| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Worker at Pennsylvania Railroad shops |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32359737 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | 18th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 34th Bombardment Group (Heavy) |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 612 (airplane armorer-gunner) | European air campaign (one mission) |

Early Life & Family

Dougal MacLean Beatson was born at the Delaware Hospital in Wilmington, Delaware, on the morning of September 12, 1919. He was the second child of John MacLean Beatson (a painter for the Pennsylvania Railroad, c. 1882–1932) and Florence Beatson (née Florence E. Kilpatrick, 1898–1979). All the men in the family shared the same middle name, though there are some spelling variations in different records. When he was born, Beatson’s family was living at 2001 Market Street in Wilmington. Beatson had an older brother, John M. Beatson (1918–1997), two younger brothers, Duncan M. Beatson (1921–2015) and Malcolm M. Beatson (1922–1997), and a younger sister, Janet A. Beatson (1929–2006?). He was Protestant.

The Beatson family was still living at 2001 Market Street at the time of the 1920 census, though curiously Beatson’s first name was recorded as William. The family had moved to 1810 Washington Street in Wilmington by the time Duncan was born on April 4, 1921. The family was recorded at the same address in the 1930 census. When Beatson was 12, his father died of pneumonia at their home on March 19, 1932. Census records indicate that the rest of the family subsequently moved to 2309 Pine Street prior to April 1, 1935. Beatson was still living there as of April 1, 1940, and it appears that it was his residence until he entered the service.

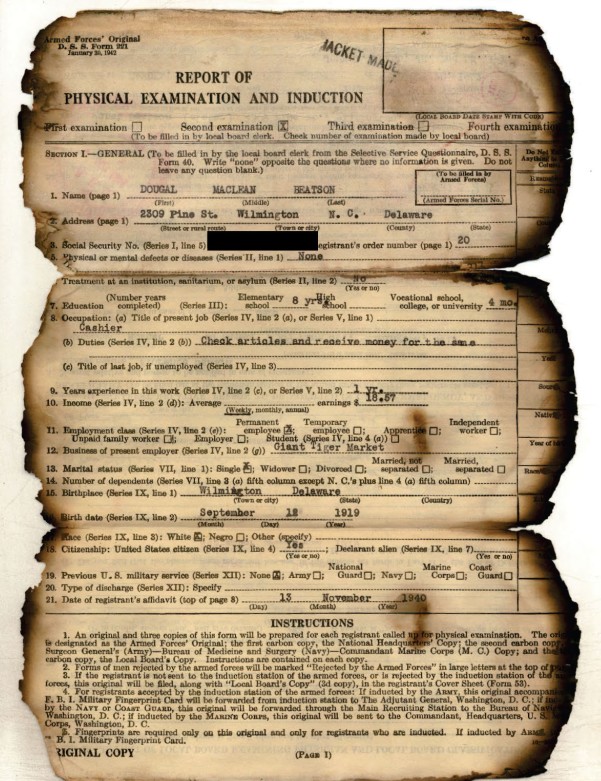

When Beatson registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, he was working at Giant Tiger Market at 2nd and French Streets in Wilmington. The registrar described him as standing five feet, 3½ inches tall and weighing 123 lbs., with brown hair and blue eyes. According to data later copied onto his induction paperwork from a Selective Service affidavit, dated November 13, 1940, Beatson had one year of experience working as a cashier, earning $18.57 per week (about $346 in 2025 dollars). Journal-Every Evening reported that “Beatson was employed at the Pennsylvania Railroad Shops” in Wilmington prior to entering the service.

According to his enlistment data card, Beatson had completed one year of high school. On the other hand, his induction paperwork stated that Beatson had completed eight years of grammar school and four months of “Vocational school, college, or university” (most likely the former).

Local Board No. 2, Wilmington, examined Beatson and classified him as eligible for military service on August 7, 1942. He was drafted soon afterward. His brothers, John and Duncan, also both served in the military during World War II.

Military Career & Marriage

Beatson was inducted into the U.S. Army in Camden, New Jersey, on August 20, 1942. As was customary for selectees, he was briefly transferred to the Enlisted Reserve Corps on inactive duty. Private Beatson went on active duty on September 3, 1942, at Fort Dix, New Jersey, where he was briefly attached to Company “C,” 1229th Reception Center. He was transferred on September 5, 1942, along with a group of men that included LeMoyne Pierson (1905–1944), another Delawarean destined to die while serving with the Army Air Forces (A.A.F.).

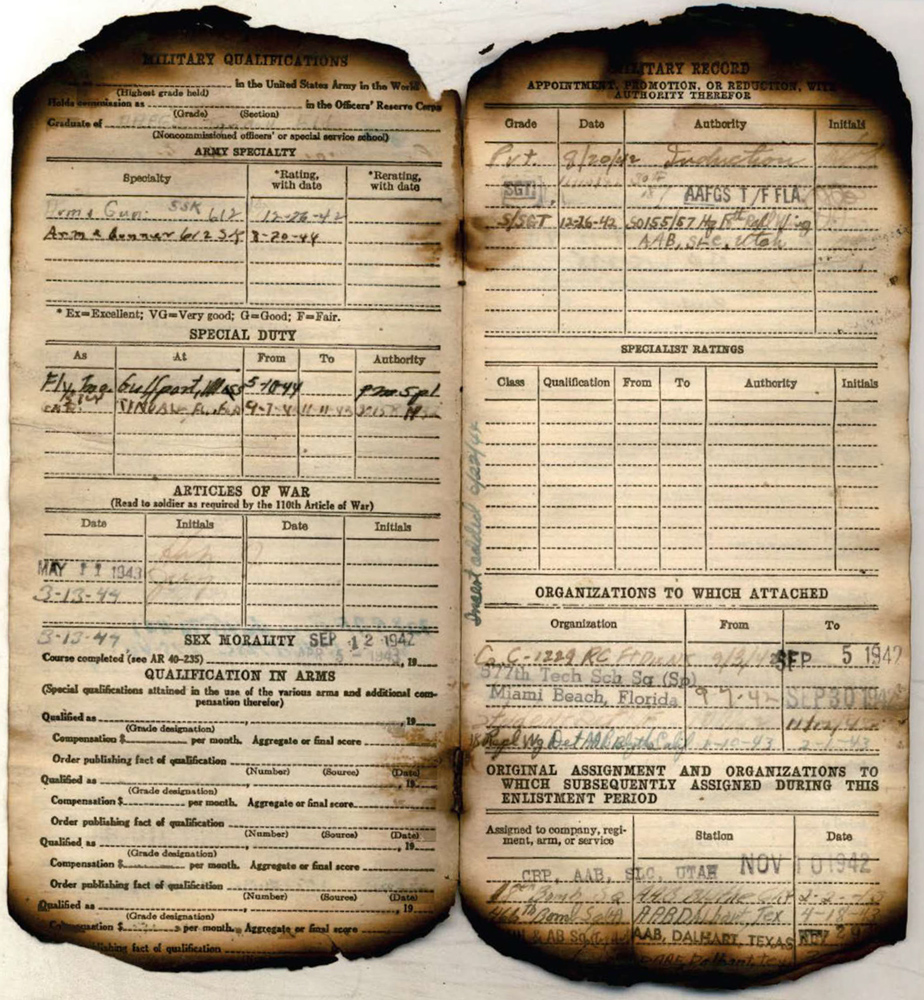

On September 7, 1942, Private Beatson was attached unassigned for basic training with the 577th Technical School Squadron (Special) at the Army Air Forces Technical Training Center, Miami Beach, Florida. He was detached from that squadron on September 30, 1942. The following month, after volunteering to become air crew, he attended flexible gunnery training at Tyndall Field, Florida. He remained with that unit until the following month. An entry in his personnel file recording Beatson’s promotion to sergeant is faded, but looks like it was dated around November 15, 1942, on the authority of Special Orders No. 18, Army Air Forces Flexible Gunnery School, Tyndall Field, Florida.

According to his personnel file, on November 10, 1942, Beatson joined the Classification Routing Pool, Army Air Base, Salt Lake City, Utah. This date might be slightly inaccurate, since the same page states he was at gunnery school until November 12, 1942.

Beatson was promoted to staff sergeant on December 26, 1942. That same day, he was rated with the military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code of 612, airplane armorer-gunner. On January 10, 1943, Staff Sergeant Beatson was attached unassigned to the 18th Replacement Wing Detachment, Army Air Base, Blythe, California. He remained with that unit until February 1, 1943. The following day, he joined the 18th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), a replacement training unit also located at Blythe and equipped with the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress.

On April 18, 1943, Beatson joined the 466th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 333rd Bombardment Group, an operational training unit at Dalhart Army Air Field, Texas. Beatson got his first furlough during June 5–17, 1943, returning to duty on June 18. On November 29, 1943, when his unit was disbanded, his name appeared on a list of “instructor personnel.” Indeed, his widow told the Public Archives Commission that Beatson was a gunnery instructor from June 1943 until August 1944.

Staff Sergeant Beatson transferred to the 338th Base Headquarters & Air Base Squadron (Training Unit) per Special Orders No. 265, Headquarters 333rd Combat Crew Training School, Army Air Base, Dalhart, Texas, dated November 29, 1943. He began a furlough on December 28, 1943, returning to duty on January 11, 1944.

During March 21–30, 1944, all personnel in the 338th Base Headquarters & Air Base Squadron (Training Unit) were transferred to Section “E,” 232nd Army Air Forces Base Unit (Combat Crew Training School) and the 338th was disbanded. This was part of a larger trend in which the A.A.F. reorganized its stateside training units, disbanding and consolidating training squadrons and groups into A.A.F. base units.

On April 29, 1944, a set of orders came down effective May 1, transferring a large group of men from the 232nd to Gulfport Army Air Field, Mississippi. There, on May 5, 1944, he joined Section “T,” 328th Army Air Forces Base Unit, a heavy bomber replacement training unit. The following month, Section “T” was redesignated as Squadron “T.”

Beatson went on furlough on June 28, 1944. A few days later, on July 2, 1944, he married Carmen Kimball (1923–1989) in Trinidad, Colorado. He returned to duty on July 13, 1944. Staff Sergeant Beatson was released from Squadron “T” and attached unassigned to Squadron “S,” 328th Army Air Forces Base Unit, on July 15, 1944.

At Gulfport, probably in July and by August 20, 1944, Beatson joined a crew led by 2nd Lieutenant Robert E. Dixon (1924–1944). A native of Lynn, Massachusetts, Dixon had been a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology before joining the military. He had been rated as a pilot on March 12, 1944, and completed transition training to fly the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress four-engine bomber.

On August 21, 1944, during a training mission to the air-to-air gunnery range, a gunner in the crew, Sergeant Edgar H. Brueggemann (1920–1996), suffered an eye injury when a .50 round exploded while he was stowing the gun before leaving the range. He was hospitalized and did not go overseas with the crew.

As of August 25, 1944, Staff Sergeant Beatson was qualified as an air crew member after completing all training. As of August 30, 1944, he was “favorably considered for Good Conduct Medal” and he had served long enough to receive it, but there is no indication that it was awarded prior to his death.

On August 31, 1944, Beatson and his crew were dispatched by rail to Hunter Field, Georgia, with orders to report at the Combat Crew Center, 3rd Air Force Staging Wing. That day, Beatson was attached unassigned to Squadron “S,” 302nd Army Air Forces Base Unit. Per Special Orders No. 247, Headquarters Third Air Force Staging Wing, dated September 3, 1944, Beatson and his crew were assigned B-17G serial number 43-38530 and ordered to proceed “immediately by air to Dow Field, Bangor, Me, […] for temp duty pending further dispatch to overseas destination.” They departed Hunter Field the following day, September 4, and had a short flight on September 5.

According to his personnel file, Beatson departed the United States for overseas duty from Grenier Field, New Hampshire, on September 6, 1944. Lieutenant Dixon’s flight records suggest that the crew ferried a new B-17G, serial number 43-38530, across the Atlantic Ocean. Curiously, those records do not indicate any flight on September 6, 1944, though they record flights on the 7th, 11th, 18th, and 19th. It is likely that their journey was extended by weather or mechanical issues.

Given the relatively short flight times and the fact that the overseas journey took nearly two weeks, it is likely that Beatson and the others were delayed by weather or mechanical issues and had intermediate stops in Canada, Greenland, and Iceland.

When Beatson went overseas, his wife was pregnant with a son that he would never have the chance to meet.

Service in the European Theater

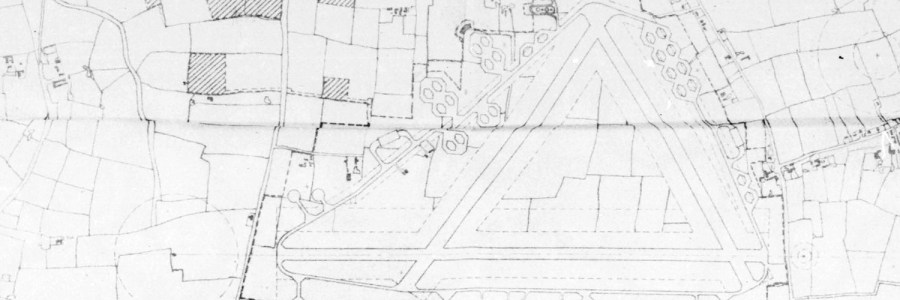

On September 19, 1944, Staff Sergeant Beatson and his crew arrived in the United Kingdom, landing at Royal Air Force Valley, Wales. Bomber crews did not get to keep the aircraft they crossed the ocean aboard, and 43-38530 ended up assigned to the 303rd Bombardment Group (Heavy). Beatson joined the Casual Pool, 70th Replacement Depot (Army Air Forces) and along with the other enlisted men in his crew was attached unassigned to Squadron “B,” 14th Replacement Control Depot (Aviation) at Stone, Staffordshire, to await assignment. A set orders came down on September 23, 1944, effective on or about the following day, dispatching Beatson’s crew to the 34th Bombardment Group (Heavy), U.S. Eighth Air Force, at Royal Air Force Mendlesham, Suffolk, England. The group had just finished converting from the Consolidated B-24 Liberator to the B-17, flying its first mission with the new aircraft on September 17, 1944.

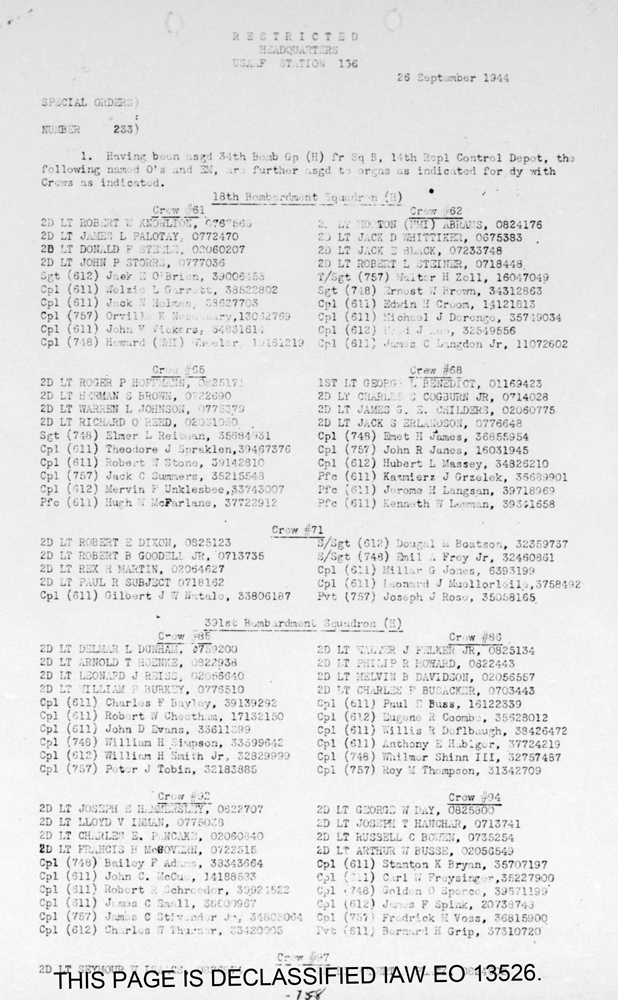

According to his personnel file, Beatson joined the 18th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 34th Bombardment Group (Heavy), on September 25, 1944, though Special Orders No. 233, Headquarters U.S.A.A.F. Station 156, gave the date of his crew’s assignment to the squadron as the following day.

Beatson’s pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Dixon, flew an orientation mission as a copilot on September 27, 1944, and training or administrative flights on October 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13. It is likely that Beatson flew on at least some of these flights. According to a group history, there were regular air raid alerts and on October 10, “two Buzz Bombs [V-1 flying bombs] passed directly over the field at 300 feet.”

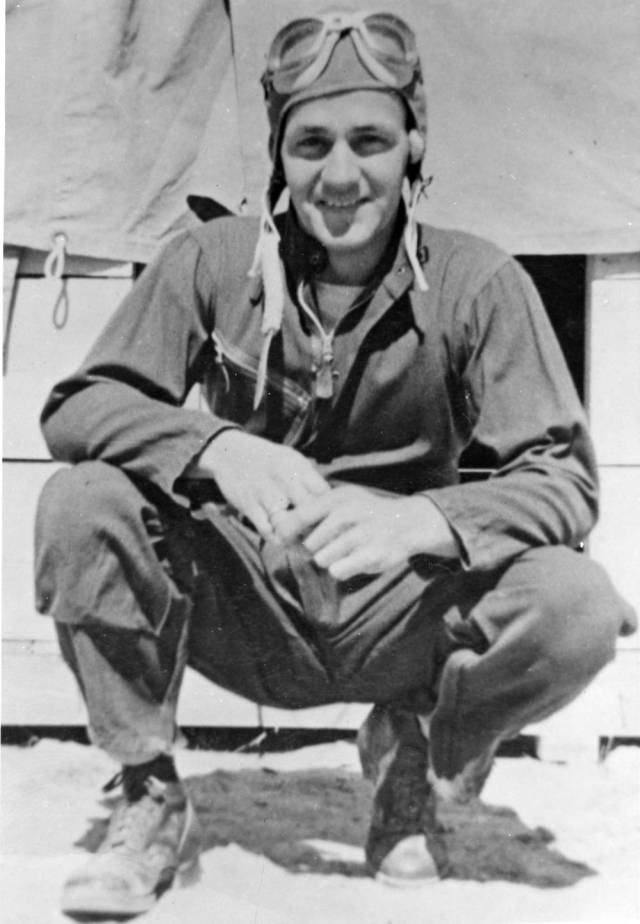

Both Dixon and his copilot, Robert Bruce Goodell, Jr. (1918–2008), were still relatively inexperienced pilots. According to his individual flight records, by October 15, 1944, 2nd Lieutenant Dixon had 571 hours and 10 minutes of flight time under his belt, including 149 hours and 25 minutes as first pilot since earning his wings. A set of figures included in an accident report stated that Dixon had 223 hours and 25 minutes as first pilot (including his time as an aviation cadet), with 123 hours and 55 minutes flying the B-17.

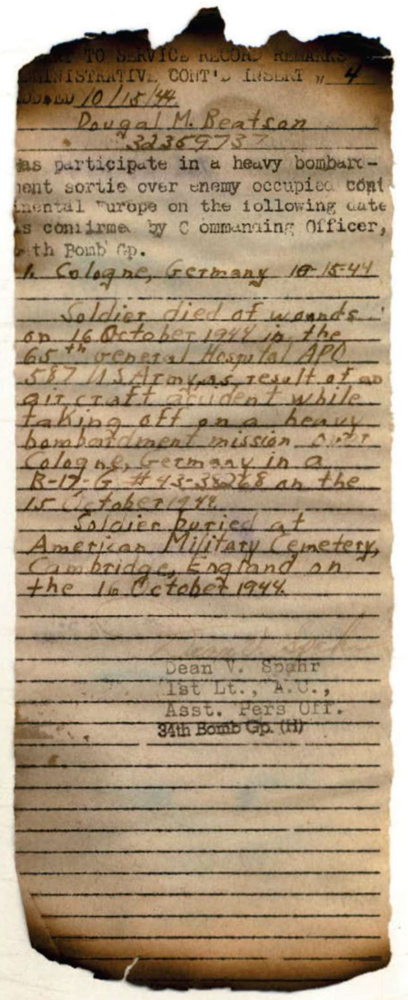

On October 15, 1944, Staff Sergeant Beatson boarded a B-17G, serial number 43-38268. He and his crew probably did not get adequate rest the night before, which had repeated air raid warnings. It was a hazy morning, with visibility about two miles. He was assigned the duty of waist gunner. The mission, almost certainly his first combat mission, was a raid on Cologne, Germany.

Beatson’s crew was mostly familiar faces, but a few men were different. Three of the men he had gone overseas with were not on the flight. The Army Air Forces were training heavy bomber crews with 10 men. However, with the threat of enemy fighters diminished, by that time the 34th Bomb Group was flying missions with nine-man crews, omitting one of the waist gunners. For unknown reasons, the navigator aboard, 2nd Lieutenant Donald Franklin Steele (1922–2008), was a substitute, as was the tail gunner, Staff Sergeant Richard F. Wolfe (1923–1944).

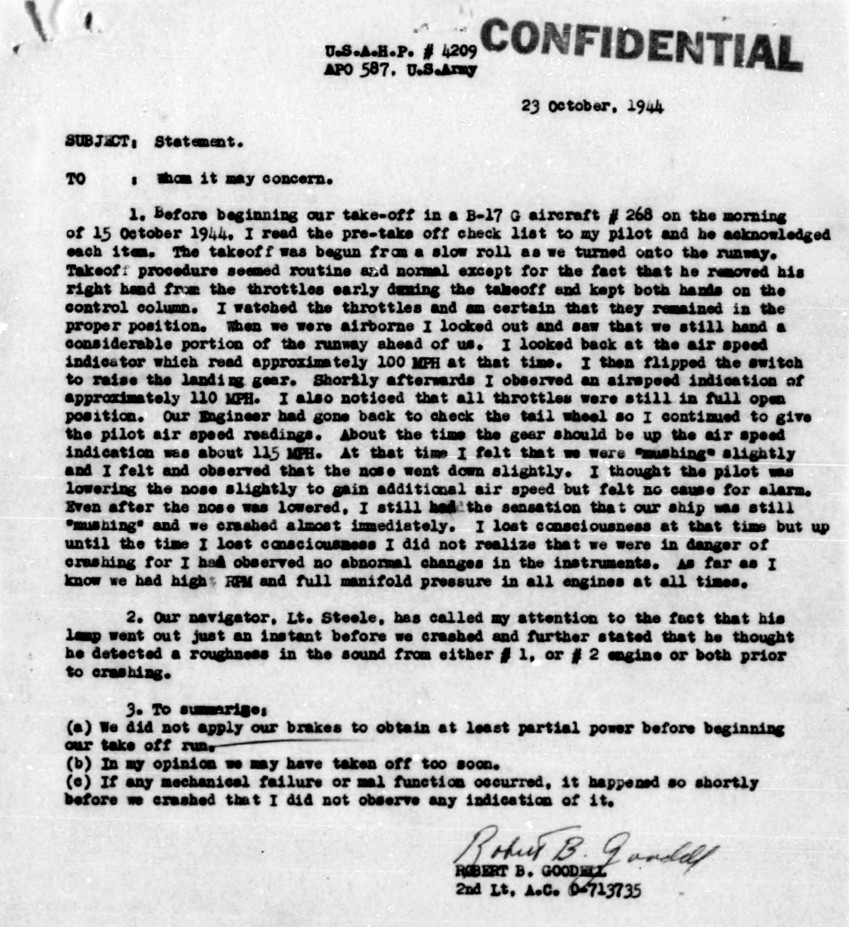

When it was time for takeoff, Lieutenant Dixon turned the B-17 onto Runway 28. It took time for aircraft engines to spool up to full power. As a board of investigating officers later noted, the best practice was for B-17 pilots to stop at the end of the runway, apply the brakes, and advance the throttle prior to releasing the brakes, but Dixon did not do that. His copilot, Lieutenant Goodell, later recalled: “The takeoff was begun from a slow roll as we turned onto the runway.”

Attempting to take off before the B-17 reached a speed of at least 110 miles per hour also went against best practices. Goodell later wrote that Dixon rotated the aircraft about two-thirds of the way down the runway at an air speed of 100 m.p.h., adding: “In my opinion we may have taken off too soon.” It is unclear if that was his impression at the time or merely in retrospect. Goodell raised the landing gear, but recalled that even though “all throttles were still in full open position” the plane failed to gain much speed or altitude.

The incident occurred decades before the advent of cockpit resource management (C.R.M.), which emphasizes the importance of communication between all members of flight crews. Among other things, C.R.M. seeks to avoid a common situation where copilots or other members of flight crews recognize a dangerous situation but fail to adequately call attention to it out of deference to the lead pilot. Whether due to this phenomenon or his own experience, Goodell’s passivity was evident. By his own account, Goodell took no actions during takeoff other than to call out the plane’s air speed. He wrote:

About the time the gear should be up the air speed indication was about 115 MPH. At that time I felt we were “mushing” slightly and I felt and observed that the nose went down slightly. I thought the pilot was lowering the nose slightly to gain additional air speed but felt no cause for alarm.

Goodell recognized that the B-17 was not gaining speed as it should after takeoff and felt that the plane was “mushing,” meaning it was failing to climb and losing altitude despite having its nose up and the throttle open. The B-17 was now seconds from crashing but neither pilot recognized it. One contributing factor may have been condensation on the windscreen which obscured their view. Goodell continued:

Even after the nose was lowered, I still had the sensation that our ship was still “mushing” and we crashed almost immediately. I lost consciousness at that time but up until the time I lost consciousness I did not realize we were in danger of crashing for I had observed no abnormal changes in the instruments. As far as I know we had high RPM and full manifold pressure in all engines at all times.

At 0519 hours, one minute after takeoff, the B-17 crashed into a farmer’s field about 1,500 feet from the end of the runway. Investigators reported: “Shortly after take-off the aircraft was observed to make a rather flat turn to the left and fly into the ground.”

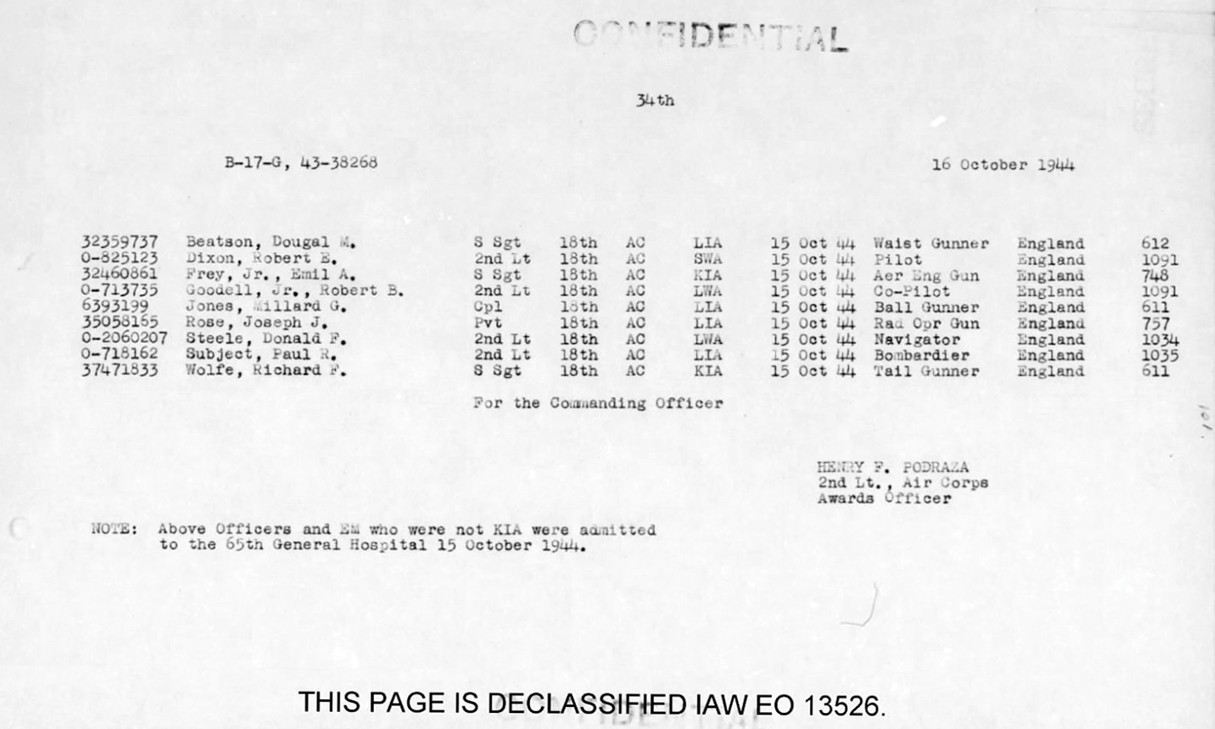

The B-17 caught fire and some of the bombs aboard detonated. Two men were killed outright: Staff Sergeant Emil A. Frey, Jr. (1914–1944), the flight engineer, and the tail gunner, Staff Sergeant Wolfe. Staff Sergeant Beatson suffered burns to his face, ears, neck, hands, and most seriously of all, to his airway. Rescue equipment and ambulances rushed to the crash scene and transported the remaining seven members of the crew to U.S. Hospital Plant 4209 (65th General Hospital) in Redgrave, Suffolk.

The accident report noted that “Four (4) bombs (250 lb.) unaccounted for” after the crash, but does not make clear if that is because they were lost or because they detonated.

Two members of the crew, Sergeant Millard Gordon Jones (1920–2008) and Private Joseph J. Rose (who was promoted to sergeant the day after the crash, 1911–1994), were later awarded the Soldier’s Medal for their actions in helping to rescue their injured comrades after the crash. In 1945, The Asheville Times reported about Jones, who suffered permanent injuries in the incident:

“I don’t know what happened—we went up to about 100 feet and the B-17 Just wouldn’t take any more altitude. It was my first mission. We crashed and the incendiary bombs exploded—next the five-hundred pounders caught on file. The pilot was killed,” Sgt. Jones said.

Sgt. Jones was blown 200 feet from the plane, his clothes smoking and on fire. He returned to the burning plane, rescued the co-pilot and had started back when the bombs exploded. He was forced to lay down in an attempt to smother the flames while he took his “Mae West” [lifejacket] off. Unable to get the heated suit-jacket off, he rolled over to extinguish the flames. He suffered severe burns.

Despite treatment, edema (swelling) in Beatson’s larynx resulted in his death by asphyxiation the day after the crash, October 16, 1944. Lieutenant Dixon died from his injuries the same day. Beatson was initially buried at the U.S. military cemetery in Cambridge, England, on the afternoon of October 19, 1944. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

Investigators suggested in their report that Dixon “was trying to fly contact under instrument conditions or became confused when changing from contact to instrument procedure. If this is the case the pilot is charged with 100% pilot error.”

Although that was the most likely cause of the crash, investigators were unable to rule out the possibility of mechanical failure. The navigator, Lieutenant Steele, reported hearing an unusual sound from one of the two engines on the left side of the aircraft shortly before the crash, possibly indicating the possibility of engine failure. If that happened, the investigators concluded, mechanical failure was 75% to blame. However, Lieutenant Goodell noted: “If any mechanical failure or mal function occurred, it happened so shortly before we crashed that I did not observe any indication of it.”

The following year, Staff Sergeant Beatson’s widow gave birth to their son. After the war, in March 1947, she requested that his body be repatriated to the United States. The following year, his casket returned from Cardiff, Wales, to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the Lawrence Victory. On July 20, 1948, he was buried at the Soldiers’ Home National Cemetery in Washington, D.C., now known as the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery.

Staff Sergeant Beatson’s widow remarried, to his older brother, John, in Wilmington on September 6, 1947. The couple raised Sergeant Beatson’s son and had one son of their own.

Beatson’s name is honored on the Wall of Remembrance at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware, and on the Pennsylvania Railroad World War II Memorial at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Crew of B-17G 43-38268 on October 15, 1944

The following list is based on 34th Bomb Group unit records with grade, name, service number, position, and status (lightly injured in action, seriously injured in action, killed in action, or died of injuries).

2nd Lieutenant Robert E. Dixon, O-825123 (pilot) – D.O.I.

2nd Lieutenant Robert B. Goodell, Jr., O-713735 (copilot) – L.I.A.

2nd Lieutenant Paul R. Subject, O-718162 (bombardier) – L.I.A.

2nd Lieutenant Donald F. Steele, O-2060207 (navigator) – L.I.A.

Staff Sergeant Emil A. Frey, Jr., 32460861 (flight engineer) – K.I.A.

Private Joseph J. Rose, 35058165 (radio operator) – S.I.A.

Staff Sergeant Dougal M. Beatson, 32359737 (waist gunner) – D.O.I.

Sergeant Millard G. Jones, 6393199 (ball turret gunner) – S.I.A.

Staff Sergeant Richard F. Wolfe, 37471833 (tail gunner) – K.I.A.

Notes

Purple Heart

Generally, the Purple Heart is awarded for wounds or death sustained in battle due to enemy action. Some exceptions existed, such as wounds from friendly fire directed at the enemy. Although the crash was not the result of enemy action, during World War II the military commonly awarded the Purple Heart to air crew hurt or killed during combat missions, regardless of the cause. As a result, Staff Sergeant Beatson was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Matt LeMasters for providing Lieutenant Dixon’s flight records, to Lieutenant Colonel Scott Taylor for providing a pilot’s insight into the circumstances of the crash, and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“34th Bomb. Group History October 1944.” Reel B0114. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“43-38268.” Publication date unknown. Updated on September 27, 2014. American Air Museum in Britain website. https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/aircraft/43-38268

“Army and Navy Official Reports.” The Kansas City Times, November 8, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/179792632/

“B-17 43-38530.” Publication date unknown. Updated on September 11, 2017. B-17 Bomber Flying Fortress – The Queen Of The Skies website. https://b17flyingfortress.de/en/b17/43-38530/

Beatson, Carmen. Individual Military Service Record for Dougal MacLean Beatson. September 21, 1944. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17638/rec/5

“Carmen K. Beatson.” The News Journal, August 24, 1989. https://www.newspapers.com/article/188781574/

Census Record for Dougal Beatson. April 14, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRHM-J93

Census Record for Dougal Beatson. April 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9MR-M3S2

Census Record for William [sic] Beatson. January 6, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR67-BJF

Certificate of Birth for Dougal McLone [sic] Beatson. Undated, c. September 1919. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DT89-Z5

Certificate of Birth for Duncan MacLean Beatson. 1921. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D147-SHG

Certificate of Death for John MacLean Beatson. March 19, 1932. Record Group 1500-008-092, Death Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DYNQ-6TM

Certificate of Marriage for John M. Beatson and Carmen Kimball Beatson. September 6, 1947. Record Group 1500-008-093, Marriage Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-X9K9-BR8

“Col. Donald Steele USAF-Ret.” The Charlotte Observer, March 29, 2008. https://www.newspapers.com/article/188693660/

Crook, Lonnie H. “Commentaries for the Month of Sept Group Bombardier.” Undated, c. October 1944. Reel B0114. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Delawarean Dies of Wounds Received in Air War Abroad.” Journal-Every Evening, December 7, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/179954430/

Draft Registration Card for Dougal MacLean Beatson. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-XSVD-G

“Edgar Herman Brueggemann.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/242575090/edgar-herman-brueggemann

Ferrell, Gary L. “34th Bomb Group Combat Mission Diary: OCTOBER 1944 Missions #71-#85.” Valor to Victory: 34th Bomb Group website. https://34thbg.org/ValorToVictory/1944-10.htm

Gay, Robert S. “Group History for Month of September, 1944.” Undated, c. October 1944. Reel B0114. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Hospital Admission Card for 32359737. October 1944. U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/704771020/beatson-dougal-m-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Dougal M. Beatson. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Individual Flight Record for Robert E. Dixon. January 1944 – October 1944. Individual Flight Records, 1911–1958. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Matt LeMasters.

Interment Control Form for Dougal M. Beatson. 1948. Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_1521003240_0484-01095

“Jones Awarded Soldiers Medal At England Base.” The Asheville Citizen, April 25, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/188758853/

“Joseph J. Rose.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/199843349/joseph-j.-rose

“Joseph Rose, 82, decorated for saving lives during WWII.” The Plain Dealer, March 1, 1994. https://www.newspapers.com/article/188760667/

LeBailly, Eugene B., Fandel, William H., and Hershenow, William J., Jr. “Report of Aircraft Accident 45-10-15-530.” October 24, 1944. Reel 46434. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Millard Gordon Jones.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/25052346/millard-gordon-jones

Morning Reports for 18th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy). September 1944 – October 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-09/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0606/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0606-18.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0706/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0706-27.pdf

Morning Reports for 338th Base Headquarters & Air Base Squadron (Training Unit). March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0277/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0277-18.pdf

Morning Reports for 338th Base Headquarters & Air Base Squadron (Training Unit). November 1943 – January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378-02.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378-03.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0094/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0094-04.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0128/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0128-13.pdf

Morning Reports for 469th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy). November 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378-09.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0378-10.pdf

Morning Reports for 577th Technical School Squadron (Special). September 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0320/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0320-10.pdf

Morning Reports for 4209 U.S. Army Hospital Plant. October 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0586/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0586-04.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 1229th Reception Center. September 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2841/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2841-02.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment of Patients, Army Air Forces Station Hospital, Gulfport Army Air Field, Mississippi. August 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-08/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0005/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0005-27.pdf

Morning Reports for Section “E,” 232nd Army Air Forces Base Unit. May 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-05/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0278/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0278-12.pdf

Morning Reports for Section “T,” 328th Army Air Forces Base Unit. May 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-05/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0433/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0433-05.pdf

Morning Reports for Squadron “B,” 14th Replacement Control Depot (Aviation). September 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-09/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0505/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0505-19.pdf

Official Military Personnel File for Dougal M. Beatson. Official Military Personnel Files, 1912–1998. Record Group 319, Records of the Army Staff. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Our Men in Service.” Daily Evening Item, May 2, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/188746233/

Podraza, Henry F. “B-17-G, 43-38268.” October 16, 1944. Reel B0114. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Robert Bruce Goodell Jr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/65800328/robert-bruce-goodell

Soldier’s Medal Decoration Card for Millard G. Jones. Air Force Award Cards. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/148250465?objectPage=684#object-thumb–684

“SSGT Emil Albert Frey Jr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56289837/emil-albert-frey

“Two Brothers Reunited Here After 6 Years.” The Asheville Times, April 17, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/188759494/

“Unseen Son to Attend His Father’s Funeral.” Journal-Every Evening, July 15, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/article/139480612/

Wieser, Vincent M. “Report of Aircraft Accident 45-8-21-46.” August 30, 1944. Reel 46413. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Last updated on January 29, 2026

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.