| Residences | Occupation |

| Delaware, Texas, Indiana | Career soldier |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | Enlisted 6219243 / Officer O-335798 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | 461st Amphibian Truck Company, 6th Engineer Special Brigade |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Normandy |

Early Life & Family

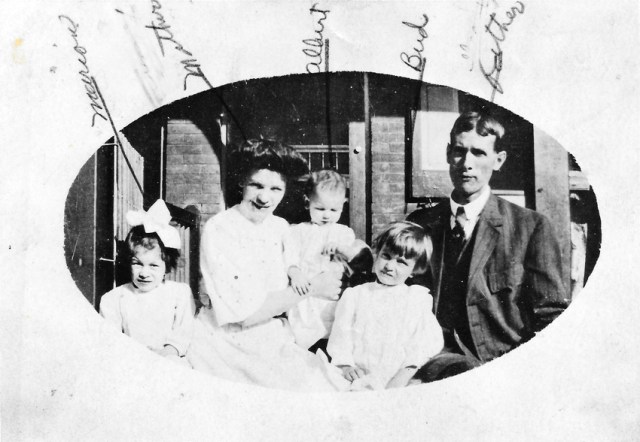

Charles Albert Wilson was born on July 23, 1908, at 2404 Lamotte Street in Wilmington, Delaware. A family photo suggests that he may have gone by his middle name. He was the son of Joseph Howell Wilson, Sr. (a Pennsylvania Railroad machinist, 1871–1925) and Mary Rebecca Wilson (Rebecca M. Wilson in some sources, 1881–1910). His mother had immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1896. Charles had an older sister, Marion Louise Wilson (later Ash, 1903–1979), and an older brother, Joseph Howell Wilson, Jr. (nicknamed Bud, 1905–1922).

The Wilson family was recorded on the census in April 1910 living at 1718 Lancaster Avenue in Wilmington. Later that year, on September 21, 1910, Charles’s mother died of tuberculosis. On March 21, 1912, Charles’s father remarried, to Annie E. Hickman (née Duffey, c. 1874–1940). By the time of the next census in January 1920, the family was living at 614 Concord Avenue in Wilmington.

The early 1920s were difficult for Charles. His brother, Joseph H. Wilson, Jr., died of peritonitis and appendicitis on February 24, 1922, aged 16. According to Charles’s son, he blamed his stepmother for not seeking medical treatment for Joseph quickly enough. The following year, his older sister married and moved out of the house. Charles’s father became ill in early 1924 and had to retire from the Pennsylvania Railroad. Later that year, in September 1924, he was hospitalized at the Delaware State Hospital in Farnhurst, leaving Charles living with his stepmother.

Charles ran away from home on May 20, 1925, aged 16. His family speculated that he had joined the circus. On May 26, 1925, his father died. The following day, an article in The Evening Journal reported:

The death of Joseph H. Wilson, aged 55 years, 614 Concord avenue, brought to light the fact that Charles A. Wilson, the 17-year-old [sic] son, has been missing from the home since last Wednesday when the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey circus played in Wilmington. News of Mr. Wilson’s death has been radiologued by the boy’s [stepmother] in the hope that the young man may be found before his father is buried.

Over 17 years later, a U.S. Army officer visited the Wilmington Morning News building, ostensibly looking for a lead on a friend he hadn’t seen for half his lifetime. On November 25, 1942, Wilhelmina Syfrit recounted the story he told in her column, “One to Another.” According to Syfrit, when Charles ran away:

He became from that moment the hero of one of the adventure books in which he had found refuge from a lonely youth.

He took the name of Stephen McGregor. He went to the West of which he had read. He worked days and nights and months as a migrate [sic] harvest worker. He went to foreign ports until the beckoning finger of adventure pointed to an Army recruiting post. It offered a chance for Stephen McGregor to make good. And Stephen McGregor did.

New Identity, Military Career, & Marriage

When he reinvented himself, McGregor added four years to his age, making his new date of birth July 23, 1904. That made him 21 as of the summer of 1925, which at the time was the youngest age a man could be and still enlist without parental consent. He claimed that he was born in El Paso, Texas, and that his father, Joseph McGregor, was also from Texas. Perhaps in a nod to his roots, McGregor stated that his mother was born in Delaware rather than Germany.

McGregor enlisted in the U.S. Army in Denver, Colorado, on August 11, 1925. A roster stated that Private McGregor joined Troop “B,” 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Bliss, Texas on August 30, 1925, about three months after he ran away. (In a quirk of fate, his son, Michael McGregor, also served in the 7th Cavalry during the Vietnam War.)

McGregor spent most of the next decade at Fort Bliss. He was briefly attached to Troop “E” on June 16, 1926, during a change of station to Crow Agency, Montana, but rejoined Troop “B” on July 1.

During the interwar era, soldiers often remained at the same grade for long periods of time and were often reduced back to private when transferring between units. McGregor was promoted to private 1st class in June 1927 but reduced back to private in September 1927, apparently after he was reported absent without leave (A.W.O.L.) on September 1. McGregor returned to military control 11 days later and was confined at the Presidio in San Francisco, California, from September 13, 1927, until November 27, 1927.

Private McGregor rejoined Troop “B” on December 16, 1927. Going A.W.O.L. could have serious repercussions on a soldier’s career. Remarkably, troop rosters document that the following year, in June 1928, McGregor was promoted two grades to corporal. Corporal McGregor was honorably discharged on October 30, 1928, after the expiration of his term of service. The following day, he reenlisted. In April 1929, his troop headed west on a series of moves: Hachita, New Mexico; Camp Harry J. Jones, Arizona; and Naco, Arizona. He returned to Fort Bliss in mid-May.

An April 1930 census record recorded Corporal McGregor at Fort Bliss. Later that year, he transferred to Troop “F,” 14th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, joining that unit as a private on July 31, 1930. He was promoted to private 1st class the following month and to corporal in October. He was transferred back to the 7th Cavalry on January 6, 1931, this time remaining as a corporal when he returned to Troop “B.”

Corporal McGregor reenlisted again on December 22, 1932. Soon after, on December 27, he left Fort Bliss on detached service for noncommissioned officer training at The Cavalry School, Fort Riley, Kansas. He arrived at Fort Riley on January 2, 1933. During mounted drill on the morning of April 29, 1933, a horse fell on McGregor, spraining his left ankle. He was treated at the Station Hospital, Fort Riley, Kansas, on May 1, 1933, and recuperated in quarters until May 5. It appears that he rejoined the 7th Cavalry later that month.

In the summer of 1934, McGregor was transferred to become an instructor at the Culver Military Academy in Indiana, an assignment that was under the organizational control of the V Corps Area Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (R.O.T.C), headquartered at Fort Hayes in Columbus, Ohio. McGregor arrived at Culver on August 3, 1934. As was customary in those days, the transfer came with a reduction to the private. Rosters indicate that he was briefly a field artillery instructor before switching to cavalry. He was promoted to sergeant on December 19, 1934.

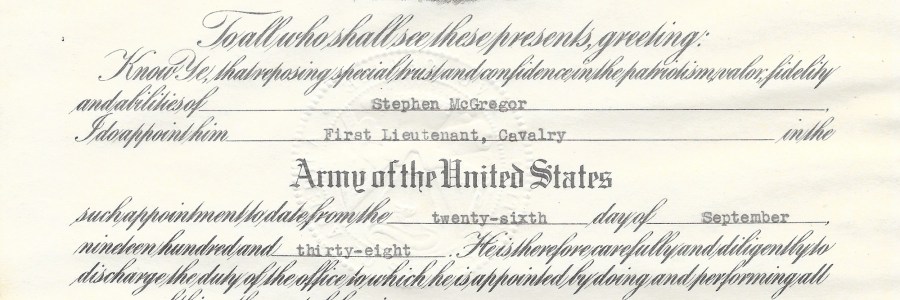

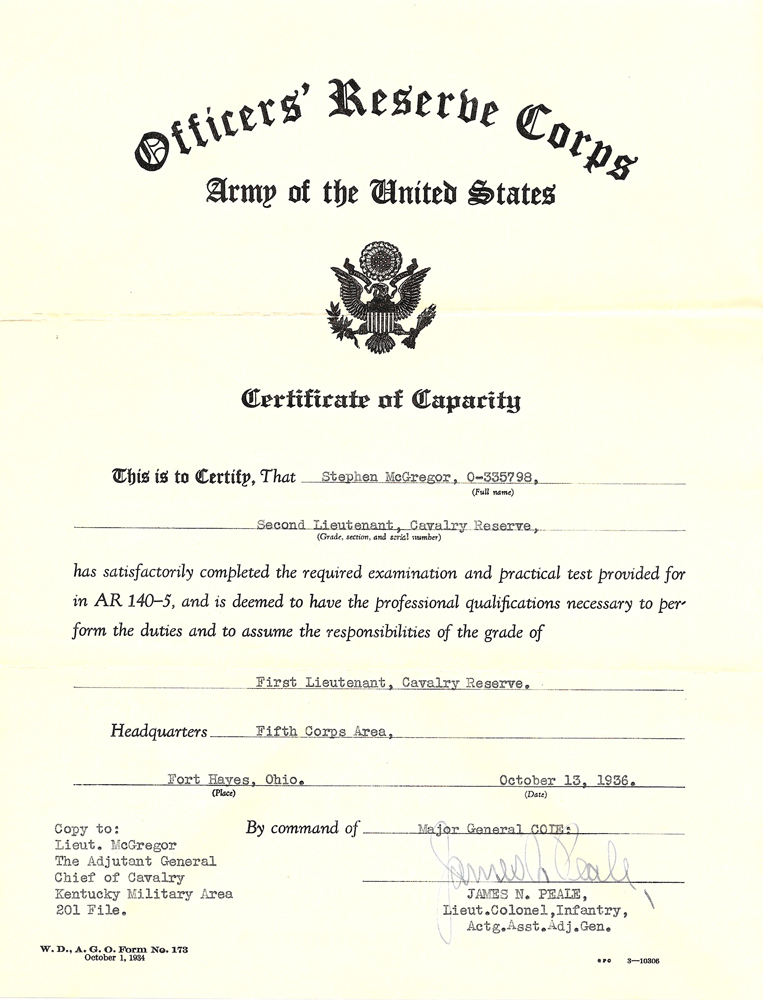

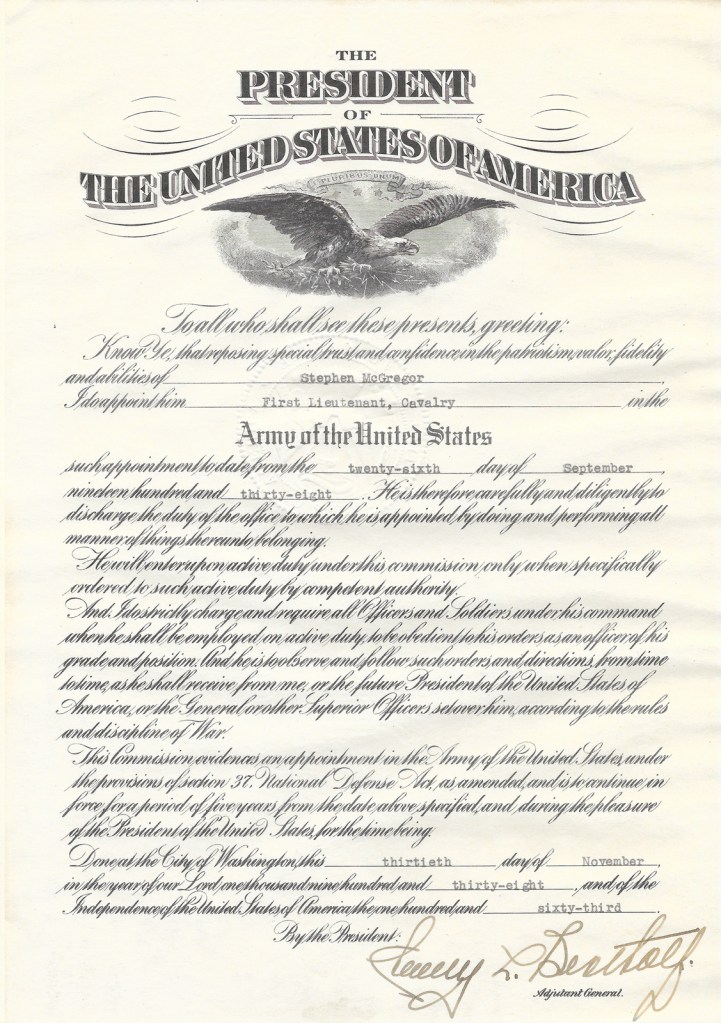

During the interwar period, it was difficult to become an officer. Very few were commissioned aside from those who graduated from West Point. Effective August 19, 1935, McGregor was appointed as 2nd lieutenant in the Cavalry Reserve. However, he did not immediately go on active duty as an officer, instead serving as a noncommissioned officer in the Regular Army for years afterward. The commissioning document stated: “He will enter upon active duty under this commission only when specifically ordered to such active duty by competent authority.”

Although still not called to active duty as an officer, on October 13, 1936, his superiors determined he was qualified for promotion to 1st lieutenant.

Wilhelmina Syfrit wrote in her column:

He became a crack polo player and rider. He was chosen as one of the cavalry instructors. There again was his opportunity. Nights and odd hours were devoted to acquiring the formal education.

A few miles from his post in the middle west he also found the modern version of the blonde sweetheart of Stephen McGregor, and legalized his chosen name, to give it to her.

McGregor married Alice A. Buczkowski (1910–1997) in South Bend, Indiana, on September 4, 1937. According to their son, his parents met at a Halloween party in South Bend. She complimented him on his costume and he explained that it was his uniform!

Although he still remained on inactive duty as an officer, McGregor was promoted to 1st lieutenant effective September 26, 1938.

The McGregors were recorded on the census in April 1940 living on College Avenue in Culver. McGregor was listed as having completed two years of college. McGregor was promoted to staff sergeant on October 10, 1940, and to technical sergeant on November 28, 1940. Two days later, Technical Sergeant McGregor was honorably discharged from the Regular Army as a formality. On December 1, 1940, over five years after he had first been awarded his commission, McGregor finally went on active duty as an officer.

According to an article in The South Bend Tribune, 1st Lieutenant McGregor was transferred to Fort Hayes in Columbus, Ohio. Indeed, on February 8, 1941, McGregor’s wife gave birth to the couple’s first child, Stephen (1941–2005), in Columbus. In 1943, the McGregors had a second son, Michael.

By June 1941, McGregor was the acting adjutant of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, 2nd Cavalry Division, at Fort Riley, Kansas. On August 21, 1941, McGregor and his comrades departed Fort Riley on a multistate journey by motor convoy: Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas. After maneuvers in Arkansas and Louisiana in late August and early September, the 3rd Cavalry Brigade returned to Fort Riley in early October 1941.

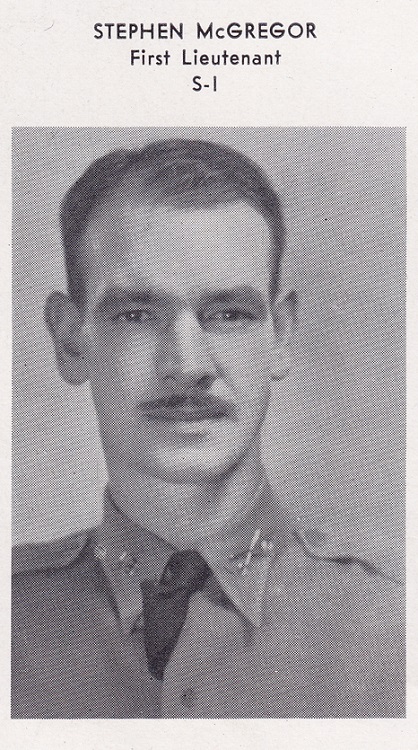

By the end of 1941, 1st Lieutenant McGregor was serving as S-1 (personnel officer) in the 3rd Cavalry Brigade. On December 12, 1941, days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the 3rd Cavalry Brigade headed south and west, moving through Texas and New Mexico before arriving at Camp Papago Park, Arizona, on December 17.

On or about February 28, 1942, Lieutenant McGregor transferred out of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade. He was attached unassigned to Station Complement Unit 1747, Fort Riley, Kansas, arriving on March 4, 1942. The following day, he was assigned to duty of assistant adjutant. On March 10, 1942, he departed Fort Riley to return to Culver Military Academy.

On March 12, 1942, 1st Lieutenant McGregor rejoined the Department of Military Science and Tactics at Culver Military Academy. As of June 29, 1942, McGregor was an assistant professor of military science & tactics, the commanding officer of the Detachment, 1508th Service Unit, and the unit adjutant. On that day he went on detached service to the Concordia School, Fort Wayne, Indiana, but returned to duty the following day. He went on detached service to Fort Hayes on July 26, 1942, returning to Culver on August 14.

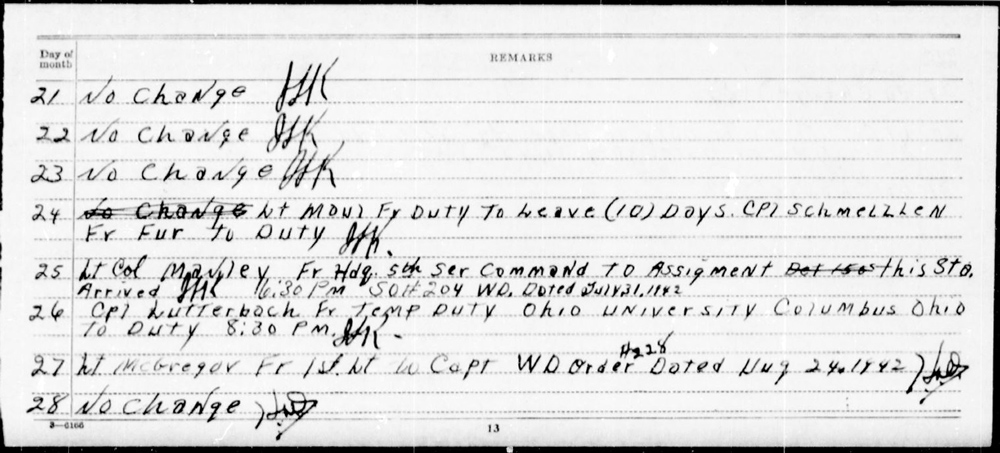

McGregor went on a temporary duty assignment at Toledo, Ohio, on August 19, 1942. He was promoted to captain effective August 24, 1942, and returned to Culver on September 4.

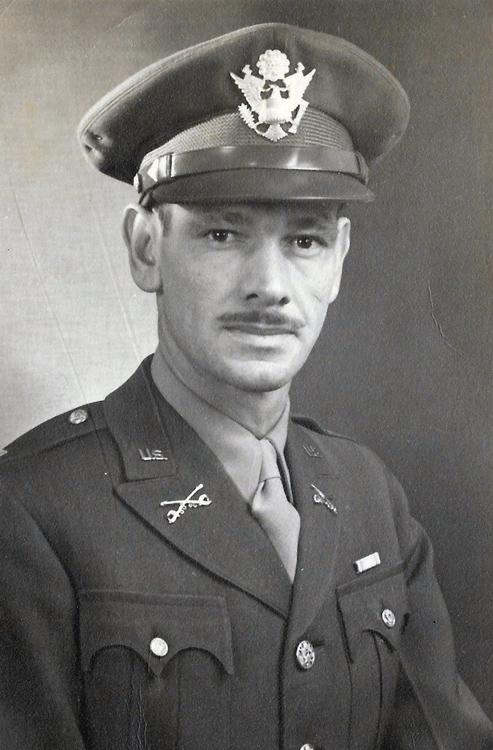

Captain McGregor began a 10-day leave on November 20, 1942, during which he visited Wilmington. At the time, Wilhelmina Syfrit described him this way: “The easy grace, the tanned skin of this six-foot three soldier spoke of years in open spaces. But more than that, there was the quiet assurance of a man who has learned to live within himself, and did so.”

Michael McGregor wrote: “My mother told me several times that McGregor turned down opportunities to stay stateside in training command because as a soldier he felt it was his responsibility to be in the action.”

A morning report indicated that Captain McGregor was transferred to Fort Riley, effective December 1, 1942. The South Bend Tribune stated that McGregor was stationed at the “to the cavalry replacement center at Fort Riley, Kan.,” though it is unclear if the article was referring to that transfer.

The early 1940s was a period of upheaval for the U.S. Army Cavalry branch. With the horse cavalry obsolete in modern warfare, some units were converted to other types, like infantry or armored units. Though mechanized cavalry squadrons and troops continued to perform the traditional roles of reconnaissance and screening, when Captain McGregor finally saw combat, it was with another branch entirely.

Company Commander & Overseas Service

Captain McGregor was the first commanding officer of the 461st Amphibian Truck Company, a Transportation Corps unit. He assumed command on July 6, 1943, the day after the company was activated at the Charleston Port of Embarkation, South Carolina. Equipped with the 2½-ton amphibious vehicle referred to as the D.U.K.W. or “Duck,” the company’s role was, per Table of Organization and Equipment No. 55-37: “To transfer cargo from shipside to shore dumps where pier facilities are not available.”

According to a contemporary company history, from July 5, 1943, through December 5, 1943, the 461st was “attached to the Amphibious Vehicle Training School, Charleston Port of Embarkation, Charleston, S. C.” On December 5, 1943, the unit boarded a northbound train, arriving the following day at Camp Shanks, New York, to stage before shipping out for Europe.

On December 22, 1943, at the New York Port of Embarkation, the 461st Amphibian Truck Company boarded the Île de France, a French ocean liner requisitioned by the British as a troopship. For unknown reasons, they disembarked on Christmas Eve 1943 and moved to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, another staging base for the New York Port of Embarkation. On January 1, 1944, they boarded another ocean liner turned British troopship, Queen Elizabeth.

The unit disembarked at Greenock, Scotland, on January 9, 1944, and arrived the following day at Exeter, Devon, England. On January 25, 1944, the company moved to Paignton, also in Devon. That same day, the company was attached to the 6th Engineer Special Brigade. On March 21, 1944, it was “Assigned to the 280th Quartermaster Battalion for administration.” The company moved to Torquay, Devon, on April 29, 1944. Later, on May 13, 1944, it was “Attached to the 149th Engineer C[ombat] Bn. for operations only.”

While stationed in Devon, Captain McGregor befriended Captain E.C. Hopkinson, a British soldier who had been decorated with the Military Cross while serving in 1st Battalion of the East Lancashire Regiment during World War I. Prior to D-Day, Captain Hopkinson presented Captain McGregor with three gifts. One was a cigarette case engraved with a poem:

Capt. S. McGregor / Thus will I remember / The place where fate threw me, / The little English home / Which looked out on the sea, / The brightly colored garden, / The cup of mellowed wine, / And the Brother Soldier / Who became a friend of mine.

Capt. E.C. Hopkinson, M.C.

Hopkinson also gave McGregor two books: Spectamur Agendo, which Hopkinson had written about his World War I unit, and another that he had cowritten, Sword, Lance and Bayonet. In the latter, Hopkinson enclosed a note:

To you, who, as we did in our youth, are to go across the water into battle may this bring all good fortune. On that day we, the older generation, hand over to you to finish off what is beyond us.

In our youth in battle we gave all we had to give. Then war-won we made mistakes. But credit us that in age we once again held fast [illegible] darkest adversity. […]

I only wish I could see you go, as recorded in this book; sabres flashing in the sun, [pennants] fluttering in the breeze.

Between March and May 1944, the 461st went on maneuvers three times to practice their role in the upcoming invasion. A 461st Amphibian Truck Company morning report stated that the unit “Debarked 1900, 4 May 44, Slapton Sands, Maneuver Area to perform a problem.” Presumably, that was Exercise Fabius I, a rehearsal for the Omaha Beach landing.

A diagram of planned units for Omaha Beach showed elements of the 461st scheduled to land at two sectors: Dog Red beginning around three hours into the invasion and Easy Green about four hours into the invasion.

An August 8, 1944, letter by Captain Hopkinson to Alice McGregor suggested that Captain McGregor welcomed his unit’s role in the invasion: “He had for some time back been fretting that he had only command of a ‘duck’ company as a regular officer but that had all changed when his company was ordered to lead his American army ashore.”

The 461st moved to Camp “D” in Dorchester, England, on May 15, 1944, to stage before boarding the invasion fleet. They boarded L.S.T.s (Landing Ship, Tank) at Portland Harbour, England, on June 1, 1944. All five company officers and 153 enlisted men shipped out from Portland at 1500 hours on June 5, 1944.

Captain Hopkinson wrote Alice McGregor a letter the following day:

As I lay awake this morning listening to the bombardment for, [illegible] the battle is about 90 miles from here, my doors & windows shook all night long, I remembered your husband said he would be grateful if I sent you a letter. I thought of him and his men for I imagine they were in the early waves of the landing.

I have not seen him for some little time but one thing I shall always remember; when he was leaving here he at the last moment found time to come and say good bye to me. I knew how busy he was & it was such a nice thing of him to do. I can only tell you he was fit and well and looked a splendid soldier, going off as he should, “grim and gay”, for he knew what he had to face. […] I had seen a lot of him as he had often invited me up to his Mess and been to my home many an evening and I think I had made for him and [McGregor’s executive officer, 1st Lieutenant N.R.] Watkin a home from home.

D-Day in Normandy

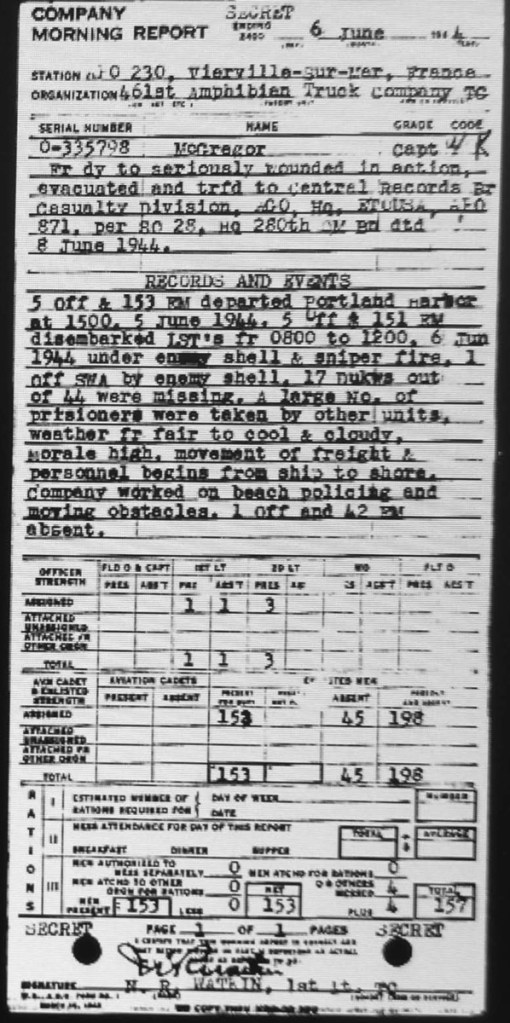

The 461st Amphibian Truck Company first went into action on D-Day in Normandy, June 6, 1944. The company morning report for that day stated:

5 Off[icers] & 151 EM [Enlisted Men] disembarked LST’s fr 0800 to 1200, 6 Jun 1944 under enemy shell & sniper fire. 1 off SWA [seriously wounded in action] by enemy shell. 17 Dukws out of 44 were missing. A large No. of prisoners were taken by other units, weather fr fair to cool & cloudy, morale high, movement of freight & personnel begins from ship to shore. Company worked on beach policing [cleanup] and moving obstacles.

Around 1000 hours on D-Day, Captain McGregor was killed or mortally wounded by enemy artillery. Various accounts have him being hit either on the beach or just offshore. It is also unclear how long he survived after being hit. The morning report stated that Captain McGregor was “seriously wounded in action, evacuated and trfd [transferred]” to England.

Captain McGregor’s executive officer, 1st Lieutenant (later Captain) Nathaniel Ring Watkin, Jr. (1913–1974) told his son years later that he and McGregor were swimming offshore from the beach when McGregor was hit by artillery and killed instantly.

It is unclear why they would have exited their D.U.K.W.s. One possibility is that they were blocked by beach obstacles. After he was told of Watkin’s account, Captain McGregor’s son also pointed out that “swimming” may have referred to the D.U.K.W.s operating in the water, rather than McGregor and Watkin themselves. Watkin assumed command of the company after McGregor was hit.

The 461st Amphibian Truck Company’s casualties were relatively light considering the carnage on Omaha Beach that day: two killed, including Captain McGregor, and one man wounded. Another man was killed the following day. Nine men were reported missing in action, all of whom were subsequently found alive, although at least one had been wounded.

The August 8, 1944, letter by Captain Hopkinson to Captain McGregor’s widow stated:

I am indeed sorry to hear your husband was killed in the Landing. I had heard from Watkin [that] he had been hit but none of them knew if he had been badly wounded or killed. I am afraid I can give you little news. It is poor consolation I well know to you but he died as he would have wished at the head of his men and not out of sheer bravado but because he considered it the best place to ensure success for his company. His company I have heard did very well & it was he who made his company by his example and previous training; he was respected by them all.

In the late 1990s, Michael McGregor contacted two enlisted men from his father’s unit. In a November 14, 1998, letter, one man, Dale Shultz, wrote to Michael sentiments that echoed what Captain Hopkinson had recorded over half a century earlier:

Your dad was a brave man. I admired him very much. He taught some of us how to stay alive way before D Day. Thru his training he was tough and that brought some of us out of WWII. I was fairly close to him when they were shelling us plus small arms fire.

The other, Paul Zeigler, told him in a phone conversation (paraphrased from Michael McGregor’s notes): “On the beach he was standing, directing troops to get up—as everyone was on their bellies—and move forward. I moved and then looked back and saw a shell hit and killed him instantly.”

It remains unclear if Captain McGregor died just offshore, on the beach, while being transferred back to the fleet offshore, or at a medical treatment facility (hospital ship or hospital back in England). Alice McGregor received one notification that her husband was wounded, followed by another that he had been killed. His status was recorded on the official 1946 casualty list as killed in action rather than died of wounds. If accurate, that meant he died soon after he was hit (as two eyewitnesses attested) and before reaching medical care. On the other hand, if he was killed instantly on the beach, his body would most likely have been buried in France rather than transported back to England. McGregor’s burial report stated that his place of death was unknown, while the Adjutant General’s Office report of death stated he was killed in France.

Captain McGregor was buried at the U.S. Military Cemetery, Brookwood, England. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. After the war, Captain McGregor’s wife requested that his body remain overseas. He was reinterred at what is now referred to at the Cambridge American Cemetery (Plot C, Row 4, Grave 63).

Postscript: A D-Day Artifact

During my research for this article in 2021, I located descendants of both Captain McGregor and his executive officer, Nathaniel Ring Watkin, Jr. On September 11, 2024, Watkin’s grandson, Nathaniel Ring Watkin, IV, reached out to ask for my assistance in returning a souvenir he found in Captain Watkin’s footlocker: a set of pistol grips for a Colt M1911 labeled with a tag identifying them as “Capt. Steven [sic] McGregor’s 45 Pistol handles at time of his death 6/6/44.”

I put Watkin’s grandson in touch with Captain McGregor’s son, Michael, who mentioned that his own son owned an M1911 and would see if they fit. On October 2, 2024, Michael McGregor, Jr. sent me a couple of photos of his grandfather’s pistol grips installed on his own pistol. Captain McGregor’s story remains one of the most fascinating ones I’ve researched to date, and to be an intermediary in the return of this family artifact is one of the most satisfying moments of this project yet.

Documents

Click below to view any document.

Notes

Mother’s Maiden Name

Mary R. Wilson’s maiden name is recorded as Johanns, Johuson, and Johannes in various sources.

2nd Cavalry Division

The American armed forces were segregated during World War II. Though it only existed briefly, the 2nd Cavalry Division was a rare example of a unit that was integrated at the brigade level. McGregor was an officer in the white 3rd Cavalry Brigade, while the 4th Cavalry Brigade was composed of black troops. However, only white soldiers were incorporated into the new 9th Armored Division in the summer of 1942. The following year, the 4th Cavalry Brigade was incorporated into a new 2nd Cavalry Division which was inactivated in North Africa in 1944 without seeing combat.

Spelling of Last Name

1944 articles in the Wilmington newspapers and his sister Marion L. Ash’s statement erroneously spelled Captain McGregor’s last name as MacGregor. As a result, subsequent newspaper articles, the Delaware memorial volume, and the list of names in Veteran’s Memorial Park in New Castle all use that spelling.

Vehicles

An August 10, 1944, Journal-Every Evening article stated that “His last letter to Mrs. Ash, in March, mentioned that he was in charge of 30 tanks to be used in the invasion.” Most likely this error was due to confusion over the fact that Captain McGregor’s unit was equipped with amphibious trucks, but not tanks. The error was repeated in a story on Delaware’s D-Day fallen published for the 50th anniversary of the invasion. The July 11, 1944, article in The South Bend Tribune also described his unit erroneously, albeit as “an amphibious tractor company.”

Enlisted Men Participating in D-Day

According to company morning reports, 153 enlisted men from the 461st Amphibian Truck Company participated in the D-Day invasion. For reasons that are unclear, about ¼ of the company (45 of 198 enlisted men) remained behind in England, with most of them rejoining the unit on June 13, 1944.

Captain Hopkinson’s Letter

The phrase “grim and gay” apparently referred to a quote from Winston Churchill describing the mentality of the ideal soldier. “Home from home” means “home away from home” in American English.

Morning Report Details of Transfer on June 6, 1944

The morning report stated that Captain McGregor was “seriously wounded in action, evacuated and trfd [transferred] to Central Records Br[anch] Casualty Division, AGO [Adjutant General’s Office], Hq, ETOUSA [European Theater of Operations, United States Army], APO 871.”

In most cases, morning reports listed the hospitals that wounded personnel were transferred to. Although Headquarters E.T.O.U.S.A. (and Army Post Office 871) were located in Cheltenham, England, it seems unlikely that a seriously wounded soldier would have been transported there rather than to a closer hospital at a port along the southern coast of England. Indeed, it seems most likely that this entry was for administrative reasons since the company clerk would likely have no way of knowing which hospital he ended up at.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Michael McGregor, Michael McGregor, Jr., Nathaniel R. Watkin, III, for supplying valuable information, documents and photos, and to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for obtaining prewar payroll and hospital records.

Bibliography

“Army Captain Killed D-Day; Three Hurt.” The South Bend Tribune, July 11, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/76302470/stephen-mcgregor-kia-indiana/

Ash, Marion L. Individual Military Service Record for Stephen MacGregor. Undated, c. 1947. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/19744

Census Record for Charles A. Wilson. April 27, 1910. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7884/images/31111_4327433-01459

Census Record for Charles A. Wilson. January 8, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4295770-00382

Census Record for Joseph H. Wilson. April 27, 1910. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7884/images/31111_4327433-01458

Census Record for Stephen McGregor. April 23, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4547952_00655

Census Record for Stephen McGregor. April 26, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/M-T0627-01077-00577

Certificate of Death for Joseph H. Wilson. 1925. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1674/images/31297_212517-00283

Certificate of Death for Joseph H. Wilson, Jr. 1922. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1674/images/31297_212511-01374

Certificate of Marriage for Andrew Hickman and Annie Duffy. November 10, 1897. Delaware Marriage Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1508/images/31091_177994-00235

Certificate of Marriage for Charles Wilmer Ash and Marion Louise Wilson. June 6, 1923. Delaware Marriage Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1673/images/31297_212300-00509

“Death Notices.” Journal-Every Evening, April 17, 1940. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/76449358/annie-e-wilson-death-notice/

“Final Statement of Stephen Mc Gregor, 6219243, Corp. Troop B 7th Cav.” October 30, 1928. Individual Pay Vouchers, c. 1926–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

Headstone Inscription and Interment Record for Stephen McGregor. Headstone Inscription and Interment Records for U.S. Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942–1949. Record Group 117, Records of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1918–c. 1995. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/168975854?objectPage=1033

Historical and Pictorial Review, 2nd Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Cavalry Division of the United States Army. The Army and Navy Publishing Company, 1941. Courtesy of Michael McGregor. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/1941-2ndcavalry-book-complete.pdf

Historical Record of the 461st Amphibian Truck Company. Undated, c. December 10, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

McGregor, Michael Jr. Phone interview on April 30, 2021, and email correspondence during May 1–23, 2021, and October 2, 2024.

Milford, Phil. “12 from Delaware lost their lives in invasion.” The News Journal, June 5, 1994. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/69101534/delaware-d-day/

Morning Reports for 461st Amphibian Truck Company. July 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2715/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2715-12.pdf

Morning Reports for 461st Amphibian Truck Company. May 1944 – June 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Michael McGregor, Jr.

Morning Reports for Detached Enlisted Men’s List, Culver Military Academy. October 1940 – November 1940. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824-12.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824-13.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment, 1508th Service Unit, Culver Military Academy. March 1942 – December 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824-14.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2824-15.pdf

Morning Reports for Headquarters Station Complement Unit 1747. March 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-3021/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-3021-23.pdf

Morning Reports for Weapons Troop, 3rd Cavalry Brigade. May 1941 – March 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0627/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0627-04.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0627/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0627-05.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0627/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0627-06.pdf

“Radio Calls Youth Home, Father Dead.” The Evening Journal, May 27, 1925. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/76388334/joseph-h-wilson-obituary/

Return of a Birth for Charles Albert Wilson. July 23, 1908. Delaware Birth Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1672/images/31297_212251-00817

Standard Death Certificate for Mary R. Wilson. 1910. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1674/images/31297_212490-00684

“State Casualty List Includes Three Killed.” Journal-Every Evening, August 10, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/76222590/captain-mcgregor-kia-delaware/

Syfrit, Wilhelmina. “One to Another.” Wilmington Morning News, November 25, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/76222464/stephen-mcgregor-of-wilmington/

“Table of Organization and Equipment No. 55-37: Transportation Corps Amphibian Truck Company.” May 22, 1944. Military Research Service website. http://www.militaryresearch.org/55-37%2022May44.pdf

U.S. Army Enlisted and Officer Rosters, July 1, 1918 – December 31, 1939. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/search/record/results?q.givenName=Stephen&q.surname=McGregor&f.collectionId=3346936

Watkin, Nathaniel R. III. Phone interview on May 23, 2021.

Watkin, Nathaniel R. IV. Email correspondence on September 11, 2024, and December 11, 2024.

Last updated on November 5, 2025

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.