| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Laundry extractor operator and locomotive oiler |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Marine Corps Reserve | 855406 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Company “I,” 9th Marines, 3rd Marine Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 745 (rifleman) or 746 (automatic rifleman) | Guam (patrols only), Iwo Jima |

Early Life & Family

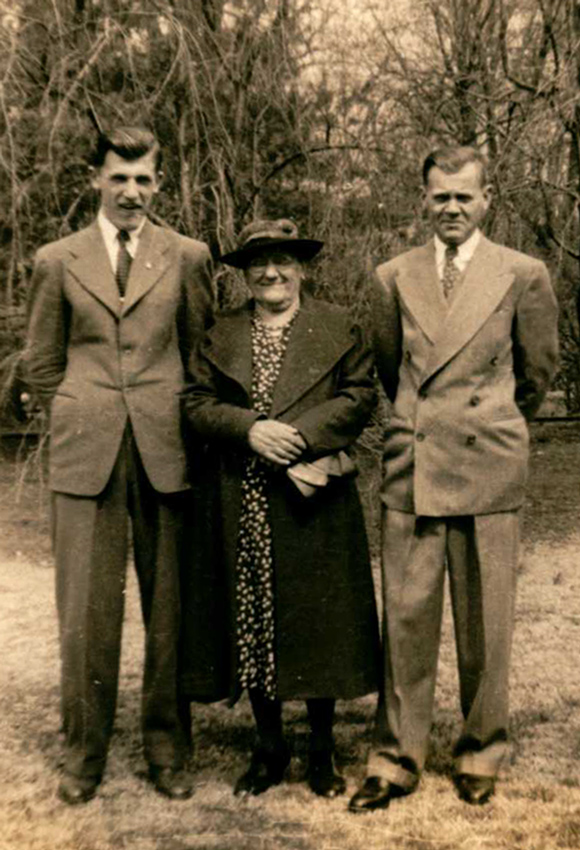

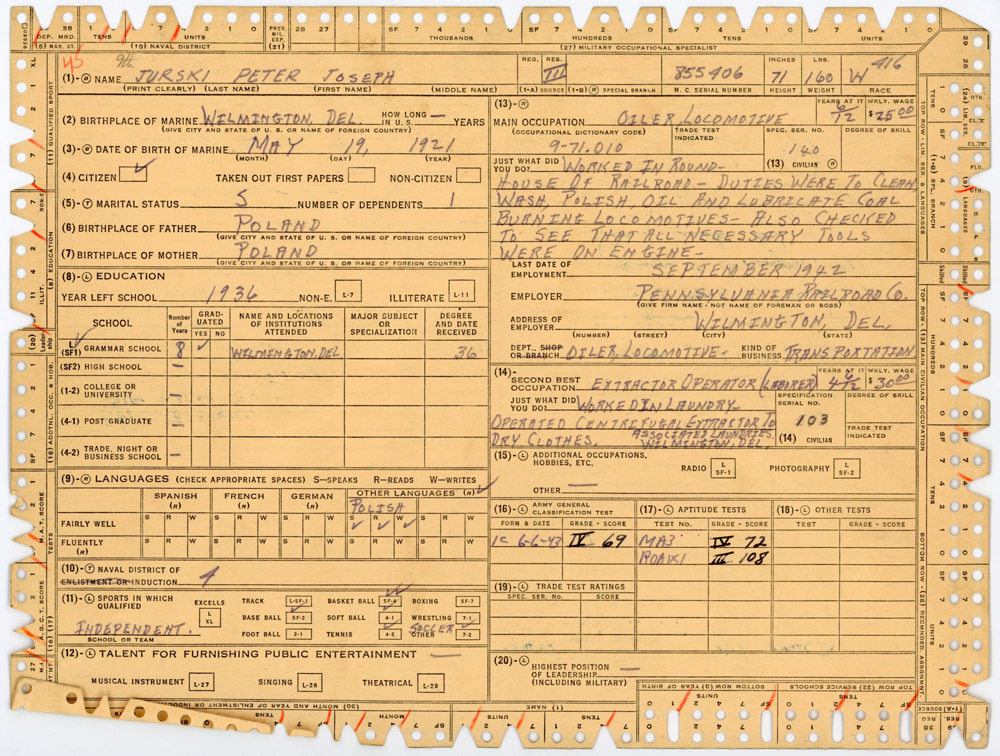

Peter Joseph Jurski was born Piotrz Jurski on May 19, 1921, at 8 Stroud Street in Wilmington, Delaware. Nicknamed Pete, he was the youngest son of Franciszek Jurski (also known as Frank Jurski, a laborer, d. 1939) and Akeksandra Jurksi (also known as Alexandra Jurski, a housekeeper, c. 1881–1959), Polish immigrants. He grew up with two older brothers, Walter Jurski (1904–1968) and Henry S. Jurski (1908–1989), as well as two older sisters, Genevieve Jurski (later Williams, 1916–2000) and Catherine Ann Jurski (later Laskowski, 1919–2005). Two other older siblings died young before his parents immigrated to the United States. He was Catholic.

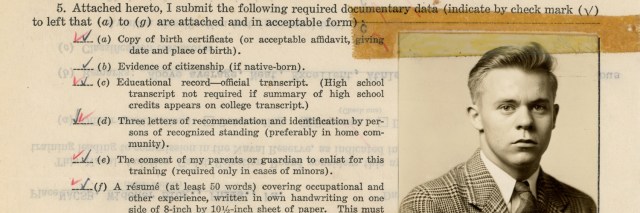

Jurski later told the Marine Corps that he could speak, read, and write Polish fairly well but not fluently, and that he played baseball, basketball, softball, tennis, and soccer.

On May 20, 1926, Jurksi’s parents purchased a home at 719 Warner Street in Wilmington. It appears that Jurski lived there until he entered the service. At the time of the census taken in April 1930, Jurski’s parents were unemployed, while his older brothers were working at a foundry and a cigar store respectively.

Jurski’s niece, Josephine Quinn, recalls being told that Jurski’s father was in poor health so the children stepped up to support the family. Jurski dropped out of school after completing the 8th grade in 1936. Prior to entering the military, he worked for 4½ years in the laundry business as an extractor operator, earning $30 per week. On May 6, 1939, shortly before Jurski turned 18, his father died of a heart attack.

When he registered for the draft on February 16, 1942, Jurski was working for Associated Wilmington Laundries at 2nd and Washington Streets. The registrar described him as standing about six feet tall and weighing 163 lbs., with brown hair and blue eyes. On the other hand, Jurski’s military paperwork described him as standing five feet, 9¾ inches tall and weighing 156 lbs., with brown hair and eyes.

From around March 1942 through September 1942, Jurski worked as a locomotive oiler for the Pennsylvania Railroad, earning $25 per week, cleaning and lubricating steam locomotives at a roundhouse.

Jurski’s mother told the Marine Corps that prior to entering the service, her son “was turning over to me 80% of his earnings which amounted to $ 20.00 per week.”

Military Career

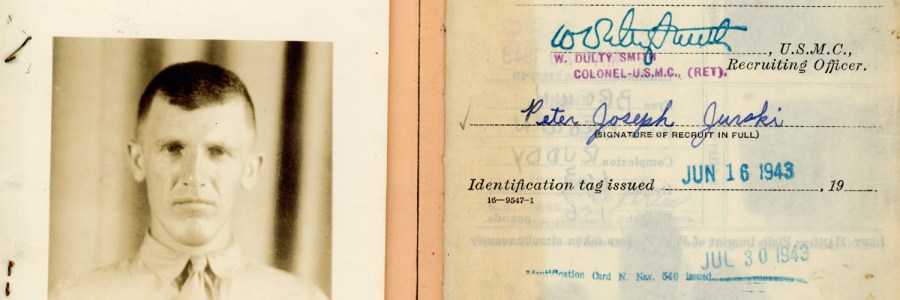

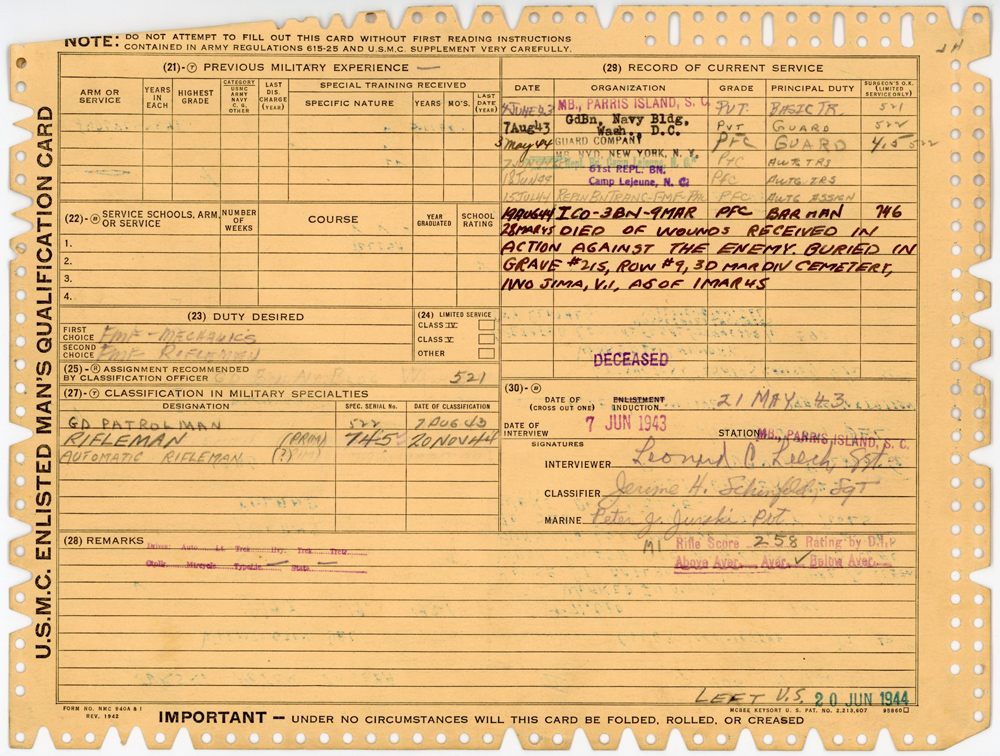

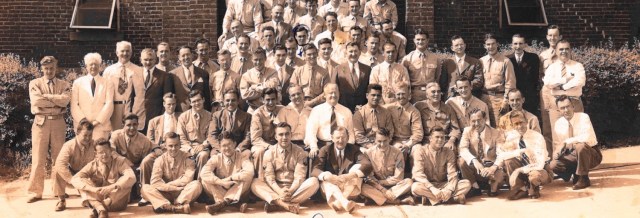

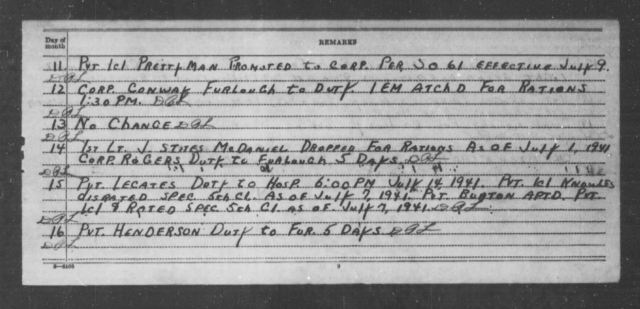

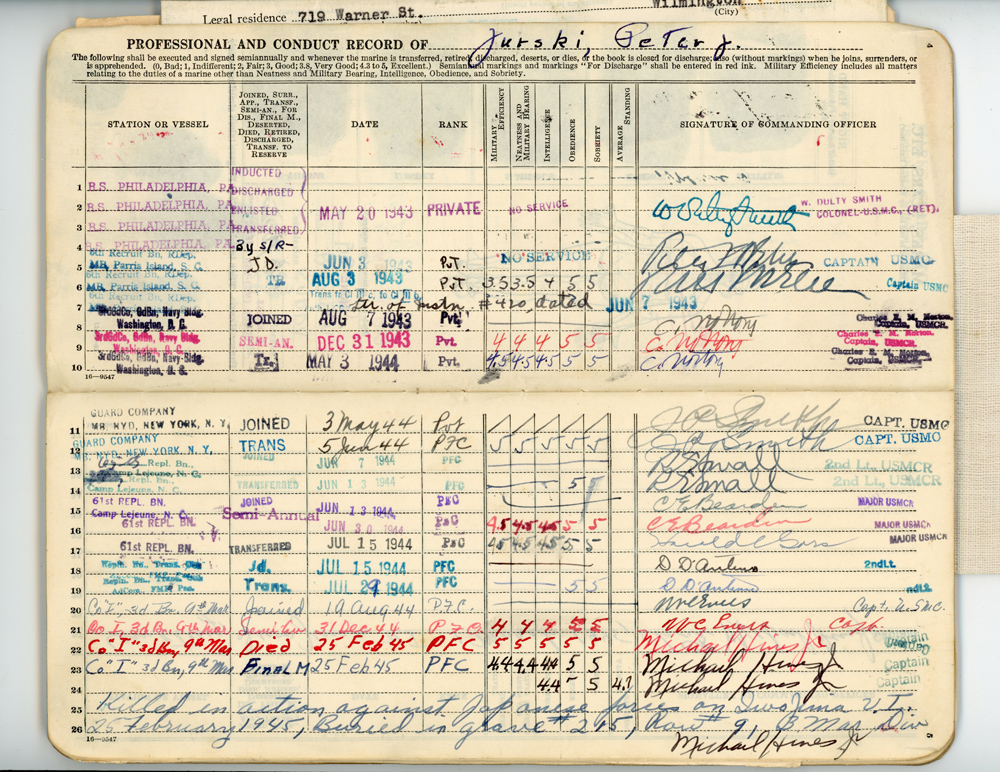

After he was drafted by Wilmington Board No. 3, Jurski joined the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 20, 1943, the day after he turned 22. He went on active duty on June 2, 1943, and traveled south by train. The following day, Private Jurski reported for boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, with the 6th Recruit Battalion.

After boot camp, on August 7, 1943, he joined the 3rd Guard Company, Guard Battalion, Navy Building, Washington, D.C. That day, his military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) was classified as 522, guard/patrolman. On May 3, 1944, Private Jurski transferred to the Guard Company, Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, New York, New York. The following month, on June 7, 1944, he transferred to 65th Replacement Battalion at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. On June 13, 1944, he transferred to the 61st Replacement Battalion at the same base.

Jurski was promoted to private 1st class on June 1, 1944. On June 19, 1944, at the Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, Virginia, Jurski and the rest of the 61st Replacement Battalion boarded U.S.S. Baxter (APA-94). The following day, with about 1,600 Marine and Navy passengers aboard, the attack transport got underway and sailed south. On June 26, 1944, Baxter arrived at Cristóbal, Canal Zone, transiting the Panama Canal the following day. After a brief stop at Balboa, she continued into the Pacific Ocean, arriving at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of July 11, 1944. Private 1st Class Jurski went ashore that afternoon.

On July 15, 1944, Jurski joined the Replacement Battalion, Transient Center, Administrative Command, Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific. According to a muster roll, on July 29, 1944, Private 1st Class Jurski sailed from Pearl Harbor, possibly aboard U.S.S. De Grasse (AP-164). On August 16, 1944, he arrived at Guam, Mariana Islands, where he joined 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines, 3rd Marine Division. There are discrepancies among documents in his personnel file but it appears that he joined Company “I,” 9th Marines on August 16 or 19, 1944.

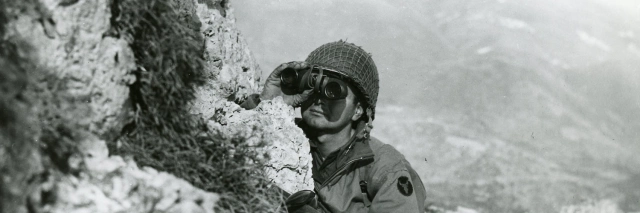

Although organized Japanese resistance on Guam had already ended, Jurski participated in patrols that sought out Japanese holdouts until November 1, 1944. Interestingly, his brother, U.S. Army Private 1st Class Henry S. Jurski, served briefly on Guam with Company “E,” 307th Infantry Regiment, 77th Infantry Division. However, their paths did not cross before Henry Jurski returned home for medical reasons.

Jurski sometimes closed his letters home “Hi Ho Silver,” a reference to his dog, Silver, as well as the famous Lone Ranger catchphrase. On September 18, 1944, he wrote to his sister, Catherine, that he was going on patrol again tomorrow. He asked her to send airmail stamps, stationary, a few copies of a Wilmington newspaper, and “a couple of bucks too.”

Patrols only took part of Private 1st Class Jurski’s time. More importantly, his unit prepared for their next major operation. Though none of them were yet privy to the details, the Marines expected a resolute, dug-in enemy. According to a regimental report about the Battle of Iwo Jima:

Prior to the action this regiment was stationed at GUAM and was undergoing intense training in infantry tactics. Among the most emphasized training subjects were: assault and reduction of pillboxes by small units, small unit tactics, infantry-artillery coordinated training. This training included a large amount of field firing of all types of Inf Wpns and demolitions.

According to his enlisted man’s qualification card, Private 1st Class Jurski’s principal duty with Company “I” was 746, automatic rifleman. That suggested that he manned a Browning Automatic Rifle (B.A.R.) in a four-man fire team or that he was an assistant automatic rifleman. Each fire team had a team leader, a B.A.R. man, an assistant B.A.R. man, and a rifleman. Aside from the B.A.R. man, the other three were armed with the M1 Garand rifle.

Confusingly, Jurski’s qualification card stated that as of November 20, 1944, his military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) was 745, rifleman, with automatic rifleman listed below it with a question mark. That may suggest that it was unclear to the person filling out the form whether Jurski was ever formally classified with the 746 M.O.S. or that it was unclear if 746 was indeed his principal duty. Indeed, Jurski was listed as a 745 on his unit muster rolls.

Historian Geoff Roecker cautions that it is “Hard to use the MOS as gospel for what a Marine’s role really was.” In his experience, M.O.S. codes in a Marine’s personnel file did not always match the testimony of veterans who served with him. Still, assuming his duty was 745 or 746, Jurski most likely served as part of the “tip of the spear” of a Marine rifle company.

On January 24, 1945, Private 1st Class Jurski wrote to his sister, Genevieve Williams:

I received your V Mail and I was glad to hear from you. I’m okay and still very Healthy. […] I’m glad to hear that you have snow in Delaware. I only hope that I will be home to see it again. […] I wonder if Silver misses me. To-day is Wednesday, I have a pretty rough day to-day. I feel tired. But I’m never too tired to write. Don’t worry about Henry, he will be all right.

The Battle of Iwo Jima

The capture of the Marianas had brought the Japanese Home Islands into range of American B-29 Superfortresses. Iwo Jima, which lay midway between the Marianas and Japan, had several airfields. Capturing the island would prevent Japanese fighters based there from attacking B-29s, provide a base for American escort fighters, and serve as a diversion airfield for bombers traveling to or from Japan. Despite its strategic significance, American planners had greatly underestimated the extent to which the Japanese defenders had fortified the small island.

Jurski and his comrades boarded the attack transport U.S.S. Leedstown (APA-56) at Apra Harbor, Guam, on February 9, 1945. They set sail on February 17, 1945, joining a convoy bound for Iwo Jima. The 3rd Marine Division was initially earmarked as a floating reserve. On the night of February 19, 1945, just after the battle began, Leedstown arrived at a staging area southeast of the island. On February 22 and 23, 1945, Leedstown stood by in the Outer Transport Area during the day and withdrew further offshore at night.

The Japanese had a reputation for tenacity, arguably demonstrated at its highest level on Iwo Jima. Unlike most prior battles, they avoided large-scale counterattacks that would have left them open to overwhelming American firepower, instead staying put in their positions as the 9th Marines action report explained:

From their cave and pillbox positions they could fire in any direction. When rockets, artillery, mortars and tanks supported our attack, the enemy moved deeper into his cave system until the preparation or barrage had ceased, then returned to his protected firing positions. Long after the pocket had been overrun and caves sealed, the enemy would dig or blast his way out and fight again.

Regimental Combat Team 9 (the 9th Marines with attachments) was called into action on D+5, February 24, 1945, landing on Iwo Jima that afternoon. The following day, Jurski’s 3rd Battalion was initially in reserve as the 9th Marines entered combat at Motoyama Airfield No. 2. The southern part of the field was already in American hands but the Japanese were determined to hold onto the northern portion. The 9th Marines action report stated:

The regiment was committed to action on 25 February by passing through the lines of the 21st Marines, 3d Mar Div. The initial attack commenced at 0930 following a heavy Arty [artillery] and Naval gunfire preparation with the 1st and 2d battalions abreast, 1st Bn on the right. Heavy fire from along the entire front met any of our advances. This resistance, the type of which was to prevail throughout the several weeks’ action, consisted of small arms fire from exceptionally well concealed positions, so well concealed in fact, that our troops were unable to locate the source in many instances until within 25 yards of it. Areas in defilade to one enemy automatic weapon were covered by another and presented a difficult problem throughout the action. In addition enemy mortar, artillery and occassionally [sic] rocket fire was well sighted in on all approaches to his positions and many times intense fire on our advancing troops and front lines caused severe damage and stopped any movement at its inception.

After 1st and 2nd Battalions slowly pushed forward for hours, Jurski’s 3rd Battalion entered the fight:

At 1430 o[n] the first day, the 3d Bn was committed to flank from the right the strong enemy positions holding up the 2d Bn. This battalion crossed the airfield between the first and second battalions at 199-V and in a rapid thrust succeeded in advancing 400 yards from the airfield. The advance was stopped abruptly as the enemy poured well aimed, intense Arty and mortar fire on the forward elements of this battalion thus interdicting them from the ground gained. The fire was so intense as to cause an adjustment of position by the 3d Bn to the north edge of the airfield where it tied in between the 1st and 2d Bns. The first day’s fighting then netted this regiment an advance all along its front of from 200 to 400 yards.

In a postwar monograph, Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic, Lieutenant Colonel Whitman S. Bartley (1919–2010) summarized the 3rd Battalion attack in greater detail:

The passage of lines was made at 1510, Company I on the left, K on the right, and Company L prepared to follow the left company to effect contact with the 26th Marines on order. A storm of small-arms and machine-gun fire from the front and flank pinned down the left unit almost immediately, but the rest of the battalion line advanced slowly by fire and movement. Both companies tortuously worked machine guns to forward positions to deliver covering fire, and Company K employed 60mm mortars against close-in targets. With Japanese mortar and artillery fire inflicting heavy losses among the slow moving Marines, the companies were directed to gain protection of the high ground to the front as quickly as possible. The left platoon withdrew from its sector where pillboxes held it up, and maneuvered to the right past the strong point.

As the troops crept ahead, the enemy adjusted his artillery to keep pace. The two assault company commanders were killed within a few minutes of one another, and other key personnel, officer and enlisted, fell in rapid succession. Both units faltered and began to draw back from the continuous blast of withering fire, losing contact with adjacent units in the process. Lieutenant Colonel Harold C. Boehm, commanding 3/9 [3rd Battalion, 9th Marines], acted quickly to regain control and reestablish contact with friendly elements. He sent his operations officer to take over Company K, which had suffered five officer casualties and was now seriously disorganized. Then he ordered this company to tie in with 1st Battalion on the right and committed his reserve, Company L, to effect a union with 2/9 on the left. Company I then became the center unit between L and K. By 1915 the situation was stabilized with contact established between all units along the regimental front.

The 3rd Battalion muster roll and action report indicates that most Company “I” casualties for February 1945 took place that first day of battle. It is possible that Private 1st Class Jurski was one of them, since it was the date of death recorded in his service record book, though a Marine Corps investigation determined that he was not hit that day. The regimental action report stated that on Iwo Jima, “By far the majority of our casualties were from enemy artillery fire. His intention apparently was to deny all prominent ground and approaches thereto by artillery fire once his troops had been driven off.”

Most of 3rd Battalion, including Company “I,” was the regimental reserve beginning on the morning of February 26. During the next two more days of grinding, close-quarters combat, the Marines hammered Japanese positions with artillery, naval gunfire, tanks, bazookas, and flamethrowers, finally capturing the rest of Airfield No. 2 on February 27, 1945.

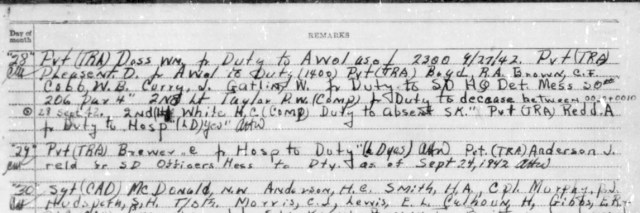

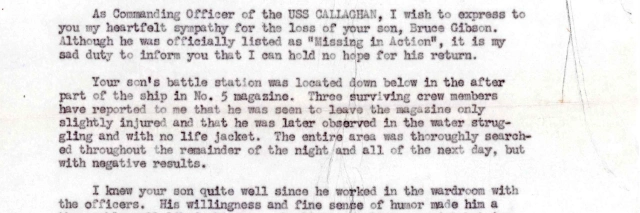

The following morning, February 28, 1945, around 0815 hours, the 21st Marines relieved the 9th Marines, which went into division reserve. Although the 3rd Battalion muster roll recorded few casualties that day, it stated Private 1st Class Jurski was mortally wounded by multiple shell fragments to his back and died the same day. A document suggests he was dead on arrival at the regimental aid station on February 28. Two other casualty lists also stated that he died of wounds on that day. Jurski was initially buried in the 3rd Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima the following day, March 1, 1945.

Recordkeeping in a combat zone is fraught with difficulty and there are discrepancies in dates of death for many World War II fallen, including Private 1st Class Jurski. Different documents list February 25, 1945; February 28, 1945; and March 1, 1945. There was also disagreement in various documents about whether he was killed outright or died of wounds. The Marine Corps investigated the discrepancies. The last was easily explained as erroneous, having conflated his date of burial with his date of death.

In the end, the Marine Corps determined that Private 1st Class Jurski died of wounds on February 28, 1945. The investigation did not explain why Jurski’s service record book, which is preserved in his personnel file, listed his death of February 25, 1945. Indeed, that was the date that the majority of Company “I” casualties occurred that month, when 3rd Battalion made its first assault. The company was in reserve for the rest of the month, though artillery shells could and did strike units in reserve. It is also possible that he died as early as February 25, but that in the chaos of battle he was not officially reported as missing prior to his body being located on February 28.

During World War II, it often took weeks for families to be notified when American servicemembers became casualties. Jurski was no exception. His sister, Catherine, wrote him with dread in mid-March 1945:

It isn’t like you not to write[.] The last letter we got from you was written Feb. 14[,] that’s over a month. I hope you are okay & hoping to hear from you real soon. Henry is happy being home. Only he’s restless, can [sic] seem to stay in one place.

The Wilmington newspapers reported Jurski’s death on March 31, 1945. By April 4, 1945, shortly before the 9th Marines left Iwo Jima, the regiment’s casualties from the battle stood at 565 men killed in action or died of wounds, 1,464 men wounded in action, and seven men missing.

Soon after learning about Jurski’s death, his older brother, Private 1st Class Henry S. Jurski, wrote a bitter letter that was preserved in Peter Jurski’s personnel file, and perhaps accompanied a form his family was submitting:

April 4, 1945

Dear Sir: –

I am enclosing this, whatever it is that was so hard to get fixed, it’s a shame we could not bring my brother from Iwo Jima to show that he is dead, nowaday [sic] you have to prove for everything, what are we fighting for is still a mystery to us guys, I know my brother did not know, neither do other million guys, maybe everything is a rackett [sic], and now we can’t get another business transaction fixed because the telegram and the letters do not tell on what date he was killed, so that lets [sic] us holding a bag, and probably the insurance will be something else that will be hard to get; so please try to make things easier and hoping everybody don’t have all that trouble that we have had, after we were dragged in the Army and the marines, even if my brother did not have any training he tried to do his best, it does make us guys hate everything that does not have a marine, a soldiers, or navy suit on, after sweating out with the Jap[anese].

Yours Truly

Pfc. Henry S. Jurski

Jurski was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. For the collective efforts of its men, the assault troops of V Amphibious Corps were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

In 1947, Private 1st Class Jurski’s mother requested that his body be repatriated to the United States for burial at Long Island National Cemetery in New York. His casket was shipped home the following year and reinterred there on April 8, 1948. His name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Like many immigrants from eastern Europe at that time, the dates of birth for Jurski’s parents are unclear. Various documents place Franciszek Jurski’s year of birth between 1868 and 1877. There are even fewer records available for Aleksandra Jurksi.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Private 1st Class Jurski’s nieces, Josephine Quinn and Ann Holdren, and to Geoff Roecker for providing photos, documents, and information, and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of its photos.

Bibliography

“9th Marines Action Report.” April 20, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/296176643/rep-of-ops-in-the-invasion-capture-of-iwo-jima-bonin-is-2191945-441945-page-145-us-world-war-ii-war-

“Action Report – 3d Battalion 9th Marines.” April 20, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/296176765/rep-of-ops-in-the-invasion-capture-of-iwo-jima-bonin-is-2191945-441945-page-206-us-world-war-ii-war-

Bartley, Whitman S. Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1954. https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/Iwo_Jima-_Amphibious_Epic.pdf

Carlisle, H. A. “Report of Action ‘Invasion of IWO JIMA, VOLCANO ISLANDS’, 8 February to 9 March 1945.” March 12, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/101713401

Census Record for Peter Jurski. April 3, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR4C-XLW

Certificate of Birth for Piotrz Jurski. Undated, c. May 19, 1921. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6LNZ-VRD

Certificate of Death for Franciszek (Frank) Jurski. May 6, 1939. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMJ-Y7YL-2

Deed Between Boleslaw Bialkowski and Mihalina Bialkowski, Parties of the First Part, and Franciszek Jurski and Alexandra Jurski, Parties of the Second Part. May 20, 1926. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_257009-00087

Draft Registration Card for Peter Joseph Jurski. February 16, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-X42F

Interment Control Form for Peter Joseph Jurski. May 6, 1948. Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/136928027?objectPage=1613

Jurski, Alexandra. Individual Military Service Record for Peter Joseph Jurski. February 28, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/19487/rec/2

Jurski, Catherine. Letter to Peter J. Jurski. March 1945. Courtesy of Ann Holdren.

Jurski, Peter J. Letter to Catherine Jurski. September 18, 1944. Courtesy of Ann Holdren.

Jurski, Peter J. Letter to Genevieve Williams. January 24, 1945. Courtesy of Ann Holdren.

“Marine Killed As Brother Comes Home.” Journal-Every Evening, March 31, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/165455019/

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps Third Battalion, Ninth Marines, Third Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force, in the Field, From 1 August to 31 August, 1944, inclusive.” August 31, 1944. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/194551180?objectPage=199

“Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps Third Battalion, Ninth Marines, Third Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force, in the Field, From 1 February to 28 February, 1945, inclusive.” February 28, 1945. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/194961352?objectPage=383

Official Military Personnel File for Peter J. Jurski. Official Military Personnel Files, 1905–1998. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Quinn, Josephine. Email correspondence on February 18, 2025.

Sinclair, V. R. War Diary for U.S.S. Baxter (APA-94) for July 1944. August 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78556768

Sinclair, V. R. War Diary for U.S.S. Baxter (APA-94) for June 1944. July 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78519936

Last updated on February 28, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.