| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Tack welder for Pusey & Jones Corporation |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32367674 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Medical Detachment, 133rd Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Naples-Foggia campaign |

Early Life & Family

Everett William Adkins was born in Wilmington, Delaware, on March 6 or 7, 1920. He was sixth child of Harry Fisher Adkins, Sr. (a laborer, 1875–1949) and Dolly Martha Adkins (née Hoverter, 1885–1941). His parents were residents of 1122 B Street in Wilmington at the time. Adkins had four older sisters, an older brother, and a younger sister. He also grew up with an older half-sister from his mother’s first marriage. Adkins was Protestant.

Sometime between February 23, 1922, and September 3, 1926, the Adkins family moved to 919 Bennett Street in Wilmington. They were recorded at the same address on the next census in April 1930. In an affidavit dated April 7, 1944, Adkins’s sister, Naomi M. Adkins (later Citro, 1918–1989), stated that their father had abandoned the family 15 years earlier, though that figure might be slightly off if the 1930 census was accurate.

Adkins attended the Bancroft School in Wilmington until March 1935, dropping out after completing the 7th grade. He was a member of the local Young Men’s Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.).

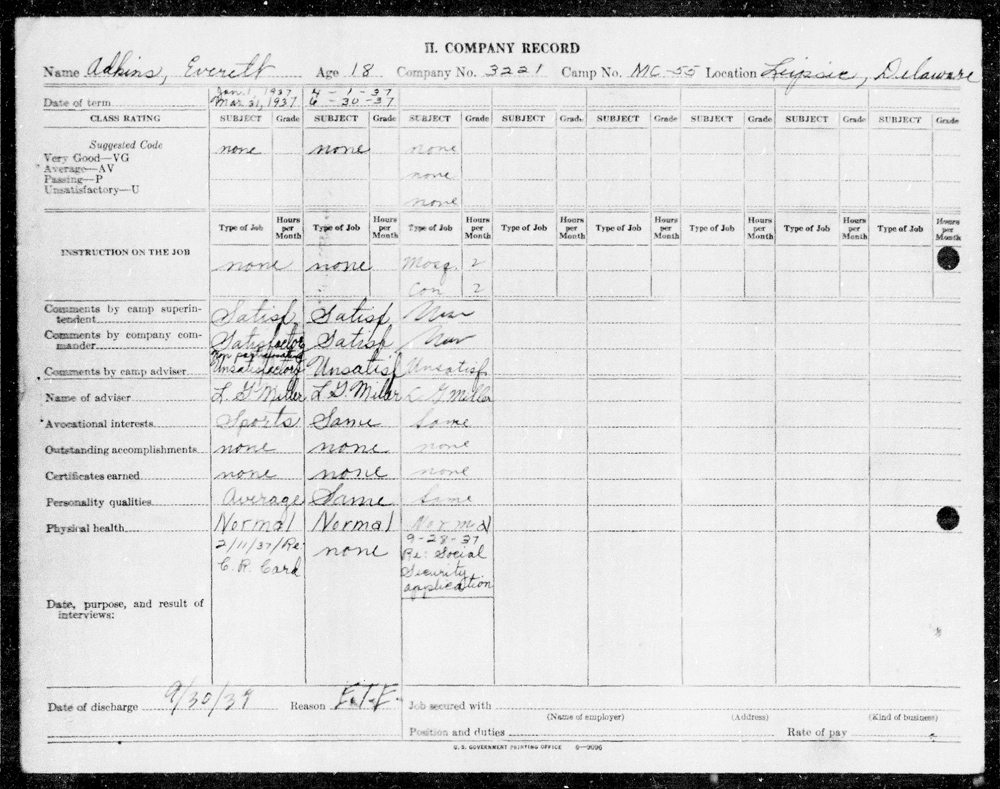

By the spring of 1936, in the middle of the Great Depression, Adkins was living with his family at 908 Spruce Street in Wilmington. On March 22, 1936, Adkins applied to join the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.). He reported that he had worked six months as a truck helper but had been unemployed since June 1935, adding that he wanted to find a job as a coal truck driver after leaving the organization. On April 14, 1936, he officially enrolled in the C.C.C. and committed to serve until at least September 30, 1936. He was assigned to Company No. 3221 at Camp MC-55 in Leipsic, Delaware. His enrollment paperwork described Adkins as standing five feet, eight inches tall and weighing 130 lbs., with brown hair and gray eyes.

The C.C.C. was administered by U.S. Army personnel in a quasi-military fashion. Adkins compiled a satisfactory record doing mosquito control work, reenrolling on October 1, 1936, and again on April 1, 1937. His file noted he was absent without leave on June 10, 1936, and again on March 29, 1937, and that he was absent with leave during January 4–9, 1937, and May 17–22, 1937. At the end of his third enrollment, on September 30, 1937, Adkins was honorably discharged from the C.C.C. and provided transportation back to Wilmington.

Adkins was recorded on the census in April 1940 living with his mother, five siblings, and his nephew at 1347 Vandever Avenue in Wilmington. He was described as a laborer who had been out of work for six weeks leading up to April 1, 1940. Although his father was still living, his mother was listed as windowed, a common deception on census records of the era to avoid disclosing that a person was separated or divorced.

Adkins was living at the same address when he registered for the draft around March 1941. At that time, he was described as a tack welder for the Pusey & Jones Corporation who stood five feet, eight inches tall and weighed 140 lbs., with brown hair and blue eyes. The draft registration card indicated that he moved several times to different Wilmington addresses prior to entering the service. If accurate, he moved from 1347 Vandever Avenue to 718 East 22nd Street, followed by 615th West 8th Street, and finally 409 East 4th Street. However, his sister, Dorothy Kirby (later Walls, 1910–1993), told the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission that her brother was living at 300 East 4th Street when he entered the service.

Shortly after Adkins registered for the draft, a day of joy for his family was marred by tragedy. Journal-Every Evening reported that on June 14, 1941, Dolly Adkins “collapsed as she was leaving the rectory of St. Patrick’s Church after witnessing the marriage of her daughter, Miss Ruth Adkins, and Claude McCartney.” She died while being transported to the hospital.

Soon after losing their mother, Adkins and his siblings found that their estranged father had resorted to a new tactic to involve himself in their lives. In early 1942, Adkins’s father sued his seven adult children in the New Castle Court of Common Pleas, claiming that was “unable to earn a sufficient sum to provide for his necessities” and “has often requested his said children to contribute to his support, but they have refused and neglected so to do.” At the time the suit was filed, Everett Adkins was described as living at 615 West 8th Street with four of his siblings. On February 17, 1942, Judge Leonard Wales ordered Everett Adkins and his eldest brother, Harry Adkins, Jr. (1914–1976), to each pay their father $3.50 per week, but let the other Adkins children off the hook.

When Adkins entered the service later that year, he failed to mention his father when filling out his paperwork, instead listing his sister, Gladys T. Adkins (later Lisowski, 1912–1991), as his emergency addressee and beneficiary, with Naomi Adkins as contingent beneficiary.

Military Training & Overseas Service

After he was drafted, Adkins was inducted into the U.S. Army at Camden, New Jersey, on October 22, 1942. As was customary for selectees, he was briefly transferred to the Enlisted Reserve Corps (E.R.C.) on inactive duty. He was recalled to duty on November 5, 1942, and attached to Company “M,” 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey.

Private Adkins trained at the Medical Replacement Training Center, Camp Pickett, Virginia. Per Special Orders No. 17, Headquarters Medical Replacement Training Center, Camp Pickett, Virginia, dated January 20, 1943, he was transferred to the 78th Infantry Division—at the time, a replacement pool division—at Camp Butner, North Carolina. On January 28, 1943, Private Adkins was assigned to Company “B,” 303rd Medical Battalion, 78th Infantry Division. On February 25, 1943, he transferred out of the unit, arriving three days later at the Shenango Personnel Replacement Depot, Pennsylvania. On March 1, 1943, he was attached unassigned to Company “A,” 12th Training Battalion, 3rd Training Regiment. His military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) code was listed as 521, basic, indicating that he had not yet qualified in an M.O.S. Despite the name, the unit appears to have been less a training unit than a placeholder for replacements before they went overseas.

A payroll entry indicates that Private Adkins went overseas on April 22, 1943. On May 12, 1943, he was transferred to the Medical Detachment, 133rd Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division, per Special Orders No. 67, Headquarters 34th Infantry Division. Adkins joined the 34th Infantry Division at the very end of the Tunisian campaign. Following the Allied capture of the major port cities of Tunis and Bizerte on May 7, 1943, Axis forces in North Africa were cut off from the possibility of resupply or evacuation and began to surrender. The campaign, a major victory for the Allies, officially ended on May 13, 1943.

Adkins was promoted to private 1st class on August 1, 1943. A document in Adkins’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) suggests he was attached to 3rd Battalion, 133rd Infantry. It is unknown if he was a medic attached to an infantry platoon, a litter bearer responsible for evacuating casualties, or performed some other duty.

Naples-Foggia Campaign

The 34th Infantry Division was not involved in the invasion of Sicily, nor in the initial stages of the invasion of mainland Italy. Most of the 133rd Infantry Combat Team arrived at Salerno, Italy, on September 22, 1943, 13 days after the beginning of Operation Avalanche. 2nd Battalion, 133rd Infantry had been temporarily detached in North Africa and the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate), a largely Nisei unit, was attached as a substitute.

The 133rd Infantry soon joined the push to the north up the peninsula. During October 1943, the regiment participated in capturing Benevento and, after delays caused by miserable weather, helped secure two bridgeheads over the Volturno. With its crescent shaped path, the river obstructed the division’s path several times. According to a contemporary regimental history, the 133rd captured Ciorlano to end the month “and by noon of Nov 1st the 1st Bn had seized the remaining heights to their front overlooking the Volturno[.]”

Journal-Every Evening later reported: “In the last letter received from him by the family, Oct. 28, Private Adkins wrote that he expected to get a furlough home after the first of the year”—wishful thinking for someone who had only been overseas for six months—“and was sending $50 home for ‘spending money.’” Naomi Adkins later told the Army that she shipped her brother a wristwatch as a Christmas present, but there is no indication that he ever received it.

During October 1943, Medical Detachment, 133rd Infantry lost four men killed in action or died of wounds. In the Mediterranean and on the Western Front, German soldiers generally adhered to the Geneva Convention and did not intentionally target American medical personnel. However, medics were in the thick of the fighting and were only marginally safer than the infantrymen they accompanied. Initially, U.S. Army regulations specified only a single red cross brassard worn on the left arm. These provided protection from enemy riflemen and machine gunners only if the enemy could even see those markings under chaotic battlefield conditions. Many medics began to wear a second brassard and add red cross markings to their helmets, but even the best markings did not guarantee safety.

By their very nature, artillery and aircraft were far less discriminating than infantrymen. Properly marked aid stations and ambulances were not commonly targeted, but limitations of observation and the accuracy of munitions meant they were sometimes hit. Furthermore, even with the strictest adherence to Geneva Convention, to attack a position occupied by infantry or other legitimate targets inevitably meant endangering the medics accompanying them.

The 133rd Infantry Regiment would make its third assault across the Volturno on the night of November 3–4, 1943. A regimental history stated:

On Nov 3rd at an assembly of CO’s [commanding officers] & Staff at the Regimental C.P. [command post] the Regimental Commander explained in detail the attack to take place that night: The 3rd Bn to cross the river first with the town of S. Maria Oliveto as its objective, the 1st Bn to follow the 3rd and echelon to left after crossing and seize Hill 550 to the left of the 3rd Bn’s objective, the 100th to follow and take the low ground to the left and rear of the 1st Bn and protect the left flank and rear of the Division.

By 2319 hours on November 3, 1943, the 133rd Infantry was at the line of departure. A 30-minute artillery barrage was scheduled for 2330 hours to soften up enemy positions on the far side of the river, with 34th Infantry Division attack jumping off at midnight. The regimental history continued:

The Regiment moved out according to plan and at 0130 hours all three battalions were across the river. At 0845 hours 4 Nov all battalions reported being on their objectives. The 1st Bn reached their objective with only one casualty, the Bn Commander. Enemy resistance was strong consisting of machine-gun, mortar and artillery fire. Mines and booby-traps were so thickly strewn it was impossible to get vehicles across the river until the area had been cleared. Evacuation was possible at night only and then with difficulty due litter bearers having to pass over open flat terrain which was under enemy observation and harassing artillery fire. Casualties were heavy, appro[x]imately 116, [and] 26 prisoners were taken including one company commander and numerous enemy killed.

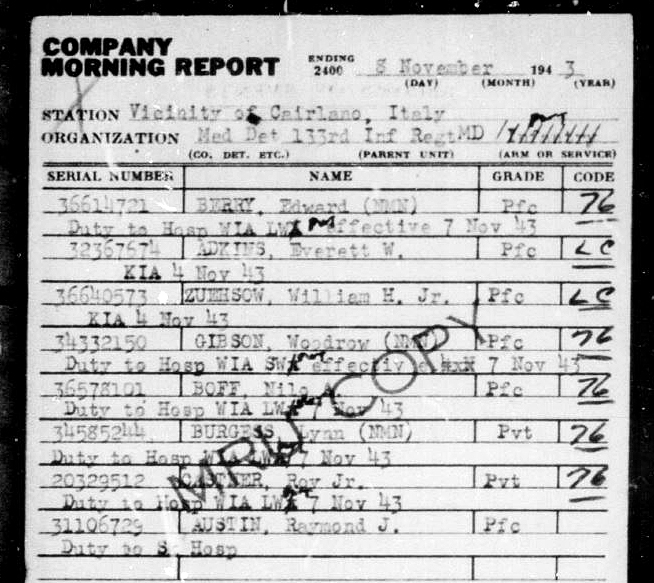

Private 1st Class Adkins was reported as killed in action on November 4, 1943, near Santa Maria Oliveto, Italy. His burial record stated that Adkins was struck in the chest and neck by artillery shell fragments and killed.

Adkins was one of four men from the regimental medical detachment to die that month. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

Adkins was initially buried at a temporary cemetery at Prata, Italy, on November 9, 1943. The following year, on November 1, 1944, he was reburied at another temporary military cemetery at Carano, Italy. Finally, on November 29, 1948, in accordance with the wishes of his sister, Gladys, that Adkins remain buried overseas, his casket was moved to a permanent cemetery at Nettuno, Italy, now known as the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery. His name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Birth Certificate & Date of Birth

Curiously, Adkins’s birth certificate inverted his first and middle names, listing him as William Everett Adkins. It also stated that he was born on March 6, 1920, at 4:30 p.m. All other known records list his date of birth as March 7, 1920, including his C.C.C. enrollment, draft card, and Adjutant General’s Office report of death.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Pat Greager and the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photos.

Bibliography

Batens, Alain S. and Major, Ben. “Identification of Medical Personnel, Vehicles and Installations.” WW2 US Medical Research Centre website. https://www.med-dept.com/articles/identification-of-medical-personnel-vehicles-and-installations/

Batens, Alain S. and Major, Ben. “The WW2 Medical Detachment Infantry Regiment.” WW2 US Medical Research Centre website. https://www.med-dept.com/articles/the-ww2-medical-detachment-infantry-regiment/

Census Record for Everett Adkins. April 10, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRH9-3S9

Census Record for Everett Adkins. April 16, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-M3S1

Certificate of Birth for Grace Marie Adkins. February 26, 1922. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DWBS-P98

Certificate of Birth for William Everett Adkins. March 12, 1920. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-696Q-2PS

Civilian Conservation Corps Record for Everett William Adkins. Individual Records (Enrollees), 1933–1943. Record Group 146, Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, 1871–2001. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/487119027?objectPage=1621

Draft Registration Card for Everett William Adkins. Undated, c. March 1941. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-XSY8

Enlistment Record for Everett W. Adkins. October 22, 1942. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&tf=F&q=32367674&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=2990308

“Harry Fisher Adkins.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/135296323/harry-fisher-adkins

Headstone Inscription and Interment Record for Everett W. Adkins. Headstone Inscription and Interment Records for U.S. Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942–1949. Record Group 117, Records of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1918–c. 1995. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/169008352?objectPage=376

“In the Matter of the Petition of Harry F. Adkins, a Poor Person, for Support.” January 1942 – February 1942. Court of Common Pleas, New Castel County, Civil Case Files, Civil Action Cases. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/105404/rec/1

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Everett W. Adkins. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Kirby, Dorothy P. Individual Military Service Record for Everett William Adkins. Undated, c. 1944. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/17488/rec/1

Marshall, Carley L. “History, 133rd Infantry Regiment 34th Infantry Division From 1 November 1943 to 30 November 1943 inc.” Undated, c. December 1943. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Marshall, Carley L. “History, 133rd Infantry Regiment 34th Infantry Division From 22 September 1943 to 31 October 1943, inclusive.” Undated, c. November 1943. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Morning Reports for 303rd Medical Battalion. January 1943 – February 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2070/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2070-30.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “M,” 1229th Reception Center. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2857/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2857-09.pdf

Morning Reports for Medical Detachment, 133rd Infantry Regiment. September 1943 – November 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0657/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0657-23.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0657/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0657-24.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-10/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0676/85713825_1943-10_Roll-0676-32.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-11/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0577/85713825_1943-11_Roll-0577-20.pdf

Morning Reports for Replacements, Company “A,” 12th Training Battalion, 3rd Training Regiment. March 1943 – April 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2883/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2883-05.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2883/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2883-06.pdf

“Mother Dies After Wedding.” Journal-Every Evening, June 16, 1941. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154248121/

“Naomi M. Adkins Citro.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/144538417/naomi-m-citro

“Pay Roll of Medical Detachment 133rd Infantry Regiment For month of August, 1943.” August 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1720/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1720_06.pdf

“Pay Roll of Medical Detachment 133rd Infantry Regiment For month of June, 1943.” June 30, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1720/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1720_06.pdf

“Pay Roll of Medical Detachment 133rd Infantry Regiment For month of November, 1943.” November 30, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/st-louis/rg-064/85713803_1940-1943/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1720/85713803_1940-1943_Roll-1720_06.pdf

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

The Story of the 34th Infantry Division: Louisiana to Pisa. Information and Education Section, Mediterranean Theater of Operations, United States Army, c. 1944. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/3983

“To New School.” The Evening Journal, September 3, 1926. https://www.newspapers.com/article/173677186/

“Wilmington Soldier Reported Killed Fighting Nazis in Italy.” Journal-Every Evening, December 15, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/154244818/

Last updated on June 11, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.