| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| New Castle, Delaware | Laborer |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32065604 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “E,” 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 675 (messenger) as of September 1942 | Operation Torch |

Author’s note: This article includes text from my previous profile about Staff Sergeant George Isadore (1909–1942), who also participated in Operation Torch.

Early Life & Family

Edgar Walker Stevenson was born on February 26, 1919, on East 4th Street in New Castle, Delaware. He was the son of Thomas William Stevenson (a steel worker, c. 1883–1938) and Emma Stevenson (née Emma Ruth Lynam, c. 1889–1983). He had an older half-brother from his father’s first marriage, two older brothers, and an older sister.

Stevenson was recorded on the census in January 1920 living at 156 North 4th Street in New Castle with his parents, maternal grandmother, and four older siblings. (Almost certainly, this address is the same as 156 East 4th Street.) His father was described as a molder at a steel factory.

On June 21 and 22, 1923, Stevenson’s parents purchased a pair of parcels of land on East 6th Street in New Castle. Stevenson was recorded on the next census in April 1930 living at 16 East 6th Street in New Castle with his parents, siblings, and maternal uncle. Both his parents were described as working in a silk mill: his father as a mechanic and his mother as a helper. His uncle and older half-brother were working in a shipyard. Shortly after Stevenson turned 19, his father died of lobar pneumonia in St. Francis Hospital in Wilmington, Delaware, on March 8, 1938.

When the next census was taken in April 1940, Stevenson was living at home with his mother, two siblings, and his sister-in-law. The entry stated that his highest education level was the 7th grade and described him as unemployed since at least 1938, though he had last worked as a laborer in the tanning industry. Stevenson was also unemployed when he registered for the draft on October 16, 1940. The registrar described him as standing five feet, 11 inches tall and weighing 151 lbs., with blond hair and blue eyes. On the other hand, Stevenson’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) has a document that described him as standing five feet, 9½ inches tall and weighing 151 lbs., with sandy hair and gray eyes. He was Protestant.

The Wilmington Morning News reported that Stevenson “attended the William Penn School and was a member of the New Castle Methodist Church.”

Military Training

Stevenson was drafted before the United States entered World War II. He was inducted into the U.S. Army on January 10, 1941, in Trenton, New Jersey. He went on active duty the same day and was briefly attached unassigned to Company “A,” 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey. By January 13, 1941, he had been classified and his name added to a transfer list for men earmarked for the 9th Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. At the time, many soldiers were assigned directly to their future units for basic training rather than attending at a training center. He departed Fort Dix on or about January 16, 1941.

On January 17, 1941, Stevenson joined Company “E,” 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Division, at Fort Bragg. A morning report suggests that he and his cohort finished their basic training on March 10, 1941. During June 4–8, 1941, the 60th Infantry Regiment faced off against the 44th Division in maneuvers near Bowling Green, Virginia, presumably at the new A.P. Hill Military Reservation, then returned to Fort Bragg on June 9.

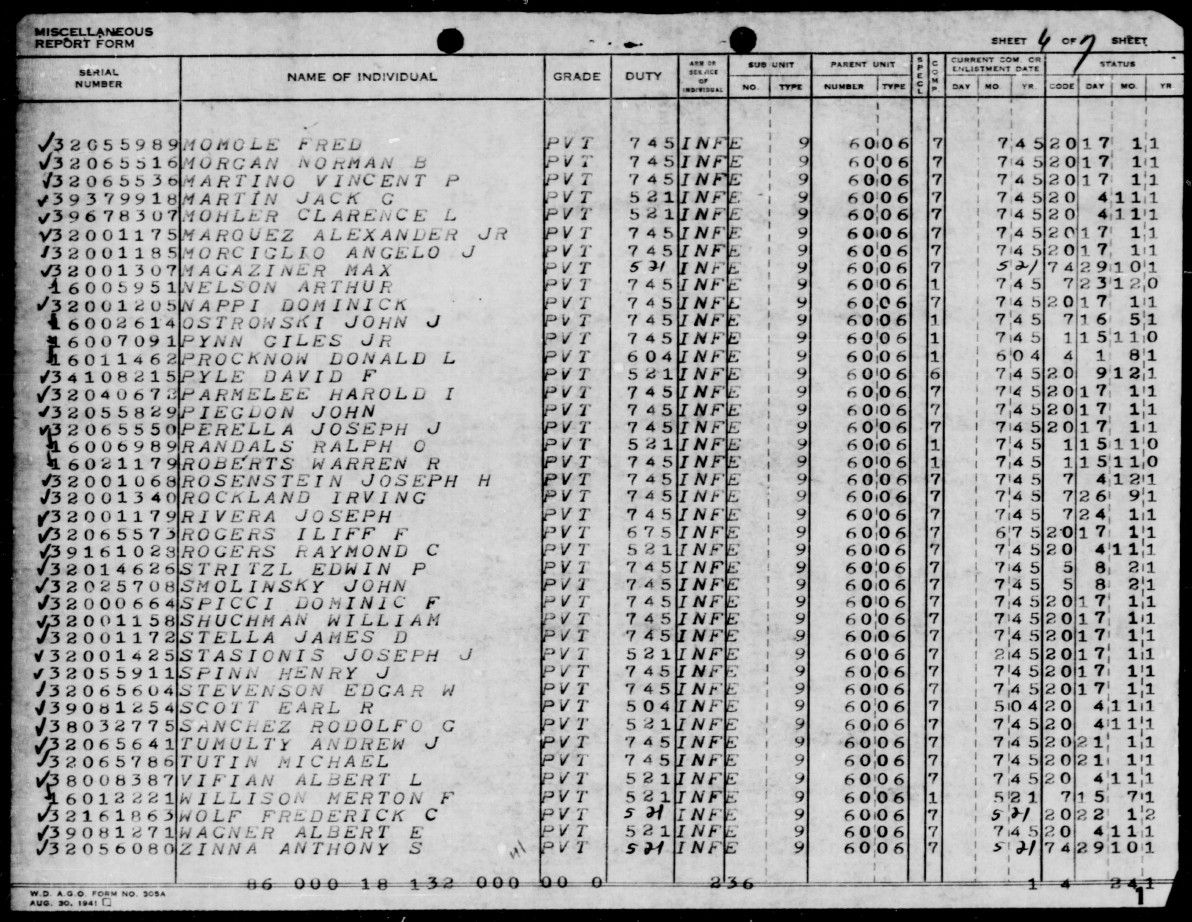

The July 1941 roster, the earliest to list duty codes, listed Stevenson’s as 745, rifleman. Private Stevenson went on furlough during September 16–22, 1941. Two days later, his unit departed Fort Bragg to participate in the Carolina Maneuvers. They remained in the Carolinas until at least November 28, 1941. Company “E,” morning reports are a little unclear, but the unit may have returned to Fort Bragg afterwards. Regardless, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into World War II, morning reports indicate that the company was on guard duty in Tennessee during December 16–31, 1941. The company also pulled guard duty at Robbinsville, North Carolina, January 1–6, 1942, before returning to Fort Bragg that afternoon.

Beginning with the January 1942 roster, both Private Stevenson’s duty and military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) codes were recorded as 745, rifleman.

According to a contemporary regimental history:

About February 1st, 1942 the 9th Division was motorized. The 60th Infantry received half-tracks and began training as a motorized regiment until around March 1st when the division was changed from a motorized division to an amphibious division. During the period from about March 1 until the fall of 1942, the regiment trained intensively along amphibious lines.

This suggested that Army planners intended to give the 9th Division a similar mission to those divisions fielded by the Marine Corps. During the war, the U.S. Army performed many more amphibious operations than the Marine Corps, but the concept of a specialist Army amphibious division did not stick and despite its specialist training the 9th Infantry Division ended up performing just a single amphibious operation during the war.

On or about April 28, 1942, Private Stevenson went on furlough. The following day, Journal-Every Evening reported on April 29, 1942, that he was “visiting his mother, Mrs. Emma Stevenson, Sixth and Cherry Streets.” As a result, he did not accompany his unit to Norfolk, Virginia, where they boarded a ship to perform amphibious training at Solomons Island, Maryland. He returned to duty on May 6, 1942. The main body of his unit returned to Norfolk on May 6 and to Fort Bragg early on May 8.

At 1700 hours on May 15, 1942, Stevenson and his company boarded a train to head north again, arriving at Norfolk at 0130 the next morning. At 0900 hours that morning they sailed aboard the attack transport U.S.S. Leonard Wood (APA-12). After six days of amphibious training, they returned to Norfolk on the evening of May 22. The following morning they headed south by train, arriving at Fort Bragg at 1800 that evening.

The company roster dated May 31, 1942, reflected a change in Stevenson’s duty and M.O.S. to 675, messenger. The following month, on June 13, 1942, Private Stevenson and his unit departed Fort Bragg by road, en route to Onslow Beach, North Carolina. During June 15–19, 1942, they performed additional amphibious training at New River, North Carolina, a Marine base later known as Camp Lejeune. They returned to Fort Bragg on June 20. On the Fourth of July, they marched in a parade in Salisbury, North Carolina. On July 18, 1942, Stevenson and his company again headed to Norfolk. The following morning, they boarded the transport U.S.S. Joseph Hewes (AP-50). They spent July 20–29, 1942, performing exercises at Solomons Islands, Maryland, before returning to Norfolk on July 30 and Fort Bragg on July 31.

The 9th Division was redesignated as the 9th Infantry Division effective August 1, 1942. Later that month, on August 18, 1942, Private Stevenson went on a special duty assignment with the division’s Military Police platoon. He returned to duty with Company “E” on August 26, possibly catching part of yet more amphibious training at New River during August 24–28. He was still listed as a messenger in the September 1942 roster, the last one available to list duty and M.O.S. codes.

Operation Torch

Immediately after the U.S. entry into World War II the Americans agreed with the British to prioritize victory in Europe over the Pacific. It soon became clear that it would be impossible to build up enough forces and amphibious capacity to launch a direct attack on Nazi-occupied Europe in 1942. Even so, there was intense pressure to get American forces into the fight and to relieve pressure against the Soviet Union by forcing the Axis to commit resources to other fronts. During the summer of 1942, Allied planners began preparing Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa.

Ironically, the first American offensive in the Mediterranean Theater would strike not the German or Italian armies, but the nominally neutral forces of America’s “oldest ally.” France’s colonies in North Africa were under the control of Vichy France, essentially an Axis-aligned rump state established after the defeat of France in 1940. Secret negotiations between the Americans and French proved fruitless prior to Torch. Simultaneous landings targeting French possessions in Morocco and Algeria would begin early on November 8, 1942.

For Operation Torch, the 60th Infantry Regiment was detached from operational control of the 9th Infantry Division and placed in Sub-Task Force Goal Post (or Goalpost) under the command of Brigadier General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. (1895–1965). The 60th Infantry Combat Team, with attachments including armored and antiaircraft units, would land at Mehdia (Mehdya), on the Moroccan coast at the mouth of the Sebou River. The main objective was inland, an airfield at Port Lyautey (now Kenitra). Once secure, American fighters would fly from a carrier offshore to the field, where they would support operations nearby.

On October 15, 1942, Stevenson and his comrades again headed to Norfolk for more amphibious training. The following day, they boarded the transport U.S.S. George Clymer (AP-57). The usual amphibious exercises followed at Solomons Island, Maryland. This time, the 60th Infantry would be operating with the same boat crews that they would go into battle with. A regimental history stated:

The first phase of this final training period consisted of net drills conducted with boats to be used for the African landing. All troops went over the side, becoming accustomed to the pitching of the smaller craft in a choppy sea. The cold winds of the Chesapeake were busy, causing rough water — and many a light stomach. Coxswains and other Navy crewman also received valuable training in handling of the heavily loaded craft.

Initial drills were in daylight, but the last, like the planned operation, took place at night. Stevenson’s transport returned to Norfolk on October 22, but sailed again the following day, this time for North Africa.

The 60th Infantry Regiment’s commanding officer, Colonel Frederick J. de Rohan (1893–1993), later wrote that each day while crossing the Atlantic, the soldiers of his regiment rehearsed assembling to board their landing craft. Remarkably, the men of the 60th Infantry even received mail at sea, delivered by destroyer.

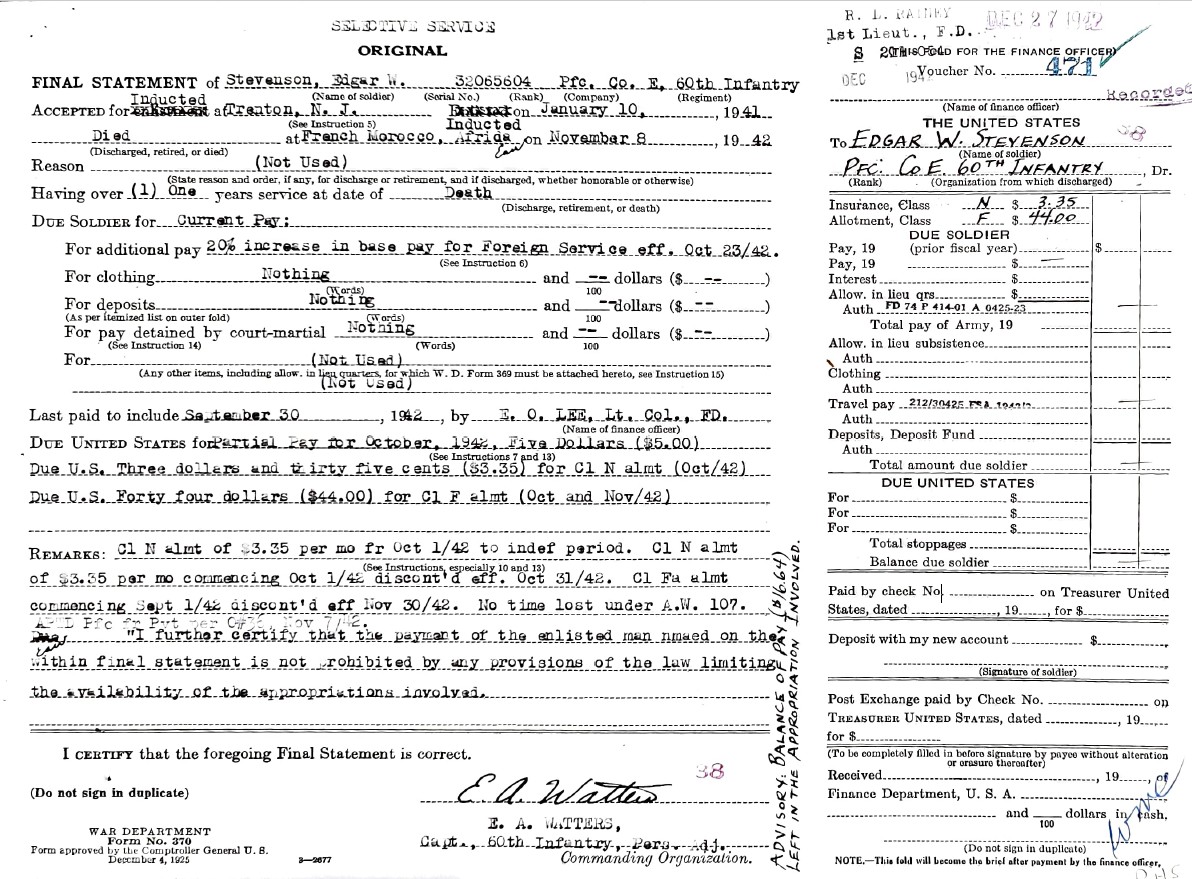

On November 7, 1942, the day before he went into combat for the first time, Stevenson was promoted to private 1st class. Colonel de Rohan wrote:

The plan for the capture of the position known as the Kasba and which commanded the entrance to the Sebou River called for a landing at 0400, an advance to and an assault with the bayonet. This would have given about two hours of darkness in which to have effected reorganization and to have carried out the assault. However because of the lateness in landing which placed the assault waves on the beach about ten minutes before first light, or an hour and fifty minutes late, this plan was not possible of accomplishment.

In preparation for the invasion, the 60th Infantry was split into three battalion landing teams. As was the case with future invasions, landing craft were too small to accommodate a full platoon. Instead, as de Rohan wrote, the battalion landing teams were “organized into boat teams which placed in assault boats part of the heavy weapons units.”

The fleet had crossed the Atlantic without being intercepted by German submarines. However, the 60th Infantry’s landings fell behind schedule. Colonel de Rohan wrote:

The lateness in landing troops can probably be attributed to lack of experience on the part of personnel from the transports, to delays in lowing and assembly of boats from other transports, lack of experience in handling winches and lowering boats, difficulty in getting waves ashore on the right beach and difficulty in landing in heavy surf.

Stevenson’s 2nd Battalion Landing Team was the only one of the three to land at its assigned beach. A report of the 60th Infantry’s operations stated that “The 2nd Battalion landed on GREEN BEACH just prior to first light and was met only be white, red, and green flares.” One report indicated that the first three waves did not receive any enemy fire until they were already on the beach, though some French artillery “fired intermittently on succeeding waves and later two French aircraft strafed the beach with machine gun fire till the arrival of our fighter planes.” Another report stated:

The first boats of the Second Battalion Landing Team reached the beach at Mehdia Plage at about 0540. The assault waves did not encounter enemy opposition until the craft came about 700 yards off shore. A search light from the shore picked up a Navy scout boat and a red flare shot up from the south jetty at the river mouth. This apparently signalled [sic] shore batteries to begin firing for they opened up at the scout boat and other Naval craft. The Destroyer Roe immediately replied with several salvoes and the French fire ceased under this bombardment. No troops were injured in this exchange.

Private 1st Class Stevenson was killed in action on the first day of Operation Torch, November 8, 1942. His I.D.P.F. gave his cause of death as drowning. In his book, An Army at Dawn, Rick Atkinson wrote that “Several landing craft snagged on sandbars or capsized as soldiers rolled over the gunwales in their haste to reach land. Sodden bodies washed ashore, facedown in a tangle of rifle slings and uninflated lifebelts.”

Although it is unknown whether it had anything to do with Stevenson’s death, in the aftermath of the operation Colonel de Rohan advised against the use of the Army’s carbon dioxide-inflated lifebelts. He noted that “it does not hold up the man’s weight nor the man’s head if he is unconscious. The jacket (kapok type) is more practical and should be worn until the men are safely landed on the shore.” The life belt was less bulky than a life vest and de Rohan’s recommendation was not acted upon. Later, especially during the invasion of Normandy, they were implicated in drowning heavily laden troops by forcing their heads down.

Despite their losses offshore, Stevenson’s comrades captured the lighthouse and assaulted but did not take the fortress (kasbah) at the mouth of the Sebou River, which would hold out for another two days.

On November 10, 1942, the old destroyer U.S.S. Dallas (DD-199) with a local Free French pilot aboard, sailed five miles up the Sebou River to deliver a ground force that successfully secured Port Lyautey’s airfield. Later that day, Vichy French forces in North Africa agreed to an armistice.

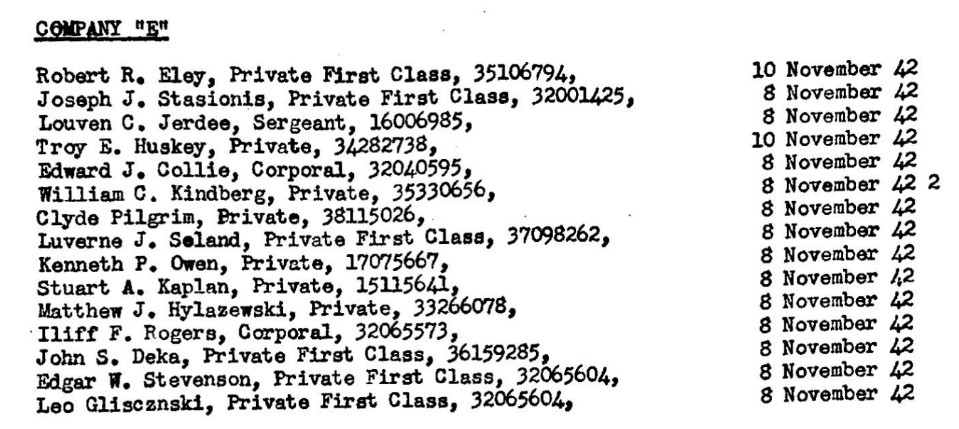

The entire operation at Mehdia–Port Lyautey ended up being largely pointless since the American aircraft arrived too late to participate in Operation Torch and the French capitulation was driven by events elsewhere. The fighting in Morocco and Algeria had been costly. Among the 60th Infantry Regiment’s casualties, Stevenson’s Company “E” was hardest hit with 19 killed, including four officers, and nine enlisted men wounded. (Nine officers from the regiment were wounded but their companies were not disclosed in the report.) Five men from Company “E” including Stevenson drowned on the first day of the battle.

Herder wrote:

Torch’s November 8–10 combat is too often dismissed as a historical footnote. Yet in three days defending North Africa against the Anglo-Americans, the French had suffered 3,343 casualties, including 1,346 killed. When including French- and Axis-inflicted naval losses, total Allied combat casualties climb to 2,661, including 1,331 killed or missing – fully 30 percent that suffered by the lionized June 6, 1944 Normandy landings.

Operation Torch’s aftermath was bittersweet. Many former Vichy French soldiers now joined the Allies. The Germans quickly occupied the Vichy-controlled areas of mainland France. As Herder observed, “The Vichy state was fully revealed as the political fraud it had always been.” Neither side claimed the bulk of the French fleet at Toulon, its ships scuttled by their crews before the Germans could seize them. German reinforcements flowed into Tunisia, ensuring that combat would continue in North Africa for another seven months, though the subsequent Tunisian campaign ended with a resounding Allied victory.

The Wilmington Morning News reported on December 16, 1942, that the day before, Stevenson’s mother was notified of his death.

Journal-Every Evening reported on January 30, 1943:

Tomorrow afternoon at 3 o’clock at a meeting in the auditorium of the William Penn School, New Castle’s first casualty in the war, Edgar W. Stevenson, is to be honored by dedicating the Aircraft Warning Service Post to him. John G. Leach will be speaker of the day. […]

At the morning service in the New Castle Methodist tomorrow a gold star will be placed on the service flag of that congregation in honor of Edgar W. Stevenson.

On February 9, 1943, the paper stated:

Mrs. Emma Stevenson, mother of Edgar Walker Stevenson, has received the Order of the Purple Heart which was awarded to her son for valor in action. The name of Private Stevenson is engraved on the back of the decoration and the date on which he died in defense of his country on foreign soil. Mrs. Stevenson is now wearing the decoration but stated simply “I’d rather have my boy.”

The Aircraft Warning Service observation post has been dedicated to him and named in his honor and the community paid tribute to his sacrifice at a meeting held recently in the William Penn School when Gov. Walter W. Bacon and other officials were present for the ceremonies.

Private 1st Class Stevenson was initially buried at a temporary cemetery at the kasbah on November 8, 1942. He was subsequently reburied at another cemetery in Casablanca, Morocco. In 1947, Stevenson’s mother requested that her son’s body be buried in a permanent cemetery overseas. All the temporary American military cemeteries across the continent were consolidated at a single cemetery in Tunisia, today known as the North Africa American Cemetery.

Journal-Every Evening reported that Stevenson’s name was honored on a plaque to the “nine former pupils of William Penn School who lost their lives in World War II” unveiled on January 30, 1947. He is also honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Notes

1920 Address

There is no extant 156 North 4th Street in New Castle. All the numbered streets have either an east or west prefix depending on which side of Delaware Street they are located on. Stevenson’s father’s World War I draft card gave the address as 156 East 4th Street, which is the correct present day address. The roads actually run from southwest to northeast and southeast to northwest, so it unclear if the north suffix was an error by the census enumerator, an accepted variation at the time, or the suffixes were temporarily changed around 1920.

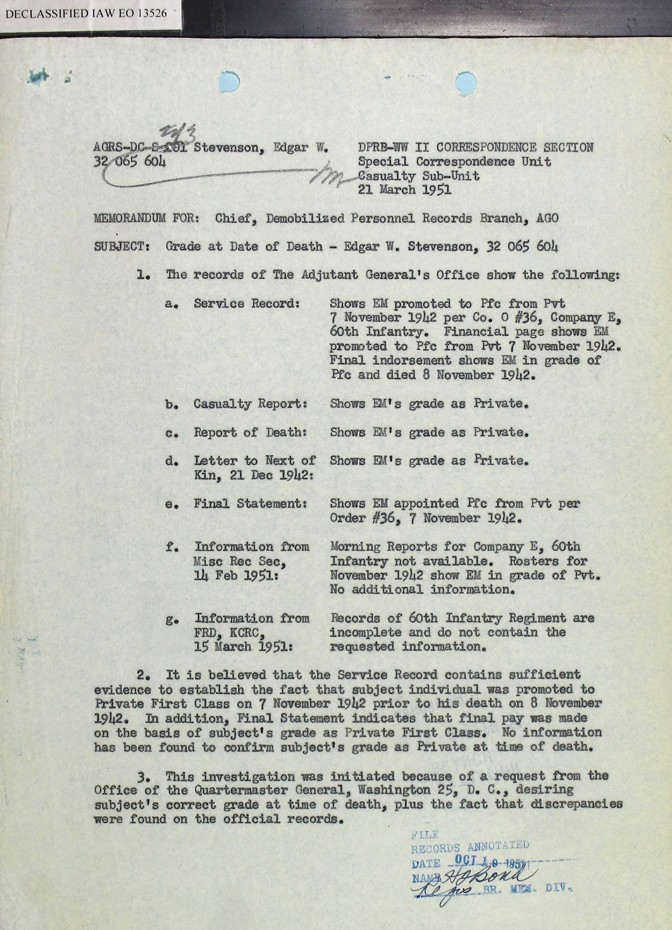

Grade

In 1951, the Office of the Quartermaster General requested an investigation due to a discrepancy regarding Stevenson’s grade at the time of death. A roster and casualty reports showed him as a private. Morning reports from November 1942 were lost before they could be microfilmed and were similarly unavailable to the investigator. On the other hand, Stevenson’s personnel file—subsequently lost in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire—and other documents such as his last pay voucher showed that he had been promoted to private 1st class the day before his death. The investigator concluded that Stevenson’s correct grade was private 1st class.

Service Number and Hospital Admission Card

There are also discrepancies regarding Stevenson’s service number. The 1946 official U.S. Army casualty list has his service number as 32065864. Rosters, morning reports, his mother’s statement, and Stevenson’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) show his service number as 32065604, though one document in his I.D.P.F. originally had the number ending in 864 written but then corrected to the one ending in 604.

A duplicate service number of 32065604 was also issued to Stanley G. Ucinski (1914–2004). In fact, quite a few men who were inducted at Trenton, New Jersey, in January 1941 later had their service numbers reissued to men inducted in Newark, New Jersey, that April.

Regardless of the source of the discrepancy, it led to an inaccurate presentation on Ancestry.com and Fold3 of a hospital admission card belonging to Stevenson. Both sites give the event, in which an infantryman suffered injury due to “Boat, sinking, by mine or result of other and unspecified enemy action” in November 1942 in Morocco as being Ucinski. The original hospital admission card only listed the patient’s service number, not his or her name. To make them easier to find, the genealogy websites added names to the hospital cards by cross-referencing the enlistment dataset. Of course, this proved problematic in the case of duplicates.

Identical diagnoses are listed for the two men from Company “E” initially buried alongside of Stevenson at kasbah, both from his company: Private Matthew Joseph Hylazewski (1920–1942) and Private Clyde Pilgrim (1906–1942). Hospital admission cards were filled out even when a soldier died prior to reaching medical care. No treatment was listed on any of the cards and there is no indication any of the three survived long enough to reach treatment. Hylazewski’s hospital card is also affected by the same problem of adding names to records that originally only had service numbers. Perhaps due to unclear microfilming, his name was digitized into the enlistment record file as “HYLAZE#SKI#MATTHEW#J####”—leading Fold3 to display the card under the name Ski Matthew J Hylaze.

Though Stevenson’s card suggested that his landing craft sank due to enemy fire, though that is not confirmed in other sources. Contemporary 60th Infantry Regiment reports suggest no landing craft were sunk by enemy action. The George Clymer after action report mentions boats being damaged or lost, but indicated that most of those were due to them being stranded on the beach by the receding tide, where they were hit by enemy artillery, not sunk by the French on the way to the beach. The hospital card was encoded with limited choices rather than free text and may simply indicate that the three men drowned during a combat operation, rather than confirming that they died specifically due to enemy action.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo and to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for obtaining Stevenson’s last pay voucher.

Bibliography

Atkinson, Rick. An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942–1943. Abacus, 2004.

Census Record for Edgar Stevenson. January 22, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR69-K2Z

Census Record for Edgar W. Stevenson. April 3, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHM-WD4

Census Record for Edgar W. Stevenson. April 12, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MR-M93G

Certificate of Death for Thomas William Stevenson. March 8, 1938. Record Group 1500-008-092, Death Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMJ-YW3L-6

Certificate of Delayed Birth Registration for Edgar W. Stevenson. February 16, 1943. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DT8H-9S

De Rohan, Frederick J. “Comments upon the operations in the vicinity of Port Lyautey, Africa.” November 15, 1942. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Draft Registration Card for Edgar Walker Stevenson. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-XSJM-X

Draft Registration Card for Thomas W. Stevenson. 1918. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005207030_02098

Enlistment record for Stanley G. Ucinski. April 10, 1941. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32065604&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=2801409

“Final Statement of Stevenson, Edgar W. 32065604 Pfc. Co. E. 60th Infantry.” 1942. Individual Pay Vouchers, c. 1926–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

Headstone Inscription and Interment Record for Edgar W. Stevenson. Headstone Inscription and Interment Records for U.S. Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942–1949. Record Group 117, Records of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1918–c. 1995. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/169033608?objectPage=171#object-thumb–171

Herder, Brian Lane. Operation Torch 1942: The invasion of French North Africa. Osprey Publishing, 2017.

Hospital Admission Card for 32065604. U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/701461177/ucinski-stanley-g-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

Indenture Between Bessie L. King and Richard W. King, Parties of the First Part, and Thomas W. Stevenson and Emma R. Stevenson, Parties of the Second Part. June 21, 1923. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_256979-00275

Indenture Between Mary Clark, Party of the First Part, and Thomas W. Stevenson and Emma R. Stevenson, Parties of the Second Part. June 22, 1923. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_256979-00274

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Edgar W. Stevenson. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Moen, A. T. “After Battle Report – Port Lyautey (Medhia), French Morrocco, Africa, period November 7–11, 1942, inclusive.” November 20, 1942. World War II War Diaries, Other Operational Records and Histories, c. January 1, 1942–c. June 1, 1946. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/134010710

“Monthly Personnel Roster Feb 28 1941 Company E 60th Infantry.” February 28, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604_07.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jan 31 1942 Company E 60th Infantry.” January 31, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604_06.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jul 31 1941 Company E 60th Infantry.” July 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604_06.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster May 31 1942 Company E 60th Infantry.” May 31, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604_06.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Sep 30 1942 Company E 60th Infantry.” September 30, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1604_06.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 1229th Reception Center. January 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2835/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2835-13.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “E,” 60th Infantry Regiment. February 1941 – October 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650-15.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650-16.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650-17.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650-18.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1650-19.pdf

“New Castle School Honors Nine Who Lost Lives in War.” Journal-Every Evening, January 30, 1947. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153327170/

“New Castle Youth Killed in Africa.” Wilmington Morning News, December 16, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153324131/

“News From Nearby Towns.” Journal-Every Evening, January 30, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153326815/

“Operation of 2nd Battalion, November 8, 9, 10, 1942.” November 14, 1942. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Purple Heart Decoration Given Mother of New Castle Hero.” Journal-Every Evening, February 9, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153327616/

“Regimental History, Sixtieth Infantry 1940–1942.” Undated, c. 1943. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Schedule Set For Consumers At New Castle.” Journal-Every Evening, April 29, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153327420/

Silverman, Lowell. “Staff Sergeant George Isadore (1909–1942).” Delaware’s World War II Fallen website. July 21, 2022. Updated June 21, 2024. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2022/07/21/staff-sergeant-george-isadore/

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

Stevenson, Emma R. L. Individual Military Service Record for Edgar Walker Stevenson. Undated, c. 1945. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20962/rec/1

Last updated on December 28, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.