| Home State | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware | Textile worker at DuPont’s nylon factory |

| Branch | Service Number |

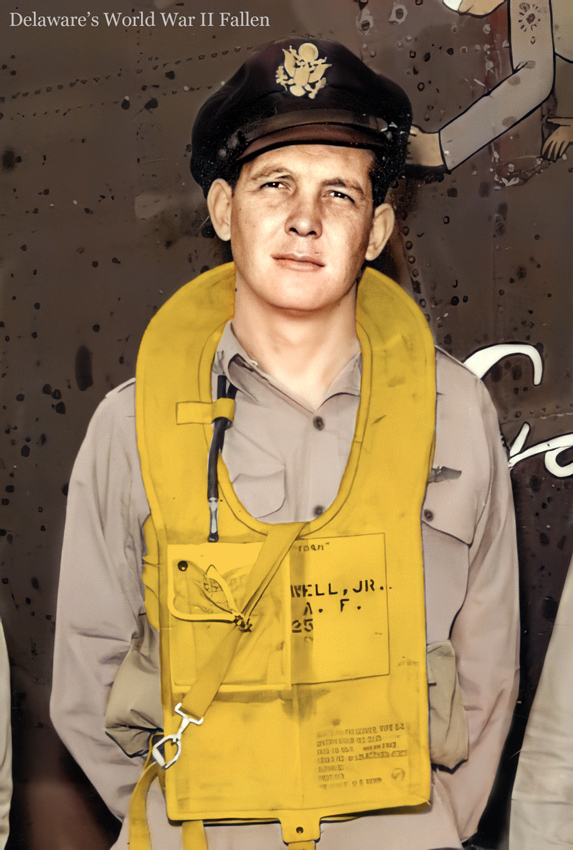

| U.S. Army Air Forces | Enlisted 20264329 / Flight Officer T-60328 / Officer O-534947 |

| Theater | Unit |

| American, Pacific | 38th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 30th Bombardment Group (Heavy) |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Air Medal | Antisubmarine campaign, Central Pacific |

Early Life & Family

George McCullen Johnson was born near Seaford, Delaware, on May 8, 1920. He was the son of James Everett Johnson (a farmer, 1897–1927) and Mary Alice Johnson (née Wheatley, later Tull, 1897–1984). Johnson’s parents had married in Seaford on February 24, 1915. Johnson had an older sister, Edna Gertrude Johnson (later Starr, 1916–1989) and a younger sister, Mary Evelyn Johnson (later Christopher, 1922–2007). His mother and younger sister went by their middle names. Shortly before Johnson was born, his family was recorded on the 1920 census, living on a farm along the Woodland and Reliance Road. Johnson was just seven when his father died.

Johnson was recorded on the census in April 1930 living on Willow Street in Seaford with his mother, now working at a school cafeteria, and two sisters. He played football at Seaford High School, graduating in 1938. The next census in April 1940 recorded Johnson living in Seaford with his mother, now the manager of the Seaford High School cafeteria, and older sister. His occupation was recorded as “Topper” at a hosiery mill—the DuPont Company’s nylon factory, which had opened in Seaford the previous year. Similarly, his future wife reported his civilian occupation as textile operator in a statement to the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission. Johnson’s mother later worked at the factory cafeteria.

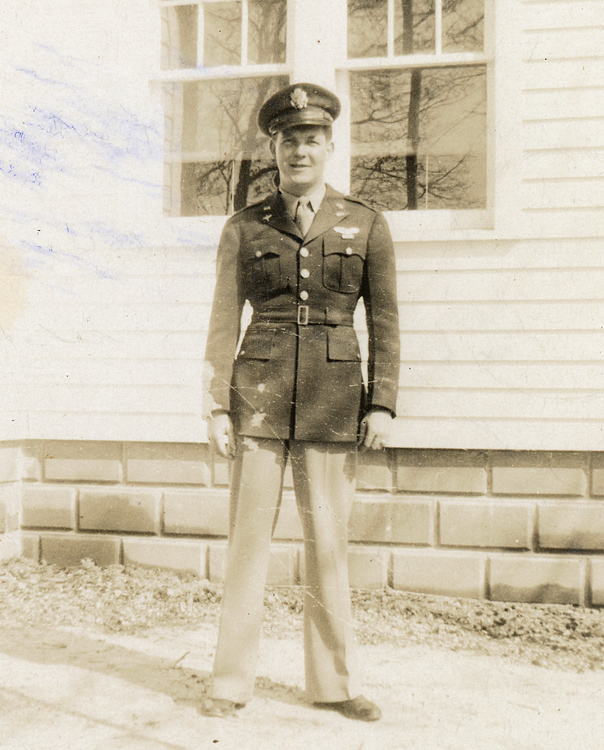

Johnson’s military paperwork described him as standing five feet, 11 inches tall and weighing 143 lbs., with brown hair and eyes.

National Guard Service

According to the State of Delaware Individual Military Service Record filled out by his wife during or just after the war, Johnson joined the Delaware National Guard in 1935. He would have been no more than 15 years old at the time.

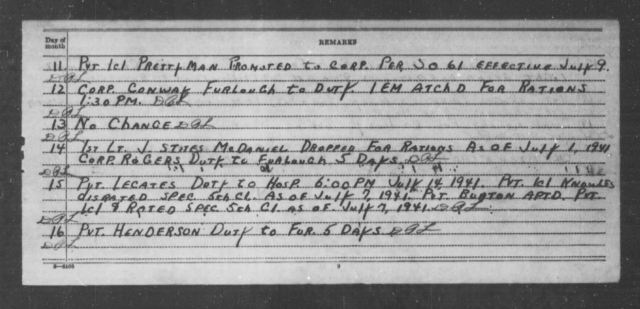

Articles in Journal-Every Evening provide glimpses of his National Guard career. As of February 25, 1937, when he was awarded a bronze bar for one year of perfect attendance (in lieu of a second bronze medal), Private Johnson was a member of Battery “A,” 261st Coast Artillery Battalion (Harbor Defense), then based at Laurel Armory, which was equipped with 155 mm guns. On March 23, 1938, when he received another bronze bar, he was a corporal in the same unit. A roster stated he reenlisted on October 2, 1938.

Johnson had been promoted to sergeant by January 27, 1941, when the 261st Coast Artillery Battalion entered federal service. Battery “A” moved to Fort DuPont, Delaware, on February 4, 1941. They spent the next few months doing both infantry and artillery training. The guardsmen were supplemented with draftees, who they also had to train. The battery participated in a Memorial Day parade in Wilmington, Delaware, on May 30, 1941.

On June 5, 1941, Johnson and his comrades moved to Camp Henlopen, Delaware, an installation subsequently known as Fort Miles beginning on August 14, 1941.

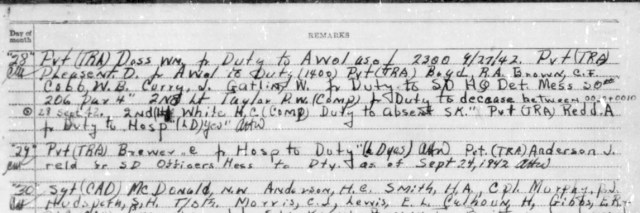

A July 1941 roster, the earliest to record duties, listed Sergeant Johnson’s as 651, platoon sergeant. On October 17, 1941, Johnson was reduced to the grade of private, though his duty code remained the same.

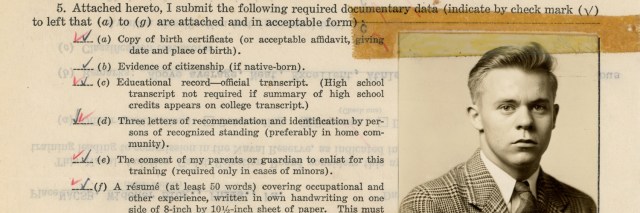

On November 5, 1941, after passing a classification test to qualify for pilot training, Johnson requested a discharge from the Coast Artillery Corps to reenlist in the Air Corps, the combat arm to which most members of the new U.S. Army Air Forces belonged. A November 1941 roster, the first to list military occupational specialty, listed Private Johnson’s M.O.S. as 725, plotter, though his duty code remained 651. He transferred out of the unit on March 27, 1942, to begin his flight training.

Flight Training

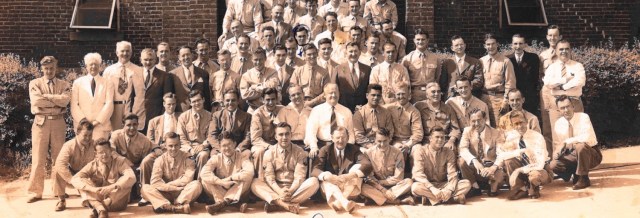

Johnson had to complete four phases of aviation training to become a pilot in the U.S. Army Air Forces: Johnson had to complete four phases of aviation training to become a pilot in the U.S. Army Air Forces: preflight, primary pilot training, basic pilot training, and advanced pilot training.

On March 28, 1942, Johnson caught a train in Wilmington, arriving one day later at Maxwell Field, Alabama. Johnson was assigned to Class 42-K and began preflight training on March 30, 1942. Preflight was purely ground school, featuring both physical training and academic subjects, such as physics and geometry.

Johnson completed his preflight training on May 28, 1942, and around June 1, 1942, he moved to Decatur, Alabama, to begin his primary pilot training. Primary involved more advanced academics (with topics including theory of flight and aerodynamics) as well as actual flight training.

Johnson’s weekly letters to his mother, written in immaculate cursive, chronicle his training, movements, and thoughts. Johnson regularly closed his letters with well wishes to his sisters, his future stepfather, Ed Tull, and his dog, Frisky. He wrote in a June 7, 1942, letter:

I took my first airplane ride yesterday [and it] sure was fun. When you are away up there everything looks small and the fields are all different colors and shapes. It is just like looking at a quilt only more pretty. I like it much more than I even thought I would. […] The studies are a lot harder than they were at Maxwell and you can’t fail even one subject. Your flying has to be perfect too or you fail. It is getting harder all the time and the other two schools are harder yet.

Johnson soloed in a training aircraft for the first time on June 26, 1942. Two days later, he wrote to his mother: “Soloing means taking a plane up by yourself. I did alright and landed it okay. It is a lot more fun when you are up by yourself.”

By July 26, 1942, Johnson had completed 43 hours of flight time with 17 more hours required to graduate from primary. In a letter to his mother that day, Johnson told her that he had no regrets about trading his post at Fort Miles for flight training: “I am a lot better off here. I am getting a better education and I am in better physical shape and what I am doing has a future.”

Johnson wrote to his mother on August 2, 1942, that he had passed the last of the tests in both ground school and flying to pass primary, adding that around 25–30% of his classmates had washed out during the first two phases of training.

After finishing primary, he and some classmates visited Memphis, Tennessee, and then hitchhiked to their next station in Blytheville, Arkansas, arriving around August 5, 1942. During basic pilot training, Johnson continued to accumulate flight time, some of it at night. He also trained in flying on instruments alone. He wrote on October 4, 1942:

Well I am all finished Basic School. I had my last flight last night. We had a two hundred and fifty mile cross country flight. It feels good to get through. All we have this week is ground school. I am going to Lawrenceville, Illinois for Advanced School. It is a twin engine School where they train you to fly bombers or planes that have more than one engine. It is a new school and we will be the first class to go there so no one knows what it is like.

Johnson arrived at George Field, Illinois, on October 10, 1942. He wrote his mother the following day, reflecting on his career in the Army:

I think that it is the best thing that happened to me especially the Air Corp. […] We all talk about how lucky that we are to get this far and to have this opportunity. At the end of two more months the govt. will have spen[t] over twenty-five thousand dollars on each of us for this training and I know that I could have never been able to get it in civilian life. Also it will enable me to get a good job in civilian life when the war is over.

Johnson began his advanced pilot training on October 12, 1942. Bad weather temporary slowed the pace of his training, but Johnson wrote on November 16, 1942, that he had made up for it:

One day I flew seven hours & forty minutes. That is a long time and usually you aren’t allowed to fly more than five hours a day, but we were so far behind that we had to do it to catch up. […] I have finished all my night flying. […] I have about thirty more hours to go and I will be finished.

Upon graduation from advanced pilot training on December 13, 1942, Johnson was appointed to the grade of flight officer.

Antisubmarine Campaign

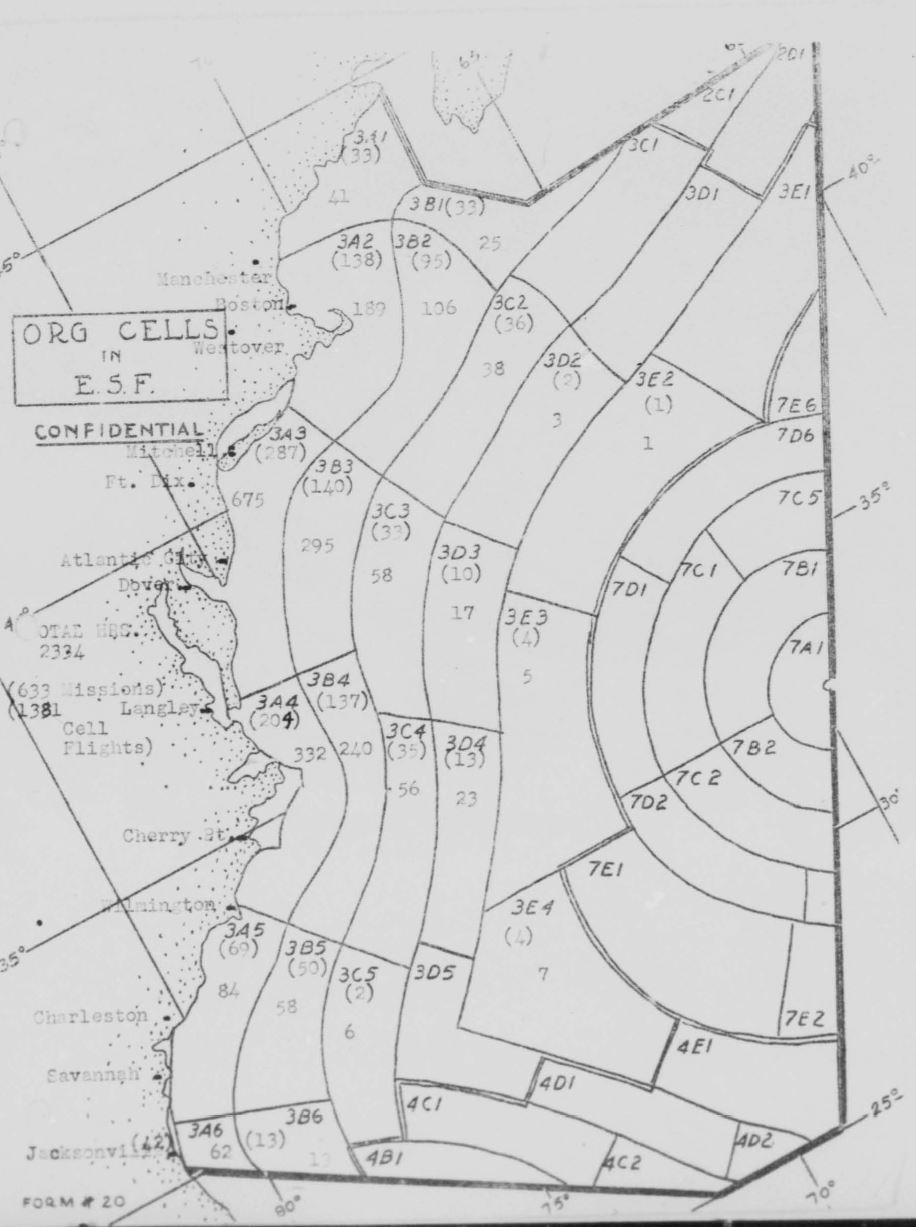

Flight Officer Johnson arrived at Grenier Field, New Hampshire (now Manchester-Boston Regional Airport), on December 15, 1942, and joined the 13th Antisubmarine Squadron, 25th Antisubmarine Wing. The 25th Antisubmarine Wing patrolled the Eastern Seaboard for U-boats and escorted convoys in coastal waters. The wing was barely a month old and was not yet operating very smoothly. Johnson was transferred several times to different squadrons within the wing during the next few months. His first squadron had too few planes, and on January 5, 1943, Johnson and several other pilots transferred to the 18th Antisubmarine Squadron at Langley Field, Virginia. An operational training unit, that squadron was similarly disorganized, as Flight Officer Johnson explained in a January 10, 1943, letter:

They told us that we were coming down here for a month to learn how to fly four engine ships. When we get here they say that they haven’t enough ships for their own men and that all we will get is ground instruction on them. […] It seems this Anti-Sub is a new command and just don’t have the equipment.

Around February 1, 1943, Flight Officer Johnson transferred to the 6th Antisubmarine Squadron at Westover Field, Massachusetts. His stay there was also short. He wrote to his mother on February 27, 1942:

I will be transferred with the fellows that came up here with me within a month. The Sixth Anti-Sub is going overseas shortly but us new pilots don’t have enough experience so we don’t get to go along. Tough luck because I would love to go.

On March 9, 1943, Flight Officer Johnson joined the 11th Antisubmarine Squadron at Fort Dix Army Air Base (later McGuire Air Force Base and today part of Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst) in New Jersey. Then, on April 20, 1943, Johnson transferred to the 3rd Antisubmarine Squadron, also stationed at Fort Dix Army Air Base. In a letter to his mother the following day, Johnson explained:

They are going to Langley Field for four engine training and they were short of men. Mac [Glenn Linwood McCann, his future best man] & I & four other pilots were sent over. It is a break for us because things were slow in the 11th and the planes only twin eng. When I finish at Langley this time I will be qualified to fly in the biggest bomber that the Air Force uses.

3rd Antisubmarine Squadron records show that by the end of April, Johnson had 225 hours of flying time under his belt, but only 28.1 hours flying multiengine aircraft. The 3rd Antisubmarine Squadron was equipped with North American B-25 Mitchells when Johnson joined, but as his letter mentioned, the unit began training with the Consolidated B-24 Liberator at Langley Field that spring. Johnson returned to Fort Dix Army Air Base around May 22, 1943. The first B-24s reached the unit in late May or early June 1943.

By the end of August 1943, Johnson had accumulated just over 424 hours of flight time, including 221¼ hours in multiengine aircraft. He never saw—much less attacked—a single enemy submarine. As it turned out, the U-boat threat to the Eastern Seaboard had dropped drastically even before the 25th Antisubmarine Wing had been organized. During the summer of 1942, the Germans decided to redeploy their U-boats to the mid-Atlantic, out of range of Allied land-based aircraft. Indeed, from November 1942 through June 1943, the entire 25th Antisubmarine Wing recorded just two confirmed submarine sightings despite logging thousands of hours of patrol and escort missions each month.

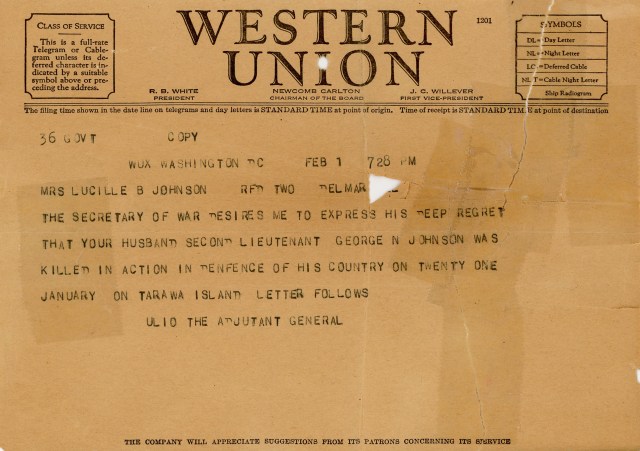

Marriage

Flight Officer Johnson married Lucille Butler (1920–1987) in New Jersey on June 6, 1943. His bride was from Federalsburg, Maryland, just over the state line from where Johnson had grown up, and presumably they met before the war. Butler was living in Baltimore, Maryland, and working at the nearby Martin aircraft factory in Middle River while Johnson was in flight school. They began corresponding and apparently, they began dating around March 1943 when Johnson’s assignment at Fort Dix made it possible for the couple to meet in Baltimore and Trenton. Johnson announced their engagement to his family in a letter dated May 11, 1943. A June 18, 1943, article in the Wilmington Morning News reported:

Mrs. Johnson was formerly associated with the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Company and is the daughter of the late Mr. and Mrs. Bruce Butler of Federalsburg. Flight Officer Johnson is attached to Anti-Submarine Patrol of the Army Air Forces, and is the son of Mrs. Edward B. Tull.

After a brief wedding trip and a visit to relatives, the couple have returned to the base where Flight Officer Johnson is attached.

Correspondence indicates that they visited Johnson’s family in Wilmington and Sussex County after the wedding.

During the summer of 1943, the U.S. Navy took over antisubmarine operations on the Atlantic Seaboard. As a result, on September 15, 1943, the 3rd Antisubmarine Squadron was ordered west to March Field, California. Johnson obtained permission to make the journey separately from the rest of the unit and take leave until September 30, 1943.

Johnson and his wife departed Trenton on September 16, 1943, arriving the following day in Kansas City, Missouri. Johnson wrote to his mother on September 18, 1943, stating that “Tonight we plan to catch a train at nine thirty and arrive in Albuquerque, New Mexico Sunday [tomorrow] night about eleven o’clock.”

The couple reached Grand Canyon National Park on the afternoon of September 20, 1943. In a letter dated September 22, 1943, Johnson wrote:

Mom, I am not fooling, this is the most beautiful place that I have ever seen. I only wish that you could see it for I don’t thin[k] that there is anything in all the world that can compare with it. I will send some pictures to you of the Canyon but this is the one place where the picture cards don’t do justice to the scenery. They have a mule trip to the bottom of the canyon but I don’t think that I will go on it this time as we are planning to come back here again sometime.

The Johnsons arrived in California on September 23, 1943, renting a room in a house at 4367 Jurupa Avenue in Riverside—close to his new station at March Field. Johnson was promoted to 2nd lieutenant on September 29, 1943. He learned that he would be going overseas soon—to Hawaii, rumor had it.

Briefly, just prior to his departure, Lucille thought she might be pregnant. In a letter dated October 7, 1943, Lucille wrote to Johnson’s mother: “George is so tickled that he hardly knows what to do. And he is sick because he can’t be with me.”

As it turned out, she was not. Although he had written that he was looking forward to being a father, Lieutenant Johnson put a positive face on the disappointing news in a November 25, 1943, letter to his mother: “I am not sorry that she isn’t pregnant. Really I am glad for it wasn’t fair to her.”

Johnson’s religious preference was recorded as Protestant on his military paperwork. Though it seems that he was not particularly religious, his wife apparently influenced him in that area. Once overseas, he wrote his mother in a letter dated December 13, 1943: “Guess what? Lucille made me start saying my prayers before I left and I have been keeping it up. Surprised?”

Service in the Pacific Theater

On September 21, 1943, the 3rd Antisubmarine Squadron was redesignated as the 819th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy) and was assigned to the 30th Bombardment Group (Heavy), which was earmarked for the U.S. Seventh Air Force in the Pacific Theater.

The 819th Bomb Squadron arrived at Camp Stoneman, California, on October 5, 1943, and shipped out from the San Francisco Port of Embarkation about a week later, on October 13, 1943. After disembarking at Port Allen on Kauai on October 22, 1943, the unit was briefly stationed at nearby Barking Sands before moving to Wheeler Field on Oahu the following month. Early missions included sea searches and ferrying aircraft to bases in the Central Pacific.

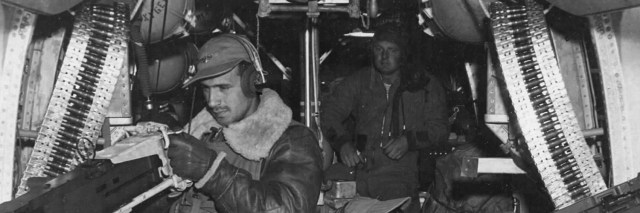

By January 1944, Johnson was copilot in 1st Lieutenant Howard T. Lurcott’s B-24 crew. Lurcott (1917–1944) had completed flight training at Kelly Field, Texas, in October 1942 and had joined the 3rd Antisubmarine Squadron by that December. Extant records do not reveal when the two men began flying together. Circumstantial evidence indicates that the two men ferried a B-24 from Hawaii to the Central Pacific in early December 1943, but they conceivably could have been in the same crew for months before that.

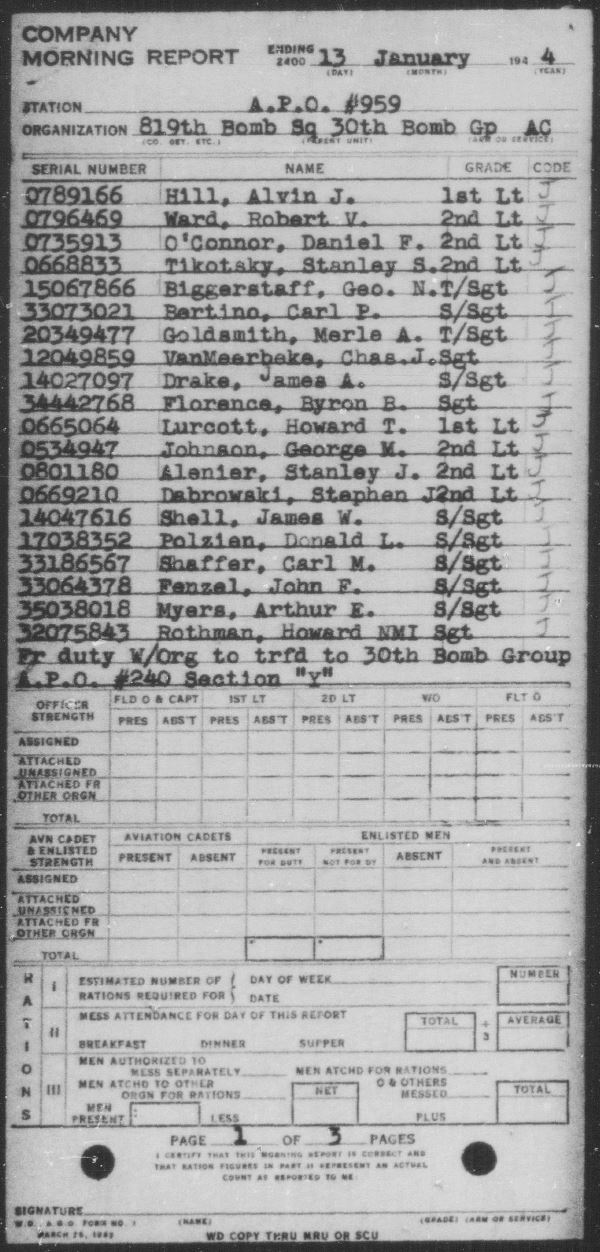

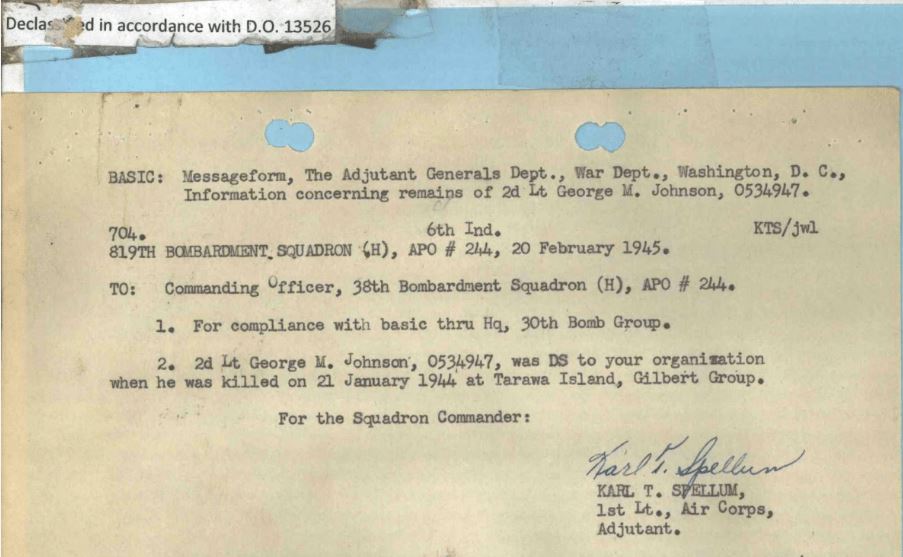

On January 13, 1944, 2nd Lieutenant Johnson and the rest of the Lurcott crew moved to the 38th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), another squadron in the 30th Bomb Group. (Contemporary documents are inconsistent on whether Johnson and his crew were transferred to, attached to, or on detached service with the 38th.) The 38th Bomb Squadron—then based on Nanumea in the Ellice Islands (present-day Tuvalu)—primarily targeted far flung Japanese outposts in the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. On January 19, 1943, Lieutenant Johnson sat down to write what proved to be his last letter to his mother:

Dear Mother,

How is everything at home? I hope that you are all well. I am and very comfortable too. I think that by now you have learned that my APO [Army Post Office] has changed again. I am now on a [coral] island south of the equator. There is very little that I can tell you because of censorship rules but I will tell you what I can.

The island isn’t very large but it is very pretty because there are a lot of palm trees and tropical growth. There are quite a few natives and while they are hardly like the movies show them they are very interesting. The days are almost [unbearably] hot but the evenings are cool and comfortable. Everyone lives in tents and I have built a floor in mine and I am fixed up very nice. It really isn’t very bad at all and in fact much better than I had cause to expect.

I have a little good news too. They have set up a system for returning to the States. Naturally it isn’t right away but I think that I am safe in saying that it will be before Xmas. And to tell the truth that is much sooner than I originally believed to get home.

Tell Evelyn that I am sorry that I didn’t get to send her a birthday card, but congratulations to her just the same. I suppose that your mail is getting there as slow as Lucille’s. I can’t understand it. I have wrote to Lou every day I have been here and to you twice a week. I think Lou thinks I am not writing. You may too but that isn’t the case but I do think that my letters will be a little slower now than before. You will just have to have patience.

I must close now for I can think of nothing else to say. Give my love to Edna, Evelyn, Ed and Frisky but most of all to you.

Your loving Son

George

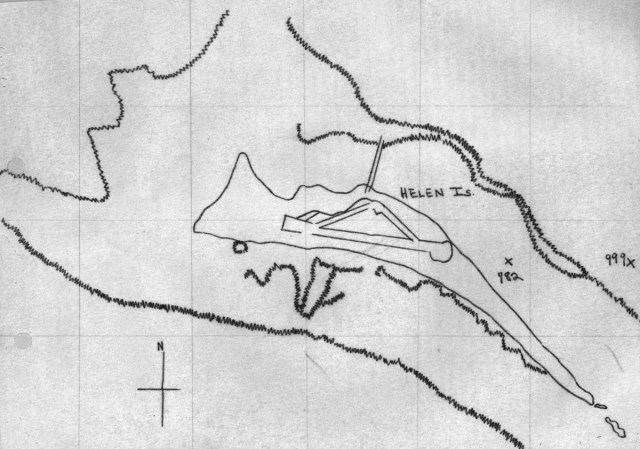

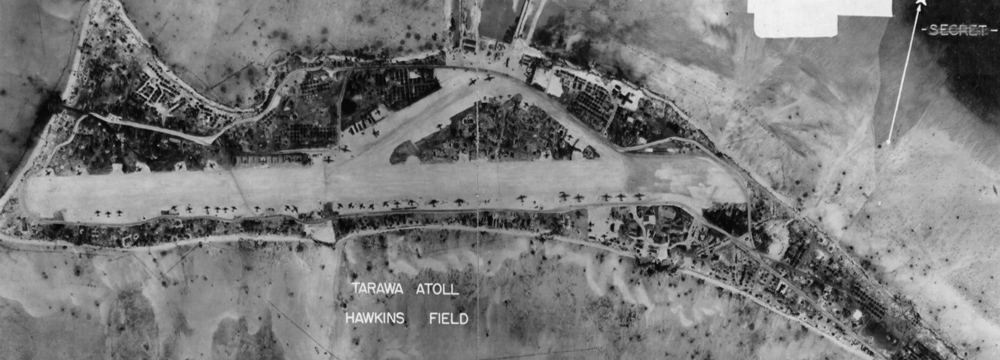

The following day, January 20, 1944, the 38th Bomb Squadron temporarily moved to Hawkins Field on Betio, in the Tarawa Atoll of the Gilbert Islands (present day Kiribati). American forces had taken Tarawa the previous November after vicious fighting.

Lurcott and Johnson’s crew was one of nine assigned to a night mission against the Japanese airfield on Roi Island in the Kwajalein Atoll, flying a B-24J (serial number 42-72999). Notwithstanding numerous patrols on the East Coast and Hawaii, it was their first combat mission. Most accounts list the date of the mission as January 21, 1944. Curiously, some documents place the mission as beginning just after midnight local time on January 22, 1944. (See the Notes section for further details.)

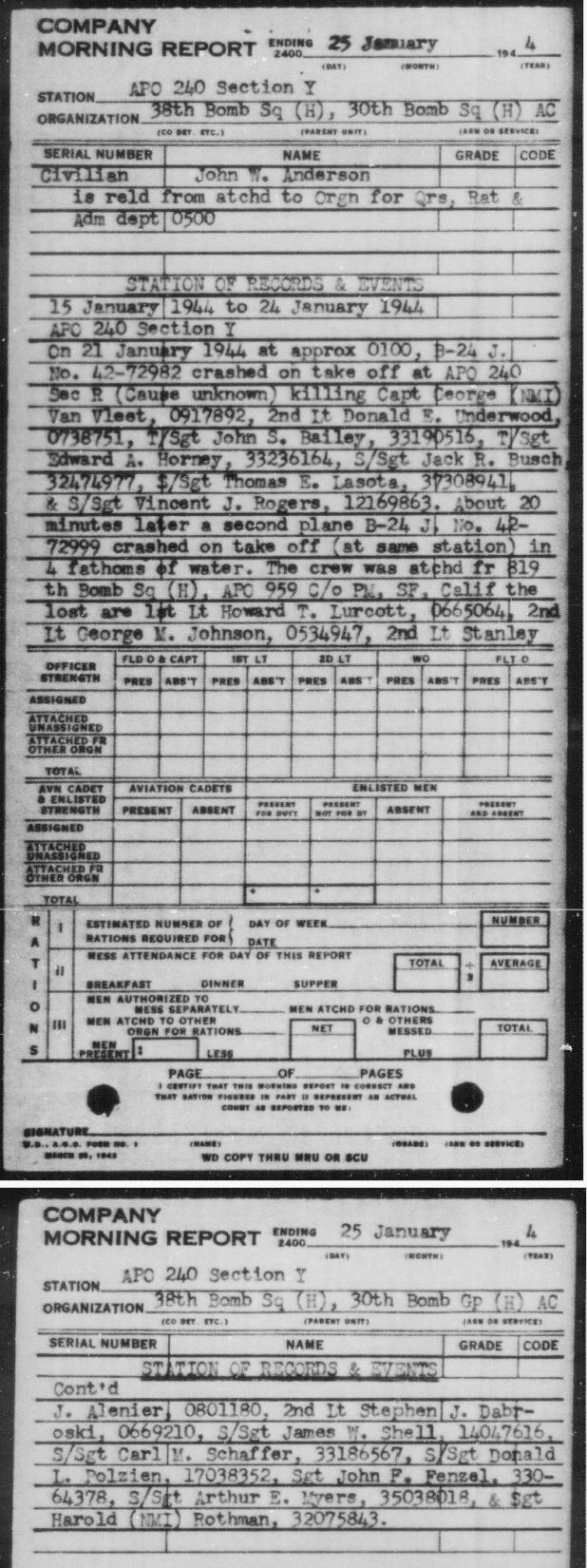

As the mission began, a B-24J (42-72982) failed to gain altitude after takeoff and crashed, killing seven men and injuring three. Minutes later, Lieutenants Lurcott and Johnson began their takeoff roll.

According to a memo, dated January 23, 1944, and written by 1st Lieutenant William G. Volkman, Jr., assistant S-2 (intelligence officer) for the 30th Bomb Group:

[42-72999] took off seventeen (17) minutes after Airplane B-24J, No. 42-72982 which had also crashed. The plane made a very normal take-off and had started to climb toward the East but the engines did not sound as though they were developing power. The airplane reached an altitude between 250 and 300 feet and then started to settle slowly. The plane blew up in two distinct, violent explosions upon contact with the water […] approximately 3 miles from the end of the runway, with the plane settling to the bottom of the lagoon in a depth of 24 feet of water.

All 10 men aboard Lurcott and Johnson’s B-24 were killed in the crash. A copy of Missing Air Crew Report No. 2629 stated that the crash was “Believed to have been caused by water in gas.”

Lieutenant Johnson was buried as an unknown (later given the identifier X-2), along with other members both B-24 crews in the Main Marine Cemetery on Tarawa. Unfortunately, many years would pass before his remains returned home.

Recovery & Identification

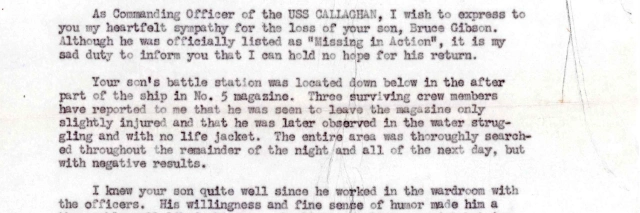

In a letter dated April 26, 1944, the 38th Bomb Squadron commander, Major Thomas E. Thompson, wrote to Johnson’s mother:

At this time Mrs Tull, we are still unable to say definitely if George’s body was recovered. The airplane in which he was flying as co-pilot crashed immediately after take-off and a very severe explosion followed. Three of the crew, including the pilot, Lieut Howard T. Lurcott, were identified. Two bodies were recovered but could not be identified, however fingerprints taken are under observation and we shall let you know if they prove to be your sons.

The fingerprints, if they were indeed taken, do not appear to have made survived in the historic record, and there is no mention of them in available official documentation. Later in 1944, men of the Naval Construction Battalions (Seabees) modified the Main Marine Cemetery. In “Historical Report: 2d Lt George M. JOHNSON,” Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (D.P.A.A.) historian Hannah Metheny wrote that

when the Seabees shifted the cemetery markers to accommodate the new construction, they did not shift the graves. As a result, the crosses no longer corresponded with the original grave site. […] Marines whose remains had not been recovered, who were buried at sea, or who were buried elsewhere on the island, were often given a memorial cross in one of the larger cemeteries. As a result, the names on the crosses no longer corresponded with the names of those originally believed to be buried in the cemetery. The Seabee’s beautification efforts included the Main Marine Cemetery, now renamed Cemetery 33, which the Seabees rotated and expanded significantly. When the Seabees were finished, instead of 153 graves (the original number of individuals believed to be buried in the cemetery), there were almost 400 white crosses in Cemetery 33.

After the war, in 1946, the U.S. Army’s 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company began exhuming Cemetery 33. Their intention was to consolidate the bodies buried at several cemeteries into one large one, the Lone Palm Cemetery. As a result of the Seabees’ “beautification” project, the 604th struggled to match burial records with the bodies being recovered. The 604th recovered most of Lieutenant Johnson’s remains during the 1946 expedition but incorrectly identified them as belonging to Staff Sergeant Jack R. Busch, Jr. (1920–1944), one of the men killed during the first B-24 crash. In fact, Staff Sergeant Busch had been buried next to Lieutenant Johnson’s body (X-2), but his body was not discovered until decades later. When the 604th’s men exhumed Johnson, they did not find any identification on his body, but they did find Busch’s marker on the surface. Unfortunately, as Metheny explained in her report:

The 604th GRC based this identification solely on the proximity of S Sgt Busch’s memorial grave marker. As previously mentioned, the memorial markers did not accurately reflect the identities of those buried nearby. The 604th GRC only used markers to make identifications five times before discovering it was unreliable and abandoning the practice altogether; despite this, they never reviewed the initial identifications made using this method.

Most of Johnson’s body—some of his remains in Cemetery 33 would not be discovered for decades to come—was reburied in Lone Palm Cemetery on March 18, 1946, this time with plates and a bottle identifying him as Busch. Because his identity had supposedly been established, nobody attempted to perform a forensic analysis, which would have been done on an unidentified body. That was unfortunate, because even contemporary forensic science stood a fair chance of correctly identifying Lieutenant Johnson. The fact that he was buried in a casket distinguished him from most burials conducted during and immediately after the Battle of Tarawa, where Marines were buried in ponchos. That meant that there were only a handful of potential candidates. Even though D.N.A. testing did not exist in 1946, anthropological clues and dental records may have been enough to identify Lieutenant Johnson.

Authorities decided against maintaining Lone Palm as a permanent U.S. military cemetery. As a result, Johnson’s body was disinterred on December 16, 1946. He was reinterred at the U.S. Army Mausoleum at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, on January 13, 1947. That year, Staff Sergeant Busch’s father requested that his son’s remains be repatriated to the United States. Johnson’s body was disinterred for a third time on October 14, 1947, and reburied in Acacia Park Cemetery in North Tonawanda, New York, in early March 1948.

Around that same time, the Quartermaster Corps Memorial Division attempted to determine why the Army had been unable to locate remains for many victims of the two B-24 crashes, despite the existence of burial reports from 1944. According to a memo dated March 4, 1948, the officer who signed those reports

stated that the original burial reports were prepared prior to his arrival and that he was told to forward them to headquarters. After an investigation, conducted by himself without much success, he believes that these reports were prepared for which no bodies were recovered, due to the crash at sea.

On March 20, 1949, guided by locals who had witnessed the crash five years earlier, a diver located the wreckage of B-24J 42-72999 in about 30 feet of water. He attempted to recover remains from the sunken plane, without success.

The following year, Captain Joseph F. Vogl, Quartermaster Corps Repatriation Branch, again investigated the discrepancies pertaining to the recovery of bodies from the two B-24 crashes. He interviewed the 38th Bomb Squadron’s medical and commanding officers, who stated that they believed no remains had been recovered from Johnson’s B-24. Six years earlier, Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Thompson had correctly informed Johnson’s mother that five bodies had been recovered from Johnson’s B-24. With the passage of time, he told a very different story. Captain Vogl summarized his May 8, 1950, interview in a memo:

With respect to decedents from plane 72999 Mr. Thompson could give no information on the recovery of any of the remains. He definitely said that he did not believe that any of the remains were recoverable. I told Mr. Thompson that we had a burial report on Lurcott, Dabrowski and Myers but that Lurcott’s remains were missing at the time of our exhumation operations. […] In answering letters from Next of Kin, Mr. Thompson could not definitely recall what he wrote them but was quite certain that he made no mention of any burial.

Authorities concluded that Lieutenant Johnson’s body was non-recoverable. Captain Vogl reported that decision to Johnson’s mother and widow in letters dated May 22, 1950. Thus, a sequence of circumstances and errors led to an unfortunate outcome. The failure to identify Johnson from fingerprints or other methods in 1944, the “beautification” project by the Seabees which wrecked the original grave markers, the 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company’s failure to locate Staff Sergeant Busch’s body and their erroneous identification of Johnson as Busch, the fact that two officers forgot that five men from 42-72999 had been recovered and buried, and the decision by the Quartermaster Corps Memorial Division to trust these erroneous memories rather than contemporary records…all of these events together denied the Johnson family closure for many years.

Lieutenant Johnson was posthumously awarded the Air Medal on December 15, 1953.

Johnson’s mother placed a cenotaph at Odd Fellows Cemetery in Seaford, where his father was buried. His mother, younger sister, and widow were also buried there after their deaths. Johnson’s name was honored on at the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii, on a plaque of DuPont employees killed during the war displayed at the factory in Seaford, and at Veteran’s Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

It was over half a century later before there was a break in the case. As summarized by the D.P.A.A.:

In 2017, History Flight, Inc., a non-profit organization […] recovered several coffin burials from Cemetery 33. These remains were sent to the DPAA Laboratory at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, for identification.

In April 2019, DPAA identified a set of remains as U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Jack R. Busch, Jr. He had reportedly been accounted for in 1946 and buried near Niagara, New York. Permission was granted by Busch’s family to exhume the remains in New York for testing.

History Flight also recovered a portion of Johnson’s remains that the 604th had missed back in 1946. Based on D.N.A. testing, dental records, and an anthropological analysis, forensics experts officially concluded on December 12, 2019, that the body was Lieutenant Johnson’s. The D.P.A.A. announced the results on March 18, 2020. Originally, Lieutenant Johnson’s funeral was scheduled for his 100th birthday on May 8, 2020, but it was postponed to October 2, 2021, due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

On September 28, 2021, Lieutenant Johnson’s nieces, Judi Thoroughgood and Janet De Cristofaro, were on hand when his casket arrived at Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport in Maryland aboard an American Airlines flight.

On October 2, 2021, the cenotaph that Johnson’s mother placed in the cemetery so many years ago at long last became the headstone for his final resting place.

Crew of B-24J 42-72999

The following list was adopted from Missing Air Crew Report No. 2629 with grade, name, service number, and position:

1st Lieutenant Howard T. Lurcott, O-665064 (pilot)

2nd Lieutenant George M. Johnson, O-534947 (copilot)

2nd Lieutenant Stanley J. Alenier, O-801180 (navigator)

2nd Lieutenant Stephen J. Dabrowski, O-669210 (bombardier)

Staff Sergeant James W. Shell, 14047616 (assistant engineer/gunner)

Staff Sergeant Carl M. Shaffer, 33186567 (radio operator/gunner)

Staff Sergeant Donald L. Polzien, 17038352 (flight engineer/gunner)

Sergeant John F. Fenzel, 33064378 (assistant radio operator/gunner)

Staff Sergeant Arthur E. Myers, 35038018 (armorer/gunner)

Sergeant Howard Rothman, 32075843 (radar operator/gunner)

Notes

Middle Name

Curiously, Johnson’s birth certificate listed him as George E. Johnson. According to his niece, Johnson’s middle name was originally supposed to be Everett, the same as his father’s middle name. That birth certificate is the only known document to give E. as a middle initial, but multiple documents—including his baptism certificate, high school diploma, advanced flying school diploma, a 13th Antisubmarine Squadron roster, and his wife’s statement—recorded his middle name as McCullen.

National Guard Career

Family-supplied information on the State of Delaware individual military service record forms submitted to the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission provide invaluable insight into the careers of Delaware’s fallen soldiers, especially those whose personnel files were destroyed or unavailable. However, I have found that many include errors, so I am wary of relying on them for facts that cannot be verified through other sources. Despite that caveat, Lucille Johnson’s statement does appear to be a generally accurate summary of Lieutenant Johnson’s career. Some dates pertaining to his pilot training differ by a few days from Johnson’s letters; this might be simply a discrepancy between when he arrived at a particular training facility and when the training began. Also, some sources indicate that Battery “A,” 261st Coast Artillery Battalion moved to Fort Miles in early June 1941 rather than May as Lucille Johnson wrote.

Although it seems remarkable that Johnson joined the Delaware National Guard in 1935—when he was no more than 15 years old—his wife’s statement is supported by circumstantial evidence. The Delaware National Guard awarded a bronze medal for one year of perfect attendance, a bronze bar for subsequent years, and then a silver medal at five years. These decorations should not be confused with the U.S. Army’s Bronze Star or Silver Star Medals. Private Johnson received the bronze medal in 1936 and a bronze bar on February 25, 1937, which indicates that his service had indeed begun in 1935. Furthermore, his enlistment data card from 1941 (when he entered federal service), though garbled, does indicate a year of birth of 1917 rather than 1920—consistent with Johnson having added three years to his age.

Oddly, Johnson continued to be listed in Battery “A” rosters through August 1942, despite having begun his flight training that March.

Demotion

Johnson was reduced to the grade of private, apparently for going absent without leave (A.W.O.L.) while he was stationed at Fort Miles. Later, in a February 4, 1943, letter written after he had become a pilot, Johnson mentioned that he had passed up an opportunity to visit Seaford when a training assignment in Virginia ended early because permission didn’t arrive in time from his unit up in Massachusetts: “I wanted to go home so bad but I was afraid to go A.W.O.L. because they are awful hard on officers for that. Also I got in trouble at Miles for that so I wasn’t taking any chances.”

Discharge and Reenlistment

During World War II, U.S. Army Air Forces were a component of the U.S. Army rather than a separate branch. The reason he had to request a discharge to reenlist in the Air Corps was a regulation (A.R. 615-150) that allowed enlisted men to become aviation students (a similar program to aviation cadets). Men with over one year in their enlistment terms could simply transfer, while men with less than one year left in their commitments had to resign and reenlist for three more years.

Johnson’s Mother & Stepbrother

Years after the death of Lieutenant Johnson’s father, Johnson’s mother remarried in Seaford on March 13, 1943, to Edward Bird Tull (1883–1951), himself a widower. One of Tull’s sons, Seaman 1st Class James Albert Tull (1910–1945), was killed in action when the U.S.S. Indianapolis (CA-35) was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine.

Ferrying Flights

The 819th Bomb Squadron ferried B-24s to the Central Pacific before the unit was committed to combat there. A squadron history indicated that in November 1943, Lieutenant Lurcott’s crew (probably including Johnson) flew from Hickam Field, Hawaii, to Nanumea, with intermediate stops at Canton and Funafuti. The history stated that Lurcott ferried another aircraft to the Central Pacific beginning December 2, 1943. Johnson must have flown with him, since he wrote to his mother on December 10, 1943: “I just got back this afternoon from a nine day trip. I got to see a lot of the Pacific Ocean and not much else except a few islands.”

38th or 819th Bomb Squadron?

Some sources list Lieutenant Johnson as a member of the 819th Bomb Squadron, while others list him as a member of the 38th Bomb Squadron. Contemporary documents were inconsistent in what his status was.

The 819th Bomb Squadron unit history stated that Johnson and his crew transferred out of the unit. Similarly, a squadron morning report stated that Johnson and the others were transferred to Section “Y,” 30th Bomb Group, effective January 13, 1944. On the other hand, the 38th Bomb Squadron history and morning reports stated that Johnson and his crew were attached to their squadron from the 819th.

Several documents in Lieutenant Johnson’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) list each squadron as his last unit. An additional 1945 document in his I.D.P.F. states that Johnson was on detached service to the 38th from the 819th at the time of his death. Other crews went on detached service from the 819th to the 38th and then returned to their original squadron. Lurcott and Johnson probably would have returned to the 819th as well if not for the crash.

Date of Death

Virtually all documents state that Lieutenant Johnson and his crew were killed on January 21, 1944. That date was provided to the families in 1944 and appeared more recently in Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency press releases.

Oddly enough, some documents suggest that the crash occurred on January 22, 1944. The Missing Air Crew Report (M.A.C.R.) stated that the aircraft crashed on January 21, 1944, at 1238 hours G.C.T. (Greenwich Civil Time, an outdated term for Greenwich Mean Time, also referred to as Zulu Time in military circles). The same date and time appeared in a report by the squadron intelligence officer about the casualties. It is also consistent with “Consolidated Mission Report, #63” dated January 22, 1944: “Two aircraft were destroyed on take-off; seven aircraft completed the mission. Take-off was started 211200Z [and] completed 211237Z.” That is, the B-24s began taking off at 1200 hours Zebra Time Zone (now Zulu Time) on January 21, 1944, with the last takeoff at 1237 hours.

That the crash occurred at 1238 hours could not have referred to local time, as multiple sources including the mission report describe the mission as beginning at night. For instance, an 819th Bomb Squadron history stated:

On the 23rd of the month [of January 1944], the 819th received the sad news of its second operational loss. 1st Lt. Howard L. Lurcott and his crew had crashed at Tarawa during a midnight takeoff on the 21st. It was to be their first combat mission. Details of the crash were missing, but “Lurks” plane and one other had crashed into the sea, in the stygian blackness at Tarawa, and their bombs had exploded.

Local time on Tarawa was—and still is—12 hours ahead of G.M.T. In other words, if those records are accurate, B-24J 42-72999’s crash occurred just after midnight on January 22, 1944, at 0038 hours local time. Indeed, the 38th Bomb Squadron’s January 1944 history stated that “on January 22nd two (2) squadron airplanes had crashed on take off at Tarawa. Lt Lurcott’s crew was lost, and only three men were saved from Lt Skaalen’s crew.” On the other hand, another document in the very same monthly squadron history report stated that the crash happened on January 21, 1944!

I believe it is possible that whoever filled out the casualty reports overlooked that the time of the crash was in G.C.T. It is also entirely possible that whoever filled out the M.A.C.R. made an error when recording the date and time. Frustrating as they are, it is not uncommon to find discrepancies in dates, times, and locations in M.A.C.R.s, histories, and other contemporary documents.

Johnson’s Wife

After Lieutenant Johnson shipped out for the Pacific, Lucille Butler Johnson returned to Baltimore, where she got a job as an inspector working the evening shift at the Bendix radio factory. She sometimes wrote to Alice Tull, who she referred to as “Mom.”

On August 20, 1945, 19 months after Lieutenant Johnson’s death, Lucille remarried in Milton, Delaware, to Ralph Willard Elliott (1919–1983). Corporal Elliott had been serving in the 1st Armored Division when he was captured during the Battle of Kasserine Pass in Tunisia on February 14, 1943. He spent over two years as a prisoner of war in Italy and Germany before he was freed close to the end of the war in Europe on May 2, 1945. Corporal Elliott was discharged from the U.S. Army on August 10, 1945.

In an emotional letter to Johnson’s mother dated August 26, 1945, Lucille explained that she had remarried to Elliott:

Maybe you expected it. I can’t say just why I went ahead and did it so soon, except that I got kinda disgusted with everything in general and just about to the point where I didn’t much care. Anyway that’s beside the point. It’s all over and done now.

But Mom, I want you to always be my Mom. That’s the way I’ll always think of you and Pop. And I hope that you will think of [Ralph] as one of yours too.

The Elliotts raised three children. After their deaths, Lucille and Ralph Elliott were buried at the Odd Fellows Cemetery in Seaford, where Lieutenant Johnson was eventually buried.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Lieutenant Johnson’s niece, Judi Thoroughgood, for providing photos and an excellent collection of Johnson’s letters, which proved invaluable in telling his story.

Bibliography

“213 Guardsmen to Get Medals.” Journal-Every Evening, February 25, 1937. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/83801691/private-johnson-bronze-bar/

“Army, Navy Report Four State Men Dead and Two Wounded.” Journal-Every Evening, February 23, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/83754655/george-m-johnson-killed/

“Awards Made to Guardsmen.” Journal-Every Evening, March 23, 1938. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/83801420/johnson-as-corporal/

“Bomber Pilot Killed in Action in Pacific.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 5, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/84283133/lurcott-killed/

Census Record for George Johnson. April 13, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00547-00353

Census Record for George M. Johnson. April 7, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531895_00217

Census Record for James E. Johnson. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. January 31, 1920 – February 5, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4295768-00980

Certificate of Birth for George E. Johnson. May 8, 1920. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6GVS-VVH

Certificate of Marriage for James Everett Johnson and Alice Wheatley. February 24, 1915. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1673/images/31297_212281-00272

Certificate of Marriage for Ralph W. Elliott and Lucille Johnson. August 20, 1945. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61368/images/TH-266-12356-31037-68

“Col. Whitson’s Records” (25th Antisubmarine Wing records). Reel B0934. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Dulin, Charles J. “Organizational History 819th Bombardment Squadron (H) 30th Bombardment Group (H) VII Comber Command Seventh Army Air Force.” April 6, 1944. Reel A0662. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Edward Bird Tull.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/122606226/edward-bird-tull

“Eight More State Soldiers Are Liberated in Europe.” Journal-Every Evening, May 26, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/85190764/ralph-elliott-free/

Gaines, William C. “Historical Sketches Coast Artillery Regiments 1917-1950.” http://cdsg.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/FORTS/CACunits/CAregNG.pdf

George M. Johnson Individual Deceased Personnel File. National Archives.

“Headquarters 604th Q.M. G.R. Co. Company Diary.” February 21, 1946 – June 10, 1946. WFI Research Group website. https://www.wfirg.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/604TH_QM_GR_CO_FEB-JUNE_46.32193551.pdf

Individual Deceased Personnel File for George M. Johnson. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Jack R. Busch. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Johnson, George M. Letters dated February 6, 1940 – January 19, 1944. Courtesy of Judi Thoroughgood.

Johnson, Lucille Butler. Individual Military Service Record for George McCullen Johnson. Undated, c. 1945. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/19390/rec/7

Johnson, Lucille Butler. Letters dated December 21, 1942 – August 26, 1945. Courtesy of Judi Thoroughgood.

Lamm, Louis J. Missing Air Crew Report No. 2629. February 18, 1944. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Mary Alice Tull.” The Morning News, July 24, 1984. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/85165396/mary-alice-tull-obituary/

Metheny, Hannah. “Historical Report: 2d Lt George M. JOHNSON.” November 19, 2019. Courtesy of Judi Thoroughgood.

“Monthly Flying Time 3rd Antisubmarine Squadron (H).” December 1942–August 1943. Reel A0522. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jan 31 1941 Btry A 261st Sep CA Bn.” January 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604_01.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jul 31 1941 Btry A 261st Sep Bn.” July 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604_01.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Mar 31 1942 Btry A 261st Sep Bn.” March 31, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604_01.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Nov 30 1941 Btry A 261st Sep Bn.” November 30, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604_01.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Oct 31 1941 Btry A 261st Sep Bn.” October 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0604_01.pdf

Morning Reports for 11th Antisubmarine Squadron. March 1943 – April 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0112/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0112-13.pdf

Morning Reports for 38th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy). January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0705/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0705-19.pdf

Morning Reports for 819th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy). January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0701/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0701-18.pdf

Morning Reports for Battery “A,” 261st Coast Artillery Battalion (Harbor Defense). February 1941 – March 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0923/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0923-01.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0923/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0923-02.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0923/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0923-03.pdf

“Narrative History 819th Bomb Sqdn (H) Nov 1940 – Feb 1944.” Reel A0662. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Organizational History, 38th Bombardment Squadron (H), 30th Bombardment Group (H), VII Bomber Command, Seventh Air Force. 1 January 1944 to 31 January 1944.” Reel A0550. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Pilot Accounted For From World War II (Johnson, G.).” March 18, 2020. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency website. https://www.dpaa.mil/News-Stories/News-Releases/PressReleaseArticleView/Article/2041019/pilot-accounted-for-from-world-war-ii-johnson-g/

“SSGT John Rowland ‘Jack’ Busch.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/92105284/john-rowland-busch

Stevens, Theodore S. “Consolidated Mission Report, #63.” January 22, 1944.

Thompson, Thomas E. Letter to Alice Tull dated April 26, 1944. Courtesy of Judi Thoroughgood.

Vogl, Joseph F. “Report of Official Travel.” May 18, 1950.

Vogl, Joseph F. “Van Fleet, George Jr., 0 917 892 (Discrepancy Case).” January 9, 1950.

“Weddings.” Wilmington Morning News, June 18, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/83754348/george-m-johnson-wedding/

Young American Patriots: The Youth of Maryland and Delaware in World War II. National Publishers, Inc., 1950. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8941/images/md_de1-0324

Last updated on October 30, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.

Pingback: #VeteranOfTheDay Army Veteran George Johnson » Disabled Veterans Alliance