| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Maryland, Delaware | Machinist for the Haveg Corporation |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 42085071 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “C,” 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 746 (automatic rifleman) | Rhineland campaign, Ardennes–Alsace campaign |

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my previous article, Private Herbert Rubenstein (1923–1944), another member of the 423rd Infantry Regiment involved in the Battle of the Bulge.

Early Life & Family

Paul Howard Rigdon was born on January 21, 1923, in Street, Harford County, Maryland. He was the son of Harold Rigdon (a farmer, 1893–1961) and Velma Rigdon (née Velma Alfreida Gordon, 1904–1962). He had a younger sister, Dora May Rigdon (later Hastings, 1924–2000), who went by her middle name.

The Rigdon family was recorded in census records in April 1930 living in unincorporated Harford County, Maryland. At the time of the next census in April 1940, they were living on a farm along Mill Green Road in Dublin, Mayland, an unincorporate area of Harford County just west of the Conowingo Dam and the Susquehanna River. Rigdon’s occupation was listed as farmhand.

The Aegis, a weekly newspaper in Bel Air, Maryland, reported in 1945 that

Rigdon was engaged in farming with his father near Mill Green until 1941, when the family moved to Delaware. After settling there he was employed as a machinist at a Marshallton, Del., plant where his father and sister are still working.

When Rigdon registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, he was living at 202 Ohio Avenue in Elsmere, Delaware, and working for the Haveg Corporation in nearby Marshallton. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, 11 inches tall and weighing 135 lbs., with brown hair and eyes.

According to the 1940 census, Rigdon completed only the 7th grade before dropping out of school.

His enlistment data card described him as a machinist with a grammar school education. He was Protestant.

Military Career

After he was drafted by Local Board No. 1, New Castle County, Rigdon was inducted into the U.S. Army at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on February 28, 1944. He went on active duty that same day and was attached unassigned to Company “D,” 1229th Reception Center. On March 10, 1944, he was dispatched to the Infantry Replacement Training Center, Camp Wolters, Texas. He arrived there by midday on March 13, 1944, and was attached unassigned to the 53rd Infantry Training Battalion. Effective the following morning, he was further attached to that battalion’s Company “C” for basic training.

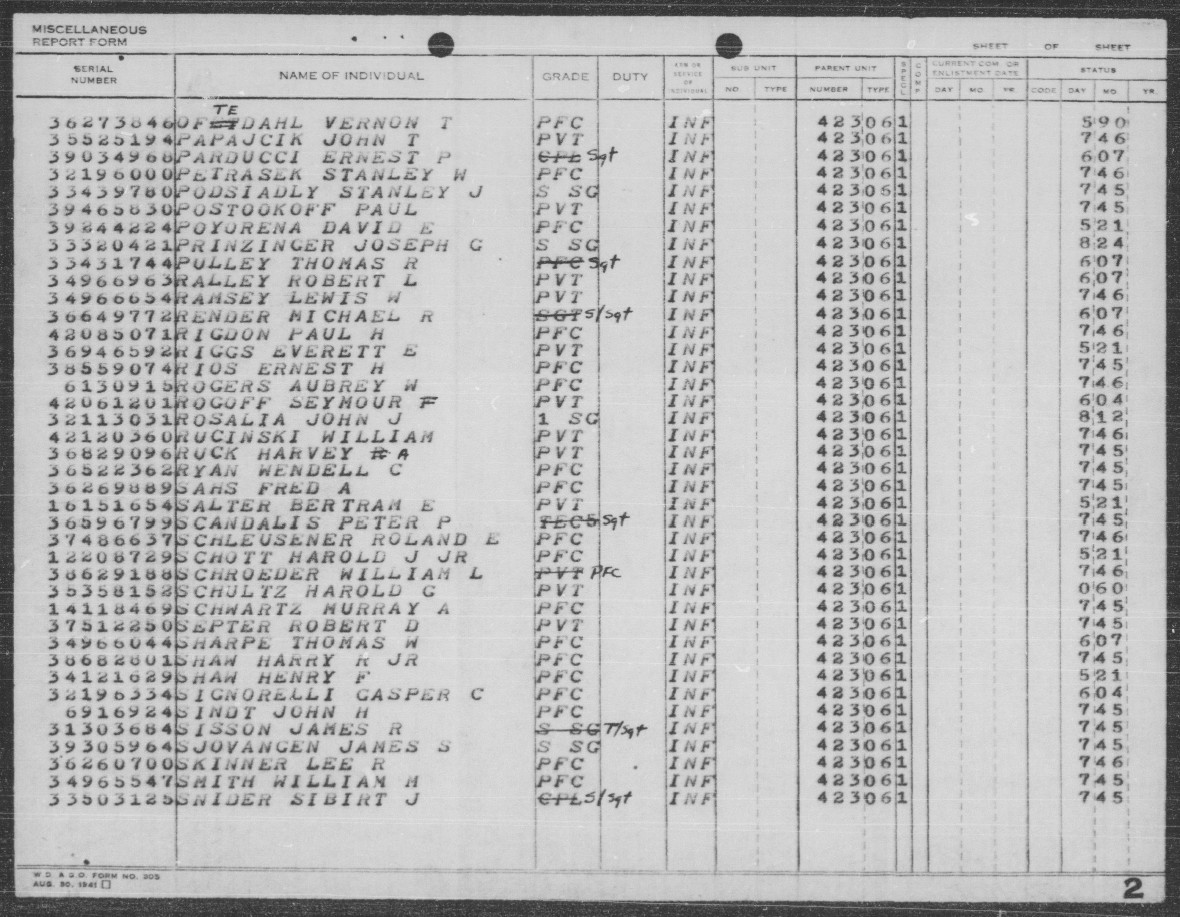

Upon completing basic training, Private Rigdon qualified in the military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) of 610, antitank gun crewman. On July 14, 1944, Rigdon was transferred to Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot No. 1, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland. On August 29, 1944, a set of orders came down transferring Rigdon to the 106th Infantry Division effective the following day.

On August 31, 1944, at Camp Atterbury, Indiana, Private Rigdon joined Company “C,” 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division. The division was commanded by Major General Alan Walter Jones (1894–1969).

Infantry units took the highest casualties in the Army Ground Forces. In early 1944, with combat in Italy and the Pacific already testing the Army’s capability to induct and train enough new riflemen, the 106th Infantry Division was repeatedly stripped and thousands of its men sent overseas as replacements. In turn, the slots they vacated were backfilled with other men, including those fresh from basic training and from the largely discontinued Army Specialized Training Program.

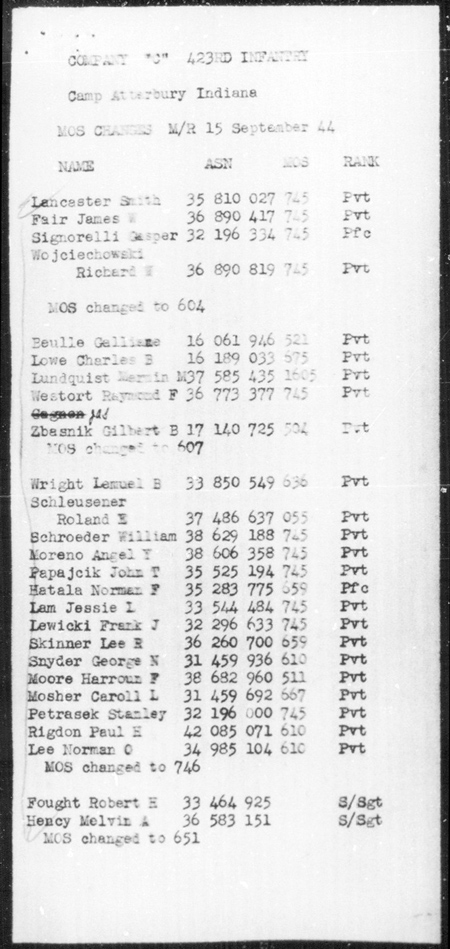

In a classic case of military necessity (or irrationality), the Army had trained Rigdon as an antitank gun crewmember and then transferred him to a rifle company that lacked antitank guns. A rifle company’s only defense against enemy armor was the rocket launcher universally known as the bazooka. On September 15, 1944, despite his lean build, Private Rigdon’s M.O.S. code changed to 746, automatic rifleman or assistant automatic rifleman. Similarly, The Aegis reported that he “went overseas in October as a Browning automatic rifleman.”

A rifle squad’s automatic rifleman was armed with the M1918 Browing Automatic Rifle. Although a popular weapon, it was heavy, weighing over 20 lbs. loaded. With its 20-round box magazine, it could provide only a fraction of the firepower of the belt-fed MG 34 and MG 42 machine guns that provided a base of fire for German rifle squads. Assistant automatic riflemen were, like the rest of the American rifle squad, armed with the M1 Garand semiautomatic rifle, but carried extra ammunition for the automatic rifle. The assistant could take over if the automatic rifleman became a casualty, which was often, since fog of war notwithstanding the enemy preferred to target those men wielding the most dangerous weapons against them. Another ammunition bearer rounded out the three-man automatic rifle team. Late in the war, some squads obtained a second automatic rifle in excess of the table of organization and equipment.

On the morning of October 8, 1944, Private Rigdon and his company boarded a train and headed east, arriving the following day at Camp Myles Standish, Massachusetts. On October 16, 1944, the 423rd Infantry moved to the New York Port of Embarkation, shipping out for the United Kingdom the following morning aboard the British ocean liner turned troop transport Queen Elizabeth. Steaming fast and unescorted, the ship pulled into the Firth of Clyde on October 22, 1944. With some 12,983 troops aboard, it was not until the afternoon of October 24, 1944, that Company “C” disembarked at Greenock, Scotland, and boarded a train to head south to England. At 0600 the following morning, Company “C” arrived at Andoversford, Glocestershire, England. Beginning on November 20, 1944, the company’s morning reports recorded its station as Sandywell Park, an estate about a mile northwest of Andoversford, but did not mention any move, suggesting that the morning report simply became more specific with its location that day.

Private Rigdon went on furlough November 20–23, 1944. He was promoted to private 1st class on December 1, 1944. At 0100 hours that same day, he and his company departed Sandywell Park. They boarded a train to Southampton, arriving at 0630. Three hours later, they boarded a vessel.

At 0200 hours the following morning, December 2, 1944, Company “C” shipped out for France. Upon arriving in La Havre at 1700 that same day, they began a long journey to the front lines by motor convoy.

Combat in the Ardennes

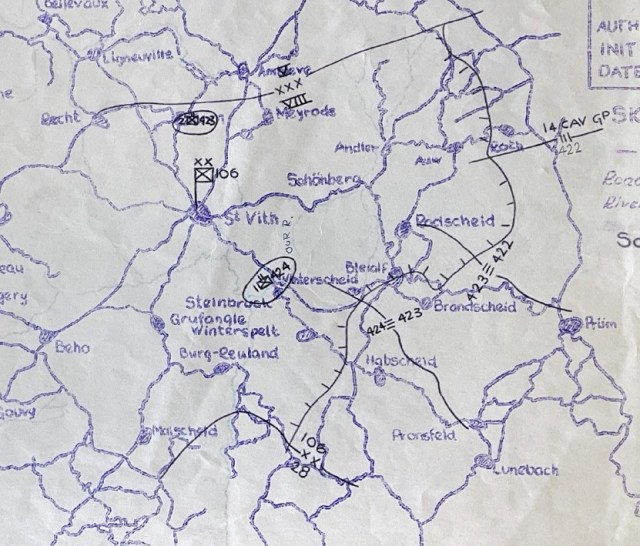

On December 9, 1944, the 423rd Infantry arrived at Saint-Vith, Belgium, where General Jones set up his command post. On December 11, 1944, the 106th Infantry Division took over defensive positions in the forested area known as the Schnee Eifel facing the German Westwall (known by the Allies as the Siegfried Line), relieving the 2nd Infantry Division. The sector was quiet while American forces concentrated on taking the Roer dams and driving into the Saarland. The 422nd Infantry was the northernmost regiment on the division’s left, most of Rigdon’s 423rd Infantry was in the center, and the 424th Infantry was further south on the division’s right. The Americans sent out patrols and worked to foil nighttime patrols by the enemy.

Captain Alan Walter Jones, Jr. (1921–2014), who remarkably enough served in his own father’s division as a battalion operations officer during the upcoming battle, later recalled that the 423rd Infantry Regiment was responsible for covering a six-mile front with just two battalions and its regimental reserve consisted of only of “Elements of Service Company and Regimental Headquarters Company” rather than the customary battalion. He recalled: “In spite of the extreme discomfort of the cold, damp weather and inadequate winter clothing and the obviously extended and exposed position, morale was high. This was a quiet sector where men could learn rapidly but safely.”

Even with all three of its infantry regiments placed in the line, the division was spread dangerously thin, as were the units on its flanks. Normal doctrine was for a division to have two regiments in the line and one in reserve, but in this case the 106th Infantry Division’s most substantial reserve consisted of 2nd Battalion, 423rd Infantry. The lack of resources was partially due to the Allied broad front strategy exacerbated by logistical issues, such as long supply lines from French ports and delays in opening the port at Antwerp, Belgium.

Several other factors led to a disaster in the making. Allied intelligence largely failed to detect a German buildup in the Ardennes. Most intelligence officers—and for that matter, most Allied commanders—could simply not conceive of the possibility that the Germans would squander so much of their remaining strength with a counterattack that had absolutely no chance of attaining any major strategic objectives unless the Allies experienced the sort of collapse as had been suffered by France in 1940. The 106th Infantry Division’s commanding officer, Major General Jones, lacked combat experience and did not respond decisively to rapidly developing events. Division communications were dependent on wired lines which were disrupted during the first day of the battle.

Historian Steven J. Zaloga wrote that 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments

were positioned in a vulnerable salient on the Schnee Eifel, a wooded ridgeline protruding off the Eifel plateau. […] The area forward of the two regiments was very suitable for defense since it consisted of rugged forest with no significant roads. But it was flanked on either side by two good roads, from Roth to Auw, and Sellerich to Bleialf.

Those roads converged behind them to the west, meaning that if the enemy broke through traveling those roads, both regiments would quickly face encirclement. The road passing through Bleialf, Germany, on the 423rd Infantry’s right, was garrisoned only by Antitank Company, 423rd Infantry.

For several days, the 423rd Infantry’s activities were limited to patrolling and fending off German patrols. Captain Jones wrote: “Wheeled and tracked vehicle movements were reported by patrols on the nights of 14 and 15 December; the comment received by Corps concerning these reports was that the sounds heard were undoubtedly from enemy loudspeaker systems.”

On the morning of December 16, 1944, the Germans launched a massive counteroffensive through the Ardennes that came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge. The opening artillery bombardment disrupted the 423rd Infantry’s communications and destroyed a stockpile of ammunition. The enemy hit Antitank Company, 423rd Infantry, at Bleialf. A scratch force from the 423rd’s Cannon Company and Service Company, supplemented by a small number of combat engineers, tank destroyers, and field artillery, launched a successful counterattack, driving the enemy back.

During the opening day of the battle, the enemy probed Private 1st Class Rigdon’s 1st Battalion, but launched no major attacks. Despite managing to hold its position while taking few casualties, the 106th Infantry Division’s situation was dire. The sole regimental reserve, 2nd Battalion of the 423rd Infantry, had initially been deployed to Schönberg, Belgium, a crossroads to the west of the main body of the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments, but was committed to prop up the sagging left flank of the 422nd Infantry.

That evening, the division’s commander, Major General Jones consulted his superior, VIII Corps commander Major General Troy H. Middleton (1889–1976). Their phone connection was poor, and a catastrophic misunderstanding took place. Middleton ordered Jones to withdraw the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments, but Jones thought he had been instructed to keep them in place.

Early in the morning on the second day of the battle, December 17, 1944, a renewed enemy attack broke through at Bleialf. This southern pincer linked up at Schönberg with another pincer that had broken through the thinly spread 14th Cavalry Group to the north. Had 2nd Battalion, 423rd Infantry been able to remain in Schönberg, it might have held open an escape route for the two beleaguered regiments, or at the very least delayed their encirclement. Of course, it is by no means certain that even a regiment of inexperienced soldiers, much less a battalion, could have held the crossroads against a concerted enemy attack, though the fortunes of war are so unpredictable as to make counterfactuals fraught with peril. For instance, at nearby Lanzerath, Belgium, a single equally inexperienced American platoon held off concerted attacks for nearly a day, delaying an entire German division.

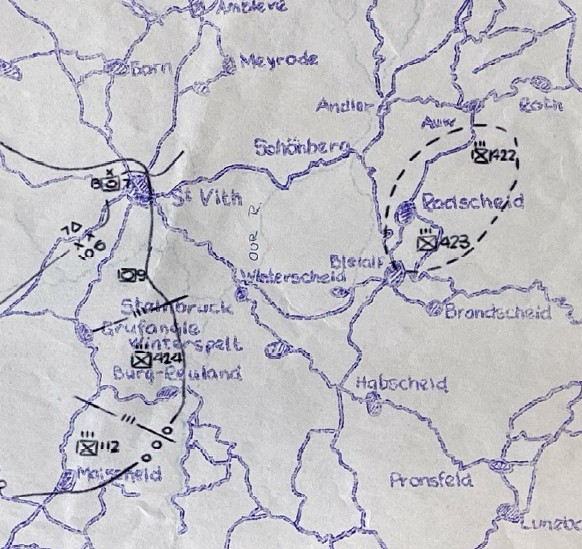

By that evening, the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments had been encircled, cutting them off from resupply. The enemy focused on continuing their drive westward rather than reducing the pocket and a breakout might have succeeded that day. However, the General Jones mistakenly believed that a relief force would arrive sooner than it did. He requested that supplies be delivered by air, but no such mission took place.

Zaloga wrote that on the morning of December 18, 1944, the 422 and 423rd Infantry Regiments received orders that they “should breakout towards St Vith, bypassing the heaviest German concentrations around Schönberg.” Later, these orders were changed to retake Schönberg and then withdraw to Saint-Vith. Leaving or destroying all non-essential equipment, supplies, and personal belongings, they began their march west before halting for the night southeast of Schönberg.

Captain Jones wrote that 1st Battalion was initially in the rear of the column, and Company “A,” left as a rearguard near Oberlascheid. He continued:

Learning that the enemy facing the 2d Battalion was rapidly being reinforced by enemy troops from the vicinity of BLEIALF, the regimental commander at about 1600 ordered the 1st Battalion to attack toward the southwest on the 2d Battalion’s left to assist that battalion and to cut off the flow of reinforcements from BLEIALF. Moving rapidly, the 1st Battalion, less one company as rear guard, deployed along HILL 546 just south of OBERLASCHEID. Supported by its heavy weapons company, the battalion launched its attack at dusk, around 1700, in what amounted to a night attack over unfamiliar territory, down into DUREN CREEK DRAW and up the lower slopes of the ridge extending south from RADSCHEID against a now heavily reinforced enemy. Against direct fire from German 88s, one of which was taken, and heavy automatic weapons and mortar fire the battalion drove some 1200 yards. Disorganized, nearly out of ammunition, and with about 70 casualties, the battalion pulled back to HILL 546 by 2200.

The following day, December 19, 1944, the 423rd Infantry made one last attempt to break through to Schönberg. Captain Jones wrote that contact had been lost with Company “A” and the battered Company “C,” “was pulled out of the battalion as it moved toward the line of departure to become the regimental rear guard.” 1st Battalion’s attack, which Jones said was limited to Company “B” and part of Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, was pummeled by enemy fire and the survivors forced to surrender. Largely as the result of its assault on December 18, Company “C” suffered the highest number of fatalities of any company in the regiment, with 17 men killed in action. Another three died as prisoners of war.

Rigdon was most likely killed in action during the fighting on December 18, 1944, though it is possible he died the following day, December 19, 1944. According to his burial report, Rigdon suffered a fatal shell fragment wound to the head.

Their ammunition exhausted, virtually all the men in the 423rd Infantry Regiment were forced to surrender on the afternoon of December 19, 1944. Together with the loss of the 422nd Infantry, it was the largest surrender of American forces in the European Theater during the entire war. However, their brief stand had delayed the German advance on Saint-Vith, costing the enemy valuable time and allowing American reinforcements to rush to the area.

Rigdon was initially declared missing in action as of December 21, 1944, along with the rest of the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments. He was identified by his dog tags and a portion of his service number in his overcoat. After the Allies defeated the offensive, Rigdon was buried at a temporary military cemetery in Foy, Belgium, on February 15, 1945. Despite that, he was held as missing in action until March 7, 1945.

Although Ridgon almost certainly was killed on December 18 or 19, 1944, the Army never went back to try to determine when specific soldiers from the two encircled regiments were killed. Thus, Rigdon and many other members of his regiment who fell those two days officially died on December 21, 1944.

Rigdon was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

In 1948, Rigdon’s father requested that his son be interred in a permanent military cemetery overseas. In accordance with his wishes, Rigdon was reburied in the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery in Belgium.

On December 21, 1962, the Wilmington Morning News carried a memorial item in his honor:

Loving memories never die, / As years roll on and days go by, / In my heart a memory is kept / Of one I loved and will never forget.

Sadly missed by Sister, May.

She placed another notice in The News Journal printed on December 21, 1994, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of her brother’s death:

We never lose the ones we love / For even though they’re gone / Within the hearts of those who care / Their memory lingers on

Loved and Sadly missed by sister May

Rigdon is honored on the Wall of Remembrance at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware, on the Harford County war memorial in Bel Air, Maryland, and on a cenotaph at Silverbrook Cemetery in Wilmington, Delaware, where his parents and sister were buried after their deaths.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo, to Brian J. Welke for information, and to Jim Wentz for documents.

Bibliography

Brock, Charlie A. “Report of Operations Against Enemy.” January 6, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Courtesy of Jim Wentz.

Caddick-Adams, Peter. Snow & Steel: The Battle of the Bulge, 1944–45. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Census Record for Paul H. Rigdon. April 22, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHQ-G9J

Census Record for Paul Rigdon. May 14, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9M1-CXV3

“Convoy AT.159.” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. https://www.convoyweb.org.uk/at/index.html?at.php?convoy=159!~atmain

“Dora May Hastings.” The News Journal, August 20, 2000. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187391015/

Draft Registration Card for Paul Howard Rigdon. June 30, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-XDWG

“Elsmere Soldier Killed in Action.” Wilmington Morning News, March 9, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187390007/

Enlistment Record for Paul H. Rigdon. February 28, 1944. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=42085071&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=8296307

“Former Harford Boy Missing in Action.” The Aegis, January 19, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187389712/

“General Orders No. 51.” Headquarters 106th Infantry Division. July 31, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Indiana Military.organization website. https://www.indianamilitary.org/106ID/AllGOs/45-GO-051.pdf

“Harold Rigdon.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/189010135/harold-rigdon

Headstone Inscription and Interment Record for Paul H. Rigdon. Headstone Inscription and Interment Records for U.S. Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942–1949. Record Group 117, Records of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1918–c. 1995. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9170/images/42861_646933_0808-01881

Hospital Admission Card for 42085071. December 1944. U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/706817420/rigdon-paul-h-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Paul H. Rigdon. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Jones, Alan W. Jr. “The Operations of the 423d Infantry (106th Infantry Division) In the Vicinity of Schonberg During the Battle of the Ardennes, 16–19 December 1944 (Ardennes–Alsace Campaign) (Personal Experience of a Battalion Operations Officer).” Undated, c. 1950. https://mcoecbamcoepwprd01.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/library/DonovanPapers/wwii/STUP2/G-L/JonesAlanWJr%20%20CPT.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 1229th Reception Center. February 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-02/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0339/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0339-04.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C” 53rd Infantry Training Battalion. July 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-07/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0384/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0384-03.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C” 53rd Infantry Training Battalion. March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0061/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0061-05.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 423rd Infantry Regiment. September 1944 – December 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-09/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0229/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0229-19.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086-12.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399-20.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-12/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481-10.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “D,” 1229th Reception Center. March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0003/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0003-12.pdf

Morrison, Don. “Memorial to county’s war dead dedicated.” The Aegis, May 30, 1985. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187390806/

“Rigdon.” The News Journal, December 21, 1994. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187390435/

“Rigdon.” Wilmington Morning News, December 21, 1962. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187390168/

Rigdon, May. Individual Military Service Record for Paul Howard Rigdon. March 22, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20517/rec/9

Silverman, Lowell. “Private Herbert Rubenstein (1923–1944).” Delaware’s World War II Fallen website. December 19, 2025. Updated December 21, 2025. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2025/12/19/private-herbert-rubenstein/

“Special Orders No. 209, Headquarters Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot No. 1.” July 27, 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-07/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0295/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0295-06.pdf

“Special Orders No. 242, Headquarters Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot No. 1.” August 29, 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-08/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0302/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0302-04.pdf

Last updated on December 27, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.