| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware, Maryland | Worker for Agar Poultry Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 33390122 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Company “C,” 1st Ranger Infantry Battalion |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 610 (antitank gunner) | Anzio/Battle of Cisterna |

Early Life & Family

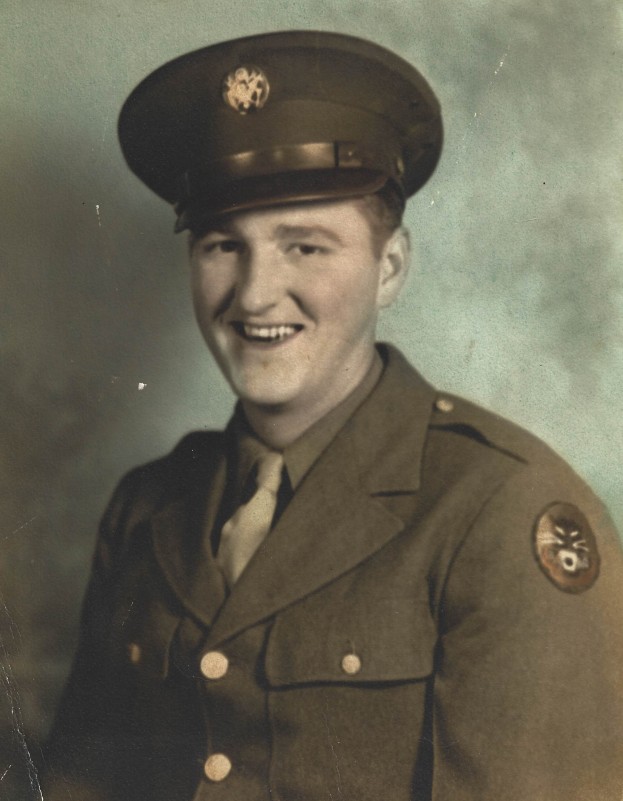

William Robert McCabe was born in Selbyville, Delaware, on the morning of October 19, 1922. He was the first child of Joseph McCabe (a farmer, 1903–1928) and Emma Gibson McCabe (née Lynch, 1905–1979). He had two younger sisters: Betty McCabe (1927–2016) and Josephine McCabe (later Mariner, 1928–2008).

On January 15, 1928, while McCabe’s mother was pregnant with McCabe’s youngest sister, McCabe’s father was admitted to Beebe Hospital in Lewes, Delaware, with typhoid fever. He lingered for over a week before dying on January 23. McCabe was just five years old.

McCabe was recorded on the census in April 1930 living with his mother and two younger sisters on Green Street in Frankford, Delaware. As of April 1, 1940, he was recorded on the census living with his mother and sister, Betty, in Frankford. McCabe was described as a laborer who had been out of work for the last 32 weeks, while his mother was working at a poultry company.

When he registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, McCabe was living on Graham Avenue in Berlin, Worcester County, Maryland, and working for the nearby Agar Poultry Company. The registrar described him as standing five feet, 11 inches tall and weighing 191 lbs., with red hair and brown eyes. His enlistment data card described his job as being in the category of “unskilled nonprocess occupations in manufacturing.”

The 1940 census stated that McCabe had finished only the 8th grade, while his enlistment data card stated that he completed three years of high school. He was Protestant.

McCabe married Irene Frances Timmons (1924–1999) on an unknown date between April 1, 1940, and to December 18, 1942. The couple had one son, William Frankie McCabe (1942–2011).

Military Career

After he was drafted, McCabe joined the U.S. Army in Baltimore, Maryland, on December 18, 1942. There are few details about the first nine months of his career, though it appears he attended basic training at Camp Hood, Texas. He most likely went overseas in the summer or fall of 1943.

Private McCabe’s name appeared on a list of Tank Destroyer replacements earmarked for the U.S. Fifth Army per Sailing (Passenger) List No. 92. His military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code was recorded as 610, antitank gunner. The group of 184 men was attached unassigned to and joined Company “A,” 29th Replacement Battalion in Italy, on October 2, 1943. At some point, he went on detached service with that battalion’s 3rd Provisional Guard before rejoining Company “A” on January 10, 1944. In a shuffle the following day, he was transferred to Company “A,” 23rd Replacement Battalion, under the umbrella of Personnel Center No. 6, 2nd Replacement Depot.

On January 15, 1944, Private McCabe joined Company “C,” 1st Ranger Infantry Battalion, at Lucrino, Italy. The 1st Ranger Battalion was activated in the United Kingdom with a group of handpicked volunteers, intending to create a special unit modeled on the British Commandos. Rangers attached to Commonwealth forces during the Dieppe Raid on August 19, 1942, were the first members of the U.S. Army to engage the Germans in ground combat during World War II.

The Rangers distinguished themselves in combat in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy, but suffered heavy losses. Although there were several short-lived Ranger schools stateside during the war, these were intended to provide valuable combat training that students would bring back to their own units, rather than serving as a pipeline to provide specially trained replacements to those Ranger units already overseas. There is no indication that McCabe had any Ranger training prior to joining the 1st Ranger Battalion.

Ranger units were smaller than conventional infantry units. When Private McCabe joined, Company “C” had just three officers and 82 enlisted men, less than half the complement of a full-strength regular rifle company. These lean units were intended for raids and other special missions, using infiltration and the element of surprise to compensate for their limited numbers.

McCabe’s new comrades must have introduced him to the Ranger way of combat. No matter how intensive that training was, one week was not enough to prepare a green soldier straight from basic training, especially one whose training had focused on preparing him to be a gunner on a tank destroyer.

Combat at Anzio

Italy had once been part of the Axis, but the Germans occupied most of the country in September 1943 after their former Allies sued for peace and the Allies landed in southern Italy in September 1943. The narrow peninsula with a mountainous interior was a defender’s dream. At the end of 1943, the Allies were halted at the Gustav Line south of Rome.

One area where the Allies enjoyed clear superiority over the Axis was naval strength and amphibious capabilities. By landing up the coast—in the end, they decided on Anzio—the Allies could potentially cut off the German forces manning the Gustav Line, destroying them or at least forcing them to withdraw. The main question was whether the Allies could build up sufficient forces to do so before German reserves from further north could respond.

On January 20, 1944, McCabe and his unit boarded the British transport H.M.S. Princess Beatrix, a veteran of numerous special amphibious operations. The following day, they sailed from the Gulf of Pozzuoli. For McCabe and the others, it was a sleepless night. At 2230 hours they began getting ready to disembark. Around midnight they began boarding their landing craft. McCabe’s company was in the first wave.

H-Hour at Anzio, was set for 0200 hours on January 22, 1944, and the force landed on schedule. The Anzio campaign would last for over four months and cost thousands of lives, but the initial landing was a cakewalk. The Rangers and attachments achieved surprise and quickly overwhelmed the few German soldiers present. Company “C” took no casualties and the main body of the Allied force soon landed. Despite the auspicious start, the Germans quickly managed to bottle up the invasion force.

Major General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. (1895–1965), one of the officers behind the development of the Ranger Force, devised a plan to take the key crossroads of Cisterna di Littoria (now Cisterna di Latina) and push on to the Alban Hills. Under cover of darkness, the 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions would infiltrate and hold Cisterna until relieved by the 4th Rangers and 15th Infantry Regiment and accompanying armor. The mission was dependent on speed and stealth. Aside from a drainage ditch, there was no cover along the infiltration route until Cisterna. If discovered by German sentries or revealed by flares or dawn, the Rangers would be caught in the open. A 24-hour delay had dire consequences, as the Germans reinforced Cisterna without Allied intelligence discovering it.

Sources differ as to whether Ranger Force commander Colonel William O. Darby (1911–1945) had misgivings about the plan, but he approved it without raising objections to General Truscott.

Around 0100 hours on January 30, 1944, the infiltration force moved out, led by Private McCabe’s 1st Rangers. It was slow going in the dark and the two battalions got separated. They hid when flares went up, but it slowed them down. The Rangers silently and ruthlessly eliminated German sentries with their knives. In the meantime, the forces that were supposed to push through to link up with them were discovered. A pitched battle broke out and the 4th Rangers and 15th Infantry were unable to make headway. The 1st and 3rd Rangers were on their own.

As dawn broke, about six hours into the infiltration, the 1st Rangers had not yet reached Cisterna. All hell broke loose when the Germans discovered the infiltrators behind their lines. A close quarters firefight broke out, and the Rangers were quickly surrounded. Lieutenant Colonel Carlo D’Este (1936–2020) wrote in his book, Fatal Decision: Anzio and the Battle for Rome:

The remainder of the two battalions were strung out in a long column, either in the ditch or in the open. Battles cannot be effectively fought from a column and it was from this awkward formation that the Rangers had to defend against the deadly attacks that were now directed their way.

The Germans launched an armored counterattack with tanks and self-propelled guns. Lacking their own tanks, the Rangers fought back with bazookas and sticky grenades and managed to knock out some, but they were greatly overmatched in both numbers and firepower. The 1st and 3rd Ranger battalions continued to fight bravely for hours but could not break out and their ammunition dwindled.

As the battle neared its conclusion around noon, some German soldiers resorted to a war crime. Using captured Rangers as human shields, they marched toward pockets of resistance, demanding their surrender. When some of the Rangers continued to resist, the Germans summarily murdered some of their hostages in full view of the American positions. Eventually, except for a handful who managed to escape, all the Rangers were captured or killed.

Considering the ferocity of the battle, Ranger fatalities were relatively low. According to research by Julie Foley Belanger, the 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions lost a total of 54 men killed in action or died of wounds, with at least 654 ending up in prisoner of war camps.

Private McCabe was among the Rangers killed at Cisterna. There are no known eyewitness accounts of his death and no clues in his burial report as to how he was killed.

Many histories state that only six Rangers from the 1st and 3rd escaped Cisterna without being captured. Actual figures are uncertain but somewhat higher. Belanger notes that about 35 Rangers, 17 of them wounded, avoided capture. About 23 men also managed to escape soon after capture. These are approximate figures, but it is clear that the 1st and 3rd Rangers took about 95% casualties during the battle, mostly captured. The 4th Rangers, which had tried unsuccessfully to break through to Cisterna, lost 20 men killed and 43 wounded. These Ranger Force losses were prohibitive and the remainder of 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Battalions were disbanded soon afterward.

General Truscott later wrote in his book, Command Missions, that the Fifth Army commander, Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark (1896–1984), was furious about the near annihilation of two Ranger battalions.

There was quite a flap when I reported to General Clark by telephone that night the loss of the Rangers. He came to see me the next morning and implied that they were unsuitable for such missions. I reminded him that I had been responsible for organizing the original Ranger battalion and that Colonel Darby and I perhaps understood their capabilities better than other American officers. He said no more. However General Clark feared unfavorable publicity, for he ordered an investigation to fix the responsibility. That was wholly unnecessary for the responsibility was entirely my own, especially since both Colonel Darby and I considered the mission a proper one, which should have been well within the capabilities of these fine soldiers. That ended the matter.

Subsequent historians also questioned whether the attack on Cisterna was beyond the Rangers’ capabilities. However, in his 2004 thesis, The Ranger Force at the Battle of Cisterna, Major Jeff R. Stewart argued that “In order to declare misuse of the Rangers, it must first be established what their proper use would be. […] Yet no doctrine for the use of the Rangers was ever written during World War II.”

A contemporary Ranger Force report suggested that, based on interrogation by prisoners of war, “that our attack on Cisterna was expected by the enemy” which suggested that the Germans had laid a trap for the Rangers.

On the contrary, Stewart argued: “The allegations of a German ambush have long been a part of the Cisterna myth. Some of the Ranger veterans felt that the German reaction was too strong and well coordinated to be a simple counterattack.” Stewart argued that “German sources make no mention of a deliberate ambush or a trap.”

That the Germans anticipated an attack on Cisterna is not the same thing as planning to ambush a large infiltration-style attack. The ambush theory ascribes an undeserved clairvoyance to the Germans, especially since, as Stewart observed, “Specific targeting of the Rangers based on their previous employment may also be discounted, since the Rangers are not even mentioned in the German intelligence summaries until 31 January 1944.” Furthermore, what happened at Cisterna was consistent with ordinary German defensive doctrine in which the front line might be lightly held but any penetrations subjected to aggressive counterattack.

In a sense, the Rangers were victims of their own success. Had sentries spotted them and raised the alarm sooner, before they infiltrated so deeply behind German lines, they would have been forced to retreat. There would have been casualties, but certainly fewer than occurred during actual events.

In that light, some later scholarship which blamed the influx of replacements like Private McCabe for the failure of the mission was deeply unfair. Stewart concluded: “While the training and experience level of the new Rangers was certainly not equal to that of the veterans, they acquitted themselves well during the battle and no evidence exists that the infiltration was compromised.”

Private McCabe was initially buried a little over a mile south of Cisterna near 41° 34’ 12” North, 12° 49’ 33” East, presumably close to where he fell. On September 5, 1944, he was reburied at an American military cemetery at Nettuno.

After the war, on May 5, 1947, Irene McCabe requested that her husband remain in a permanent military cemetery overseas. She subsequently changed her mind and on March 22, 1948, requested her husband’s body be repatriated to the United States. His casket was shipped from Naples, Italy, to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the Carroll Victory. The body arrived in Frankford, Delaware, on July 27, 1948. He was buried at Carey’s Cemetery there.

Notes

Transfers

Existing documentation for McCabe’s movements in January 1944 is contradictory. Several copies of an extract of Special Order No. 13, Headquarters 2nd Replacement Depot, dated January 13, 1944, stated that McCabe was being transferred to the 1st Armored Division. A morning report from Company “A,” 23rd Replacement Battalion stated that McCabe and three other men were transferred to the 1st Special Service Force on January 15, 1944. This is a curious detail, because that was another special unit like the Rangers, though there is no evidence that he joined that unit first. Interestingly, the Company “C,” 1st Ranger Infantry Battalion morning report cited Special Order No. 13 as assigning McCabe to the company, though all known copies of the order—at least extracts of it—list McCabe as being transferred to other units than the Rangers.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Private McCabe’s granddaughter, Ginger McCabe Davis, for the use of her photos, and to Rich Rayne for submitting his name, which had long been overlooked by scholars compiling lists of Delaware fallen. Thanks also go out to Julie Foley Belanger and Ron Hudnell for providing documents and information.

Bibliography

Atkinson, Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944. Henry Holt and Company, 2007.

Bahmanyar, Mir. The Houdini Club: The Epic Journey and Daring Escapes of the First Army Rangers of WWII. Diversion Books, 2025.

Belanger, Julie Foley. Email correspondence on November 3, 2025.

“Betty McCabe.” Delaware Wave, April 19, 2016. https://www.newspapers.com/article/183559560/

Briscoe, Charles H. “Commando & Ranger Training Part II, Preparing America’s Soldiers for War: The Second U.S. Army Ranger School & Division Programs.” Veritas, 2016 (Volume 12, No. 1). https://arsof-history.org/pdf/v12n1.pdf

Census Record for William R. McCabe. April 14, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9R4Z-2R7

Census Record for Wm. R. McCabe. May 8, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9MR-M9VB

Certificate of Birth for William R. McCabe. October 1922. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DYQ9-3W3

Certificate of Death for Joseph McCabe. 1928. Record Group 1500-008-092, Death Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6PQ3-TC2

D’Este, Carlo. Fatal Decision: Anzio and the Battle for Rome. HarperCollins, 1991.

Draft Registration Card for William R. McCabe. June 30, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for Maryland, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS7H-79V9-X

Enlistment Record for William R. McCabe. December 18, 1942. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=33390122&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3868875

Individual Deceased Personnel File for William R. McCabe. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

“Josephine McCabe Mariner.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/51834810/josephine-mariner

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 23rd Replacement Battalion. January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0493/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0493-26.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0493/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0493-27.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 29th Replacement Battalion. January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0565/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0565-02.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0565/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0565-03.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 29th Replacement Battalion. October 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-10/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0599/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0599-14.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 1st Ranger Battalion. January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0498/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0498-29.pdf

“Pvt. William Robert McCabe.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104875986/william-robert-mccabe

“Report of Action for period 22 Jan 1944 – 5 Feb 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Courtesy of Ron Hudnell.

“Robert Edward Ehalt.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/616959/robert-edward-ehalt

Stewart, Jeff R. The Ranger Force at the Battle of Cisterna. 2004. U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Master’s Thesis. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA428671.pdf

Truscott, Lucian K. Command Missions: A Personal Story. Originally published in 1954, republished by Arcadia Press, 2017.

Last updated on November 30, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.