| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York | College student |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 12221393 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Medical Detachment, 346th Infantry Regiment, 87th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 657 (litter bearer) | Rhineland campaign |

Early Life & Family

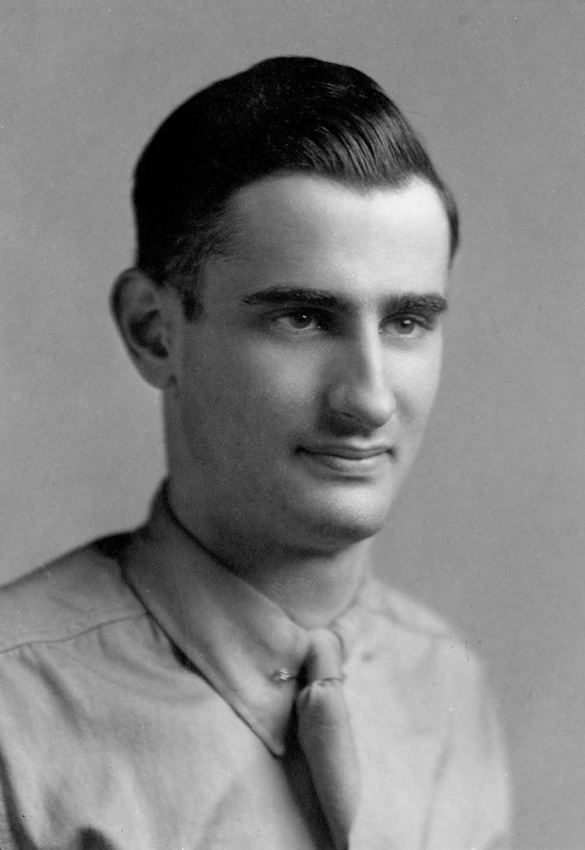

Morton Wolson was born at the Delaware Hospital in Wilmington, Delaware, early on the morning of June 2, 1925. He was the first child of Julius Wolson (then an export manager, 1896–1973) and Zipporah Wolson (née Topkis, 1900–1960). At the time, his parents were living at 811 West 19th Street in Wilmington. Wolson’s family was living at the same address as of November 4, 1928, when his younger sister was born. Wolson was Jewish.

Wolson was recorded on the census in April 1930 living in Wilmington with his parents and sister at the home of his maternal grandmother, Esther M. Topkis (c. 1873–1943), 2302 Baynard Boulevard. His father was working as a clothing salesman.

Census records indicate that as of April 1, 1935, the Wolson family was still living in Wilmington. However, by the time Wolson had his bar mitzvah on June 11, 1938, his family had moved to 1505 Nedro Avenue in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and were members of the Beth Sholom Congregation there. Newspapers also indicate that Wolson also lived in Chester, Pennsylvania, at some point. The next census, taken in April 1940, recorded Wolson living with his parents and sister at 31-21 80th Street in the Jackson Heights neighborhood of Queens, New York.

Journal-Every Evening reported that Wolson “attended Public School No. 30”—now the site of the Baynard House in Wilmington—“and then attended schools in New York City, where he was graduated from the William Cullen Bryant High School. He then enrolled in the pre-medical course at New York University.” His father also told the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission that Wolson attended N.Y.U. On the other hand, Young American Patriots stated that Wolson attended the City College of New York. His enlistment data card stated that Wolson had completed one year of college before entering the service.

Military Training

At the end of 1942, virtually all voluntary enlistment in the American armed forces ended by an executive order which made local draft boards responsible for selecting most of the men who would serve from that point through the end of the war. An exception to the rule was that 17-year-olds could still volunteer. One potential recruiting angle the U.S. Army had for young men, who might have otherwise volunteered for the U.S. Navy or Marine Corps, was the Army Specialized Training Program (A.S.T.P.). Those who passed a test and were selected for the program—typically through Specialized Training and Reassignment (S.T.A.R.) units—would attend accelerated classes at participating colleges across the nation in the hope of enriching the Army with soldiers possessing valuable language or technical skills.

Shortly before his 18th birthday, Wolson enlisted in the U.S. Army in New York City on May 26, 1943. He was temporarily transferred to the Enlisted Reserve Corps (E.R.C.) on inactive duty. Although the Navy and Marine Corps usually began training 17-year-olds immediately after enlistment, the Army did not call up men until after their 18th birthday. According to his father’s statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission, Private Wolson began active duty on November 19, 1943.

After going on active duty, Private Wolson was briefly attached unassigned to Company “C,” 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey. Men selected for A.S.T.P. had to attend basic training first. Wolson was in a group of men, all of them volunteers from the E.R.C. who were candidates for A.S.T.P., ordered to proceed by rail on December 1, 1943, to the A.S.T.P. Basic Training Center (B.T.C.), Fort Benning, Georgia, per Special Orders No. 324, Headquarters 1229th Reception Center, dated November 30, 1943. At 0215 hours on December 3, 1943, Wolson and 239 other men from the 1229th Reception Center were attached unassigned and joined 10th Company, 5th Training Regiment, A.S.T.P. B.T.C at Fort Benning.

Early in 1944, the Army decided to dismantle virtually the entire A.S.T.P. due to projected manpower shortages in combat areas and transfer its personnel to other units. For that reason, Private Wolson was not transferred to a college to begin classes after completing his basic training at Fort Benning. On or about March 17, 1944, Wolson and a group of men transferred by rail to the 87th Infantry Division at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, per Special Orders No. 25, Headquarters Station Complement Unit 3410 S.T.A.R. A.S.T.P., dated March 14, 1944.

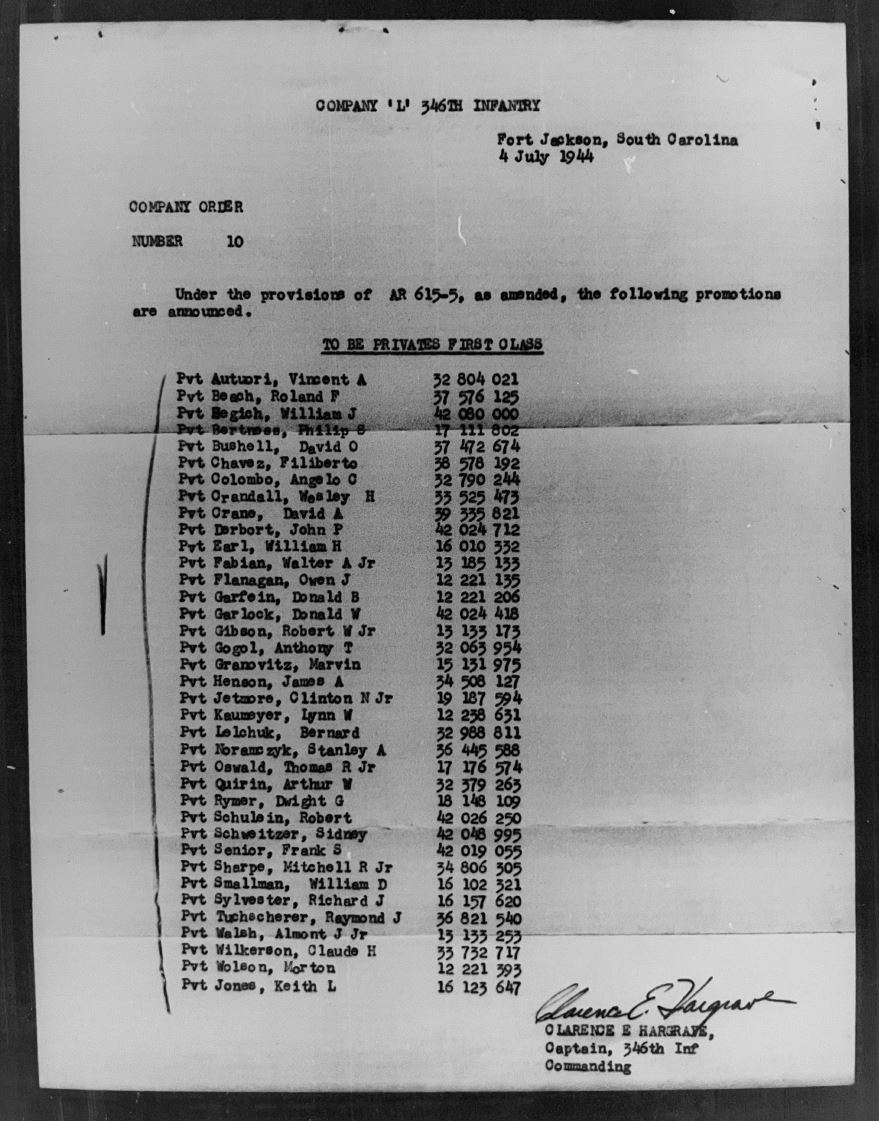

Private Wolson and 14 other men from his A.S.T.P. unit were assigned to Company “L,” 346th Infantry Regiment per Special Orders 68, Headquarters 87th Infantry Division, dated March 20, 1944. At the time, Wolson’s military occupational specialty was recorded as 745, rifleman. A Company “L” morning report described the men as attached for rations and quarters until they became full members effective March 22, 1944. He was promoted to private 1st class on July 4, 1944. The following day, he transferred to the Headquarters Company, 346th Infantry Regiment. His military occupational specialty at the time was still listed as rifleman. On August 8, 1944, Wolson transferred to the Medical Detachment, 346th Infantry Regiment.

His father’s statement suggests that Private Wolson was attached to Company “A” in the same regiment on September 5, 1944, and that as of September 7, 1944, he was a “First Aid Man” attached to Company “A.” Whether or not that was the company that he later supported in combat, technically, Medical Department personnel were attached to a rifle platoon or company rather than being considered members of that unit. As such, Wolson’s unit remained the Medical Detachment, 346th Infantry. Private 1st Class Wolson’s specification serial number code was subsequently recorded as 657. A 657’s title could be medical aidman but varied by the type of unit. In the context of an infantry regiment’s medical detachment, a 657 was a litter bearer.

Wolson’s unit left Fort Jackson on October 9 or 10, 1944, arriving soon after at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, a staging area for the New York Port of Embarkation. On October 16, 1944, his regiment moved to the New York Port of Embarkation, shipping out the following day aboard the ocean liner-turned troop transport Queen Elizabeth.

The 346th Infantry disembarked at Gourock, Scotland, during October 22–24, 1944. Wolson and his unit soon moved south to Cheshire, England. They shipped out from Southampton on November 26, 1944. According to a contemporary unit history, the regiment disembarked at Le Havre, France, on November 27, 1944, while an after action report listed the following day, November 28, 1944. On December 5, 1944, they began moving by road and rail to the area of Metz, France, arriving two days later.

Combat in the European Theater

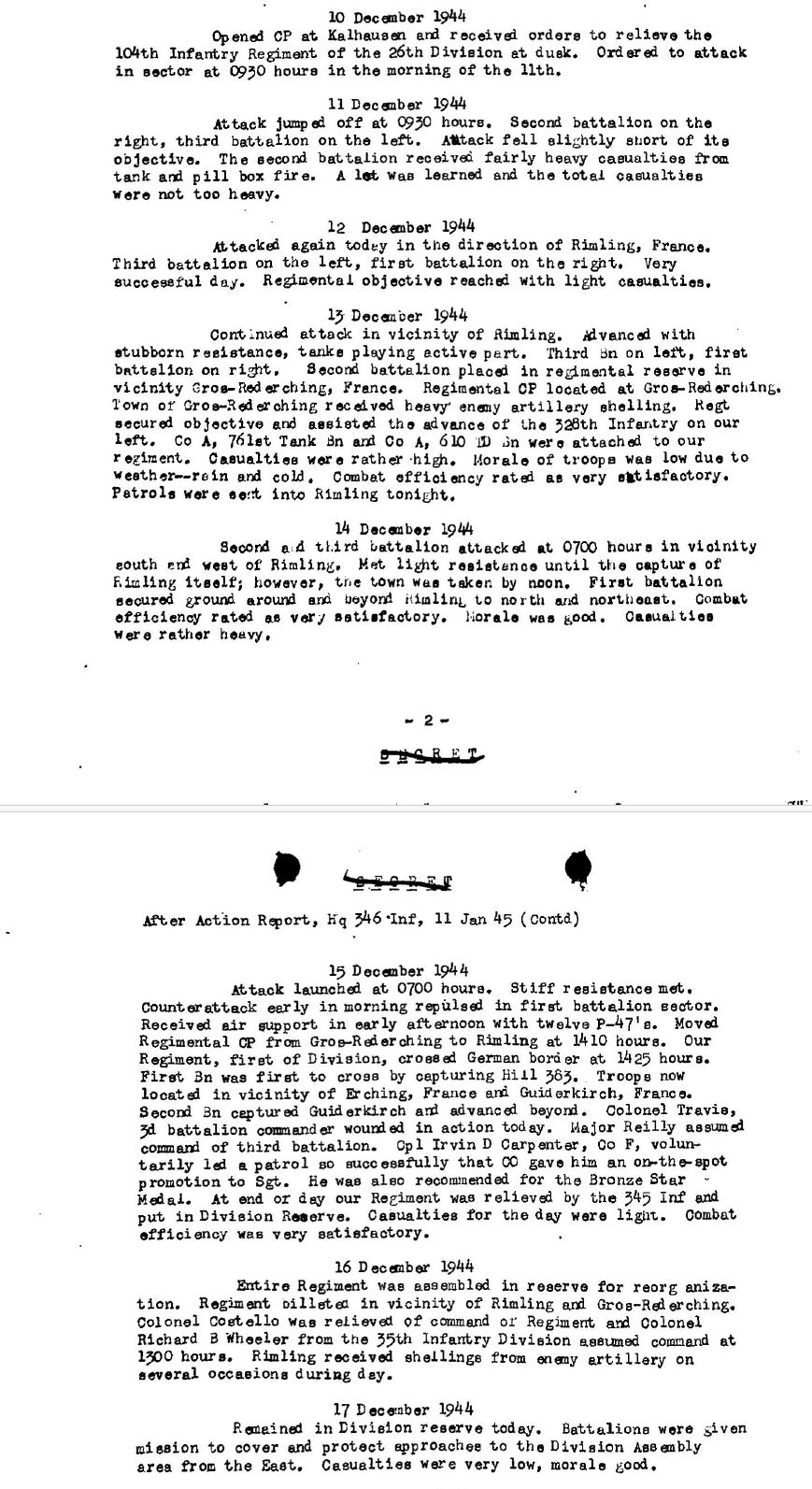

The 346th Infantry Regiment went into the line near Kalhausen, Lorraine, France, on December 10, 1944, relieving the 104th Infantry Regiment, 26th Infantry Division. The regiment wasted no time going into action, launching an attack at 0930 hours the following morning, with 2nd and 3rd Battalions spearheading the advance. The report noted that the assault “fell slightly short of its objective. The second battalion received fairly heavy casualties from tank and pill box fire.”

1st and 3rd Battalions continued the advance on December 12, 1944. The after action report stated: “Very successful day. Regimental objective reached with light casualties.” By December 13, the 346th Infantry had reached the area of Rimling, with 1st and 3rd Battalions securing the day’s objectives with armored support.

The report stated that on December 14, 1944:

Second and third battalion[s] attacked at 0700 hours in vicinity south and west of Rimling. Met light resistance until the capture of Rimling itself; however, the town was taken by noon. First battalion secured ground around and beyond Rimling to north and northeast. Combat efficiency rated as very satisfactory. Morale was good. Casualties were rather heavy.

At 0700 hours the following day, December 15, 1944, the 346th Infantry advanced again:

Attack launched at 0700 hours. Stiff resistance met. Counterattack early in morning repulsed in first battalion sector. Received air support in early afternoon with twelve P-47’s. […] Our Regiment, first of Division, crossed German border at 1425 hours. First Bn was first to cross by capturing Hill 383. Troops now located in vicinity of Erching, France[,] and Guiderkirch, France. […] At end o[f] day our Regiment was relieved by the 345 Inf and put in Division Reserve. Casualties for the day were light. Combat efficiency was very satisfactory.

The following day, the 346th Infantry was in reserve near Gros-Réderching and Rimling, France. The regiment was also in reserve on December 17, 1944, though it was tasked “to cover and protect approaches to the Division Assembly area from the East. Casualties were very low, morale good.”

According to his burial report, Private 1st Class Wolson was shot in the head and killed near Gros-Réderching on December 17, 1944. It is possible that neither the location nor the date are entirely accurate. The burial report initially listed his date of death as December 15, 1944, before being altered. It was not uncommon for burial reports to list an estimated date of death and for that to be subsequently corrected. However, it is notable that the 346th Infantry went into reserve December 15, 1944, and that Gros-Réderching was the site of the regimental command post from December 13–15 but was well behind the lines by December 17.

Although it is certainly plausible that Wolson was the victim of German straggler or even an accidental shooting by another American soldier during the mission to protect the assembly area, it is also true that a significant number of fallen Delawareans’ official dates of death were recorded while their units were in reserve. In at least some of those cases, this was no coincidence, given that accurate recordkeeping was extremely difficult in combat. Sometimes it was not possible to properly account for personnel until a unit was pulled out of the line. Although a casualty report could be backdated when a specific date of death was known, when accurate information was unavailable they were never submitted with a possible range of dates. In the end, every fallen soldier needed an official date of death, even if that date was when his death was reported, not when it happened.

Based on available information, it entirely possible that Private 1st Class Wolston was killed in action during the heavy fighting on December 15, 1944, the original date on his burial report, but all that is certain is that he was killed sometime during December 11–17, 1944.

Wolson’s personal effects included two wallets, a wristwatch, and 16 photos.

Wolson was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. Although not substantiated in other known sources, Young American Patriots stated that Wolson earned the Bronze Star, Purple Heart with one oak leaf cluster, and the Good Conduct Medal. Wolson would have been eligible for the Combat Medical Badge (C.M.B.), which was introduced the following month and retroactive to the beginning of the war, though there is no evidence he was ever officially awarded it. A 1947 decision also made it possible to award the Bronze Star Medal retroactively to soldiers who received the Combat Infantryman Badge or C.M.B. during World War II, but there is no indication he received that decoration either.

Wolson was initially buried at a temporary military cemetery at Limey, France, on December 18, 1944. After the war, in 1948, his parents requested that his body be buried at a permanent cemetery overseas. Wolson was reburied in Saint-Avold, France, at what is now known as the Lorraine American Cemetery. His name is honored on a memorial at the Jewish Community Cemetery in Wilmington and at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Notes

Name

Surviving military records indicate that Wolson served under the name Morton Wolson with no middle initial. Likewise, his birth certificate also gave his name as Morton Wolson with no middle name. Some sources, including Young American Patriots and the individual military service records his father submitted to the State of Delaware Public Archives, list his name as Morton Topkis Wolson.

College

Archivists at New York University and City College of New York were unable to find any record of Wolson attending those institutions, but extant records from those eras are not so comprehensive as to disprove reports that he attended either school.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Matt LeMasters for morning reports that trace Wolson’s transfers and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“Bar Mitzvah Reception.” Journal-Every Evening, June 11, 1938. https://www.newspapers.com/article/155800011/

Census Record for Morton Wolson. April 7, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHM-NHG

Census Record for Morton Wolson. April 16, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MB-94GY

Certificate of Birth for Deborah Wolson. November 7, 1928. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YQM-QG8Y

Certificate of Birth for Morton Wolson. Undated, c. June 2, 1925. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQM-3Y19

Enlistment Record for Morton Wolson. May 26, 1943. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=929&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=12221393&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=74412

Headstone Inscription and Interment Record for Morton Wolson. Headstone Inscription and Interment Records for U.S. Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942–1949. Record Group 117, Records of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1918–c. 1995. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9170/images/42861_646933_0810-01557

“History of 346th Infantry.” Undated, c. 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Morton Wolson. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Morning Reports for 10th Company, 5th Training Regiment, Army Specialized Training Program. December 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0428/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0428-05.pdf

Morning Reports for 10th Company, 5th Training Regiment, Army Specialized Training Program. March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0248/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0248-25.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 1229th Reception Center. November 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002-05.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002-06.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002-07.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0002-08.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “K,” 346th Infantry Regiment. March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0381/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0381-12.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “L,” 346th Infantry Regiment. July 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Matt LeMasters.

Morning Reports for Company “L,” 346th Infantry Regiment. March 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0381/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0381-12.pdf

Morning Reports for Headquarters Company, 346th Infantry Regiment. July 1944 – August 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Matt LeMasters.

Morning Reports for Medical Detachment, 346th Infantry Regiment. August 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Matt LeMasters.

Morning Reports for Medical Detachment, 346th Infantry Regiment. December 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Matt LeMasters.

“Mrs. Esther M. Topkis.” Wilmington Morning News, January 1, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/155841026/

Schuh, Maurice R. “After Action Report.” January 11, 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Wilmington Soldier Killed; Three Others Are Wounded.” Journal-Every Evening, December 29, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/155799667/

Wolson, Julius. Individual Military Service Record for Morton Topkis Wolson. November 3, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/21489/rec/1

Young American Patriots: The Youth of Maryland and Delaware in World War II. National Publishers, Inc., 1950. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8941/images/md_de1-0291

Last updated on August 10, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.