| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Frederica, Delaware | Laborer for a construction company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 12014092 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Zone of Interior (American) | Attached unassigned to 715th Training Group |

Early Life & Family

Charles Raymond Wilson was born in rural Milford Hundred, Kent County, Delaware, on the afternoon of July 16, 1921. He was the third child of Raymond C. Wilson (a laborer, 1895–1957) and Beatrice Wilson (née Carey, 1898–1972). It appears that his oldest sibling was stillborn or died very young. He grew up with an older sister, Elizabeth Marie Wilson (1917–after 1998).

Wilson was recorded on the census in April 1930 living with his parents and sister on Saint Agnes Street in Frederica, Delaware. His father was a road construction laborer at the time. On May 29, 1939, Wilson applied for a job with the George and Lynch Construction Company in Wilmington, Delaware. The next census in April 1940 found Wilson living with his parents and cousin on David Street in Frederica.

Although the 1940 census stated that Wilson had only completed the 8th grade, his enlistment data card from the following year described him as a high school graduate. His occupation was “semiskilled chauffeurs and drivers, bus, taxi, truck, and tractor,” while his family’s statement for the Public Archives Commission described him as a laborer.

A physical dated November 17, 1942, described Wilson as standing five feet, nine inches tall and weighing 149 lbs., with blond hair and green eyes.

Military Career

Wilson reportedly served a three-year term in the National Guard before being honorably discharged. He later volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Corps in Dover, Delaware, on March 17, 1941. One advantage of enlisting prior to the U.S. entry into World War II was that soldiers could not only choose their branch of service but even be enlisted for a specific unit. The Wilmington Morning News reported that Wilson was one of six men who enlisted in the U.S. Army “at the Dover office setting a record for one day’s enlistments there.” The paper reported that Wilson and three others would be joining the 33rd Pursuit Group at Mitchel Field, New York. “Pursuit” was an old term for what eventually became known as fighter aircraft. During the war, pursuit units were redesignated as fighter units, though the P- prefixes used for various models of fighters (e.g., P-51 Mustang) were retained until after the war.

At 0600 hours on March 18, 1941, Private Wilson joined the 58th Pursuit Squadron, 33rd Pursuit Group. His military career got off to a rocky start. He was reported absent without leave (A.W.O.L.) at 0600 hours on June 23, 1941, officially returning to duty at 0600 on July 7. He went A.W.O.L. again during August 1–4. On August 5, he and a group of men were placed on special duty with Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, 33th Pursuit Group “for duration of maneuvers” which in the event the squadron did not depart for until August 28.

On August 28, 1941, Private Wilson transferred to and joined the 306th Materiel Squadron, probably at Mitchel Field. Squadron morning reports note that the men attended a speech by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (1867–1950) at the base’s theater on September 10, 1941, and a picnic held by the 2nd Air Base Group at Islip, New York, on September 13. According to morning reports, Wilson went on furlough during November 17–22, 1941, and on detached service to Floyd Bennett Field, New York, on December 13. He returned to duty at Mitchel Field on January 26, 1942.

Private Wilson was unhappy in his new unit as well, leading to a series of events that had him facing both dishonorable discharge and hard time in prison. 1st Lieutenant Robert McFarland Mouk (1909–1968), assistant provost marshal as well as the police and prison officer at Fort DuPont, Delaware, later testified that Wilson told him:

On January 13, 1942 he was examined for flying cadet training at Mitchel Field and on the 19th or 20th of that month, he arrived at Maxwell Field, Alabama for flying cadet training. He further stated that on the 29th of January, he was released for a physical condition and sent back to Mitchel Field. He returned to Mitchel Field and stayed three or four days and was released awaiting discharge[.]

It is doubtful that Private Wilson was a candidate for aviation cadet, given that 306th Materiel Squadron morning reports mention only the detached service at Floyd Bennett Field, but his claim that he was released from active duty for medical reasons was false. Mouk testified that Wilson changed his story, admitting:

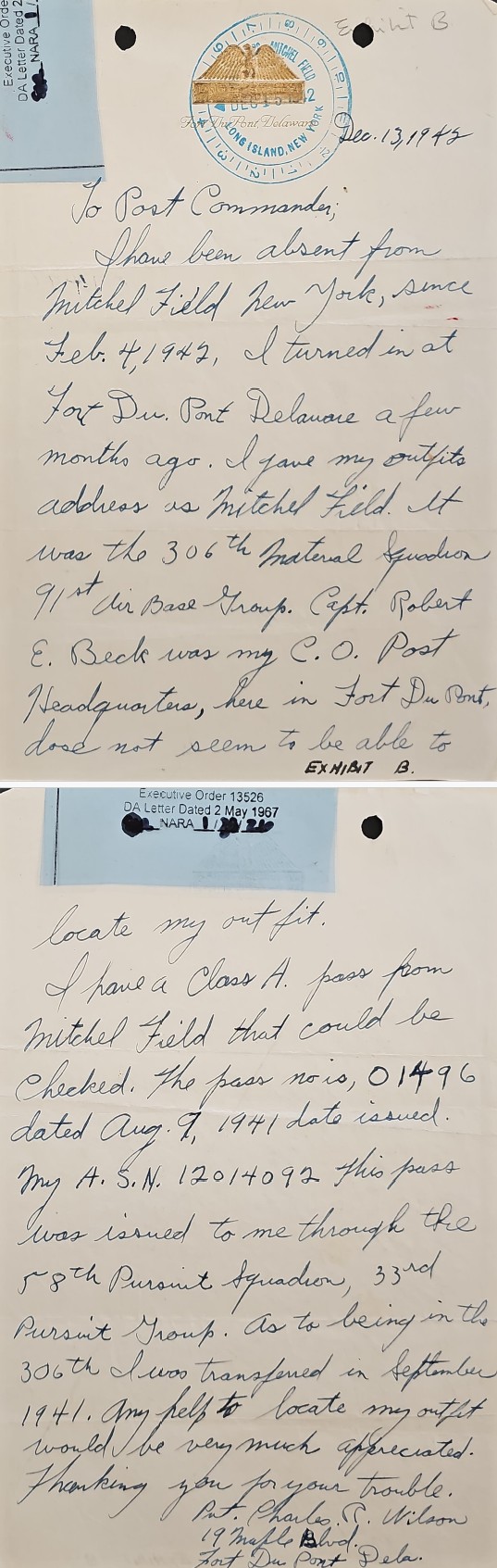

He stated that on February 4, 1942 about 1900 he left his organization without a pass or discharge of any kind. He made up the ‘temporary release’ himself on a form he had secured from the office where he worked. He said, he could not get along with his outfit so he left. He had tried to transfer and couldn’t so he transferred himself out.

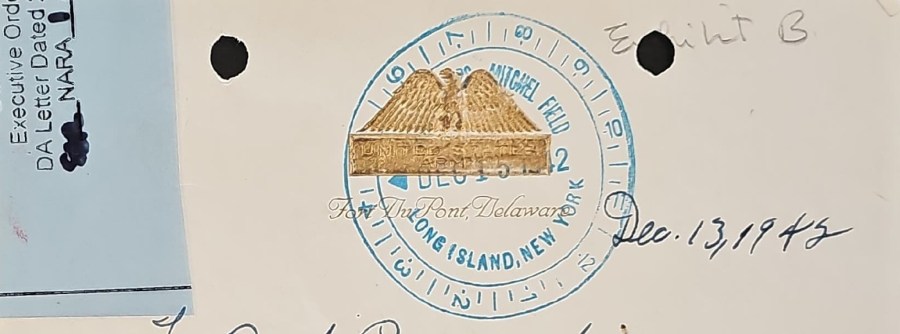

Private Wilson was reported A.W.O.L. again on the morning of February 5, 1942. A subsequent morning report dated February 17 stated that Wilson was deemed a deserter as of February 5. Major H. S. Miller, assistant staff judge advocate at Headquarters Second Service Command, later noted in his instructions to the trial judge advocate prior to Wilson’s subsequent court-martial that: “The court should be cautioned that the entry of February 17, 1942, dropping the accused in desertion, is administrative and may not be used to prove desertion but only continued unauthorized absence on that date.”

By February 21, 1942, Wilson had returned to his former employer, George and Lynch Construction Company, and worked on a project in Greensboro, Maryland, through the week ending May 16, 1942.

Interestingly enough, Wilson ended up doing quite a lot of work on military airfields while on the lam. His next project was at Dover Municipal Airport, Delaware, the field later known as Dover Army Air Base and eventually renamed Dover Air Force Base. He worked long hours there, as many as 55 hours per week, through the week ending July 25, 1942. He then moved on to a new project at the Delaware Park Racetrack in Stanton, Delaware, through the week ending September 26, 1942. Then, once again, he was assigned to another military project, this one at New Castle Army Air Base south of Wilmington, Delaware. The start of the project involved long hours, with one week entailing 58 hours of work, though Wilson’s hours tapered off toward the end of October.

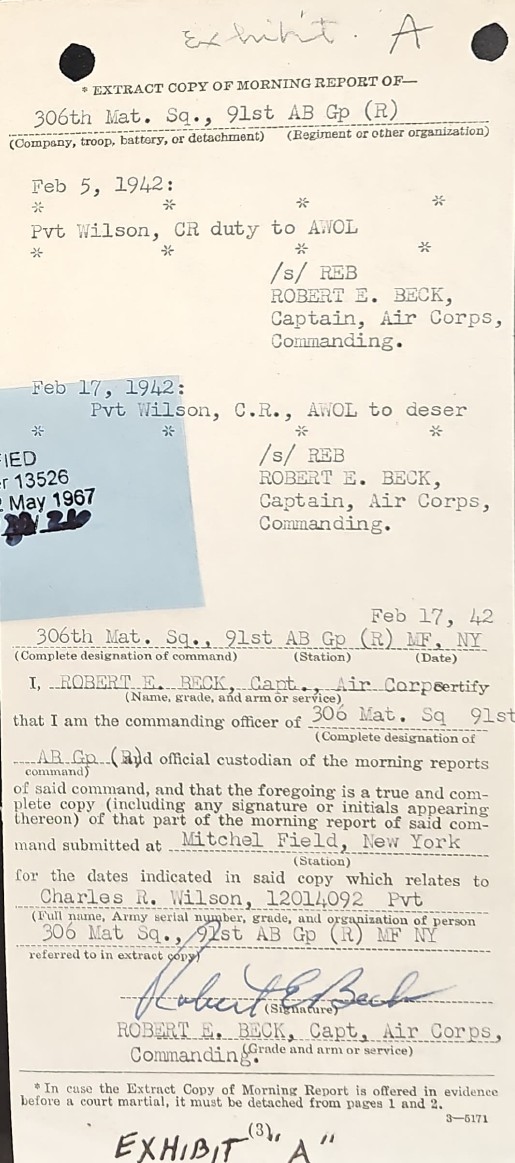

Sometime in 1942, the U.S. attorney for the District of Delaware in Wilmington received a tip that a Charles R. Wilson of Frederica had not registered for the draft. The investigation was eventually turned over to Federal Bureau of Investigation (F.B.I.) Special Agent Shirley “Del” Delbert Coy (1913–1996). Coy called Wilson’s employer to ask Wilson to come in for an interview in Wilmington, which he did on October 27, 1942.

Coy later testified that Wilson claimed

that he had been given a ‘temporary discharge’ from the Army, but he could not produce it, and had kept it in his automobile, and had lost it; however, he produced a sheet of paper which appeared to be an army pass. This pass said, in part, that Charles R. Wilson, 12014092, 306th Tech Supply has permission to be absent from his duties from 6.00 p.m. Feb. 4, 1942 until further notice; and on the bottom was written, ‘waiting for discharge’. I asked him if this was not unusual and he said he had been transferred from Maxwell Field, Montgomery, Alabama, due to a bad heart, and his expenses were paid home to Wilmington.

Special Agent Coy began checking the story, but Private Wilson must have felt it inevitable that his deception would be uncovered. He surrendered to military authorities at Fort DuPont on November 17, 1942, and was placed in confinement in the guard house. Authorities had difficulty getting in contact with Wilson’s old unit to verify his status. Colonel George Ruhlen (1884–1971), commanding officer at Fort DuPont, wrote that due to orders from the commanding general, Second Service Command, “directing release of untried prisoners in confinement in excess of 15 days” Wilson was allowed to leave the guard house on December 28, 1942, though he was ordered not to leave the post.

Special Agent Coy visited him there, later testifying:

I interviewed this boy again on January 13, 1943. During this interview the accused advised, that on February 4, 1942, he had left his squadron on ‘temporary pass’ which he had filled out himself. He admitted to me that he had deserted from Michel Field, New York, and had written out his own pass. He had signed the Company Commander’s name to this pass permitting him to leave. He stated that he got on a train and paid his own expenses and came to Frederica, Delaware, and told his parents that he had been given a ‘temporary release’ to explain his presence at home.

Since Private Wilson was under military jurisdiction, the U.S. attorney instructed the F.B.I. to end its investigation.

Although still restricted to Fort DuPont, sometime that month Private Wilson walked down to the gate and asked a guard to get him a ride to Wilmington. On January 23, 1943, after he was apprehended or turned himself in, Private Wilson was placed back in the guard house at Fort DuPont, Delaware, where he remained until trial. Curiously, he was never charged in connection with this escapade.

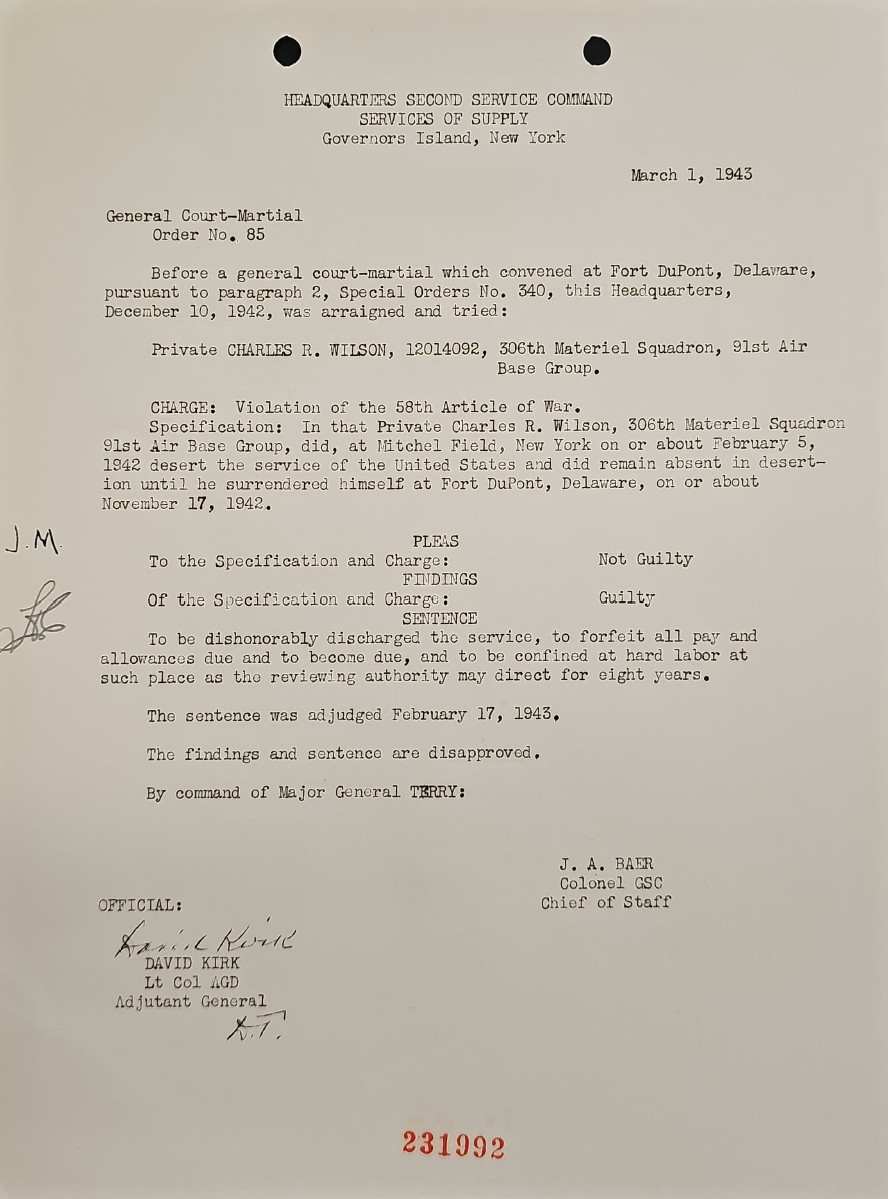

On the evening of February 17, 1943, Private Wilson was tried by general court-martial at Fort DuPont. He pled not guilty to the single charge, violation of the 58th Article of War, desertion during the period of February 5, 1942, through November 17, 1942. He was convicted and sentenced “To be dishonorably discharged [from] the service, to forfeit all pay and allowances due and to be become due, and to be confined at hard labor at such place as the reviewing authority may direct for eight years.” The entire trial had lasted just 75 minutes.

However, in a review completed on February 27, 1943, Major H. S. Miller, assistant staff judge advocate at Headquarters Second Service Command, identified several “errors and irregularities” including two “fatal to the conviction[.]” The extract copy of the 306th Materiel Squadron morning report listing Wilson as A.W.O.L. and as a deserter was read to the court but Miller noted that it was “apparent that this document was not marked in evidence at the trial.” In addition, “Neither employment application nor payroll record was introduced in evidence. There is no proof as to the authenticity of the so-called copy of the payroll or the correctness of the figures or dates.” Miller “recommended that the findings and sentence be disapproved.” Colonel Paul S. Jones, staff judge advocate, concurred and the conviction and sentence were thrown out on March 1, 1943.

Private Wilson was not retried. Instead, he got another chance. He was released from confinement on March 4, 1943, and later attached unassigned to the 715th Training Group, Basic Training Center No. 7, Army Air Technical Training Command, Atlantic City, New Jersey.

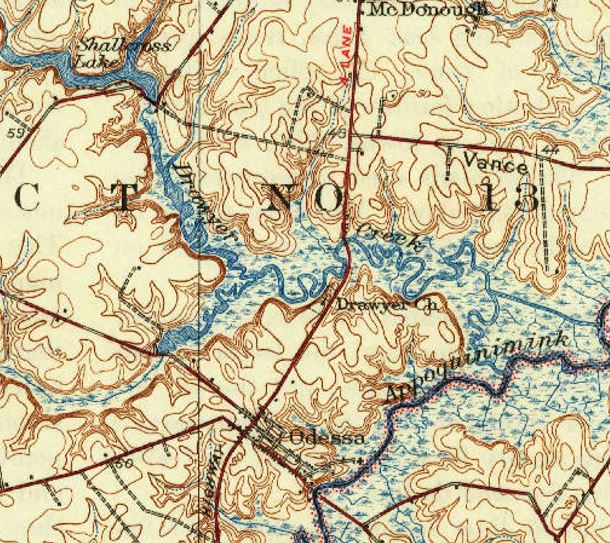

On the night of Saturday, April 24, 1943, Wilson was driving on U.S. Route 13 in Delaware not far from home when he had an accident. The Wilmington Morning News reported: “State police stated that Wilson missed a curve and the car went into Drawyer’s Creek, a short distance north of Odessa.” Although the paper stated that he rushed to the Delaware Hospital in Wilmington by “the country ambulance,” he “was pronounced dead on arrival there” shortly before midnight. According to his death certificate, the crash had fractured his skull and caused a fatal subdermal hematoma. His Adjutant General’s Office report of death, on the other hand, stated he died of a ruptured liver and associated hemorrhage.

Wilson’s last pay voucher stated his death was not in the line of duty under Article of War 107. Unfortunately, the document does not reveal the specific reason. That article covered absences without leave, use of drugs or alcohol, and disease or injury due to the soldier’s own misconduct, all three of which are plausible in the context of his car accident. His personnel file would likely have disclosed the reason but was destroyed in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire.

Unit morning reports list Wilson’s status as duty prior to his death. Brief absences, on a weekend pass for instance, were not recorded in morning reports, but longer furloughs were. A morning report would also have recorded if Wilson was away from Atlantic City due to detached service or a temporary duty assignment. Had Wilson gone A.W.O.L. again, even if his absence was not noticed prior to word getting back to his unit of his death, most likely the clerk would have recorded his status as duty to A.W.O.L. to died. That would suggest that Wilson was on authorized pass, but that the military considered his death as due to substance abuse or other misconduct (e.g., driving under the influence).

Wilson was buried at Barratts Chapel Cemetery in Frederica. His parents were also buried there after their deaths. Wilson is honored on the Wall of Remembrance at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Photo Irregularities

The photograph in Wilson’s file at the Delaware Public Archives is very puzzling indeed. It depicts a soldier wearing the U.S. Army’s enlisted men’s winter service uniform. The man is wearing corporal’s stripes but no visible unit insignia. Details of the uniform including the cap, brown tie, and lack of a belt indicate that it was most likely taken after February 1942. There is no evidence in morning reports that Wilson was promoted at any time during his career, nor is it likely that a soldier who deserted for nearly a year would have been promoted to become a noncommissioned officer soon after being released from confinement. One possibility is that the photo depicts someone other than Wilson. If it is him, he must have been wearing someone else’s uniform or a doctored one.

Another Charles R. Wilson

After Wilson deserted, an oddity in U.S. Army records seems to suggest he had been promoted and assigned to a secret mission.

Effective March 21, 1942, a Sergeant Charles R. Wilson, supposedly with the same service number, 12014092, was attached to the Cedar Project, joining a 50-man Army Air Forces detachment that shipped out from the Charleston Port of Embarkation aboard the U.S.A.T. Monterey that day. How was that possible, if Wilson was a deserter? The Cedar Project was part of a secret effort to supply the Soviet Union through Iran. At first glance, this was the stuff of spy films, suggesting Wilson’s desertion was faked so that he could be assigned to the secret mission or if he did desert, that he was offered the opportunity to redeem himself by volunteering for a dangerous mission.

Secrecy limited what the morning reports recorded about Sergeant Wilson’s detachment. It recorded that they arrived at “Port X” on the afternoon of April 3, 1942; departed there on April 7, 1942; arrived at “Port XY” on April 18, 1942; departed there on April 21, 1942; arrived at “Port XYZ” on April 23, 1942; and departed there on April 30, 1942. Based on the length of the journey and Axis strength in the Mediterranean Sea at that time, it appears that Monterey took a longer journey via the Cape of Good Hope (or less likely, via the Pacific).

The following month’s morning reports were somewhat less secretive, disclosing that the detachment was at sea aboard Monterey until arriving at Abadan, Iran, on the afternoon of May 17, 1942. During the next five days, the men “Worked ashore making preparations for movement to camp site” but remained quartered on their ship until May 23. Sergeant Wilson remained in the Middle East and was promoted to staff sergeant even after Private Wilson returned to military control in the United States. His units included Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, 82nd Air Depot Group.

A roster reveals that Staff Sergeant Wilson’s service number was in fact 13003363, not 12014092. Charles Reed Wilson was born on February 6, 1917, in Three Springs, Pennsylvania, to James and Naomi Wilson, went on active duty in the U.S. Army on September 17, 1940, and reenlisted in the Army Air Forces on October 29, 1945. He switched to the U.S. Air Force after it became independent and continued to serve until July 1, 1964, eventually becoming a chief warrant officer. He died of cancer on August 13, 1970.

Exactly how that 1942 morning report came to list the wrong Charles R. Wilson’s service number is unknown.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for obtaining Wilson’s court martial file, to John Mier for his final pay voucher, and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

Census Record for Charles Wilson. April 4, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9MR-M33

Census Record for Charles Wilson. April 14, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR4B-ZF1

Certificate of Birth for Charles Raymond Wilson. Undated, c. July 16, 1921. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D14Q-1ZL

Certificate of Death for Charles Raymond Wilson. Undated, c. April 25, 1943. Record Group 1500-008-092, Death Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6L6Q-MCD

Enlistment Record for Charles R. Wilson. March 17, 1941. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=12014092&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=484703

“Final Statement of Charles R. Wilson, 12014092, Pvt. Unasgd 715th Training Group.” May 1943. Individual Pay Vouchers, c. 1926–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of John Mier.

“Five Inquests Held By Coroner.” Wilmington Morning News, May 6, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154025021/

General Court Martial Case File for Charles R. Wilson. Army General Courts-Martial Records of Trial, 1939–1976. Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), 1792–2010. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

Morning Reports for 58th Pursuit Squadron. March 1941 – August 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0182/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0182-21.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0182/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0182-22.pdf

Morning Reports for 306th Materiel Squadron. August 1941 – July 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0230/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0230-07.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0230/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0230-08.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0230/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0230-09.pdf

Morning Reports for Air Force Detachment, Force Cedar. March 1942 – February 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-3120/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-3120-02.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-3120/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-3120-03.pdf

Morning Reports for Prisoners, Fort DuPont, Delaware. November 1942 – March 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2863/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2863-07.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2863/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2863-08.pdf

“Soldier Dies As Auto Hurtles Into Creek.” Wilmington Morning News, April 26, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154025434/

Wilson, Beatrice. Individual Military Service Record for Charles R. Wilson. Undated, c. 1949. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/21431/rec/8

Last updated on February 4, 2026

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.