| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Buffalo, New York | Steamfitter |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | R-1735483 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Headquarters Company, 803rd Engineer Battalion (Aviation) (Separate) |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 240 (tire rebuilder) | Bataan (1942) |

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my previous article, Private 1st Class John E. Adams, Jr. (1921–1944), about another member of the 803rd Engineer Battalion (Aviation) (Separate).

Early Life & Family

Andrew Gorman was born in Buffalo, New York, most likely on April 16, 1896. He was the sixth child of Theodore Gorman or Gormann (a millwright, c. 1839–1924) and Catherine Gorman (or Katherine Gormann, née Graf, c. 1860–1936). He had three older sisters, two older brothers, and two younger brothers. Census records state that Gorman’s father was born in Germany (which was not a unified country at the time), immigrated to the United States in 1868 or 1878, and became an American citizen prior to 1900.

During his youth, Gorman moved frequently with his family, though all his known addresses were in Buffalo until he joined the U.S. Army during World War I. The Gorman family was recorded on the federal census in June 1900 living at 1299 East Ferry Street. They were recorded on the 1905 New York census living at 1201 Delaware Avenue. The next federal census, recorded in April 1910, recorded the family living at 2471 Bailey Avenue in Buffalo.

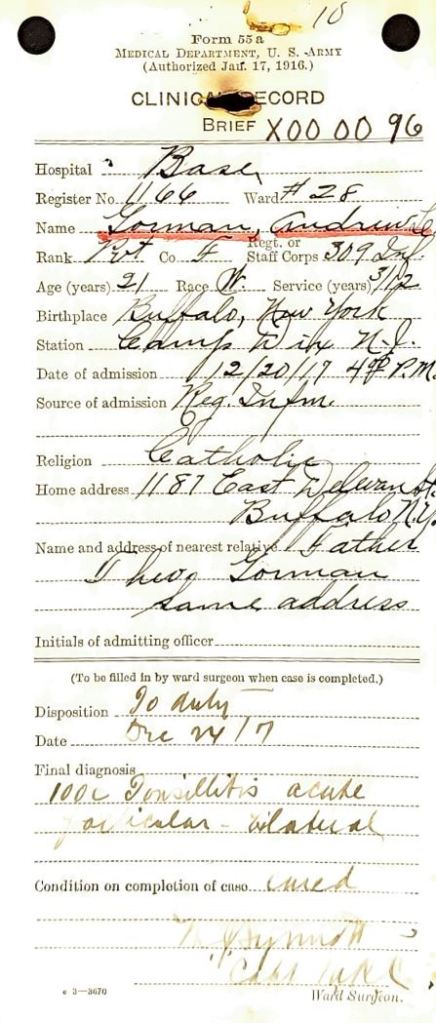

When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, Gorman was back living at 2471 Bailey Avenue in Buffalo and working as a steamfitter for J. H. Ruckel & Son on Main Street. The registrar described him as medium height with blond hair and brown eyes. A clinical record dated December 20, 1917, listed his home address as 1187 East Delevan Street (today Avenue) in Buffalo and his religion as Catholic. However, a later World War II era document stated that he had no religious preference. Census records indicate that he completed one year of high school.

World War I

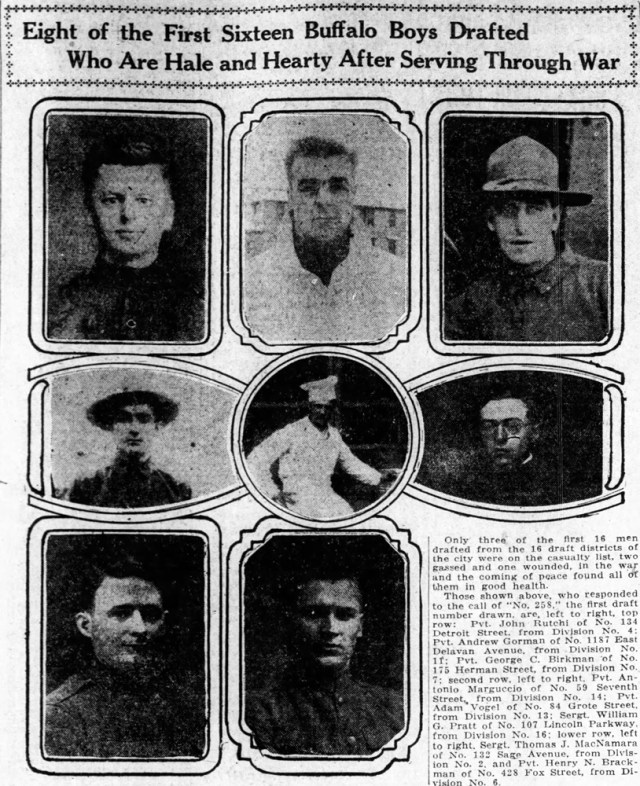

When the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, the country’s armed forces had woefully inadequate manpower and the government implemented conscription for the first time since the Civil War. The Buffalo Evening Times reported that Gorman was one of the men “who responded to the call of ‘No. 258,’ the first draft number drawn[.]” He was inducted into the U.S. Army in Buffalo on September 9, 1917. The following day, at Camp Dix, New Jersey, he joined Company “F,” 309th Infantry Regiment, 78th Division. On December 1, 1917, Private Gorman was appointed to the grade of cook, which under the complicated enlisted rank structure of the era was a separate grade rather than simply a job or military occupational specialty.

Cook Gorman was hospitalized with tonsillitis at Camp Dix on the afternoon of December 20, 1917. He returned to duty four days later. On February 22, 1918, Gorman went on detached service with the 303rd Ammunition Train “pending overseas transfer[.]” On March 20, 1918, he was transferred to the 19th Engineer Regiment (Railway), which was already overseas. He went overseas with the 19th Engineers Camp Dix Reinforcement Detachment from Hoboken, New Jersey, on March 29, 1918, aboard Mount Vernon. It appears he did not immediately join the 19th Engineers, but was assigned to a casual company overseas. On April 27, 1918, he joined Detachment, 1st Provisional Battalion, Railway. He soon transferred to Company “K,” 19th Engineer Regiment (Railway).

Gorman was promoted to sergeant on September 14, 1918, and became a mess sergeant on September 17, 1918. At the time, mess sergeant was a grade of its own, though mess sergeants wore three stripes like a buck sergeant.

In September 1918, his unit was redesignated Company “K,” 19th Regiment, Transportation Corps, and in November 1918, the same month the war ended, it was redesignated again as the 81st Company, Transportation Corps.

Mess Sergeant Gorman sailed from Marseille on March 3, 1919, aboard the S.S. Argentina. He arrived back in New York City on the morning of March 26, 1919. Gorman was briefly assigned to 2nd Company, 152nd Depot Brigade, before he was honorably discharged on April 5, 1919, at Camp Upton, New York.

Interwar Life & Military Career

Gorman was living at 1187 East Delavan Avenue in Buffalo by October 28, 1919, when he married Violet Smith (later Jodd, 1901–1979). She gave birth to their only child, Robert Andrew Gorman (who served in the U.S. Army during World War II, 1919–1990) on December 27, 1919. The trio were recorded on the census in January 1920 living with Violet Gorman’s family at 20 Alma Avenue in Buffalo. Gorman’s occupation was listed as steamfitter in a shipyard. The couple divorced in 1922.

Gorman reenlisted for a three-year term in the Regular Army in 1925. His old rank was not restored, though he worked his way up quickly by interwar standards. Private Gorman joined Company “F,” 1st Engineer Regiment (also known as the 1st Combat Engineer Regiment), at Fort DuPont, Delaware, on February 19, 1925. Gorman was promoted to private 1st class in August 1925. He was reduced back to private in April 1926 but promoted two grades to corporal in July 1926. He was promoted to sergeant in June 1927.

Gorman remarried, to Gertrude Ingram (née Gertrude Shilling, 1895–1985), on an unknown date. He became stepfather to her two children from her first marriage. Their first child, Gorman’s second, was also named Robert Andrew Gorman (1927–1999), and served in the U.S. Army after World War II. Their second child, Joseph Henry Gorman (1936–2023), served for decades in the National Guard. Gorman’s wife and family resided at 915 Gray Street in New Castle, Delaware.

Sergeant Gorman transferred to Company “D,” 1st Combat Engineer Regiment at Fort DuPont on May 16, 1928. He was promoted to staff sergeant on February 9, 1931. Gorman was honorably discharged on February 16, 1931, at the end of his term of service, but reenlisted the following day. On February 20, 1931, he began a 60-day furlough. On April 11, 1931, while still on furlough, he was transferred to Headquarters 2nd Battalion, though he was temporarily attached to Company “D.”

On May 1, 1931, Gorman went on detached service to the Engineer Detachment, Philippine Department. On May 5, 1931, he sailed from New York aboard the U.S.A.T. U. S. Grant, bound for San Francisco, California. He continued his journey from San Francisco aboard the same ship on May 27, 1931, with intermediate stops in Honolulu, Hawaii, and at Guam. Effective June 15, 1931, while still in transit, he was officially transferred to the Philippine Department.

On June 18, 1931, Staff Sergeant Gorman joined the Department Engineer Detachment, Headquarters Philippine Department, Fort Santiago, Manila, Philippine Islands. The detachment had only 20 enlisted men, all of them noncommissioned officers, as of June 30, 1931. Gorman was hospitalized at Sternberg General Hospital in Manila on July 7, 1931. He returned to duty on August 8, 1931. Staff Sergeant Gorman’s term of enlistment ended on February 16, 1934. He reenlisted the following day.

On March 18, 1934, Gorman departed from his unit on detached service to the United States. After arriving back in the country, he went on furlough beginning on April 13, 1934. On May 26, 1934, Staff Sergeant Gorman was transferred to Company “C,” 1st Engineers, but remained on furlough. At the end of his furlough on June 25, 1934, Gorman joined the unit at Camp Dix. He temporarily remained on detached service at Camp Dix on November 26, 1934, when the rest of the unit returned to Fort DuPont. He rejoined the company at Fort DuPont on December 6, 1934. Gorman went on furlough from December 24, 1934, until January 8, 1935; June 16, 1936, until July 9, 1936; and October 10–20, 1936, which followed the death of his mother.

The Wilmington Morning News reported on December 13, 1935, that Staff Sergeant Gorman was an assistant instructor in a plumbing class for soldiers at Fort DuPont.

Staff Sergeant Gorman reenlisted on February 17, 1937. The following day, he began a 30-day furlough. He returned to duty on March 20, 1937, and went on detached service in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from March 29, 1937, until April 1, 1937.

Staff Sergeant Gorman served with Company “C,” until the 1st Engineer Regiment was broken up on October 11, 1939. The following day, he joined the newly activated 70th Engineer Company (Light Ponton), which used pontoon bridges to cross bodies of water. He went on furlough during October 21–29, 1939. Gorman was promoted to technical sergeant effective November 8, 1939.

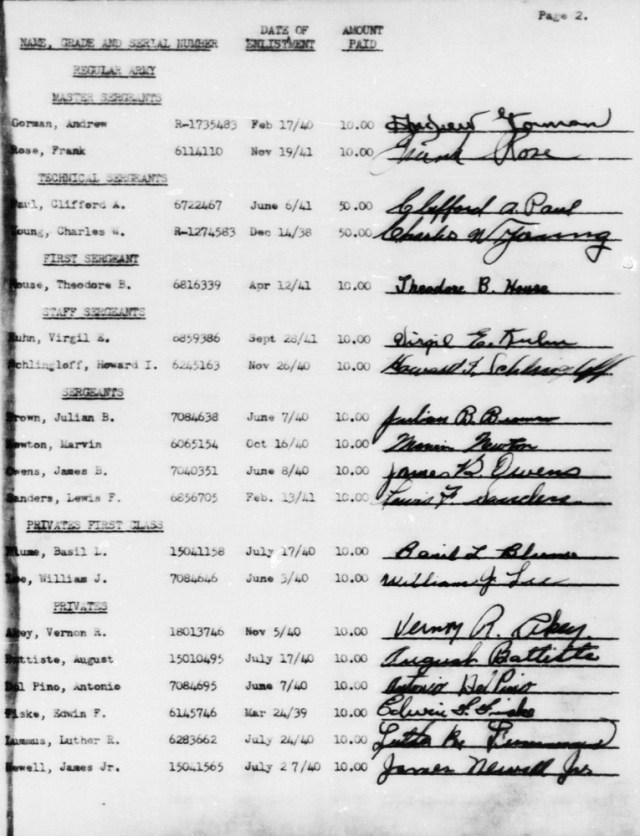

Technical Sergeant Gorman was honorably discharged on February 16, 1940, at the end of his term of service. The following day, he reenlisted for another three-year term. This was his sixth enlistment in the Regular Army, and his seventh including World War I. Rosters indicate that the 70th Engineer Company moved to Fort Benning, Georgia, in March 1940, but returned to Delaware in May.

On June 28, 1940, Technical Sergeant Gorman transferred to Headquarters and Service Company, 21st Engineer Regiment (Aviation) at Langley Field, Virginia. The regiment had just been reorganized on June 4, 1940, from an engineer general service regiment into the first U.S. Army Corps of Engineers unit specifically trained and equipped for airfield repair and construction. Technical Sergeant Gorman went on furlough from December 23, 1940, to January 1, 1941. Presumably, he spent the holidays with his family for the last time.

The January 1941 personnel roster, the first to list military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) codes, listed Technical Sergeant Gorman’s as 240, tire rebuilder. In that role, he would have repaired and retreaded pneumonic tires.

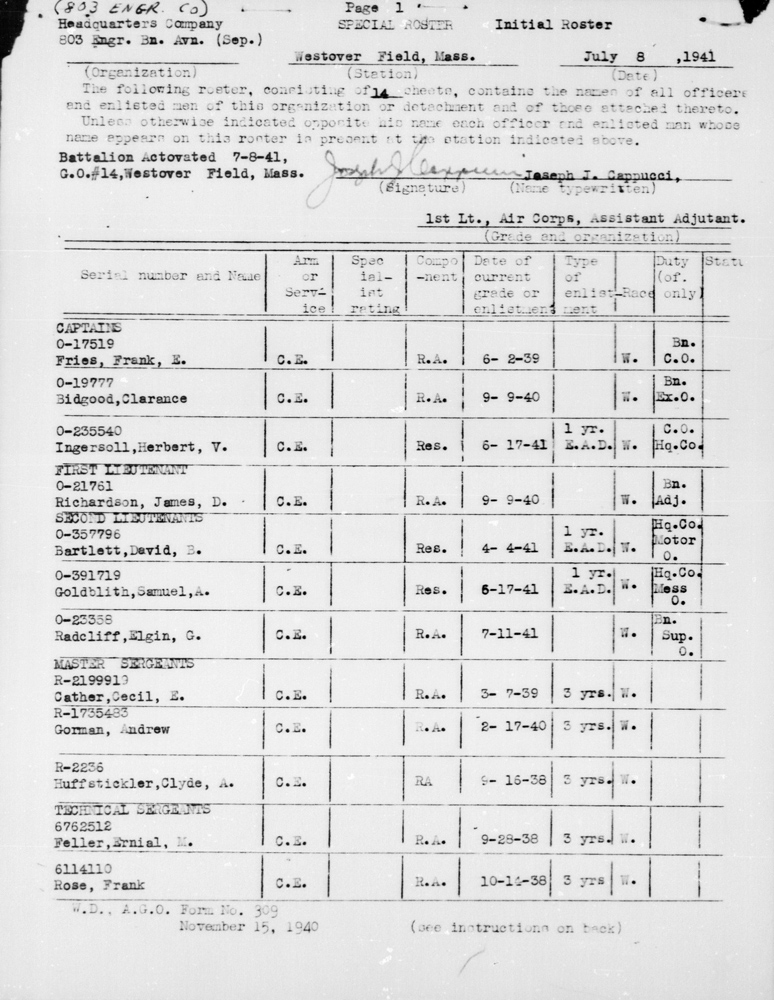

Based on the experimental 21st Engineer Regiment, the Army concluded that smaller engineer aviation battalions would be better suited for the role than regiments. On July 8, 1941, Gorman joined the cadre of the newly activated Headquarters Company, 803rd Engineer Battalion (Aviation) (Separate) at Westover Field, Massachusetts. The transfer evidently came with a promotion to master sergeant, the highest enlisted grade in the U.S. Army at the time. His M.O.S. code remained 240, tire rebuilder.

Headquarters Company was not a strictly administrative unit and performed construction work just like Companies “A” and “B.” A fourth company was incorporated into the unit as Company “C” in the Philippines.

According to Gorman’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.), Master Sergeant Gorman stood five feet, 6¾ inches tall and weighed 146 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. It is unclear when during his lengthy military career that description was recorded, but presumably it was based on medical records before he went overseas for the final time.

In September 1941, the 803rd Engineer Battalion was dispatched to the West Coast in preparation for deployment to the Philippine Islands. The situation had worsened since Master Sergeant Gorman’s last visit to the archipelago. War was looming in the Pacific and the Philippines was extremely vulnerable. American military budgets had been anemic during the aftermath of World War I and the Great Depression. With Filipino independence only a few years off, American planners had little interest in spending what limited funds remained on building up military infrastructure that was likely to be turned over to the new country in short order.

As America began rebuilding its forces after the outbreak of World War II in Europe, it belatedly increased military manpower, equipment, and infrastructure in the Philippines. In August 1941, Congress appropriated fresh funding specifically to improve or build new military airfields in the Philippines.

The Philippine Islands were at the end of long supply lines stretching across the Pacific Ocean, making it impossible to rush reinforcements in the event of a Japanese attack. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Japanese expansionism in China and southeast Asia led to increased tension with Western powers, who eventually cut off vital resources, most notably oil. For the Japanese, this presented the choice of either giving up their imperial ambitions in Asia or taking by force the resources they needed by conquering the European colonies. Weak as the Philippines’ defenses were at the time, the Japanese were unwilling to ignore the threat American forces there posed to the sea lines of communication between the Home Islands and its planned conquests to the south.

The 803rd departed by train for San Francisco, California, on September 18, 1941, with the unit’s men following three days later. An officer in the battalion, Robert D. Montgomery (1909–1983), wrote that the unit traveled in a 16-car train, all Pullman sleeping cars, via Albany, New York; Master Sergeant Gorman’s hometown of Buffalo, New York; New York City; East St. Louis, Illinois; Kansas City, Missouri; Dodge City, Kansas; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and Barstow, California, before arriving in San Francisco on September 26, 1941. The unit staged at Fort McDowell on Angel Island, California, before sailing aboard the transport U.S.A.T. Tasker H. Bliss on October 4, 1941. The men of the 803rd disembarked for a few hours in Honolulu, Hawaii, on October 9, 1941, before setting sail again early the following morning. After a brief stop at Guam on October 19, 1941, the transport continued west.

At 2100 hours on October 23, 1941, Tasker H. Bliss arrived in Manila, Luzon, Philippine Islands. It was just six weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The 803rd Engineer Battalion set up a camp at Clark Field. Expanding the base with additional runways and revetments was a top priority that was already in progress before the unit arrived. Digging trenches also became a priority after war broke out. The 803rd was hampered by the fact that its equipment had been broken up into multiple shipments that arrived over the next two months. While Master Sergeant Gorman and Headquarters Company remained at Clark Field, the rest of the companies in the battalion split off to work at other fields.

World War II

Mere hours after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor—in the Philippines, on the other side of the International Date Line from Hawaii, it was December 8, 1941—Japanese aircraft struck Clark Field, destroying much of the U.S. Far East Air Force (F.E.A.F.) on the ground. Amidst the bombing and strafing, some members of the 803rd Engineer Battalion fired machine guns and even their rifles at the marauders, to little effect.

In his book, Good Outfit: The 803rd Engineer Battalion and the Defense of the Philippines, 1941–1942, Paul W. Ropp wrote that “Immediately after the attack, Headquarters Company ceased working on runway development to focus on repairs.” He added:

Every available man in Headquarters Company worked to salvage trucks and equipment and to repair the runways. They filled the craters in the runways, some four feet deep and eight feet wide, and rolled them smooth. […] By dusk, on 8 December, the strips were again operational.

With F.E.A.F. decimated and the Cavite Navy Yard wrecked, most of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet’s surface units fled south, leaving the submarine force to oppose the inbound Japanese invasion force. Plagued by faulty torpedoes and doctrine, the force of over 20 American submarines sank only two or three ships. Japanese troops began landing on Luzon on December 10, 1941.

Ropp continued:

The repair work continued at Clark Field through eight Japanese bombing raids and one strafing attack, as well as numerous false alarms from 9 to 24 December. […]

The repair work itself reflected one of the many ways the 803rd adapted to the situation at hand. Work details deployed to airstrips in the early morning and received breakfast in the field. A work detail included a truck and driver, an air guard, and bulldozer and carry all operators.

Japanese landings at Lingayen Gulf rendered Clark Field indefensible. Christmas 1941 found the men of the 803rd destroying the field’s stores of fuel and bombs to deny them to the enemy. Headquarters Company managed to retreat with some precious supplies south to the soon to be infamous Bataan Peninsula.

They would need all they could get. Although the prewar War Plan Orange-3 called for a withdrawal to Bataan if the Japanese invaded the Philippines, few supplies had been stockpiled there. General Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964) had also delayed executing the plan until two weeks into the invasion in the vain hope that American and Filipino forces could halt the Japanese without ceding most of the archipelago. The delay meant that forces evacuating to Bataan had no choice but to abandon food and equipment that would be desperately needed in the months ahead—indeed, during the first week in January 1942, the defenders’ rations were drastically reduced to conserve what remained. Still, with Bataan and the island fortresses in Manila Bay in American-Filipino hands, the Japanese were denied use of the vital port.

As the situation on Bataan grew increasingly dire, the 803rd Engineer Battalion was stretched thin performing numerous projects. Sometimes supplemented by civilian laborers or engineers from other units, they built new roads, airfields, and gun emplacements on Bataan and repaired them after Japanese air raids. They also moved equipment, delt with unexploded ordnance, and deconstructed and moved rice and saw mills.

Diseases like malaria and dysentery rendered as many as half of the men in the battalion ineffective at any one time. The men of Headquarters Company supplemented their meager rations with carabao and monkey meat.

By February 1942, American and Filipino defenders on Bataan had fended off repeated Japanese assaults and annihilated a Japanese amphibious force during the Battle of the Points. Due to these setbacks, the Japanese temporarily ceased their offensive on Bataan. Unfortunately, this did little but delay the inevitable. Thanks to their victories in Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies, the Japanese were able to bring reinforcements to the Philippines while the Allies, already on the brink of starvation, were cut off from both resupply and evacuation.

In early April 1942, a new Japanese offensive decisively broke the American and Filipino defenses on Bataan. Facing imminent surrender, the 803rd Engineer Battalion men began destroying vehicles and equipment to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. Aside from Company “A,” which had a temporary reprieve when it was transferred to Corregidor after the Battle of the Points, the men of the 803rd Engineer Battalion, including Master Sergeant Gorman, became prisoners of war on April 9, 1942.

Journal-Every Evening reported on June 5, 1942, that Master Sergeant Gorman’s wife was notified that he was missing in action, adding that he “was last heard from in a letter dated Nov. 3 at Fort Stotsenb[u]rg, Philippine Islands, and received here Dec. 17.”

Prisoner of the Japanese

The Japanese mistreatment of their American and Filipino prisoners defies belief. The survivors of the Battle of Bataan endured a multiday forced march in the heat without adequate food or water. Japanese guards often robbed their prisoners of their few personal effects and inflicted injury or death for the most trivial of offenses, or for no reason at all. Men who collapsed were frequently bayoneted or shot. Those who made it to San Fernando were crammed aboard freight cars and moved by rail to Capas before finally marching to Camp O’Donnell.

Among the units which surrendered at Bataan, Headquarters Company of the 803rd Engineer Battalion had been relatively fortunate, suffering only two fatalities during the campaign and none during the Bataan Death March. However, conditions at Camp O’Donnell were abysmal. There was little water and inadequate sanitation facilities. Dozens of men from the 803rd died from malnutrition and disease. In mid-1942, most of the prisoners were moved to another camp at Cabanatuan, in central Luzon. Conditions were better than at Camp O’Donnell, but dozens more members of the unit succumbed there.

Conditions slowly improved. During Christmas 1942, the Japanese finally distributed packages from the Red Cross filled with food, medicine, and hygiene supplies. John C. McManus wrote in his book, Fire and Fortitude: The US Army in the Pacific War, 1941–1943, that during late 1942 and 1943:

Food consumption rose from starvation to subsistence levels. Death and disease rates declined. The average prisoner received between two thousand and twenty-six hundred calories per day. […] Meals consisted mainly of steamed rice, beans, scrawny sweet potatoes, or onions or squash, augmented with a little carabao meat, maybe an ear of corn or a tomato.

Sanitation also improved, with a septic system replacing open latrines. Some prisoners earned extra food and a small amount of money, which they could spend in the camp’s commissary, by working on the camp’s farm. The Japanese allowed the prisoners to entertain themselves by putting on plays, concerts, lectures, and playing sports. There was even a camp library. Still, many guards were quick to resort to violence for minor or imagined infractions, and attempting to escape was punishable by death.

For over a year after the fall of Bataan, Master Sergeant Gorman officially remained missing in action, until May 23, 1943, when the War Department finally received notification via the International Red Cross that he was a prisoner of war.

On August 27, 1943, Journal-Every Evening reported:

Mrs. Gertrude Gorman, 915 Gray Street, New Castle, has received a post card from her husband, Master Sergt. Andrew Gorman, a prisoner in a military prison camp in the Philippines. The message says Sergeant Gorman is well and uninjured, and requests the recipient to take care of the two boys, and he sends his love to the family best regards to all friends.

This is the first word received from Sergeant Gorman since May, 194[3], when official word of his having been taken prisoner by the Japanese was received.

Another postcard, undoubtedly written in 1944 but which Gorman’s family did not receive until September 12, 1945, had a typed message:

Received box, many thanks to you very much. Every thing is alright with me, so please don’t worry. Tell the boys that I am feeling fine. Regards to all at home and love to you and the boys, yours as ever, Husband Andrew,

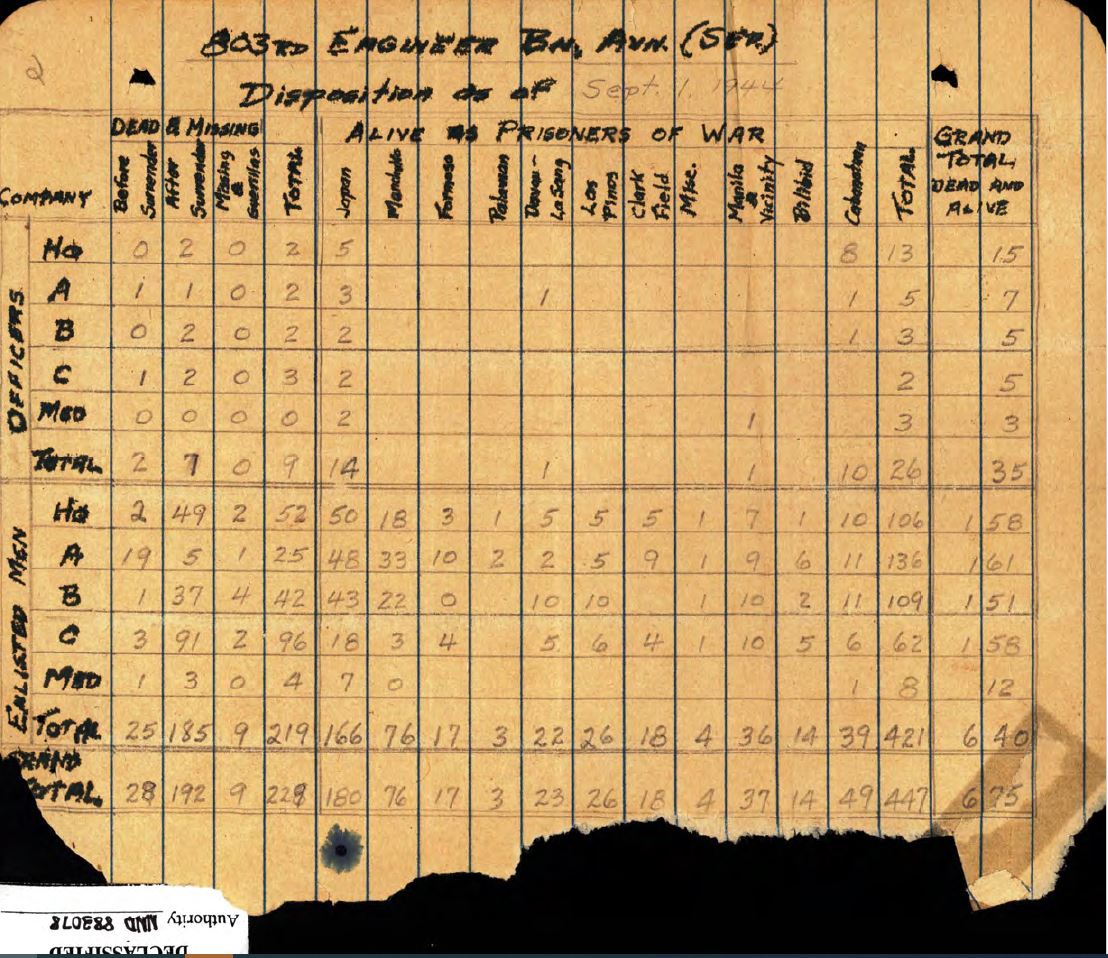

A preliminary list compiled by members of the 803rd Engineer Battalion while still prisoners stated that as of September 1, 1944, at least 220 of 675 men in the unit had already died, with another nine unaccounted for. 193 of those fatalities had occurred after surrendering to the Japanese. Headquarters Company had lost at least 53 men dead—51 of those since surrendering—and two missing, meaning about a third of the company had already died.

A letter to Gorman’s wife dated June 29, 1945, written by Althea Lotz Richardson (1919–1974), a Delawarean who was the wife of the 803rd’s Captain James Donald Richardson (1915–1989), quoted another, unidentified captain:

“Gorman was not wounded […]. He had had high blood pressure in camp and for that reason did not work very much. He was in good health, except for being underweight when he left the Philippine Islands.” (My husband was underweight also). “He did have some kind of Special duty job on the farm for awhile, but quit it when our Doctors marked him sick in quarters. He was never in the hospital at any time.” […]

“Tell Mrs. Gorman not to worry as Andy knows how to take care of himself. I have known him quite awhile and I am sure he will come thru if ther[e] is any chance at all.”

As the war turned against the Japanese, conditions in the prison camps deteriorated again. American troops began landing in the southern Philippines in mid-October 1944. Unfortunately, the Japanese began to evacuate their prisoners just as their liberation appeared imminent. The suffering that Allied prisoners endured aboard what came to be known as hell ships defies imagination.

Accurate information about the war was hard to come by in the camps and rumors had swirled for years, but the air raids by American planes that hit Manila while Gorman was waiting for transport to Japan would have left little doubt that the tide had turned.

Whatever hope the sight of American airpower gave the prisoners was fleeting. Gorman and over 1,600 other Allied prisoners were crammed into holds aboard Oryoku Maru on December 13, 1944. The ship was overloaded with prisoners and Japanese civilians. For the prisoners in the holds, the heat was unbearable. There was inadequate food and water. Sanitation, space, and ventilation were non-existent. The hell ship got underway that evening. Dozens of men died from the abysmal conditions even before U.S. Navy aircraft bombed and strafed the ship on the morning of December 14, 1944. Some Americans were killed outright in the attack, but the survivors’ ordeal was only beginning.

Oryoku Maru staggered back to Subic Bay. The Japanese began evacuating the ship’s passengers, while ordering the Americans to stay put aboard the foundering ship. Men who tried to escape the ship were ruthlessly shot. Finally, the next day, December 15, 1944, the prisoners were allowed to abandon ship, though only some of the wounded were allowed to use lifeboats. The other weary men had to swim for their lives. Another American air raid struck the ship, killing more prisoners. Even after everything else, the Japanese machine gunned some of the survivors as they struggled to shore. The ship finally sank that same day.

However, the dying did not end there. The survivors were evacuated from the Philippines aboard two more hell ships, Enoura Maru and Brazil Maru. Many hundreds more died of mistreatment and American attacks before the last survivors, numbering about 500 men, finally arrived on Kyushu on January 30, 1945.

A board of officers concluded that Master Sergeant Gorman was among those who died in the sinking of Oryoku Maru based on a list of fatalities obtained from the Japanese government.

Notwithstanding the Japanese records, unless American investigators obtained an eyewitness account of a particular individual’s death from a survivor, it was difficult to establish a soldier’s fate with certainty.

In a roster in his book, Good Outfit, compiling the fates of members of the 803rd Aviation Battalion, Paul W. Ropp raises the possibility that Gorman may have died aboard one of the hell ships after Oryoku Maru. If Gorman did survive the initial sinking of Oryoku Maru, he did not survive the subsequent journey to Japan. Still, as a senior noncommissioned officer in his unit, it is likely that survivors of the 803rd would have noticed Gorman had he survived the sinking of Oryoku Maru, and that one or more witnesses would have reported it to authorities or to Gorman’s family after the war. That suggests that the Japanese records placing Gorman as one of the Oryoku Maru victims is credible.

The War Department changed Master Sergeant Gorman’s status to killed in action on July 23, 1945, with his official date of death being December 15, 1944. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

In 1948, a board of officers deemed Gorman’s remains to be unrecoverable. He is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery. Although his name appeared on the official 1946 U.S. Army casualty list for Delaware, Master Sergeant Gorman’s name was omitted from Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle. The reason for his omission may have been related to the fact that he originally entered the service from New York. Eventually, during a Memorial Day ceremony on May 30, 1997, with Master Sergeant Gorman’s two youngest sons looking on, Senator Joe Biden added Gorman’s name to the wall at Veterans Memorial Park.

Notes

Name

Some records give Gorman’s name as Andrew L. Gorman. However, it appears he served in the U.S. Army with no middle initial. All known surviving military records refer to him as Andrew Gorman except one muster roll from 1918 which refers to him as Andrew Louis Gorman. Some family trees and his Find a Grave entries also refer to him by that name.

Father

Theodore Gorman’s year of birth is wildly inconsistent in existing records, listing ages that suggested years of birth between 1839 and 1855.

Date of Birth

The 1900 census stated that Gorman had been born in April 1897. His World War I draft card and individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) listed his date of birth as April 16, 1896.

Service Number

Gorman’s original service number was 1735483. U.S. Army personnel from the World War I era National Army who later reenlisted had an R- prefix added, making his service number R-1735483. Soldiers with this prefix were rare by World War II.

Second Marriage

Records are incomplete and contradictory about when Gorman married his second wife. The earliest known record is a March 9, 1929, article in The Evening Journal that mentioned “Robert Gorman, two-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Gorman is confined to his bed by illness.” On the other hand, newspaper articles as late as 1934 as well as the 1940 census refer to his wife and children’s last names as Ingram.

Personnel File

Some of Gorman’s personnel records were undoubtedly lost in the fall of the Philippines and those documents that survived the catastrophe were largely destroyed in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire. Archives staff compiled an R-file (reconstructed file) which includes a World War I hospital record and several payroll records from the end of some of his enlistments. I was able to largely reconstruct his career mainly from morning reports and rosters.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Gorman family for photos and documents, and to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research and to Wes Injerd and John Hicks for documents and information.

Bibliography

“803rd Engineer Bn. Avn. (Sep.) Disposition as of Sept. 1, 1944.” September 1, 1944. Rosters and Lists of Prisoners of War (POWs), 1942–1947. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Courtesy of Wes Injerd.

Abstract of World War I Military Service for Andrew Gorman. New York State Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919. New York State Archives, Albany, New York. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/3030/images/40808_1120704930_0245-00715

Census Record for Andrew Gorman. January 6–7, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RX4-9SF

Census Record for Andrew Gorman. April 9, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-MYJ

Census Record for Andrew Gormann. June 7–8, 1900. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6X43-8SG

Census Record for Andrew Gormann, Jr. April 15, 1910. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRJY-6F1

Census Record for Andrew L. German. April 4, 1940. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRHM-75G

Census Record for Andrew L. Gorman. June 1, 1905. New York State Census, 1905. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6LVW-9FZ

Census Record for Gertrude V. Ingram. April 5, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-M9SM

Census Record for Theodore Gormann. April 15, 1910. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRJY-6XD

Certificate of Birth for Robert Charles Ingram. Undated, c. September 13, 1927. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQM-Q4RV

Certificate of Death for Clarence G. Ingram. Undated, c. July 9, 1936. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMD-ZPDP

Certificate of Marriage for Clarence G. Engran and Gertrude V. Shilling. Undated, c. September 20, 1915. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS7K-R97G-3

“Deaths.” Buffalo Courier-Express, October 11, 1936. https://www.newspapers.com/article/179096280/

“Died.” The Buffalo Enquirer, May 17, 1924. https://www.newspapers.com/article/155775219/

“Directs Findings For Mrs. Gorman.” The Buffalo Evening Times, December 20, 1922. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154626495/

Draft Registration Card for Andrew Gorman. June 5, 1917. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-L165-9965

Draft Registration Card for Robert Andrew Gorman. September 4, 1945. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-X9F3-Q

“Eight of the First Sixteen Buffalo Boys Drafted Who Are Hale and Hearty After Serving Through War.” Buffalo Evening Times, December 9, 1918. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154625452/

Enlistment Record for Andrew Gorman. February 17, 1940. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=01735483&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=145855

“Final Roster Company ‘C’, 1st Engineers.” October 11, 1939. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-2BQ8

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Andrew Gorman. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Individual records of discharged men.” April 5, 1919. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DN-Y9DK-W

“Initial Monthly Roster 70th Engrs. Light Ponton Co.” October 12, 1939. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZG-7915-X

“Initial Roster Headquarters Company 803 Engr. Bn. Avn. (Sep.)” July 8, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0933/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0933_08.pdf

“Initial Muster Roll of Company ‘F’ of the 309th Infantry Army of the United States, from dates of enlistment to muster on the 31st day of October, 1917. October 31, 1917. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HT-7SGX-P

“Joseph H. Gorman, Sr.” The News Journal, September 3, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154637153/

La Forte, Robert S., Marcello, Ronald E., and Himmel, Richard L., eds. With Only the Will to Live: Accounts of Americans in Japanese Prison Camps 1941–1945. Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1994.

Leggett, James L. Jr. “Records of 803d Engineer Battalion (Avn) (Sep).” September 26, 1945. Rosters and Lists of Prisoners of War (POWs), 1942–1947. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Courtesy of Wes Injerd.

“LTC James Donald Richardson.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/15867658/james-donald-richardson

“Marine Corps Commissions Thos. Holcomb.” Journal-Every Evening, June 5, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154563316/

“Marriage Licenses.” Buffalo Evening News, October 29, 1919. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154564854/

McManus, John C. Fire and Fortitude: The US Army in the Pacific War, 1941–1943. Dutton Caliber, 2019.

Milford, Phil. “Honoring fallen comrades.” The News Journal, May 31, 1997. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-news-journal-andrew-l-gorman-added/87657576/

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jan 31 1941 HQ–Service Co 21st Engineers.” January 31, 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705_03.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jul 31 1941 HQ–HQ Company 803rd Engrs Bn.” July 31, 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0933/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0933_09.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jun 30 1941 HQ–Service Co 21st Engineers.” June 30, 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705_03.pdf

“Monthly Roster 70th Engr Co (Light Ponton).” February 29, 1940. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1000/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1000_01.pdf

“Monthly Roster 70th Engr Co (Light Ponton).” June 30, 1940. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1000/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1000_01.pdf

“Monthly Roster 70th Engr Co (Light Ponton).” October 31, 1939. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZG-79RH-G

“Monthly Roster Co ‘D’ 1st Combat Engr Regt.” May 31, 1928. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-2BHM

“Monthly Roster Co ‘F’ 1st Combat Engr Regt.” July 31, 1926. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-2TBT

“Monthly Roster Co ‘F’ 1st Engr Combat Regt.” April 30, 1926. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-299G-6

“Monthly Roster Co. ‘K’ 19th Regiment, T.C.” September 30, 1918. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-63CZ-NLLL

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” April 30, 1937. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-2YXL

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” December 31, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-22G8

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” February 28, 1937. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-2RJ1

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” January 31, 1935. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-2BVQ

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” July 31, 1936. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-21F2

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” June 30, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-2B2T

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” June 30, 1936. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-29ML-2

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” March 31, 1937. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-2T58

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” May 31, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-2G9Q

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” October 31, 1936. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-21CF

“Monthly Roster Company ‘C’ 1st Engineers.” November 30, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-2RWS

“Monthly Roster Company ‘D’ First Engineers.” February 28, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-2RVD

“Monthly Roster Company ‘D’ First Engineers.” June 30, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-2YHZ

“Monthly Roster Company ‘D’ First Engineers.” May 31, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-2RP2

“Monthly Roster Company ‘F’ 1st Engineers.” February 28, 1925. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-25Y6

“Monthly Roster Department Engineer Detachment, HPD, Fort Santiago, P.I.” March 31, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3C6-5946-9

“Monthly Roster Department Engineer Detachment, HPD, Fort Santiago, P.I.” May 31, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3C6-59N5-K

“Monthly Roster Department Engineer Detachment, HPD, Ft. Santiago, P.I.” August 31, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3C6-59FN-Z

“Monthly Roster Department Engineer Detachment, HPD, Ft Santiago, P.I.” February 28, 1934. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-X3C6-594G-D

“Monthly Roster Department Engineer Detachment, HPD, Ft. Santiago, P.I.” July 31, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3C6-59FG-T

“Monthly Roster Department Engineer Detachment, HPD, Ft. Santiago, P.I.” June 30, 1931. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-X3C6-59ZH-T

“Monthly Roster Hq. and Serv. Co., 21st Engrs. (AVN).” June 30, 1940. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705_02.pdf

“Monthly Roster H&S Company 21st Engrs. (AVN).” December 31, 1940. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0705_03.pdf

“Monthly Roster of ‘K’ of 19th Regiment Transp. Corps.” October 31, 1918. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-D3CZ-NVJJ

Morning Reports for 70th Engineer Company (Light Ponton). November 1939. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.fold3.com/image/711042356/nov-1939-page-8-us-morning-reports-1912-1939

Morning Reports for Company “D,” 1st Engineers. February 1931. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.fold3.com/image/710924223/feb-1931-page-4-us-morning-reports-1912-1939

Morning Reports for Company “D,” 1st Engineers. April 1931. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.fold3.com/image/710924242/apr-1931-page-5-us-morning-reports-1912-1939

“Muster Roll of Company ‘F’ of the 309th Infantry Army of the United States, from last bimonthly muster on the 31st day of December, 1917, to muster on the 28th day of February, 1918.” February 28, 1918. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HT-7SGY-6

“Muster Roll of Company ‘F’ of the 309th Infantry Army of the United States, from last bimonthly muster on the 31st day of October, 1917, to muster on the 31st day of December, 1917.” December 31, 1917. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3HT-7S1W-3

“Muster Roll of Co. K, 19th Engrs. (Ry) Army of the United States from last bimonthly muster on the 30th day of April, 1918, to muster on the 30th day of June, 1918.” June 30, 1918. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZJ-LXD1

“Muster Roll of Detachment of the Det. 1st. Prov. Bn. S. O. U. Army of the United States, Formed Apr. 27th, 1918, to muster on the 30th day of April, 1918.” April 30, 1918. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-D3CZ-JC4F

New York State Marriage Index, 1919. New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61632/images/48576_556171-00566

Official Military Personnel File for Andrew Gorman. Official Military Personnel Files, 1912–1998. Record Group 319, Records of the Army Staff. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

“Our Men and Women In Service.” Journal-Every Evening, August 27, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154563036/

“Passenger List of Organizations, 81st Co 19th Co Transportation Corps.” March 3, 1919. Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917–1938. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61174/images/44508_162028006074_0038-00366

“Passenger List of Organizations and Casuals, 19th Engineers, Camp Dix Reinforcement Detachment.” March 29, 1918. Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917–1938. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61174/images/44509_3421606189_0289-00780

“Passenger List United States Transport ‘U. S. Grant’.” May 5, 1931. Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917–1938. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61174/images/44509_162028006074_0269-00461, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61174/images/44509_162028006074_0269-00618

Pearson, Judith L. Belly of the Beast: A POW’s Inspiring True Story of Faith, Courage, and Survival Aboard the Infamous WWII Japanese Hell Ship Oryoku Maru. Diversion Books, 2001.

Richardson, Althea L. Letter to Gertrude Gorman. June 29, 1945. Courtesy of the Gorman family.

“Robert A. Gorman.” The News Journal, November 22, 1999. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154635549/

Ropp, Paul W. Good Outfit: The 803rd Engineer Battalion and the Defense of the Philippines, 1941–1942. Air University Press, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-D301-PURL-gpo193871/pdf/GOVPUB-D301-PURL-gpo193871.pdf

“Roster of Officers 803d Engr. Bn. (Avn.) (Sep.).” October 15, 1942. Rosters and Lists of Prisoners of War (POWs), 1942–1947. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Courtesy of Wes Injerd.

“Roster of Troops Headquarters Company.” October 15, 1942. Rosters and Lists of Prisoners of War (POWs), 1942–1947. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Courtesy of Wes Injerd.

“Special Roster Company ‘D’ First Engineers.” December 9, 1929. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZJ-2BLV

“Theodore L. Gormann.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/210093516/theodore-l-gormann

“Violet Smith Jodd.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/89124425/violet-jodd

Last updated on August 19, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.

Nice job on the research.

LikeLike