| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| West Grove, Pennsylvania | Salesman and driver |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army Air Forces | 33787917 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | 498th Bombardment Squadron (Medium), 345th Bombardment Group (Medium) |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 748 (aerial engineer-gunner) | Pacific air campaign |

Early Life & Family

Amedeo Joseph Vincenti was born in West Grove, Pennsylvania, on April 23, 1909. Nicknamed Ami, he was the son of Armando Vincenti (a stone mason, 1881–1963) and Adelina Vincenti (née Di Giacomo, 1883–1913). His parents, Italian immigrants, had arrived in the United States a few years before his birth. He had two older sisters and two younger brothers.

Vincenti’s mother died of sepsis in 1913, when he was just four years old. His father remarried to Ginevra D’Alfonso (1886–1964), with whom he had four more daughters (one of whom died very young) and two sons.

The Vincenti family was recorded on the 1920 and 1930 censuses living at 156 Jackson Avenue in West Grove. The Oxford News described Vincenti:

He was graduated from the West Grove High School, class of 1926, and attended the Philadelphia Business College and the American School of Laundry at Joliet, Ill. He had been employed by the Sinclair Refining Co. before entering the service.

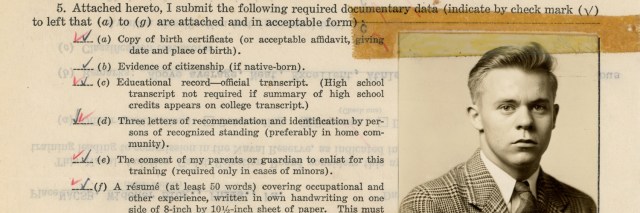

Vincenti’s enlistment data card described him as a high school graduate. If accurate, that would suggest that he did not complete a full year of college.

Vincenti was described as a salesman and a resident of West Grove when he married Sara Louise White (1911–2008) in New York City on September 23, 1939. His bride was a music teacher who had grown up a few blocks north of him.

It appears that neither Vincenti nor his wife were recorded on the 1940 census. However, later that year when he registered for the draft in Wilmington, Delaware—he must have been there on R-Day, October 16, 1940)—Vincenti listed his address as his father and stepmother’s home at 156 Jackson Avenue and his employer as the Staats Oil Company in nearby Malvern, Pennsylvania. The registrar described him as standing five feet, eight inches tall and weighing 182 lbs., with blond hair and blue eyes. On the other hand, military records describe him as five feet, nine inches tall and weighing 193 lbs., with blond hair and gray eyes. He was Catholic.

An annotation on his draft card indicated that Vincenti’s address changed to 621 Delaware Avenue in Wilmington on March 26, 1941. However, it was the Kennett Square Selective Service Board in Pennsylvania that drafted him two years later. His enlistment data card described his occupation as chauffeur or driver before entering the service.

Military Career

After he was drafted, Vincenti was inducted into the U.S. Army in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1943. Journal-Every Evening reported that he was among selectees who would leave for New Cumberland, Pennsylvania, on July 15, 1943. After classification there, he was assigned to the U.S. Army Air Forces. One of his brothers, Fred George Vincenti (1910–1965), and one of his half-brothers, Nicholas John Vincenti (1920–2018), also served in the U.S.A.A.F. during World War II.

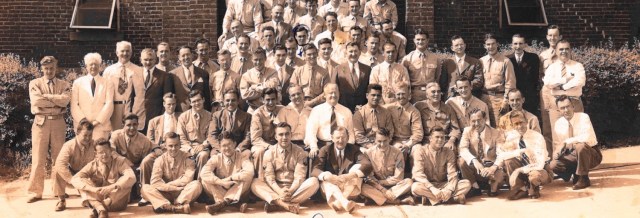

On July 20, 1943, Private Vincenti was one of 75 men from New Cumberland who began their basic training attached unassigned to the 1180th Training Group, Basic Training Center No. 10, Army Air Forces Eastern Technical Training Command, Greensboro, North Carolina. On October 9, 1943, he detached from the 1180th Training Group and attached for quarters, rations, administration, and training to Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment, 302nd Training Wing, also located at Basic Training Center No. 10.

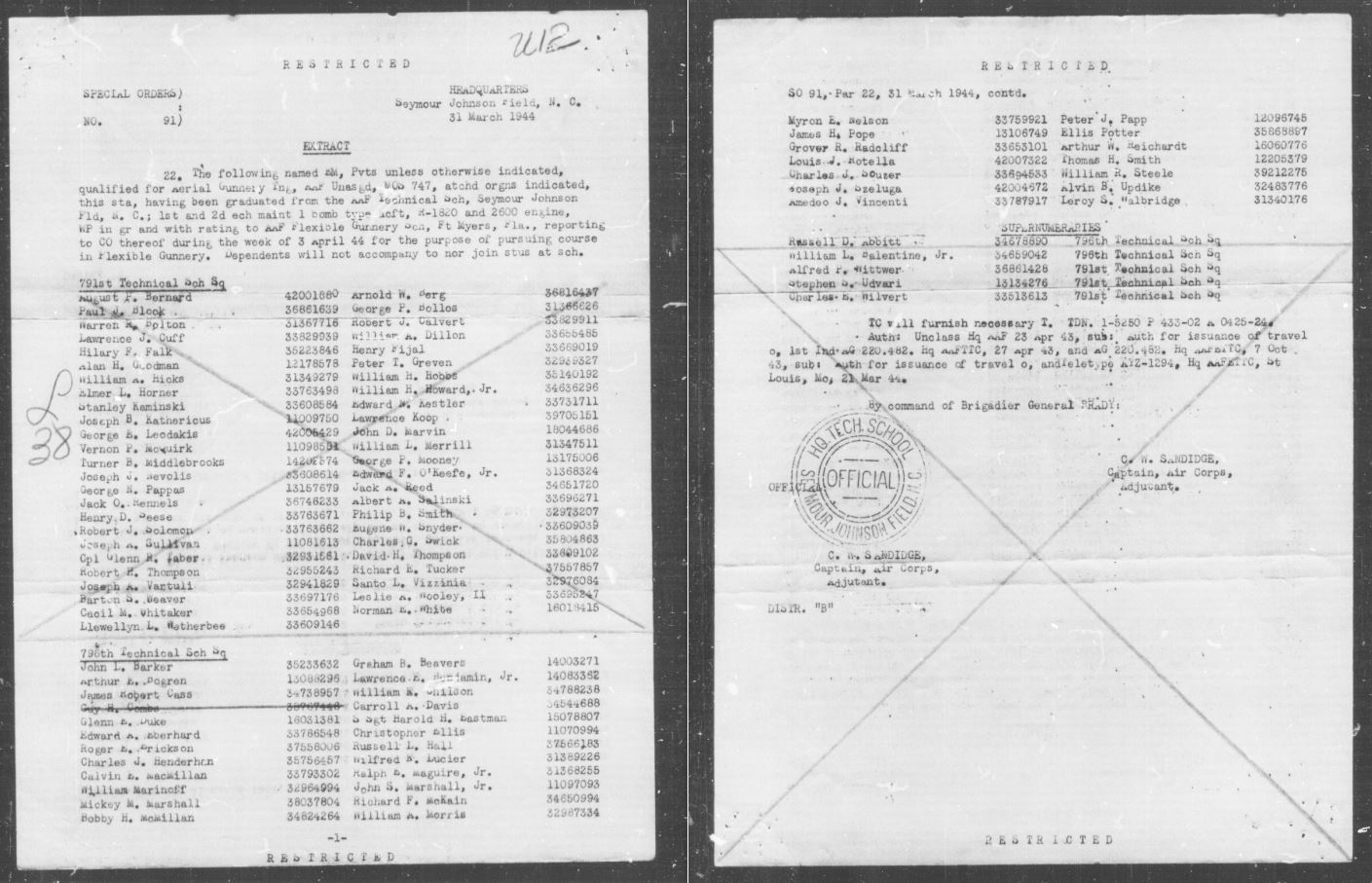

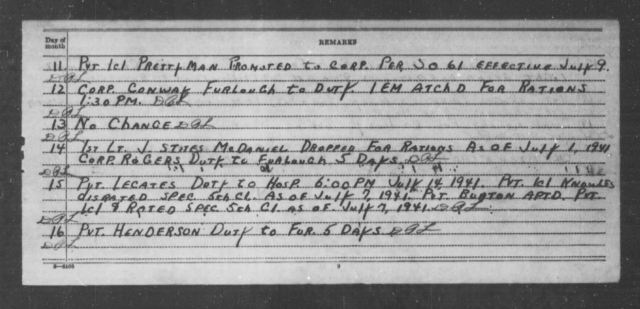

As of November 16, 1943, Vincenti’s military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code was recorded as 629, student. On that date, he was released from attachment to the 302nd Training Wing and dispatched to Seymour Johnson Field, North Carolina, to attend Airplane Mechanic School (Basic Course). After reporting for duty there on November 19, 1943, he was attached unassigned to the 797th Technical School Squadron. On January 17, 1944, Private Vincenti was released from attachment to that squadron and attached to the 794th Technical School Squadron. On February 12, 1944, he was detached from the 794th Technical School Squadron and attached to the 796th Technical School Squadron.

By March 31, 1944, Private Vincenti had been trained in first and second echelon maintenance for “1 bomb type” aircraft, as well as maintenance of the Wright R-1820 Cyclone and R-2600 Twin Cyclone engines, qualifying him in the M.O.S. of 747, airplane and engine mechanic.

On April 7, 1944, Journal-Every Evening reported:

Private Amedeo J. Vincenti was graduated this week as an aircraft mechanic from Seymour Johnson Field, N. C., after completing a course in aircraft maintenance and repair. He is the son of Mr. and Mrs. Amedeo [sic] Vincenti of West Grove, Pa. His wife, Mrs. Sara L. White Vincenti, lives at 621 Delaware Avenue, this city.

Some U.S.A.A.F. mechanics were strictly ground personnel, while others trained as aircrew. On the evening of April 3, 1944, Private Vincenti was detached from the 796th Technical School Squadron and was dispatched to the Army Air Forces Flexible Gunnery School, Fort Myers, Florida.

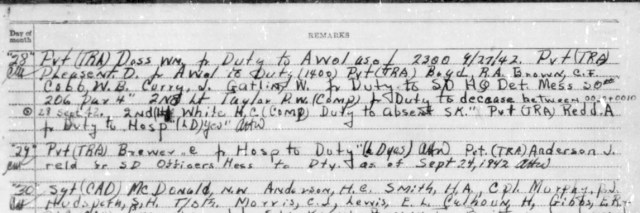

After gunnery training, Vincenti may have been stationed at Goldsboro, North Carolina, until July 15, 1944. Regardless, Vincenti then moved to Columbia Army Air Base, South Carolina, where the U.S.A.A.F. trained crews to operate the North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. He was stationed there until December 6, 1944, and according to the Oxford News went overseas in January 1945. Morning reports recorded Vincenti’s M.O.S. as 748, airplane mechanic-gunner or aerial engineer-gunner. On a bomber crew, the position filled by men of that M.O.S. was referred to as flight engineer.

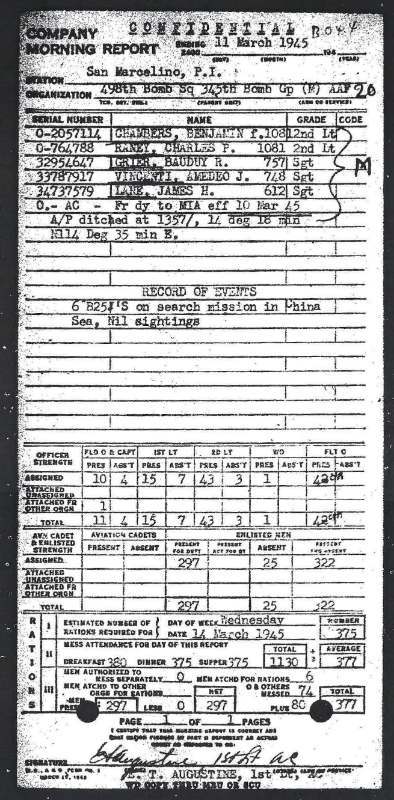

Corporal Vincenti was one of 10 men who joined the 498th Bombardment Squadron (Medium) at Tacloban, Leyte, Philippine Islands, on January 26, 1945. These men, most likely representing two five-men crews, included three men who would be flying with Vincenti on his final mission: pilot 2nd Lieutenant Benjamin F. Chambers (1924–1945), armorer-gunner Corporal James H. Lane (1924–1945), and a fellow Delawarean, radio operator-mechanic-gunner Corporal Bauduy R. Grier (1925–2017). Journal-Every Evening stated of Grier in an article printed on April 11, 1945: “His parents pronounce their son’s first name ‘Boa-dee,’ but he’s ‘Boddie’ to his buddies[.]” Vincenti, Grier, and Lane were all promoted to sergeant prior to March 10, 1945.

Part of the 345th Bombardment Group (Medium) of the U.S. Fifth Air Force, the 498th Bomb Squadron had been activated on September 8, 1942, at Columbia Army Air Base. The squadron arrived in Brisbane, Australia, during May 10–26, 1943, and flew its first combat mission on June 21, 1943. Their B-25s carried no bombardier, with the nose instead equipped with .50 machine guns for strafing ground targets.

Available unit records list only the lead pilot participating in each mission. Since Vincenti joined the unit at the same time as Lieutenant Chambers, it is likely that they were in the same crew and may even have flown all their missions together. However, the absence of loading lists makes it impossible to confirm any of Vincenti’s missions except his last. It appears Chambers and his crew did not fly any combat missions until after the 498th Bomb Squadron’s air echelon moved to San Marcelino, Luzon, Philippine Islands, on the night of February 12–13, 1945.

Lieutenant Chambers’s first six missions were:

- February 18, 1945: Six B-25s bombed and staffed enemy troops along the Bagac–Pilar road.

- February 19, 1945: Six B-25s bombed and strafed troop concentrations “along North side of road between Bagac Village –– Pilar Village.”

- February 20, 1945: Nine B-25Js attacked ground targets on Formosa, damaging or destroying warehouses, barracks, a radio station, and railroad rolling stock.

- February 25, 1945: Seven B-25Js took off on an antishipping strike, but Chambers aborted due to mechanical difficulties.

- March 2, 1945: Eight B-25Js attacked the airfield at Toyonara, Formosa.

- March 6, 1945: Eight B-25Js attacked the airfield at Samah, Hainan.

Final Mission

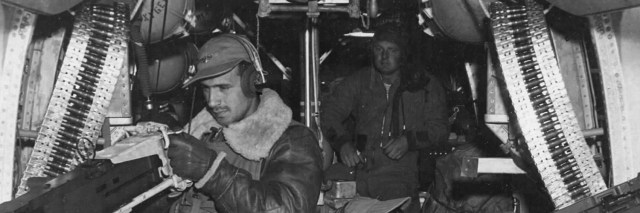

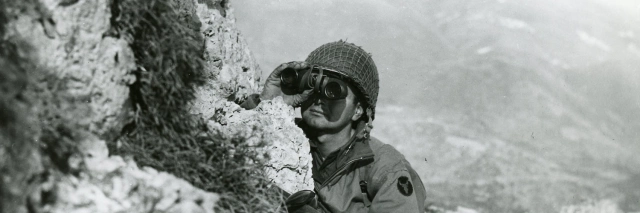

On the morning of March 10, 1945, Sergeant Vincenti boarded B-25J serial number 43-36044, which took off from San Marcelino around 0700 hours, piloted by 2nd Lieutenants Chambers and Charles P. Raney (1922–1945). Their mission, along with five other B-25s, was to conduct an antishipping strike in the South China Sea off the coast of Japanese-occupied French Indochina—present day Vietnam—from Cape Batangan (Ba Làng An Peninsula) to Qui Nhen (Quy Nhon). It was about a three-hour, 45-minute flight to the target area. As flight engineer, Sergeant Vincenti would have manned the top turret in combat, a position that gave him a clear view of the engines.

The B-25s were armed with 500 lb. bombs equipped with delay action fuzes for skip bombing. Skip bombing required the attacking aircraft to fly extremely low, releasing the bomb at close range to skip along the water like a child throwing a rock in a pond. Ideally, the bomb struck the side of the enemy ship, sank, and detonated below the waterline. Unlike an aerial torpedo, it was nearly impossible for the target ship to evade a well-aimed skip bombing attack. It was also significantly more dangerous for the attacking aircraft.

According to the mission report, all six aircraft attacked a small tanker at 13° 47’ North, 109° 14’ East, Quy Nhon, with each element of two bombers making two passes to strafe and skip bomb. The mission report recorded only a single hit:

Lt. Thomes A/P [airplane] 655 on his second pass scored a direct hit at the water line amid ship resulting in a large explosion and fire with smoke rising to 8000 feet. Capt. Cranford A/P 265 bombs on his second pass skipped over the ship onto shore starting a large oil tank afire.

On the other hand, the unit history for the month stated: “Several direct hits were scored, resulting in a large explosion with smoke and flames. The decks were awash when A/P’s left target.”

Although the contemporary reports did not mention any hits by Lieutenant Chambers’s aircraft, Lawrence J. Hickey later wrote in his book, Warpath Across the Pacific: The Illustrated History of the 345th Bombardment Group During World War II, that “Chambers skipped a 500-pound bomb directly into the side of the ship, but the delay fuse malfunctioned and it blew up directly beneath the B-25 as it passed over the deck.”

Hickey did not name the source for his statement about the premature bomb detonation, but it may have been what Lieutenant Chambers announced over the intercom after the aircraft was severely rattled by an explosion. Hickey wrote: “To Bauduy Grier, who was in the radio compartment in the back of the plane, the impact from the explosion felt like being hit on the bottom of his feet with a baseball bat.”

Whether the blast was indeed caused by a premature detonation or caused by something else, such as a secondary explosion from the ship’s volatile cargo, there was no immediate sign of damage and the aircraft headed back east across the South China Sea.

Captain Elmo L. Cranford (1923–1945), Vincenti’s flight leader, later recalled in a statement that about one hour after the attack, Vincenti’s plane “developed trouble in the left engine. Lt. Chambers pilot of this ship was unable to contact us by radio due to my radio set being out.”

It was suspected, though not confirmed, that the explosion back at Quy Nhon had damaged the engine. Hickey wrote:

The plane had reached roughly the halfway point on the 700-mile journey home when it suddenly began vibrating severely. Grier looked out the side window and saw smoke streaming back from the left engine. A fragment from the premature bomb explosion had apparently put a small hole in an oil line and the lubricant had slowly drained away.

Captain Cranford continued:

Lt. Chambers gained altitude to fifteen hundred feet using partial power on his left engine. The engine finally cut completely, but Lt. Chambers contacted my left wingman and told him that he was unable to feather the propeller and he would have to ditch.

Put simply, Chambers and Raney climbed while they still had two engines. That gave them more breathing room when the engine did fail, since they could trade altitude for speed. Once the engine failed, they attempted to position the propeller blades on the non-operative engine so that the edge of the blade faced forward, but the feathering system did not function correctly. Although a B-25 was capable of flying on one engine, the pilots’ inability to feather the propeller increased drag and fuel consumption. Windmilling of the propeller may have also made the plane difficult to control. For these reasons, they deemed it impossible for them to get back to base and too dangerous to try to make it closer to friendly territory.

Assuming he had not already done so to help the pilots troubleshoot the engine problem, Sergeant Vincenti would have exited the top turret to help jettison equipment. Not only would that lighten the bomber, reducing fuel consumption, but it also prevented them from becoming projectiles in the event of a water landing. Meanwhile, in the back of the plane, Sergeants Grier and Lane jettisoned their machine guns, ammunition, and the plane’s radio. Once the pilots announced their intention to ditch, each crew member was to remove parachute harnesses and anything else that might present an entanglement hazard before moving to their ditching stations. As flight engineer, Sergeant Vincenti would have braced himself sitting with his back against Lieutenant Chambers’s seat.

Hickey continued:

Grier left his head set on and could hear the co-pilot, 2/Lt. Charles P. Raney, cooly reading off the altitude as the plane dropped towards the surface of the ocean: “500 feet, 300, 200, 100. Brace yourself, we’re going to hit!” Out the side window Grier could see only water. He ripped off the head set and threw it. The plane slid between two large swells, then rammed directly into another. It was like hitting a brick wall at a hundred miles an hour. Grier immediately blacked out.

Chambers and Raney ditched their aircraft at 1317 hours in the South China Sea at approximately 14° 18’ North, 114° 35’ East, about halfway between Indochina and the Philippines. Even under perfect conditions, water landings subjected crewmembers to massive forces. A 1944 pilot’s manual stated: “When ditched, the B-25 loses its forward speed after the second impact in slightly more than its own length.” The three men at the front of the plane bore the brunt of the impact and were likely killed or incapacitated in the crash.

After Grier regained consciousness, he called to the men up front, but they did not reply. He found that the nose of the plane was already submerged. Whether or not they survived the impact against the swell, it appears clear that Sergeant Vincenti and the pilots were unable to exit the plane before it sank. Grier and Lane managed to escape through the waist gun window. Captain Cranford continued:

The ship was afloat for one minute and thirty seconds, and when the ship was half submerged the life raft was seen to inflate. I personally did not see any survivors until the airplane had completely submerged. My crew and I both sighted two survivors in water near the raft. We called for rescue from the ground station and were acknowledged. Due to my limited gas supply I could only circle for about three minutes after the airplane had submerged. The weather was good in the area with five miles visibility and a northwest wind at 30 knots per hour. Large swells were prevalent on surface of water.

Hickey wrote that “Grier had been a lifeguard back in his home town of Wilmington, Delaware,” and tried to assist Sergeant Lane. However, the men were separated when Grier swam after the plane’s life raft, which was drifting away in the heavy seas. Lane was never seen again.

During the next two days, the 345th Bomb Group searched for the missing crew without success. Alone in the raft, Sergeant Grier tried to sail east to the Philippines but found himself drifting with the current. He rationed his water supply for over two weeks, but eventually resorted to taking small sips of seawater.

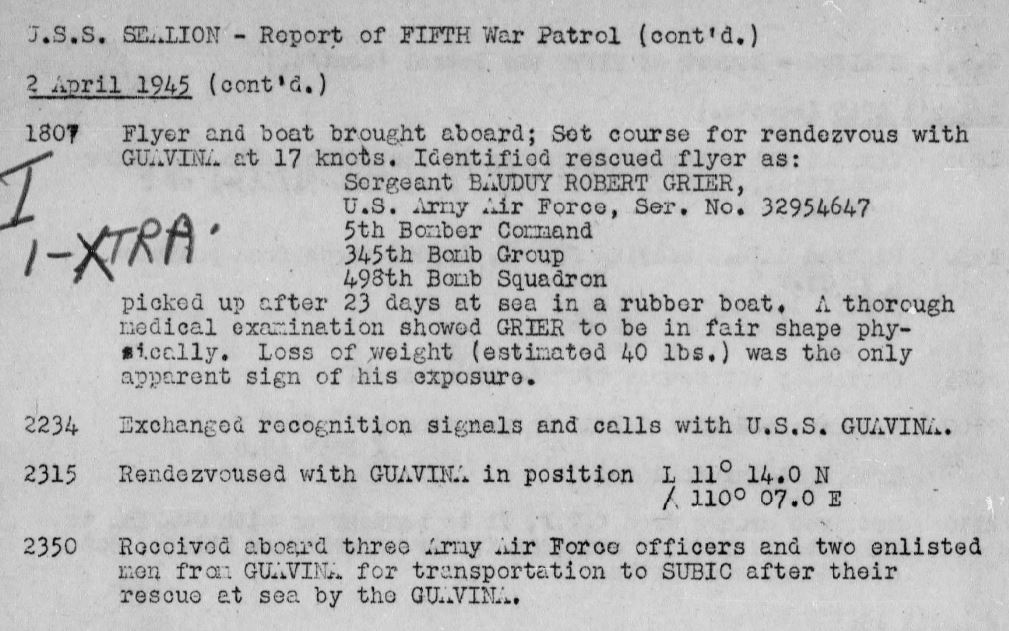

On the evening of April 2, 1945, 23 days after the crash, Sergeant Grier was rescued by the submarine U.S.S. Sealion (SS-315). Sealion’s crew recorded his position at 9° 47’ North, 109° 53’ East, about 243 nautical miles southwest of the reported crash site. He had lost about 40 lbs. during his ordeal at sea. Journal-Every Evening later reported: “Below deck he spotted a drinking fountain [scuttlebutt] and broke away from the sailors to gulp avidly. Somewhat sheepishly he added, ‘They had to drag me away.’” The submarine docked at Subic Bay, Luzon, Philippine Islands, on April 6, 1945, and Sergeant Grier was transferred to the hospital.

In 1949, a board of officers declared the bodies of Sergeant Vincenti and the other missing members of his crew non-recoverable. Vincenti’s personnel effects included a ring, a souvenir ammunition box, and a bow with four arrows.

Vincenti’s widow, Sara, remarried in 1956 to James J. Welsh, III (1920–1993).

Sergeant Vincenti is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and on a memorial in West Grove. Although he had been living in Wilmington when he entered the service and was listed as a Delawarean on the official 1946 U.S. Army casualty list, his name was omitted from the Delaware memorial volume and at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Crew of B-25J 43-36044 on March 10, 1945

The following list is based on a copy of a missing air crew report in Sergeant Vincenti’s individual deceased personnel file, with grade, name, service number, position, and status (killed in action or returned to duty).

2nd Lieutenant Benjamin F. Chambers, O-2057114 (pilot) – K.I.A.

2nd Lieutenant Charles P. Raney, O-764788 (copilot) – K.I.A.

Sergeant Amedeo J. Vincenti, 33787917 (flight engineer) – K.I.A.

Sergeant Bauduy R. Grier, 32954647 (radio operator) – R.T.D.

Sergeant James H. Lane, 34737579 (tail gunner) – K.I.A.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Sandra White Milledge for supplying a photo of Vincenti from the files of Sara White Vincenti Welsh, and to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for morning reports that establish when Vincenti and his crew joined their squadron and their military occupational specialties.

Bibliography

“78 Inducted From Kennett.” Journal-Every Evening, July 7, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/131604214/

“Bauduy Robert Grier Sr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/177094686/bauduy-robert-grier

Census Record for Ameda Vincenti. April 15, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4639694_00358

Census Record for Ameda Vincenti. January 15, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4383861_00485

Draft Registration Card for Amedeo Joseph Vincenti. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Pennsylvania, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44033_10_00407-00051

Enlistment Record for Amedeo J. Vincenti. July 1, 1943. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=33787917&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=4244668

Hickey, Lawrence J. Warpath Across the Pacific: The Illustrated History of the 345th Bombardment Group During World War II. 5th ed. International Historical Research Associates, 2008.

“Historical Data Pertaining to the 498th Bombardment Squadron (M) 8 September 1942 – 19 December 1945.” April 28, 1954. USAF Archives, Research Studies Institute, Maxwell Air Force Bace, Alabama. Reel A0624. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Amedeo J. Vincenti. Army Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1942–1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Kuechler, R. F. “Narrative Report, Mission FFO 69-D-23, 10 March 1945.” March 12, 1945. 345th Bomb Group website. http://345thbombgroup.org/pdf/mission-reports/498th/1944_05-1945_05.pdf

Morning Reports for 498th Bombardment Squadron (M), 345th Bombardment Group (M). January 1945 – March 1945. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

Morning Reports for 796th Technical School Squadron. April 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-04/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0390/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0390-01.pdf

Morning Reports for 796th Technical School Squadron. February 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-02/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0288/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0288-09.pdf

Morning Reports for 797th Technical School Squadron. November 1943 – January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0467/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0467-19.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0056/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0056-01.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0056/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0056-02.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0430/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0430-11.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0430/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0430-12.pdf

Morning Reports for 1180th Training Group. July 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0076/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0076-09.pdf

Morning Reports for Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment, 302nd Training Wing. October 1943 – November 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-10/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0383/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0383-14.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0466/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0466-18.pdf

“Our Men and Women In Service.” Journal-Every Evening, April 7, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/131604086/

Oxford News, May 3, 1945. Article title unknown, from a newspaper clippings card about Sergeant Vincenti at the Chester County History Center.

Pilot Training Manual for the B-25 Mitchell Bomber. November 1944. Headquarters, AAF Office of Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Training. https://ia601902.us.archive.org/9/items/PilotTrainingManualForTheMitchellBomber/PilotTrainingManualForTheMitchellBomber_text.pdf

Putman, Charles Francis. “U.S.S. SEALION – Report of War Patrol Number FIVE.” April 6, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139985623

“Sara White Welsh.” The News Journal, February 16, 2008. https://www.newspapers.com/article/131604377/

“Wilmingtonian Adrift 24 Days On Life Raft.” Journal-Every Evening, April 11, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/137481896/

Wolf, William. North American B-25 Mitchell – The Ultimate Look: From Drawing Board to Flying Arsenal. Schiffer Military History, 2008.

Last updated on December 7, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.

Amedeo J. Vincenti was my uncle. I have copies of newspaper articles relevant to his last flight that were passed down to me as well as a Vincenti genealogy. I would like to contact Sandra White Milledge. Could help me accomplish this?

Richard D. Vincenti

rvincenti237@comcast.net

LikeLiked by 1 person

Correction to article about Amedeo Vincenti. Amadeus had two younger brothers, Uncle Fred and my father Dante F Vincenti, born June 29, 1912, 11 months before Adeline died.

LikeLike