| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Germany, Pennsylvania, Delaware | Box factory worker, surveyor |

| Branch | Service Number |

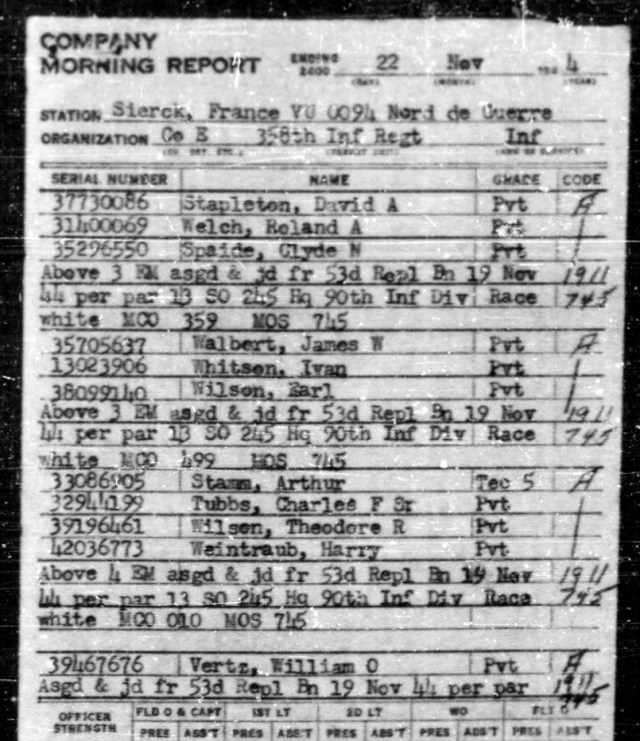

| U.S. Army | 33086905 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “E,” 358th Infantry Regiment, 90th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 745 (rifleman) | Rhineland campaign |

Early Life & Family

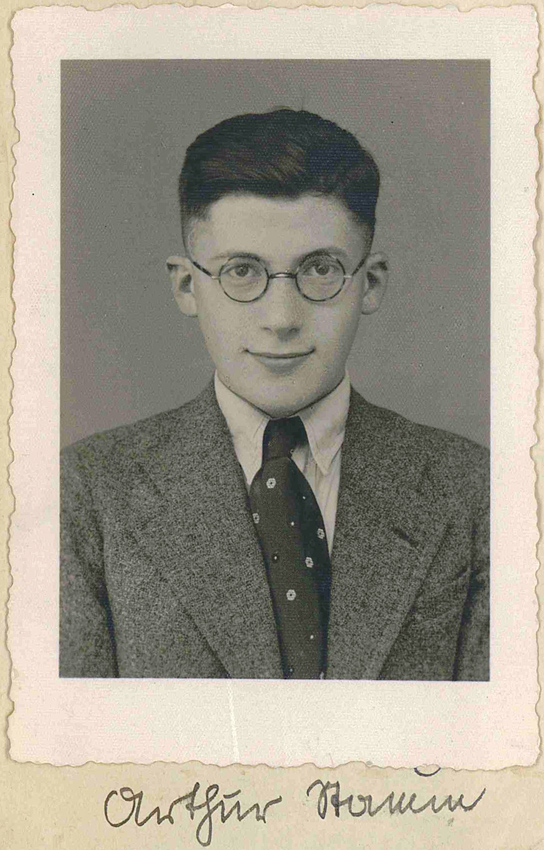

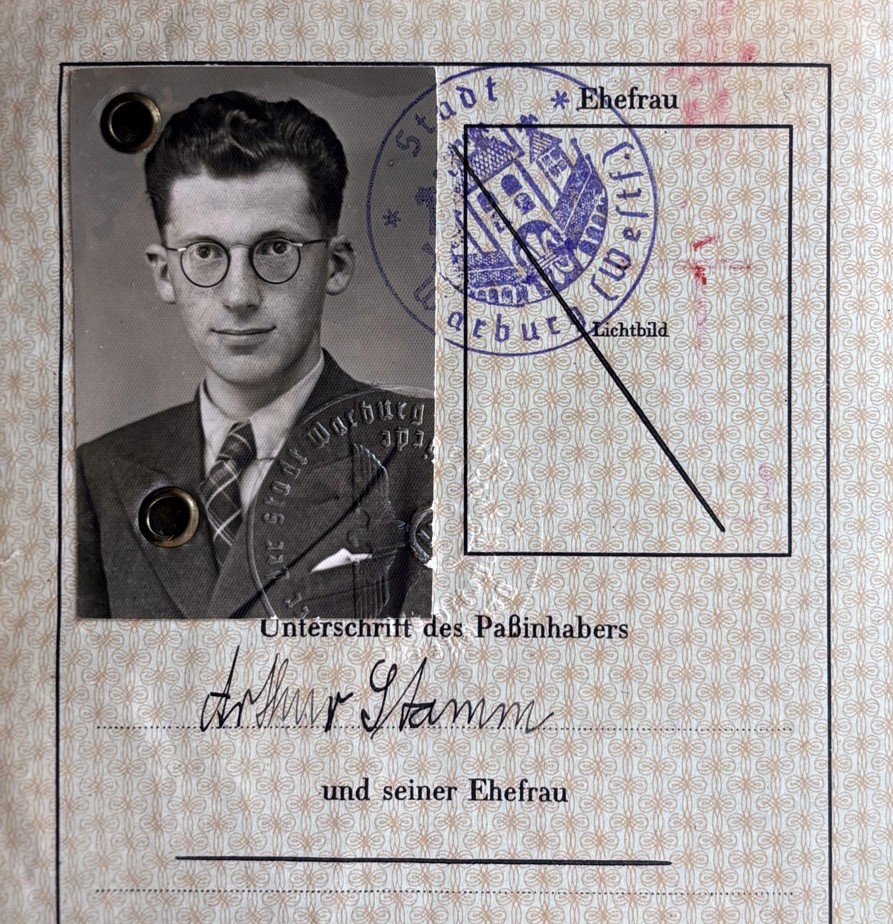

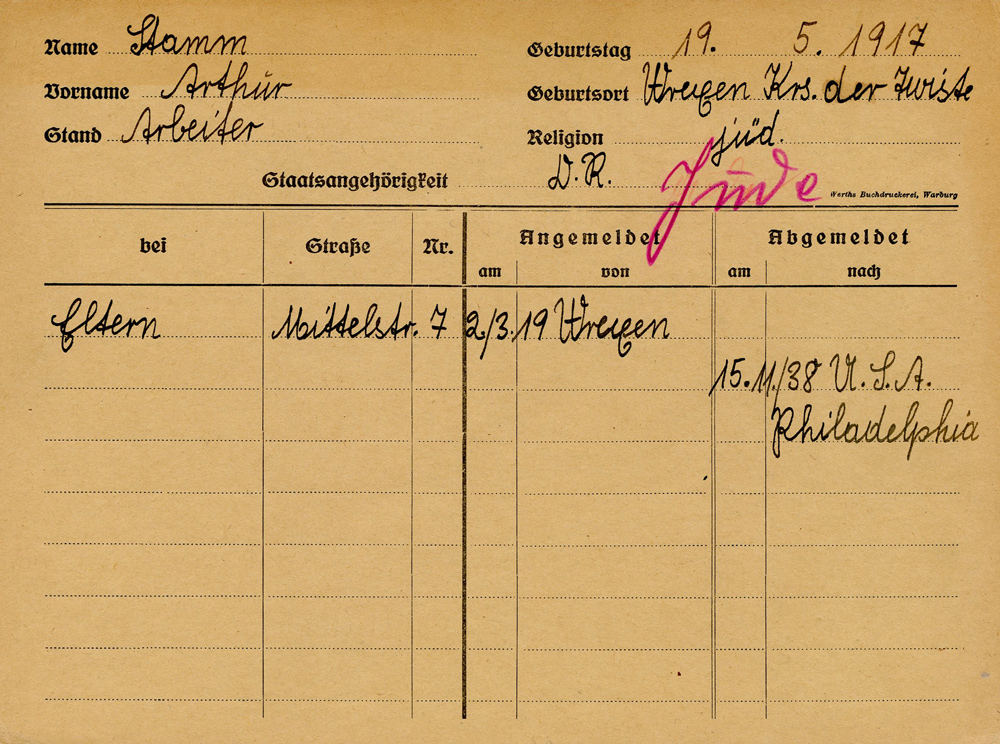

Arthur Stamm was born in Wrexen, Germany, on May 19, 1917. He was the second child of Louis Stamm (a livestock dealer, 1882–1942) and Alwine Stamm (née Löb, 1881–c. 1943). He had an older sister, Ilse Stamm (later Lowell, 1915–2004); a younger brother, Fritz Stamm (known as Fred L. Stamm after emigrating to the United States, 1919–2000); and a younger sister, Edith Stamm (1921–c. 1943). The Stamm family was living at Mittelstraße 7 (now Josef-Wirmer-Straße 7) in Warburg, Germany, by 1938.

As German Jews, the Stamms had lived through the same post-World War I upheavals as the rest of the country, only to endure increasingly virulent antisemitic laws enacted after the Nazis came to power in 1933.

American immigration law gave a larger quota to German immigrants than all countries aside from the United Kingdom but only a fraction of the prospective German Jewish immigrants who sought a visa were granted one. After an application process that took as long as two years, Stamm was lucky enough to obtain a visa to enter the United States from the consulate in Stuttgart, Germany, on October 21, 1938.

Shortly after Stamm obtained his visa, on the night of November 9–10, 1938, the Nazis unleashed a wave of violence against Jews which came to be known as Kristallnacht (literally Crystal Night, but commonly referred to as the Night of Broken Glass in English-speaking countries). In Warburg, the Nazis sacked the synagogue as well as Jewish-owned homes and businesses.

Weeks later, on November 24, 1938, Stamm sailed from Hamburg, Germany, aboard the S.S. Hamburg, arriving in New York City on December 2. He settled in Philadelphia, where his sponsor, Dr. Camille Joseph Stamm (1886–1964), lived. Dr. Stamm, a cousin of Stamm’s father, had served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps in France during World War I.

Stamm’s brother, Fred, a cabinetmaker, arrived in New York City on February 26, 1939. Both brothers applied for U.S. citizenship soon after the outbreak of World War II in Europe. On October 19, 1939, in Philadelphia, Stamm declared his intention to become an American citizen, although he was not naturalized for several years afterward. At the time of his petition, Stamm was living with his brother at 4755 North Camac Street in Philadelphia while working in a box factory.

Stamm’s older sister, Ilse, also escaped from Germany. In a statement for Yad Vashem dated December 30, 1996, Fred L. Stamm wrote that she was “a children’s nurse [who] accompanied a children’s transport to England.” The Kindertransport was established after Kristallnacht in late 1938 and provided Jewish children—but not their parents—with refuge from the Nazis.

Stamm’s youngest sister, Edith, refused to leave Germany. Fred Stamm wrote that “Despite her younger years, she always worried about her whole family.” Even after Fred Stamm decided to emigrate to the United States, “Edith declared that she was not going to leave her aged mother alone, she was not going to leave her, come what may.”

Fred Stamm later recalled that in February 1939,

When I left for the U.S. my mother and sister accompanied me to the train in Warburg. From the train window I looked down upon my wonderful mother, my beautiful younger sister with the dreadful thought, that I might never see this [close-knit] family again.

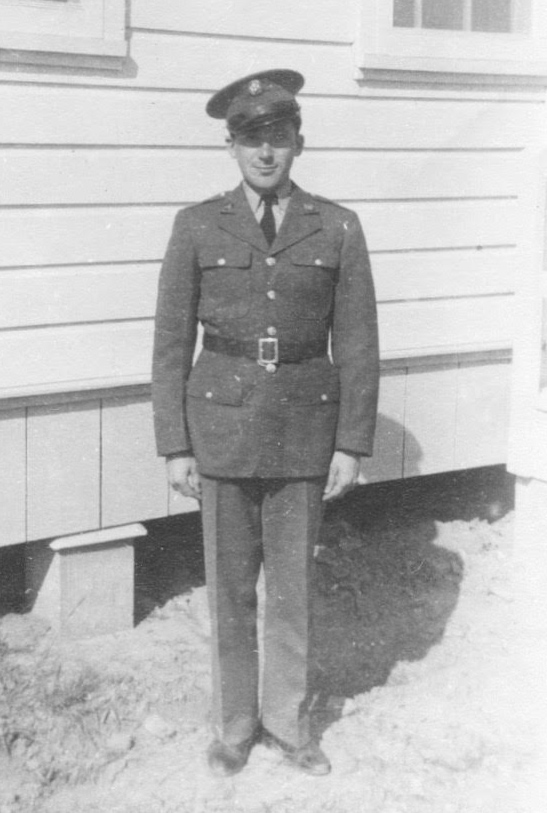

When Stamm registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, he was still living at the North Camac Street address with his brother, Fred, and working for the Seaboard Container Corporation. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, seven inches tall and weighing 132 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. He wore eyeglasses. An annotation to his draft card, dated February 28, 1941, stated that Stamm had moved to 804 North Jefferson St in Wilmington, Delaware. He moved again to 707 North Van Buren Street, also in Wilmington, prior to entering the service.

According to his enlistment data card, Stamm was a high school graduate who worked as a surveyor.

Stateside Training & Iceland

Stamm was drafted before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although he moved to Delaware after registering for the draft, it was a Philadelphia draft board that selected him. Stamm was inducted into the U.S. Army on July 9, 1941. Five days later, on July 14, 1941, he joined Company “D,” 2nd Engineer Training Battalion, 2nd Engineer Training Group, Engineer Replacement Training Center, Fort Belvoir, Virginia. After completing basic training, he transferred out of that unit on September 15, 1941. His movements for the next month are unclear, but Private Stamm joined the 75th Engineer Company (Light Ponton) at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana, on October 17, 1941. This unit constructed temporary floating bridges over bodies of water like rivers.

The following month, Stamm was honorably discharged so that he could volunteer for a one-year term in the Regular Army, enlisting on November 25, 1941. His enlistment data card stated he reenlisted at Fort Lauderdale, Florida, while his last pay voucher stated that he enlisted at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana. The reason that the Army offered this arrangement appears to be related to limits on where draftees could be deployed overseas under the law. (See the Notes section for further details.)

After his reenlistment, Private Stamm transferred to the 394th Engineer Company (Depot), joining that unit at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, at 1100 hours on November 27, 1941. The company, which had the role of operating a supply depot for other Corps of Engineer units, had begun preparations to go overseas that same month. A December 1941 company roster listed his duty and military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code as 186, receiving or shipping checker.

On December 4, 1941, the 394th Engineer Company moved by train to Fort Slocum, New York. When Pearl Harbor was attacked three days later, Stamm and his unit were still staging prior to going overseas. They moved to the New York Port of Embarkation on the morning of December 12, 1941, shipping out the same day for Reykjavík, Iceland, aboard the transport U.S.S. Harry Lee (AP-17).

Although Iceland was neutral in World War II, in May 1940 the British had invaded and occupied the island for strategic reasons. Even before the U.S. entry into World War II, American troops began to relieve the British so the garrison could be put to better use elsewhere.

Two days into the voyage, during a storm, Harry Lee developed engine trouble. On December 15, 1941, she entered port at Halifax, Nova Scotia. On December 20, the ship departed Halifax to return to the United States for repairs, arriving at Boston, Massachusetts, two days later. On December 24, the 394th disembarked and boarded another transport, U.S.S. Heywood (AP-12). However, three days after that they disembarked that ship too and returned to Fort Slocum by rail.

On January 14, 1942, the same day Stamm boarded another transport, U.S.S. Munargo (AP-20), at the New York Port of Embarkation, his father died in Germany. Two months later, on March 28, 1942, Stamm’s mother and sister were arrested by the Nazis and deported to Poland.

The 394th Engineer Company shipped out on January 15, 1942, arriving in Reykjavík 10 days later. They moved to Camp Montezuma, Iceland, where they operated a supply depot. Unit morning reports lists the engineer depot as Camp Belvoir, Iceland, beginning February 5, 1942, but does not make clear whether the unit moved or the base was renamed. (If Camp Montezuma had been a Marine Corps base, it may have been renamed after they departed. Camp Belvoir, located near Reykjavík, was named after Fort Belvoir in the U.S.)

Service in Iceland had its ups and downs. In a letter to his brother, Stamm described Iceland succinctly as “the land of the midnight sun, Mojacks [G.I. slang for Icelandic people], fishheads, mutton and codfish.” Winters were bitterly cold and dark. Soldiers stationed in the Reykjavík area at least had better infrastructure and opportunities for recreation than those stationed in the rest of the country. Camps were largely composed of prefabricated Nissen huts. An Iceland Base Command history report stated:

Life in a low, round “half can” as the huts were sometimes described was not easy. Much of the time the wind was blowing and the sounds assumed fantastic proportions inside these curious structures. During much of the time it was not possible to venture out of the hut except fully clothed in a parka with hood up.

Despite the harsh conditions, there was little threat from the enemy, though German aircraft operating out of occupied Norway were sometimes intercepted above the island and the enemy attempted to land agents by submarine on several occasions.

The 394th remained at Camp Belvoir until at least September 1942. The company’s morning reports from September and October 1942 went missing before they could be microfilmed, though they reveal that the main body of the unit had moved to Camp Hounslow by the beginning of November 1942. The Iceland Base Command report stated:

Three depots were operated by the Engineers: the Belvoir Depot, the Hounslow Depot, and the Keflavik Depot. The Belvoir was operated by the 394th Engineer Depot Company which moved from Camp Belvoir to Hounslow using the Depot at Belvoir as a sub-depot.

The July 1942 roster recorded a change in Stamm’s duty (though not M.O.S.) to 252, foreman warehouse (parts and supplies). The September 1942 roster, the last to record duty and M.O.S., listed a promotion to private 1st class.

During his service overseas, Stamm wrote letters to his brother with impeccable handwriting and in better English than many native speakers. In a V-mail dated December 17, 1942, he that he and his fellow soldiers had a jam session in their quarters playing on a violin, a banjo, a guitar, and a harmonica, adding: “It lasted well over four hours and I don’t think I’ll ever forget times like these.”

While Stamm was serving in Iceland, he was powerless to intervene when he learned that his mother and younger sister, Edith, had been deported to Nazi-occupied Poland. In a statement for Yad Vashem more than half a century later, Fred L. Stamm wrote:

They were taken to the Warsaw Ghetto, from where I received a Red Cross postal card from my mother, asking to send food. This postal card was received by me sometime past December 7TH, 1942 [sic], when the U.S. was already at war with Germany, and all avenues were closed[.]

On November 30, 1942, Fred Stamm, who by then was a member of the Army Air Forces, relayed the worrying message to his brother. In the V-mail dated December 17, 1942, Private 1st Class Stamm replied:

I don’t know what to write about the news you gave me from our beloved mother and Edith. There are no words to describe my feelings, all I can say is: Lets pray to God that he will protect them until we come and liberate them. Some day somebody is going to pay for all that and lets hope that you and I will be there.

The ultimate fates of Alwine and Edith Stamm are lost to history. If they survived starvation in the Warsaw Ghetto, they may have been murdered at the Treblinka death camp in 1942, during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in early 1943, or in the camps where the Nazis sent the survivors of the ghetto.

On January 6, 1943, Stamm wrote:

Tonight after duty hours I went to the movies and saw “This gun for hire,” which was not so good but still it was interesting enough to pass some time away. When I came out I heard several shouts and saw a lot of smoke a little bit up the road. Like a dope I ran there and it was a hut on fire. The same minute I got there some officer grab[b]ed me and put me on the bucket brigade. So I had something to do for a while. It was a good fire and burned like hell even though we saved a lot of the fellows stuff. After a short time we had everything well under control but the smoke was still going strong. After a while I put my bucket down and took off for the simple reason that my clothes were wet and it is pretty damned cold tonight. The redhot stove sure comes in handy tonight and I am sitting almost on top of it now but I don’t seem to be able to get warm. Your bones get so cold and stiff that sometimes you think that you’ll never get warm.

A week later, on January 13, 1943, Stamm wrote about being on kitchen patrol:

It[’]s my turn on K.P. this week and started [M]onday morning at six thirty. The work isn’t so hard but steady till 630 or 7 at night. Don’t think that I have done anything [to get it as a punishment,] it’s just that they[’re] up to my name on the roster and so whether I like it or not, I got it and I must say, I don’t like it a damned bit. The only thing good about it, is that I can eat as much as I want to. I’ll sure be glad when it’s over. […]

I got a few hours off because I worked fast and the mess sergeant couldn’t find any more work. Believe me, that doesn’t happen very often.

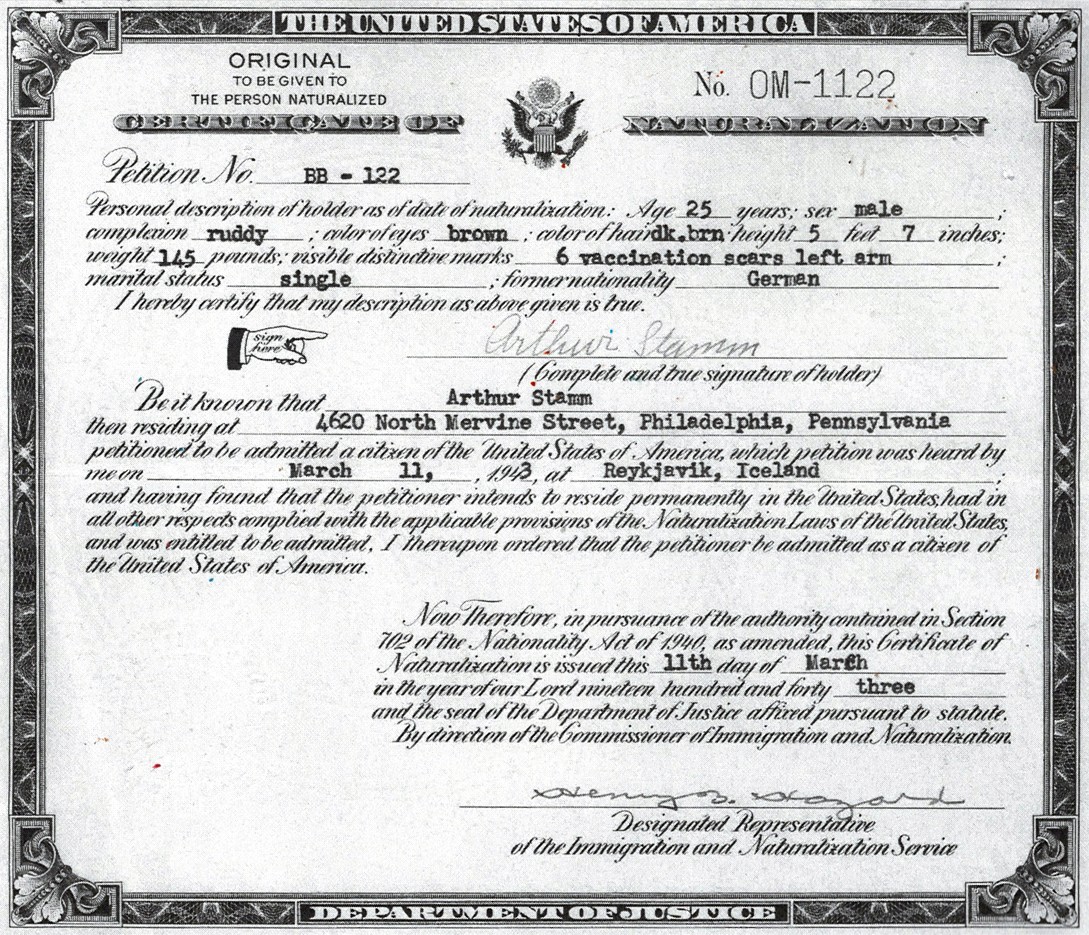

On March 11, 1943, Stamm attended a naturalization hearing in Reykjavík and became a U.S. citizen. He was promoted to technician 5th grade on June 14, 1943.

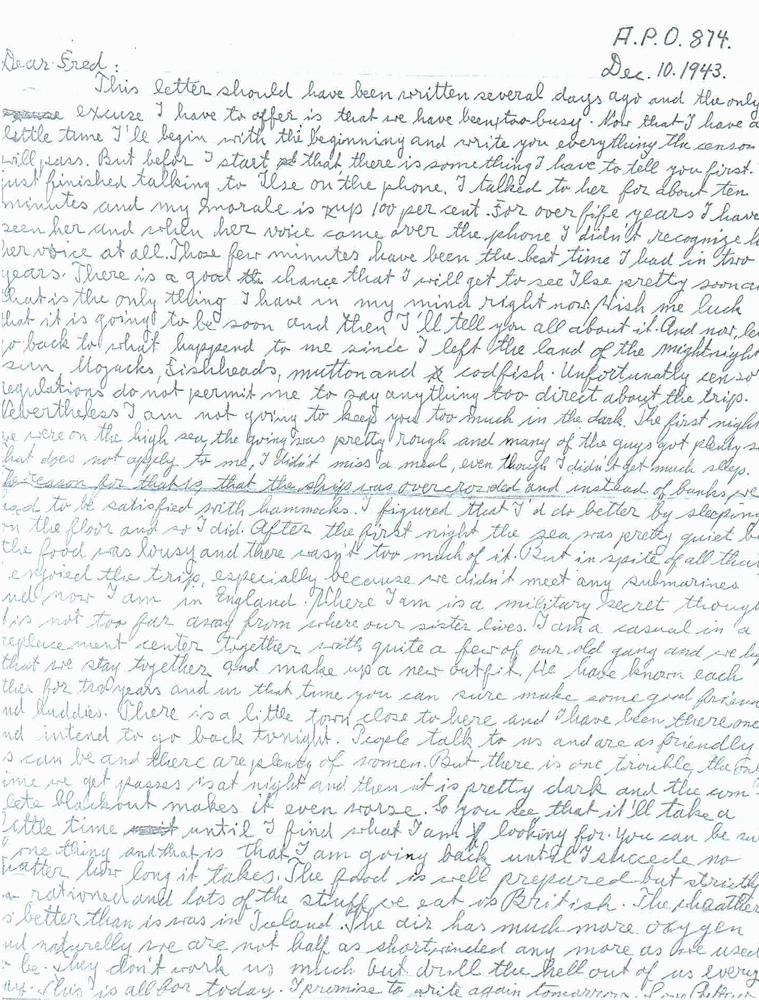

Although Iceland was not really a combat zone, strict censorship was in place and until August 1943 soldiers there were forbidden from disclosing to their families back home that they were stationed on the island. Personal cameras and photography were likewise forbidden until well into the war. On November 19, 1943, Stamm wrote to his brother:

The [weather] is lousy, the pictures in the movies stink but believe it or not, the other day, I got my camera back. That is the first time I had the damn ’thing since we left Slocum and now I am able to buy [some] film but there is never any sunshine so what’s the use taking pictures. I am sending you a few poems in this letter, maybe you know them and maybe you don’t but please do me a favor and save them because I haven’t any copies of them left. Tomorrow night the whole company is going to have a big blowout with lots of beer and plenty of steak and yours truly will most probably be drunk before the night is over.

Stamm closed the letter by adding that he was “wishing you the best of luck and may God bless you and be with you and protect you, wherever you are. Lots of love from your brother[.]”

Though Stamm did not disclose the reason for the party, it may have been because the men in the unit would soon be parting ways. In the fall of 1943, large numbers of men transferred out of the 394th Engineer Depot Company prior to its deactivation on December 17, 1943. Curiously, although Technician 5th Grade Stamm was listed as being dropped from the company payroll in December 1943, the return address on a letter to his family dated November 24, 1943, indicated that he was already with a casual detachment in Iceland.

Soon after, Stamm boarded a transport. He later wrote to his brother that he avoided the seasickness that afflicted many of the other soldiers on board, adding:

I didn’t miss a meal, even though I didn’t get much sleep. The reason for that is, that the ship was overcrowded and instead of bunks, we had to be satisfied with hammocks. I figured that I’d do better by sleeping on the floor and so I did. After the first night the sea was pretty quiet but the food was lousy and there wasn’t too much of it.

Service in the United Kingdom

On December 5, 1943, Technician 5th Grade Stamm was attached unassigned to the Casual Detachment, 10th Replacement Depot, in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England. The move from Iceland to England presented Stamm with the opportunity to speak with his sister, Ilse, who had escaped to the United Kingdom. He wrote to his brother on December 10, 1943:

I just finished talking to Ilse on the phone. I talked to her for about ten minutes and my morale is up 100 per cent. For over fi[v]e years I haven’t seen her and when her voice came over the phone I didn’t recognize her […] voice at all. Those few minutes have been the best time I had in two years. There is a good chance that I will get to see Ilse pretty soon. That is the only thing I have in my mind right now.

It is unclear if Stamm was ever able to see his sister again in person. She survived the war in the U.K. and immigrated to the United States in 1947.

In his letter, Stamm added that many former members of the 394th Engineer Company were in the same replacement unit and expressed hope “that we stay together and make up a new outfit. We have known each other for two years and in that time you can sure make some good friend and buddies.”

By December 13, 1943, Stamm was stationed in or near Lichfield with Company “C,” 49th Replacement Battalion. In a letter to his brother dated December 15, 1943, Stamm wrote:

This is the first place I have seen where two years service in Iceland give a man some kind of privilege. We have priority on all six hour passes, are the only ones who are eligible to get twel[v]e and twenty four hour passes and believe me, we really take advantage of that.

He also noted they were excused from some training that new arrivals had to attend. One other thing he noticed about being stationed in England was that

the chow is comparatively good and we get enough to eat. The bread is just like the one we used to eat back home in the old country. I can’t say that I like it too much thought it is supposed to have more vitamins than our American bread. I just found out that I am on K.P. tomorrow, that will be the first one in almost a year[.]

On December 18, 1943, a set of orders came down dispatching Stamm and a group of enlisted men to General Depot G-25 in Ashchurch, Gloucestershire, on or about December 20, 1943. His M.O.S. code was listed as 324, stock clerk.

On December 18, 1943, orders came down detaching Stamm from Company “C,” 49th Replacement Battalion, 10th Replacement Depot, effective on or about December 20, 1943. Extant documentation is unclear but it appears that upon arrival at G-25, he was further attached to the 463rd Engineer Base Depot Company there. That suggests he was serving with a unit similar to his unit in Iceland.

On March 31, 1944, Technician 5th Grade Stamm went on detached service to U.S. General Depot G-45 in Thatcham, Berkshire, England, until April 12, 1944, when he was among a group of 12 enlisted men detached from that unit and attached back to the 463rd Engineer Base Depot Company. He arrived on April 13, 1944, but he was not there for long. The following day, Stamm was transferred to General Depot G-24 in Honeybourne, Worcestershire, England, where he was attached to the Engineer Casual Detachment. (Confusingly, later records refer to the detachment in Honeyborne as the 463rd Engineer Base Depot Company (Casual Detachment), although the main body of the 463rd remained in Ashchurch.)

In England, Technician 5th Grade Stamm had a relationship with a local woman. During the summer of 1944, she became pregnant with twins that Stamm never met. It is unclear if Stamm ever learned that he was going to be a father.

Stamm remained with the 463rd Engineer Base Company (Casual Detachment) until August 16, 1944, when he was transferred by orders of Headquarters Southern Base Section and reentered the U.S. Army’s complex replacement system.

On August 18, 1944, Technician 5th Grade Stamm was attached unassigned to the 494th Replacement Company, 103rd Replacement Battalion, 11th Replacement Depot, stationed east of Chester, Cheshire. Then, on September 1, 1944, he was transferred to the 12th Replacement Depot and assigned to Detachment 54 at Tidworth Barracks, Wiltshire.

Most replacements found the replacement depots—or repple depples as the soldiers called them—extremely unpleasant. In his book, Beyond the Beachhead, historian Joseph Balkoski explained:

Replacements were the army’s homeless. After a hasty separation from the units with which they had trained or fought, the lonely replacements found themselves in an unfamiliar repple depple, where they lost all sense of belonging to a cohesive military unit. Even new friendships made within the replacement depots were generally fleeting since it was unlikely that two buddies would be assigned to the same squad, or even the same platoon. Many replacements thought of themselves as nameless pieces of army equipment, like crates of ammunition, sent to the front and promptly consumed. […] “Being a replacement is just like being an orphan,” a rifleman recalled.

On September 23, 1944, Stamm and Technician 5th Grade Edgar M. Rosenthal (1918–2002) were reported absent without leave (A.W.O.L.) from Tidworth Barracks. The two men had joined the 394th Engineer Company on the same day in 1941 and served together for years. They turned themselves in October 5, 1944, and were confined to quarters pending court-martial.

According to payroll records, after conviction in a court-martial on October 12, Stamm was reduced to the grade of private and sentenced to forfeit $20 of his monthly pay for five months. Curiously, he was carried as a technician 5th grade on all known morning reports for the rest of his military career, including those from the unit in which he was court-martialed.

The U.S. Army faced a severe manpower shortage during the fall of 1944. Casualties in the European and Mediterranean Theaters, especially in rifle companies, were higher than anticipated and outstripped the rate of conscription and training in the United States. As a result, the Army searched for able-bodied men, especially those already overseas in rear echelon units, and gave them brief retraining as infantrymen. Stamm and Rosenthal were among those men selected for transfer and their branch changed from Corps of Engineers to Infantry.

Stamm and Rosenthal were released from arrest in quarters on November 1, 1944. That same day, they were attached to Replacement Detachment X 125F (also known as Reinforcement Company X125-F) and dispatched to the continent. Transfer Order No. 125 noted that all enlisted men in the detachment including Stamm were trained as riflemen, M.O.S. 745. Headquarters 12th Replacement Depot wanted to get the men to the front and into combat as soon as possible, going so far as to specify: “These orders do not authorize visits for any purpose whatsoever to Paris.”

Combat in the European Theater

Morning reports indicate that Private Stamm’s group was briefly attached to the 14th Replacement Depot near Neufchâteau, France. Stamm and the others were then attached to the 53rd Replacement Battalion at Conflans-en-Jarnisy, west of Metz, France. From there, they were transferred to combat units, with Stamm in a group dispatched to join the 90th Infantry Division on November 19, 1944. That same day, Private Stamm joined Company “E,” 358th Infantry Regiment, 90th Infantry Division, which was out of the line at Metzeresche, France.

The 358th Infantry, under the command of Colonel Christian Hudgins Clarke, Jr. (1905–1995), was recuperating after the Battle of Metz but on alert to be ready to move within three hours of receiving orders. The following day, November 20, 1944, was another rest day, albeit with the regiment now on standby to move in an hour. For the unit’s veterans, time away from the front was an opportunity to clean equipment, eat hot meals, and rest before the next push. For replacements like Stamm, it was their only opportunity to acclimate to their new unit and get to know their squadmates before going into combat for the first time. As he waited to move out, Stamm may have reflected on what he had told his brother in 1942. Now, nearly two years later, it was already too late to save his mother and younger sister, but as a member of the Allied forces driving into Germany, his other wish—to be there when the Nazis paid for what they had done—had been granted.

At noon on November 21, 1944, the 358th Infantry began moving back to the front, with Stamm’s 2nd Battalion heading east to Sierck-les-Bains, France, near where the borders of France, Luxembourg, and Germany meet. The regiment’s officers began planning and reconnaissance for their next mission. In cooperation with Combat Command “A,” 10th Armored Division, the 358th Infantry would pierce the German frontier defenses, including belts of antitank barricades known as dragon’s teeth and numerous pillboxes.

November 23, 1944, was surely a bittersweet day for Stamm. In addition to being Thanksgiving Day for the Americans, it was also the day Stamm returned to his homeland after nearly six years away. The 358th Infantry crossed the German border near Perl, Saarland. According to the regimental after action report, 2nd Battalion “assembled in the woods to the east of BORG, prepared to attack towards the North[.]”

The upcoming assault followed the standard American doctrine of “two up, one back.” 2nd and 3rd Battalions would spearhead the attack while 1st Battalion remained in reserve. Within 2nd Battalion, Stamm’s Company “E” along with Company “F” would attack, while Company “G” remained in reserve. The attack got off to an inauspicious start around 1130 hours when tanks from the 10th Armored Division accidentally shelled 2nd Battalion. That delayed the assault until 1400 hours. Private Stamm and Company “E” advanced about 1,000 yards, reaching the dragon’s teeth. They dug foxholes for the night. Despite the close call from friendly fire and the cold, wet weather, the company morning report recorded morale as good.

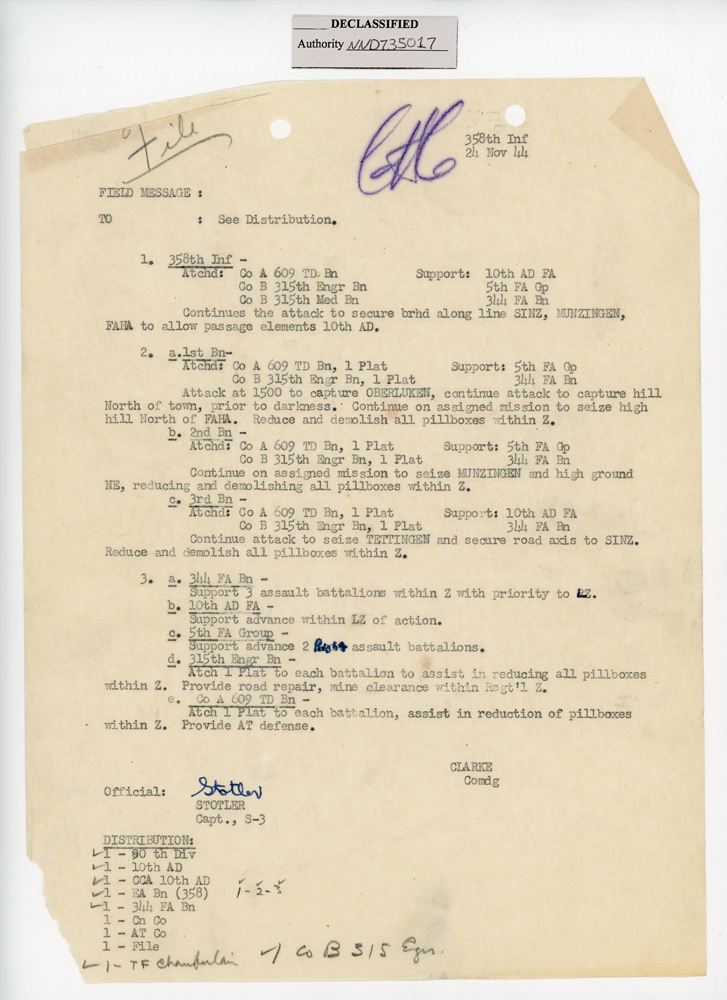

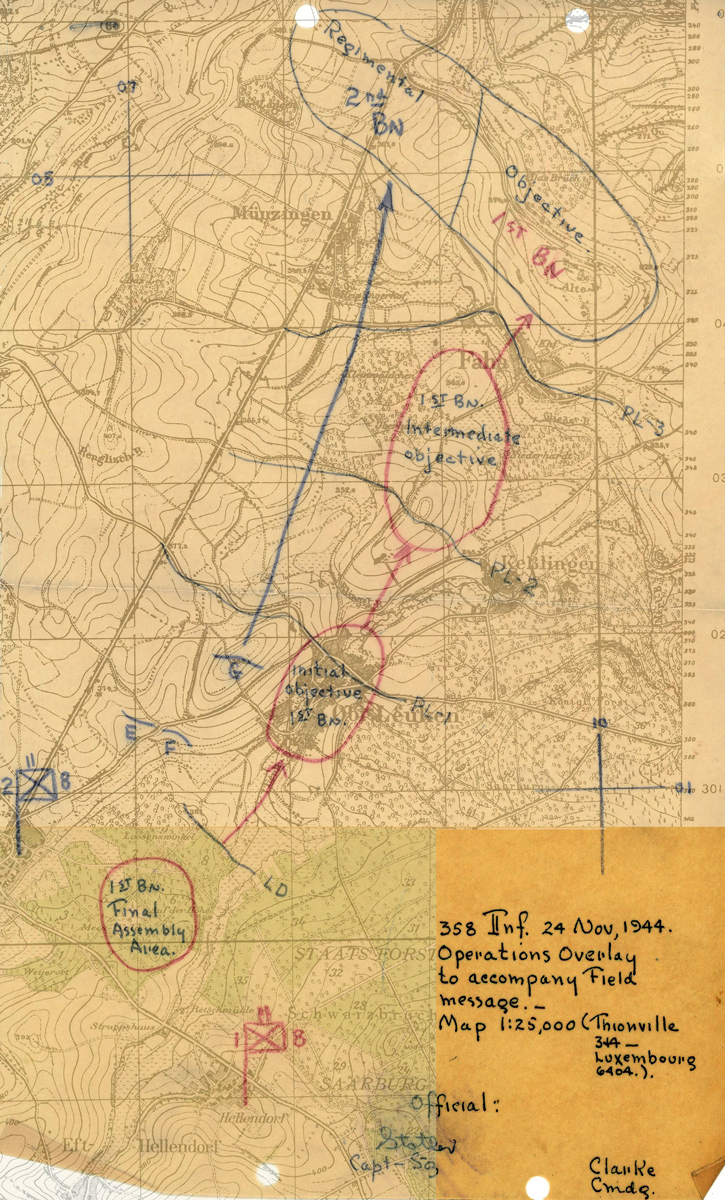

The following day, November 24, 1944, was the sixth anniversary of Stamm’s escape from Germany. Colonel Clarke’s orders were for the 358th Infantry to continue “the attack to secure brhd [bridgehead] along line SINZ, MUNZINGEN, FAHA to allow passage elements 10th AD [Armored Division].” Stamm’s 2nd Battalion, with a platoon of tank destroyers and another of combat engineers attached, was ordered to advance to the northeast to capture Münzingen and the high ground beyond while destroying enemy pillboxes located in the area. The battalion jumped off in the attack against Hill 388 at 0630 hours.

The 90th Infantry Division after action report stated that 2nd Battalion’s attack was “slowed by heavy direct fire from the N[orth] and more particularly by enfilading machine gun fire from a huge pillbox on the outskirts of OBERLEUKEN.” Although a team neutralized that pillbox, “the attack on the hill continued to make little progress as the German[s] tenaciously defended this excellent approach down the hogback ridge to SAARBURG.”

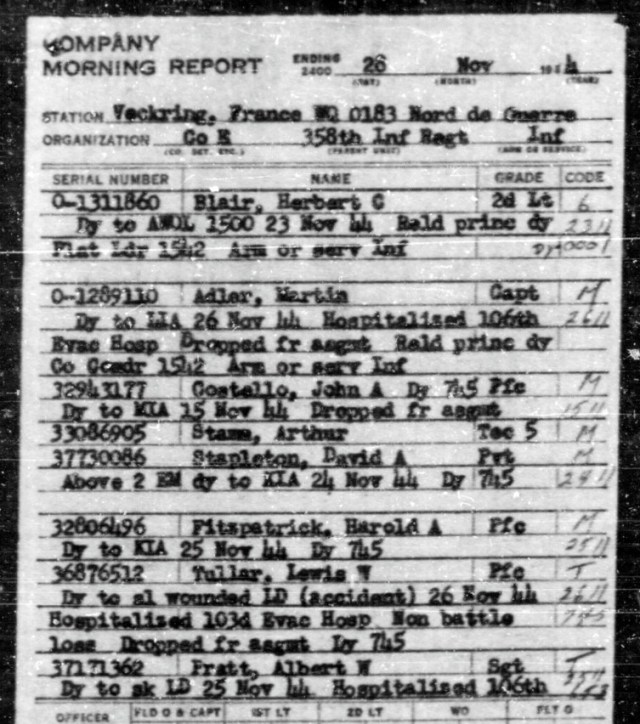

The Company “E” morning report that day recorded that weather was again “cold and rainy” and the company was “held up by heavy artillery and mortar fire” and unable to advance. Company morale deteriorated and was rated as poor.

During combat that day, November 24, 1944, Stamm was reported as killed in action. According to his burial report, he was fatally struck in the head by artillery shell fragments. He was initially buried at the U.S. Military Cemetery Limey, France, on November 29, 1944.

Stamm’s personal effects included a wallet, two pen knives, a souvenir buckle, and some British and French currency. Dr. Camille J. Stamm inquired about a gold Elgin watch that he had given Stamm, but there is no indication that it was ever found.

Corporal Fred L. Stamm, an airplane and engine mechanic, had been in transit to the China Burma India Theater when his brother was killed. On December 30, 1944, he joined the 16th Fighter Squadron, 51st Fighter Group at Chengkung Airfield, China. A few weeks later, the news reached him. In a letter to his brother’s company commander dated January 23, 1945, Corporal Stamm wrote:

A few days ago I received a telegram saying that my brother Arthur Stamm ASN 33086905 has been killed in action on November 24 in Germany. My brother was a member of your company and I hope that you can give me some information about his death.

It has hurt me bitterly to hear that he had been killed in action. We were both refugees from Germany, escaped from there in 1939. I have now lost my whole family in this war and don’t even know where any of them is buried. Please tell me whether a jewish [sic] chaplain was present when he was buried. Do any of your men know how his death occur[r]ed? Did he have to suffer much? What became of his personal belongings? Where is he buried?

The letter was forwarded to the Adjutant General’s Office, which responded on May 15, 1945, in the name of Major General James Alexander Ulio (1882–1958):

I wish to advise you that an additional report has been received in the War Department. This report states that the company, of which Private Stamm was a member, was participating in an attack on a town in the vicinity of Borg, Germany. Strong enemy resistance was encountered. Your brother, and other members of the organization, succeeded in capturing fourteen pillboxes and cleared several tank traps. Due to continuous artillery fire, Private Stamm and his company were obliged to move to more advantageous positions. It was during this action that your brother was instantly killed as a result of a shell fragment.

The Office of the Quartermaster General sent a letter to Louis Stamm in February 1948 requesting he fill out disposition paperwork, but the letter came back with a sticker attached that the recipient was deceased.

Army policy determined a soldier’s next of kin in a specific order of precedence. Decisions regarding an unmarried soldier with no children over 21 would ordinarily fall to the soldier’s father and if he was deceased, to the mother. This was complicated by the fact that Louis Stamm had died in Germany during the war. Obtaining documentation of his father’s death was one thing, but the fact that his mother had been deported and presumably killed during the Holocaust was difficult for Fred Stamm to prove.

In a letter dated April 18, 1948, Fred Stamm wrote to the Quartermaster General that he was working to obtain necessary documentation about the fate of his parents, adding:

I beg you sir, not to move the remains of my brother until this matter has been cleared. It is definitely my wish and it shall be my right to request that the remains of my late brother should be transferred for final burial in Philadelphia Pa.

Around June 1948, Fred Stamm was able to provide documentation that his father had died in Warburg on January 14, 1942. Local authorities in Warburg also certified that Stamm’s mother and younger sister were arrested on March 28, 1942, and taken by locked transport to Warsaw, Poland. U.S. authorities accepted this evidence as sufficient to establish Fred Stamm as his brother’s legal next of kin.

In June 1948, Stamm’s casket was moved to another military cemetery, at Saint-Avold, France. That same summer, Fred L. Stamm made the formal request that his brother’s body be repatriated to the United States. Finally, in early 1949, his body returned from Antwerp, Belgium, to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the Liberty ship Barney Kirschbaum.

A military escort accompanied the casket via train from Penn Station in New York City to Philadelphia on the afternoon of April 11, 1949. Following services on April 17, 1949, Stamm was buried at Montefiore Cemetery in Abington Township, Pennsylvania, northeast of Philadelphia. Even though he entered the service from Delaware, Stamm’s name was not included at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

In April 1945, the British woman who Stamm had a relationship with gave birth to twin boys. One of the children died shortly after birth. Stamm’s surviving son, named Bill, was raised Catholic by his maternal grandmother in Birmingham, England. He knew that his father was an American soldier but Bill’s family never told him his father’s name. In recent years, he finally learned his father’s identity through D.N.A. testing. Although too late to meet anyone in the Stamm family who knew his father, he was able to meet Fred Stamm’s daughter, Jennifer Abraham, who gave him a pair of Private Stamm’s eyeglasses as a memento.

Notes

First Name

Stamm’s first name may have originally been Artur, a more common spelling in German than Arthur. In his 1939 declaration of intention to become an American citizen, Stamm stated that he immigrated under the name Artur Stamm. However, his Warburg registration card, 1938 passport and the S.S. Hamburg passenger manifest all list his name as Arthur Stamm.

Address in Germany

This article originally stated incorrectly that the Stamm family had lived in the Daseburg district of Warburg. In the present day, Daseburg has a Mittelstraße. However, the prewar Mittelstraße in downtown Warburg, where the Stamms lived, was renamed Josef-Wirmer-Straße after the war in honor of local anti-Nazi Josef Wirmer (1901–1944) who was executed in the aftermath of the attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944.

Naturalization

According to his enlistment data card, Stamm was a citizen when he was drafted in 1941. However, the naturalization certification retained in U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services records shows him being naturalized during his military service in 1943. The enlistment data card might have had an error made at the time or when it was later digitized, or there could have been confusion over the fact that he was in the process of naturalization when he was drafted.

Iceland Deployment

With the Service Extension Act of 1941, the military could have retained Stamm for longer than a year rather than discharging him in November 1941 and reenlisting him into the Regular Army. Since quite a few other members of his future unit were natural born citizens who had been drafted and then within months gone into the Regular Army just like Stamm, it would not seem to have anything to do with him being foreign born nor did it appear to have accelerated his naturalization process. The most likely explanation is that in the Regular Army he would be immediately deployable overseas. This is supported by the fact that after reenlisting he was immediately transferred to a unit that was preparing to ship out to Iceland.

By law, before the attack on Pearl Harbor, American draftees could not be deployed outside the Western Hemisphere except to U.S. territories like the Philippine Islands. However, going back as far as the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, no declaration nor law defined the boundaries of the Western Hemisphere, though it was generally understood to cover the Americas (New World). Contemporary newspaper and magazine articles from 1940 and 1941 show that there was no consideration of using the Greenwich meridian to define the Western Hemisphere. The most common definition used the 20th meridian west of Greenwich, but that would have included only western Iceland. A July 21, 1941, article in Time magazine noted that the issue came up again after President Roosevelt announced that the U.S. Marine Corps had been deployed to Iceland:

At his press conference next afternoon President Roosevelt smilingly turned aside a question about his definition of the Western Hemisphere. It all depended, said he, on what geographer he had consulted last. A newsman reminded him that once he had marked the border of the Western Hemisphere as a line running between Greenland and Iceland. The President chuckled: it all depended on what geographer he had consulted last.

A 1970 history of the U.S. Marine Corps in Iceland makes it clear that the entire reason that a Marine brigade was deployed to Iceland at all instead of the U.S. Army was that the Regular Army was spread thin providing cadres to train new units of draftees who “could not be sent beyond the Western Hemisphere unless they volunteered for such service.” It added: “Since all Marines, both regular and reserve, were volunteers, there were no geographical restrictions on their use.” However, the Army was still expected to take over the mission as soon as possible.

Thus, it appears that the Army understood Iceland to be excluded from the Western Hemisphere by the spirit if not the letter of the law and endeavored to expand the ranks of the Regular Army to comply with its mission to take over occupation of the island. Ironically, it would become a moot point shortly after Stamm’s reenlistment, since following Pearl Harbor draftees were sent to war zones all over the globe. The shorter one-year term of enlistment in the Regular Army which Stamm accepted also became moot as both draftees and regulars were retained in the service for the duration of hostilities.

394th Engineer Company

Various sources give slightly different designations for one of Stamm’s early units: 394th Engineer Company, 394th Engineer Depot Company, and 394th Engineer Company (Depot). It is unclear if the unit was redesignated several times or whether these were all just variations.

Rosenthal

Stamm’s buddy, Edgar M. Rosenthal joined the 358th Infantry Regiment on the same day as Stamm, albeit as a member of Company “A.” He was wounded in action on December 10, 1944, and spent months recovering before being discharged from both the hospital and the military.

War Department Letter

The letter to Corporal Fred L. Stamm was written in the name of Major General James A. Ulio. Almost certainly, it was written by his staff, since millions of telegrams and letters to families of casualties were written in his name during the war.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Private Stamm’s niece, Jennifer Abraham, for providing photos, letters, and information that were vital in telling this story. Thanks also go out to Dr. Alexander Schwerdtfeger-Klaus, director of the Museum im “Stern” and Stadtarchiv Warburg, and to Ruth Kröger-Bierhoff for contributing photos, documents, and information.

Bibliography

Abraham, Jennifer. Telephone interview on January 11, 2023, and email correspondence on January 16, 2023.

Application for Headstone or Marker for Arthur Stamm. April 17, 1949. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/550581257?objectPage=2404

Balkoski, Joseph. Beyond the Beachhead: The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2005.

Beatty, Morgan M. “Where Is This Western Hemisphere Anyway, When Many Folks Disagree?” The New London Evening Day, September 30, 1941. https://www.newspapers.com/article/182247323/

Certificate of Naturalization for Arthur Stamm. March 11, 1943. Certificate Files, September 27, 1906 – March 31, 1956. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Clarke, Christian H. Jr. “Field Message.” November 24, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Declaration of Intention for Citizenship for Arthur Stamm. October 19, 1939. Declarations of Intention for Citizenship, 1901–1979. Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States. National Archives at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2717/images/47295_302022005448_1597-00674

Declaration of Intention for Citizenship for Fritz Stamm. September 12, 1939. Declarations of Intention for Citizenship, 1901–1979. Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States. National Archives at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2717/images/47295_302022005448_1596-00740

“Detachment, 394th Engineer Depot Company.” May 9, 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/432768223?objectPage=652

Draft Registration Card for Arthur Stamm. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Pennsylvania, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSW5-4QD8-L

Enlistment Record for Arthur Stamm. November 25, 1941. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=33086905&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3575876

Enlistment Record for Fred L. Stamm. July 29, 1942. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=33324948&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3803996

“Final Roster 394th Engr Depot Co.” December 17, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002_20.pdf

“Final Statement of Arthur (nmi) Stamm 33086905 Private Co ‘E’ 358th Inf.” December 16, 1944. Individual Pay Vouchers, c. 1926–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Jennifer Abraham.

Hospital Admission Card for 32092337. December 1944. U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/704694633/rosenthal-edgar-m-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

Hospital Admission Card for 33086905. November 1944. U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/704984880/stamm-arthur-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

“Immigration to the United States 1933–41.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/immigration-to-the-united-states-1933-41

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Arthur Stamm. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

“List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigrant Inspector at Port of Arrival S. S. ‘Hamburg’, Passengers sailing from Hamburg, November 24th, 1938. Arriving at Port of New York, December, 2nd., 1938.” 1938. Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Record Group 36, Records of the U.S. Customs Service. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7488/images/NYT715_6256-0274

“List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigrant Inspector at Port of Arrival S. S. ‘Queen Mary’, Passengers sailing from Southampton, 4th December, 1947 Arriving at Port of New York, 16th December, 1947.” 1947. Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Record Group 36, Records of the U.S. Customs Service. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7488/images/NYT715_7515-0794

“Monthly Personnel Roster Dec 31 1941 394 Eng Co.” December 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002_18.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster July 31 1942 394 Eng Co.” July 31, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002_18.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Oct 31 1941 75th Eng Co–L–P.” October 31, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1001/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1001_03.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Sep 30 1941 Company D 1309SU 2 Eng Tng Bn.” September 30, 1941. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0980/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-0980_08.pdf

“Monthly Personnel Roster Sept 30 1942 394 Eng Co.” September 30, 1942. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002_18.pdf

Morning Reports for 16th Fighter Squadron, 51st Fighter Group. December 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-12/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0610/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0610-18.pdf

Morning Reports for 394th Engineer Company. November 1941 – June 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1161/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1161-14.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1161/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1161-15.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1161/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1161-16.pdf

Morning Reports for 463rd Engineer Base Depot Company. December 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0616/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0616-13.pdf

Morning Reports for 463rd Engineer Base Depot Company. March 1944 – April 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0672/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0672-27.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-04/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0623/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0623-02.pdf

Morning Reports for Casual Detachment, 10th Replacement Depot. December 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0713/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0713-07.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0713/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0713-10.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “A,” 358th Infantry Regiment. November 1944 – December 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0469/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0469-03.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-12/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0399/85713825_1944-12_Roll-0399-27.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “D,” 2nd Engineer Training Battalion, 2nd Engineer Training Group. July 1941 – November 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1144/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1144-20.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “E,” 358th Infantry Regiment. November 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0469/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0469-05.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment 53, Ground Forces Replacement System, 53rd Replacement Battalion. November 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0556/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0556-12.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment 54, Ground Forces Replacement System. September 1944 – November 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-09/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0581/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0581-14.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-10/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0601/85713825_1944-10_Roll-0601-06.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0556/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0556-16.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment 81, Ground Forces Replacement System. November 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0559/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0559-11.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-11/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0559/85713825_1944-11_Roll-0559-12.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment 103, Ground Forces Replacement System. September 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-09/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0487/85713825_1944-09_Roll-0487-06.pdf

Morning Reports for Engineer Section U.S. General Depot G-25. March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0664/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0664-12.pdf

Morning Reports for General Depot G-45. April 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-04/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0615/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0615-22.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-04/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0615/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0615-23.pdf

“Narrative History Iceland Base Command ‘Always Alert’ 16 September 1941 – 31 December 1945.” Undated, c. 1946. https://www.fold3.com/image/291734866/593-iceland-base-command-historical-summary-1941-43-page-3-us-wwii-european-theater-army-records-194

“National Affairs: Lesson in Geography.” Time, July 21, 1941. https://time.com/archive/6765134/national-affairs-lesson-in-geography/

“Part II The Drive to the Saar 24–30 November 1944.” Undated, c. December 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. The 90th Division Association website. https://www.90thdivisionassoc.org/afteractionreports/Scans/nov44/90th%20Div%20AAR%20Nov%2044%20Pgs%2031-41.htm

“Pay Roll of 394th Engineer Depot Company For month of December, 1943.” December 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002_20.pdf

“Pay Roll of 394th Engineer Depot Company For month of July, 1943.” July 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1002_20.pdf

“Pay Roll of 463rd Engr Base Depot Co For month of December, 1943.” December 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1008/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1008_08.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1008/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1008_09.pdf

“Regimental History 358th Infantry.” Undated, c. December 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. The 90th Division Association website. https://www.90thdivisionassoc.org/History/AAR/Regtl/358/358%20AAR%2011%20November%201944.pdf

Stamm, Arthur. Letter to Fred Stamm. December 10, 1943. Courtesy of Jennifer Abraham.

Stamm, Arthur. Letter to Fred Stamm. December 15, 1943. Courtesy of Jennifer Abraham.

Stamm, Arthur. Letter to Fred Stamm. January 6, 1943. Courtesy of Jennifer Abraham.

Stamm, Arthur. Letter to Fred Stamm. January 13, 1943. Courtesy of Jennifer Abraham.

Stamm, Arthur. V-mail to Fred Stamm. December 17, 1942. Courtesy of Jennifer Abraham.

Stamm, Fred L. “Page of Testimony for Alwine Stamm, nee Loeb.” December 30, 1996. Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center website. https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/names/13926049

Stamm, Fred L. “A page of testimony submitted by Fred L. Stamm.” December 30, 1996. Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center website. https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/names/13955671

Stinnett, Jack. “Congress Talks About ‘Western Hemisphere’ But Geographers Don’t Know What It Means.” The Corpus Christi Times, July 2, 1940. https://www.newspapers.com/article/182247718/

“Synagoge An der Burg (Warburg).” Jewish Places website. https://www.jewish-places.de/de/DE-MUS-975919Z/facility/88085762-8835-43b7-8d62-a946ce636c8b

“T/5 Arthur Stamm.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/54081857/arthur-stamm

The United States Marines in Iceland, 1941–1942. Historical Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1970. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/The%20United%20States%20Marines%20in%20Iceland,%201941-1942%20%20PCN%2019000412300.pdf

“Warburg (Kreis Höxter).” Alemannia Judaica website. https://www.alemannia-judaica.de/warburg_friedhof.htm

“War Diary U.S.S. Harry Lee From: December 1, 1941 to December 31, 1941.” Undated, c. 1942. World War II War Diaries, Other Operational Records and Histories, c. January 1, 1942–c. June 1, 1946. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/133982671

War Record for Camille Joseph Stamm. September 18, 1919. World War I Jewish Servicemen Questionnaires, 1918-1921. American Jewish Historical Society. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1765/records/282

Last updated on February 13, 2026

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.