| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware | Chemist’s helper at the DuPont Experimental Station |

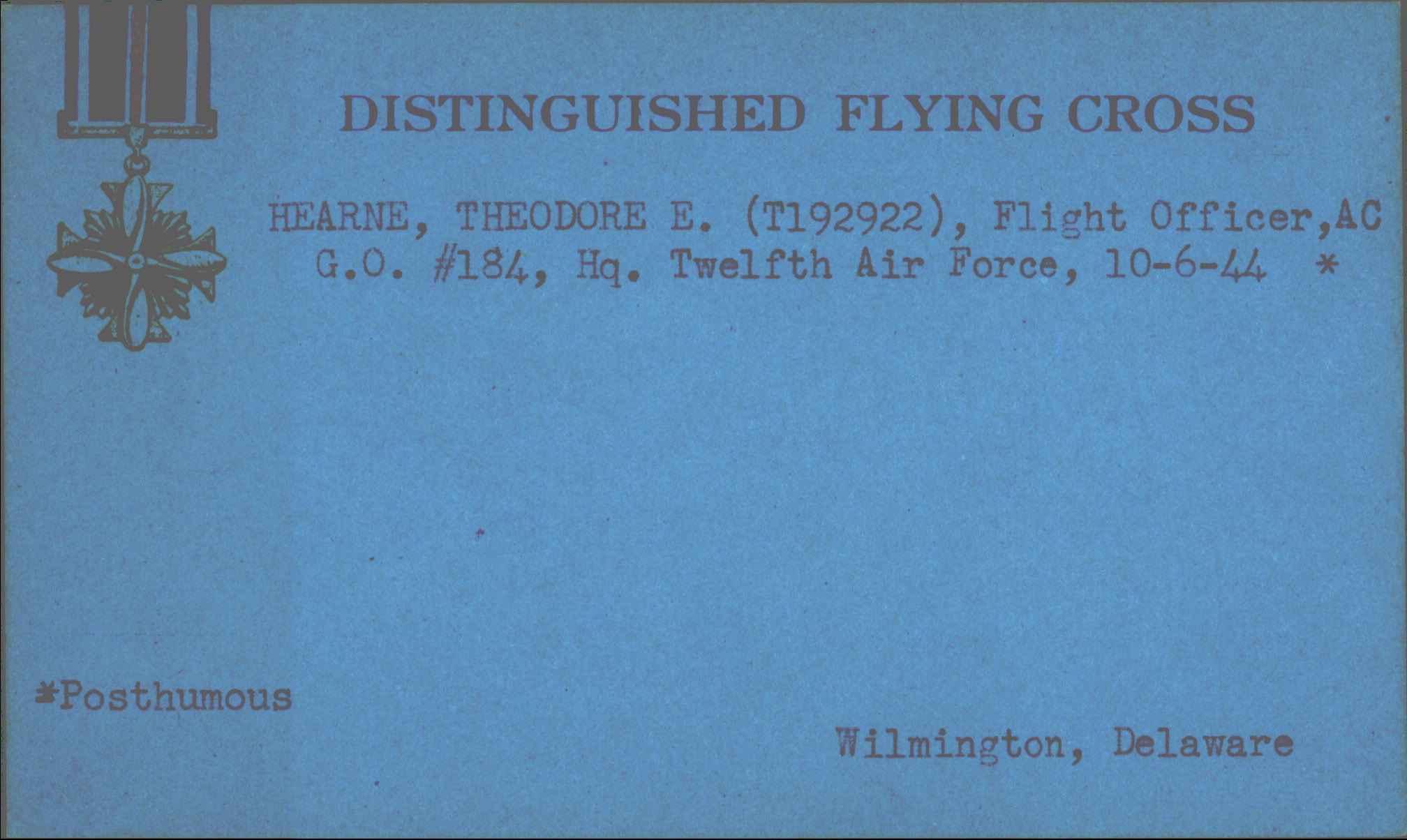

| Branch | Service Numbers |

| U.S. Army Air Forces | Enlisted 20255838 / Officer T-192922 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | 417th Night Fighter Squadron |

| Military Occupational Specialty (Presumed) | Awards |

| 0520 (radar observer, night fighter) | Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart |

Early Life & Family

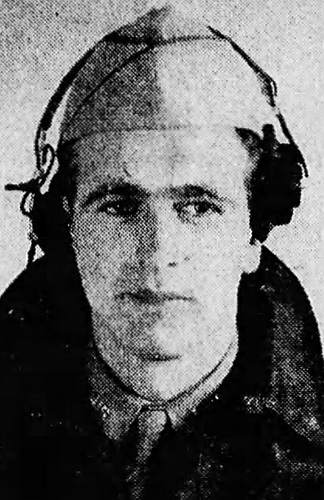

Theodore Edward Hearne was born in Chester, Pennsylvania, on May 31, 1920. Nicknamed Ted, he was the first child of Isaac John Hearne (1891–1961) and Elva Hearne (née Foraker, 1900–1990). During World War I, Hearne’s father served in the fledging Aviation Section, Signal Corps, U.S. Army, a forerunner of the U.S. Army Air Forces and the U.S. Air Force.

Hearne had six younger brothers and four younger sisters. It appears that his family moved to Maryland shortly after Hearne was born, since his parents’ next four children were born there between October 27, 1921, and March 7, 1926. Two were born in towns on Maryland’s Eastern Shore (Pittsville and Berlin) and it appears the next two were born in Baltimore.

By August 16, 1927, the family had moved to the area of Andrewville, Delaware, an unincorporated area of Mispillion Hundred in Kent County just west of the town of Farmington. Hearne’s father was farming at the time. Prior to August 16, 1929, the family had moved to Rockland, north of Wilmington, Delaware. They were also recorded as living in Rockland when the next census was taken in April 1930. Hearne’s father was described as a mechanic at a paper mill.

By the time of the next census, taken in April 1940, the Hearne family was living in Representative District 6 in unincorporated New Castle County, Delaware. It is possible that they were still living in Rockland, though Representative District 6 included other areas to the north and northeast of Wilmington. Both Hearne and his father were working in the chemical industry (undoubtedly the DuPont Company): Hearne as a chemist’s helper and his father as a stationary fireman.

Journal-Every Evening stated of Hearne: “Before entering the service he was employed at the DuPont Experimental Station for three years.” Census records and Hearne’s enlistment data card both stated that his highest level of completed education was one year of high school.

Hearne’s military paperwork described him as standing five feet, seven inches tall and weighing 165 lbs., with dark brown hair and blue eyes. He was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

National Guard & Early World War II Service

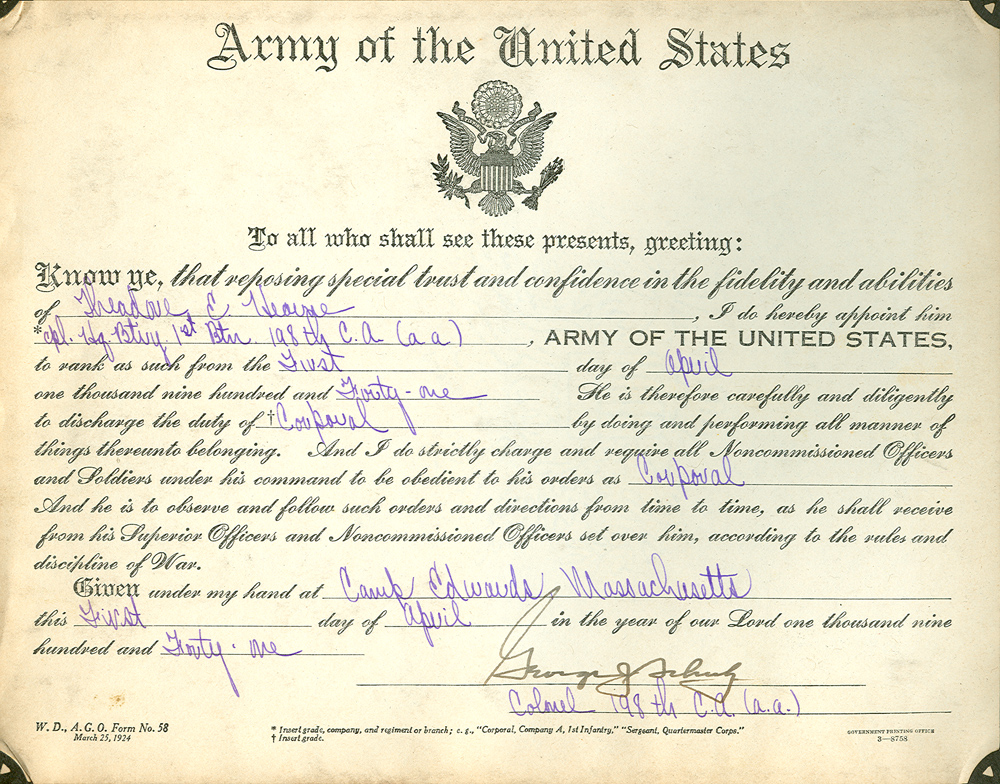

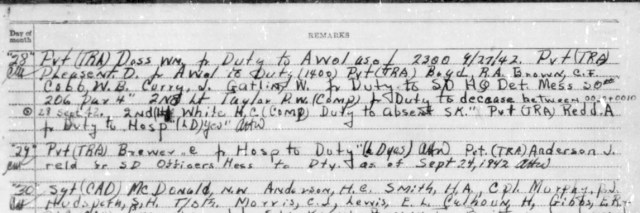

According to his father’s statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission, Hearne joined the Delaware National Guard (D.N.G.) on September 17, 1937, while a roster states he joined or reenlisted in the D.N.G. on September 12, 1938. Private Hearne was a member of Headquarters Battery, 1st Battalion, 198th Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft), when he went on active duty after his unit was federalized in Wilmington, Delaware, on September 16, 1940. His brother, Private John Thomas Hearne (1921–1974), was in the same battery. Shortly thereafter, the regiment moved to Camp Upton, New York.

Unit rosters indicate that Hearne was promoted to private 1st class in October 1940. Journal-Every Evening reported on January 21, 1941, that “Privates Charles L. Sharpe and Theodore E. Hearne, Headquarters Battery, First Battalion, have been relieved from special duty at the regimental pump.” Presumably, that refers to the special duty noted on a roster as of December 15, 1940.

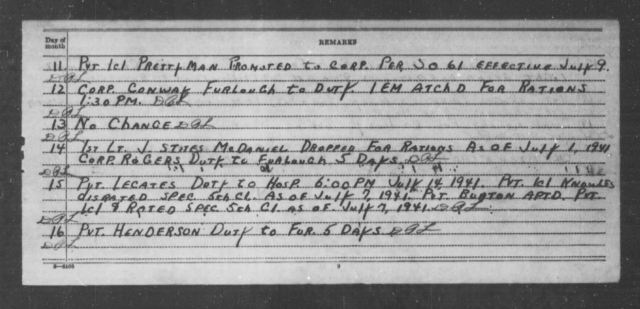

On March 26, 1941, the 198th moved to Camp Edwards, Massachusetts. On April 1, 1941, Hearne was promoted to corporal. He was still serving in the 1st Battalion’s Headquarters Battery. The following day, the Wilmington Morning News reported that Corporal Hearne was among a group of men “ordered to attend the 36th Coast Artillery Brigade Intelligence School. This school includes instruction in map reading, camouflage, scouting and patrolling, and identification of aircraft.”

Beginning in September 1941, the 198th served at Fort Ontario, New York. Although the continental United States was quite safe from any major direct attack, fears ran high in the days after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. As a result, the regiment was dispatched to East Hartford, Connecticut, a potential target due to the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company factory there. About six weeks later, in mid-January 1942, the 198th moved to South Carolina.

Corporal Hearne and his comrades shipped out of the Charleston Port of Embarkation on January 27, 1942, bound for the Pacific Theater via the Panama Canal. The regiment arrived at Bora Bora, Society Islands, French Polynesia, on February 17, 1942, as part of an American task force which occupied and began building a base there as part of an effort to secure sea lines of communication between the United States and Australia. The 198th manned antiaircraft positions on the island as a contingency against Japanese attack, though none materialized. Some of the unit’s more promising enlisted men were transferred back to the United States for officer training.

Five of Hearne’s siblings served in the military during World War II. After serving in the 198th Coast Artillery and a successor unit, the 736th Antiaircraft Gun Battalion, John T. Hearne returned to the continental United States and was stationed at Camp Hood, Texas. Sergeant Rodney Lee Hearne (1923–2006) served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during the war. After the war, he was a member of the Air National Guard and eventually became a chief petty officer in the U.S. Naval Reserve. Technician 5th Grade Jean Elizabeth Hearne (later Barthelson, 1925–2012), a member of the Women’s Army Corps, served with the Army Air Forces as an “Air W.A.C.” Seaman 1st Class Robert Alfred Hearne (1926–1986) served in the U.S. Naval Reserve. Carpenter’s Mate 3rd Class James Andrew Hearne (1927–1950) served in the U.S. Naval Reserve with the Seabees during World War II, and briefly with the Air National Guard and U.S. Air Force postwar. Following in the footsteps of his six older siblings, Hearne’s youngest brother, Airman 2nd Class Alvin Warner Hearne (1936–2001), also served in the U.S. Air Force postwar.

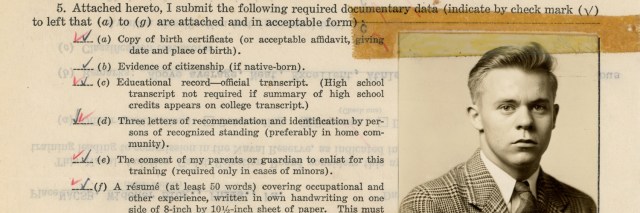

Army Air Forces Training

Evidently Corporal Hearne volunteered for flight training. On November 22, 1942, he was reclassified as an aviation cadet and transferred out of the 198th Coast with orders to report to the U.S. Army Air Forces Classification Center, Nashville, Tennessee, upon his return to the continental United States. The Wilmington Morning News reported on February 11, 1943, that Hearne was one of seven aviation cadets from Delaware who were currently in the preflight phase of pilot training at Maxwell Field, Alabama.

Hearne completed the preflight phase of pilot training around March 1943 and was transferred to the 60th Army Air Forces Flying Training Detachment at the Lodwick School of Aeronautics near Lakeland, Florida, to begin the second (primary) phase of pilot training. During April and May 1943, he logged 40 hours and 19 minutes of flying time as a student pilot, including 18 hours and 48 minutes as student first pilot, all flying Boeing Stearman PT-17 biplanes. He did not successfully complete primary training and was reassigned on May 11, 1943, transferring out of the 60th A.A.F.F.T.D. on May 29.

Aviation cadets dropped from pilot training were often moved into other training programs, such as bombardier, navigator, or gunner. In Hearne’s case, he shifted to training as an airborne radar operator, technically known as radar observer or radio observer. As of October 28, 1943, when he had a flight physical at the Station Hospital, Army Air Forces School of Applied Tactics, Orlando Army Air Base, Florida, Aviation Cadet Hearne was attached to the 348th Night Fighter Squadron as a student.

The 348th Night Fighter Squadron, an operational training unit, was activated on October 1, 1942, at Orlando Army Air Base, Florida. From the summer of 1943 onward, the 348th, 349th, and 420th Night Fighter Squadrons were under the 481st Night Fighter Operational Training Group. A document dated February 16, 1944, described the 481st Night Fighter Operational Training Group’s three-phase night fighter crew training program. Pilots started with the 348th Night Fighter Squadron “and, upon completion of the course, are fully qualified night pilots.” During the second phase, the pilots and radar observers trained together with the 349th Night Fighter Squadron. The summary continued:

The final (or Advanced) stage of training takes place in the 420th Night Fighter Squadron, Hammer Field, Fresno, California. At the end of the three months of work, the combat crews are then ready for assignment to tactical squadrons beginning unit training, or as replacements for immediate shipment overseas.

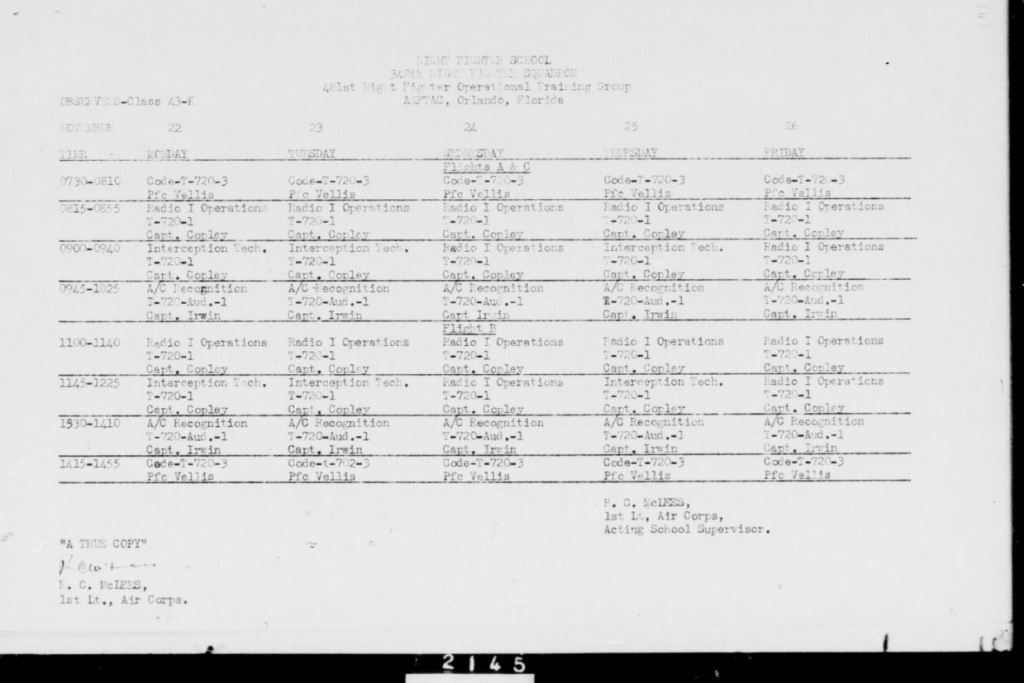

Aviation Cadet Hearne was a member of the 348th Night Fighter Squadron’s Observers Class 43-K, which ran at Orlando Army Air Base from November 1, 1943, to November 26, 1943, with weekends off. Topics included communications, code, parachutes, aircraft recognition, and interception techniques.

After completing the course, on December 1, 1943. Hearne was attached as a student to the 349th Night Fighter Squadron at Kissimmee Army Air Field, Florida. By the end of 1943, Hearne had logged 87 hours and 25 minutes of flying time with the U.S.A.A.F (including the hours from his pilot training). His name appeared on a roster compiled on or around January 3, 1944, when the 349th was ordered to move to Hammer Field, near Fresno, California.

Upon completing his training with the 349th Night Fighter Squadron, on February 1, 1944, Hearne was rated as a radar observer and appointed to the grade of flight officer. That same day, he was transferred to the 420th Night Fighter Squadron, also located at Hammer Field. Flight Officer Hearne participated in only a single flight during February 1944, which took place in a Douglas P-70 Nighthawk on February 2, 1944.

The Wilmington Morning News reported on February 18, 1944, that Flight Officer Hearne “attended aerial gunnery school and radar school after returning to this country from overseas duty with the 198th Coast Artillery” and “is now home on leave with his parents[.]” After his leave, Hearne returned to the 420th at Hammer Field.

March 1944 was a far busier month for Flight Officer Hearne. He logged 55 hours and 15 minutes in the air, mostly aboard P-70s, as well as four hours in instrument trainers.

On April 1, 1944, the night fighter training squadrons were deactivated and reorganized as squadrons within various Army Air Force base units, which typically consolidated multiple existing units at a given field. The 420th Night Fighter Squadron became Squadron “C,” 450th Army Air Forces Base Unit. Flight Officer Hearne logged four hours of flight time at Hammer Field in early April 1944. On April 15, 1944, he transferred to the 451st A.A.F.B.U. at Salinas Army Air Base, California. As of April 21, 1944, Flight Officer Hearne was serving with that unit’s Squadron “B,” which had been the 348th Night Fighter Squadron until the beginning of that month. Hearne logged another six hours, 15 minutes in the air with the 451st A.A.F.B.U. between April 22 and May 2, 1944.

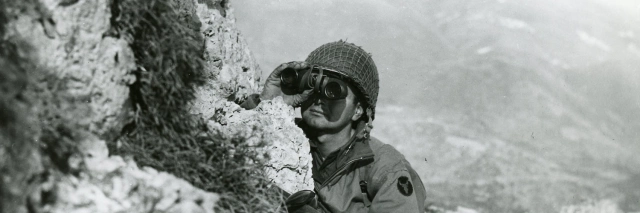

Combat in the Mediterranean Theater

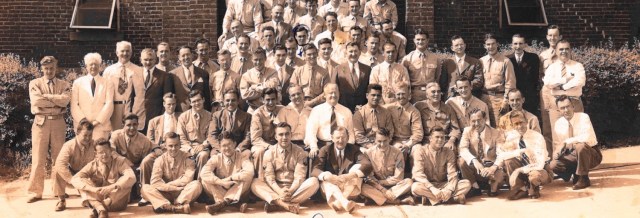

According to his father’s statement, Flight Officer Hearne went overseas by air from New York to Algiers, Algeria. He joined the 417th Night Fighter Squadron of the 63rd Fighter Wing at Borgo Aerodrome (aérodrome de Bastia-Borgo), on the French island of Corsica, probably around mid-June 1944.

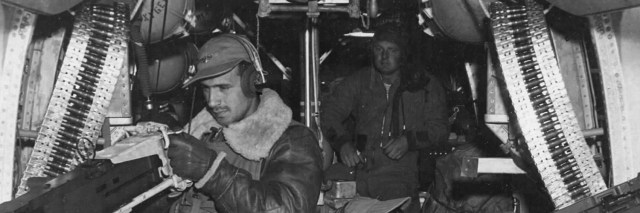

The 417th Night Fighter Squadron had been activated at Kissimmee, Florida, on February 20, 1943, with the first of its personnel arriving on March 5. That spring, the unit went overseas to the United Kingdom. Since there was not yet an adequate American-designed night fighter available, the 417th was trained and equipped with the British-designed Bristol Beaufighter. Each night fighter was crewed by a pilot and a radar observer. During the summer of 1943, the squadron moved to the Mediterranean Theater. The unit moved to Corsica in late April 1944, and resumed combat missions on April 29.

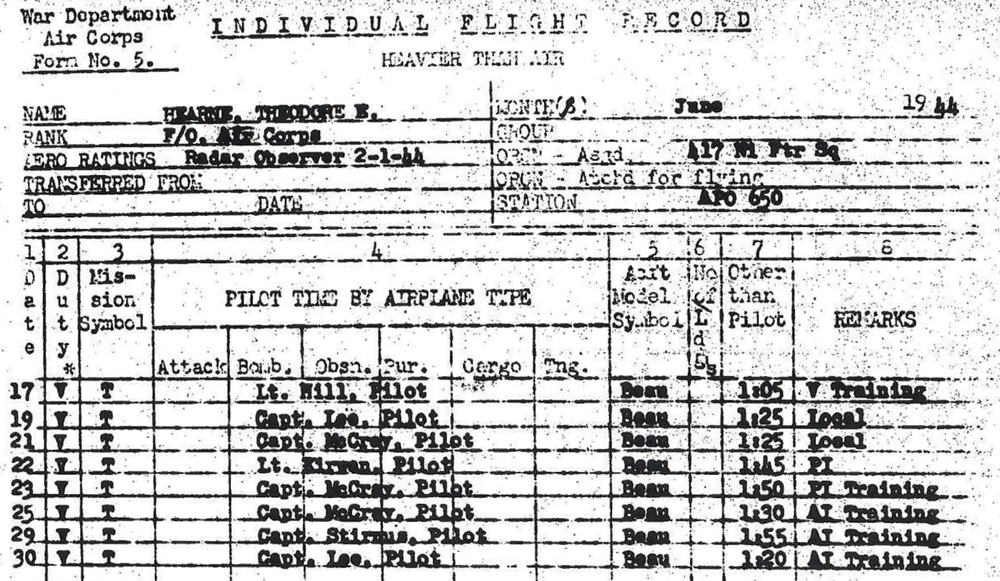

Hearne began training flights in the 417th Night Fighter Squadron’s Beaufighters on June 17, 1944. During the month, he logged 12 hours and 15 minutes of training flights with five different pilots.

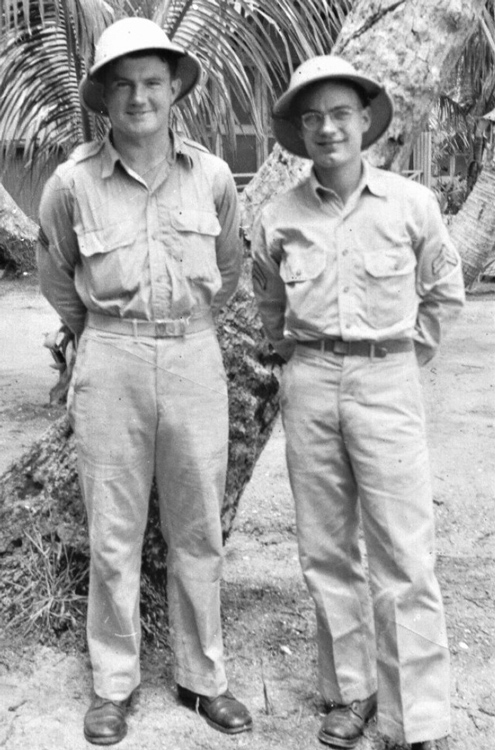

On July 5, 1944, Flight Officer Hearne’s new partner, 2nd Lieutenant Robert Ward Inglis (1921–1944), joined the squadron. The two men most likely knew each other from training. Lieutenant Inglis was in the 348th Night Fighter Squadron’s Pilot Class 43-K, which overlapped with the squadron’s Observers Class 43-K. Both men were attached to the 349th Night Fighter Squadron when it relocated from Florida to California in January 1944. Like Hearne, Lieutenant Inglis had originally been a member of the National Guard in a Coast Artillery unit. His unit, part of the Oregon National Guard, had been federalized the same day as Hearne’s: September 16, 1940. Inglis had received his pilot’s wings and commission as a 2nd lieutenant on or about July 27, 1943, at Williams Field, Arizona.

From July 7, 1944, onward, Flight Officer Hearne flew exclusively with Lieutenant Inglis. During the next eight days, they flew seven training missions totaling 14 hours in the air. They flew their first two combat missions on July 16, 1944: a two-hour, 45-minute air-sea rescue mission, followed by a two-hour, 35-minute patrol. They flew a one-hour training mission on July 17, followed by a 30-minute training mission on July 18. Later on July 18, they flew their third combat mission, a three-hour, five-minute patrol.

Final Mission

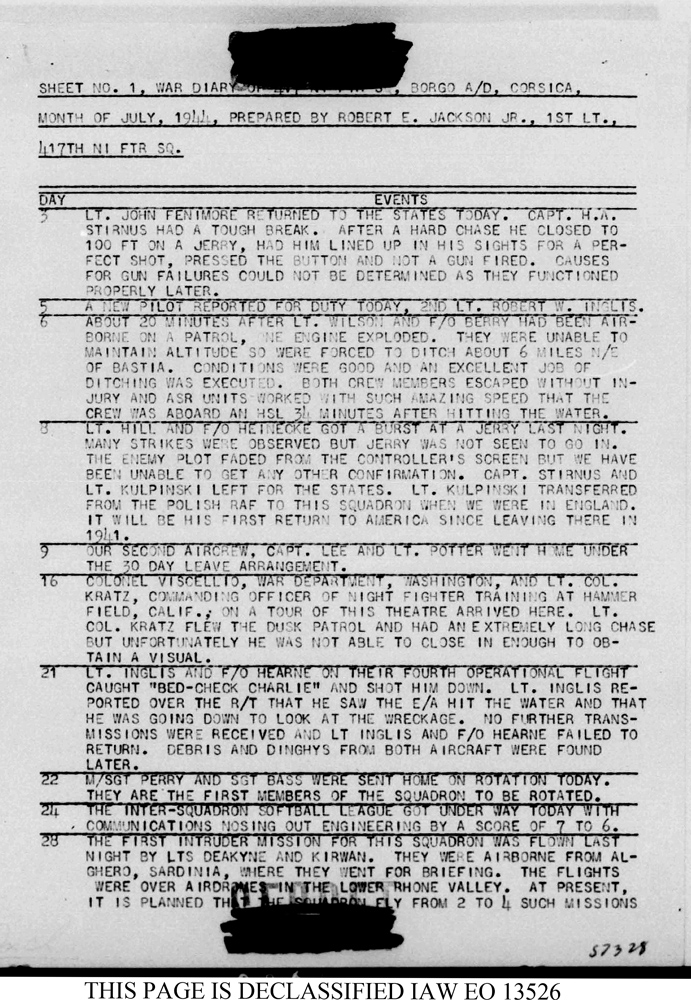

While flying from Corsica, the men of the 417th Night Fighter Squadron had a nemesis known as Bedcheck Charlie: a singular, uncanny foe that proved both tough and elusive.

Bedcheck Charlie was a slang term that Allied troops in the European and Mediterranean Theaters used to describe a solitary German plane performing night nuisance raids. In most cases, it did little more than disrupting Allied soldiers’ sleep—hence the name—but unlucky G.I.s in the plane’s path might be subjected to a rain of the lethal antipersonnel weapons known as “butterfly bombs.” Of course, there were many German aircraft that flew such missions during the war. It is probable that even the so-called Bedcheck Charlie that the 417th Night Fighter Squadron pursued for nearly three months was in fact several different aircraft. Indeed, various 417th air crews identified Charlie as a Junkers Ju 88 or the similar Ju 188.

The first tangle with Bedcheck Charlie recorded in the 417th Night Fighter Squadron’s war diary took place on May 1, 1944. The enemy plane, identified as a Ju 88, was damaged but not destroyed. The war diary reported that by May 9, 1944, the 417th’s crews were competing to shoot down Charlie. Each crew that encountered but failed to destroy Charlie had to contribute $5.00 to a pool that was to be claimed by the crew that finally brought Charlie’s career to an end. The squadron’s war diary documented a total of six encounters with solitary enemy aircraft between May 1, 1944, and July 19, 1944. Four crews fired upon Charlie but none were able to confirm the destruction of the enemy plane.

In his book, Beaufighters in the Night, Lieutenant Colonel Braxton “Brick” Eisel wrote:

Even high-ranking visitors from the United States had a go at ‘Charlie’. […] Colonel Winston Kratz, the commander of the night-fighter training in California, visited the operational units to see how he could improve the training for his students. A very experienced pilot, he flew a sortie starting at dusk on 16 July. GCI [ground control interception] vectored him onto a contact at extremely long range, but after an exhausting chase he was unable to close for a visual. The ‘bogey’ [unidentified aircraft] got away and Kratz gave his $5.00 to the squadron.

Around 2144 hours on July 20, 1944, 2nd Lieutenant Inglis took off from Borgo with Flight Officer Hearne as radar observer aboard a Beaufighter Mk.VIF, serial number ND 262, for a patrol east of Corsica. It was their fourth combat mission with the 417th Night Fighter Squadron and would prove to be their first crack at Bedcheck Charlie.

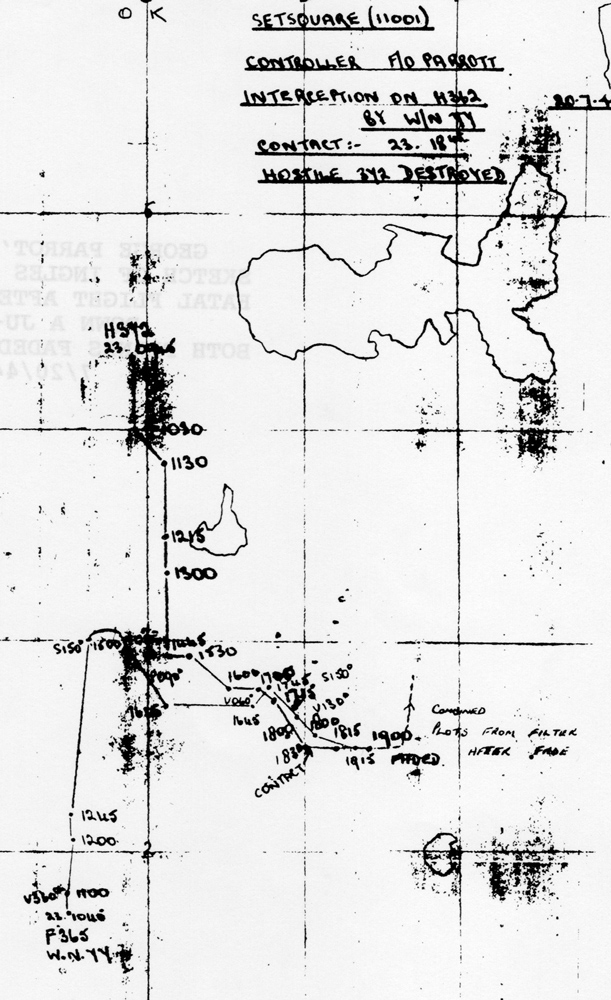

It was a dark night with no moon. The weather was favorable and the sky clear except for a layer of stratocumulus clouds at about 1,500 feet. At 2310 hours, a British ground-based radar unit, No. 11001 Air Ministry Experimental Station at Prunete, Corsica, detected a single unidentified aircraft flying south over the Tyrrhenian Sea. (Air Ministry Experimental Station, or A.M.E.S., was the official name for Royal Air Force radar stations during the war, though the technology had matured considerably since 1939.)

The British controller vectored Inglis and Hearne toward the bogey. Five minutes later, the ground control station confirmed the plane was an enemy aircraft (bandit) based on identification friend or foe (I.F.F.). The contact, designated Hostile 372 by the ground station, passed west of the island of Pianosa, Italy, then turned southeast toward mainland Italy. At 2318 hours, Hearne acquired the bandit on his airborne radar and guided Lieutenant Inglis to a successful interception over the Tyrrhenian Sea due south of the island of Elba, Italy.

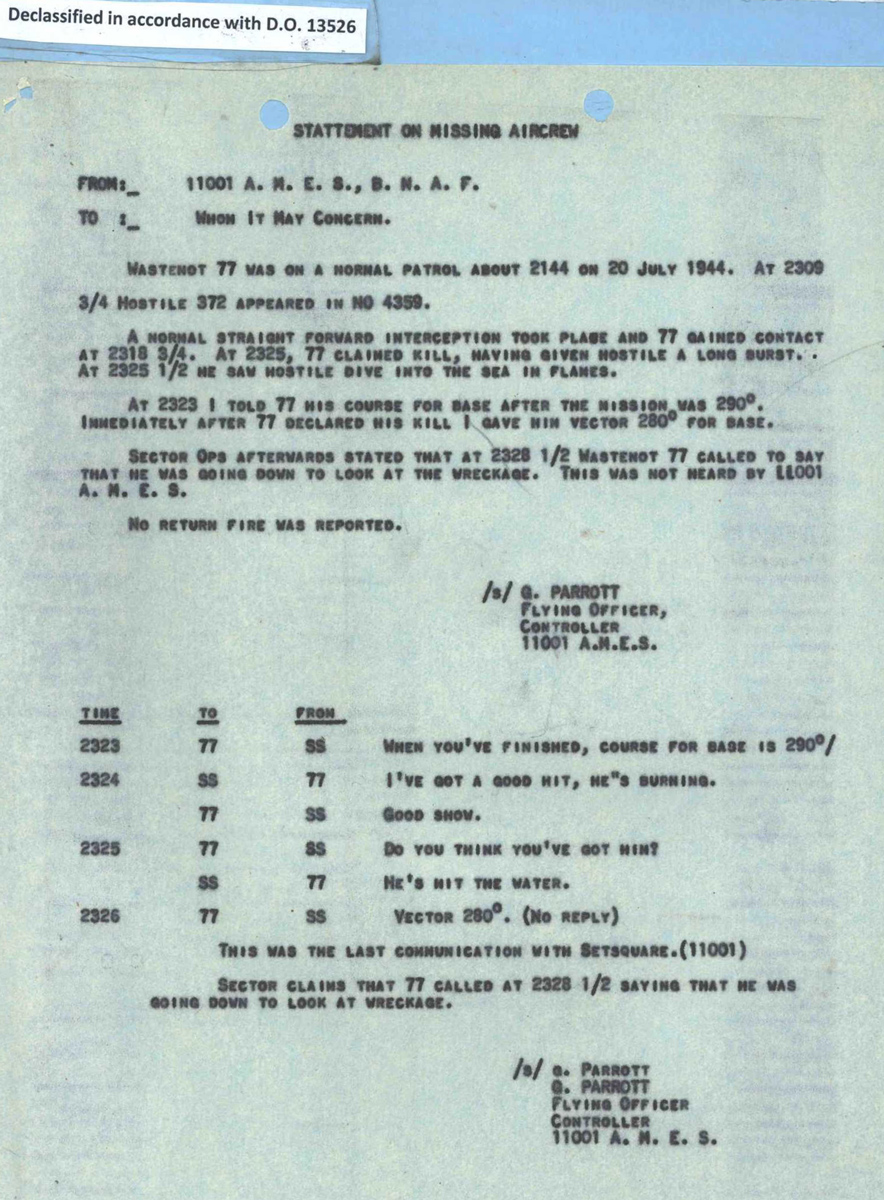

Remarkably, a Royal Air Force controller, Flying Officer George Parrott, provided investigators with a transcript of some of the last transmissions between 11001 A.M.E.S., callsign Setsquare, and Inglis and Hearne’s Beaufighter, callsign Wastenot 77.

Setsquare: “When you’ve finished, course for base is 290°.” (2323 hours)

Wastenot 77: “I’ve got a good hit, he’s burning.” (2324 hours)

Setsquare: “Good show.” (2324 hours)

Setsquare: “Do you think you’ve got him?” (2325 hours)

Wastenot 77: “He’s hit the water.” (2325 hours)

Setsquare: “Vector 280°.”

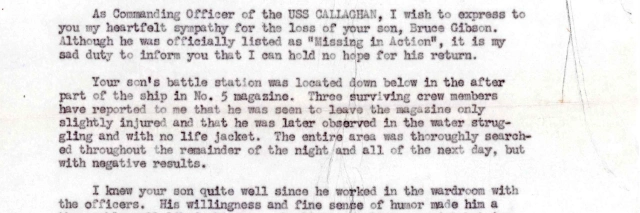

The controller reported that he did not hear any further transmissions from the Beaufighter, though Sector Operations later reported hearing a transmission at 2328 hours that Wastenot 77 had announced they were going to decrease altitude to examine the wreckage. No further radio transmissions from Wastenot 77 were received ashore and the plane never returned to base.

The Beaufighter’s last known position was 42° 25’ North, 10° 15’ East, about 4¾ nautical miles northeast of the island of Montecristo and about 18½ nautical miles due south of Cape Poro, Elba. Beginning at dawn, Allied air and surface craft searched for the missing plane. They discovered oil, both German and British-manufactured dinghies, unidentified life vests, and debris, some of which was identified as that of a Beaufighter. No survivors or bodies were found.

Beyond the fact that both Wastenot 77 and Hostile 372 had crashed into the sea, it is unclear what happened. The most likely explanation is that on this extremely dark night, Lieutenant Inglis let his altitude get too low while investigating the downed enemy plane and crashed into the ocean. Today such an incident would be referred to as a controlled flight into terrain. There was no evidence that another enemy aircraft shot down the Beaufighter. If there were any other planes in the area, they were not detected by the British ground radar operators. There was also no report from Wastenot 77 that their Beaufighter had been damaged by return fire from Bedcheck Charlie.

There is another possibility, albeit one for which there is no direct evidence. During the fall of 1944, the 417th Night Fighter Squadron experienced engine failures at an extremely high rate, resulting in several crashes. The squadron’s own investigation implicated two problems. The first was that the Beaufighters were war weary aircraft that saw a great deal of action in British service prior to being turned over to the Americans. (Though it could be considered a self-serving conclusion, the squadron’s investigation blamed the age of the aircraft for the high rate of mechanical problems rather than maintenance mistakes by ground personnel.) Some crashes were also blamed on rainwater contaminating fuel due to uncovered drums. The latter problem occurred after the squadron moved to mainland France and there is no evidence the drums were left uncovered in Corsica.

The Inglis-Hearne crash was not mentioned in a report about the crashes—the earliest incident mentioned occurred October 15, 1944—suggesting that investigators did not believe it was related. However, the October 15 incident was not the first case in which a plane was lost due to engine failure. Indeed, two weeks before Inglis and Hearne disappeared, on July 6, 1944, an engine suddenly exploded on a patrolling 417th Night Fighter Squadron Beaufighter, forcing its crew to ditch. If one of Inglis and Hearne’s Beaufighter’s engines had suddenly failed at low altitude while investigating the crashed enemy aircraft, Inglis could easily have lost control of the aircraft and crashed.

Eisel wrote that the Bedcheck Charlie pool, “grown now to a fair size, paid for a bittersweet party for the squadron.”

On August 7, 1944, Journal-Every Evening reported that Hearne was missing in action. Flight Officer Hearne was held as missing in action until September 12, 1944, when his status was changed to killed in action. Journal-Every Evening announced his death on September 14, 1944.

An inventory of Flight Officer Hearne’s personal effects included a photograph of his brother, Rodney, a leather wallet, his Delaware driver’s license, tour tickets, an opera ticket, two prayerbooks, and four autographed banknotes (American, Portuguese, Moroccan, and French Indochinese currency). Known as short snorters, these were autographed by traveling companions, presumably during his journey across the Atlantic and possibly to Corsica.

In a letter to the Army Effects Bureau at the Kansas City Quartermaster Depot written around December 1944, Flight Officer Hearne’s father wrote that his son “had worked very hard [and] had worked his way up[.]” Although still holding out hope that his son would be found alive, he added: “I have lost a very good boy [and] we all are going to miss him very much. May god bless him where ever he is[.]”

2nd Lieutenant Inglis and Flight Officer Hearne were posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for the aerial victory on their last flight. At a ceremony at New Castle Army Air Base on April 6, 1945, Lieutenant Colonel William B. Hooton, commander of the 2nd Ferrying Group, presented the medal to Flight Officer Hearne’s mother. The Wilmington Morning News reported:

The citation which states that Flight Officer Hearne displayed “superior professional skill as he directed his pilot in pursuit of the fleeing aircraft,” disclosed that Hearne was a member of the crew of a Beaufighter type plane which on a night patrol off Corsica contacted a JU-88.

The German plane dived to minimum altitude and attempted to shake off pursuit. But the American plane, with Flight Officer Hearne guiding the chase, caught the JU-88 and shot her down. The citation praises the officer’s “outstanding proficiency in combat and steadfast devotion to duty.”

Hearne was also awarded the Purple Heart.

After the war, the Army reviewed the case and was unable to find any unidentified bodies that were likely matches to Inglis or Hearne, nor anything in German records that would shed light on the case. As a result, their bodies were declared non-recoverable. Curiously, their names are honored at different cemeteries in Italy. Hearne is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at Florence American Cemetery, while Inglis is honored at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery. Hearne is also honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Birth

Oddly enough, Hearne’s enlistment data card (in his case, data recorded when he went on active duty after his Delaware National Guard unit was federalized) gave his year of birth as 1919 rather than 1920. The source of the error is unclear, since it could have been in National Guard records, a mistake on the card, or a scanning error when the card was digitized.

Differences between Night Fighter Training Program in November 1943 and February 1944

The program described in the February 1944 document was likely similar to the program Hearne attended in November 1943, with one major exception. Cffective December 1, 1943, after Hearne’s class, the first phase of the radio observer training program was taught at Army Air Forces Eastern Technical Training Command, Boca Raton Field, Florida, rather than with the 348th Night Fighter Squadron.

Unit

According to American Battle Monuments Commission records, Flight Officer Hearne’s unit was Headquarters Squadron, XII Fighter Command. That unit is engraved next to his name on the Tablets of the Missing at the Florence American Cemetery. If accurate, that would suggest that Hearne was a member of that headquarters squadron and merely attached to the 417th Night Fighter Squadron at the time of his death.

There is no doubt that the 417th Night Fighter Squadron was under XII Fighter Command, but there is no evidence in other sources that Hearne was anything but a full member of the 417th Night Fighter Squadron. His individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) listed his unit as the 417th Night Fighter Squadron. Similarly, his flight record listed the 417th Night Fighter Squadron as his assigned unit, not one he was attached for flying. The 417th Night Fighter Squadron morning report documenting that Hearne was missing stated that his prior status was duty, whereas if he had been attached, that would ordinarily have been mentioned at that time.

Arrival Date with 417th Night Fighter Squadron

The date that Flight Officer Hearne joined the 417th Night Fighter Squadron is unclear. In his book, Beaufighters in the Night, “Brick” Eisel suggested that both Hearne and Inglis joined the squadron on July 5, 1944:

Some of the replacements coming in included Lieutenant Harold Heinecke, R/O, and his pilot, Lieutenant Tom Hill. Russ Gaebler and Everett Packham, pilot and R/O, also arrived along with Second Lieutenant Robert Inglis, pilot, and replacement Flight Officer Ted Hearne, R/O. They took up their posts on 5 July.

In fact, Hearne’s flight records show that he joined the 417th Night Fighter Squadron after May 2, 1944, when he was still in California, and no later than June 17, 1944, when he participated in his first flight with the squadron on Corsica.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Flight Officer Hearne’s nephew, Gary L. Hearne, and to Jackie Foster of the 417th Night Fighters website, for contributing documents and photos. Thanks also go out to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research and to John Meir for archival records that were vital in reconstructing Hearne’s military career, and to Kennard R. Wiggins, Jr., for sharing the manuscript of his upcoming book, Delawareans at Their Best: The Evolution of the Delaware National Guard. Finally, thanks to Autumn Hendrickson, who told me about recently digitized U.S. Army, which allowed me to update this article with more specifics about Hearne’s career in the 198th Coast Artillery.

Bibliography

“3 Soldiers From State Die in Action.” Journal-Every Evening, August 7, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140093366/

“93 From 198th Are Promoted At Camp Upton.” Journal-Every Evening, January 21, 1941. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140094327/

Application for Headstone or Marker for Isaac John Hearne. January 3, 1962. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_1521003239_0451-02611

Application for Headstone or Marker for James A. Hearne. July 28, 1950. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_2421402106_0400-03633

Application for Headstone or Marker for John Thomas Hearne. March 5, 1974. Applications for Headstones and Markers, July 1, 1970 – September 30, 1985. Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/2375_12_01019-02040

Application for Headstone or Marker for Robert W. Inglis. March 31, 1977. Applications for Headstones and Markers, July 1, 1970 – September 30, 1985. Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/2375_02_01073-01573

“Army Awards Medals to 12 From State—6 Posthumously.” Journal-Every Evening, March 24, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140095033/

Award Cards, 1942–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/133384640?objectPage=877

“Bastia Borgo.” Abandoned Forgotten & Little Known Airfields in Europe website. https://www.forgottenairfields.com/airfield-bastia-borgo-1278.html

Certificate of Birth for James Andrew Hearne. August 18, 1927. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQM-Q4N9

Certificate of Birth for Marylin Aletha Hearne. Undated, c. August 17, 1929. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQM-QD3B

Clay, Steven E. U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919–1941, Volume 2. The Arms: Cavalry, Field Artillery, and Coast Artillery, 1919–41. Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16040coll3/id/197/rec/2

Eisel, Braxton. Beaufighters in the Night: 417 Night Fighter Squadron USAAF. Pen & Sword Aviation, 2007.

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRHM-QCZ

Hearne, Isaac J. Individual Military Service Record for Theodore Edward Hearne. Undated, c. 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/19092/rec/11

“Historical Data Night Fighter Squadrons AAF Tactical Center Orlando, Florida 1 Oct 1942 – 8 Feb 1944.” Reel A2670. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“History of Army Air Base Salinas, California Covering the Period From 1 April 1944, to 1 May 1944.” Reel B2495. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Theodore E. Hearne. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Gary L. Hearne.

Individual Flight Record for Theodore E. Hearne. May 1943 – July 1944. Individual Flight Records, 1911–1958. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller and John Mier.

“Inglis Killed Over Corsica.” Capital Journal, September 13, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140092243/

Jackson, Robert E., Jr. “417 NFS War Diary, dtd 5 June/44.” Reel A0801. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Jackson, Robert E., Jr. “Outline History of the 417 NI FTR SQ for the Period 1st July to 30th July, 1944.” August 1, 1944. Reel A0801. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Jackson, Robert E., Jr. “War Diary of 417 NI FTR SQ, Borgo A/D, Corsica, Month of July, 1944.” Reel A0801. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Jackson, Robert E., Jr. “War Diary, 417th Night Fighter Squadron, Period 1st to 30th June, 1944 (Incl).” Reel A0801. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“James A. Hearne.” Wilmington Morning News, July 22, 1950. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140785113/

Jauch, Ralph C. “A Brief Historical Summary.” Undated, c. 1946. Reel A0801. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Kin of 4 State Fliers to Get Medals Today.” Wilmington Morning News, April 6, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140642164/

McCray, C. Richard. “Missing Air Crew Report No. 7068.” July 23, 1944. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. The National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/91024482

McLees, R. C. “History of the 348 Night Fighter Squadron 481st Night Fighter Operational Training Group October 1942 – October 1943 November 1943.” Reel A0781. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Missing Fighter Pilot Reported Killed; Three Others Wounded.” Journal-Every Evening, September 14, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140093242/

“Monthly Personnel Roster July 31 1941 HQ Btry 1st Bn 198th Coast Arty.” July 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494_10.pdf

“Monthly Roster Hq Btry & CT, 1st Bn 198th CA Camp Upton, N. Y.” October 31, 1940. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494_10.pdf

Morning reports for 417th Night Fighter Squadron. July 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

“Mother Receives Son’s Flying Cross.” Journal-Every Evening, April 7, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140642256/

“Pay Roll of Headquarters Battery First Battalion, 198th C.A. (AA) Base Bobcat For month of November, 1942.” November 30, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494_10.pdf

“Proposed Citation for 417th Night Fighter Squadron.” May 16, 1945. Reel A0801. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Serving Uncle Sam.” Capital Journal, August 6, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140091822/

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-MLG

“Special Roster Headquarters and Headquarters Battery First Battalion, 198th C.A.” October 15, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0494_10.pdf

“Squadron History 348th Night Fighter Squadron 481st Night Fighter Operational Training Group Army Air Forces Tactical Air Center Orlando, Florida December 1–31, 1943.” Reel A0780. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Squadron History 348th Night Fighter Squadron 481st Night Fighter Operational Training Group Salinas Army Air Base Salinas, California January 1–31, 1944.” Reel A0781. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Squadron History of the 417th Night Fighter Squadron.” November 3, 1943. Reel A0801. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Suggested Night Fighter Training for Pilots and Radar Observers.” February 16, 1944. Reel A0781. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Theodore Edward Hearne.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56364110/theodore-edward-hearne

“Unit Historical Data Sheet 348th Night Fighter Squadron of 481st Night Fighter Operational Training Group.” Reel A0781. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Wiggins, Kennard R., Jr. Delawareans at Their Best: The Evolution of the Delaware National Guard. Unpublished manuscript, 2023. Courtesy of Kennard R. Wiggins, Jr.

“With the Service Men And The Auxiliaries.” Wilmington Morning News, February 11, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140092851/

“With the Service Men And The Auxiliaries.” Wilmington Morning News, February 18, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140094599/

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=hearne%23theodore&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=1897771, https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=20938683&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=2112999

Last updated on June 17, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.

Thank you Lowell, well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person