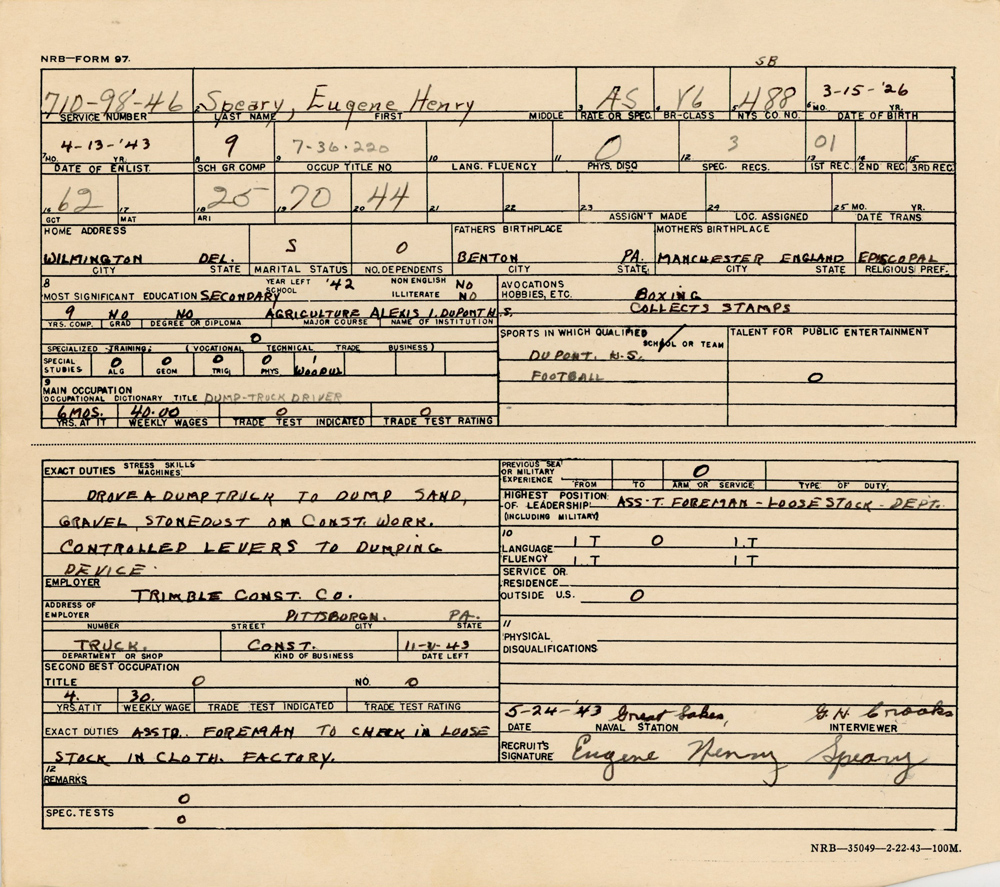

| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Dump truck driver for Trimble Construction |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Naval Reserve | 7109846 |

| Theater | Assignment |

| American (Atlantic) | U.S. Navy Armed Guard aboard S.S. J. Pinckney Henderson |

Early Life & Family

Eugene Henry Speary was born at 1804 Rising Sun Lane in Wilmington, Delaware, on the morning of March 3, 1926. He was the second child of Roy Taylor Speary (a gardener, 1900–1966) and Selina Speary (née Millington, 1905–1974). His father was from Pennsylvania, while his mother had been born in England. Speary’s older brother, Norwood L. Speary (1923–2014), also served in the U.S. Navy during World War II. His two younger brothers also served in the military after World War II: Carl S. Speary (1929–2004) and Kenneth L. Speary (1932–1975). A younger sister was born after his death.

It appears that the Speary family was not recorded on any indexed records from the 1930 census, though the next census stated that as of April 1, 1935, the family was living in the Stanton area of unincorporated New Castle County, Delaware. The family was still in or near Stanton when they were recorded on the 1940 census. When Speary’s father registered for the draft on February 16, 1942, he listed his address as North DuPont Road in Westover Hills, northwest of Wilmington.

Speary’s U.S. Navy personnel file stated that while still in school, he spent four years working in a clothing factory, checking in loose stock. He dropped out of school in 1942 after completing one year of high school at Alexis I. DuPont High School, where he played football. He was hired as a dump truck driver by the Trimble Construction Company, working there for six months at $40 a week before he entered the service. Curiously, the Wilmington Morning News reported that Speary “quit school to take a war job at the Dravo Corporation. He was working on construction work at the plant when he enlisted in the Navy.” There is no indication in his personnel file that Speary worked for Dravo, though the statement could potentially be reconciled if Trimble Construction did work at the shipyard.

According to his personnel file, Speary was living at 6 Main Street in Henry Clay, Delaware, when he entered the service in early 1943. The home, built c. 1820 on the west side of Brandywine Creek, is a short distance south of the historic Breck’s Mill and the Hagley Museum. (Henry Clay Village is close to Westover Hills, where the family was living as of 1942.)

Speary stood five feet, 10 inches tall and weighed 153 lbs., with blond hair and blue eyes. He was Episcopalian. Speary told the Navy that his hobbies were boxing and stamp collecting.

Military Career

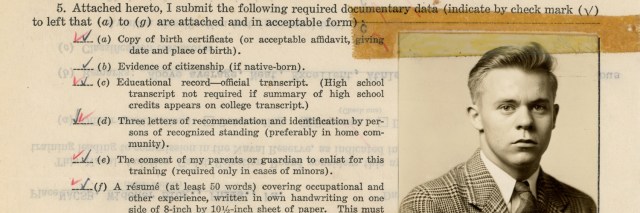

At the end of 1942, most voluntary enlistments in the U.S. armed forces ended by executive order, shifting responsibility to local draft boards to select virtually all the manpower required for the war effort. One exception was that 17-year-olds and men aged 38 and over could still volunteer. Speary could not have been drafted until his 18th birthday on March 3, 1944. However, he decided to volunteer for the U.S. Navy shortly after his 17th birthday. He was accepted at the Naval Recruiting Station, Wilmington, Delaware, on April 13, 1943. That same day, after traveling north, he enlisted as an apprentice seaman in the U.S. Naval Reserve at the Naval Recruiting Station, New York, New York. He was dispatched to the U.S. Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois, arriving the following day.

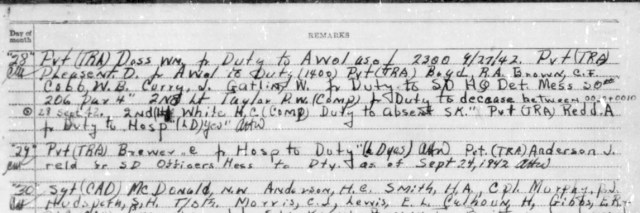

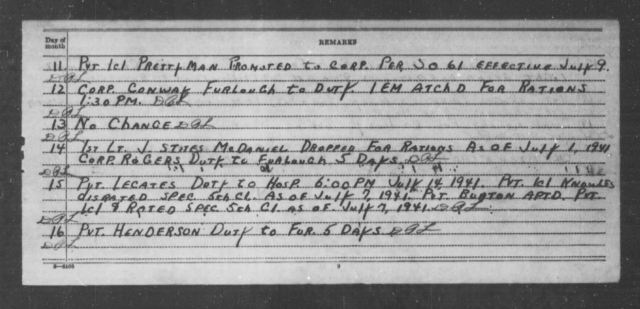

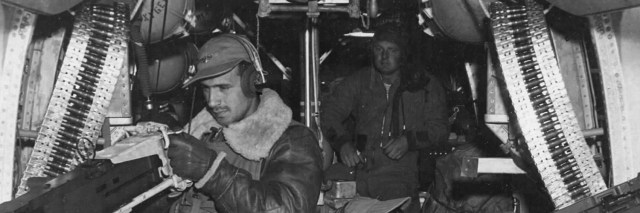

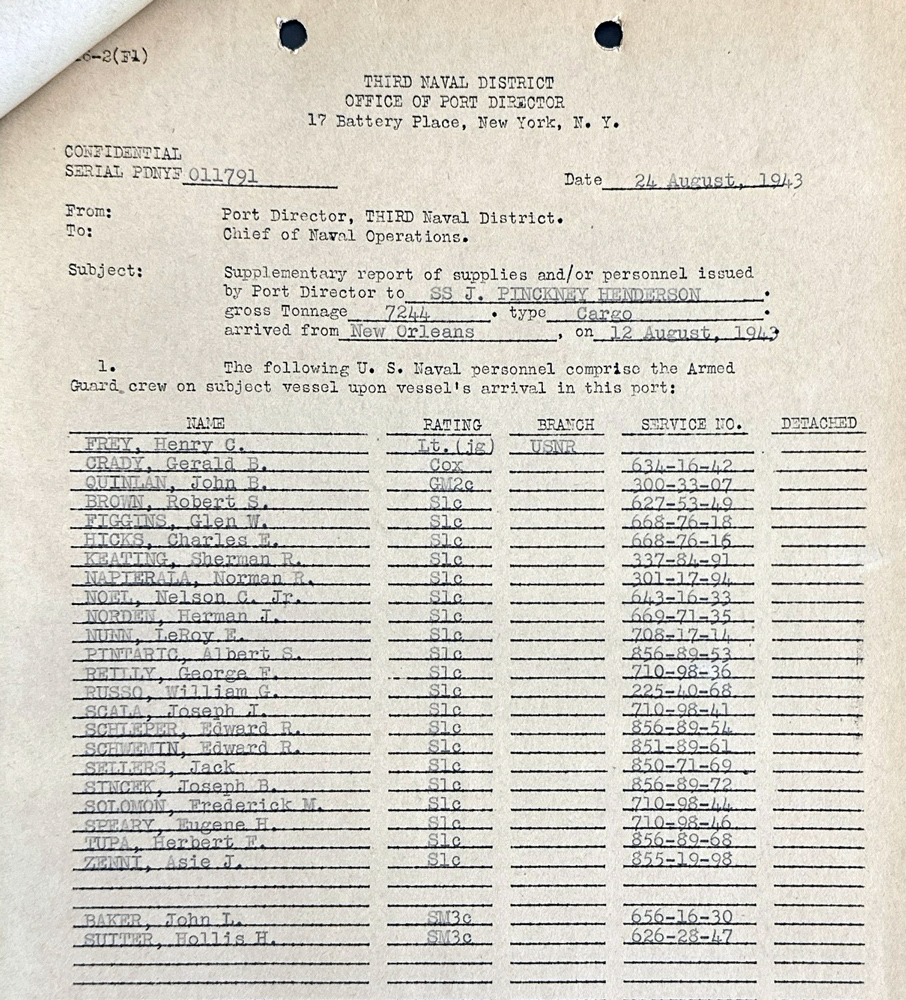

Upon completing boot camp on June 17, 1943, Speary was promoted to seaman 2nd class. On June 30, 1943, he was transferred to the U.S. Navy Armed Guard Center, New Orleans, Louisiana. The U.S. Navy Armed Guard (U.S.N.A.G.) manned guns aboard American and friendly foreign-flagged merchant ships. Speary boarded a train in Chicago, arriving in New Orleans on July 1, 1943. On July 11, 1943, he was assigned to detached duty as part of the U.S.N.A.G. compliment aboard the new Liberty ship S.S. J. Pinckney Henderson. Speary was promoted to seaman 1st class on July 16, 1943. The ship was completed by the Houston Shipbuilding Corporation in Houston, Texas, on July 19, 1943, and began sea trials. The Liberty ship was armed with a single 3-inch gun and nine 20 mm antiaircraft cannons.

Although owned by the War Shipping Administration, J. Pinckney Henderson was operated by the United Fruit Company under contract beginning on July 23, 1943. A few days later, she weathered the 1943 Surprise Hurricane at Houston, sustaining minor damage on the evening of July 27, 1943, when a barge cast adrift by the storm struck her stern.

J. Pinckney Henderson departed Houston on August 2, 1943. She joined eastbound Convoy HK-115 at Southwest Pass, at the mouth of the Mississippi River, arriving in the area of Key West, Florida, on August 7. She then joined northbound Convoy KN-257 on August 7, 1943, arriving in New York City on August 12.

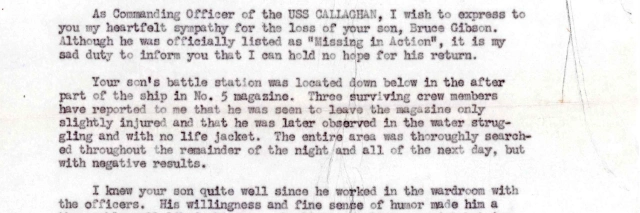

On September 18, 1943, the Wilmington Morning News reported:

Roy T. Speary of 115 East Summit Avenue, Richardson Park, received an early morning telephone message from his son, Seaman, first class, Eugene Henry Speary, four weeks ago that he would be home the next day for a few hours.

The next day went by without Seaman Speary arriving and his father dismissed the telephone call with the thought that his son had probably been given duties that prevented the trip.

Seaman 1st Class Speary must have called his father from New York sometime between August 12–14, 1943, but as it turned out, his ship was there only briefly. J. Pinckney Henderson departed New York City on August 14, 1943, in Convoy HX-252. The convoy was bound for the United Kingdom (Mersey, England, in J. Pinckney Henderson’s case, with a load of Lend Lease cargo). The first few days of the voyage were uneventful. However, on August 18, 1943, a thick fog descended on the convoy.

The convoy, which by this point included over 50 merchant ships, plus escorts, continued east at 9½ knots. The reduced visibility evidently resulted in poor stationkeeping, leading to tragedy around 0200 hours on August 19, 1943, about 170 nautical miles due south of Cape Race, Newfoundland.

A survivor aboard J. Pinckney Henderson recalled seeing a light to port. Suddenly, a ship appeared ahead in the fog with too little warning for either crew to evade. J. Pinckney Henderson’s bridge signaled the engine room to reverse engines, but before the order could be carried out, the Liberty ship struck the front starboard side of a tanker, M.S. J. H. Senior.

Both ships immediately burst into flames. The New York Times reported in an article the following year: “The Henderson was loaded to capacity with combustibles of the highest inflammability, including glycerine, resin, wax, oil, bales of cotton, and tons of magnesium and magnesite. The Senior was carrying high octane aviation gasoline.”

Confusion reigned in the immediate aftermath of the incident, which the crews of the convoy’s escorts initially believed to be the result of a submarine attack. Two other ships were also involved in collisions soon after, one of which sank.

Contemporary records indicate that 64 men aboard J. Pinckney Henderson perished, including all 26 members of the U.S.N.A.G. detachment. There were only three survivors from the J. Pinckney Henderson and six from J. H. Senior, who were rescued and brought to St. John’s, Newfoundland, for medical care.

In the meantime, the still-burning J. Pinckney Henderson was towed to Point Edward at Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, and beached on August 31, 1943. According to a synopsis in Speary’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.):

Immediately upon the vessel’s arrival at Sydney, the hulk was boarded by Canadian naval officers who found some thirty dead bodies of the crew but no living personnel. A guard was placed, Salvage operations were begun and twelve bodies removed. Fire and explosion necessitated suspension of the work until the following day, when twenty two more bodies, or fragments of bodies, were gathered and removed to the Lowden Funeral Parlour. […] Burial in a common grave was decided upon, and this took place with full naval honors on September 3 at the Hardwood Hill Cemetery, Sydney, with a band, firing squad and guard of honor from the American and Canadian naval vessels in port.

Despite the local firefighters’ best efforts, J. Pinckney Henderson burned for another three weeks. The last of the fire was finally extinguished on September 25, 1943. Little was recovered from the ship aside from the bodies: some fuel oil, the 3-inch gun operated by the U.S.N.A.G. compliment, and a load of copper from her cargo. The ship was refloated around November 1, 1943, and towed back to Staten Island, New York. Rehabilitating the vessel was infeasible and in late May 1944, she was towed to Philadelphia and scrapped.

After the war, 20 unidentified bodies were exhumed and repatriated to the United States. Army and Navy authorities concluded that these were “the Recoverable Remains, of the 50 Navy and Merchant Marine Personnel” still missing from the ship. These bodies—including, officially, Seaman 1st Class Speary—were buried as a group at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, Missouri, on June 17, 1949. That suggests that as many as 30 of the bodies officially accounted for were not, in fact, buried at Jefferson Barracks but were destroyed in the fire or lost overboard.

Seaman 1st Class Speary’s name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware. A stone memorial originally placed over the group burial in Canada was eventually put on display at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York.

Notes

Fatalities

Most accounts of the tragedy list different casualty figures for S.S. J. Pinckney Henderson. The New York Times reported on March 13, 1944, that 69 men were killed. In a 2017 article for the Cape Brenton Post, Rannie Gillis wrote that 64 men were killed. In a post about a memorial erected above the initial burial site in Canada, Mark Green wrote that 61 men were killed. Based on documents in Speary’s I.D.P.F., there were 67 men aboard, of whom 64 were killed. 14 men were identified and 50 bodies either lost or buried as a group.

Approximately 68 men were lost aboard J. H. Senor, indicating that there were about 132 total fatalities in the disaster.

Acknowledgments

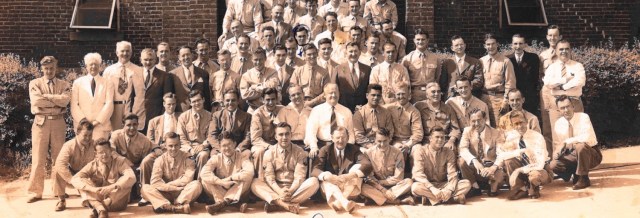

Special thanks to Rannie Gillis for information and to the Speary family for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“AOM3 Norwood LeRoy Speary.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/127897428/norwood-leroy-speary

“Carl Samuel Speary.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/41190057/carl-samuel-speary

Certificate of Birth for Eugene Henry Speary. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQM-QQVM

“Convoy HK.115.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/hk/index.html?hk.php?convoy=115!~hkmain

“Convoy HX.252.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/hx/index.html?hx.php?convoy=252!~hxmain

“Convoy KN.257.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/kn/index.html?kn.php?convoy=257!~knmain

Draft Registration Card for Roy Taylor Speary. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_02_00005-01143

Gillis, Rannie. “Sister ships.” Cape Brenton Post, March 25, 2017. https://www.pressreader.com/canada/cape-breton-post/20170325/282050506894095

Green, Mark. “They tried to bury this Memorial.” September 28, 2008. Southern Greens website. https://southerngreens.blogspot.com/2008/09/they-tried-to-bury-this-memorial.html

“Heavy Fire Loss.” Auke Visser’s International Esso Tankers site. https://www.aukevisser.nl/inter/id1184.htm

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Eugene H. Speary. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_649063_0460-03430

“J. Pinckney Henderson.” Armed Guard Files, 1940–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“J. Pinckney Henderson.” Armed Guard Files, 1940–1945: Vessels Scrapped or Lost. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“J. Pinckney Henderson (SS) (MCE #1938).” U.S. Maritime Commission Central Mail and Files Section, file no. 901-10895. Record Group 178, Records of the U.S. Maritime Commission. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Official Military Personnel File for Eugene H. Speary. Official Military Personnel Files, 1885–1998. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Only 9 on 2 Ships Survive Collision.” The New York Times, March 13, 1944. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1944/03/13/83966973.html?pageNumber=1

“Our Men and Women In Service.” Journal-Every Evening, June 30, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/137201373/

Reid, H. E. “Report from The Flag Officer Newfoundland (St. John’s) to The Commander-in-Chief, Canadian North West Atlantic, Halifax.” August 27, 1943. Warsailors.com. https://www.warsailors.com/convoys/hx252page4.html

“Roy T. Speary.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/213895202/roy-t-speary

“Seaman Missing in Action As Kin Await Visit Home.” Wilmington Morning News, September 18, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-morning-news-eugene-speary-mia/137202130/

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MR-MTB

Speary, Selina. Individual Military Service Record for Eugene Henry Speary. February 6, 1947. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20943/rec/2

Last updated on April 2, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.