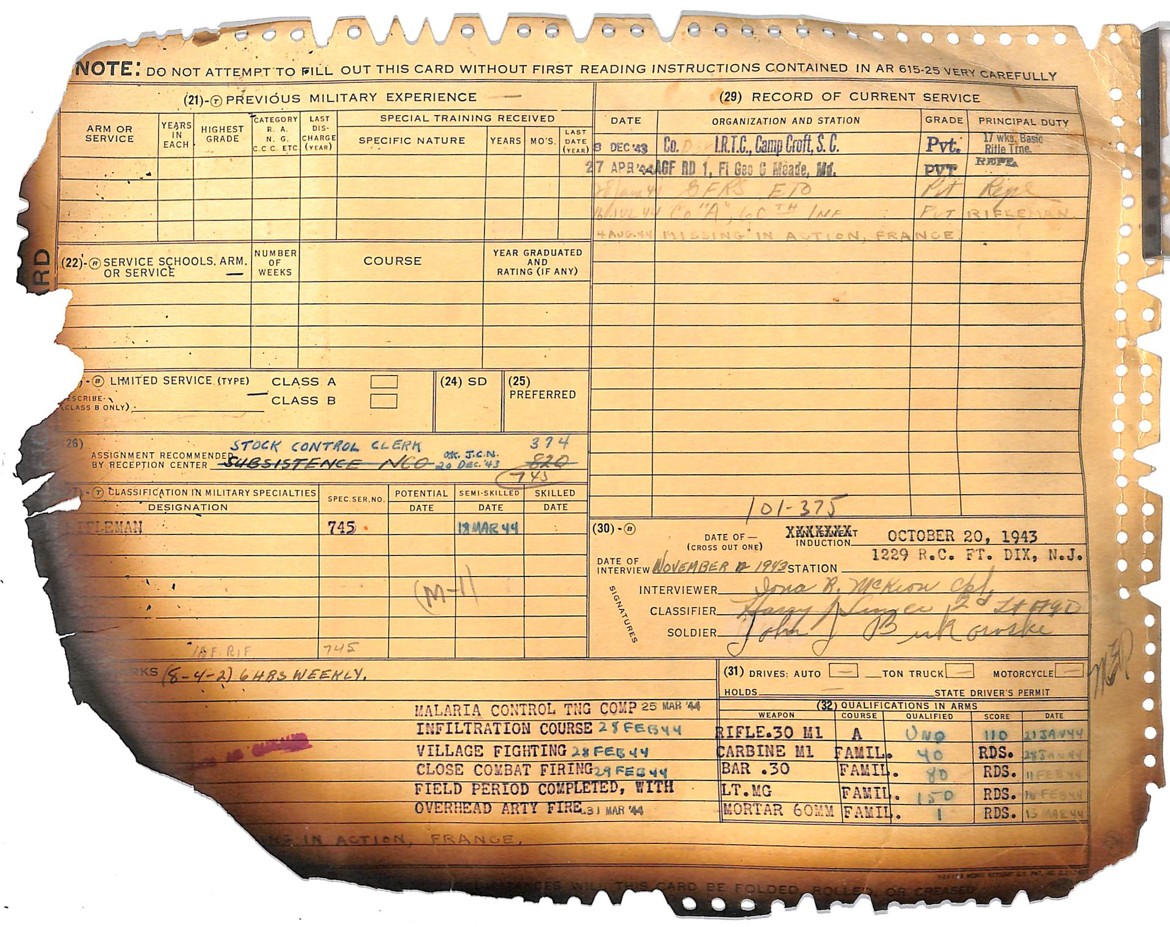

Bukowski was briefly placed on inactive duty to conclude matters pertaining to his civilian life. He went on active duty on November 11, 1943, and was attached unassigned to the 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey. That same day, he took the Army General Classification Test. His score of 99 placed him in Class III, an average rating on the five-class scale. The following day, he sat for a classification interview.

Based on his work history, the classifier suggested that Bukowski would be qualified for the military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code 820, subsistence noncommissioned officer. This was subsequently changed to 374, stock control clerk. By late 1943, however, the U.S. Army had plenty of stock control clerks. With combat ramping up in both Europe and Asia and casualties mounting, it needed riflemen above all else.

Curiously, a document in his personnel file suggests that he was transferred to the 31st Coast Artillery Regiment in Key West, Florida, on November 27, 1943. This transfer must have been cancelled, since there was no report date with that unit and as of December 7, 1943, Bukowski was still at Fort Dix. On that day, he was dispatched to the Infantry Replacement Training Center, Camp Croft, South Carolina.

On December 8, 1943, Private Bukowski was attached unassigned to Company “D,” 38th Infantry Training Battalion, Infantry Replacement Training Center, Camp Croft, South Carolina, an assignment confirmed the following day. Bukowski fired the M1 Garand rifle on the range on January 21, 1944. His Course “A” score of 110 was not high enough to qualify, but during World War II qualifying with a weapon was not a prerequisite to serve as either a U.S. Army or Marine Corps rifleman.

Bukowski also fired an M1 carbine, a Browning Automatic Rifle, a light machine, and a 60 mm mortar for familiarization purposes. His training included also included satisfactory participation in infiltration, close combat, and urban combat courses, as well as experiencing artillery shells fired overhead. After completing basic training, on March 18, 1944, he was designated as a rifleman, M.O.S. code 745.

On April 13, 1944, Private Bukowski was detached from his training unit and began a furlough. At the end of his visit home, on April 27, 1944, he reported to Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot No. 1, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland. He was detached on May 22, 1944, and assigned to Shipment GV-150(a)-A.

Bukowski shipped out from the New York Port of Embarkation on June 16, 1944, arriving eight days later in the United Kingdom.

It is unlikely that Bukowski ever learned that his younger brother, Private 1st Class Henry J. Bukowski (1923–1984), a rifleman in Company “E,” 115th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, had survived Omaha Beach on D-Day in Normandy only to be taken prisoner a few days later.

Combat in Normandy

On June 28, 1944, Private Bukowski entered the Ground Forces Replacement System and was attached unassigned to the 12th Replacement Depot. The replacement depots—repple depples in solder slang—were not well liked by the troops. In his book, Beyond the Beachhead, historian Joseph Balkoski explained:

Replacements were the army’s homeless. After a hasty separation from the units with which they had trained or fought, the lonely replacements found themselves in an unfamiliar repple depple, where they lost all sense of belonging to a cohesive military unit. Even new friendships made within the replacement depots were generally fleeting since it was unlikely that two buddies would be assigned to the same squad, or even the same platoon. Many replacements thought of themselves as nameless pieces of army equipment, like crates of ammunition, sent to the front and promptly consumed. […] “Being a replacement is just like being an orphan,” a rifleman recalled.

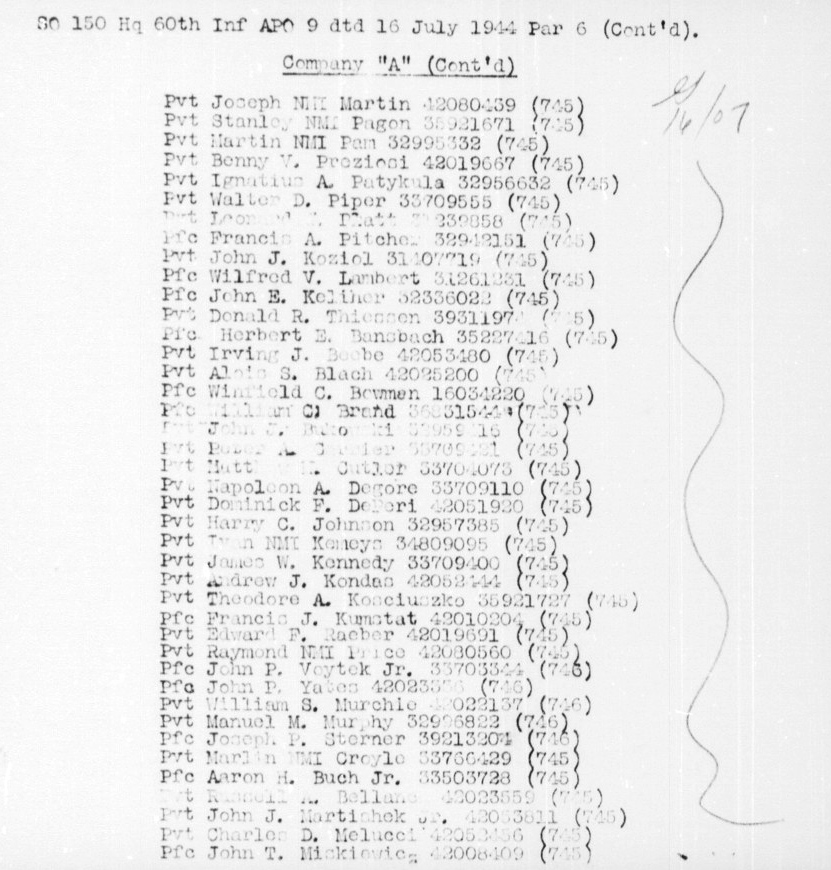

Bukowski was attached unassigned to the 89th Replacement Battalion during July 2–12, 1944, before shipping out for France. After arriving in France on or about July 15, 1944, he was briefly attached to the 92nd Replacement Battalion before he was transferred to the 9th Infantry Division. On July 16, 1944, he joined Company “A,” 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division.

If a replacement was lucky, he joined his new unit when it was out of the line or at least in a quiet sector. Having a few days to acclimate to the combat area and to get to know his new squadmates could mean the difference between life and death. A lucky replacement might find himself under the wing of one or more veteran soldiers who could impart the wisdom that combat experience had provided them. An unlucky one would find himself deposited at the front in the middle of a battle, sometimes with squadmates who were indifferent to the fate of the raw new rifleman replacing one of their buddies. The veterans might warm to a replacement once he proved himself, if he was not cut down before he got that chance.

Private Bukowski was not lucky. When he joined the 60th Infantry, his regiment was in the middle of intense combat northwest of Saint-Lô during the Battle of Normandy. The 60th Infantry’s overall advance was south toward the road connecting Périers and Saint-Lô, a move fiercely contested by the Germans, including elite paratroopers. As of July 15, 1944, the day before Bukowski joined, “1st Battalion was echeloned to the left rear”—in this case, to the northeast of—of 2nd Battalion, which was “making the main effort in the center.” That afternoon, Company “C” prepared to move against the enemy’s flank, but did not do so that day.

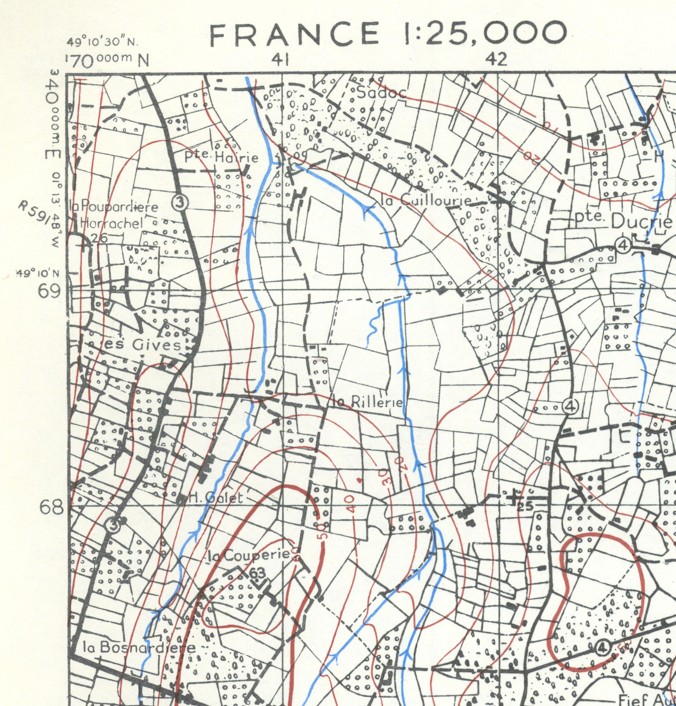

When Bukowski joined Company “A,” 1st Battalion was on the left of the regiment near L’Oliverie. Nearby Sadoc (49° 10’ 28” North, 1° 12’ 39” West) was still occupied by the enemy. Located northwest of La Petite Ducrie and near a farm, La Rivière, Sadoc was surrounded by at least one orchard as well as farmers’ fields separated by the hedgerows typical of Normandy. Little more than a point on a map—it risks exaggeration to even describe it as a hamlet—Sadoc had been in decline since even before the outbreak of World War I. La Rivière is still there, but there is nothing left of Sadoc today.

To the south, on the other side of an unpaved road, was Bois des Landes, a small wooded area. Its size belied its strength as defensive position. Although not particularly deep, Bois des Landes was nearly a mile wide. Its German defenders were dug in and had clear fields of fire covering the road and open areas beyond.

Even after the Americans got past the woods and crossed a stream, La Losque (or its tributary, La Losquette), they had a difficult advance uphill in the face of heavy German fire. The topography became much steeper near La Rillerie, gaining about 140 vertical feet over about half a mile’s climb to the summit of Hill 63.

It is unclear when on July 16 that Private Bukowski joined Company “A,” since available records suggest 1st Battalion was fighting or moving from midmorning on. Either way, he must have gone into the fray almost immediately. The 60th Infantry’s after action report stated that the regiment resumed its advance at 0900 hours. Although the main objectives were to the south, the 60th Infantry first had to deal with the German threat to the east:

The 2nd Battalion was receiving fire from its left flank and the 3rd Battalion and 1st Battalion were heavily engaged to their fronts. Little progress was made during the morning. At about 1300 Major (then Captain) [Stephen W.] Sprindis took command of the 1st Battalion. Company “C” aided on its right by Company “E” attacked east and captured the high ground in the vicinity of Oliverie. Tanks were sent ahead and drove the enemy out of Sadoc. A gap existed on the Regiment’s left flank and it is probable that the enemy driven out of Sadoc went across the Regimental Boundary. At about 2100, the 1st Battalion had turned south and was in the far edge of the woods [Bois des Landes] south of Sadoc. An enemy group believed to have been previously driven out of Sadoc counterattacked the left rear of the Battalion’s position, but was repulsed.

The men of 1st Battalion dug in, but got little rest, as they “continued to be engaged throughout most of the night.”

The regimental after action report stated that the following morning, July 17, 1944:

The 1st Battalion reached the 689 grid and was unable to advance further because of fire from Hill 63. The leading company was receiving heavy casualties and in order to assist their advance the 2nd Battalion was ordered to attack east toward La Rillerie (412685 [49° 09’ 43” North, 1° 12’ 46” West]). This action was very successful and the 1st Battalion with the 2nd Battalion abreast was enabled to move forward to the southern limits of their objective. The 1st Battalion sent a patrol to the [Périers] – St. Lo Road.

The Company “A” morning report for July 17, 1944, stated that the company advanced about one mile that day. They then took up defensive positions until July 19, 1944, when 1st Battalion was pulled out of the line and went into reserve.

As far as contemporary unit records were concerned, Private Bukowski survived his first three days of combat unharmed and made it through another period of combat during Operation Cobra later that month. On July 29, 1944, when 60th Infantry Regiment went to a rest area to partake in those simple luxuries that were impossible for infantrymen in combat—showers, clean clothes, and hot meals—nobody noticed that one of the new replacements was not with them.

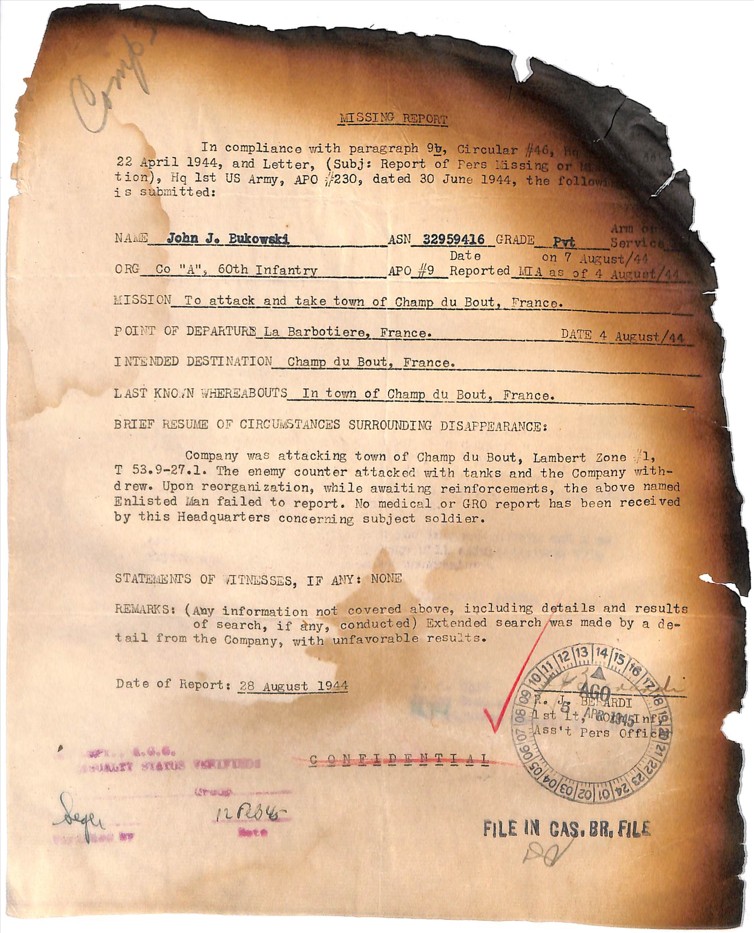

Bukowski was finally reported missing in action only on August 7, 1944, backdated to August 4, 1944. His unit submitted a statement that claimed that on that day:

Company was attacking town of Champ du Bout, Lambert Zone #1, T 53.9–27.1 [48° 47’ 43” North, 1° 00’ 49” West]. The enemy counter attacked with tanks and the company withdrew. Upon reorganization, while awaiting reinforcements, the above named Enlisted Man failed to report.

In fact, Bukowski had been separated from his unit, severely wounded, and captured, no later than July 20, 1944.

A Series of Mysteries

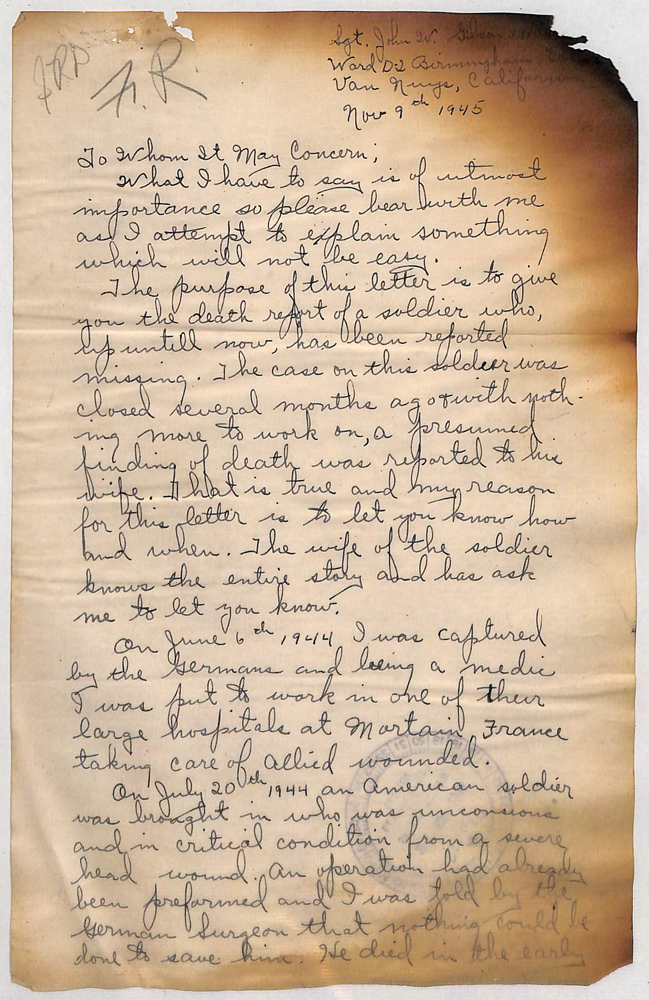

On July 20, 1944, a badly wounded American prisoner of war was brought into a German hospital at Mortain, France—30 miles south of where Private Bukowski had been fighting—and turned over to the care of Technician 5th Grade John W. Gibson (1921–2010). Gibson, an Arizona barber turned surgical technician (medic) had parachuted into Normandy with the Medical Detachment, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Infantry Division, before he was captured at dawn on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Rather than transporting him to a prisoner of war camp, the Germans brought Gibson to Mortain and put him in a ward where he treated Allied wounded.

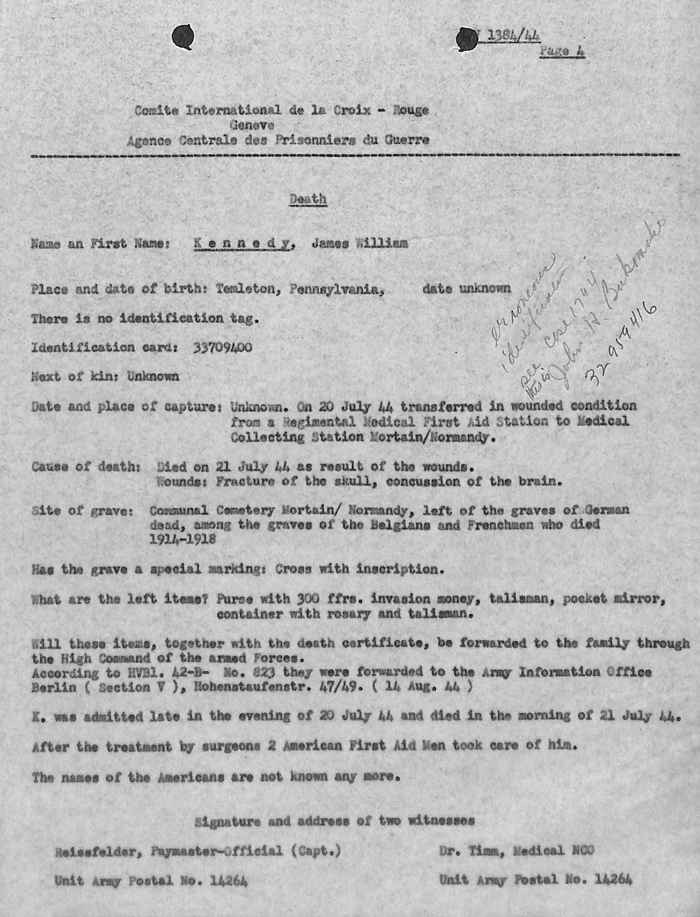

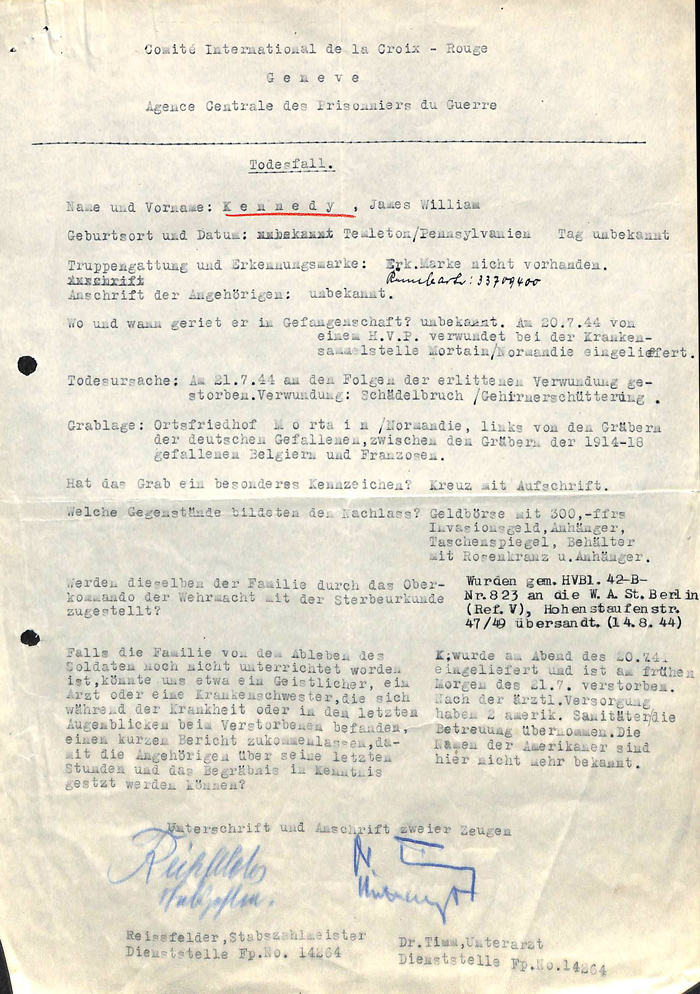

Oddly enough, though the patient was not wearing any dog tags, he had a paybook and two receipts identifying him as John Bukowski. However, in his pocket was a wallet belonging to James William Kennedy (1916–1944). Private Kennedy, a native of Templeton, Pennsylvania, was another replacement rifleman who had joined Company “A” on the same day as Bukowski.

Gibson later recalled that his unidentified patient “was unconscious and in critical condition from a severe head wound. An operation had already been performed and I was told by the German Surgeon that nothing could be done to save him.”

German records do not disclose where or when the unidentified patient was captured, but since he was first treated at a German regimental first aid station and then transferred to Mortain, he was probably wounded before or shortly after capture.

The patient died without regaining consciousness around 0400 hours the morning of July 21, 1944. The next question was which name he should be buried under. The soldier wore dentures, but without access to either man’s medical records, that was of no immediate help in distinguishing them. He also had a rosary and pendant on his person. Gibson discussed the matter with a German sergeant and they concluded

that it was most lodgical [sic] that a man would be carrying another fellows pay book but hardly a wallet so we chose Kennedy’s name for the cross. He was given a nice burial in the French cemetery on the hill above Mortain, France. His g[r]ave lies among the French soldiers who were buried in 1940.

Gibson was uneasy about the identification. He recorded both men’s names and next of kin in his notebook. After he was liberated on August 4, 1944, Gibson reported his uncertainty to the Army on two separate occasions, though it does not appear any action was taken based on those tips. However, the mystery continued to gnaw at him. After returning to the United States, he wrote to Bukowski’s wife and Kennedy’s mother. Both women mailed him photographs of their loved ones. Based on the photos, Gibson identified the patient as Private Bukowski.

There are many mysteries about what happened to Private Bukowski in Normandy, some of which remain unsolved. The circumstances of his capture are unknown, though it almost certainly occurred during July 16–19, 1944. It is unclear if it happened while he was participating in the American attacks on July 16 or 17 or in a German counterattack around that time. Although there is only the slimmest circumstantial evidence to support it, it is most likely that he was captured during the first day or two. Not only was the fighting at its heaviest during those days, but it also seems more plausible that Bukowski’s disappearance would go unnoticed during those chaotic two days than if he had been part of a squad for a longer period.

There are many possibilities about how Bukowski fell into German hands, all of which are plausible but none of which are supported by any real evidence. He could have been wounded and captured during an attack that the Germans repulsed, or when a German counterattack overran his position. It is also possible that he could have gotten separated from an American patrol or nabbed by a German patrol seeking prisoners for intelligence purposes. It is unclear if he was wounded in battle before or after his capture. A German patrol would probably not have dragged an unconscious American back to their lines. Not only would that have been difficult and dangerous for the Germans, but a man with a mortal head wound could not be interrogated. However, it is plausible that if Bukowski was not already wounded before his capture, he could have been wounded by artillery or aircraft after he was captured.

At the end of the war in Europe, with no burial report, no evidence of him being a liberated prisoner of war, and no plausible explanation for Private Bukowski having survived without being accounted for, the War Department had issued a finding of death in accordance with Public Law 490, making his presumed date of death August 5, 1945, a year and a day after his reported disappearance.

On November 9, 1945, Gibson, now a sergeant stationed at Birmingham General Hospital in Van Nuys, California, wrote to the Army explaining his conclusion that his patient had been Bukowski, not Kennedy. The Adjutant General’s Office wrote back to Gibson, initially refusing to reopen the case:

In view of the fact that the soldier, whom you identified by pictures as Private John J. Bukowski, entered the German hospital two weeks before Private Bukowski became missing in action, this office is unable to take further action to amend the records of this soldier. Therefore, it would be greatly appreciated of [sic] you would assist in clarifying the discrepancies concerning the actual date of death. Information is particularly desired as to how you established the fact that the soldier you have identified as Private Bukowski was brought to the hospital on 20 July 1944, and whether it is possible that the date might actually have been 4 August 1944.

An exasperated Gibson, who had been discharged from the Army on December 4, 1945, and returned home to Tucson, Arizona, repeated his story, explaining: “I kept notes while a prisoner and have them beside me now. By these notes I am able to give you exact dates, names, etc.”

Gibson added: “Not only did I recognize the pictures but Mrs Bukowski confirmed the false teeth.” He recalled clearly that the dentures rattled audibly as the patient was dying. Kennedy, he added, was younger than Gibson’s patient, had darker and thicker hair, and did not wear dentures. Gibson concluded:

The only obvious reason the case was not re opened after the arrival of my first letter was that Bukowski was not reported missing untill [sic] Aug 4th. Here is the only answere [sic] to that. In my regiment as in all regiments a complete check of all men is nothing short of impossible during the heat of battle. This all happened during the terrible battles about the time of the St Lo breakthrough. It was probably not untill Aug 4th that Co A was able to turn in a thorough report.

Gibson added that he was certain that he did not treat Bukowski on August 4, 1944, because that was the very day he was freed by Allied forces, and by then Gibson was Rennes rather than Mortain.

Gibson was certainly correct about the difficulty of recordkeeping during combat, and a reporting delay of a few days could easily be explained. Bukowski’s date of death was by no means the only fallen Delawarean whose official date of death was suspect. A remarkable number of men’s dates of death coincide with their unit being pulled out of the line. While some soldiers certainly did become casualties on the very day their unit went into reserve, in at least some cases that was simply the date that accounting for losses became possible.

When a soldier was reported as casualty under such circumstances, it was possible to backdate the casualty if the date of loss was known. However, if it was not, a soldier’s date of death was never recorded as a potential range of dates. A single date had to be submitted, and in some cases that was the report date. In many cases of discrepancies of date of death, the interval between the official date of death and probable date of death was rather small. Often this was a day or two, maybe three days. However, longer intervals of poor recordkeeping did happen.

A 1944 memorandum from the Mediterranean Theater excoriated company grade officers and noncommissioned officers, stating in part: “Proper accounting of personnel is a command function.” Although the memo was from another theater, it discussed similar mistakes to what happened in Bukowski’s case:

a. In one case, a soldier was actually carried present for duty on the roster of his organization for five weeks when actually he was missing in action. No remark was ever made on the morning report of his organization until the error was discovered by an audit of personnel conducted by the Personnel Officer. This indicates that no physical check of personnel was made against the roster of that organization for five weeks. A soldier who is not present for duty during combat must be absent. If his absence is not accounted for, he must be missing in action. If he is missing in action, he must be reported as such within 72 hours. To carry a man erroneously for five weeks indicates lack of supervision and is inexcusable.

b. In several instances, men have been reported on morning reports as missing in action, or killed, 10 to 15 days after the incident occurred. This means that for a period of from 10 to 15 days, daily checking of personnel had not been made by squad leaders, platoon sergeants, and first sergeants.

Indeed, strong circumstantial evidence indicates that in the heat of battle, an inexperienced new replacement, possibly already wounded, fell into the hands of the enemy, and after that happened, his absence was neither noticed nor reported for over two weeks. His company spent several days in reserve before Operation Cobra and then went to a rest area on July 29, 1944, so there was time to account for the unit’s losses. According to Company “A” morning reports, its overall casualties were not especially high during July 16–20, 1944, but losses among its senior noncommissioned officers were. The 1st sergeant—whose duties included accounting for personnel and preparing company morning reports—and two of the four platoon sergeants became casualties. The company clerk was supposed to check morning reports for accuracy, but if nobody submitted a casualty report, he would be none the wiser, at least until it was time to do the monthly payroll and Bukowski failed to sign.

Finally, around December 13, 1945, the Casualty Branch reopened Bukowski’s case. Investigators soon discovered that there were two burial reports for Private James W. Kennedy. Private Kennedy was reported killed in action as of August 3, 1944, and buried the following day in Marigny, France. This man was found wearing Kennedy’s dog tags. This was the real Private Kennedy.

Investigators found a second burial report for a “James W. Kennedy” found buried without dog tags in Mortain under a cross bearing the date of death of July 21, 1944, and reburied at a U.S. military cemetery at Saint-James, France, on September 6, 1944. On March 14, 1946, the body was exhumed and assessed forensically as an unknown soldier. The findings precisely matched Gibson’s recollections and were also consistent with Bukowski’s physical characteristics. The investigator, Theodore T. Edwards, described the deceased man as being about 35 years of age, with an estimated weight of 160 lbs., and an estimated height of five feet, seven inches tall. He had brown hair. The man had a full set of dentures and deep penetrating trauma to the “sub occipital and mastoid region of [his] skull” which had been covered with a dressing. Based on these findings, the Army accepted this man was indeed Private Bukowski.

How Bukowski ended up with Private Kennedy’s wallet in his pocket was never explained. They were in the same company, and the fact that Kennedy was reported killed in action the day before Bukowski’s absence was noticed is certainly a remarkable—and perhaps suspicious—coincidence. However, there is no indication that Kennedy was captured at the same time.

The following year, Jeanette Bukowski requested that her husband remain buried in a permanent military cemetery overseas. In accordance with her wishes, Private Bukowski was reburied at the permanent Saint-James cemetery, now known as the Brittany American Cemetery.

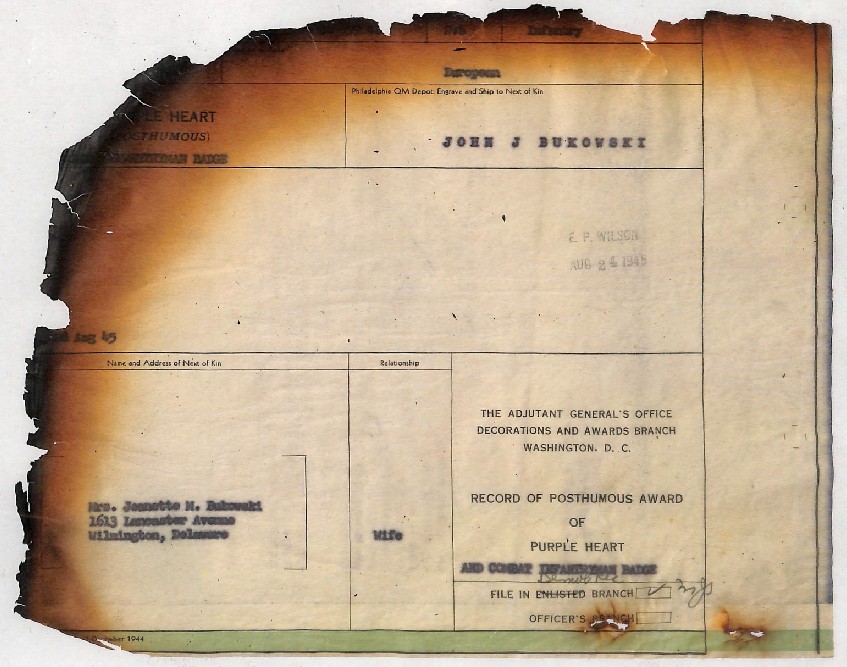

Bukowski had a clean disciplinary record and was favorably considered for the Good Conduct Medal, though he would have needed to spend a year on active duty to earn it. Bukowski was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

Notes

Date of Birth

Bukowski’s draft card and military records list his date of birth as October 21, 1912. Curiously, his father’s petition for naturalization, dated March 4, 1913, stated that Bukowski was born on February 21, 1912. Although both sets of sources gave his place of birth as Wilmington, Delaware, there appears to be neither a Delaware birth certificate nor an entry in the Wilmington birth register for him. However, registering births was not required by Delaware law until July 1, 1913.

John W. Gibson

Gibson resumed his work as a barber after returning to Tucson. In 1949, he purchased what became the Johnny Gibson Barber Shop, which he would run for the next 52 years. He is still a legend fondly remembered by many in Tucson.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jean-Paul Pitou for his research into and photos of Sadoc and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“Alexander Bukowski.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/108312026/alexander-bukowski

“Alexander Bukowski.” Journal-Every Evening, March 6, 1956. https://www.newspapers.com/article/185014041/

Balkoski, Joseph. Beyond the Beachhead: The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2005.

Bukowski, Stella. Individual Military Service Record for John J. Bukowski. April 10, 1947. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17907/rec/11

Census Record for John Bougckski [sic]. January 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR6W-936

Census Record for John Bukoski [sic]. April 8, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRH9-SNP

Certificate of Birth for Josephine Puwalska. May 1, 1916. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6XH9-NTW

Certificate of Marriage for John Joe Bukowski and Jeanette Josephine Makouska. February 7, 1937. Record Group 1500-008-093, Marriage Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-XMM9-Y4T

“Corporal Gibson is Reported Safe.” The Arizona Daily Star, August 25, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/185722951/

“Diehststelle Feldpost No. 14264.” August 25, 1944. German Amerikaner Vorgaenge (AV) Reports, 1943–1945. Record Group 242, National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, 1675–1958. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/opastorage/live/66/3553/17355366/content/dc-metro/rg-242/6919353_A1-1011/6919353_Box116_Folder6/6919353_Box116_Folder6.pdf

Draft Registration Card for John Joseph Bukowski. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-XS85-1

Enlistment Record for John J. Bukowski. October 20, 1943. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32959416&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3454889

Escape and Evasion Report for John W. Gibson. August 10, 1944. Escape and Evasion Reports, 1942–1945. Record Group 498, Records of Headquarters, European Theater of Operations, United States Army (World War II), 1942–1947. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5555602

Indenture Between Ella Lavinia Forman, Party of the First Part, and Alexander Bukowski and Stanislawa Bukowski, Parties of the Second Part. October 4, 1912. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_256884-00629

Indenture Between Samuel F. Usilton and Anna H. Usilton, Parties of the First Part, and Alexander Bukowski and Stanislawa Bukowski, Parties of the Second Part. March 25, 1924. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_256992-00227

Individual Deceased Personnel File for John J. Bukowski. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Johnny Gibson 1921 – 2010.” Arizona Daily Star, June 6, 2010. https://www.newspapers.com/article/185723213/

Marries, Dan. “Meet Johnny Gibson, One of Tucson’s ‘Living Legends’.” 13 News, November 21, 2005. https://www.kold.com/story/4145744/meet-johnny-gibson-one-of-tucsons-living-legends/

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 60th Infantry Regiment. July 1944 – August 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-07/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0769/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0769-11.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-08/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0614/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0614-13.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “E,” 115th Infantry Regiment. August 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-08/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0595/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0595-26.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “E,” 115th Infantry Regiment. June 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-06/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0668/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0668-05.pdf

Official Military Personnel File for John J. Bukowski. Official Military Personnel Files, 1912–1998. Record Group 319, Records of the Army Staff. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Petition for Naturalization for Alexander Bukowski. March 4, 1913. Naturalization Petitions of the U.S. District and Circuit Courts for the District of Delaware, 1795-1930. Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1193/images/M1644_10-0822

Prisoner of War Data for Henry J. Bulowski. World War II Prisoners of War Data File, December 7, 1941 – November 19, 1946. Record Group 389, Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=3159&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=bukowski%23henry&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=10556

“Pvt James William Kennedy.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17376418/james-william-kennedy

“Regimental History 60th Infantry Regiment. 1 to 31 July 44.” August 9, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Unit Army Postal No. 14264.” Original August 25, 1944, date of translation unknown. Translations of German Amerikaner Vorgaenge (AV) Reports, September 1944–February 1945. Record Group 242, National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, 1675–1958. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/opastorage/live/74/2385/18238574/content/dc-metro/rg-242/6922023_A1-1012/6922023_Box124_Folder3/6922023_Box124_Folder3.pdf

Last updated on December 31, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.