| Home State | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware | Worker for Bond Bottling Corporation |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32485323 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “C,” 146th Engineer Combat Battalion |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Normandy |

Early Life & Family

Walter John Dobek was born at 401 Porter Street in Wilmington, Delaware, on the morning of September 28, 1922. His birth certificate recorded his name as Waslaw Dobek, but all other known records are under the name Walter. He was the ninth child of Peter Dobek (c. 1881–1944) and Mary Dobek (c. 1893–1926). Both parents were Polish, though Poland was not an independent country at the time they were born.

According to the 1920 census, Peter Dobek was born in Russia and immigrated to the United States in 1901, while Mary Dobek had been born in Galicia (then part of Austria-Hungary) and arrived in the U.S. in 1902. The couple had settled in Delaware by 1911, when their first child was born. By January 1920, the family was living at 745 Maryland Avenue in Wilmington, Delaware. Dobek’s father was working as a laborer in a shipyard, though he was described as a baker on Dobek’s 1922 birth certificate.

Dobek had four older sisters, while four other older siblings died before he was born. Another younger brother was born prematurely and died the same day, and his youngest sister was stillborn. He was only three years old when his mother died on May 6, 1926. The Dobek family was not recorded on any known census records from 1930 or 1940. According Journal-Every Evening, Dobek “attended St. Hedwig’s Parochial School” though his highest level of education is unknown.

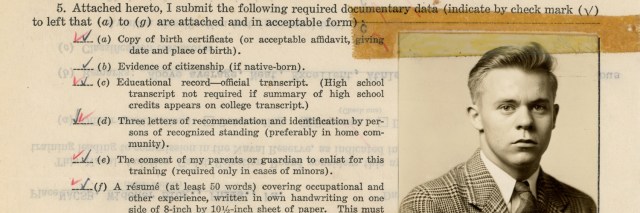

When he registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, Dobek was living with his sister, Ann Zoladkiewicz (1915–2000), at 700 Spruce Street in Wilmington and working for the Bond Bottling Corporation. He was described as standing five feet, 8½ inches tall and weighing 145 lbs., with brown hair and gray eyes. He was Catholic.

Military Training

After Dobek was drafted, he was inducted into the U.S. Army on December 21, 1942. He briefly transferred to inactive duty in the Enlisted Reserve Corps. According to the individual military service record filled out by his sister, Ann, Private Dobek went on active duty at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on December 29, 1942. She stated that he was stationed at Camp Carson, Colorado, from January 10, 1943, through May 30, 1943, and then moved to Shreveport, Louisiana, where he was stationed between June 1, 1943, and September 1, 1943. After that, he was stationed at Camp Swift, Texas, between September 2, 1943, and September 26, 1943.

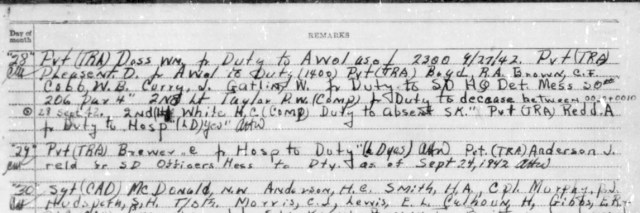

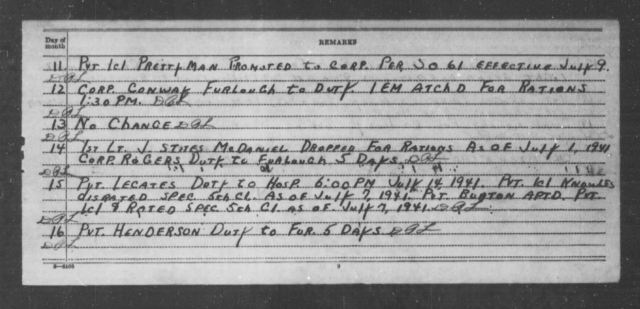

U.S. Army payroll records confirm that Private Dobek was recalled to active duty on December 29, 1942. He was assigned to the Corps of Engineers. Per Special Orders No. 357, Reception Center, 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey, dated December 31, 1942, he was among a group of men transferred to the 49th Engineer Combat Regiment. In January 1943, he joined that regiment’s Company “F” at Camp Carson.

Effective April 1, 1943, the 49th Engineer Combat Regiment was broken up, with its Company “F” becoming Company “C,” 237th Engineer Combat Battalion. Private Dobek was listed on the new unit’s initial roster with the duty of 521, basic. A set of orders dated August 8, 1943, transferred Private Dobek to the 49th Engineer Combat Battalion, which was temporarily stationed at the Louisiana Maneuver Area. The 49th Engineer Combat Battalion was previously 1st Battalion, 49th Engineer Combat Regiment prior to the breakup of the regiment. If he did join the 49th Engineer Combat Battalion, it was only briefly, since his name was not listed in August or September 1943 payroll records. Payroll records also indicate that he served briefly with the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion.

On May 1, 1944, in Braunton, England, about a month before he departed for Normandy, Private Dobek sat down to write a letter to his family to describe events since he joined his final unit the previous September. Soldiers’ overseas mail was heavily censored, usually preventing them from writing anything substantive about their experiences.

Dobek wrote: “Now this letter will sound sort of [mysterious] to you, but I’ve actually had such a life.” He added that he considered the nine-page letter “to be sort of a ‘Last Will and Testament.’” Dobek marked the letter as a private diary, accepting that it would be embargoed, perhaps for months or even years. He explained: “You won’t get this letter for some time. Until after all censorship has stopped, because there’s plenty of military information in this letter that we can’t let loose at the present moment.”

In his letter, Dobek recalled that he spent about six weeks stationed in Texas. However, he wrote, “When I learned that the 146th was mooving [sic] out for Overseas I asked for a transfer to it and got it on the day they were mooving out.”

Indeed, unit records confirm that on September 22, 1943, orders came down transferring Private Dobek from the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion to Company “C,” 146th Engineer Combat Battalion. Two days later, Private Dobek’s new unit began their move to Camp Myles Standish, Massachusetts, staging area for the Boston Port of Embarkation. The battalion arrived at Camp Myles Standish on September 28 or 29, 1943.

In his letter, Dobek recalled that “I really had myself a swell time” at Camp Myles Standish. He added:

We got two passes which we were [there] and I damn near spent a fortune in those two days. Maybe you would like to know how I got that fortune. Well pay day came while we were [there] and naturally a big crap[s] game brew up. Well I took the game broke and won $75000.

Indeed, $750 was a small fortune, worth about $13,500 in 2024 dollars! Nonetheless, Dobek claimed that “I spent all that in the two pass days we had on nothing but women and liqu[o]r, but I had a good time anyway.”

The following month, on October 8 or 9, 1943, the unit shipped out from the Boston Port of Embarkation aboard the R.M.S. Mauretania, arriving in the United Kingdom 10 days later. Private Dobek was just one among hundreds of thousands of soldiers arriving in England in preparation for the invasion of France the following year, Operation Overlord.

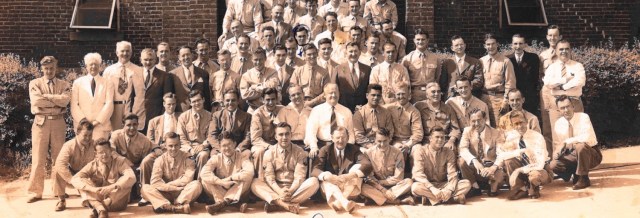

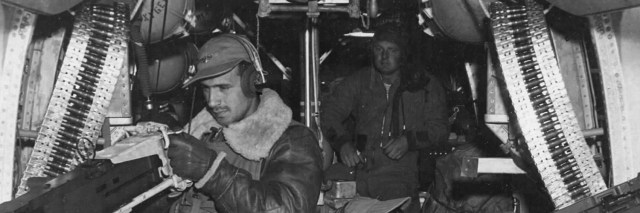

From late October 1943 through early April 1944, the battalion was stationed at the U.S. Assault Training Center in Devon, England. The unit built the simulated fortifications used to train the soldiers scheduled to land on the beaches of Normandy.

Dobek wrote:

We landed in Liverpool and shipped out the same day to a small town called Braunton. That’s where I am now. In this town or on the outskirts of it is a great training course where all combat troops come for training. We went through it and it’s a battle field in its self. They have artillery fire over it[,] machine gun fire[,] air plane str[a]ffing and bombings also beach head landings in navy boats. The ammunition used is real and I’ve seen plenty of boys get wounded or killed.

Wesley Reid Ross (1919–2017), then a 2nd lieutenant in the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion, later wrote in his memoir, Essayons: Journey with the Combat Engineers in WWII, that his unit was a relatively late addition to the list of units earmarked to land at Omaha Beach on D-Day in Normandy. Ross stated that Major General Leonard T. Gerow (1888–1972), commanding officer of V Corps

became concerned that 290 men in 21 Naval Combat Demolition Units (NCDUs)–who had been programmed for the beach obstacle demolition mission–were too few for the task. […] The revised plans called for demolitioneers from the 146th and 299th Engineer Combat Battalions to form twenty-four, 28-man Gap Assault Teams (sixteen Primary and eight Support GATs) to which the NCDUs would now be attached. This combined force was to blow sixteen fifty-yard-gaps through the wood and steel obstacles, located below the high tide line.

Soon after their departure from the Assault Training Center, the men of the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion found themselves back there, this time as trainees.

In a narrative dated June 1, 1944, Captain Stephen Pipka (1916–2009) wrote: “The Battalion’s regular organization was radically changed for the proposed operation. The three companies lost their platoon identity and the men were organized into boat teams.”

Ross later recalled that:

Our Primary GATs were to clear eight 50 yard paths through the obstacles for the Battalion Landing Teams of the 116th Infantry, 29th Infantry Division and our four support GATs were to be directed to their landing sites by the radio in Lt Colonel Isley’s command boat.

In his May 1, 1944, letter, Dobek wrote:

Now when I go into this Invasion I’ll be on the front lines. Our job is to blow up all the obstacles that are on the beach and in the water. We have to get the ones under water first so that the landing crafts can get into shore and drop off the Infantry to cover us with fire. I get sick in the [stomach] when I think how I’ll be bobbing around in the water with a 100 lbs of T.N.T. on my back and still having them shooting at me. If we get that done and if we’re still alive[, w]e have to go on and blow the obstacles on the beach so that the tanks and other heavy equipment can come through and make a little headway.

He added:

Look, I don’t want you to believe this, but I’ve got a hunch that I might not get out of this alive. So, in case I do get killed I want you all to d[i]vide what I have equally. That includes pop and you four sisters of mine. I have a $10,000 insurance policy which you will receive in partial payments and also a little money in the bank. So try and make the best of it as you can.

D-Day in Normandy

Dobek and the other engineers began landing on Omaha Beach within minutes of H-Hour. Many of them fell victim to the fusillade of German machine gun, rifle, and artillery fire that also devastated the first wave of infantry. Unlike other soldiers on the beach, the engineers’ mission meant they could not push forward to find cover. Complicating matters was the fact that other soldiers sought shelter behind the obstacles that the engineers were affixing explosives to.

In his book Omaha Beach: D-Day, June 6, 1944, Joseph Balkoski wrote:

The casualties among the demolition teams within the first thirty minutes of the invasion were so great that no historical account of their work can ever be complete. However, survivors’ narratives and unit reports agree that the combined army-navy teams managed to fulfill at least a small portion of their overall beach clearance mission. Of the sixteen fifty-yard breaches the mission called for, the demolitionists probably finished six and partially completed several more before the tide rose to a level at which work was impossible. […] Most of the gaps that were blown through the German obstacles on D-Day morning were on the eastern half of the beach, generally in the Easy Red sector between the St. Laurent and Colleville exits. Omaha’s western side, the 116th Infantry’s sector, probably had only two breaches, neither of which was anywhere near the western-most draw at Vierville—a failure that would later prevent landing craft from coming ashore in this sector.

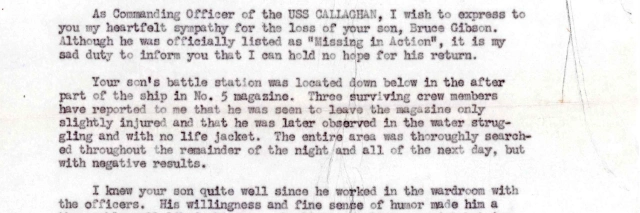

According to a report, “History of 146th Engineer Combat Battalion, 1 June 1944 to 30 June 1944,” the unit suffered D-Day casualties of 14 killed, 68 wounded, and 20 missing. According to the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion plaque at Colleville-sur-Mer, 35 men from the unit died on June 6, 1944. Private Dobek, one of missing, was subsequently identified among the dead. Personal effects found on his body were his wallet, his paybook, a pencil, and a pocketknife. Other personal effects that he left behind included a rosary, a rink, a checkerboard, a puzzle, two marksmanship badges, a pipe, a deck of cards, and a pair of dice.

A July 7, 1944, article in Journal-Every Evening stated:

A War Department telegram announcing that Private Walter J. Dobek, 21, has been missing in action in France since D-Day, was sent to his father, Peter Dobek. But it never reached that destination for the father had died on Tuesday.

The 146th Engineer Combat Battalion was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for the unit’s collective actions on June 6, 1944. Private Dobek was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

Private Dobek was initially buried on the afternoon of June 8, 1944, at a temporary American cemetery at Saint-Laurent. In 1948, Dobek’s oldest sister, Rose Wyszynski (1911–1994), requested that he be buried in a permanent cemetery overseas. Dobek was reburied in the permanent cemetery at Saint-Laurent, now known as the Normandy American Cemetery.

Notes

Parents’ Names

Peter Dobek was also known as Piotr Dobek.

There is considerable variation in how Mary Dobek’s maiden name is listed in various records including Maria Smosna, Marya Smosna, Mary Smozna, and Mary Bijos. Other records refer to her as Maryanna Dobek. Her death certificate listed her parents as John and Victoria Bigos. Indeed, the 1910 census lists John, Victoria, and Mary Bigos living in Wilmington.

Service in Italy?

Oddly enough, in his May 1944 letter, Private Dobek told his family:

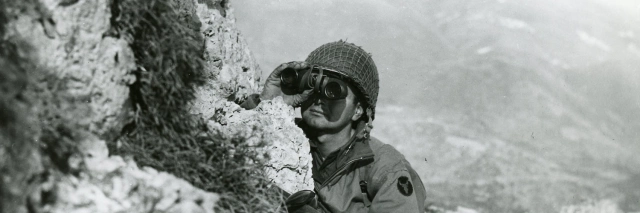

You remember when I got the new A.P.O. No. [Army Post Office number] that was right after New Year. We left England and went to Africa. From [there] we went to [S]icily and on up to the fighting front. I was scared to death on our first few battles. But the fright soon left me, and I was just like a mad man. I didn’t care if I died because I’ve already had my share in Germans. I don’t know the actuall [sic] amount I’ve killed but I won’t go any lower than a dozen which I am [sure] of.

He added:

Although I have already taken part in actual combat on the Adriatic front in Italy for a little over two months it wasn’t half so risk as the one I’m going into now. I was called and the whole battalion included, from Italy to report back to England for training which was to take part in the great invasion of Europe.

So far luck was with me and I got through the little fighting we did without a scratch. Although I’ve seen some of my closest friends fall and die at my side. But they were a bit careless and too enthusiastic. I’ve learned not to take any chances, but to wait for an op[p]ortunity, unless [there] was no other way out.

These passages are the most mysterious parts of the letter. 146th Engineer Combat Battalion histories do not mention the unit ever serving in the Mediterranean. Although it is theoretically possible that he could have been with a detachment that was sent to Italy but not mentioned in the unit history, in early 1944 most American troops were stationed on the west coast of Italy, with the British Eighth Army responsible for the Adriatic coast.

John D. Antkowiak, who has researched the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion for years, suggested that the passages about Dobek’s adventures in Massachusetts and Italy take on new meaning in the context of him writing what he expected might be the last letter his family would ever receive. Antkowiak posited:

If you think about it, what message does it convey to his dad and sisters if you take [Italy] out? “I’m scared to death.” I think that’s not the message he wanted to leave with them. […] I think it makes the most sense as a show of confidence and no-regrets in an attempt to mask actual fear and regret.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to John D. Antkowiak for supplying information about the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion, to Shelly DiPietrapaul for providing Private Dobek’s last letter, and to the Wyszynski family and Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photos.

Bibliography

Antkowiak, John D. Electronic correspondence, August 1, 2024.

Balkoski, Joseph. Omaha Beach: D-Day, June 6, 1944. Stackpole Books, 2004.

Census Record for Mary Bigos. May 4, 1910. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7884/images/31111_4327433-01374

Census Record for Peter Dobek. January 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4295770-00960

Certificate of Birth for Waslaw Dobek. Undated, c. September 28, 1922. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DYQ9-HYY

Certificate of Death for John Dobek. April 5, 1921. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1674/images/31297_212510-00670

Certificate of Death for Mary Dobek. May 7, 1926. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1674/images/31297_212519-00152

“D-Day Message Arrives Too Late.” Journal-Every Evening, July 7, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/70449528/walter-dobek-mia/

Dobek, Walter J. Letter to the Dobek family, May 1, 1944. Courtesy of Shelly DiPietrapaul.

Draft Registration Card for Walter J. Dobek. June 30, 1942. WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_09_00003-00802

Headstone Inscription and Interment Record for Walter J. Dobek. Headstone Inscription and Interment Records for U.S. Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942–1949. Record Group 117, Records of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1918–c. 1995. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9170/images/42861_1521003239_0888-01382

“History of 146th Engineer Combat Battalion, 1 June 1944 to 30 June 1944.” Originally posted on 146thecbwwii.org website in 2005 by Leonard Fox, copies provided courtesy of John D. Antkowiak.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Walter J. Dobek. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985.

“Initial Roster Company ‘C’, 237th Engr Combat Bn.” April 1, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/374228342?objectPage=758#object-thumb–758

“Narrative History 1 April 1943 to 1 June 1944.” Headquarters, 146th Engineer Combat Battalion. From the papers of Steven Pipka, courtesy of John D. Antkowiak.

“Narrative History 1 June 1944 to 30 June 1944.” Headquarters, 146th Engineer Combat Battalion. July 1, 1944. From the papers of Steven Pipka, courtesy of John D. Antkowiak.

“Pay Roll (For Enlisted Men) Company ‘C’ 146th Engr (C) Bn For month of September, 1943.” September 30, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0869/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0869_17.pdf

“Pay Roll of Company ‘C’ 237th Engineer Combat Battalion For month of August, 1943.” August 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/374228342?objectPage=851

“Pay Roll of Company ‘F’, 49th Engineer Combat Regiment For month of January, 1943.” January 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0725/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0725_04.pdf

Pipka, Stephen. “History 1 April 1943 to 1 June 1944.” Headquarters 146th Engineer Combat Battalion. Courtesy of John D. Antkowiak.

Pipka, Stephen. “Narrative History 1 April 1943 to 1 June 1944.” June 1, 1944. Headquarters 146th Engineer Combat Battalion. Courtesy of John D. Antkowiak.

“Pvt Walter John Dobek.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56643987/walter-john-dobek

Ross, Wesley R. Essayons: Journey with the Combat Engineers in WWII. http://www.6thcorpscombatengineers.com/docs/Engineers/Wes%20Ross%20-%20146th%20ECB.pdf

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

“Three from City War Casualties.” Wilmington Morning News, September 8, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/70446482/walter-dobek-kia/

Zoladkiewicz, Ann. Individual Military Service Record for Walter John Dobek. December 4, 1944. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18469

Last updated on September 2, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.