| Hometown | Civilian Occupations |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Worker for Bethlehem Steel |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 12100413 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Medical Detachment, 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 861 (surgical technician) | Rhineland campaign, Ardennes–Alsace campaign |

Early Life & Family

Herbert Rubenstein was born in Wilmington, Delaware, on September 22, 1923. Nicknamed Herb, he was the son of Morris Rubenstein (c. 1879–1942) and Mary Rubenstein (née Astrinsky, c. 1884–1938). His parents were Jewish immigrants born in Grodno. Prior to World War I, Grodno was part of the Russian Empire, though it is now part of Belarus. The family ran a delicatessen in Wilmington. Rubenstein had two older brothers and two older sisters.

As of February 17, 1926, when his father declared his intention to become a U.S. citizen, Rubenstein was living at 202 West 2nd Street in Wilmington with his family. They were at 420 West 22nd Street when they were recorded on the census in April 1930. His mother died from diabetic complications at Mount Sinai Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 5, 1938. At the time of the next census in April 1940, Rubenstein was living with his father and one of his sisters at 2520 Jefferson Street.

After graduating from Pierre S. duPont High School, Rubenstein enrolled in the College of Arts & Science at the University of Delaware, Class of 1945. Rubenstein performed the role of Philostrate in the E-52 student theater company’s May 1942 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He was also an associate editor of the yearbook and a member of the Sigma Tau Phi fraternity.

When he registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, Rubenstein listed his address as 2310 Washington Street in Wilmington, where his father was also living, though that was crossed off on an unknown date and replaced with 709 West 26th Street, where his brother, Harry Rubenstein (1906–1969), lived. His employer was listed as Bethlehem Steel, with the card noting that he was a student but temporarily working at the company’s Harlan Plant in Wilmington. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, 11 inches tall and weighing 160 lbs., with brown hair and gray eyes. Less than three months later, on September 17, 1942, Rubenstein’s father died of bronchopneumonia and stomach cancer at the Delaware Hospital in Wilmington.

Rubenstein completed two years of college before he was called to active duty.

Military Career

Rubenstein was a cadet in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps at the University of Delaware. He volunteered for the U.S. Army, enlisting in the Enlisted Reserve Corps in Newark on December 12, 1942.

At the end of his sophomore year of college, Rubenstein was called up to begin his training. He went on active duty on May 29, 1943, and was attached unassigned to Company “C,” 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey. On June 8, 1943, he was dispatched south for basic training.

On June 12, 1943, Private Rubenstein was attached unassigned to Company “A,” 60th Infantry Training Battalion, Infantry Replacement Training Center, Camp Wolters, Texas. After completing basic training, on September 20, 1943, Rubenstein and a group of men from his training unit were dispatched to attend the Army Specialized Training Program (A.S.T.P.) Basic course at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. There, on September 23, 1943, he was attached unassigned to Company “C,” 3312th Service Unit. His military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code was recorded at the time as 629, student. After completing a semester of accelerated classes, Private Rubenstein was authorized to visit Wilmington on furlough during January 2–9, 1944.

A.S.T.P. was supposed to provide the U.S. Army with soldiers with valuable skills in fields like languages, engineering, and medicine. In early 1944, due to a projected manpower shortage, Army planners decided to discontinue virtually the entire A.S.T.P. and transferred nearly all its personnel to other units. Private Rubenstein was among a group of A.S.T.P. men dispatched to the 106th Infantry Division at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, per Special Orders No. 6, Headquarters 3312th Service Unit, Army Specialized Training Unit, dated January 13, 1944, and effective on January 18, 1944. His M.O.S. code was recorded at the time as 745, rifleman. The 106th Infantry Division was commanded by Major General Alan Walter Jones (1894–1969).

Around January 19, 1944, Private Rubenstein joined Company “A,” 1st Battalion, 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division. On January 20, his company departed Fort Jackson by motor convoy, passed through Georgia, and arrived at the Tennessee Maneuver Area on the afternoon of January 23.

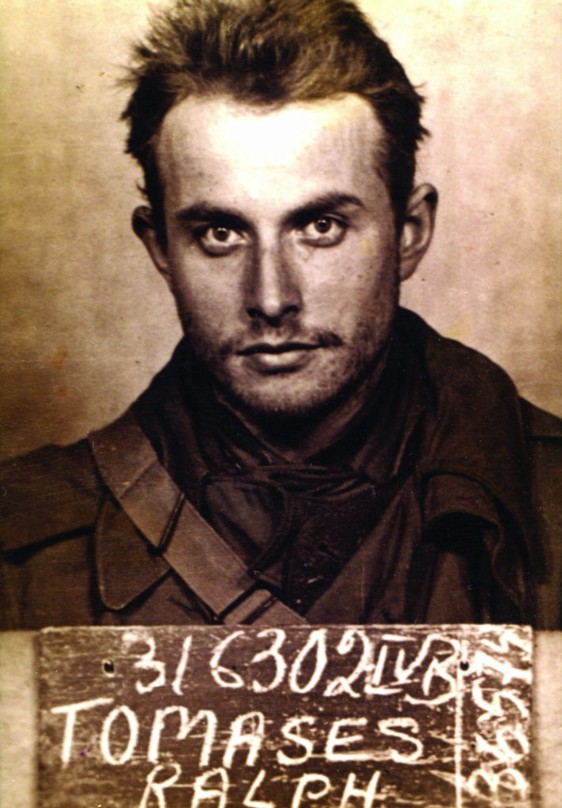

On March 24 or 25, 1944, Rubenstein transferred to Medical Detachment, 423rd Infantry Regiment. Another young Jewish soldier from Wilmington, Captain Ralph Tomases (1920–2009), was a dentist in the same regiment. In a 1990 letter he recalled that Rubenstein “grew up living across the street from my wife’s house” and they “knew each other and their families quite well. His brothers and sisters were friends with my family[.]”

In a 1992 oral history interview, Tomases recalled that he was involved in Rubenstein’s transfer from a rifle company to the medical detachment:

He was assigned to this 423rd Regiment sometime in January of 1944. And the family knew his address so they wrote to me and said, “Look him up.”

So, I found him over in 3rd [sic] Battalion. I don’t remember what company he was in. He was part of a mortar team. He used to carry this 60 lb. [sic] mortar plate on his back. And so, I thought I would do him a favor and I said, “Do you want to get in the medics?”

He said, “Sure.” So, I spoke for him. [The officer] said ok, he could become a medic. He’ll stay the same place he is. He’ll be a stretcher bearer. So, he traded one load for another.

The M2 60 mm mortar weighed only 42 lbs., so the baseplate did not weigh quite as much as Dr. Tomases recalled. He apparently conflated the caliber of the mortar with its weight.

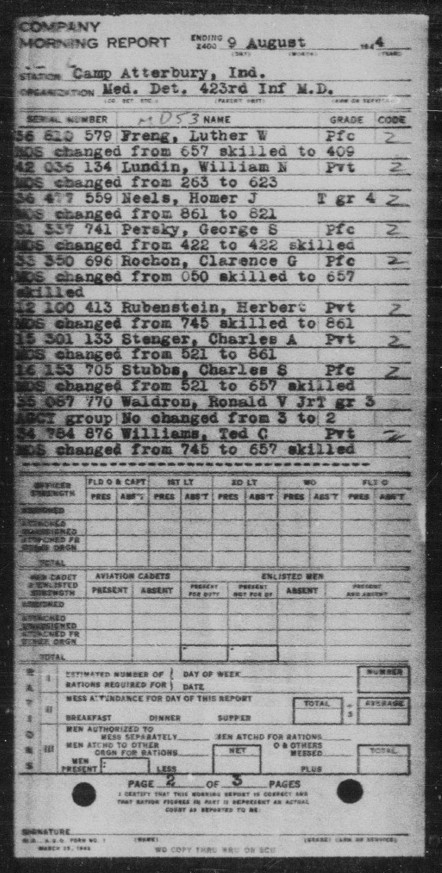

A morning report dated August 9, 1944, documented that Private Rubenstein’s M.O.S. code had changed from 745, rifleman, to 861, surgical technician, possibly effective that July. During World War II, the U.S. Army did not have an official M.O.S. of combat medic, but the surgical technicians from regimental medical detachments who were attached to platoons to provide medical care were informally known as medics. According to a 1945 letter by Gayle B. “Windy” Wingate (1921–1986), Private Rubenstein was attached to a platoon in Company “L,” part of 3rd Battalion. Medical detachments also had teams of stretcher bearers responsible for evacuation of casualties. Unless he served as one prior to his M.O.S. being reclassified, contrary to Dr. Tomases’s recollections, Rubenstein was not a stretcher bearer.

Another 423rd Infantry medic, Technician 5th Grade Richard Russell Ritchie (1924–2009), recalled in a 1992 letter to Dr. Tomases that “Herb was a good friend and I enjoyed his company very much.”

Ritchie wrote:

Herb and I were both infantry company Aidmen. While in training at Ft. Jackson and Camp Atterbury we were referred to as Pill rollers, Bedpan commando’s [sic], [canker] mechanic’s [sic] as well as Company First Aidmen. To us these were Derogatory references [except] First Aidmen. Not until we were overseas do I recall being referred to as a Medic.

On March 28, 1944, Rubenstein’s unit left the Tennessee Maneuver Area. After an overnight stop at Fort Knox, Kentucky, they arrived the following day at Camp Atterbury, Indiana.

Replacement training centers could not keep up with the casualties the U.S. Army was suffering, especially in Europe. The 106th Infantry Division’s departure overseas was repeatedly delayed and its cohesion diminished because the Army stripped thousands of men for use as replacements. Rubenstein made the most of the delays, going on furlough May 5–15, 1944, and again September 16–29, 1944.

On the morning of October 8, 1944, Rubenstein and the rest of his unit departed Camp Atterbury, arriving the following day at Camp Myles Standish, Massachusetts. On October 16, 1944, the 423rd Infantry moved to the New York Port of Embarkation, shipping out for the United Kingdom the following morning aboard the British ocean liner turned troop transport Queen Elizabeth. Steaming fast and unescorted, the ship pulled into the Firth of Clyde on October 22, 1944. They disembarked in Greenock, Scotland, on October 24, 1944, and moved south by rail, arriving early the following morning in Gloucestershire, England. Company “L” was based in Cheltenham (at the racecourse from November 7 onward according to morning reports), while Medical Detachment headquarters was at nearby Charlton Kings.

Private Rubenstein went on furlough November 10–13, 1944.

Early on December 1, 1944, the 423rd Infantry departed Gloucestershire via train, arriving that morning at Southampton. They shipped out for the continent by sea that same day.

Under the laws of war, soldiers were prohibited from intentionally targeting enemy medical personnel. On the Western Front, notwithstanding collateral damage due to limits in both visibility and the accuracy of weaponry, German soldiers generally adhered to these laws. As a result, American medics typically had red cross markings on their helmets and wore red cross brassards on one or both arms. Ritchie grimly noted: “As I learned later in the case of Herb Rubenstein and Lt. [Herbert] Blackburn these markings mean absolutely nothing in close combat.”

Combat in the Ardennes

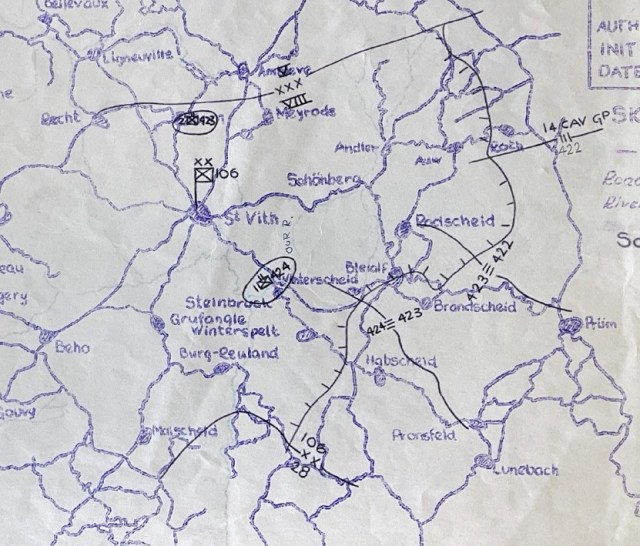

The 423rd Infantry disembarked at Le Havre, France, on December 3, 1944. Six days later, on December 9, 1944, the unit arrived by motor convoy at Saint-Vith, Belgium, where the division command post was set up. During December 10–12, 1944, the 106th Infantry Division took over defensive positions in the forested area of western Germany known as the Schnee Eifel, relieving the 2nd Infantry Division. On December 11, 1944, the 423rd Infantry crossed the border into Germany to take over their section of the front. The sector was quiet while American forces concentrated on taking the Roer dams and driving into the Saarland. The 422nd Infantry was the northernmost regiment on the division’s left, Rubenstein’s 423rd Infantry was in the center, and the 424th Infantry was further south on the division’s right.

Captain Alan Walter Jones, Jr. (1921–2014), who remarkably enough served in his own father’s division as a battalion operations officer during the upcoming battle, later recalled that the 423rd Infantry Regiment was responsible for covering a six-mile front with just two battalions and its regimental reserve consisted of only of “Elements of Service Company and Regimental Headquarters Company” rather than the customary battalion. He recalled: “In spite of the extreme discomfort of the cold, damp weather and inadequate winter clothing and the obviously extended and exposed position, morale was high. This was a quiet sector where men could learn rapidly but safely.”

Even with all three of its infantry regiments placed in the line, the division was spread dangerously thin, as were the units on its flanks. Normal doctrine was for a division to have two regiments in the line and one in reserve, but in this case the 106th Infantry Division’s most substantial reserve consisted of 2nd Battalion, 423rd Infantry. The lack of resources was partially due to the Allied broad front strategy exacerbated by logistical issues, such as long supply lines from French ports and delays in opening the port at Antwerp, Belgium.

Several other factors led to a disaster in the making. Allied intelligence largely failed to detect a German buildup in the Ardennes. Most intelligence officers—and for that matter, most Allied commanders—could simply not conceive of the possibility that the Germans would squander so much of their remaining strength with a counterattack that had absolutely no chance of attaining any major strategic objectives unless the Allies experienced the sort of collapse as had been suffered by France in 1940. The 106th Infantry Division’s commanding officer, Major General Jones, lacked combat experience and did not respond decisively to rapidly developing events. Division communications were dependent on wired lines which were disrupted during the first day of the battle.

Historian Steven J. Zaloga wrote that 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments

were positioned in a vulnerable salient on the Schnee Eifel, a wooded ridgeline protruding off the Eifel plateau. […] The area forward of the two regiments was very suitable for defense since it consisted of rugged forest with no significant roads. But it was flanked on either side by two good roads, from Roth to Auw, and Sellerich to Bleialf.

Those roads converged behind them to the west, meaning that if the enemy broke through traveling those roads, both regiments would quickly face encirclement. The road passing through Bleialf, Germany, on the 423rd Infantry’s right, was garrisoned only by Antitank Company, 423rd Infantry.

For several days, the 423rd Infantry’s activities were limited to patrolling and fending off German patrols. Captain Jones wrote: “Wheeled and tracked vehicle movements were reported by patrols on the nights of 14 and 15 December; the comment received by Corps concerning these reports was that the sounds heard were undoubtedly from enemy loudspeaker systems.”

On the morning of December 16, 1944, the Germans launched a massive counteroffensive through the Ardennes that came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge. The opening artillery bombardment disrupted the 423rd Infantry’s communications and destroyed a stockpile of ammunition. The enemy hit Antitank Company, 423rd Infantry, at Bleialf. A scratch force from the 423rd’s Cannon Company and Service Company, supplemented by a small number of combat engineers, tank destroyers, and field artillery, launched a successful counterattack, driving the enemy back.

According to Wingate, Private Rubenstein was attached to Company “L,” 3rd Battalion at the time the attack began. They received artillery fire but saw little sign of the enemy. Despite managing to hold its position while taking few casualties on the first day, the 106th Infantry Division’s situation was dire.

The sole regimental reserve, 2nd Battalion of the 423rd Infantry, had initially been deployed to Schönberg, Belgium, a crossroads to the west of the main body of the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments, but was committed to prop up the sagging left flank of the 422nd Infantry.

That evening, the division’s commander, Major General Jones consulted his superior, VIII Corps commander Major General Troy H. Middleton (1889–1976). Their phone connection was poor, and a catastrophic misunderstanding took place. Middleton ordered Jones to withdraw the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments, but Jones thought he had been instructed to keep them in place.

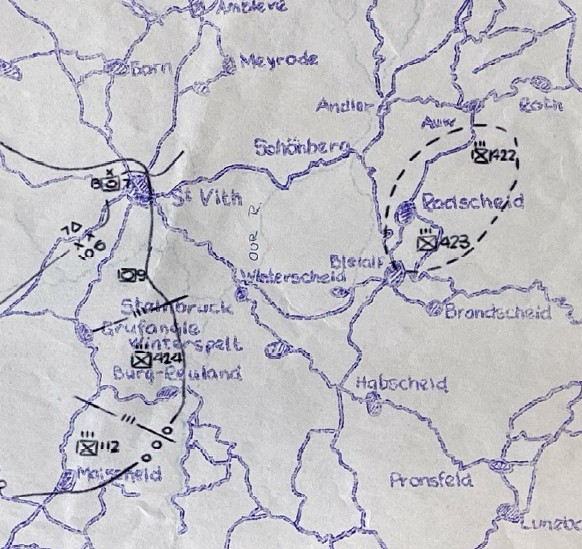

Early in the morning on the second day of the battle, December 17, 1944, a renewed enemy attack broke through at Bleialf. This southern pincer linked up at Schönberg with another pincer that had broken through the thinly spread 14th Cavalry Group to the north. Had 2nd Battalion, 423rd Infantry been able to remain in Schönberg, it might have held open an escape route for the two beleaguered regiments, or at the very least delayed their encirclement. Of course, it is by no means certain that even a regiment of inexperienced soldiers, much less a battalion, could have held the crossroads against a concerted enemy attack, though the fortunes of war are so unpredictable as to make counterfactuals fraught with peril. For instance, at nearby Lanzerath, Belgium, a single equally inexperienced American platoon held off multiple assaults for nearly a day, delaying an entire German division.

By that evening, the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments had been encircled, cutting them off from resupply. The enemy focused on continuing their drive westward rather than reducing the pocket and a breakout might have succeeded that day. However, the General Jones mistakenly believed that a relief force would arrive sooner than it did. He requested that supplies be delivered by air, but no such mission took place.

Zaloga wrote that on the morning of December 18, 1944, the 422 and 423rd Infantry Regiments received orders that they “should breakout towards St Vith, bypassing the heaviest German concentrations around Schönberg.” Later, these orders were changed to retake Schönberg and then withdraw to Saint-Vith. Ritchie recalled: “After destroying all our excess baggage (duffle bags and what was not necessary in battle) we moved toward Schonberg on the 18th of December.” They halted for the night southeast of Schönberg.

Zaloga wrote about the following day:

As the 423rd Infantry formed for its attack shortly after dawn on 19 December, it was hit hard by the German artillery, followed by an infantry assault. Two rifle companies reached the outskirts of Schönberg but were pushed back by German anti-aircraft guns.

Ritchie recalled it being a cold, partly cloudy day and that his platoon was on a low wooded ridge just southeast of Schönberg. Remarkably, he even remembered the “Strong smell of pine due to artillery shells that had hit the tree tops earlier in the day.”

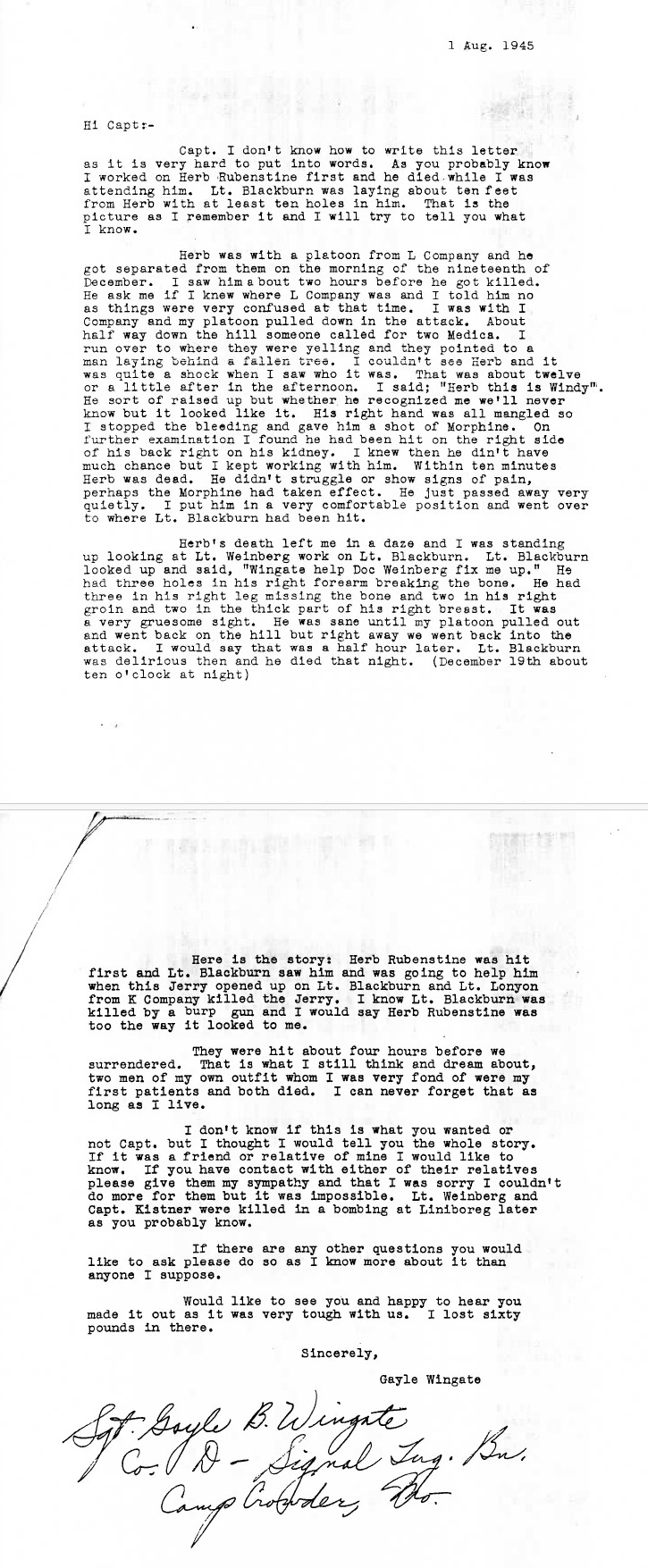

That morning, December 19, 1944, Rubenstein got separated from his platoon and encountered Technician 3rd Grade Wingate, who was serving with Company “I” in the same battalion. In a letter to Dr. Tomases, dated August 1, 1945, Wingate recalled that Rubenstein asked “me if I knew where L Company was and I told him no as things were very confused at that time.”

A few hours later, Technician 5th Grade Ritchie encountered Rubenstein. Decades later, he recalled:

We slowly and quietly worked our way to the edge of an open area. Before proce[e]ding across the open area we studied the situation ahead and spotted someone ahead and to our right. We waited a bit and I said don’t shoot it’s one of ours and he’s a medic. After he progressed a little further we could see he was waving a white object and “yelling [sic] don’t shoot all hell has broken loose up ahead.” At this point I could see it was Herb Rubenstien [sic]. At this point [neither] Herb nor did I or anyone else know what was ahead because of the trees, brush and knee high grass. […] I determined the direction Herb was moving and took a path under cover of bushes and trees in an attempt to intercept Herb. About halfway to the point of intercepting Herb all hell broke out shooting in front of me and both sides. I hit the ground and laid as flat as I could and waited until the shooting stopped.

Although neither man witnessed it, both Ritchie and Wingate were told soon afterward that a German soldier shot Private Rubenstein and then mortally wounded a doctor who tried to intervene, 1st Lieutenant Herbert Marfield Blackburn, II (1915–1944). An American soldier then gunned down the German. Ritchie later asked another soldier what had happened:

I was told that Herb when walking through the open Area [he] had kicked up a German in the grass and [the] German jumped up and shot Herb. Blackburn evidently witnessed the shooting and came out from cover to help Herb and at the same time shouting at the German saying, “he couldn’t shoot a Medic.” At this point the German turned and shot Blackburn.

Both Wingate and Ritchie agreed that the German had shot Rubenstein and Blackburn with an automatic weapon, probably a submachine gun (“burp gun”). Wingate recalled that “Lt. Lonyon from K Company killed the Jerry.” This must have been 2nd Lieutenant Robert Lee Lozon (1915–2000). On the other hand, Ritchie recalled being told that Company “K” commanding officer James Harman Bricker (1920– 2013) had avenged Rubenstein, Blackburn, and the unknown third soldier.

After the exchange of gunfire, other soldiers called for medics. Technician 3rd Grade Wingate rushed to Private Rubenstein’s aid, while Technician 5th Grade Ritchie crawled over to an unidentified rifleman who had suffered a fatal gunshot wound to the head.

Rubenstein lay mortally wounded next to a downed tree. Wingate recalled that “it was quite a shock when I saw who it was.” Rubenstein was semiconscious and barely responded when Wingate said, “Herb, this is Windy.” Wingate wrote later:

He sort of raised up but whether he recognized me we’ll never know but it looked like it. His right hand was all mangled so I stopped the bleeding and gave him a shot of Morphine. On further examination I found he had been hit on the right side of his back right on his kidney. I knew then he didn’t have much chance but I kept working with him. Within ten minutes Herb was dead. He didn’t struggle or show signs of pain, perhaps the Morphine had taken effect. He just passed away very quietly. I put him in a very comfortable position and went over to where Lt. Blackburn had been hit.

Wingate wrote that “Herb’s death left me in a daze and I was standing up looking” on as 1st Lieutenant Ernest Daniel Wenberg (1916–1944) worked desperately to treat Lieutenant Blackburn. Blackburn had been riddled with as many as 10 rounds on the right side of his body, with wounds to forearm, chest, groin, and right leg. Remarkably, Blackburn was still conscious and it was he who snapped Wingate out of it by saying, “Wingate, help Doc Wenberg fix me up.”

Ritchie’s account, written 47 years after Wingate’s, differs in a few details. Wingate recalled that Rubenstein was hit around noon or early afternoon on December 19, 1944, while Ritchie believed it was roughly between 1030 and 1130 hours. Ritchie did not mention Wingate at all, stating that after assessing the slain rifleman, Ritchie crawled over to and examined Rubenstein. Rubenstein was unresponsive and no longer bleeding, suggesting that he was already dead. Still, Ritchie wrote that he applied sulfa powder, bandages, and an emergency medical tag. He stated that he then began caring for Lt. Blackburn and then helped Lieutenant Wenberg after the latter began treating him.

Lieutenant Blackburn had just become a father one month earlier, once he was already overseas. Nearly half a century later, Ritchie still recalled his heartbreaking lament: “I’ll never get to see that little baby girl of mine.” Blackburn succumbed to his wounds that night. Lieutenant Wenberg died a few days later as a prisoner of war, reportedly after he was caught in an air raid.

Rubenstein’s burial report listed the cause of death as penetrating trauma to the face and skull, though both Wingate and Ritchie agreed that he suffered mortal gunshot wounds to the abdomen. This raises the disturbing possibility that when graves registration personnel retrieved the bodies, they confused Rubenstein’s body with that of the unidentified soldier that Ritchie had treated, though Rubenstein’s burial report states he was identified by his dog tags.

Their ammunition exhausted, virtually all the men in the 423rd Infantry Regiment were forced to surrender later that afternoon. Together with the loss of the 422nd Infantry, it was the largest surrender of American forces in the European Theater during the entire war. However, their brief stand had delayed the German advance on Saint-Vith, costing the enemy valuable time and allowing American reinforcements to rush to the area.

Ritchie, Wingate, and Tomases were among those who became prisoners of war but were liberated at war’s end. Although Wingate and Ritchie’s accounts make it clear that Rubenstein was killed before the surrender on December 19, 1944, the main bodies of both regiments were declared missing in action as of December 21. That later became his official date of death, even though it was erroneous. Likewise, Lieutenant Blackburn’s date of death was not corrected, and his official date of death is also December 21. Rubenstein’s headstone was eventually corrected, possibly due to Tomases’s research, but Blackburn’s was not.

Wingate told Dr. Tomases in his 1945 letter that he lost 60 lbs. in less than six months as a prisoner of war. He was haunted by the deaths of Rubenstein and Blackburn, writing:

They were hit about four hours before we surrendered. That is what I still think and dream about, two men of my own outfit whom I was very fond of were my first patients and both died. I can never forget that as long as I live.

After Allied forces defeated the Ardennes offensive, Private Rubenstein’s body was buried in a temporary military cemetery in Foy, Belgium, on February 11, 1945. The War Department continued to hold him as missing in action until his status was changed to killed in action on March 3, 1945. After the war, in 1948, Harry Rubenstein requested that his brother’s body be repatriated to the United States. The following year, his casket returned to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the Liberty ship Barney Kirschbaum. On April 8, 1949, a military escort accompanied the body by train from Jersey Central to Wilmington, arriving at 1610 that afternoon.

Following services at the Chandler Funeral Home in Wilmington on April 10, 1949, Rubenstein was buried in the Jewish section of Lombardy Cemetery in Wilmington, now known as the Jewish Community Cemetery.

Private Rubenstein was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and would have retroactively been eligible for the Combat Medical Badge, though there is no evidence he was ever awarded it.

Rubenstein’s name is honored on memorials at the Jewish Community Cemetery, at the University of Delaware, and on the Wall of Remembrance at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Notes

Date Rubenstein Joined the 423rd Infantry

The Company “A” 423rd Infantry morning report for February 5, 1944, stated that Rubenstein joined the company on January 13, 1944. This evidently conflated the date of the transfer order with the date he joined, since his previous unit’s morning reports show that Rubenstein did not leave Baltimore until January 18.

Unidentified Rifleman

The identity of the rifleman who Ritchie stated was shot in the head and killed around the same time that Rubenstein was shot is unclear. A roster of 181 men from the company who were missing in action was documented in a Company “K” morning report on December 21, 1944. All were documented as prisoners of war with one exception: Private 1st Class Charles Michael Spencer (1918–1944) was killed in action. However, just as Private Rubenstein was a medic attached to Company “L” who ended up separated from the unit, it is entirely possible that the man Ritchie assessed came from another unit other than Company “K.”

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr. Ralph Tomases’s daughters, Faith Tomases and Ruth Tomases Joffe, the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware, the University of Delaware, the 106th Infantry Division Association, Carl Wouters, Jim Wentz, Brian J. Welke, and Martin Kloosterman for contributing information, documents, and photos.

Bibliography

106th Infantry Division. 1944. Courtesy of the 106th Infantry Division Association. https://www.106thinfdivassn.org/album/423med.jpg

The 1943 Blue Hen. 1943. Courtesy of the University of Delaware. https://udspace.udel.edu/bitstreams/3261da17-992e-45e3-b1e4-2599df3d390c/download, https://udspace.udel.edu/bitstreams/3de45249-3fbc-4725-9979-8c4e77ecbec0/download

Barron, Paul J. Letter to Ralph Tomases. July 24, 1945. Courtesy of Faith Tomases, Ruth Tomases Joffe, and the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware.

Brock, Charlie A. “Report of Operations Against Enemy.” January 6, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Courtesy of Jim Wentz.

Caddick-Adams, Peter. Snow & Steel: The Battle of the Bulge, 1944–45. Oxford University Press, 2015.

“Capt. J. H. Bricker Expected Home.” Plainfield Courier-News, June 6, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/182152977/

Census Record for Herbert Rubenstein. April 4, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MR-M3Q4

Census Record for Herbert Rubenstein. April 14, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRHM-NX6

Certificate of Death for Mary Rubeinstein. June 1938. Death Certificates, 1907–1970. Record Group 19, Series 11.90, Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/5164/images/42342_2421406272_0712-00535

Certificate of Death for Morris Rubenstein. September 17, 1942. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6MZN-5F

“Col Alan Walter ‘Bunt’ Jones Jr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/138593264/alan-walter-jones

Declaration of Intention for Citizenship for Morris Rubenstein. February 17, 1926. Naturalization Petitions of the U.S. District and Circuit Courts for the District of Delaware, 1795–1930. Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1193/images/M1644_17-0032

Draft Registration Card for Herbert Rubenstein. June 30, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-X9ZD-D

Enlistment Record for Herbert Rubenstein. December 12, 1942. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=929&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=12100413&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=31911

“Gayle B Wingate.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17445992/gayle-b-wingate

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Herbert Rubenstein. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Jones, Alan W. Jr. “The Operations of the 423d Infantry (106th Infantry Division) In the Vicinity of Schonberg During the Battle of the Ardennes, 16–19 December 1944 (Ardennes–Alsace Campaign) (Personal Experience of a Battalion Operations Officer).” Undated, c. 1950. https://mcoecbamcoepwprd01.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/library/DonovanPapers/wwii/STUP2/G-L/JonesAlanWJr%20%20CPT.pdf

“Lieut. Blackburn Killed in Action In Europe Battle.” Plainfield Courier-News, March 27, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187092010/

“Memorial Services for Lt. Wenberg on Sunday.” The Green Bay Press-Gazette, February 9, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/187040515/

“A Midsummer-Night’s Dream Hits Stage In Mitchell Hall Tonight; Kronacher Production Promises to Entertain All.” The Review, May 15, 1942. https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/9de349b4-f927-4838-af37-59d63089e159/content

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 60th Infantry Training Battalion. September 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0069/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0069-04.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 423rd Infantry Regiment. January 1944 – March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0335/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0335-16.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-02/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0192/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0192-18.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0137/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0137-25.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 1229th Reception Center. June 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2843/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2843-06.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2843/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2843-07.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 3312th Service Unit, Army Specialized Training Unit. January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/460161878?objectPage=99, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/460161878?objectPage=114, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/460161878?objectPage=138

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 3312th Service Unit, Army Specialized Training Unit. September 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0023/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0023-16.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “K,” 423rd Infantry Regiment. October 1944 – December 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086-14.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399-22.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-12/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481-12.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “L,” 423rd Infantry Regiment. October 1944 – December 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086-14.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086-15.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399-22.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-12/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481-12.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-12/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481-13.pdf

Morning Reports for Medical Detachment, 423rd Infantry Regiment. March 1944 – December 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0137/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0137-29.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-04/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0081/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0081-18.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-05/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0387/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0387-20.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-05/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0387/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0387-21.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-06/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0021/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0021-26.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-07/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0069/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0069-04.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-07/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0069/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0069-05.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-08/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0057/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0057-31.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-08/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0057/85713825_1944-08_Roll-0057-32.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-09/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0229/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0229-23.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-09/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0229/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0229-24.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0086-15.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0399-23.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-12/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0481-13.pdf

Morning Reports for Trainees, Company “A,” 60th Infantry Training Battalion. June 1943 – July 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2006/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2006-28.pdf

“Morris Rubenstein Dies After Long Illness.” Journal-Every Evening, September 17, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/182478356/

“Richard Russell Ritchie.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/65868782/richard-russell-ritchie

“Pfc. Herbert Rubenstein.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53936723/herbert-rubenstein

“Pvt. Herbert Rubenstein.” Journal-Every Evening, April 7, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/article/182482090/

Ritchie, Richard R. Letter to Ralph Tomases. August 10–20, 1992. Courtesy of Faith Tomases, Ruth Tomases Joffe, and the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware.

“Robert Lee Lozon.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/157832263/robert-lee-lozon

Rubenstein, Harry. Individual Military Service Record for Herbert Rubenstein. July 22, 1949. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20606/rec/1

Tomases, Ralph. Interview by Garry Greenstein. March 27, 1992. Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. https://jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/items/show/339

Tomases, Ralph. Letter to Richard R. Ritchie. August 6, 1990. Courtesy of Faith Tomases, Ruth Tomases Joffe, and the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware.

Wingate, Gayle. Letter to Ralph Tomases. August 1, 1945. Courtesy of Faith Tomases, Ruth Tomases Joffe, and the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware.

Last updated on January 10, 2026

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.