| Residences | Occupations |

| New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware | Worker for General Chemical, later career soldier |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 12012293 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “K,” 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge (presumed) | Operation Torch, Tunisia, Sicily, Normandy |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Entered the Service From |

| 745 (rifleman) | Wilmington, Delaware |

Early Life & Family

Lauritz J. Andersen was born in Camden, New Jersey, on June 27, 1919, the son of Lauritz Johan Andersen (1892–1966?) and Julia Andersen (1892–1945). His father, a rigger, had immigrated from Norway and his mother from Austria-Hungary. Census records suggest that both father and son changed their names to Lawrence John Anderson by 1930. Anderson was nicknamed Larry. According to one of his service documents, he was Protestant.

Anderson had an older brother and two younger sisters. The Andersons were recorded living at 815 Morgan Street in Camden on the 1920 census. They were residing at the same address on October 5, 1920, when tragedy struck the family. Anderson’s older brother or half-brother, Edward Charles Anderson (c. 1915–1920), died of tetanus.

The census taken in April 1930 recorded the Anderson family living at 1134 Keystone Road in Chester, Pennsylvania. His father was working as an automobile rigger and his mother as a laundress. A newspaper clipping in Anderson’s wife’s collection from an unknown paper stated that the family moved to Chester when he was three.

The newspaper clipping stated:

He lived for 15 years in Buckman Village before moving to [316 Clayton Street]. He was a member of the Resurrection Church and attend[ed] Resurrection School. He worked for a time at General Chemical Company before enlisting in the Army 1940, when he was 21.

Anderson had moved to 404 West Seventh Street in Wilmington, Delaware by October 16, 1940, when he registered for the draft. At the time, he was unemployed. He was described as standing six feet tall and weighing 170 lbs., with brown hair and eyes.

Stateside Service & Mediterranean Theater

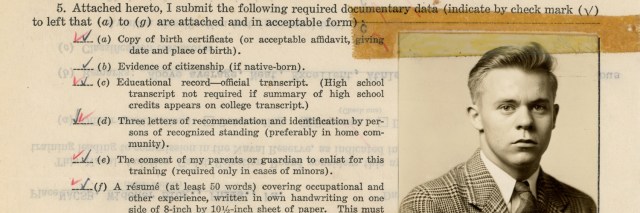

Not long after, Anderson volunteered for the U.S. Army, enlisting on November 7, 1940. A Journal-Every Evening article stated that he “enlisted for service in the army at the Delaware recruiting district, postoffice [sic] building” and would initially be assigned to the Medical Department at Fort DuPont, Delaware.

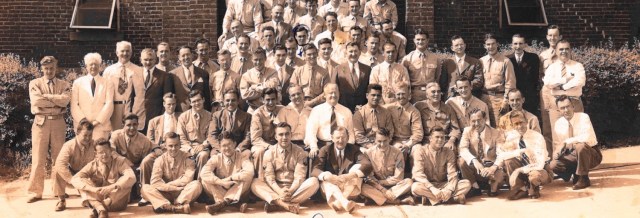

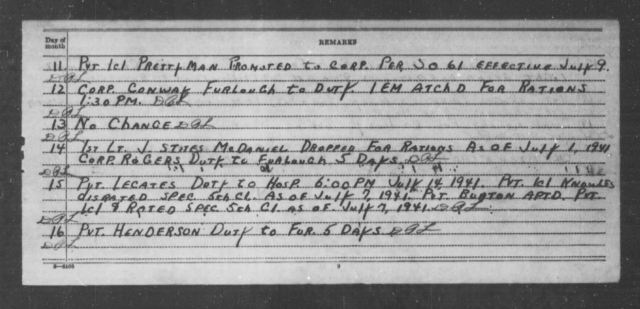

In July 1941, Private Anderson joined the Medical Detachment, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. A roster listed his duty as 060, cook. Unfortunately, the detachment’s morning reports from the period went missing before they could be microfilmed in 1950, so it is unclear if he joined the unit early in the month at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, or whether he joined in the second half of the month while the 16th Infantry was on maneuvers near New River, North Carolina. The 16th Infantry returned to Fort Devens in mid-August 1941. That month’s roster listed his duty as 521, basic. The regiment returned to North Carolina by road for maneuvers in mid-October 1941. The 16th Infantry arrived back at Fort Devens on December 6, 1941, the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

On February 20, 1942, Anderson and most of his comrades began a journey south by train, arriving two days later at Camp Blanding, Florida. On March 13, 1942, Anderson transferred to Service Company, 16th Infantry Regiment. That month’s roster listed his military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) as 521 (basic) but his duty as 060 (cook). On April 4, 1942, he was rated as a specialist 4th class and promoted to private 1st class the same day.

On April 27, 1942, Private 1st Class Anderson went on furlough for a visit home. While there, Anderson married Charlotte Elizabeth Stegnerski (1918–2000) in Brandywine Hundred, near Wilmington, Delaware, on May 3, 1942. Their marriage certificate suggests that she was working as both a hairdresser and operator at the time. The length of Anderson’s furlough seems to have precluded a honeymoon, since Anderson reported for duty back at Camp Blanding on May 7, 1942. Anderson and his unit left Camp Blanding by road on May 21, 1942, arriving the following day at Fort Benning, Georgia, where the 1st Infantry Division performed did a series of field exercises.

Anderson was reduced back to private on May 25, 1942. The following month, the 1st Infantry Division moved north to Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Pennsylvania. On July 7, 1942, Private Anderson transferred to his final unit: Company “K,” 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. On August 1, 1942, Anderson and his comrades departed Indiantown Gap by road, transferred to a ferry at Jersey City, New Jersey, and boarded the R.M.S. Queen Mary at the New York Port of Embarkation. They shipped out the following day, arriving in port in the United Kingdom on August 7.

In mid-October 1942, the 16th Infantry Regiment shipped out for the Mediterranean Theater, with 3rd Battalion (including Company “K”) aboard the British transport Duchess of Bedford.

On November 8, 1942, during Operation Torch, the 16th Infantry Regiment landed in Oran, Algeria, brushing aside resistance from the Axis-aligned Vichy French forces there. General Orders No. 35, Headquarters 1st Infantry Division (dated December 26, 1942) stated that Company “K” was “cited for outstanding performance of duty in action” for a November 9, 1942, action at Saint Cloud, Algeria “against a superior enemy force[.]”

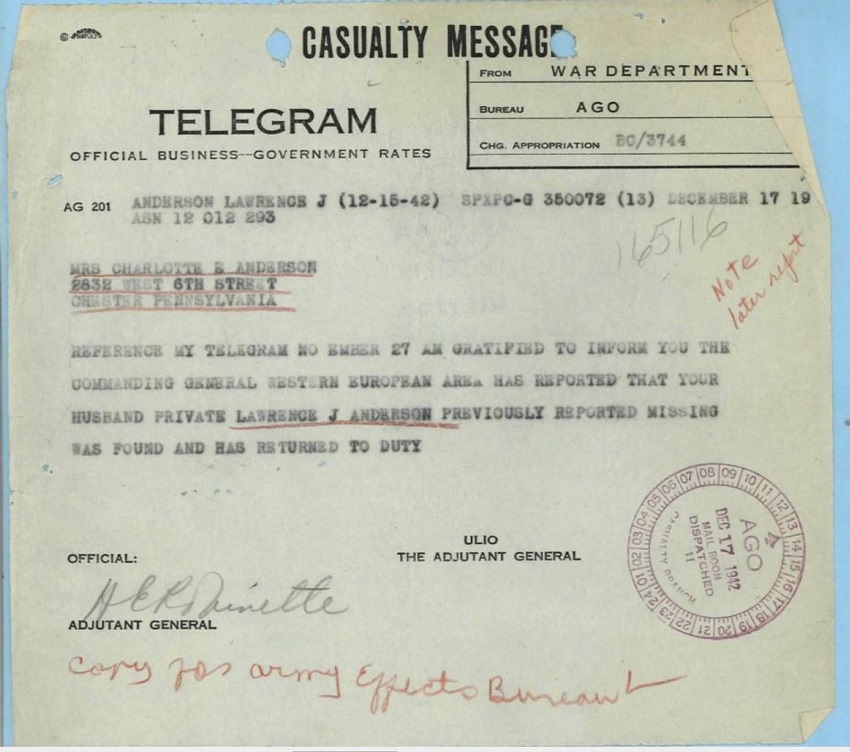

Anderson’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) includes a copy of a telegram from the Adjutant General to Anderson’s wife dated December 15, 1942, stating: “REFERENCE MY TELEGRAM NO[V]EMBER 27 AM GRATIFIED TO INFORM YOU THE COMMANDING GENERAL WESTERN EUROPEAN AREA HAS REPORTED THAT YOUR HUSBAND PRIVATE LAWRENCE J ANDERSON PREVIOUSLY REPORTED MISSING WAS FOUND AND HAS RETURNED TO DUTY[.]”

The telegram would seem to imply that Private Anderson had briefly been reported missing during Operation Torch, either due to the chaos surrounding the fighting or because he briefly was captured by the Vichy French. Curiously, neither the Company “K” morning reports nor rosters list Anderson as missing or captured.

Anderson was promoted to private 1st class effective November 23, 1942. Early the following year, he participated in the Tunisian campaign. On June 7, 1943, Anderson’s military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) changed from 745 (rifleman) to 060 (cook). Around that same time, he was promoted to technician 5th grade.

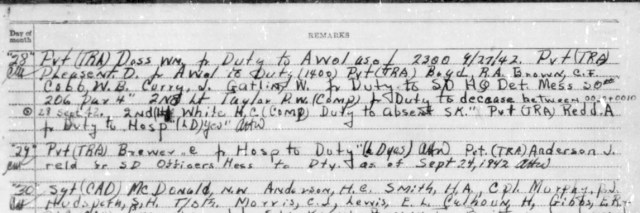

The 16th Infantry Regiment participated in the amphibious assault at Gela, Sicily, beginning early on July 10, 1943. Anderson was promoted to technician 4th grade on August 12, 1943. He was reduced to the grade of private effective October 15, 1943, and his duty changed to rifleman. It is unclear if his demotion was due to a minor disciplinary infraction or whether he requested the change in duty, surrendering his rank in the process. (His M.O.S. was also officially changed from cook to rifleman, but not until February 22, 1944.)

D-Day in Normandy

After the Sicily campaign, the 16th Infantry Regiment shipped out from Augusta, Sicily, on October 23, 1943, aboard the British transport Maloja. The regiment arrived back in the United Kingdom on November 5, 1943. Company “K” disembarked early the following morning and traveled to Abbotsbury, Dorset, England, by train and truck.

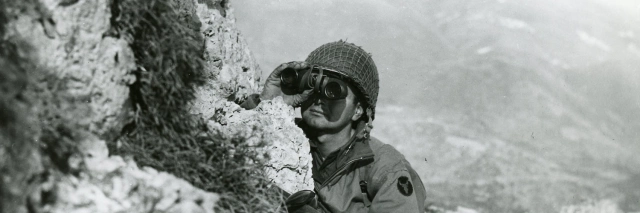

Soon after, the men began to train for the invasion of France, scheduled for the following spring. Unlike other American infantry divisions scheduled to land on D-Day, the Big Red One had both combat and amphibious experience.

On March 8, 1944, Company “K” moved to Weymouth, Dorset, England, for amphibious exercises before returning to Abbotsbury on March 13, where the company continued practice assaults and other training. Anderson was promoted back to private 1st class on April 1, 1944. Company “K” moved to Martinstown, Dorset, England, on April 25, 1944. On May 1, 1944, Private 1st Class Anderson and his comrades moved to Weymouth and boarded the British transport Empire Anvil for more amphibious exercises, before returning to Abbotsbury on May 7. The company left Abbotsbury for the last time 10 days later, returning to Martinstown briefly.

On June 1, 1944, Company “K” returned to Weymouth and boarded the Empire Anvil again with the rest of 3rd Battalion. This time was no exercise. They sailed for Normandy on the afternoon of June 5, 1944.

The 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions would land at Omaha Beach. Peter Caddick-Adams wrote in his book, Sand & Steel: The D-Day Invasions and the Liberation of France:

The primary importance of Omaha was in the fact that it lay between Utah and Gold Beaches — fourteen miles as the crow flies to the former, sixteen to the latter. Linking up with both would be a critical phase in the success of Overlord. […] The quickest of overviews indicates just three platoon-sized resistance nests on the coast capable of interfering with the landings at Utah. The same computation for the five miles of Omaha indicates a much greater density: fourteen equivalent strongpoints, admittedly some unfinished on 6 June, which is why further postponement of D-Day would have spelled disaster.

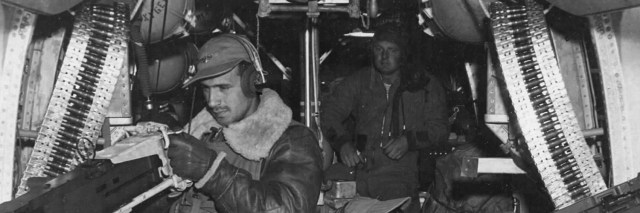

Around 0300 hours on June 6, 1944, the men of Company “K” boarded their landing craft. H-Hour was 0630 hours. M4 medium tanks from the 741st Tank Battalion preceded were supposed to land first, and four companies from the 16th Infantry Regiment scheduled to hit the beach at precisely 0631 hours. Private 1st Class Anderson’s Company “K” was assigned to land precisely 30 minutes into the invasion. The timetable didn’t stay intact for long. Landing craft carrying Company “I” (scheduled in the first wave of infantry) made a navigational error. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Horner, commanding 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, ordered Company “K” to land early.

Affected by strong currents, the company landed at the Fox Red sector under intense machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire. The survivors sheltered sought shelter under a cliff, where the company commander and executive officer were both killed by mortar fire. The next officer who took charge of the company was killed by enemy rifle fire soon after.

In his book, The Dead and Those About to Die: D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach, John C. McManus wrote that “Clearly the cliff offered only temporary shelter.” The was one escape route for what remained of Company “K,” McManus explained:

Only the right, where the cliff gave way to an embankment, incremental bluffs, and a small draw known as Exit F-1, offered any hope. This route would place them directly in the line of fire from [German strong point] WN-60, but there was no other way forward.

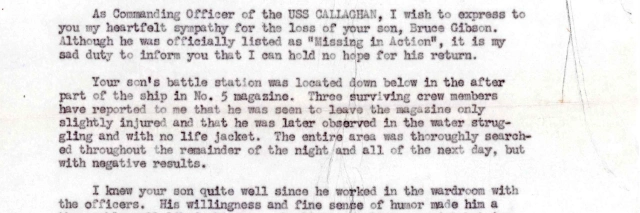

Slowly, all across Omaha Beach, small groups of soldiers advanced—often with the support of what armor had made it to the beach as well as destroyers offshore—and overcame the German positions on the bluffs one by one. The survivors of Company “K” helped overcome WN-60 and open the draw. Casualties were severe. The company morning report for June 6 recorded losses of 12 men killed, 26 wounded, and 23 missing. Of the missing, at least three were killed on D-Day and 13 wounded either on D-Day or soon after.

Private 1st Class Anderson was killed in action sometime on D-Day. According to the digitized hospital admission card under his service number, he was struck in the neck by fragments from an artillery shell.

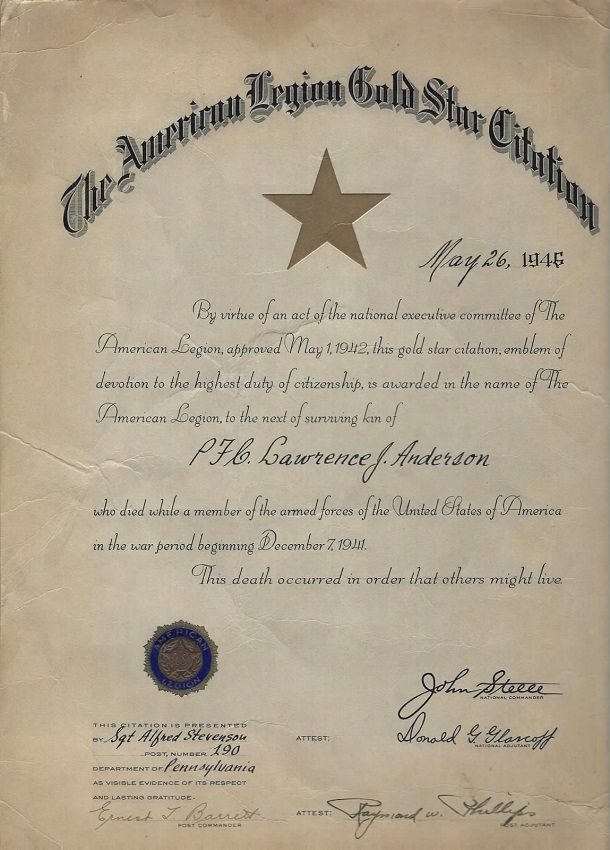

Private 1st Class Anderson was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star Medal, the latter per General Orders No. 113, Headquarters 1st U.S. Infantry Division, dated June 26, 1945. The citation stated:

For heroic achievement in connection with military operations against the enemy in the vicinity of Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. Despite intense enemy machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire, Private Anderson courageously remained exposed to the barrage and, until mortally wounded, fearlessly assisted in moving valuable equipment ashore. Private Anderson’s heroic actions and self-sacrificing devotion to duty contributed immeasurably to the success of the invasion.

On June 13, 1944, Private 1st Class Anderson was buried at the American St. Laurent Cemetery (Plot D, Row 5, Grave 99). After the war, families were given the option of either returning their loved ones’ bodies to the United States or having them buried in a permanent military cemetery abroad. On March 31, 1947, Anderson’s widow signed a form requesting that his body remain abroad. Private 1st Class Anderson’s body was disinterred on October 10, 1947, and reburied in a permanent grave (Plot I, Row 25, Grave 13) at the same cemetery on November 25, 1948. The cemetery is now known as the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial.

Anderson’s wife, Charlotte, remarried and was widowed two more times. She married Harry Ivan Darr (1888–1958) in Alexandria, Virginia on October 8, 1953. After Darr’s death, she married William Charles Walls (1917–1991) in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, on May 29, 1962.

Charlotte’s friend and neighbor Janice Tunell recalls a story from the last week of Charlotte’s life. Janice joked with Charlotte that three husbands would be waiting for her in heaven, asking her: “Which one are you going to choose?”

Janice recalls that Charlotte gave it some thought and then answered: “It would have to be Larry because I didn’t get to spend much time with him.”

Notes

Family

Some records list Julia Anderson’s maiden name as Barns or Barnes, although this may have been Anglicized. Very little information is available about Edward Charles Anderson. He was likely born in Pennsylvania around 1915 with another name. When the elder Lauritz Andersen registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he denied having any dependents including a wife or child under 12. Anderson’s parents married in 1918. Charles Anderson may have been Julia Anderson’s son from a previous relationship.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Janice Tunell for providing the photos and documents which accompany this piece.

Bibliography

Application for World War II Compensation for Charlotte E. Anderson. January 27, 1950. World War II Veterans Compensation Applications. Record Group 19, Series 19.92, Records of the Department of Military and Veterans Affairs. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/3147/images/41226_2421406274_0714-03097

Certificate of Marriage for Harry I. Darr and Charlotte E. Anderson. October 8, 1953. Virginia, Marriages, 1936–2014. Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9279/images/43067_162028006054_0586-00030

Certificate of Marriage for Lawrence J. Anderson and Charlotte Czeslawa Stegnerski. May 3, 1942. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61368/images/TH-267-12696-22474-48

“Charlotte E. ‘Tess’ Walls.” The News Journal, December 13, 2000. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/67184555/lawrence-j-anderson-widow-obit/

“Charlotte Elizabeth Stegnerski.” U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936–2007. Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/23342193:60901?tid=13004207&pid=27581943471

“Charlotte Elizabeth ‘Tess’ Stegnerski Walls.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/34662712/charlotte-elizabeth-walls

Draft Registration Card for Lauritz Andersen. June 5, 1917. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005270400_00150

Draft Registration Card for Lawrence John Anderson. October 16, 1940. WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_09_00001-00129

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4639360_00960

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4313316-00312

“General Orders No. 35, Headquarters 1st Infantry Division.” December 26, 1942. First Division Museum website. https://firstdivisionmuseum.nmtvault.com/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=5d51b39f-52d3-4177-b65e-30b812011812%2Fiwfd0000%2F20141124%2F00000159&pg_seq=1317

“General Orders No. 113, Headquarters 1st U.S. Infantry Division.” June 26, 1945. First Division Museum website. https://firstdivisionmuseum.nmtvault.com/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=5d51b39f-52d3-4177-b65e-30b812011812%2Fiwfd0000%2F20141124%2F00000159&pg_seq=1317

Goldberg, Herbert. “History Medical Detachment 16th Infantry 1st US Infantry Division United States Army November 1940 to May 1945.” July 14, 1945. First Division Museum website. https://firstdivisionmuseum.nmtvault.com/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=5d51b39f-52d3-4177-b65e-30b812011812%2Fiwfd0000%2F20141124%2F00000420

Headstone Inscription and Interment Record for Lawrence J. Anderson. Headstone Inscription and Interment Records for U.S. Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942–1949. Record Group 117, Records of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1918–c. 1995. National Archives at Washington, D.C.https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9170/images/42861_647350_0535-01456

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Lawrence J. Anderson. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

McManus, John C. The Dead and Those About to Die: D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach. Dutton Caliber, 2019.

“Monthly Personnel Roster Aug 31 1941 Med Det 16th Inf.” August 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503_14.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Jul 31 1941 Med Det 16th Inf.” July 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503_14.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Sep 30 1942 Company K 16th Regt.” September 30, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503_05.pdf

Morning reports for Company “K,” 16th Infantry Regiment. June 1943 – June 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Mrs. Julia B. Anderson.” Chester Times, December 3, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/148559375/

“Pay Roll Company ‘K’ Sixteenth Infantry APO #1, U. S. Army For month of August, 1943.” August 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503_04.pdf

“Pay Roll Company ‘K’ Sixteenth Infantry APO #1, U. S. Army For month of December, 1942.” December 31, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503_05.pdf

“Pay Roll Company ‘K’ Sixteenth Infantry APO #1, U. S. Army For month of June & July, 1943.” July 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503_04.pdf

“Pay Roll Company ‘K’ Sixteenth Infantry APO #1, U. S. Army For month of November, 1943.” November, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1503_04.pdf

“PFC. Lawrence J. Anderson.” Newspaper clipping from an unknown paper (probably the area of Chester, Pennsylvania), circa 1944. Courtesy of Janice Tunell.

“Requiem for Boy Parishioner.” Camden Post-Telegram, October 8, 1940. https://www.newspapers.com/article/148554610/

“Seven Are Enlisted For Service in Army.” Journal-Every Evening, November 8, 1940. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/67182306/lawrence-j-anderson/

Tunell, Janice. Phone interview on January 24, 2021, and correspondence on January 24, January 31, and March 20, 2021.

U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/704056902/u-s-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954-blank

Last updated on September 25, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.