| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Shipfitters helper and statistical clerk |

| Branch | Service Number |

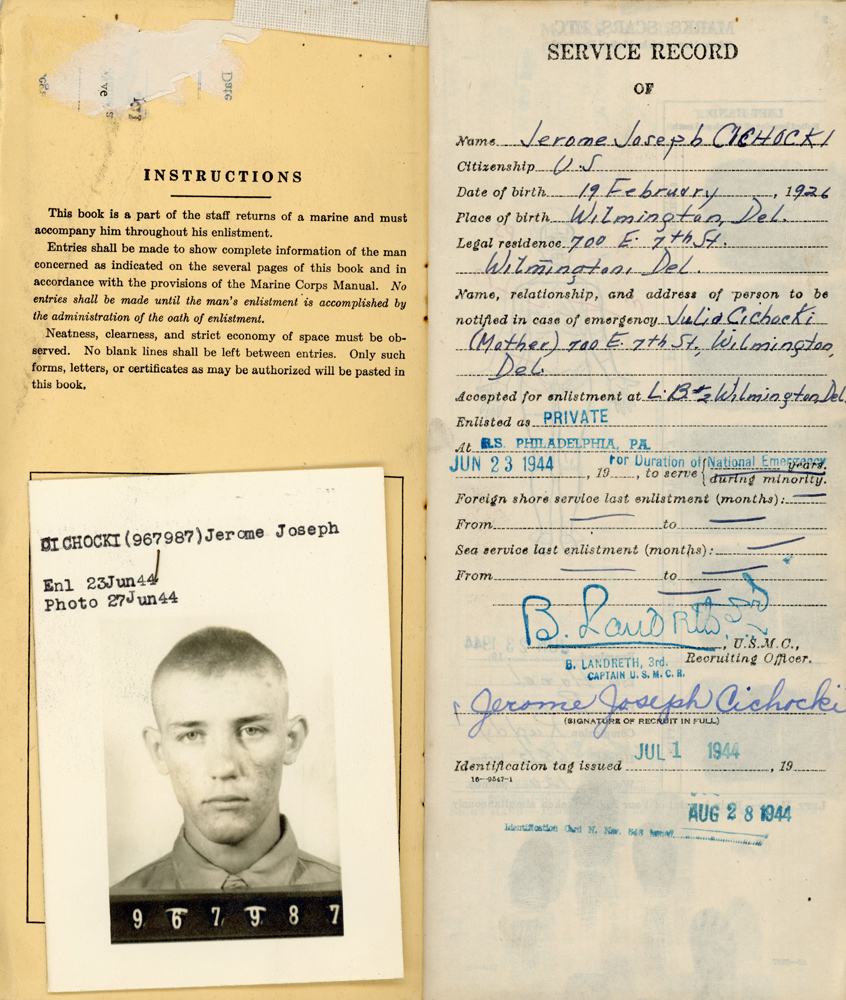

| U.S. Marine Corps Reserve | 967987 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Company “K,” 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines, 4th Marine Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 521 (basic) or 745 (rifleman) | Iwo Jima |

Early Life & Family

Jerome Joseph Cichocki was born in Wilmington, Delaware, on February 19, 1926. He was the son of Stanislaw Cichocki (Stanley Cichocki, a barber, c. 1884–1965) and Julianna Cichocki (Julia Cichocki, née Piorkowska, c. 1899–1972). Curiously, he was referred to as Herman Cichocki in the 1930 census and in his mother’s 1943 petition for naturalization, and as Harry Cichocki in the 1940 census. He had three older half-brothers and a half-sister from his mother’s first marriage, as well as two younger brothers. Available records suggest that Cichocki lived his entire life at 700 East 7th Street in Wilmington prior to entering the service. The row home, purchased by his father in 1917, is located one block west of Old Swedes Church.

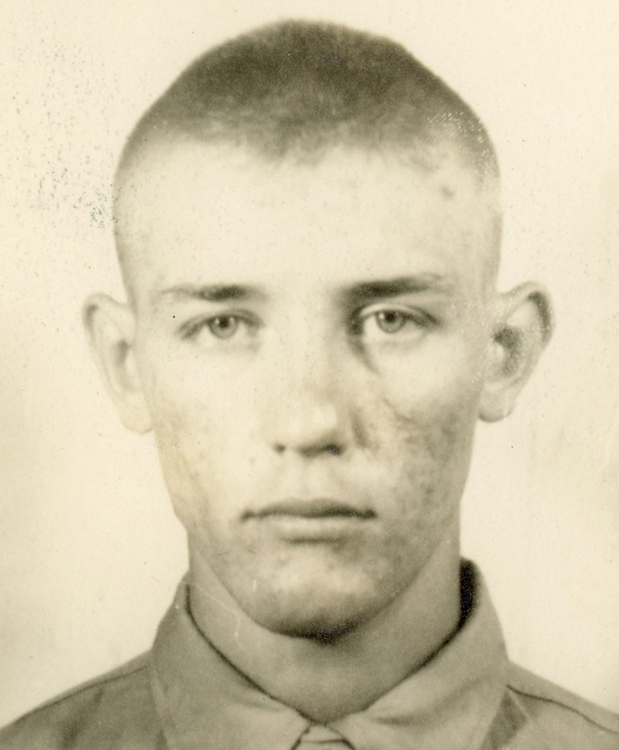

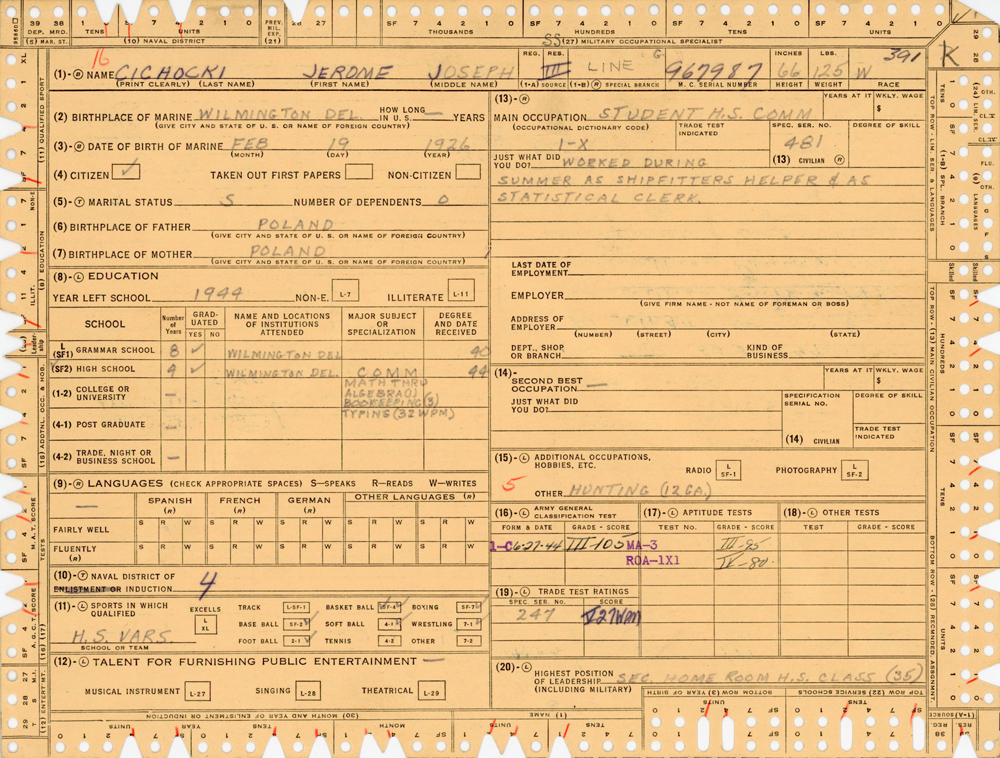

When Cichocki registered for the draft on his 18th birthday, February 19, 1944, the registrar described him as standing five feet, six inches tall and weighing 130 lbs., with blond hair and hazel eyes. Similarly, according to his Marine personnel file, Cichocki stood five feet, 5½ inches tall and weighed 126 lbs., with brown hair and hazel eyes. He was Catholic.

Cichocki attended the commercial course at Pierre S. duPont High School, which included algebra, bookkeeping, and typing. Journal-Every Evening reported that Cichocki, known to his teammates as Chick, “played on the junior varsity football team in 1941 and the varsity in 1942 and 1943. Weighing 130 pounds, he was the lightest weight boy ever to win a letter from the high school.” Historian Geoff Roecker notes that “‘Chick’ also was Marine slang for the youngest member of an outfit, and given Cichocki’s age and small stature I could believe that his civilian nickname followed him into the service.”

Cichocki told the Marine Corps that in addition to football, he played baseball, basketball, and softball, that he boxed and wrestled, and that he enjoyed hunting with a 12-guage shotgun. The Wilmington Morning News also reported that Cichocki “played with the St. Mary’s Cats baseball team, softball with the Paradise Athletic Club, and basketball on the Peoples Settlement team.”

Cichocki told the Marine Corps that during high school, he “worked during summer as shipfitters helper & as statistical clerk.”

Two of Cichocki’s half-brothers served in the military during the war: Frank A. Macuk (1922–1988) in the U.S. Navy and Stanley J. Macuk (1924–2002) in the U.S. Army Air Forces.

Military Training & Overseas Service

On March 18, 1944, while still in high school, Cichocki was classified as I-A by Wilmington Board No. 2. A doctor performed a physical exam on April 19, 1944, and found him qualified for military service.

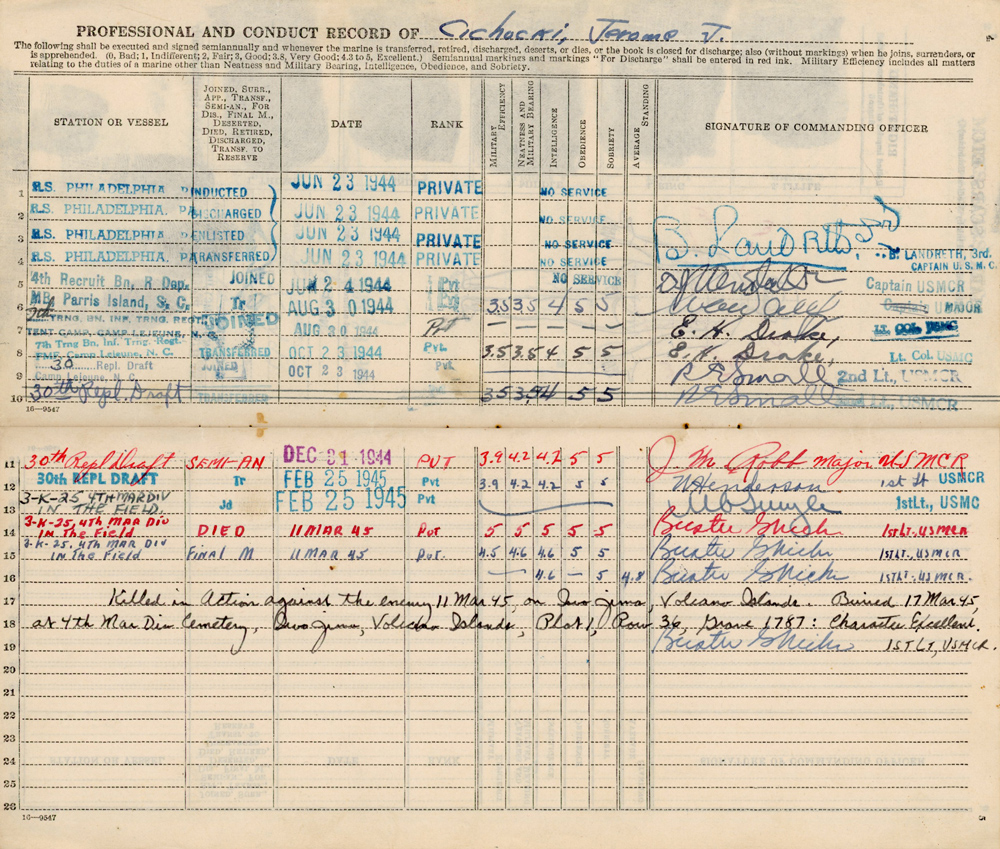

Shortly after graduating from Pierre S. duPont High School, Cichocki was drafted. He reported to the induction station in Camden, New Jersey, on June 23, 1944. Cichocki’s induction paperwork stated that he requested the U.S. Navy as his branch, but instead, he found himself crossing the Delaware River to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There he joined the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve for the duration of the war plus six months.

That same day, Private Cichocki and 37 other Marine recruits were dispatched to Parris Island, South Carolina, for boot camp. Although some members of this cohort were eventually assigned to the detachment aboard the battleship U.S.S. Texas (BB-35), many ended up going into combat on Iwo Jima about eight months later, where almost a third would become casualties.

On June 24, 1944, after an overnight train journey, Private Cichocki was assigned to the 4th Recruit Battalion at Parris Island. During his training, on August 8, 1944, he qualified at the sharpshooter level with the M1 Garand rifle, scoring 294 out of a possible 340. He also qualified as an expert with the bayonet on August 26. His personnel file also stated that he was instructed in the use of the hand grenade and familiarized with the M1 carbine, Reising submachine gun, and Browning Automatic Rifle.

After graduating from boot camp on August 30, 1944, Private Cichocki was transferred to the 7th Training Battalion, Infantry Training Regiment, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. He began a 10-day furlough on September 1, 1944. Evidently he misjudged the time it would take him to return to base, as he ended up absent over leave by four hours on September 11, 1944. His commanding officer levied a mild punishment: 15 hours of extra police duty. That is, he had to spend extra time cleaning or performing other menial tasks.

On October 23, 1944, Cichocki joined the 30th Replacement Draft, a holding unit similar to the U.S. Army’s replacement depots, although the replacement drafts went overseas together rather than as an unassigned shipment of personnel. On November 13, 1944, Cichocki boarded the transport U.S.S. General R. E. Callan (AP-139) at San Diego, California, shipping out the following day. After a brief stop in San Francisco, California, during November 15–16, the transport joined a convoy bound for the Pacific Theater. He went ashore at Kahului, Maui, Hawaii, on November 23, 1944.

The 30th Replacement Draft was attached to the 4th Marine Division to provide replacements for men who were killed, wounded, or sick. Many of the replacements received inadequate training before going into battle. John E. Lane, also a member of the 25th Marines, later recalled:

Battle replacements were recruits who had gone through Parris Island in the summer of 1944, where they had fired for qualification once. In early September, they were formed into an Infantry Training Unit at Camp Lejeune, where they went through “musketry range” once, threw one live grenade, fired one rifle grenade and went through one live-fire exercise. Designated the 30th Replacement Draft in October, they went to Camp Pendleton and straight on to Maui in Hawaii, where they worked on mess duties or working parties with no additional training. The day after Christmas Day they began boarding for Iwo Jima. Those who survived went back to Maui and began receiving the training that might have helped them before the operation.

On January 16, 1945, Private Cichocki boarded the attack transport U.S.S. Hinsdale (APA-120) at Kahului. After some training exercises, the transport returned to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on January 18. Hinsdale sailed west on January 27, 1945. Also aboard were men from the 25th Marines, 4th Marine Division, Private Cichocki’s eventual unit. The transport arrived at Eniwetok on February 5 and after refueling, sailed again for the Mariana Islands two days later. Hinsdale arrived at Saipan on the morning of February 11, 1945. After another amphibious exercise off Tinian during February 12–13, 1945—it is unclear if the men of the 30th Replacement Draft participated—the transport dropped anchor at Saipan.

Combat on Iwo Jima

Private Cichocki sailed from Saipan on the afternoon of February 16, 1945, aboard U.S.S. Hinsdale. The Battle of Iwo Jima began on his 19th birthday, February 19, 1945. He may have watched from the deck of the transport as his future unit hit the beach that morning. Coincidentally, his half-brother, Seaman 1st Class Frank A. Macuk, was nearby aboard the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Baltimore (CA-68), which escorted aircraft carriers supporting the operation.

It is unclear when Cichocki first set foot on the island. Though the men of the 30th Replacement Draft initially waited aboard transports offshore, it is possible that Cichocki landed on the island to join a work detail or wait in an assembly area prior to D+6, February 25, 1945, when he was transferred to Company “K,” 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines, 4th Marine Division.

Tenacious Japanese defenders hidden in caves and pillboxes forced the Marines to fight for every foot. American artillery fire, naval gunnery, and airpower was largely ineffective against Japanese fortifications, which had to be eliminated at close quarters by demolition squads armed with flamethrowers, bazooka rockets, and satchel charges. The 25th Marines had gone into division reserve on D+4, February 23.

Cichocki’s qualification card listed his military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) as 521, basic, suggesting he had not qualified in any M.O.S., though it listed the duty he performed in the 25th Marines as 745, rifleman.

Even for the best trained Marine, Iwo Jima was an unforgiving place to enter combat for the first time. Still, those who were already members of line units on February 19 entered combat on Iwo Jima with men they had at least trained intensely with, if not fought alongside. In contrast, replacements like Private Cichocki were doled out piecemeal, usually joining units in combat zones where they did not know anyone. A 25th Marines action report written after Iwo Jima complained:

When three or four men who have never seen each other previously are sent to a rifle squad, the original men in the squad have to spend a great deal of time finding out the capabilities of these men and the new men necessarily require several days to become adjusted to completely strange surroundings and to work with men they have never seen before.

In Cichocki’s case, there was at least one familiar face in Company “K.” Another replacement, Private Wallace Roscoe West, Jr. (1922–1945), a Delawarean in the same group of 38 men who had traveled together the previous June from Philadelphia to Parris Island, joined the company on the same day.

However much his new comrades may have wanted to train and acclimate Private Cichocki to the unit, there simply was not time. The 25th Marines went back into combat during the 4th Marine Division’s advance on the Motoyama plateau early the following morning on D+7, February 26, 1945. The Japanese defenses around Hill 382 were so strong that the Marines eventually began to refer to the area as the Meat Grinder. All three battalions of the 25th Marines deployed abreast, with 1st Battalion on the left, 2nd Battalion in the center, and Cichocki’s 3rd Battalion on the right, with 3rd Battalion of the 24th Marines attached as a reserve. The attack was preceded by heavy artillery fire and accompanied by tanks.

Jumping off around 0820 hours, the 25th Marines advanced about a football field before all hell broke loose. 1st and 2nd Battalions, advancing on the heavily defended terrain features nicknamed the Amphitheater and Turkey Knob, took the brunt of the Japanese machine gun and mortar fire. 3rd Battalion had a somewhat easier time advancing along the south coast of the island. Companies “L” and “I” were in the lead with Cichocki’s Company “K” in reserve. Company “I” on the right cleared the East Boat Basin. Company “K” followed Company “L,” demolishing any positions that potentially held bypassed Japanese soldiers.

In his postwar monograph, Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic, Lieutenant Colonel Whitman S. Bartley (1919–2010) wrote that Company “K” “cleaned up behind the advance and set elements to the left to cover the boundary where 2/25 [2nd Battalion, 25th Marines] lagged behind the more rapid advance of 3/25.” Depending on the source, 3rd Battalion gained between 300 and 500 yards that day. As was a common experience on Iwo, the battalion weathered a mortar barrage that evening and fended off Japanese infiltrators that night.

D+8, February 27, 1945, was a similar story, as Bartley wrote:

Company I secured the East Boat Basin and moved to high ground overlooking the Basin to tie in with Company L’s right flank. Companies L and K gained about 200 yards during the day, but held up when further advances would have made it difficult to maintain contact with the slower-moving 2d Battalion on the left.

D+9, February 28, 1945, was a frustrating day for the 25th Marines, with 1st Battalion forced to withdraw after a costly attack on Turkey Knob which claimed the life of another Delawarean from the group of 38 recruits, Private Ralph Outten Patterson (1925–1945). For a third day in a row, Cichocki’s 3rd Battalion faced the least resistance of any unit in the regiment, though with the difficult time 1st and 2nd Battalions were experiencing, 3rd Battalion could not advance more than 100 yards without exposing their flank. However, Cichocki and his comrades got little rest that night, with groups of Japanese infiltrators twice attempting to penetrate 3rd Battalion positions under cover of darkness.

On D+10, March 1, 1945, 2nd and 3rd Battalions were stationary while 1st Battalion was again repulsed from Turkey Knob. On the afternoon of D+11, though the Japanese still held Turkey Knob after another unsuccessful attack by 1st Battalion, 3rd Battalion managed to advance about 300 yards.

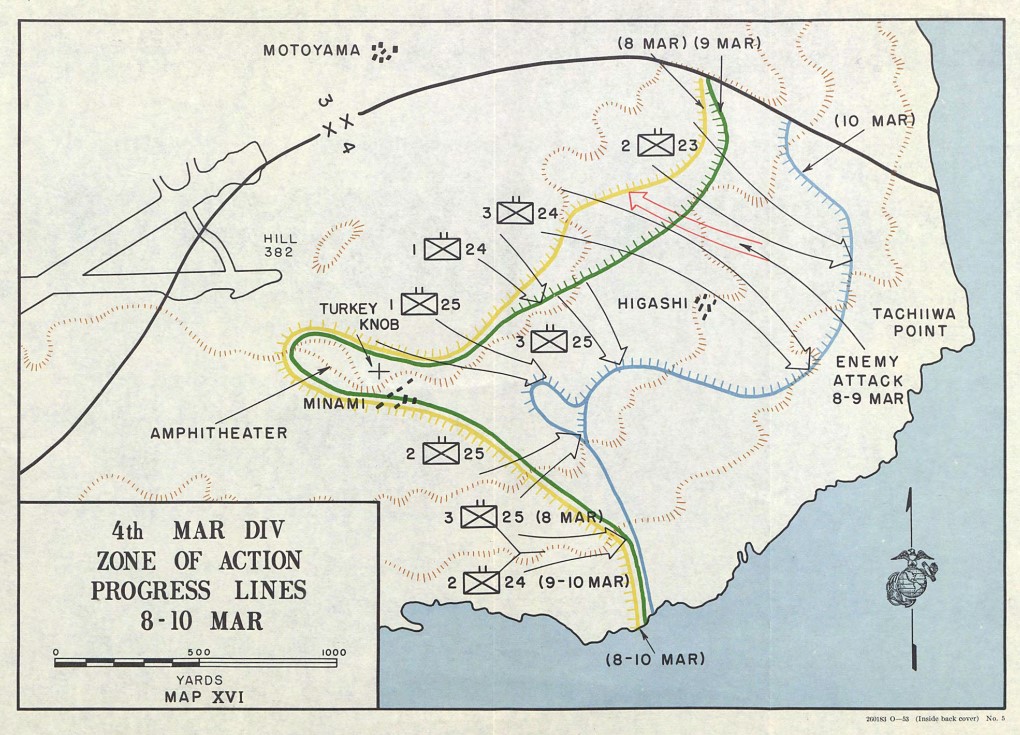

On D+12, March 3, 1945, the 23rd Marines relieved the exhausted 1st Battalion, 25th Marines, but 2nd and 3rd Battalions remained in place. On D+14, 1st Battalion returned to the line, though 3rd Battalion was reduced to two rifle companies when Company “L” was stripped to create a fourth provisional battalion, to assist in the reduction of what was now a Japanese salient around the Amphitheater and Turkey Knob. Unable to advance further until there was more headway to their left, by D+16, March 7, 1945, Bartley explained, Cichocki’s 3rd Battalion had spent

three days in strengthening its defenses to prevent a breakthrough by enemy troops during the anticipated 4th [Marine] Division drive southeastward to the coast. During this push the division’s left flank and center were to advance almost at a right angle to the front of 3/25, which tied into the coast about 1,000 yards east of the East Boat Basin. […] The attack would thus compress enemy troops into an area bounded by the sea and Marines holding the line on the south: in effect, a hammer and anvil, with the 25th Regiment now acting as the anvil.

They may have lacked the caves and pillboxes of the Japanese defenders, but 3rd Battalion built up enviable defenses including landmines, barbed wire, and 37 mm antitank guns loaded with canister rounds. A rare Japanese counterattack on the night of March 8–9 hit not the 25th Marines but the 23rd and 24th Marines. In the end, their extensive preparations did not benefit 3rd Battalion much, beyond the peace of mind that came with knowing that any infiltrators would have a harder time making it to their foxholes.

After nearly three weeks of fighting, the men of the 4th Marine Division had reduced the Japanese-held territory in their sector to a narrow strip on the east coast of Iwo Jima. During the month so far, 3rd Battalion had faced lighter opposition than the rest of the 25th Marines and casualties had been relatively light. However, Cichocki and the rest of the battalion were still under immense strain from regular mortar fire and nighttime infiltration attempts, as well as occasional close calls from friendly air, rocket, and naval fire. A contemporary 3rd Battalion narrative concluded that “All of this contributed to make our troops[,] a large percentage of which were inexperienced replacements, extremely ‘jittery’.”

On D+18, March 9, 1945, 3rd Battalion went into reserve and regained all its companies when the provisional battalion was disbanded. Wakeup time for 3rd Battalion the following morning, March 10, 1945, was 0430 hours. By 0600 they were back into the line, but not in the same familiar, well-fortified position along the coast. Instead, their new position was to the north and their orders were to attack. To use Bartley’s analogy, 3rd Battalion had shifted from being the anvil to being the hammer. At 0800 hours, the attack began with 3rd Battalion on the left and 1st Battalion on the right. Companies “K” and “I” were the 3rd Battalion assault companies with Company “L” in reserve. Despite Japanese opposition, the 25th Marines gained about 700 yards. The battalion muster roll recorded six men from Company “K” as killed in action or died of wounds that day.

On D+20, March 11, 1945, 3rd Battalion’s luck ran out, with Private Cichocki’s Company “K” being particularly hard hit. Cichocki was among the dead, suffering a fatal shell fragment wound to his chest. Private Wallace R. West, Jr.—who had entered the Marine Corps and joined Company “K” at the same time as Cichocki—was also killed that day.

The battalion report stated:

At 0730 the companies were ordered to move out and continue the attack. As it attempted to do so “K” Company was forced to come out into some open ground that afforded neither cover nor concealment. They were immediately met with a considerable volume of small arms fire from a high ridge to their left front quickly followed by heavy mortar fire that was believed to be coming from the general vicinity of [target square] 185 K. One platoon of “K” Company was completely wiped out as the result of a direct hit by a large type rocket. In fact so great were our casualties in the left sector of our zone of action that the CO of BLT 3/25 ordered an immediate reorganization consolidating “K” and “L” Companies into one company under the command of Lt. Morton of “K” Company.

The battalion muster roll listed 12 fatalities from Company “K” that day. Even though the company was already understrength, that figure suggests that claim that an entire platoon was “completely wiped out” by a single rocket was exaggerated. Regardless, D+20 was the single costliest day of March 1945 for the company.

Cichocki’s personal effects included letters, a religious medal, a belt, and a book. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

More Marines from Delaware died on Iwo Jima than during the Battles of Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Tinian, Guam, and Okinawa combined. Among Delawareans who died serving in the Marine Corps during World War II, 40% were killed on Iwo Jima. Of the group of 38 recruits who left Philadelphia together on June 23, 1944, the Battle of Iwo Jima claimed the lives of four, all of them Delawareans: Privates Cichocki, Patterson, West, and William Denny Veasey, Jr. (1922–1945). Another seven men were wounded and an eighth hospitalized with combat fatigue there, a total of 31.6% casualties among the group.

Private Cichocki was initially buried at the 4th Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima on March 17, 1945, the same day that the 25th Marines left the island.

Private Cichocki’s niece, Karen Hall, recalls being told: “When the military personnel came to the door to advise the family, it was my father”—Private Cichocki’s youngest brother, Raymond J. Cichocki (1930–2018)—“who had to break the news to his parents. Not something a 14 year old should have to do.” Journal-Every Evening reported Cichocki’s death on March 31, 1945.

In 1947, Private Cichocki’s mother requested that his body be repatriated to the United States. After his funeral at the Gornowski Funeral Home in Wilmington and requiem mass at St. Stanislaus Kostka Church, Cichocki was buried at Cathedral Cemetery. His parents and brothers were also buried there after their deaths.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Geoff Roecker, William Michels, and Private Cichocki’s niece, Karen Hall, for contributing information, documents, and photos.

Bibliography

Anderson-Colon, Jessica. “Marine Corps Boot Camp during World War II: The Gateway to the Corps’ Success at Iwo Jima.” Marine Corps History, Summer 2021. https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/MarineCorpsHistory_vol7no1_Summer2021_web2%20%281%29_1.pdf

“Annex How to Fourth Marine Division Operations Report Iwo Jima RCT 25 Report.” April 15, 1945. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/807/rec/1

Bartley, Whitman S. Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1954. https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/Iwo_Jima-_Amphibious_Epic.pdf

Beyer, E. F. “U.S.S. HINSDALE (APA-120) War Diary for February 1945.” March 26, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139968239?objectPage=4

Beyer, E. F. “U.S.S. HINSDALE (APA-120) War Diary for January 1945.” March 26, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139968239

Cichocki, Stanley. Individual Military Service Record for Jerome Joseph Cichocki. February 25, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18098/rec/1

Census Record for Harry Cichocki. April 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MR-MSJ2

Census Record for Herman Cichocki. April 14, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHM-GCJ

Draft Registration Card for Jerome Joseph Cichocki. February 19, 1944. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-XSKF-B

Hall, Karen. Email correspondence on March 9, 2025.

Indenture Between Powel Stolarski and Maryanna Stolarska, Parties of the First Part, and Stanislaw Cichocki, Part of the Second Part. April 21, 1917. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_256919-00596

“J. J. Cichocki Rites.” Wilmington Morning News, April 8, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/article/166802257/

“Marine Killed As Brother Comes Home.” Journal-Every Evening, March 31, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/165409995/

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps Headquarters, Third Battalion, Twenty Fifth Marines, Fourth Marine Division, From 1 March to 31 March, 1945, inclusive.” March 31, 1945. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/194974639?objectPage=820

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps Headquarters, Third Battalion, Twenty Fifth Marines, Fourth Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force, in the Field, From 1 February to 28 February, 1945, inclusive.” February 28, 1945. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/194961352?objectPage=1450

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps Headquarters, Thirtieth Replacement Draft, Fourth Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force, From 1 January to 31 January, 1945, inclusive.” January 31, 1945. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/194941965?objectPage=208

Official Military Personnel File for Jerome J. Cichocki. Official Military Personnel Files, 1905–1998. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Petition for Naturalization for Julianna Cichocki. June 21, 1943. Petitions for Naturalization, 1802–September 30, 1991. Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States. National Archives at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/470647468?objectPage=329

“Pvt. Jerome Joseph Cichocki.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/50481258/jerome_joseph-cichocki

Roecker, Geoffrey. “Replacements. Iwo JimaL 26 – 28 February, Pary II” The First Battalion, 24th Marines website. https://1-24thmarines.com/the-battles/iwo-jima/d8/

Starkey, R. C. “War Diary, USS GENERAL R. E. CALLAN (AP-139)—1 November 1944 to 30 November 1944.” November 30, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78694327

Wright, Derrick. Iwo Jima 1945: The Marines Raise the Flag on Mount Suribachi. Osprey Publishing, 2001.

Last updated on March 11, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.