| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Photostat operator and tack welder |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Naval Reserve | 8262014 |

| Theater | Vessel |

| Pacific | U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Normandy, Leyte, Luzon, Iwo Jima, Okinawa |

Early Life & Family

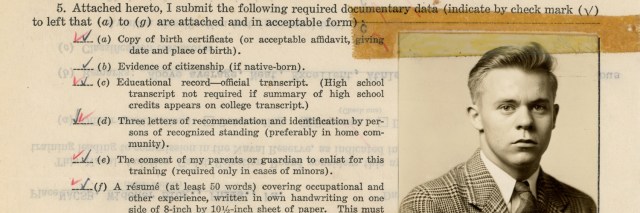

Robert Curtis Miller was born in the Delaware Hospital in Wilmington, Delaware, on May 4, 1924. He was the child of Charles Broadhart Miller (a brakeman for the Reading Railroad, 1900–1970) and Rose Miller (née Nero, 1903–2001). His delayed birth certificate, filled out in 1939, stated that his parents were living at 312 South Van Buren Street at the time of his birth. He had an older brother and two younger sisters.

The Millers were recorded on the census in April 1930 living at 211 South Van Buren Street. By April 1940, they had moved to 1201 Read Street.

Miller reported that he played basketball, football, and baseball at Wilmington High School and was vice president of his high school class. Documentation in his personnel file is inconsistent about whether he completed three years of high school or was a high school graduate. However, Journal-Every Evening reported that Miller “was graduated from Wilmington High School and had been employed by the Benjamin F. Shaw Company before entering the Navy.”

Miller told the Navy that he worked for about six months as a photostat operator for the DuPont Company in Wilmington, Delaware, until September 1, 1942, earning $100 per month. He also advised that he had five months of experience as a tack welder for a pipe bending and pipe fitting business, earning about $178 per month.

According to his Navy personnel file, Walker stood five feet, nine inches tall and weighed 142 lbs., with brown hair (though his identification card said he was blonde) and blue eyes. He was Baptist.

Training & Service in the Atlantic

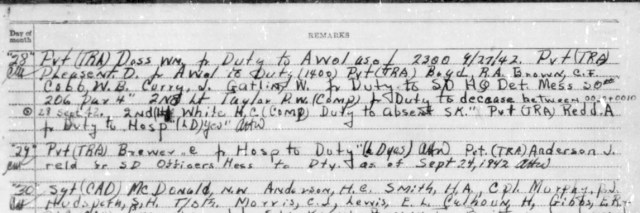

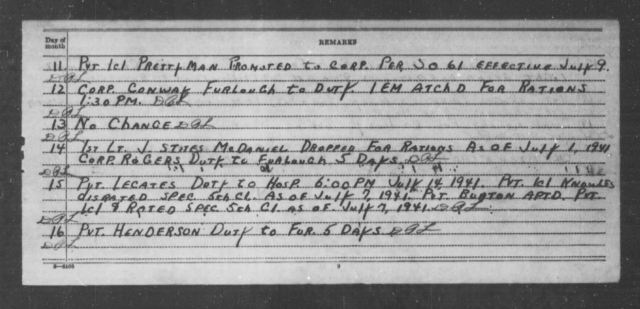

After he was drafted, Miller requested naval service, making him what the U.S. Navy referred to as a “selective volunteer.” Miller joined the U.S. Naval Reserve in Wilmington, Delaware, on January 14, 1943. That same day, he was dispatched the U.S. Naval Training Station, Newport, Rhode Island, for boot camp. He was hospitalized during March 17–23, 1943, and was promoted to seaman 2nd class on April 5, 1943. On April 15, he was transferred to the U.S. Navy Armed Guard Center, Brooklyn, New York. The U.S. Navy Armed Guard manned guns aboard American and friendly merchant ships.

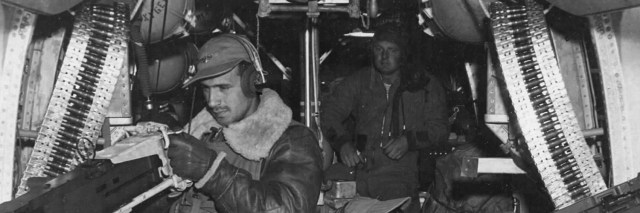

Miller was promoted to seaman 1st class on April 26, 1943, the day he was placed on detached duty aboard the S.S. Bridgeport, which plied coastal waters between New York and the Caribbean Sea. He served as a 20 mm gunner and as a 5-inch gun powderman. Miller completed his assignment aboard Bridgeport on August 24, 1943. The following day, he went on detached duty serving as loader for a 3-inch gun aboard S.S. Paul H. Harwood, a Standard Oil of New Jersey tanker chartered by the War Shipping Administration.

Carrying a load of 80 octane gasoline, Harwood departed New York City along with Convoy HX-254 on the morning of August 27, 1943. It appears that Harwood separated from the rest of the convoy as she neared the British Isles. While the main body of the convoy continued to Liverpool, England, Harwood arrived in Loch Ewe, in western Scotland, on the evening of September 10, 1943. The following day, she joined another convoy traveling to eastern Scotland, arriving at Methil on September 13. On September 15, she joined a southbound convoy, arriving at the mouth of the Thames the following day.

Harwood docked in London shortly after noon on September 17, 1943. After unloading her cargo, she sailed from London on September 19, retracing her previous route to Loch Ewe via Methil. She arrived at Loch Ewe shortly after midnight on September 23, 1943. On September 18, 1943, Harwood departed Loch Ewe, meeting westbound Convoy ON-204 at sea the following morning.

A report by Miller’s Naval Armed Guard commanding officer stated that Harwood detached from the convoy on October 14, 1943, with orders to proceed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The report stated that around October 15, 1943, Harwood docked at Paulsboro, New Jersey, on the other side of the Delaware River from Philadelphia, and that the following day, Miller and 14 other members of the Navy Armed Guard complement were transferred back to Brooklyn.

During his last voyage aboard Harwood, on October 12, 1943, Miller was accused of improperly standing watch. He was demoted to seaman 2nd class on November 3, 1943. After Miller was convicted by deck court martial on November 9, 1943, he was sentenced to 20 days’ confinement, though he was released before that full sentence was carried out. He also forfeited $18 of his pay for two months, a total fine of $36. A note in his personnel file stated that Miller “Had Cox papers in, but broken in deck court” suggesting that he had intended to strike for the rating of coxswain, but that the discipline he received had foreclosed that avenue for advancement.

Seaman 2nd Class Miller transferred to the Receiving Station, Norfolk, Virginia, on November 22, 1943, arriving the following day. At the Naval Training Station, Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, Virginia, attended destroyer training. Miller would get a fresh start as one of the “tin can sailors.” He joined the crew of the new destroyer U.S.S. Laffey (DD-724) on February 8, 1944, the day she was commissioned at the Boston Navy Yard, Massachusetts. Laffey and many of her sister Allen M. Sumner-class destroyers were named after American destroyers lost in battle earlier in the war. Those losses had been heavy. Destroyers were fast, but small and unarmored. In the ruthless calculus of naval warfare, an admiral would not hesitate to sacrifice destroyers to preserve larger and more valuable ships like aircraft carriers.

On February 27, after a few weeks fitting out, Laffey set sail for Washington, D.C., arriving the following day. Following bridge modifications there, she sailed for Bermuda on March 2, 1944. The ship arrived there on March 4. After a two-day quarantine, Laffey spent the rest of the month undergoing “routine shakedown exercises” except on March 10, 1944, when she was dispatched to pick up survivors of a downed Consolidated PBY-5A Catalina flying boat. Laffey’s crew successfully picked up 19 survivors.

Her shakedown cruise complete, Laffey sailed for Boston on March 31, 1944, arriving two days later. The ship spent much of the month of April in drydock for the installation of additional equipment. During that time, Miller went on leave or liberty, for which he was due back at 0700 hours on April 17, 1944. He did not return to his ship until 0940. Although Miller was subjected to a captain’s mast, his commander let him off with a warning.

Departing Boston on May 5, 1944, Laffey spent the next week shuffling between ports, visiting Norfolk, followed by New London, Connecticut, and finally New York City. She departed New York on May 14, 1944, performing escort duty for a transatlantic convoy until Laffey and the rest of Destroyer Division 119 were detached on May 24. After a brief stop for fuel at Greenock, Scotland, Laffey and DesDiv 119 escorted a convoy to Portland, England. They arrived at Plymouth, England, on May 27, 1944. With the invasion of Normandy just over a week away, ports in southern England were abuzz with activity.

On June 3, 1944, Laffey departed Plymouth to escort a convoy to Utah Beach. The convoy was recalled the following day after D-Day was postponed due to bad weather. No sooner did the last ships make it into Weymouth early on June 5, 1944, than it was time to head back to France. Laffey arrived at Baie de la Seine off Normandy on the morning of D-Day: June 6, 1944. With the Germans unable to seriously challenge the landings by sea or air, the first two days of the invasion proved uneventful for Laffey and her crew.

On the evening of June 7, 1944, Laffey was placed on fire support duty for the troops ashore. During the next two days, the destroyer shelled German pillboxes, artillery emplacements, and troop concentrations under the direction of a shore fire control party. On June 9, Laffey briefly came under fire from German shore batteries but was not hit. The destroyer was relieved of fire support duty that afternoon and the following morning was ordered back to Plymouth to refuel and rearm.

Laffey returned to the waters off Normandy on June 11, 1944, to continue screening duty. Shortly after midnight on June 12, 1944, Laffey gave chase to German E-boats that had torpedoed the destroyer U.S.S. Nelson (DD-623), opening fire with inconclusive results. The next 10 days were generally uneventful, and Laffey returned to Portland on June 22, 1944. She briefly departed on June 24 for the Cherbourg area before being recalled to Weymouth Roads.

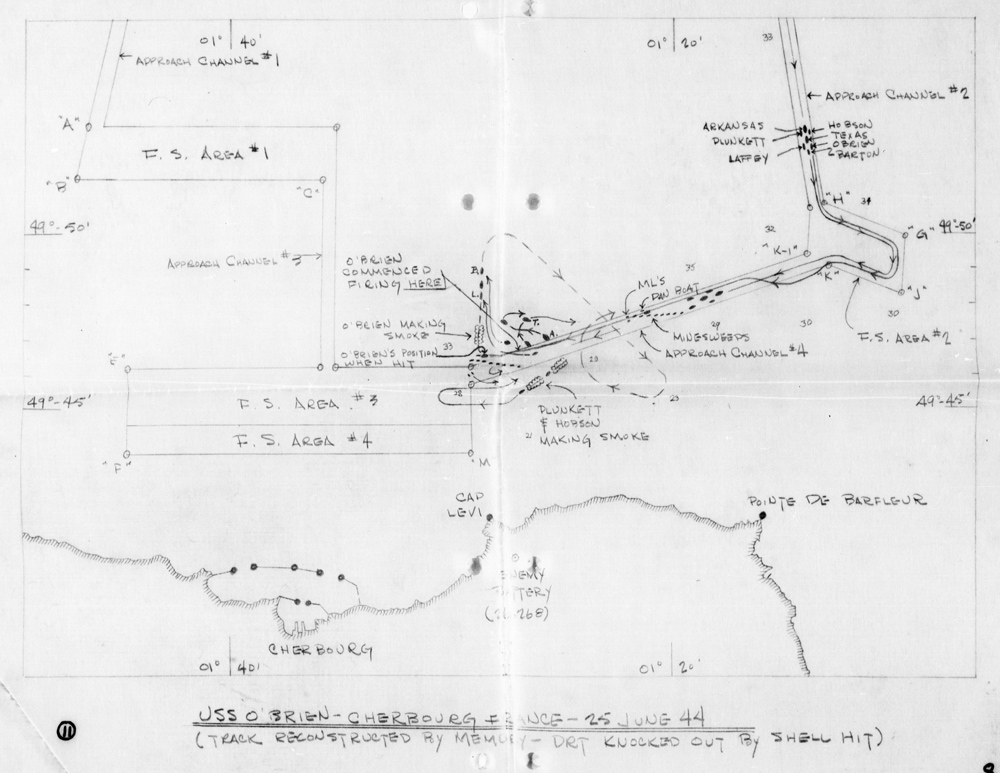

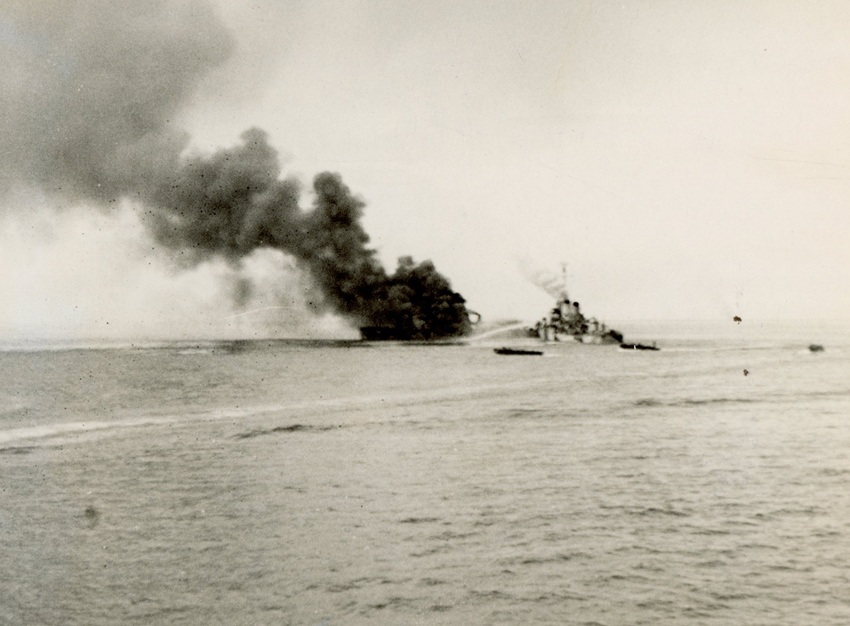

For Laffey’s crew, the climax of the Normandy campaign may have been June 25, 1944, when she sallied with Bombardment Group Two, one of five destroyers escorting the battleships U.S.S. Texas (BB-35) and U.S.S. Arkansas (BB-33) during their famous duel with German shore batteries near Cherbourg, a vital port under siege by Allied forces. Well protected in reinforced-concrete casemates, the heaviest enemy batteries sported 280 mm guns, more powerful than those mounted on heavy cruisers.

Laffey’s war diary stated that

the group proceeded toward Fire Support Area Three in company with mine sweepers. BARTON, LAFFEY and O’BRIEN were in swept channel to northward of mine sweepers when, at 1230, a salvo of shells struck the water ahead of this ship, one hitting BARTON. Maneuvered at various speeds in the channel and north of it to avoid the fire while trying to locate position of the shore battery. At 1232 another salvo of shells struck the water ahead of this ship, one close to the port bow ricocheting into the side of the ship above the waterline just forward of the anchor; fortunately, this shell did not explode. Due to fog and smoke over the land, could not see flashes from enemy guns. Made smoke and cleared the immediate area at high speed and sustained no further damage.

Although Laffey and Barton sustained no major damage, their sister ship, U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725), was not so lucky. Her action report stated that O’Brien took a single hit from a large caliber shell “in the after upper starboard corner of the bridge superstructure putting all radars and Combat Information Center out of commission.” The destroyer sustained 32 casualties, 13 of them fatal, and limped back to Portland.

Three days after the tragedy, on June 28, 1944, Miller and two other men transferred from Laffey to O’Brien. Although it was only supposed to be a temporary duty assignment, Miller remained with O’Brien for the remainder of his career. The service aboard his new ship would demonstrate that Miller had matured as a sailor. His personnel file showed no further disciplinary infractions and his service aboard O’Brien would provide him with the opportunity to become a petty officer. His file noted that Miller was a “SM striker on bridge gang” indicating that he trained at sea to become a signalman, though the document was ambiguously worded about whether he started the process aboard Laffey or O’Brien.

Following temporary repairs, O’Brien departed England on June 29, 1944, arriving the following day in Belfast, Northern Ireland. On July 3, 1944, she sailed for Boston, Massachusetts, arriving six days later. The destroyer spent over a month undergoing repairs and alterations. Miller returned home for the final time on leave during July 20–30, 1944.

After the completion of repairs, O’Brien returned to service on August 20, 1944, and spent the next few days training in the waters off New England and Virginia. On August 30, 1944, she departed Norfolk, joining the destroyers U.S.S. Maddox (DD-731) and U.S.S. Walke (DD-723) in escorting the new carrier U.S.S. Ticonderoga (CV-14) to join the Pacific Fleet. (Coincidentally, 20 years later both Maddox and Ticonderoga would be involved in the Gulf of Tonkin incident off the coast of Vietnam.)

Service in the Pacific Theater

Miller was promoted back to seaman 1st class on September 1, 1944. On September 3, 1944, O’Brien transited the Panama Canal and moored at Balboa, Canal Zone. Two days later, the small flotilla sailed northwest, arriving at San Diego, California, on September 13, 1944.

On September 18, 1944, O’Brien sailed from San Diego to join Maddox in escorting Ticonderoga to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, arriving on September 24. O’Brien remained assigned to the Pacific Fleet for the duration of the war. On October 1, 1944, Miller was promoted to signalman 3rd class. After a few weeks of training in Hawaiian waters, O’Brien departed Pearl Harbor on October 24, 1944, escorting the carrier U.S.S. Yorktown (CV-10). They arrived on October 31 at (Enewetak), Marshall Islands. The following day, the task unit continued west, arriving at Ulithi, Caroline Islands (present day Federated States of Micronesia), on November 3.

On November 5, 1944, O’Brien sailed for the Philippine Islands, screening a group of three carriers. Although she was too late for the climatic series of naval engagements known as the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the land battle for Leyte, not to mention the overall campaign to retake the Philippines, was still in progress. O’Brien escorted the carriers while they launched air strikes against Japanese installations in the Philippines. Despite constant vigilance, there was no sign of enemy submarines and only occasional minor raids by Japanese land-based aircraft. O’Brien returned to Ulithi on November 22.

On November 27, 1944, O’Brien departed Ulithi with Destroyer Squadron 60, arriving at Leyte Gulf on November 29. On December 7, 1944, O’Brien was dispatched to support an amphibious operation at Ormoc Bay on Leyte. In a preview of the kind of horrors that would characterize the remainder of the Pacific War, Japanese suicide planes pounced on the American destroyers. In theory, kamikaze pilots had orders to attack valuable targets like American capital ships. In practice, however, they often attacked the first Allied vessel they encountered. This time, O’Brien managed to avoid damage and poured antiaircraft fire into the attacking planes, but kamikazes stuck inflicted mortal damage to the high-speed transport U.S.S. Ward (APD-16) and destroyer U.S.S. Mahan (DD-364).

O’Brien quickly responded to Ward’s aid, rescuing her survivors and attempting in vain to bring her fires under control. O’Brien’s commanding officer, William Woodward Outerbridge (1906–1986), had been in command of Ward three years earlier when the vessel—at that time an old destroyer prior to her conversion to transport—fired the opening shots of the Pacific War, sinking a Japanese midget submarine at Pearl Harbor shortly before the airstrike began. Now, he complied with orders to sink his old ship. Kamikazes returned and damaged U.S.S. Lamson (DD-367).

O’Brien continued to operate around the Philippines. She was escorting U.S.S. Nashville (CL-43) to Mindoro, Philippine Islands, when the light cruiser was severely damaged by another kamikaze on December 13, 1944. Two days later, O’Brien found herself in another brawl between American ships and Japanese aircraft off Mindoro. Once again, she rescued survivors from another kamikaze victim, U.S.S. LST-472. She returned to Leyte on December 17. Miller and his shipmates sailed again on December 26, patrolling the Mindoro Strait until returning to Leyte on December 29.

On January 2, 1945, O’Brien sailed north again, escorting heavy ships for the landings at Lingayen Gulf on Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines. By now the Japanese response was familiar. There was no sign of enemy ships, but the enemy planes that appeared were largely suicide planes. Around 1428 hours on January 6, 1945, a Japanese fighter suddenly appeared out of an overcast sky diving straight at the ship. The ship’s war diary noted: “Plane crashed the port side of the fantail before any guns could be brought to bear.” The kamikaze’s impact flooded a compartment and damaged her depth charge racks but inflicted no casualties. The damage was not severe enough to knock the destroyer out of the fight, and she continued screening heavy ships while they conducted preinvasion shore bombardment. As the landings began on January 9, 1945, O’Brien bombarded Blue and White Beaches. The following day, she departed to escort a convoy back to Leyte, arriving on January 13.

On January 14, 1945, O’Brien sailed for Manus in the Admiralty Islands with a small task group. Three days later, on January 17, 1945, Signalman 3rd Class Miller crossed the equator for the first time and participated in a line crossing ceremony. The following day, the group arrived at Seeadler Harbor, Manus. The destroyer was drydocked for repairs from the kamikaze damage from January 20, 1945, through February 1. That day, she moved to the Repair Base Dock, Lombrum Point, on the nearby island of Los Negros. On February 6, 1945, with her battle damage repaired, O’Brien sailed for Ulithi, arriving two days later and rejoining Destroyer Squadron 60. On February 10, 1945, she sailed with Task Force 58 for a raid on the Japanese home islands. As usual, she screened heavier ships, providing antiaircraft protection for the fleet when enemy aircraft attacked. After launching airstrikes on the home islands, the force shifted to targets in the Bonin Islands as the invasion of Iwo Jima got underway. They returned to Ulithi on March 1, 1945.

Battle of Okinawa

The first three weeks of March 1945 were quiet for O’Brien’s crew. The ship had some repair work done, followed by training and radar picket duty. On March 21, 1945, O’Brien departed Ulithi with Task Force 54, Gunfire and Covering Force for the upcoming invasion of Okinawa. The two days passed uneventfully, with the fleet arriving off the Ryukyu Islands on March 25.

On March 26, 1945, O’Brien’s crew went to General Quarters three times due to aircraft in the area, but no attacks materialized. 2000 hours that evening found O’Brien sailing off the Kerama Islands, about four nautical miles southeast of Tokashiki Island and 14 nautical miles southwest of Naha, Okinawa.

In the early morning hours of March 27, 1945, alerts went out at 0155 hours and 0324 hours due to unidentified aircraft but again, the aircraft, whether Japanese or not, did not attack. At 0545, O’Brien was dispatched to Fire Support Unit No. 3 and steamed north of the Kerama Islands.

After four months of dodging suicide attacks and repeated aircraft alerts during the past day, Signalman 3rd Class Miller and the rest of O’Brien’s crew must have been on edge. They went to General Quarters again at 0618 hours due to a report of enemy aircraft in the vicinity. O’Brien’s action report stated that five minutes later, at 0623:

From a group of eleven planes almost overhead, eight of which were identified as friendly, one enemy fighter plane was sighted diving on this ship. All 20MM and 40MM guns which could bear opened fire. Plane was hit directly by many 20MM and 40MM shells at a distance of about 300 yards, burst into flames, and crashed about 75 yards on the starboard beam.

As the destroyer’s gunners focused on bringing down the first plane, O’Brien was already being targeted by another kamikaze, identified as an Aichi D3A1 Type 99 dive bomber, referred to by the Allies as the Val. The report continued that at 0624 hours, “Another enemy plane was sighted well in a dive on the ship. Ship was maneuvered radically in an attempt to bring the forward battery to bear, and all available guns opened fire.”

The destroyer’s most powerful weapons, the 5-inch dual-purpose guns which fired antiaircraft shells equipped with proximity fuzes, could not be brought to bear in time. The report continued:

Although hit many times by 20MM and 40MM shells, the plane continued to dive and crashed into the ship forward of midships on the port side, passing through the superstructure deck to the starboard side. […] The plane is believed to have carried a 500 pound bomb which exploded on the starboard side just aft of the bridge structure.

Signalman 3rd Class Miller was killed instantly. The survivors leapt into action fighting fires and treating the wounded. At 0650, with “Fires now under control, it was decided to proceed at maximum speed to the transport area in order to effect transfer of the large number of critically and seriously wounded personnel.” Casualties were 28 men killed in action or died of wounds, 22 missing, 32 seriously wounded, and 44 lightly wounded.

Miller was identified by his shipmates. At 1645 hours that afternoon, “services for men killed in action were held.” Miller and the other fatalities were buried at sea. Remarkably, with emergency repairs at sea, O’Brien was able to remain on station off Okinawa for another four days until ordered back to Ulithi on March 31, 1945.

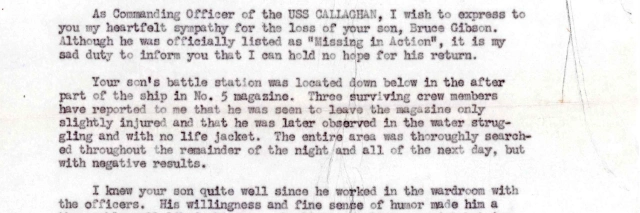

The battered destroyer reached Ulithi on April 4, 1945. In a condolence letter to Miller’s parents dated April 7, 1945, Commander Outerbridge wrote:

As shipmates aboard a small ship we knew him in a relationship that may only be compared to that of a large family, and so our loss, while not so great as yours, is none the less true and sincere.

Bob, as he was known to all on board, came to us shortly after a tragedy of a similar nature at Cherbourg, France. During that time he had gained a high place in our minds as one who was dependable and always in high spirit. His unfailing assistance to those on the “signal bridge” will be long remembered and sorely missed. His devotion to duty and loyalty was a trait much desired by all.

O’Brien soon headed back to Mare Island, California, for repairs. Miller’s previous ship, Laffey, was also damaged during the Battle of Okinawa when, on April 16, 1945, she narrowly survived six direct hits from kamikazes plus multiple bombs.

Signalman 3rd Class Miller was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. Journal-Every Evening reported on May 7, 1945, that a memorial service for Miller at Delaware Avenue-Bethany Baptist Church

was held in the afternoon and conducted by [Reverand John M.] Ballbach. A history and tribute was read by Thorpe Martin, Sr., his former Sunday school teacher. Special music was sung by Miss Mildred Miller, and played by Miss Ida Reynolds, organist.

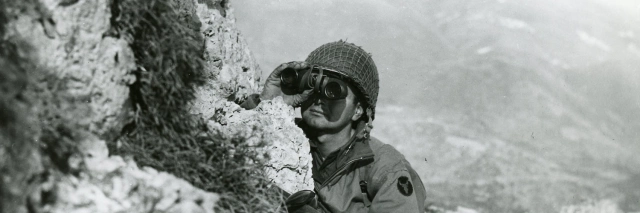

Miller’s older brother, Charles Broadhart Miller, Jr. (1922–2015), served in the U.S. Army Air Forces in the Mediterranean Theater. After the war, he worked for the DuPont Company. His obituary stated:

Charlie’s career was highlighted by his development of a new lubricant that was able to withstand the extremely high temperatures of heavy duty machinery. This product had worldwide usages and cause[d] him to travel annually to Europe and Japan. During his many visits to Japan he cultivated a true love and respect for the Japanese culture and art that persisted throughout the remainder of his life.

Signalman 3rd Class Miller is honored at the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii, at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware, and on a cenotaph at Gracelawn Memorial Park in New Castle, where his parents and sisters were buried after their deaths.

Notes

Cousin

Miller’s cousin, Aviation Ordnanceman 3rd Class James C. Walker (1924–1943), also served in the U.S. Naval Reserve during World War II and was killed in the line of duty in transit to the Pacific Theater.

Bibliography

Becton, F. J. “Operations in Assault Area, ‘Utah’ Beach, off Coast of France, Baie de la Seine Area between June 6, 1944 and June 21, 1944 — Report of.” June 30, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/276921711/rep-of-ops-off-coast-of-normandy-france-during-66-2144-page-1-us-world-war-ii-war-diaries-1941-1945

Becton, F. J. War Diary for U.S.S. Laffey (DD-724) for April 1944. May 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78420781

Becton, F. J. War Diary for U.S.S. Laffey (DD-724) for February 1944. March 21, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78342297

Becton, F. J. War Diary for U.S.S. Laffey (DD-724) for June 1944. July 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/279779944/war-diary-61-3044-page-8-us-world-war-ii-war-diaries-1941-1945

Becton, F. J. U.S.S. War Diary for U.S.S. Laffey (DD-724) for March 1944. April 15, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78371003

Becton, F. J. War Diary for U.S.S. Laffey (DD-724) for May 1944. June 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78486951

Census Record for Robert C. Miller. April 18, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-9HC

Census Record for Robert Miller. April 9, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHM-FCN

Certificate of Birth for Charles Broadhart Miller, Jr. June 1, 1922. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DWBS-5F1

Certificate of Birth for Robert Curtis Miller. Undated, c. October 5, 1939. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YQM-QWJC

“Charles B. Miller, Jr.” The News Journal, February 15, 2015. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-news-journal-charles-miller-obit/158995457/

“City Baptists Burn Parsonage Mortgage.” Journal-Every Evening, May 7, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/158996573/

“City Signalman Killed in Action, Is Buried at Sea.” Wilmington Morning News, April 24, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/158997147/

“Convoy HX.254.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/hx/index.html?hx.php?convoy=254!~hxmain

Cox, Samuel J. “The Ship That Wouldn’t Die (2)—USS Laffey (DD-724), 16 April 1945.” H-Gram 045. 2020. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-045/h-045-1.html

Draft Registration Card for Robert Curtis Miller. June 30, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-D97R-F

Gragg, J. B. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for April 1945. May 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/140000144

Miller, Andrew G. “Report of Voyage, SS Paul H. Harwood, from New York to London.” September 16, 1943. Armed Guard Files, 1940–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Miller, Andrew G. “Reprt [sic] of Voyage, SS Paul H. Harwood, from London, England, to Philadelphia, Pa. (Paulsboro, N.J.).” October 15, 1943. Armed Guard Files, 1940–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Miller, Rose. Individual Military Service Record for Robert Curtis Miller. November 27, 1947. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20009/rec/3

Official Military Personnel File for Robert C. Miller. Official Military Personnel Files, 1885–1998. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Outerbridge, William W. “Action Report, U.S.S. O’BRIEN(DD725), 2–14 January 1945, Landing and Support of Assault Troops, U.S. Army, in Lingayen Gulf area, Luzon, P.I.” January 25, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139885554

Outerbridge, William W. “Action Report, U.S.S. O’BRIEN (DD725), 10 February 1945 to 1 March 1945, inclusive; Air Strikes against Tokyo, Japan and the Bonin Islands in Support of the Occupation of Iwo Jima by Task Force 58.” March 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139952840

Outerbridge, William W. “Action Report, U.S.S. O’BRIEN (DD725), 21 March – 4 April 1945, Operating in Task Group 51.1 During Landing and Support of U.S. Army and Marine Corps Troops on the island of Kerama Retto in the Nansei Shoto group of the Ryukyu Islands.” April 12, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139972539

Outerbridge, William W. “Action Report, U.S.S. O’BRIEN(DD725), Bombardment of Cherbourg, France, June 25, 1944.” June 29, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78630568

Outerbridge, William W. “War Damage to U.S.S. O’BRIEN (DD725) Incurred During Operations off Okinawa Jima, Ryukyu Islands, 27 March 1945 – Report of.” April 8, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139959662

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for August 1944. September 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78630066

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for December 1944. January 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139789660

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for February 1945. March 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139905013

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for January 1945. February 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139844824

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for July 1944. July 31, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78581629

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for June 1944. June 30, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78529398

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for March 1945. April 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/295920058/war-diary-31-3145-page-1-us-world-war-ii-war-diaries-1941-1945

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for November 1944. December 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78708378

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for October 1944. November 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78708359

Outerbridge, William W. War Diary for U.S.S. O’Brien (DD-725) for September 1944. October 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139757647

“Report of Changes Upon Sailing of U.S.S. O’BRIEN (DD725) for the 29th day of June, 1944, date of sailing.” June 29, 1944. Muster Rolls of U.S. Navy Ships, Stations, and Other Naval Activities, January 1, 1939 – January 1, 1949. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/sub-image/285524703/allard-paul-e-us-world-war-ii-navy-muster-rolls-1938-1949

“Robert Curtis Miller.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/141471448/robert-curtis-miller

“Two Delaware Men Give Lives.” Journal-Every Evening, April 24, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/158997361/

Waters, O. D. Jr. “Ship’s History, 8 February 1944 to 20 October 1945.” October 20, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/77660191

Last updated on January 28, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.