| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Connecticut, Delaware | Accounting clerk |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Marine Corps Reserve | Enlisted 313762 / Officer 08488 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Company “D,” 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Guadalcanal |

Early Life & Family

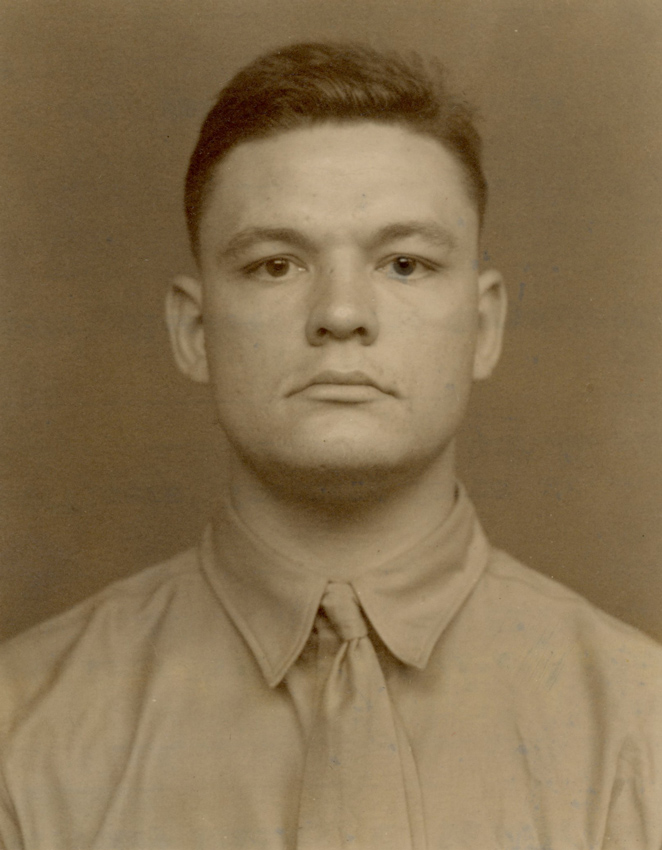

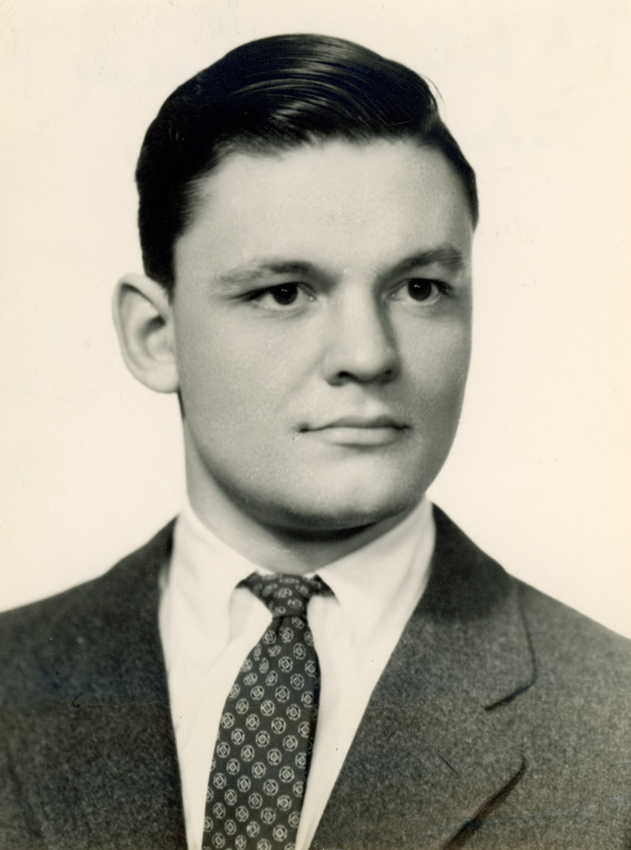

Richard Peter Richards was born at the Stamford Hospital in Stamford, Connecticut, on May 20, 1918. He was the third child of Leonard Richards, Jr. (1886–1946) and Anita Warren Richards (1886–1959). Census records, his personnel file, and his college yearbook indicate that he went by R. Peter Richards, Peter Richards, and Pete Richards. He had two older brothers, Leonard Richards, III (who served in the Army Air Forces during World War II and in the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War, 1910–1959), and Warren Richards (1914–1997, who served in the U.S. Naval Reserve during World War II).

Richards’s father had worked for a family business that was purchased by a Delaware company shortly before his youngest son was born. The elder Richards’s obituary explained:

In 1906 [Leonard] Richards went to work with his father with Richards and Company, manufacturers of lacquer and leather cloth at Stamford, Conn. The Atlas Powder Company acquired the company in July, 1917, and Mr. Richards joined the Atlas staff.

Richards was recorded on the census in January 1920 living on Shippan Avenue in the Shippan Point neighborhood of Stamford with his parents, two older brothers, and the family’s three servants. Evidently, the acquisition of Richards and Company eventually led the family to move to Wilmington, Delaware, where Atlas was headquartered. On December 13, 1923, Richards’s father purchased a property at 2601 West 17th Street, which was to be Richards’s permanent address until he entered the military.

Richards shared a love of horses with his parents. Journal-Every Evening stated that he “was a fine horseman and took part in many local horse shows and also rode in many hunts of the Vicmead” Hunt Club. Journal-Every Evening noted that Richards’s mother “was a horsewoman, well-known among fox hunting and show ring enthusiasts.” Richards’s father was president of the Vicmead Hunt Club, as well as the first chairman of the Delaware Racing Commission from 1935 until his death. For many years, Delaware Park held the Leonard Richards Stakes in his honor, until it was renamed the Barbaro Stakes, after a famous racehorse, in 2007.

Journal-Every Evening reported that Richards “attended Tower Hill School, St. Andrew’s School at Middletown and the Hill School, Pottstown, Pa.” Both St. Andrews and The Hill School were boys’ preparatory boarding schools. The latter school suggested that Richards (or his father) had Princeton University in mind, though Richards ended up attending Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, beginning in September 1937.

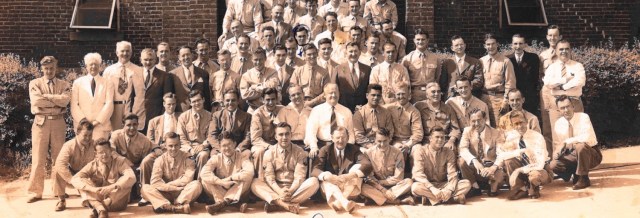

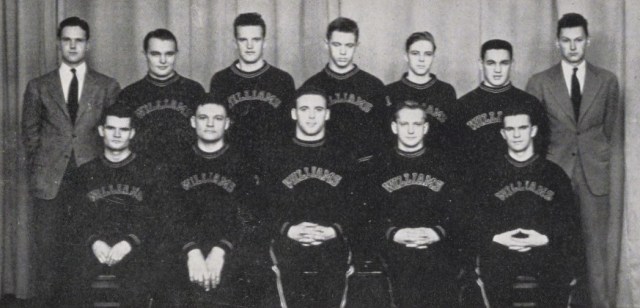

On June 16, 1941, Richards graduated from Williams College with a Bachelor of Arts in History. His extracurricular activities included football as a freshman, four years of wrestling, as well as membership in an honor society at the college known as the Gargoyle Society. In a recommendation letter for Richards dated March 24, 1941, Williams College President James Phinney Baxter, III (1893–1975), wrote:

Mr. Richards entered Williams from The Hill School, Pottstown, Pennsylvania and, though not a brilliant student, has won the respect of the faculty and student body alike. He has taken part in freshman football and varsity track and has been one of the most aggressive and successful of our varsity wrestlers. He was chosen a junior adviser, a position of much responsibility and prestige on this campus, and served during his junior year as chairman of that group. He was also elected last spring a member of our honorary senior society. I think he would make a fine officer.

Richards told the Marine Corps that he had worked in a kitchen at camp and as an accounting clerk.

According to his Marine personnel file, Richards stood five feet, 10 inches tall and weighed 173 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. He was Protestant.

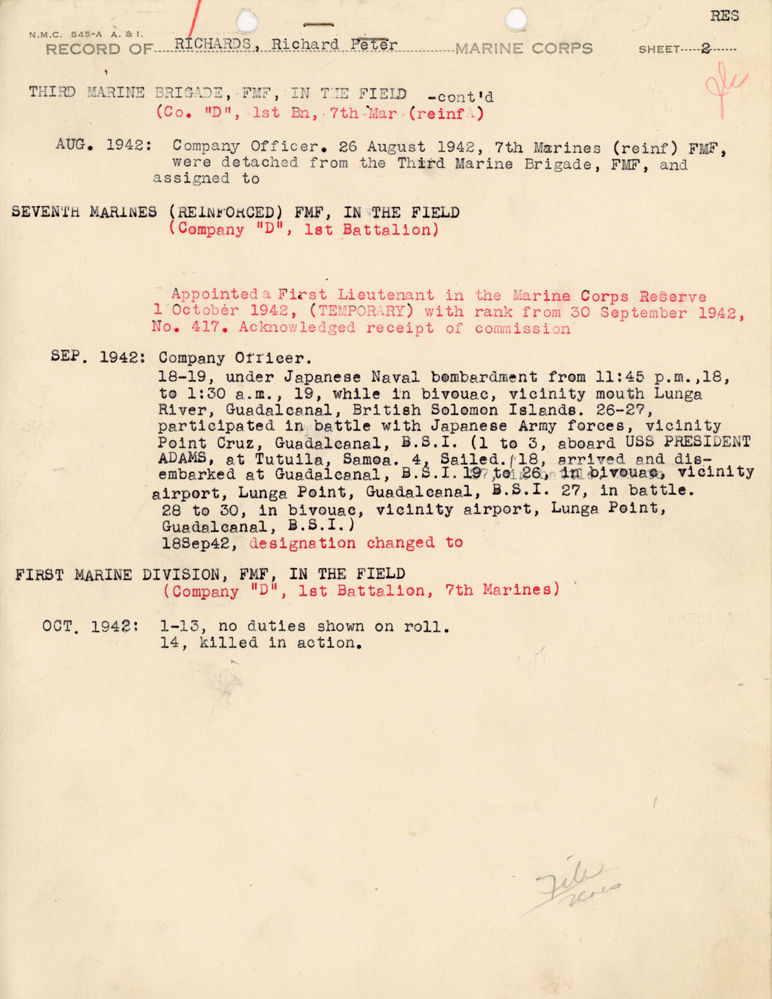

Military Career

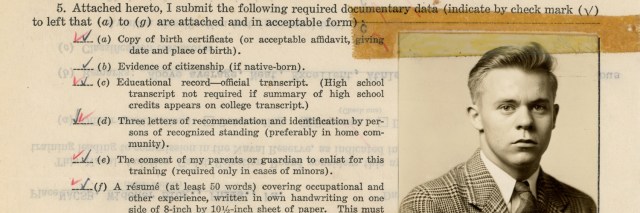

Around March 1941, Richards began obtaining recommendation letters to apply for officer training in the U.S. Marine Corps. Remarkably, this included letters from not only the president of the Atlas Powder Company, his father’s firm, but also the presidents of Atlas’s two main competitors, the Hercules Powder Company and the DuPont Company!

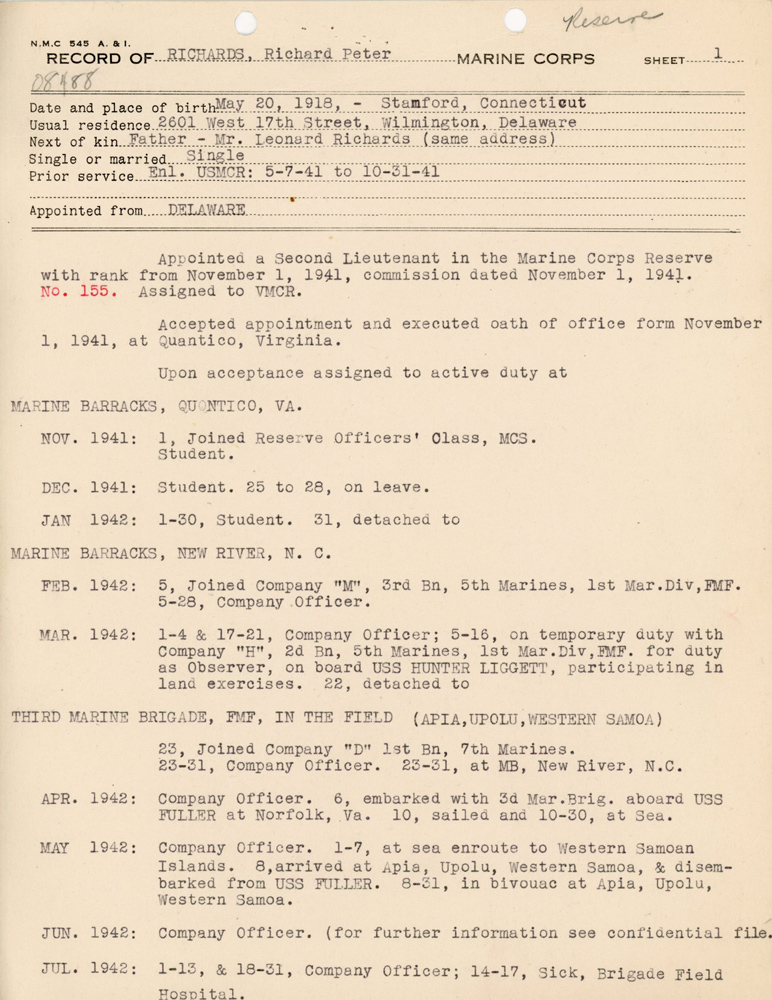

On May 7, 1941, shortly before he graduated from college, Richards enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve in Massachusetts and was placed on inactive duty. As was customary for Marine officer candidates, he was appointed to the grade of private 1st class.

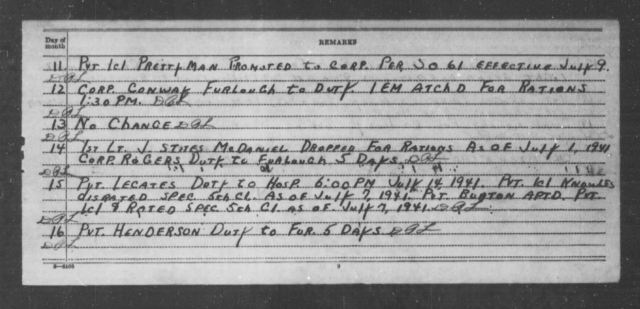

Private 1st Class Richards went on active duty on June 23, 1941, when he began instruction as a student in the 3rd Candidates’ Class, Marine Corps Schools, Quantico, Virginia. He graduated around October 10, 1941. Richards and 309 men successfully completed the course. Another 25 candidates failed to complete the class. On October 25, 1941, an examining board recommended that Richards be appointed as an officer.

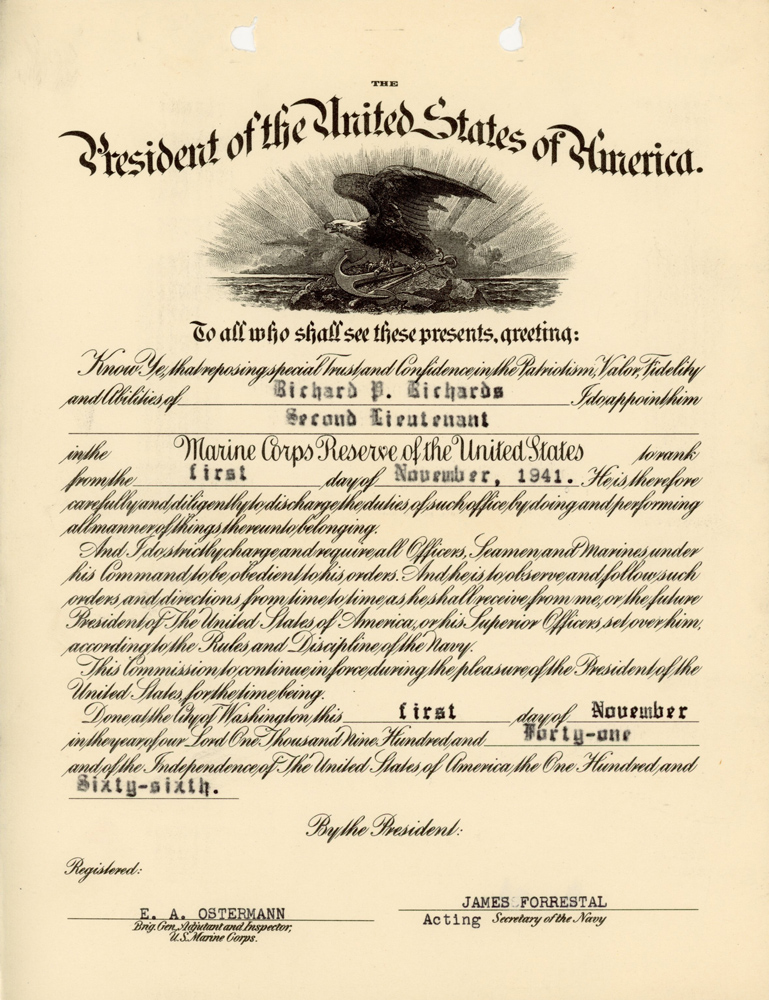

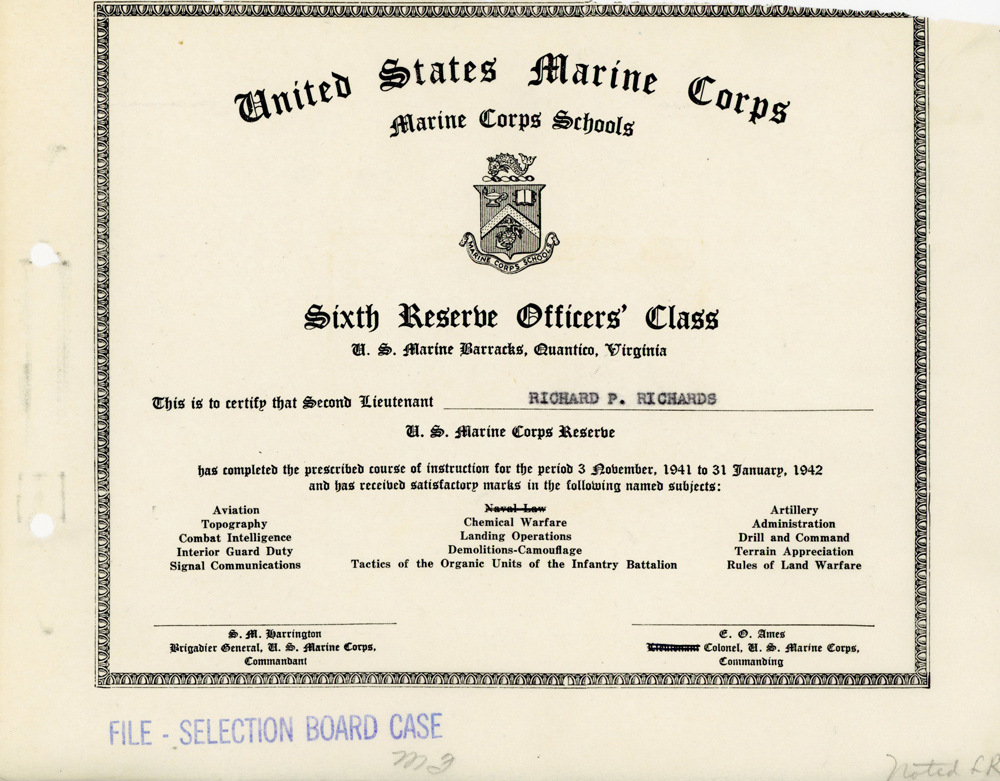

Richards was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve at the Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia, on November 1, 1941. Two days later, he began training as a student in the 6th Reserve Officers’ Class, Marine Corps Schools, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia. Journal-Every Evening reported that Richards and another Delawarean, 2nd Lieutenant Irvin P. Guerke (1917–2003), were in the class, described as “a special course of training in duties of platoon commanders at Quantico, Va.”

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, changed the outlook for Lieutenant Richards and his classmates overnight. He was able to take leave on December 25–28, 1941. After completing his course on January 31, 1942, Lieutenant Richards and 33 of his classmates were dispatched to the Marine Barracks, New River, North Carolina. The officers were permitted up to 10 days’ delay if they had enough leave remaining.

On February 5, 1942, Richards joined Company “M,” 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division. The following month, during March 5–16, 1942, he went on temporary duty as an observer during exercises with Company “H,” 5th Marines. After briefly returning to Company “M,” he was transferred to the new 3rd Marine Brigade on March 22, 1942, which included elements that had been part of the 1st Marine Division. The following day, he joined Company “D,” 7th Marines, 3rd Marine Brigade.

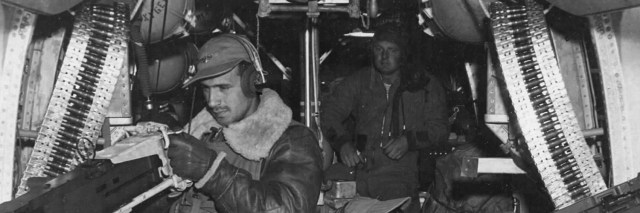

Company “D” was 1st Battalion’s heavy weapons company, which supported the three rifle companies, “A,” “B,” and “C.” Richards was a heavy machine gun platoon leader. The Browning M1917 machine gun, with its heavy tripod and water jacket, was more difficult to carry and set up than the lighter air-cooled machine guns used by the rifle companies, but could sustain a higher rate of fire without overheating.

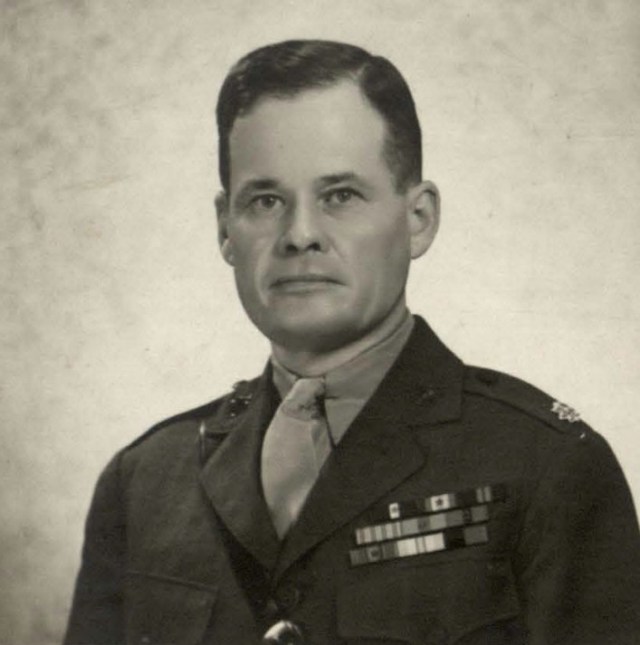

Richards’s battalion commander was the legendary Major (Lieutenant Colonel after May 22, 1942) Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller (1898–1971). Another member of his company was future Medal of Honor recipient John Basilone (1916–1945).

Richards and his battalion departed New River by rail on April 5, 1942, arriving the following day at Norfolk, Virginia. On April 10, 1942, they shipped out aboard U.S.S. Fuller (AP-14), passing through the Panama Canal eight days later. The transport crossed the equator on April 23, 1942. Unless Richards had already done so by sea during travels in his youth, he doubtless endured the hazing of a line-crossing ceremony to graduate from Pollywog to Shellback. The victims included Major Puller, who despite his considerable military experience had never visited the Southern Hemisphere before.

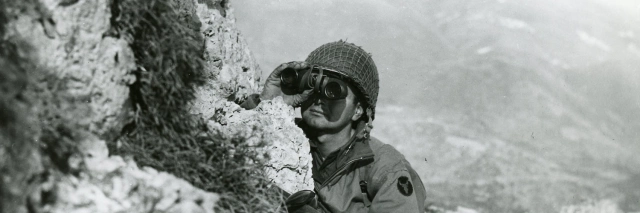

On May 8, 1942, Lieutenant Richards and his men disembarked at Apia, on the island of Upolu, Western Samoa. The following month, on June 12, 1942, they marched west to Faleolo, Upolu. Garrison duty was a disappointment for many of the Marines, though Samoa helped acclimate them for the conditions they would experience during future combat on jungle islands in the Pacific. After preparing defenses in case of Japanese invasion, Richards and his men resumed training. Richards was hospitalized during July 14–17, 1942.

The Battle of Guadalcanal

In the meantime, on August 7, 1942, the Allies began a counteroffensive by landing on Guadalcanal, capturing an airfield they soon renamed Henderson Field. Located in the Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal was at the end of long supply lines for both Japanese and American forces. Though the number of men fighting on the island was miniscule compared with the vast armies engaged in China and Russia at that time, combat on Guadalcanal and in the surrounding waters was still extremely bloody. At the beginning of the campaign, American forces held only the north-central part of the island and were subjected to repeated counterattacks. Without reinforcements, which first had to slip past the enemy’s sea and airpower, neither side could dislodge the other.

On August 16, 1942, Richards and his men returned to Apia. Later that month, on August 27, they reembarked aboard the transport U.S.S. President Adams (AP-38). The following day, they moved to Pago Pago, on the island of Tutuila, American Samoa. They set sail again on September 4, 1942.

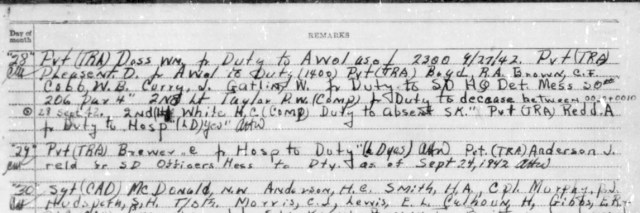

Following brief stops at Tongatapu and Espirito Santo, Richards’s transport arrived on Guadalcanal on September 18, 1942, and the 7th Marines rejoined the 1st Marine Division.

After disembarking and unloading their equipment, Richards and the others moved to a bivouac near the mouth of the Lunga River. That night, the Imperial Japanese Navy welcomed the 7th Marines to Guadalcanal with a naval bombardment. This was a depressingly regular occurrence. At this stage of the war, American aircraft were ineffective at interdicting Japanese ships after dark, and the Japanese were superior to the Americans in night surface combat.

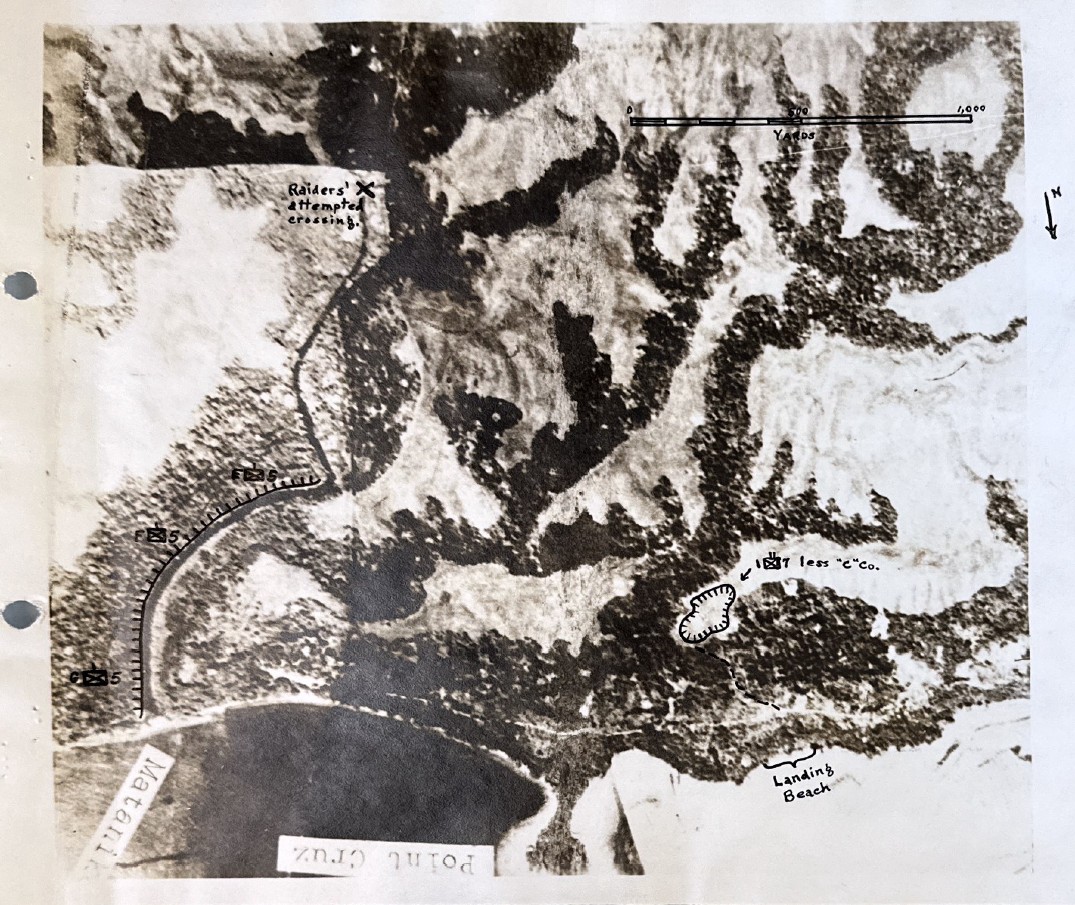

On September 24, 1942, 1st Battalion, less Richards’s Company “D,” began a patrol southwest from the Henderson Field perimeter. That afternoon, they got into an intense firefight with Japanese forces that continued until darkness. The following morning, September 25, Companies “A” and “B” escorted the American casualties back to the perimeter while Lieutenant Colonel Puller took Company “C” and reinforcements from 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines in pursuit. The following day, they patrolled the east bank of the Matanikau River. The enemy was found to be on the west bank near the mouth of the river, and repulsed two attempts by elements of 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines to cross the river. Reinforcements from the 1st Raider Battalion arrived but did not immediately go into action.

A contemporary report stated:

A plan was evolved whereby on Sunday, September 27th, the 2nd Bn., 5th [Marines] would attack across the river mouth; the Raider Battalion would force its way across the river upstream, near the fork; and the 1st Bn., 7th, less “C” Company, would embark in landing boats at Kukum and land in rear of the enemy, west of Point Cruz. Col. Merritt Edson, commanding the Fifth Marines, was to be in charge of the operation.

That plan was not immediately relayed to the main body of 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, back at the Lunga perimeter. In his biography, Chesty, Jon T. Hoffman wrote that the amphibious operation’s commander, 1st Battalion’s executive officer, Major Otho Larkin Rogers (1901–1942), only learned about the mission three hours before his force was scheduled to land.

The inexperienced Major Rogers did not tell Richards or the other 1st Battalion officers about their objectives or any information about their planned movements once ashore. Even so, the operation seemed to start smoothly enough. Richards and 378 other Marines landed unopposed. The battalion, with Company “B” in the lead, began to move inland to a ridge known as Hill 84. Rogers had been told that Japanese strength in the area was 200–300 men. 1st Battalion’s amphibious operation had been intended to block Japanese retreating in under pressure from the 1st Raider Battalion and 5th Marines. Instead, the Japanese 4th Infantry Regiment was strong enough to both repel the American attacks across the river and to deal with the interlopers that had landed to their rear.

Soon after the Marines took Hill 84, they began receiving effective Japanese fire. One of the first shells to land killed Major Rogers and wounded the Company “B” commanding officer. The contemporary report continued:

At about the same time, at the rear of the battalion, a column of Japanese, three abreast, was observed approaching along the coast road, coming from the direction of the Matanikau River. Lt. Richard P. Richards, a machine gun platoon leader, ordered a heavy machine gun set up to cover this column. This gun caused a large number of casualties, until it was overrun and put out of action.

The Japanese attack caught another of Richards’s machine gun squads by surprise at the base of Hill 84, killing or wounding the entire squad except for Private 1st Class Edward R. Poppendick (1923–2007) before they could set up their gun. In an oral history later published in Michael Green and James D. Brown’s book, War Stories of the Infantry: Americans in Combat, 1918 to Today, Poppendick recalled that the enemy was close enough to hear their voices, adding:

I just hugged the ground, figuring my turn was next, so I decided to play dead and stayed that way. Then I heard my lieutenant, Richards, say something. He didn’t know if I was dead, too. He was behind a log about ten or fifteen feet away from me, and when he realized I was still alive, he started hollering, “Do you think you can make it back here?”

I yelled back, “I’ll try it.” I just took the ammunition this way, the spare parts that way, grabbed my rifle, and throom, I must have looked like Jesse Owens running. I hit that log and went over, and all I could hear was a machine gun going, the leaves coming down, and Lieutenant Richards shouting, “Oh boy, this is it!” After I recovered for a while, Lieutenant Richards told me, “Okay, from now on, you’re my runner.” I didn’t think that being a runner was any worse than being a gunner. The thing is that you were scared all the time anyway.

Lieutenant Richards and the men of his battalion were in a precarious situation. The Japanese attack had forced the Marines away from the beach, leaving them encircled in a pocket around Hill 84. Company “D” only had a single 81 mm mortar with just 50 rounds of ammunition. Even more seriously, 1st Battalion had failed to bring any radios on the operation, making it impossible for the surviving officers to get new orders or call for assistance. In desperation, the Marines on Hill 84 pooled their white undershirts to write a single word visible to aircraft operating out of Henderson Field: “HELP.”

A Marine dive bomber pilot relayed the message. In his article, “Little Dunkirk,” Geoff Roecker wrote that “word worked its way down to Chesty Puller himself. Puller knew exactly which unit was in danger, and in typical fashion, exploded into rage-fueled action.” When Colonel Edson refused to launch another futile attack across the Matanikau, Puller yelled, “You’re not going to throw these men away!”

Lieutenant Colonel Puller bore a large share of the responsibility for the predicament his men were in, but he now intervened decisively for their salvation. At 1603 hours, he boarded the destroyer U.S.S. Monssen (DD-436), which had been supporting the assault, and directed fire from the destroyer’s 5-inch guns to clear an escape route. The men of 1st Battalion, the verge of annihilation, managed to fight their way back to the beach under heavy fire, carrying their wounded with them.

Finally, landing craft arrived to extract Richards and the others under intense Japanese fire. The 7th Marines lost 24 men killed and many more wounded in a fiasco that would be known to history as the Second Battle of Matanikau. The 1st Battalion survivors staggered back to the Marine perimeter that night. Richards had likely saved Private 1st Class Poppendick’s life by talking him into self-rescue. As Roecker noted, “no American left ashore survived.”

There was no rest for the weary Marines. 1st Battalion went back into the line the very next day, September 28, 1942. For the time being, no Japanese ground assaults were forthcoming and the men spent their time improving their defenses.

In the first fitness report that Lieutenant Colonel Puller filled out for 2nd Lieutenant Richards after entering combat, covering the period of July 1, 1942, through September 30, 1942, he rated him as good or very good in most categories. He rated Richards as excellent in the categories of physical fitness as well as military bearing, neatness, and loyalty. He was a little weaker, but still rated good, at tactical handing of troops and showing initiative. Perhaps the highest compliment Chesty Puller paid Lieutenant Richards was his answer to the question: “Considering the possible requirements of the service in war, indicate your attitude toward having this officer under your command.” Of the four options, Puller selected the highest possible rating, that he would “Particularly desire to have him[.]”

Richards was promoted to 1st lieutenant on October 1, 1942, with the date of rank September 30, 1942.

In the meantime, a rematch was shaping up along the Matanikau. On the morning of October 7, 1942, Richards’s battalion was among a force that departed the Lunga perimeter. Two days later, they mauled a Japanese battalion west of the Matanikau. Puller wrote in his report:

Known enemy casualties were more than five times our numbers. Our light mortars and rifle grenades were most effective in driving the enemy out of the ravine to our front. Our machine guns then took a heavy toll as they attempted to gain the next ridge to their rear, the slope of which was bare.

The Longest Night

Japanese superiority in night naval combat and the daytime threat of American aircraft operating out of Henderson Field meant that the Imperial Japanese Navy preferred to perform bombardment missions and land reinforcements and supplies under cover of darkness. Only destroyers had the speed to make it to Guadalcanal from other bases in the Solomon Islands and get to safety before daybreak. The Americans referred these missions as the Tokyo Express.

The Tokyo Express had considerable disadvantages. Destroyers consumed more fuel and had less cargo capacity than cargo ships and transports. Japanese planners decided to risk dispatching a slow convoy loaded with reinforcements and supplies on October 13, 1942, even though it would not reach Guadalcanal until the following night. To neutralize the American airpower, which would have likely annihilated such a vulnerable convoy, the Japanese also dispatched the battleships Kongo and Haruna under the command of Vice Admiral Kurita Takeo (1889–1977) to attack Henderson Field that night before the convoy came into range of American airpower.

When the Japanese bombardment force arrived, 1st Battalion was in reserve near Henderson Field. For once, Richards and his men would have been safer on the front lines. During the early morning hours of October 14, 1942, the two battleships pounded Henderson Field and the surrounding positions with their main batteries for 83 bone jarring minutes. For the men in and around the airfield, it was an eternity. On average, every minute, 11 powerful high explosive shells, each weighing over half a ton, rained down around them.

The 7th Marines had been shelled before, but this night they experienced terror incomparable to their previous experiences. Battleship main battery shells weighed about five times as much as those fired by heavy cruisers and 50 times those of destroyers. The difference between being on the receiving end of cruiser fire and battleship fire was analogous to the difference between standing in the middle of a thunderstorm and standing outside in the middle of a Category 5 hurricane. In his book, Strong Men Armed: The United States Marines Against Japan, Robert Leckie (1920–2001), himself a Guadalcanal veteran, wrote:

Men in their holes could hear the soft hollow thumping of the salvoes to seaward, see the flashes shimmering outside the gun ports, and then the great airy boxcars rumbling overhead, wailing and straining—hwoo-hwooee—seeming to lose breath directly overhead, to pause, whisper, and go on. Then the triple tearing crash of the detonating shells and the bucking and rearing of the very ground beneath them.

[…]

Shelters shivered, sighed, and came apart. Foxholes buried their occupants. […]

Men whimpered aloud. Others burst into sobs and rushed from the pits rather than betray their weakness, if such it was, before comrades. There were Marines who put their weapons to their heads. Men prayed with lips moving silently across the backs of others against whom they lay huddled, prayed in confusion—mentally murmuring Grace or a childhood refrain as though it were the Lord’s Prayer—prayed for the strength to stay where they were, to suppress that nameless thing fluttering within them.

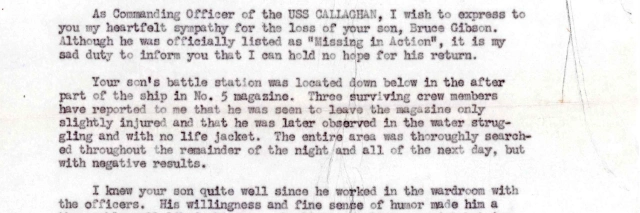

There is no record of whether the shell that killed Lieutenant Richards was fired by the battleships or their escorts, nor any account that reveals whether it was the 10th, or the 100th, or the 900th shell of the bombardment.

The attack proved to be the single most devastating blow against Henderson Field during the entire campaign, destroying over half of the American aircraft at the field and temporarily rendering the runways unusable, permitting the Japanese convoy to reach Guadalcanal safely. A muster roll entry stated that 1st Lieutenant Richards “died about 1:00 a.m. of injuries [received from] direct hit on bomb shelter during enemy naval bombardment[.]” Another Company “D” officer, Jake Daniel Iseman, Jr. (1917–1942) was also killed in the same shelter. In total, 41 Americans died in the attack. Richards was temporarily buried at the 1st Marine Division Cemetery later the same day.

The bombardment was the first and only time American ground troops were on the receiving end of fire from enemy battleships. The following month, during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, the U.S. Navy intercepted two subsequent attempts at great cost. For the rest of the war, whenever battleships conducted shore bombardment, it would be Axis troops on the receiving end.

In his final officer fitness report for 1st Lieutenant Richards, Lieutenant Colonel Puller rated him as excellent overall. He rated him as very good to excellent in all areas except physical fitness, which was outstanding.

His personal effects included a wristwatch, two keys, his wallet, eight coral beads, and a pair of checkbooks. In addition to his standard issued Marine gear, he brought pairs of tennis shoes, moccasins, and sheepskin slippers to Guadalcanal.

Journal-Every Evening reported that Lieutenant Richards’s parents were notified of his death on November 19, 1942. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. During his career, he also earned the American Defense Service Medal and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal. For the collective actions of its members, the 1st Marine Division, Reinforced, was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

After the war, Richards’s mother requested that her son remain in a permanent overseas cemetery. However, all the temporary American cemeteries at battlefields across the Pacific were consolidated into just two permanent cemeteries. Lieutenant Richards was reburied at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii on January 12, 1949. The initial casualty report erroneously listed Lieutenant Richards as being killed in action on October 13, 1942. Although the error was corrected in most records during 1942 and 1943, it still ended up as the date of death on his headstone. Lieutenant Iseman’s headstone is also incorrect.

Lieutenant Richards is also honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Father and Brother

There is considerable variation in the names listed for Richards’s father: Leonard Richards, Leonard D. Richards, and Leonard Richards, Jr. His brother’s name is even more confusing: Leonard Richards; Leonard Richards, II; Leonard Richards, Jr.; and Leonard Richards, III.

Naval Support at Second Battle of the Matanikau

The contemporary report of Second Battle of the Matanikau stated that the “USS Ballard was assigned to support the landing” of the 1st Battalion amphibious force, but due to an air raid, “took evasive action to escape bombing, and the landing was made without support.”

The anonymous author of the report must have been mistaken about the identity of the ship that was supposed to support the operation. U.S.S. Ballard (AVD-10) was an auxiliary seaplane tender, a strange choice to support an amphibious landing. Furthermore, Ballard’s war diary reported that that the previous afternoon, the ship departed Gavutu—located across Ironbottom Sound from Guadalcanal—bound for Espiritu Santo. At the time of the operation, the seaplane tender was well southeast of Guadalcanal, and the ship’s war diary made no mention of any fire support mission nor air attack.

U.S.S. Monssen’s war diary documents that at 1212 hours on September 27, 1942, “Received Major Wolf on board to direct shore bombardment in support of Marine operations on Matanikau River.” An entry at 1245 reported: “Fired 100 rounds 5″ on Japanese person[n]el and installations at points designated.” Only at 1352 did the destroyer encounter enemy aircraft.

These entries make it clear that Monssen rather than Ballard was assigned to the operation from the beginning and Lieutenant Colonel Puller boarding her to direct fire in support of his battalion was not the result of a chance encounter. If 1st Battalion’s landings were not supported by naval gunfire, then, it was because Major Wolf did not direct the destroyer to shell the correct location, not because of the distraction of the Japanese air raid, which Monssen did not encounter for another hour.

Remarkably, although Jon T. Hoffman identified the discrepancy, he included the inaccurate version of events in his biography, Chesty, confining discussion of the matter to an endnote. He concluded: “In all probability, division had arranged for support from Monssen, not Ballard, but in the absence of conclusive proof, I have followed the previously accepted version of events surrounding the landing of 1/7.”

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Geoff Roecker for contributing information and a photo and to Williams College Special Collections for use of a photo from the school’s 1941 yearbook.

Bibliography

“Atlas Man’s Widow Dies.” Journal-Every Evening, February 20, 1959. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153928863/

Brokenshire, D. B. War Diary for U.S.S. Ballard (AVD-10) for September 1942. World War II War Diaries, Other Operational Records and Histories, c. January 1, 1942–c. June 1, 1946. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/134008914

Census Record for Richard Richards. January 2, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9R67-TY3

Census Record for R. Peter Richard [sic]. April 17–18, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MR-MSFH

Census Record for R. Peter Richards. April 2, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRHM-PFL

“Crash Victim Son of First Racing Head.” Journal-Every Evening, July 31, 1959. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153918459/

Draft Registration Card for Leonard Richards, Jr. June 5, 1917. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9BLX-J4M

Draft Registration Card for Richard Peter Richards. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-XDX5

Green, Michael and Brown, James D. War Stories of the Infantry: Americans in Combat, 1918 to Today. Zenith Press, 2009.

The Gulielmensian 1941. The McClelland Press, 1941. https://librarysearch.williams.edu/discovery/delivery/01WIL_INST:01WIL_SPECIAL/12288956160002786

Hoffman, John T. Chesty: The Story of Lieutenant General Lewis B. Puller, USMC. Random House, 2002.

Indenture Between Harrison W. Howell and Lillian S. Hall, Parties of the First Pary, and Leonard Richards, Junior, Party of the Second Part. December 13, 1923. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_256987-00173

Interment Control Form for Richard Peter Richards. 1949. Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/137082234?objectPage=1899#object-thumb–1899

“Irvin P. Guerke.” The News Journal, July 18, 2003. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153920608/

“James Phinney Baxter III.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/247681633/james-phinney-baxter

Leckie, Robert. Strong Men Armed: The United States Marines Against Japan. Originally published in 1962, republished by Da Capo Press, 2010.

“Lieut Jake Daniel Iseman.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/71101814/jake-daniel-iseman

“Lieut. Richards, Wilmington, Killed in Action With Marines.” Journal-Every Evening, November 20, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153927673/

“Maj Otho Larkin Rogers.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56757508/otho-larkin-rogers

Medical Examiner’s Certificate of Death for Leonard Richards, Jr. July 31, 1959. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQ9-9MD

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U. S. Marine Corps Candidates’ Class, MCS, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Va. From 1 June, to 30 June, 1941 inclusive.” June 30, 1941. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/195487984?objectPage=367

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U. S. Marine Corps Company ‘D’, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, First Marine Division, FMF. From 1 October to 31 October, 1942, inclusive.” October 31, 1942. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/195916594?objectPage=412

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U. S. Marine Corps Company ‘D’, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, Reinforced, Fleet Marine Force, AP–B At Anchor, Straw. From 1 August to 31 August, 1942, inclusive.” August 31, 1942. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/195499034?objectPage=304

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U. S. Marine Corps Company ‘D’, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, Third Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, Aboard U.S.S. Fuller, At Sea. From 1 April to 30 April, 1942, inclusive.” April 30, 1942. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/195914875?objectPage=191

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U. S. Marine Corps Company ‘D’, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, Third Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, in Bivouac, Vicinity of Apia, Upolu, Western Samoa. From 1 May to 31 May, 1942, inclusive.” April 30, 1942. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/195493828?objectPage=148

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U. S. Marine Corps Company ‘D’, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, Third Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, in the Field. From 1 July to 31 July, 1942, inclusive.” April 30, 1942. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/195509954?objectPage=66

Official Military Personnel File for Richard P. Richards. Official Military Personnel Files, 1905–1998. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Puller, Lewis B. “Summary of operations of First Battalion, Seventh Marines, 7 – 9 October, 1942.” October 10, 1942. Records Relating to United States Marine Corps Operations in World War II, 1939–1949. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Puller, Lewis B. “Summary of operations of the First Battalion, Seventh Marines, period 24–26 October, 1942.” October 27, 1942. Records Relating to United States Marine Corps Operations in World War II, 1939–1949. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Puller, Lewis B. “Summary of operations of the First Battalion, Seventh Marines, period 27 October, 1942.” October 28, 1942. Records Relating to United States Marine Corps Operations in World War II, 1939–1949. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Racing Chairman Dies in Hospital.” Wilmington Morning News, December 27, 1946. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153914005/

Richards, Leonard. Individual Military Service Record for Richard Paul Richards. January 16, 1944. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20498/rec/1

Roecker, Geoffrey. “Little Dunkirk.” Missing Marines website. https://missingmarines.com/articles/little-dunkirk/

Roecker, Geoffrey. “Otho Larkin Rogers.” Missing Marines website. https://missingmarines.com/otho-l-rogers/

“The Second Battle of the Matanikau.” Undated, c. 1944. Records Relating to United States Marine Corps Operations in World War II, 1939–1949. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Two Wilmington Youths Given Training as Marine Officers.” Journal-Every Evening, February 10, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/153920063/

“War Diary U.S.S. Monssen (436) From: September 9, 1942 To: October 7, 1942.” World War II War Diaries, Other Operational Records and Histories, c. January 1, 1942–c. June 1, 1946. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/133990900

Last updated on October 1, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.