| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| West Virginia, New York, Delaware | Clerk for Sears, Roebuck & Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | Enlisted 32065351 / Officer O-1301865 |

| Theater | Unit |

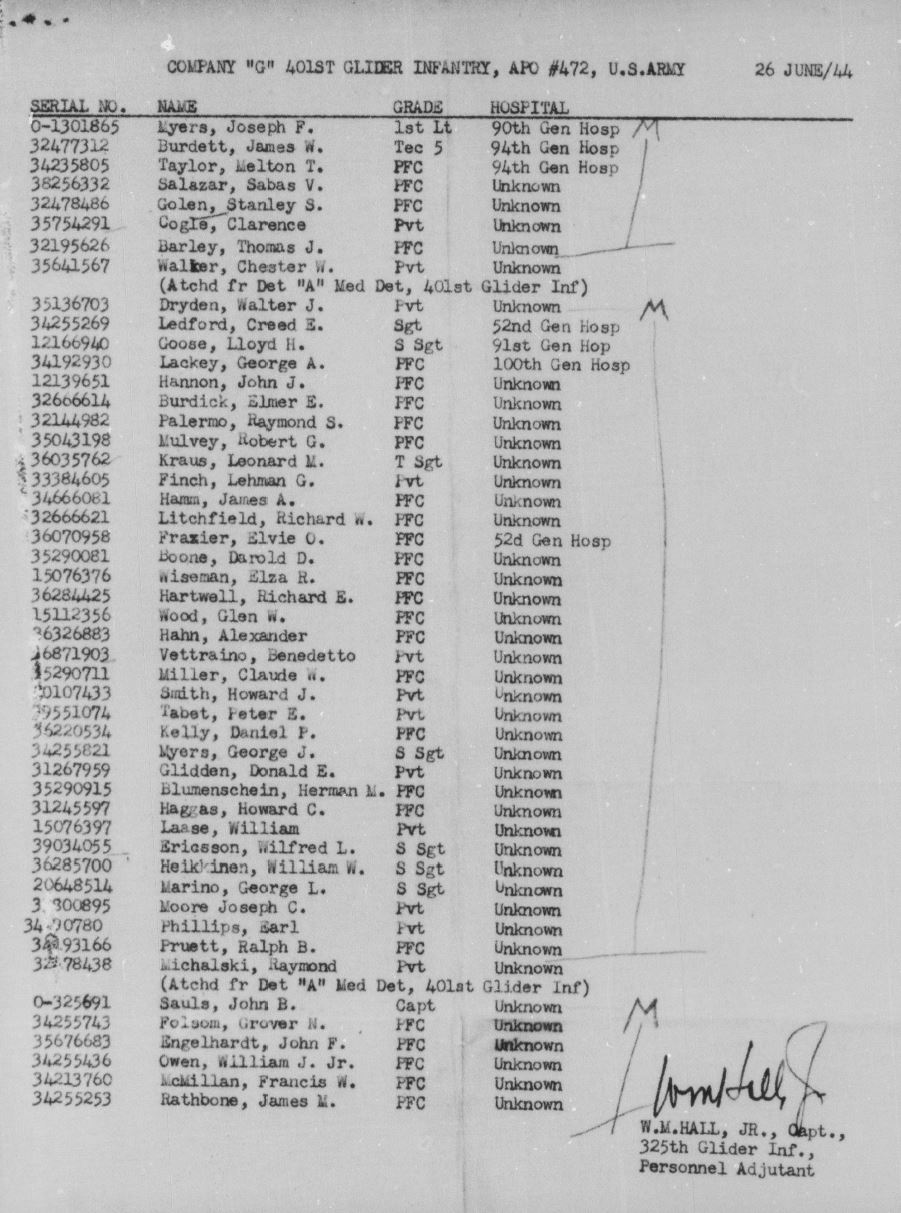

| European | Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Distinguished Service Cross, Purple Heart with one oak leaf cluster, Combat Infantryman Badge | Normandy, Rhineland |

Early Life & Family

Joseph Foss Myers was born in Alderson, West Virginia, on June 19, 1919. Nicknamed Joe (or Junie to some of his siblings), he was the son of Daniel Foss Myers (a farmer, 1892–1942) and Lucille Hattie Myers (or Hattie Lucille Myers, née Griffith, 1893–1982). He had two older sisters—one of whom died prior to his birth—an older brother, five younger brothers, and three younger sisters. He was Presbyterian.

The Myers family was recorded on the census in January 1920 living on a farm in Sweet Springs District, Monroe County, West Virginia. Based on the birth of his siblings, the Myers family was still in Sweet Springs as of April 13, 1921, but had moved to Hartwick, Otsego County, New York, by January 11, 1923.

The Myers family was recorded living in Hartwick on the 1925 state and 1930 federal censuses. Census records also state that the Myers family was living in unincorporated Otsego County as of April 1, 1935. Myers graduated from Hartwick High School on June 28, 1938. As of January 1941, he also had one year of college under his belt through a correspondence school.

On March 18, 1939, Myers’s parents purchased land in South Murderkill Hundred in the area of Magnolia, Kent County, Delaware, along the highway between Frederica and Dover. The property deed described them as already residing in Kent County, though circumstantial evidence indicates that they had only recently moved to Delaware.

Census records state that as of April 1, 1940, the Myers family was living on a farm in the 8th Representative District, in unincorporated Kent County, Delaware. Myers was described as an unpaid farmhand on the family farm.

When he registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, Myers was living in Frederica and working for Sears, Roebuck & Company in Dover, Delaware. His mother told the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission that her son was working there when he entered the service a few months later. Andrew West wrote in a 2008 article in the Delaware State News that “Myers worked in the downstairs plumbing section of Sears Roebuck & Co. in Dover.” According to his induction paperwork, as of January 1941 Myers had one year of experience working as a store clerk, earning $13 per week.

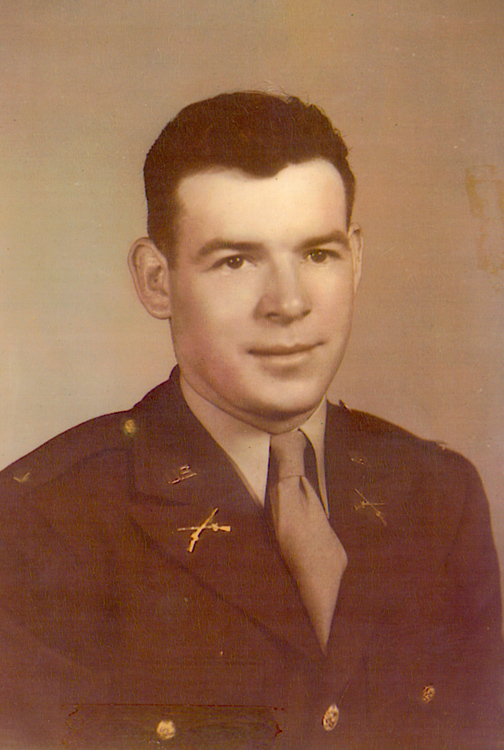

The draft registrar described Myers as standing about five feet, 10 inches tall—a significant overestimate—and weighing 160 lbs., with black hair and brown eyes.

Military Training

Myers was drafted by Kent County Board No. 2 before the American entry into World War II. He joined the U.S. Army on January 7, 1941, at Trenton, New Jersey. According to his military paperwork, at the time of induction, Myers stood five feet, 7¾ inches tall and weighed 155 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. He was briefly attached unassigned to Company “H,” 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey. By January 9, 1941, Myers had been examined and classified as semiskilled with the specification serial number most closely matching his civilian skillset listed as 186, receiving or shipping checker. As subsequent events showed, that did not mean the Army necessarily intended to use him in that role.

During the World War II era, many soldiers were assigned directly to units for basic training rather than first attending at a training center. A set of orders came down, effective January 10, 1941, transferring Myers and 405 other draftees to the 44th Division. The group included at least two other Delawareans destined to lose their lives in the service: James William Bishop (1916–1942) and Augustus George Zografos (1919–1942). The division was originally a New York National Guard unit but after it was federalized on September 16, 1940, soldiers from other parts of the country transferred in.

On January 10, 1941, Private Myers joined Company “I,” 71st Infantry Regiment, 44th Division, also located at Fort Dix. After completing his basic training, Private Myers was assigned the duty of rifleman. He went on furlough during August 17–27, 1941. Myers and his unit traveled by truck to Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Pennsylvania, on September 2, 1941, for “field target firing.” Private Myers was hospitalized on the evening of September 5. He returned to duty on the afternoon of September 8, when his unit returned to Fort Dix. The following month, Myers and his unit moved to the area of Wadesboro, North Carolina, in preparation for the General Headquarters Maneuvers (Carolina Maneuvers) scheduled to begin in the middle of the month.

With the rapid expansion of the U.S. Army, it was possible for a man to advance through the ranks with extraordinary speed. Still, Myers evidently impressed his superiors, since on November 15, 1941, the day before the beginning of the maneuvers, he was promoted two grades to corporal. A roster from the end of that month stated that his military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code was still 745, rifleman, but his duty was now 653, assistant squad leader in the context of his grade.

Following the end of the maneuvers, Corporal Myers and his unit headed back north on or about December 6, 1941. They were still in transit when Pearl Harbor was attacked, arriving back at Fort Dix on December 9. In the fearful days after the U.S. entry into World War II, further enemy attacks—or at least sabotage—appeared possible. On December 24, 1941, Company “I” moved its base of operations to the 113th Infantry Regiment’s armory in Newark, New Jersey. Myers and his comrades spent the holiday season performing guard duty at railroad bridges in the areas of Newark, Jersey City, and Paterson, New Jersey.

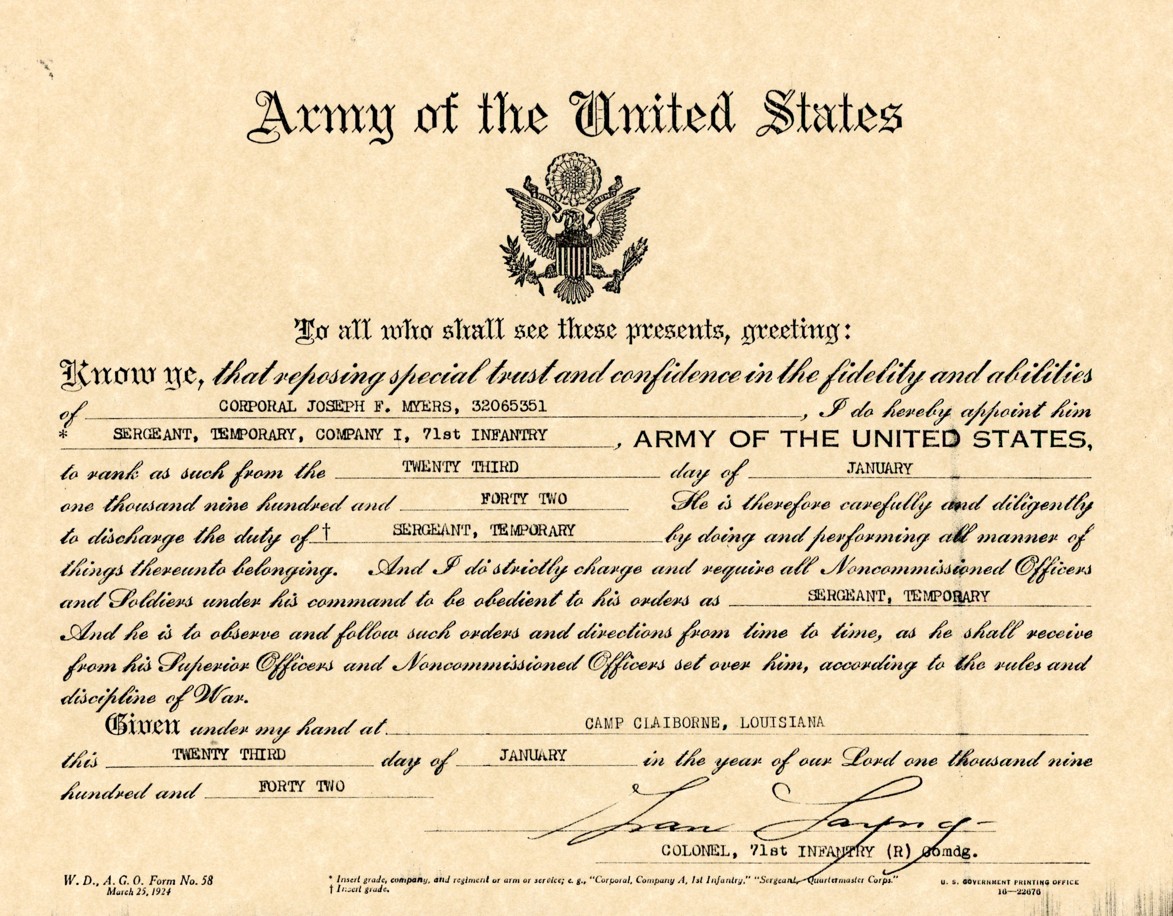

On January 3, 1942, Company “I” returned to Fort Dix to begin preparing for their next change of station. On the night of January 6, 1942, they boarded a train, arriving at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, shortly after midnight on January 9. On January 23, 1942, while still in transit, Myers was promoted to sergeant. His duty remained 653, indicating he had become a squad leader.

Company “I” arrived at Fort Lewis, Washington, late on February 24, 1942, but moved south by road to Camp Bonneville, Washington, four days later.

Sergeant Myers’s father died suddenly of a stroke or heart attack on March 7, 1942. Four days later, Myers went on furlough, presumably back to Delaware. He rejoined his unit, now back at Fort Lewis, on March 27. On the morning of April 8, 1942, Myers went on a special duty assignment with the training cadre at Headquarters 71st Infantry. It is unclear if he remained at Fort Lewis for that entire assignment. He may have moved to Vancouver Barracks, Washington, at some point during that duty. At any rate, on May 18, 1942, he rejoined Company “I,” which was on guard duty at Portland Army Air Base, Oregon. Though it remained headquartered in Portland, on May 26, the company began guarding certain sites on the other side of the Columbia River in Vancouver, Washington, including bridges and an ammunition dump.

On June 29, 1942, Sergeant Myers had a medical evaluation at Portland Army Air Base as part of an evaluation to determine whether he was eligible to attend Officer Candidate School (O.C.S.). The physicians described him as standing five feet, eight inches tall and weighing 170 lbs. They concluded that although Myers had a mild case of pes planus (flat feet) and was partially colorblind, he met the physical requirements to become an officer. A document dated July 13, 1942, stated that Myers had “been tentatively selected by a board of officers for appointment” to the Officers’ Candidate School in the Army of the United States for attendance at the Infantry School.”

On July 30, 1942, Myers was dispatched to Headquarters 44th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis on special duty for another evaluation by a board of officers regarding his application for O.C.S. He returned to duty with his company in Portland at 1400 hours on August 1, 1942, but was hospitalized at 2000 hours that night. He rejoined his company, now stationed at Quillayute, Washington, guarding an airfield and patrolling beaches along the Pacific Ocean, at 1930 hours on August 18.

In late summer 1942, several Delawareans serving in the 71st Infantry were selected to attend Infantry O.C.S. at Fort Benning, Georgia, including Sergeant Myers, Corporal Seymour Miller (1919–1944), and Corporal William B. Weldon, Jr. (1916–1944). At 1000 hours on August 19, 1942, Sergeant Myers was dispatched to Fort Benning, Georgia, on detached service for O.C.S. He officially transferred out of the 71st Infantry effective August 31.

On September 2, 1942, Sergeant Myers was one of 220 enlisted men who joined 31st Company, 2nd Student Training Regiment at Fort Benning, Georgia, taking Infantry Officer Candidate Course No. 113. On November 29, 1942, Myers and 177 other enlisted men from his class were honorably discharged as a formality to accept their commissions the following day. Myers was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant in the Infantry branch on November 30, 1942. He and the other freshly minted officers were temporarily attached to the company for quarters and administration.

At 1630 hours on December 22, 1942, 2nd Lieutenant Myers joined Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The regiment had been activated about four months earlier, on August 16, 1942. Although glider units lacked the paratroopers’ prestige, they were vital to the success of the airborne mission. At that time, heavier equipment, such as vehicles, could only be transported by glider, and the glider units’ manpower and firepower supplemented those of the lean, lightly equipped paratrooper units.

Myers was sick in quarters on January 8, 1943, and hospitalized the following day. He returned to duty on January 13. On January 28, 1943, Lieutenant Myers went on detached service to the Second Army Ranger School, Camp Forrest, Tennessee. The two-week course was the brainchild of Second Army’s commander, Lieutenant General Ben Lear (1879–1966).

In his article, “Commando & Ranger Training Part II, Preparing America’s Soldiers for War,” Charles H. Briscoe explained:

Lear believed that American soldiers must learn to fight dirtier than the enemy and be versatile in their techniques—they had to be adept in the ‘art of killing.’ After observing Marine close combat fighting tactics at Camp Pendleton, California, and touring the Tank Destroyer Center at Fort Hood, Texas, LTG Lear incorporated training aspects from both and first hand battle reports to better Army ground combat fighters—its infantrymen.

Briscoe wrote: “Those men sent to Camp Forrest for Ranger training were to be the most intelligent and physically fit infantry and artillery lieutenants, corporals and sergeants from their divisions.” By selecting junior officers and noncommissioned officers, the goal was not only to increase the combat proficiency of the trainees but to ensure that they would be prepared to train their own men once they returned to their original units. Briscoe added:

The small unit ‘Ranger’ trainees practiced ‘hands on’ before being tested on physical conditioning, hand-to-hand combat skills, bayonet fighting, and combat marksmanship during ‘blitz training’ (immediate action live fire drills). Sniping and infiltration, camouflage, wire obstacles, mines and demolitions, and improvised tank killing were all part of individual training.

Lieutenant Myers attended the second and last Second Army Ranger class. Following the training and three days of leave, Myers rejoined Company “G” at Fort Bragg on February 19. He was hospitalized March 11–19, 1943, and went on leave again April 23–27, 1943. He rejoined his unit at Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, North Carolina. Company “G” returned to Fort Bragg the following month. Early on June 6, 1943, they boarded a train, arriving the following day at Springfield, Tennessee. July 1943 morning reports are missing, but the company returned to Fort Bragg, and Myers was hospitalized again at some point during the month. He returned to duty on August 2, 1943, but went on sick leave again August 4–10. A morning report mentioning his return stated that his duty was Weapons Platoon leader.

Service in England

On the afternoon of August 27, 1943, Lieutenant Myers and his company boarded a train and headed north, arriving at Camp Shanks, New York, early on August 29. Early on September 5, 1943, they moved to the New York Port of Embarkation and boarded the British transport S.S. Strathnaver, setting sail that same day as part of Convoy UT-2. However, on September 11, the ship pulled into port at St. John’s, Newfoundland, for repairs. The unit’s Canadian detour stretched to weeks before Myers and his comrades moved to the M.S. John Ericsson on October 1, 1943. When their new vessel set sail on October 4, however, it was westbound rather than eastbound. The ship put in at Halifax, Nova Scotia, on October 6, to wait for a convoy.

On October 8, 1943, Convoy UT-3 departed New York. John Ericsson sailed from Halifax the same day, rendezvousing with the other ships at sea on October 9. After crossing the Atlantic Ocean safely, John Ericsson finally pulled into Liverpool, England, on the afternoon October 18, 1943. It would be another day before Company “G” disembarked. After an overnight train journey, Myers and his men arrived at Reading, Berkshire, England, on the morning of October 20. They spent most of the next few months there continuing their training. Although Myers would not have been privy to the planning, airborne forces would be integral for the invasion of France that was taking shape for the following year.

Myers was promoted to 1st lieutenant effective December 5, 1943.

At some point after moving to Delaware, Myers had begun dating Dorothy Farrar Coverdale (later Curl, 1923–2013). In 2009, she told the Delaware State News that Myers was “fun-loving and honest, and we were immediately mutually attracted.” It is unclear if the couple was ever formally engaged, though years later she described Myers as her fiancé, and one of Myers’s letters home makes it clear they planned to marry after the war. In a letter to his mother dated January 4, 1944, Myers wrote about Coverdale, then a nursing student:

You know Mother, you have a lot of time to spend with Dot and I later on. […] She also loves her work up there at the hospital and tells me all about it. She says when I get home she will take care of me 24 hours a day. I’ll need it I guess. I think an awful lot of her and if nothing changes I’ll marry her soon after I get back.

On February 13, 1944, Myers and three enlisted men were placed on detached service with the 435th Troop Carrier Group. They returned to duty on February 26, and Myers resumed command of Weapons Platoon.

U.S. Army glider units were organized differently than other infantry units. Most infantry units at the time were “triangular” with three maneuver elements. A standard infantry regiment, for instance, was composed of three battalions, each with three rifle companies. Each of those rifle companies had three rifle platoons, and each of those rifle platoons had three rifle squads. The most common tactical deployment at multiple levels was referred to as “two up, one back.” Put simply, a regiment most often attacked with two battalions, keeping the third in reserve, and the attacking battalions usually had two rifle companies lead an assault while keeping one rifle company in reserve. As of early 1944, however, glider infantry regiments had only two battalions, limiting their combat strength and complicating their tactical deployment. In addition, the 101st Airborne Division had one more glider regiment than the 82nd Airborne Division.

Given that no rebalancing of the glider infantry regiments’ table of organization and equipment were immediately forthcoming, Army planners came up with an ad hoc solution. 1st Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry Regiment would remain with the 101st Airborne Division but would be attached to the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, giving it three battalions. However, on March 10, 1944, Lieutenant Myers’s 2nd Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry Regiment (Companies “E,” “F,” and “G,” plus detachments from the regimental headquarters, service, and medical units) was attached to the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division. The same day, 2nd Battalion moved to Camp March Hare in Scraptoft, Leicestershire, England. Essentially, during the next year, 2nd Battalion of the 401st acted as 3rd Battalion of the 325th.

A company morning report recorded that on April 16, 1944, 1st Lieutenant Myers went on detached service with the 50th Troop Carrier Wing “for the purpose of giving instructions to glider pilots[.]” Journal-Every Evening also reported on the assignment, though the article erroneously claimed that Myers already had been in combat, evidently conflating his experience with that of his fellow instructor:

First Lieut. Joseph Myers, Magnolia, attached to the airborne unit in England, is one of two veterans of two Mediterranean campaigns, who are heading a team of refresher course instructors traveling from one glider unit to another in England.

The story of the work of Lieutenant Myers and Capt. Robert Dickerson, Henderson, Ky., in leading the instruction group is told in Stars and Stripes under [the] date of May 10. A photograph illustrating the story shows Myers giving F-O Clarence B. Clark, Charlotte, N. C. “a workout on the tommy gun as a part of a refresher infantry course for glider pilots.”

The British and Americans had radically different doctrine for the use of glider pilots after landing. British glider pilots were fully trained in ground combat and served as infantrymen after landing. American glider pilots had very limited infantry training and planners wanted them removed from the combat area as soon as practical. The refresher training that Myers and Dickerson conducted did not represent a change in American philosophy about glider pilots but reflected the reality that after landing behind enemy lines, they would likely encounter the enemy before they could be evacuated. Lieutenant Myers rejoined Company “G” on May 16, 1944.

Normandy & Return to England

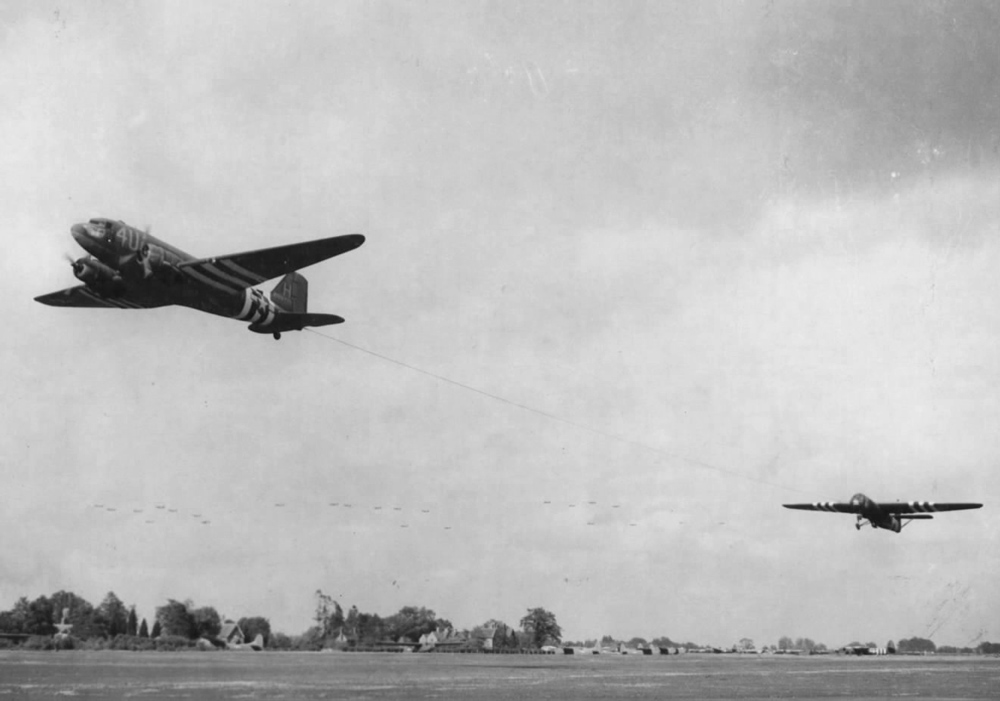

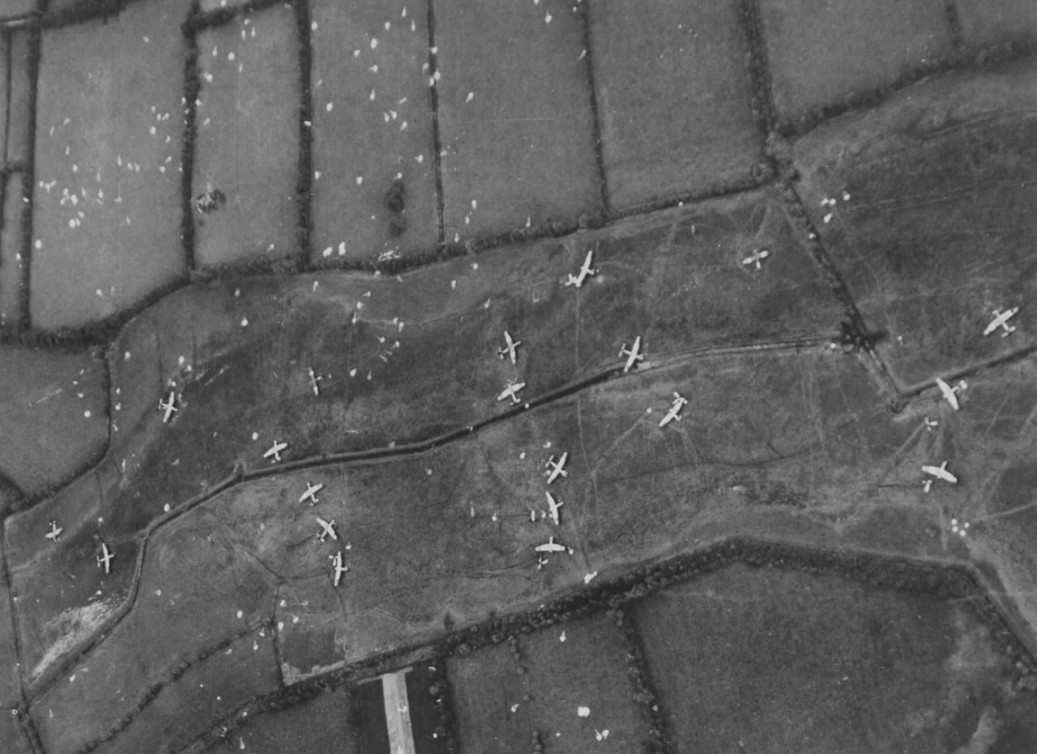

On May 29, 1944, with the beginning of Operation Overlord imminent, Myers and most members of his battalion as well as 2nd Battalion of the 325th Glider Infantry moved to the field at Royal Air Force Upottery, East Devon, England. They were scheduled to land on D+1, the second day of the invasion. Their serial would be loaded onto 50 gliders: 20 American Waco CG-4As and 30 of the larger British glider, the Airspeed Horsa. A contemporary 325th Glider Infantry history report on the Normandy campaign stated:

The period between arrival at the airfields and the take-off for the continent was one of briefing, of last minute issue of [anti-gas] impregnated clothing and the tying in of various stray ends. Apart from that, the Regiment spent its time quietly in the closely controlled conditions of the marshalling areas.

Gliders were loaded with equipment well in advance of D-day, which was one of idleness for the Regiment, spliced with a very keen interest in such news broadcasts as were received. That night maps were distributed to the glider commanders and the passwords for the next three days given out. The mood of the men was quiet and matter of fact.

Early on the morning of June 7, 1944, Myers and his men boarded their Horsa glider, with takeoff around 0645 hours. Although it was a day into the invasion and a daylight operation, unlike airborne operations on D-Day itself, the glider infantrymen took remarkably high losses merely landing in Normandy. The 325th Glider Infantry report explained:

At 0700 the gliders began landing over an area some 2500 yards southeast of Ste Mere Eglise and extending toward the region east of Blosville. The fields available for landing proved to be much smaller than anticipated and the hedges and trees around them much higher than expected. There were many crash landings and some opposition from small arms fire. Mortar shells were also dropping in the landing areas. Landing casualties amounted to about 7.5%[.] On the whole, the CG4A gliders fared better than the Horsas, particularly in condition after landing, but also in casualties. All the 35 deaths from injuries in landing were among passengers in the Horsa gliders.

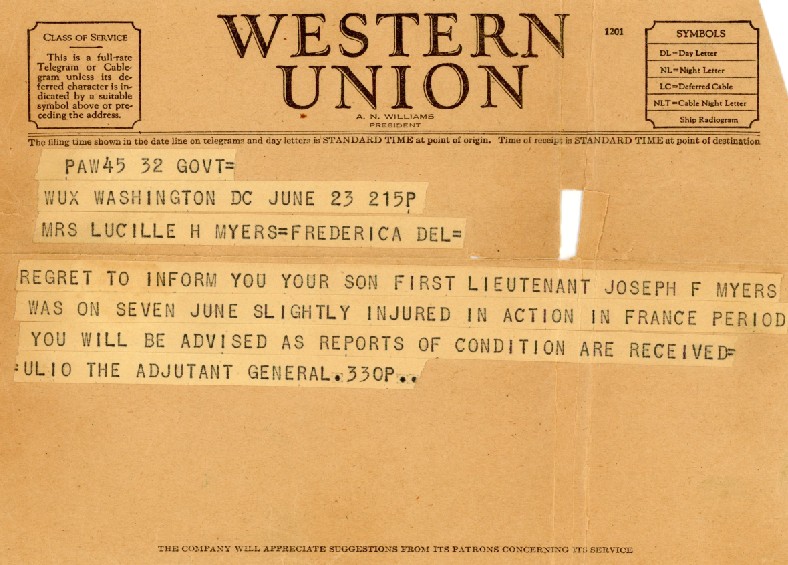

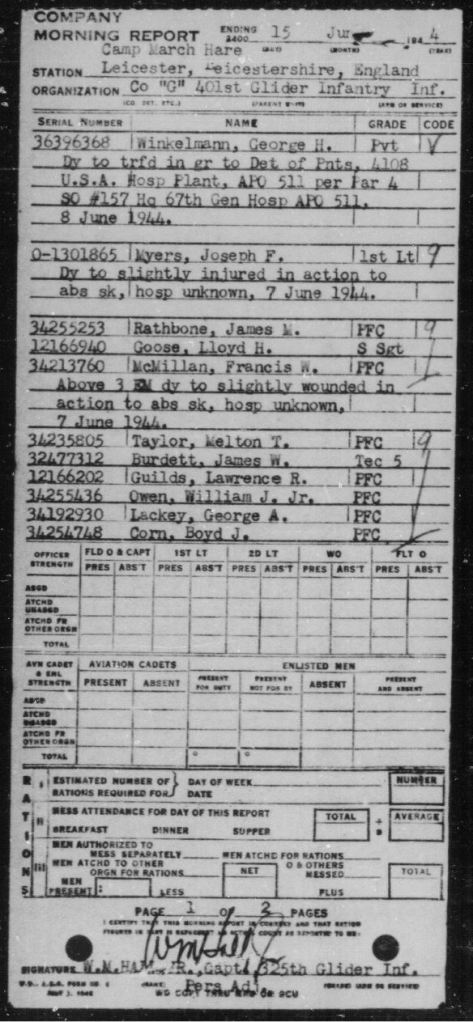

After reaching the landing zone around 0850 hours, Lieutenant Myers’s glider was among those that crashed. He sustained multiple injuries and was soon evacuated back to the United Kingdom.

On June 10, 1944, Lieutenant Myers arrived at 4112 U.S. Army Hospital Plant (228th Station Hospital) at Sherborne, Dorset, England. The following day, he was transferred to 4173 U.S. Army Hospital Plant (90th General Hospital) at Malvern Wells, Worcestershire, England.

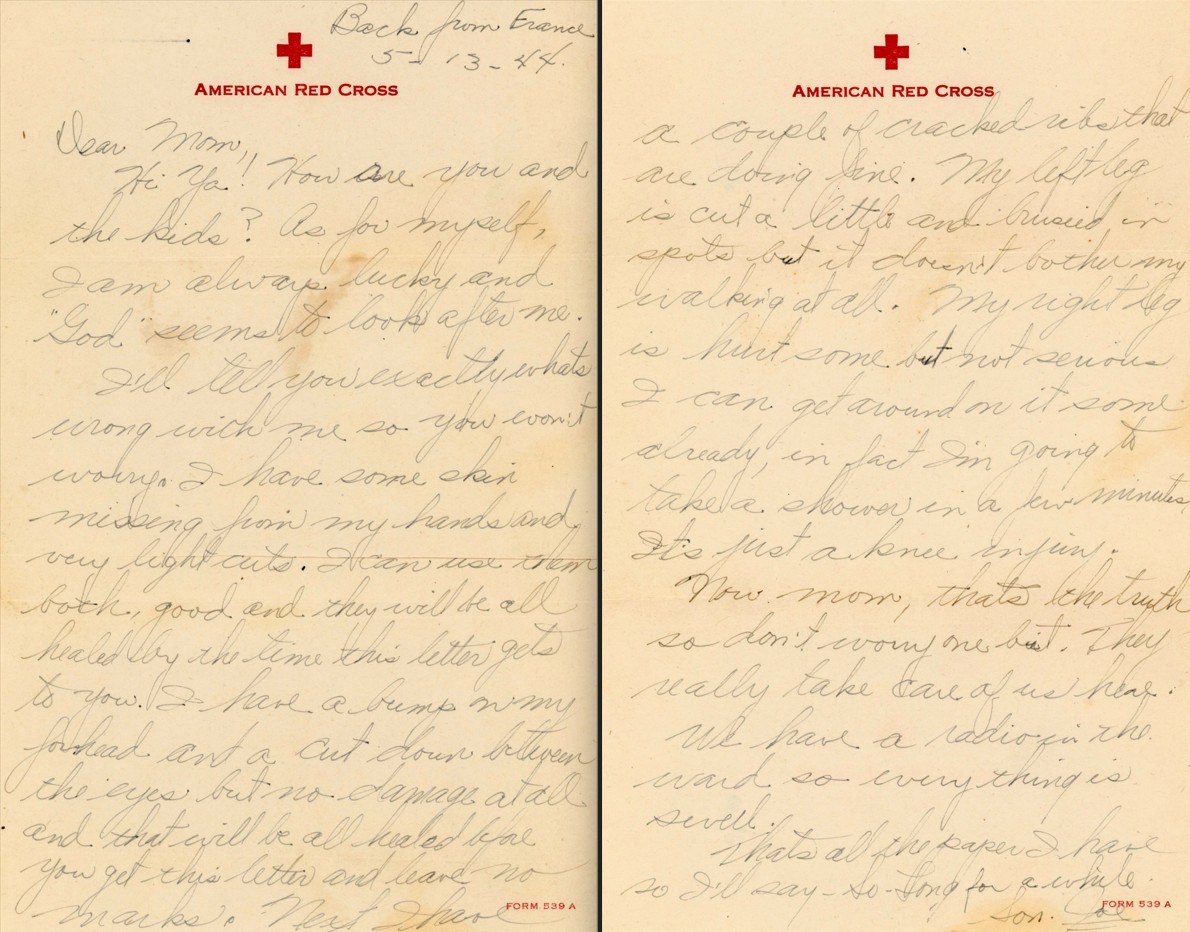

In a letter to his mother written from the hospital—he dated it May 13, 1944, but it was more likely written around June 13—Myers took a cheerful tone, writing in part: “I am always lucky and ‘God’ seems to look after me.” He described his injuries:

I’ll tell you exactly what’s wrong with me so you won’t worry. I have some skin missing from my hands and very light cuts. I can use them both, good and they will be all healed by the time this letter gets to you. I have a bump on my forehead and a cut down between the eyes but no damage at all and that will be all healed before you get this letter and leave no marks. Next I have a couple of cracked ribs that are doing fine. My left leg is cut a little and bruised in spots but if doesn’t bother my walking at all. My right leg is hurt some but not serious. I can get around on it some already, in fact I’m going to take a shower in a few minutes. It’s just a knee injury.

Now mom, that’s the truth so don’t worry one bit. They really take care of us here. We have a radio in the ward so everything is swell.

Lieutenant Myers was awarded the Purple Heart per General Orders No. 7, Headquarters 90th General Hospital, dated July 8, 1944. On July 21, 1944, he transferred to the Detachment of Patients, 4168 U.S. Army Hospital Plant in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, England.

Journal-Every Evening reported on July 28, 1944:

Painfully injured in the invasion of France on D-Day, Lieutenant Myers writes that he is recovering nicely and hopes to be able to rejoin his old outfit soon. He was a Ranger, one of the specially trained assault units. […]

One of his brothers, Private Orville Myers is with the transportation corps in Louisiana. Another brother, William Myers, was recently given a medical discharge and is helping on the farm. A brother-in-law, Wilton [Virdin], is serving in the Pacific area.

Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry Regiment took heavy casualties in Normandy, with an assault across a well-defended causeway at La Fière, France, on the morning of June 9, 1944, being particularly costly. The casualties included all five company officers. In addition to Lieutenant Myers being injured on landing, during the campaign both rifle platoon leaders as well as the company’s executive officer were killed, and the company commander was wounded.

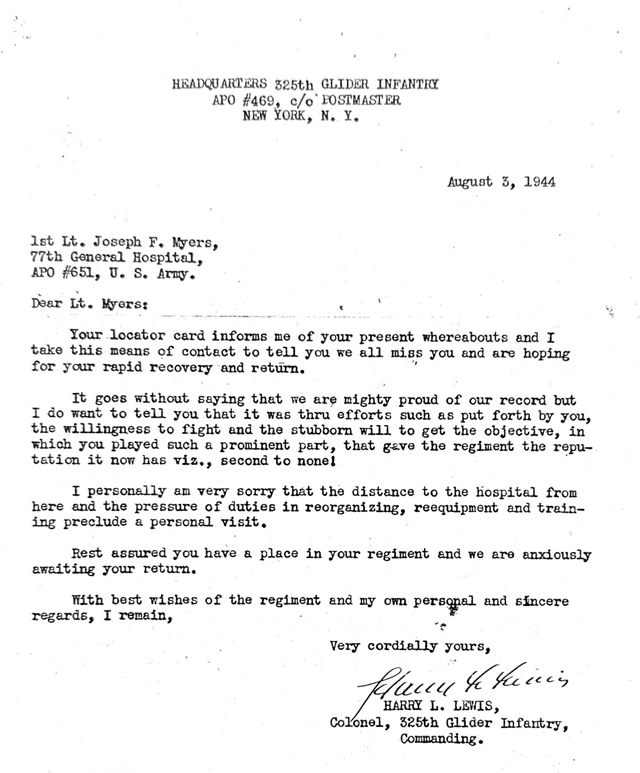

On August 3, 1944, the 325th Glider Infantry’s commanding officer, Colonel Harry L. Lewis (1891–1945), wrote Myers a letter, a copy of which is preserved in his R-file (reconstructed file, after his original personnel files were destroyed in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire). Its upbeat tone belied both the regiment’s heavy losses as well as the fact that Colonel Lewis was dying of cancer and would soon be returning to the United States. He stated in part:

Your locator card informs me of your present whereabouts and I take this means of contact to tell you we all miss you and are hoping for your rapid recovery and return.

It goes without saying that we are mighty proud of our record but I do want to tell you that it was thru efforts such as put forth by you, the willingness to fight and the stubborn will to get the objective, in which you played such a prominent part, that gave the regiment the reputation it now has viz., second to none! […]

Rest assured you have a place in your regiment and we are anxiously awaiting your return.

Combat in the Netherlands

According to his mother’s statement, Lieutenant Myers was hospitalized until September 5, 1944, just under three months following his injury. A morning report confirms that Myers rejoined Company “G” the following day. The summer of 1944 had seen the Allies break out of Normandy and liberate most of France. To capitalize on the apparent rout of the German military, the Allied planners conceived of Operation Market Garden, the largest and arguably the boldest airborne operation ever executed. The plan was for airborne forces seize bridges over rivers and canals in the Netherlands, securing a route for ground forces to thrust into Germany. Available Allied troop carrier aircraft were insufficient to deliver the two American airborne divisions and one British airborne division (plus a Polish parachute brigade) in a single lift on the first day of the operation, September 17, 1944.

The 325th Glider Infantry, with Lieutenant Myers’s 2nd Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry attached, had originally been scheduled to arrive on D+1, but the weather in England kept them grounded for nearly a week. Despite the tremendous courage and sacrifices by Allied soldiers and Dutch civilians, Operation Market Garden had already failed by the time the 325th got back into action. The last British paratroopers holding one end of the final bridge over the Rhine at Arnhem were overwhelmed on September 21, 1944. Fighting continued as the Germans tried to sever the corridor through the Netherlands, threatening Allied forces along the route with encirclement. On September 23, 1944, the seventh day of the operation, Myers’s battalion and the rest of the 325th Glider Infantry, finally arrived. The following day, they relieved the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment near Groesbeek, just west of the German border.

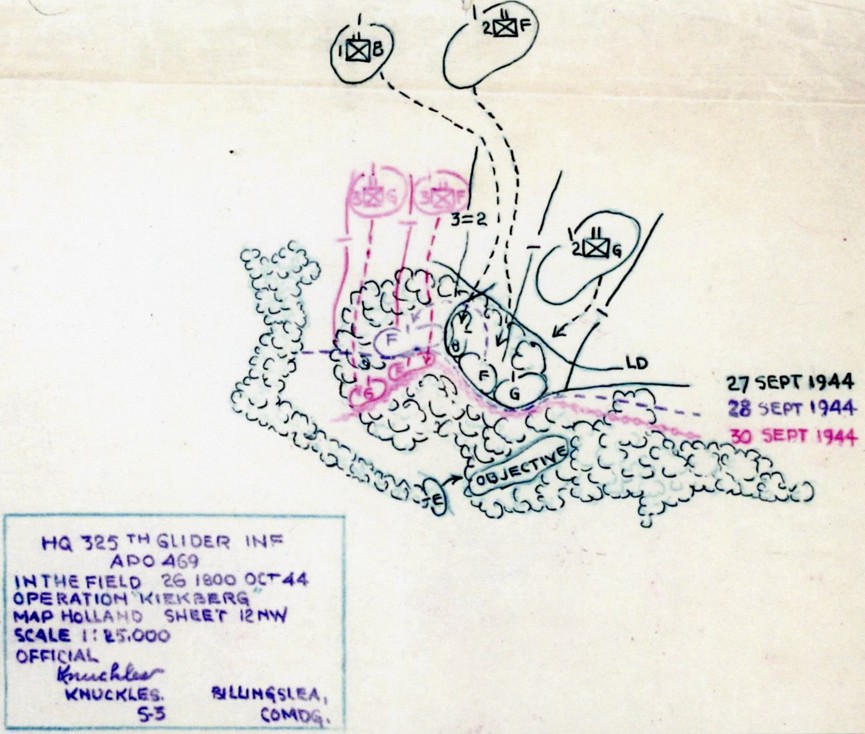

The regimental after action report stated that the 325th Glider Infantry soon identified a German salient in a wooded area south of Groesbeek as its most pressing concern:

The 2nd Bn had a problem that daily took on a more important aspect. Sticking up in the center of its position like a sore thumb was the Kiekberg forest, a veritable jungle about 1200 yards wide and more than 1700 yards long. All efforts of patrols to “feel out” this rugged bit of terrain were repulsed by the enemy almost before they started.

Daily the enemy was increasing his forces and strengthening his positions. Every bit of information indicated that he would soon be ready to launch an attack from this stronghold. It was a situation that called for aggressive and immediate action. The problem that faced the regiment was not a simple one: How to defend a front of 1100 yards and still release enough troops to attack this fortress.

In his book, All American, All the Way, Phil Nordyke wrote:

The Germans had fortified the woods with over thirty machine guns strategically positioned, supported by lots of infantry to cover the gaps. The positions were well camouflaged in the thick undergrowth. The Germans would wait until the attackers came to within a few yards of their hidden positions and then open fire from the front and flanks.

Beginning at 0545 hours on the morning of September 27, 1944, two companies from 2nd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry, with a company from 1st Battalion acting as a reserve, “pushed methodically against stiffening resistance until about 1000 a.m., securing a wedge into the woods about 500 yards deep and 800 yards wide.” The following day, one company made some progress with a flanking maneuver, but the other two made no headway.

On September 29, 1944, Companies “F” and “G” of the 401st Glider Infantry Regiment were relieved by the 505th Parachute Infantry to make them available for a fresh push on the Kiekberg forest. They moved into position that night.

At 0750 hours on September 30, 1944, Allied artillery began a seven-minute-long barrage of the German positions. Then at 0800, Companies “F” and “G” of the 401st jumped off on the attack, supported by Company “G” of the 325th. The 325th Glider Infantry after action report stated that in three hours, the men of the 401st “had pushed ahead between 500 and 800 yards” in the face of heavy German artillery and mortar fire.

According to a medal citation, during the attack, Lieutenant Myers “personally led his machine gun section which had the assignment of giving supporting fire to the advance of the 1st and 2nd rifle platoons.”

As they moved through the dense forest, Myers and his men stumbled upon “An enemy pocket of resistance consisting of five men armed with a machine gun, machine pistols, and grenades surprised Lieutenant MYERS and five men near him by tossing” two grenades. The first was off the mark, but the second landed right in the middle of the Americans.

Myers screamed, “Grenade, duck!” Those were his last known words.

The citation continued:

Realizing that the entire group might be killed or wounded, he without hesitancy threw himself upon the grenade in an attempt to protect his men. The exploding grenade mortally wounded Lieutenant MYERS, but his men escaped injury. This demonstration of willingness to make the supreme sacrifice that others might live to fight for a just cause reflects the highest traditions of the Army of the United States.

The 325th Glider Infantry report stated that after the American advance through the forest ground to a halt, there was a lull in the fighting “for about an hour while rival battalion commanders attempted to talk the other into surrendering. The debate ended in a draw and half an hour later fighting was resumed.”

Despite the day’s progress, the 82nd Airborne Division was notified that “A large scale German counterattack with two divisions of infantry supported by tanks was expected in the divisional sector that same night[.]” To withstand the counterattack, there was no choice but to “straighten the defensive line in the woods” meaning that about “3500 squar[e] yards of jungle bought at a high price had to be abandoned.”

Although several soldiers had witnessed his death, in the absence of a body, Lieutenant Myers was held as missing in action for the next six weeks.

The American withdrawal from the Kiekberg woods may have contributed to a mystery which has haunted the Myers family for over 80 years. Graves registration personnel later located several American soldiers in isolated graves in the forest, but Lieutenant Myers’s body was never located, or was never positively identified.

During World War II and in subsequent conflicts, several Americans were decorated with the nation’s highest award, the Medal of Honor, for sacrificing their lives by falling on a grenade to save their comrades. However, on November 11, 1944, the same day his status was changed to killed in action, 1st Lieutenant Myers was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, second in precedence to the Medal of Honor. Myers was also awarded an oak leaf cluster in lieu of a second Purple Heart.

During his career, 1st Lieutenant Myers earned the Distinguished Service Cross, the Purple Heart with one oak leaf cluster, the American Defense Service Medal, and the Combat Infantryman Badge (C.I.B.). According to his R-file, he also earned a Dutch award, the Military Order of William, as well as the Bronze Star Medal (B.S.M.). The latter was due to a postwar decision that anyone who had earned the C.I.B. during World War II had met the criteria for the B.S.M.

1st Lieutenant Myers is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at the Netherlands American Cemetery, and at several locations in Delaware: a cenotaph at Odd Fellows Cemetery in Camden, a plaque dedicated to local World War II fallen in Dover, and at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Notes

1930 Census

Oddly, Myers was recorded as Daniel Myers on the 1930 census.

Move to Delaware

The exact date the Myers family moved to Delaware is unclear, though it was most likely after June 28, 1938, when Myers graduated from Hartwick High School. Myers’s father’s death certificate stated that the family moved to Magnolia, Delaware, around 1939, while a property deed indicated that they were already residents of Kent County, Delaware, prior to March 18, 1939.

Magnolia or Frederica?

Although different documents describe Myers as having lived in Magnolia or Frederica between 1939 and 1941, it is unclear whether he moved during that time. Contemporary newspapers described him as a resident of Magnolia, while military documents and his mother’s statement described him as being from Frederica. The family farm was outside both small towns along the highway between Frederica and Dover, which passes through Magnolia.

Enlisted Service Number

Occasionally, duplicate service numbers were issued, including Myers’s enlisted one, 32065351. An enlistment data card, U.S. Navy passenger list, and morning reports confirm that the same service number was issued to a John H. Salle (1916–1986) who was inducted into the U.S. Army in Newark, New Jersey, on April 8, 1941, a few months after Myers. Both Trenton and Newark handled inductees from the Second Corps Area (Delaware, New Jersey, and New York). Quite a few men inducted at Trenton in January 1941 had their service numbers duplicated at Newark that April.

December 1942

2nd Lieutenant Myers’s movements in December 1942 are unclear prior to joining Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry. He began the month attached to his O.C.S. unit, 31st Company, 2nd Student Training Regiment. Unfortunately, the company’s morning reports for the month went missing before they could be microfilmed.

U.S. Army Hospital Plants

In 1944, various hospital buildings in the European Theater were designated as numbered U.S. Army hospital plants. Patients dropped from their previous organizations due to illness or wounds were assigned to the detachment of patients for the hospital plant, whereas previously they had been assigned to the detachment of patients for a particular medical unit (e.g., 228th Station Hospital). Patients at a plant were treated by the medical personnel who were members of one or more hospital units operating at that hospital plant. Even if the medical unit moved, the hospital plant designation remained unchanged for the facility.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Lieutenant Myers’s great-niece, Erin Hevesi, and the Myers family, as well as to Dorsey Wilkin and Phil Nordyke, for contributing information, photos, and documents. Thanks also go out to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“325th Glider Infantry Plays Important Role in Historic Operation.” Undated, c. November 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Briscoe, Charles H. “Commando & Ranger Training Part II, Preparing America’s Soldiers for War: The Second U.S. Army Ranger School & Division Programs.” Veritas, 2016 (Volume 12, No. 1). https://arsof-history.org/pdf/v12n1.pdf

Census Record for Daniel [sic] Myers. April 9, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRHB-DSY

Census Record for Joseph Myers. January 22, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRXN-WJ7

Census Record for Joseph Myers. May 6, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MR-M3X

Certificate of Death for Daniel F. Myers. March 1942. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DR63-ZXZ, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMB-L9M1-C

“Convoy UT.2” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/misc/index.html?yy.php?convoy=UT.2!~miscmain

“Convoy UT.3” Arnold Hague Convoy Database. http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/misc/index.html?yy.php?convoy=UT.3!~miscmain

Deed Between Kent Real Estate Corporation, Party of the First Part, and Daniel F. Myers and Hattie Lucille Myers, Parties of the Second Part. March 18, 1939. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 3555-000-021, Recorder of Deeds, Kent County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_222003-00415

“Dorothy ‘Dottie’ Coverdale Curl.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/107485820/dorothy-curl

“Draft Boards Making Plans For New Lists.” Journal-Every Evening, January 3, 1941. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140719204/

Draft Registration Card for Joseph Foss Myers. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-X8Z1

Enlistment Record for John H. Salle. April 8, 1941. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32065351&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=2801173

“General Orders Number 7, Headquarters 90th General Hospital.” July 8, 1944. Army General Orders, 1940–1957. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/333187305/004/333187305_0441/333187305_0441.pdf

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Joseph F. Myers. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Kemp, Al. “Memory of World War II hero still shines.” Delaware State News, May 25, 2009.

“Magnolia Veteran of 2 Glider Campaigns Is Instructor Now.” Journal-Every Evening, May 22, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140722075/

Morning Reports 31st Company, 2nd Student Training Regiment. August 1942 – November 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2780/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2780-20.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry Regiment. August 1943 – June 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-08/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0170B/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0170B-13.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-08/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0460/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0460-05.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-08/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0460/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0460-06.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0416/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0416-20.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0659/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0659-17.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-10/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0549/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0549-24.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0675/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0675-14.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-12/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0541/85713825_1943-12_Roll-0541-18.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-01/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0624/85713825_1944-01_Roll-0624-29.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-02/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0610/85713825_1944-02_Roll-0610-24.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-03/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0653/85713825_1944-03_Roll-0653-20.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-04/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0661/85713825_1944-04_Roll-0661-34.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-05/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0736/85713825_1944-05_Roll-0736-15.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-06/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0567/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0567-35.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry Regiment. December 1942 – April 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1941/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1941-01.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1941/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1941-02.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry Regiment. June 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1941/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1941-02.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “G,” 401st Glider Infantry Regiment. September 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Phil Nordyke.

Morning Reports for Company “H,” 1229th Reception Center. January 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2851/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2851-05.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “I,” 71st Infantry Regiment. January 1941 – September 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660-01.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660-02.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660-03.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1660-04.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment of Patients, 4112 U.S. Army Hospital Plant. June 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-06/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0421/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0421-22.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment of Patients, 4168 U.S. Army Hospital Plant. July 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-07/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0680/85713825_1944-07_Roll-0680-19.pdf

Morning Reports for Detachment of Patients, 4173 U.S. Army Hospital Plant. June 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1944-06/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0571-Dup/85713825_1944-06_Roll-0571-Dup-19.pdf

Morning Reports for Headquarters Company, 71st Infantry Regiment. April 1942 – May 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1656/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1656-35.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1656/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1656-36.pdf

Morning Reports for Headquarters Detachment, 3rd Battalion, 71st Infantry Regiment. November 1941 – December 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1657/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1657-22.pdf

Morning Reports for Service Company, Second Army Ranger School. January 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2873/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2873-26.pdf

Myers, Joseph F. Letter to Lucille Myers. January 4, 1944. Courtesy of Erin Hevesi and the Myers family.

Myers, Joseph F. Letter to Lucille Myers. Misdated May 13, 1944, correct date c. June 13, 1944. Courtesy of Erin Hevesi and the Myers family.

Myers, Lucille. Individual Military Service Record for Joseph Foss Myers. Undated, c. February 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20104/rec/1

Nordyke, Phil. All American All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II. Zenith Press, 2005.

Official Military Personnel File for Joseph F. Myers. Official Military Personnel Files, 1912–1998. Record Group 319, Records of the Army Staff. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Posthumous Award of Medals To State Men to Be Broadcast.” Journal-Every Evening, March 23, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/108433221/

“Regimental History, 325th Glider Infantry The Normandy Campaign 6 Jun 44 – 14 Jul 44.” Undated, c. July 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Report of Induction for Joseph Foss Myers. January 7, 1941. Courtesy of Erin Hevesi and the Myers family.

Report of Physical Examination for Joseph F. Myers. June 29, 1942. Courtesy of Erin Hevesi and the Myers family.

“Robert Lee (Bob) Myers.” Visalia Times-Delta, April 28, 2010. https://www.newspapers.com/article/162565821/

“Two Delaware Soldiers Give Lives Overseas.” Journal-Every Evening, July 28, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/140719470/

West, Andrew. “Caretaker honors heroes.” Delaware State News, May 25, 2008.

Last updated on July 16, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.

What an excellent biography of a true hero!

LikeLike