This is the most accurate list of Delaware’s World War II fallen yet released. Click below to view in PDF format (used for ease of viewing and updating across multiple platforms).

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 2.1 (October 29, 2025)

Below is an explanation of my methodology in discovering the names on the list, as well as a discussion of the methods and limitations that the Public Archives Commission used in compiling their original lists in the 1940s and 1950s. Finally, older versions of my list are at the bottom of the page.

Who is a Delawarean?

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission (now the Delaware Public Archives) in preserving documentation pertaining to World War II fallen and later making it available to the public. In fact, the abundance of material, including the only known photographs of dozens of fallen soldiers, played a large part in my decision to expand a smaller project chronicling Newark’s World War II dead into what became Delaware’s World War II Fallen.

One of the most challenging parts of this project was determining its scope: who to include, from what organizations, and from what time frame.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, State Archivist Leon deValinger, Jr. (1905–2000) had ultimate authority for determining whether someone should be honored as a fallen Delawarean. Governor Walter W. Bacon (1880–1962) made deValinger point man on an initiative to document those Delawareans who died in the service during the war, in addition to what was already a full portfolio. While I feel I owe a debt to deValinger and his staff for providing a foundation for my own work, as I examined the materials, I found myself troubled by who he decided to include and who he chose to exclude.

The definition I settled on was “anyone who called Delaware home.” Under this definition, a future servicemember who resided in Delaware for any period would qualify. This includes people who lived in Delaware as children or young adults and then moved away, as well as people who lived most of their lives elsewhere but then moved to Delaware shortly before entering the service. One exception is that a student attending college in Delaware but having a permanent address out of state is not a Delawarean, as a college student would not have put roots down in Delaware and would typically consider their permanent address home.

As a result, Delaware’s World War II Fallen includes some names omitted from previous lists such as those published by the Public Archives Commission used in the 1949 In Memoriam: A Memorial Volume Dedicated to those Men and Women of Delaware who lost their lives During World War II and the 1955 War Memorial Monument at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Although there is significant overlap, there are two main differences in definition. First, the Public Archives Commission generally excluded personnel who lived in Delaware if they moved out of state prior to entering the service, though there was much inconsistency on that front. On the other hand, they sometimes included personnel whose next of kin (parents or spouse) lived in Delaware, even if there is no evidence that the servicemember in question ever even set foot in Delaware, much less lived there!

More troublingly, there are many names that would meet both mine and the Public Archives Commission definitions who were left out of the 1949 volume and 1955 wall both due to errors by the archivists and factors beyond their control.

The following table summarizes the differences in definition.

| Residency Status | Delawarean for Public Archives Commission? | Delawarean for this site? |

| Born, raised, and entered service from Delaware | Yes | Yes |

| Born and/or lived in Delaware, entered service from another state | Inconsistent, generally no | Yes |

| Born out of state, moved to Delaware prior to entering service | Inconsistent, generally yes | Yes |

| Never lived in Delaware but had next of kin (wife or parents) who did | Yes | No |

| Attended college in Delaware | Undetermined | No |

Case Studies

A few cases illustrate problematic aspects of the Public Archives Commission policy.

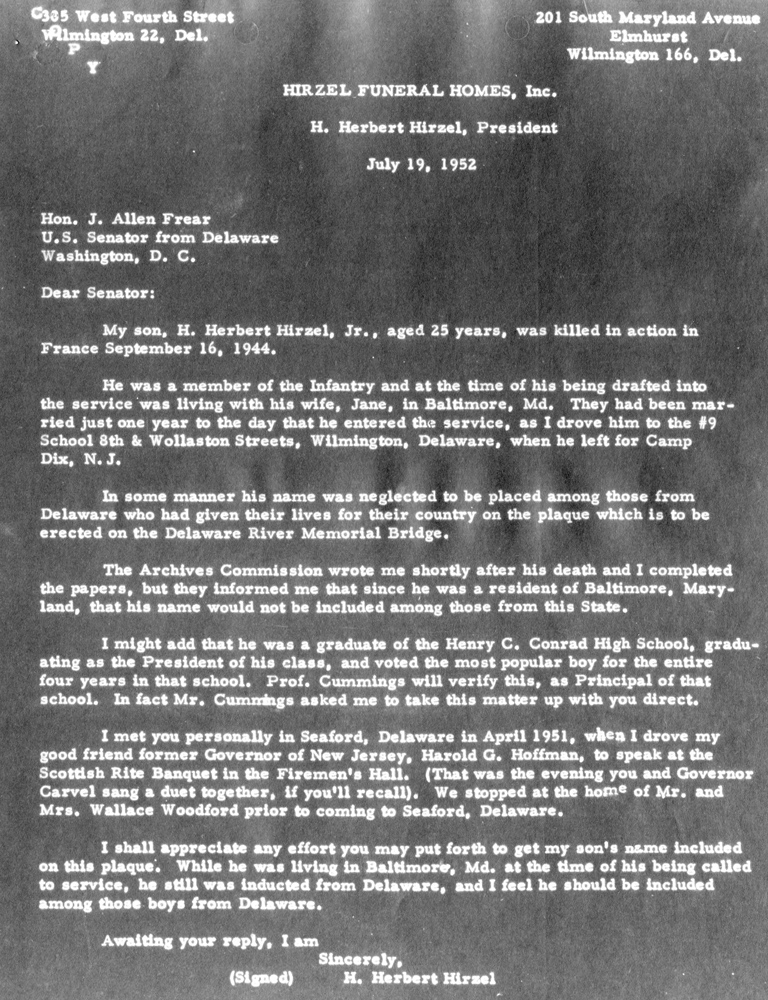

Private 1st Class Howard Herbert Hirzel, Jr. (1919–1944) was born and raised in Wilmington, and lived most of his life there or in the Wilmington suburbs. He graduated from high school in Delaware and attended college there. Sometime between October 16, 1940, when he registered for the draft, and October 19, 1943, when he was inducted, Hirzel married and moved to Baltimore, Maryland. Despite the move, he was drafted by a Wilmington board. While serving with Company “L,” 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division, he was killed in action on September 16, 1944. Although he had lived in Delaware for over 21 years and his parents were still residents of the state, the Public Archives Commission deemed Hirzel “Not a Delawarean” and excluded him from the memorial volume.

However, in 1952, as preparations began for what ultimately became the War Memorial Monument, which honored servicemembers from Delaware and New Jersey who died during World War II and the Korean War, Hirzel’s father began campaigning to have his son’s name included. J. H. Tyler McConnell (1914–1989), then commissioner of the State Highway Department, suggested the state archivist reconsider, arguing in a letter dated August 6, 1952:

In this, and other close cases, I personally feel very strongly that we would be wise to include rather than exclude names of deceased veterans who have a logical connection with the states of Delaware or New Jersey. The recognition is a relatively minor thing and I would certainly urge that, wherever possible, we avoid in any way hurting the feelings of persons who have lost a son or relative in the war, particularly when the case has been specifically called to our attention in advance.

Eight days later, deValinger conceded that “These border-line cases are always difficult to decide, and probably the best solution is a compromise.” He agreed to have Hirzel honored on the memorial. The elder Hirzel’s success in overturning the original judgement of the state archivist was the exception, though, rather than the rule.

Sergeant William H. Dean, Jr. (1913–1944) was born and raised in Newark, Delaware. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1933. After his discharge in 1937, he settled in New Jersey and married. He was still living in New Jersey when he was recalled to duty in 1943. Though Dean, like Hirzel, had moved out of state and married, and had been a resident of New Jersey for at least twice as long as Hirzel had been a resident of Maryland, deValinger raised no objection to Dean being classified as a Delawarean.

Water Tender 1st Class Herbert H. Dugan (1911–1942) was also born and raised in Delaware. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1929. After he was honorably discharged in 1935, he settled in Washington state with his wife. He reenlisted in 1942 and was killed in action that same year. Dugan had not resided in Delaware in over 13 years at the time of his death, and he lived with his family in Washington for nearly seven years before reenlisting, but deValinger raised no objection to Dugan being classified as a Delawarean.

Captain William Osmond White, Jr. (1920–1945) was born in Savannah, Georgia, and lived in Georgia and possibly South Carolina before entering the service. White earned the Bronze Star in Normandy and was later wounded there. He returned to duty several months later and on Christmas Eve 1944 assumed command of Company “A,” 134th Infantry Regiment, 35th Infantry Division. During the Battle of the Bulge, he was wounded and captured. He died of his wounds on January 19, 1945.

After White joined the U.S. Army in 1942, his parents moved to Newark, Delaware. His parents even told the Public Archives Commission in 1946: “As you can see our son never lived in Delaware.” However, deValinger replied to this disclosure by pointing out:

In filling out the form you also pointed out that your son never lived in Delaware and that you have been residents for only three years. May I add, however, that one year establishes you as a resident of the State and, if your son claimed his residence with you, he would in that three years’ period have been entitled to residence in Delaware. Also, if he had returned it is probable that he would have made his residence here.

So, although White was never a Delaware resident, and his parents made no particular effort to have him honored there, deValinger included him in both the memorial volume and at Veterans Memorial Park.

However, deValinger did not approach the family of Aviation Radioman 3rd Class George A. Quigg (1924–1944) with similar care. Quigg’s mother’s 1947 letter to the Public Archives Commission makes it clear that she was confused about the definition of Delawarean:

In reply to your letter, inquiring as to whether or not my so[n] George was a native Delawarean, I wish to inform you that although he was employed with the Atlas Powder Company in Wilmington Delaware, and entered from there, he was not a native of that state.

He was born and brought up in Pennsylvania and just happened to be working in Delaware when it was time for him to enter the service.

The letter makes it clear that, unlike White and Dean, Quigg was living and working in Delaware when he joined the military. The state archivist did not inquire whether Quigg had been living in Delaware for a year or longer, nor did he inquire about Quigg’s mother’s residency status during the war. He did not point out that whether or not Quigg was a Delaware native was irrelevant to the list the Public Archives Commission was compiling, which included many people who were not born in Delaware. Instead, he thanked her for explaining “that your son was not a Delawarean” and stated: “We are accordingly removing his name from our list as he will rightfully be listed from Pennsylvania.”

Surviving documentation in Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II at the Delaware Public Archives indicates that deValinger was preoccupied with the notion that a servicemember should be honored in one and only one state. This may explain certain decisions in borderline cases.

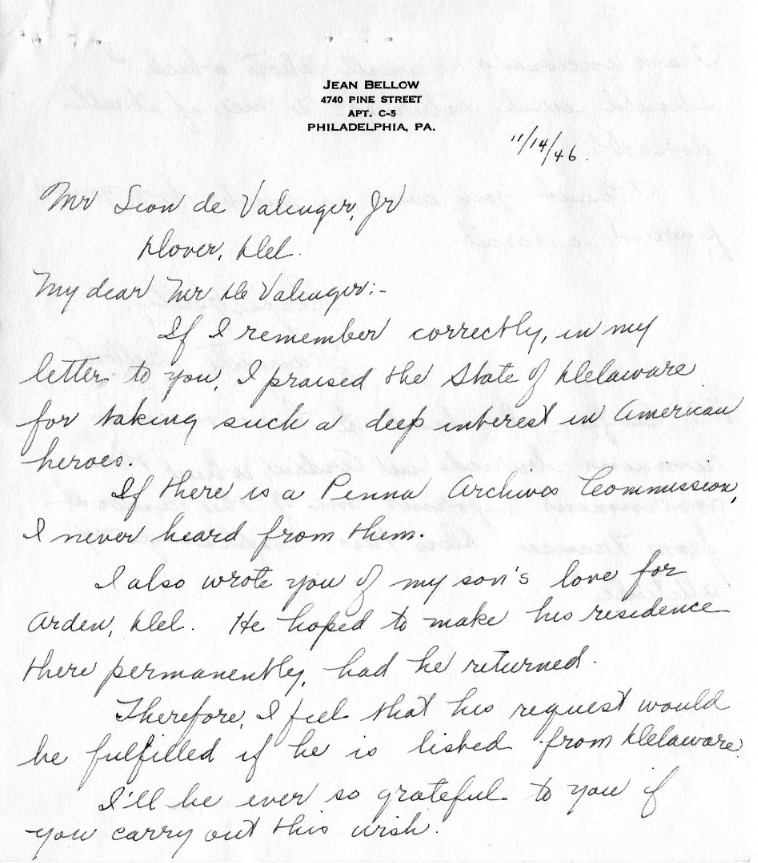

In the case of Private 1st Class Hirzel, Maryland authorities told deValinger that he would be included in their honor roll. Authorities in Georgia acknowledged receiving deValinger’s inquiries about Captain White in 1949, but it appears that they did not give him a response about whether they would be honoring White in that state. Another man who was included in the Delaware memorial volume and at Veterans Memorial Park was Private Louis Waldo Bellow (1924–1944). By any definition, Bellow was a Pennsylvanian, albeit one who spent his summers in Arden, Delaware. In 1946 correspondence with Bellow’s mother, deValinger expressed concern that “if he is also claimed officially as a Pennsylvanian, we would be including in our Volume one who should appear from Pennsylvania rather than from this State.” However, he was satisfied when she assured him that: “If there is a Penna Archives Commission, I never heard from them.”

It is unclear why deValinger was opposed to servicemembers with connections to multiple states being honored in more than one, especially since not every state would necessarily honor its fallen in a statewide publication or memorial. He also seems not to have considered the possibility that by removing those men who his staff were unable to confirm were Delawareans, there was the risk that some men would not be honored anywhere.

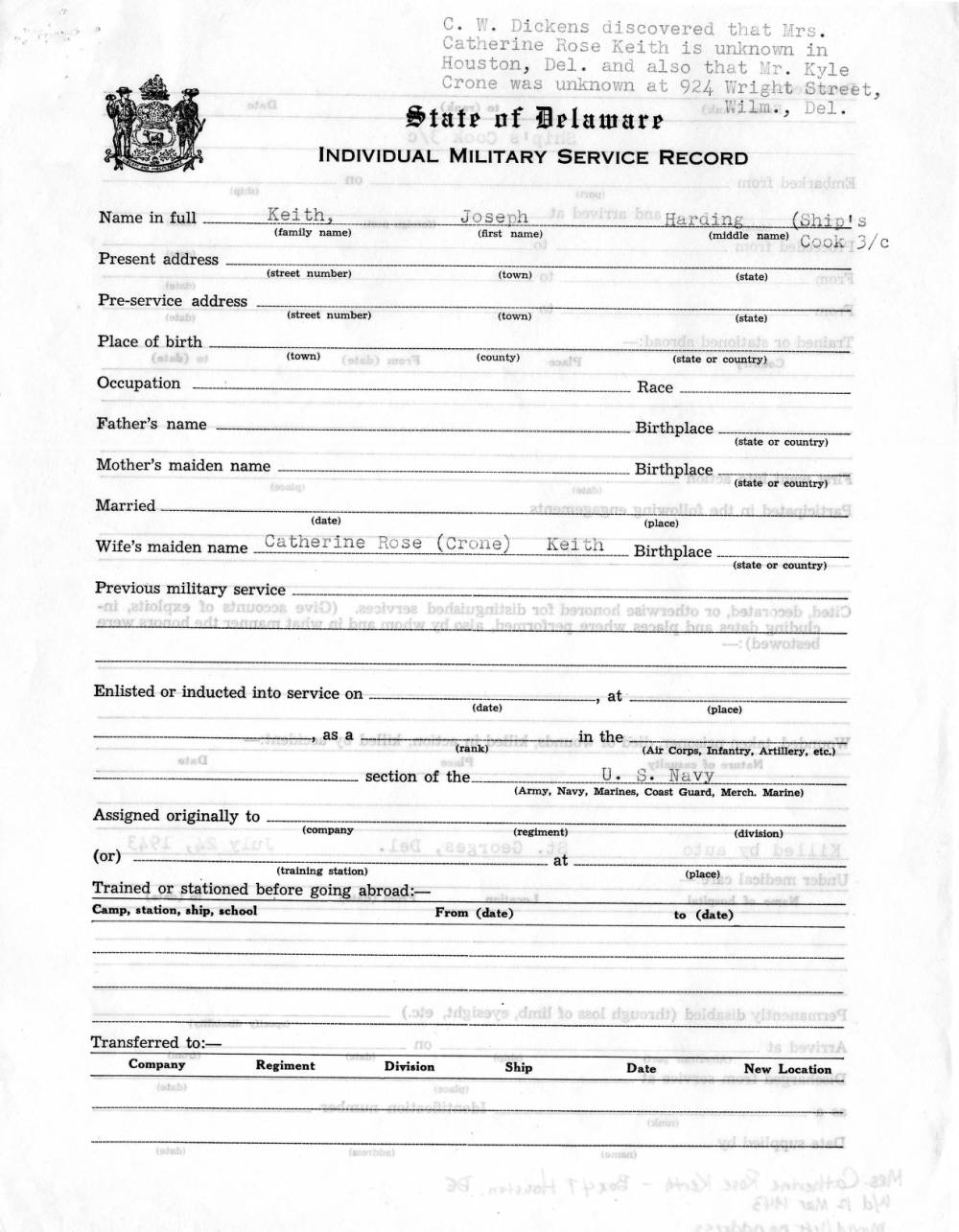

One such case is that of Private Fred R. Prattis (1912–1944), who apparently lived his entire life in the area of Seaford, Delaware, until he was drafted. The Public Archives Commission did have his name from a U.S. Army casualty list, but his file only notes that “C. W. Dickens could not locate the next of kin Oct. 7, 1949[.]” My preliminary research indicates that black servicemembers like Prattis were about three times more likely than white personnel to be omitted by the Public Archives Commission.

Curiously, deValinger and his staff did not make full use of the potential resources available at the time, at least not to research everyone. Private James Joseph Giletti (1906–1945) did not appear on any official list of fatalities, because he was medically discharged from the service after a severe line of duty injury in 1944. The following year, he apparently died of complications from those injuries. Yet deValinger took the extra step of contacting the local Selective Service headquarters, who confirmed his home address and dates of service. This was admirable and it is entirely due to his diligence that Giletti was honored at all. On the other hand, there is no evidence such a step was taken with Private Prattis or with several other Delawareans who were excluded due to inability to contact their next of kin.

I cannot fault the state archivist for having a different definition of Delawarean than I do, but these cases illustrate the inconsistency both in who he considered a Delawarean and the steps he used to confirm the candidates. Thus, my site errs on the side of inclusion, similar to the approach advocated by J. H. Tyler McConnell.

What Branches Are Included?

That members of the U.S. Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard are covered is obvious. The Public Archives Commission also included a number of other men whose sacrifice would have otherwise gone unrecognized, since there are no readily available state casualty lists for them. This includes members of the Merchant Marine, civilian employees of the armed forces, members of the Civil Air Patrol, and an officer in the Coast and Geodetic Survey.

What Dates Are Covered?

Deciding on a timeframe was less straightforward. Possible start dates include July 7, 1937, arguably the beginning of World War II in Asia; September 1, 1939, the beginning of World War II in Europe; May 27, 1941, when President Roosevelt declared an unlimited national emergency; and December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor, which precipitated American entry into the war. Possible end dates include August 14, 1945, when the surrender of Japan was announced; September 2, 1945, when representatives signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender; and December 31, 1946, when President Truman officially proclaimed the end of hostilities.

The earliest death the Public Archives Commission included was October 7, 1940, and the latest was June 27, 1948. (There was also a sailor who died during the Korean War was erroneously listed in the World War II section of the Delaware War Memorial.)

I made an arbitrary decision to focus on Delaware fallen between December 7, 1941, and September 2, 1945. That said, I have already profiled two men who died after this time. I also intend to profile others whose deaths were related to their wartime service but who died after September 2, 1945, and won’t rule out expanding the timeframe in the future.

Sources of Names

With the scope established, the next question was how to learn the names of those World War II fallen I would be profiling. I entered each particular candidate into a database and then evaluated whether they met my criteria. As of November 2, 2025, I have evaluated 913 names, of whom 785 I consider to be fallen Delawareans who died during the war or in connection with injuries received during wartime.

Delaware Memorial Volume

The Delaware memorial volume, formally titled In Memoriam: A Memorial Volume Dedicated to those Men and Women of Delaware who lost their lives During World War II, was completed in 1949 and was long the most authoritative list of Delaware’s World War II fallen. It features the name and a paragraph about each fallen servicemember whose identity as a Delawarean was accepted by the state archivist. The volume is unfortunately riddled with errors, in part because it was based on information supplied by families during and immediately after the war, when limited information was available about their loved ones. A handful of families also intentionally provided deceptive information to the Public Archives Commission, apparently due to feelings of shame over various facts such as causes of death being suicide or even cancer.

This source provided me with 781 men and women, of whom at least 728 I consider to be fallen Delawareans.

Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II

To obtain information, the Public Archives Commission identified candidates from official casualty lists and newspaper articles and distributed questionnaires to the families and requested photos. Although they later determined it was impractical to incorporate photos into the printed volume, they proved invaluable in illustrating articles on my site. In recent years, the Delaware Public Archives digitized these files and put them online. These files included many people that the Public Archives Commission determined were not Delawareans, but who I later determined did meet the criteria.

This source provided an additional 13 names, of whom I consider 10 to be fallen Delawareans.

State Summary of War Casualties [Delaware]

In 1946, the Navy Department released a list of casualties beginning on December 7, 1941, covering the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. The Navy’s curatorial decisions were very strange indeed. First, they restricted the list to those which occurred overseas, while “Casualties in the United States area or as a result of natural causes, homicide or suicide in any location are not included.”

For instance, an aviator who died in a plane crash in the South Pacific would be included, even if not caused due to enemy action, whereas an identical crash in a training accident in or near the continental United States would be omitted, as if those men’s lives were not equally worthy of commemoration.

The second problem with this source is that although it was organized by state, the casualty was listed under the residence of their next of kin, not their residence upon entering the service. Thus, a Delawarean who met a woman in Maine during his service and married her was listed on the Maine casualty list. Similarly, a Marylander whose parents lived in Delaware was listed on the Delaware casualty list. This decision in particular had far reaching effects. The original 1955 memorial in New Castle commemorating Delaware and New Jersey fallen even omitted the famed New Jerseyan Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone (1916–1945), a Medal of Honor recipient. His name appears on the California casualty list because of where his wife lived. Though his name was subsequently added to the memorial, it is virtually certain that many other lower profile servicemembers remain unidentified. The reason for this decision is unclear. Every Navy personnel file recorded home address, state of residence, and even congressional district of residence.

This is one source that the Public Archives Commission had access to when compiling their own list, and indeed it seems to be responsible for the inclusion of several people who never lived in Delaware. This source provided no new names beyond what was covered in the memorial volume. If the Army casualty list is any indication, there are Navy Department Delawareans that both the Public Archives Commission and I have missed.

World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing State of Delaware

In June 1946, the War Department released official state casualty lists, including one for Delaware. It included U.S. Army personnel (including the Army Air Forces) killed between May 27, 1941, and January 31, 1946, as well as men still considered missing in action at the end of that timeframe. The list is superior to the U.S. Navy list for several reasons. First, it is organized personnel by county based on home address upon entering the service, except when no address was disclosed, though sometimes a man was entered under residence of his next of kin if he did not disclose an address upon enlistment or induction. Second, the list contained all soldiers who died in the service, regardless of whether that soldier was killed overseas or stateside, and regardless of whether the death was from combat or non-battle causes.

The compilers noted:

As in any work of this scope, errors will occur. Careful checks by the Casualty Branch of The Adjutant General’s Office and by Machine Records Units have reduced these errors to a minimum, but publication of this preliminary report at this time makes it inevitable that mistakes and omissions will be found here in. […] It is planned to publish a complete and final list of deaths at some time in the future, and errors discovered herein will be corrected in that list.

Unfortunately, it appears that no such complete and final list was ever published.

The Delaware list features 579 names, including 87 names not included in the memorial volume or Record Group 1325-003-053. I determined that at least 38 of these men were indeed Delawareans, though many of them had lived in the state for a relatively short time prior to entering the service. The Public Archives Commission had access to this list when compiling their memorial volume. They wisely treated it with caution, since as the compilers warned it was full of errors. I determined that 39 of the new names were not in fact Delawareans but rather residents of other states or countries.

Oddly, the Delaware list also includes two British men living in the Philippines when the Pacific War began who were commissioned into the U.S. Army. This may be due to how residences were coded. The list also included an elderly retired soldier who died of natural causes during the war, plus at least one and likely two men who survived as prisoners of war.

Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency

When I began this project, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency maintained lists of servicemembers from World War II who remain unaccounted for, arranged by state. Although these state level lists are no longer readily available, they provided an additional nine names, of whom at least seven meet the criteria. Fortunately, U.S. Navy personnel were listed by state of residence and not by residence of next of kin.

Veterans Memorial Park

Although most names featured on the Delaware War Memorial at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle were covered in the Delaware memorial volume or in Record Group 1325-003-053, there were an additional nine names listed not included in those sources. Only two of these names meet the criteria. One name was erroneously included in the World War II section instead of the Korean War section. Another, Lynam Le Roy, is more mysterious. I can find no evidence this person ever existed, much less lost his life in the service during the war.

During 2024–2025, there was a renovation and expansion done at the Delaware War Memorial, most notably adding names from conflicts after the Korean War. Unfortunately, the Delaware River and Bay Authority did not consult Delaware’s World War II Fallen. The World War II section of the new memorial did not add any names except two apparent duplicates. While the fictitious Lynam Le Roy remained intact, two names that were correctly included in 1955, Sergeant Joseph Harold McGinley (1918–1942) and Private 1st Class Joseph Aloysius McGrath (1911–1944), mysteriously disappeared.

Tips

Four names were submitted by readers or other researchers, including Private Robert D. Henderson (1923–1944), who was nominated by another member of his platoon, the late Jim Sterner (1923–2024).

Other

The Middletown Honor Roll provided two new names, while the Newark war memorial provided one name. I discovered two names in a DuPont Company publication, Threadline, two names through the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware’s honor roll, one name through the Stories Behind the Stars D-Day project, and came across one name by chance in a historic newspaper article.

Vetting Names

Evaluating whether someone was a Delawarean is not always straightforward. I typically start with genealogical websites. Census records can be useful but only provide snapshot glimpses once a decade. Delaware birth certificates are readily available but are incomplete especially before 1913 and sometimes have mangled names, especially for Delawareans whose parents were immigrants. The Wilmington directories were completed every two years but are only useful for people who lived in that city and whose names are distinctive enough. Draft registration cards are a valuable source since they often were updated with addresses when someone moved. Newspaper articles are often available but sometimes have errors. U.S. Army enlistment data cards provide county of residence but are sometimes garbled. Individual deceased personnel files (I.D.P.F.s) are readily available and often record city of residence at entry to the service. Official military personnel files (O.M.P.F.s) typically record residence at entry into military service, but Army ones were largely destroyed in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire and the other branches can be expensive to obtain.

It can be difficult to say with certainty that someone was not a Delawarean and like the Public Archives Commission, sometimes I make mistakes. I originally excluded a Marine officer, Francis Hubert Williams (1906–1945), who the Public Archives Commission included. He was born in Florida, and the usual sources established that he also lived in Colorado and entered the service from Pennsylvania. I was not able to find him in the 1920 census. Initially I concluded that he had been included by the Public Archives Commission because his wife was a Delawarean. However, I overlooked newspaper articles that established that he graduated from Wilmington High School in 1924 and lived in Wilmington until around 1925.

Of the 913 names I have investigated, there 32 names in my database whose residency status is ambiguous. In descending order of likelihood, I have used the following labels: probably, possibly, unclear, and doubtful. It can be hard to prove a negative. Someone recorded on the census in Maryland in January 1920 could have moved to Delaware in February and then back to Maryland in March 1930 before the next census and there would be no indication they had moved at all. It is an ongoing and time-consuming process that due to limitations in available records and my own time and research abilities will never be perfect!

Older versions of the list:

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 2.0 (May 26, 2025)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.9 (December 19, 2024)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.8 (August 30, 2024)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.7 (May 4, 2024)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.6 (December 16, 2023)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.5 (September 15, 2023)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.4 (June 4, 2023)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.3 (March 25, 2023)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.2 (December 28, 2022)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.1 (August 19, 2022)

Delaware’s World War II Fallen List Version 1.0 (May 31, 2022)

Last updated on December 12, 2025

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.