| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Pennsylvania, Delaware | Worker at Pennsylvania Railroad shops |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32488346 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Company “D,” 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 636 (intelligence observer) and/or 745 (rifleman) | Battle of Salerno |

Early Life & Family

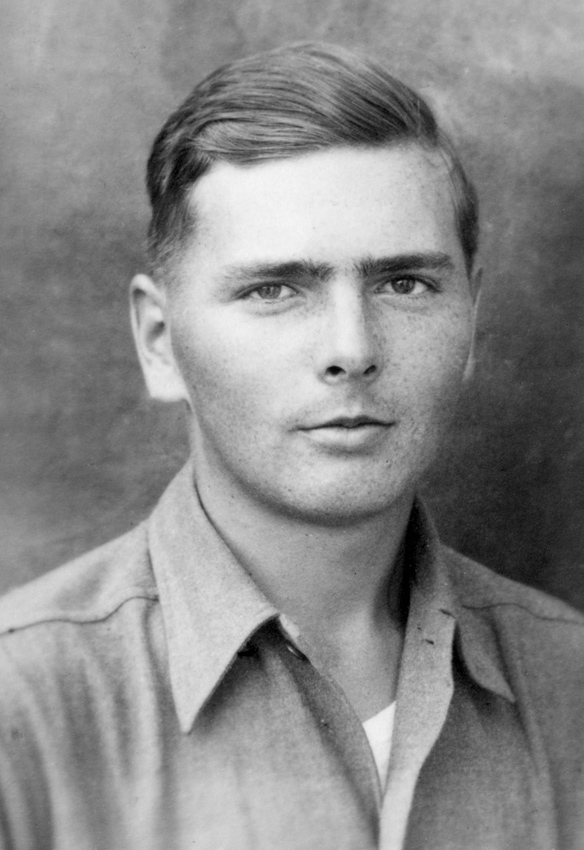

Ralph Armstrong Maloney, Jr. was born in Chester, Pennsylvania, on June 8, 1924. He was the son of Ralph Armstrong Maloney, Sr. (1899–1979) and Zelma Ellen Maloney (née Matthews, 1903–1994). He had a younger sister, Jane Elizabeth Maloney (later Baldwin, 1927–2004). He was Protestant.

The Maloney family was recorded on the census in April 1930 living at 120 Grant Avenue in Woodlyn, Ridley Township, Pennsylvania. Census records indicate that the family had moved to New Castle County, Delaware, by April 1, 1935. The family was recorded on the 1940 census living at 401 North DuPont Road in Richardson Park, outside of Wilmington, Delaware. Maloney’s father was described as a pipe fitter helper for a chemical manufacturer who had been out of work for nine weeks leading up to March 30, 1940. His mother was working as a first aid attendant at a fibre factory.

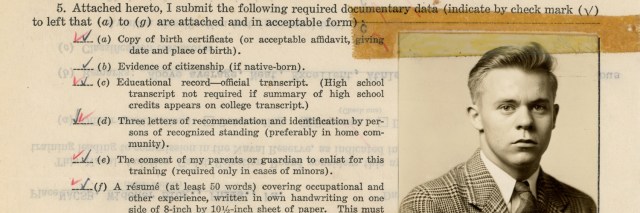

When Maloney registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, he was still living with his parents at 401 North DuPont Road and working at the Pennsylvania Railroad shops in Wilmington. (He is not named on the Pennsylvania Railroad World War II memorial in Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, so it is unclear if he was still working for the company when he entered the service.) The registrar described him as standing five feet, eight inches tall and weighing 140 lbs., with brown hair and hazel eyes.

Maloney’s enlistment data card stated that he had completed three years of high school, though it appears that he met the requirements to graduate. Journal-Every Evening reported: “Although he was not able to graduate with his class, he received his diploma from Henry C. Conrad High School. He was active in sports but was especially interested in guns and sharpshooting.” Similarly, his sister was quoted in their mother’s 1994 obituary: “My mother had to go and get his diploma from Conrad High School because he was drafted so quickly[.]”

Military Career

After he was drafted, Maloney was inducted into the U.S. Army on January 21, 1943. According to his mother’s statement, Private Maloney went on active duty on January 28, 1943. He was briefly attached unassigned at the 1229th Reception Center, Fort Dix, New Jersey. Beginning around February 2, 1943, he attended basic training at the Infantry Replacement Training Center, Camp Croft, South Carolina.

On May 10, 1943, Private Maloney reported for duty at the Shenango Personnel Replacement Depot in Transfer, Pennsylvania. The following day, he was attached unassigned to Company “B,” 5th Training Battalion, 2nd Training Regiment. His recorded military occupational specialty code was an unusual one for a man fresh out of basic training: 636, intelligence observer. However, a subsequent document indicated that he served as a rifleman in combat.

On or about June 2, 1943, Private Maloney was transferred to Shipment No. RU-550-AAA, and he went overseas on June 9. According to his mother’s statement, he shipped out from the New York Port of Embarkation. On June 22, 1943, Private Maloney was one of 600 enlisted men who were attached to and joined Company “C,” 8th Replacement Battalion, 1st Replacement Depot, at Canastel, Algeria. On July 14, 1943, Private Maloney and 82 other men were transferred to the 7th Replacement Depot. From there, he was transferred to the 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion on Sicily.

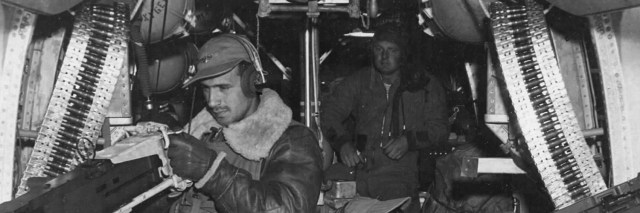

On August 5, 1943, Private Maloney and 20 other men joined Company “D,” 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion, which was bivouacked east of Caltanissetta, Sicily. It was a little over three weeks since the start of the Sicily campaign, though Maloney’s company did not see further combat before the defeat or evacuation of remaining Axis forces on the island. Since there is no indication in available records that Maloney attended any Ranger training stateside, he presumably had some training on Sicily to introduce him to the unit’s way of combat.

On August 9, 1943, Maloney and his new unit moved to Enna by road, where they were assigned to guard duty at a prisoner of war camp. On the afternoon of August 27, 1943, they moved west by road to Corleone.

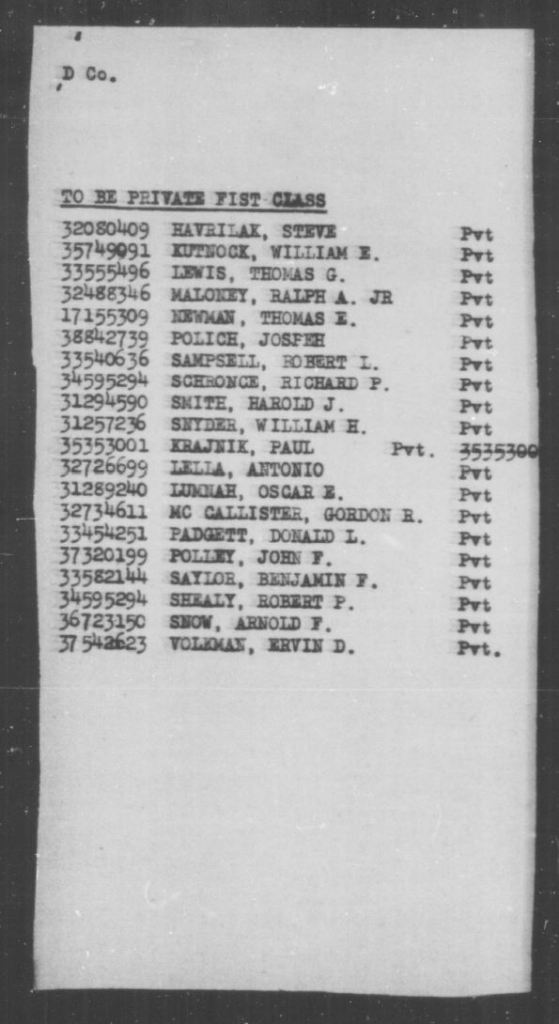

Maloney was promoted to private 1st class on September 1, 1943. Following additional training, on September 7, 1943, Maloney and his comrades moved by road to Palermo, where they embarked aboard the ex-Belgian ferry turned British landing ship H.M.S. Prince Leopold. They sailed from Sicily early the following morning.

Battle of Salerno

A series of Italian military disasters culminating in the fall of Sicily had led King Victor Emmanuel III (1869–1947) to sack Prime Minister Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) on July 25, 1943. The new regime under Pietro Badoglio (1871–1956) faced a conundrum. Although they wanted to end the war, they correctly anticipated that if they surrendered to the Allies, the German forces that had been helping to defend Italy would instead become its occupiers.

On September 3, 1943, the same day Commonwealth troops began landing on the tip of the “boot” of mainland Italy, the Italians secretly signed an armistice with the Allies. The news was not made public for another five days. Even then not all Italian forces had received the news by the time Allied forces began landing to the north near Salerno the following day.

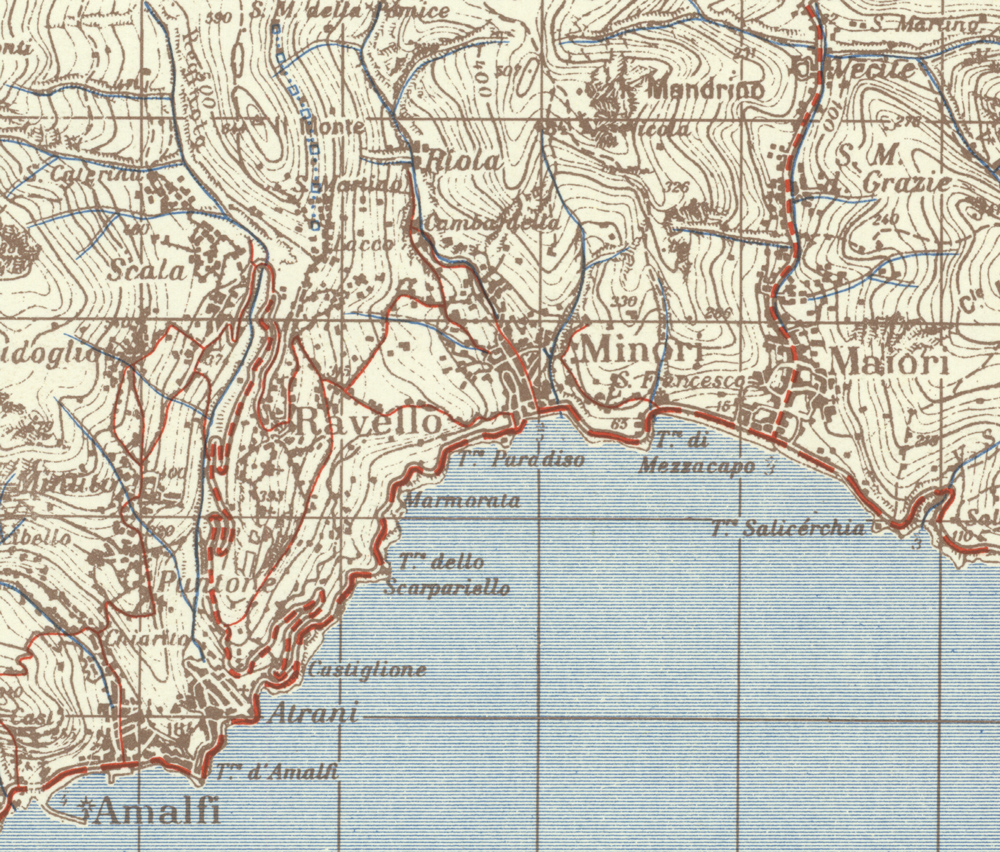

The 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Infantry Battalions plus attachments had orders to land at Maiori, on the Amalfi Coast west of Salerno, and secure the Chiunzi Pass to block German reinforcements. Maloney’s 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion was selected to lead the Ranger Force onto the beach.

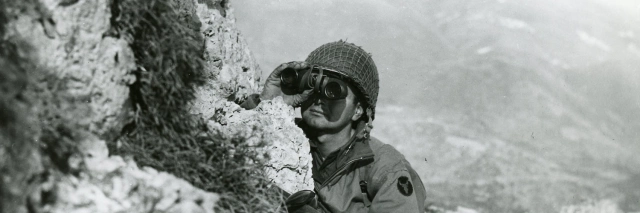

At 0130 hours on September 9, 1943, Private 1st Class Maloney and the rest of Company “D” boarded landing craft. Shortly after 0300, they landed unopposed at Maiori. Four companies, including Maloney’s, “cleared Maiori, and established beach head by occupying high ground overlooking Maiori” while Companies “A” and “F” cleared the coastal road on either side of the beachhead. Other elements of the Ranger Force landed and advanced to the Chiunzi Pass.

With the Salerno beachhead still in jeopardy from German counterattacks, the Rangers remained in combat. On the afternoon of September 11, 1943, Maloney and his company moved west to Pimonte by truck and foot. The following evening, Companies “A” and “D,” 4th Rangers, along with Company “H,” 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, launched an unsuccessful attack on Gragnano.

On September 13, 1943, Maloney and the others moved by truck back to Maiori and then to Salerno, the main landing site for the U.S. Fifth Army. The following day, they moved to Polvica.

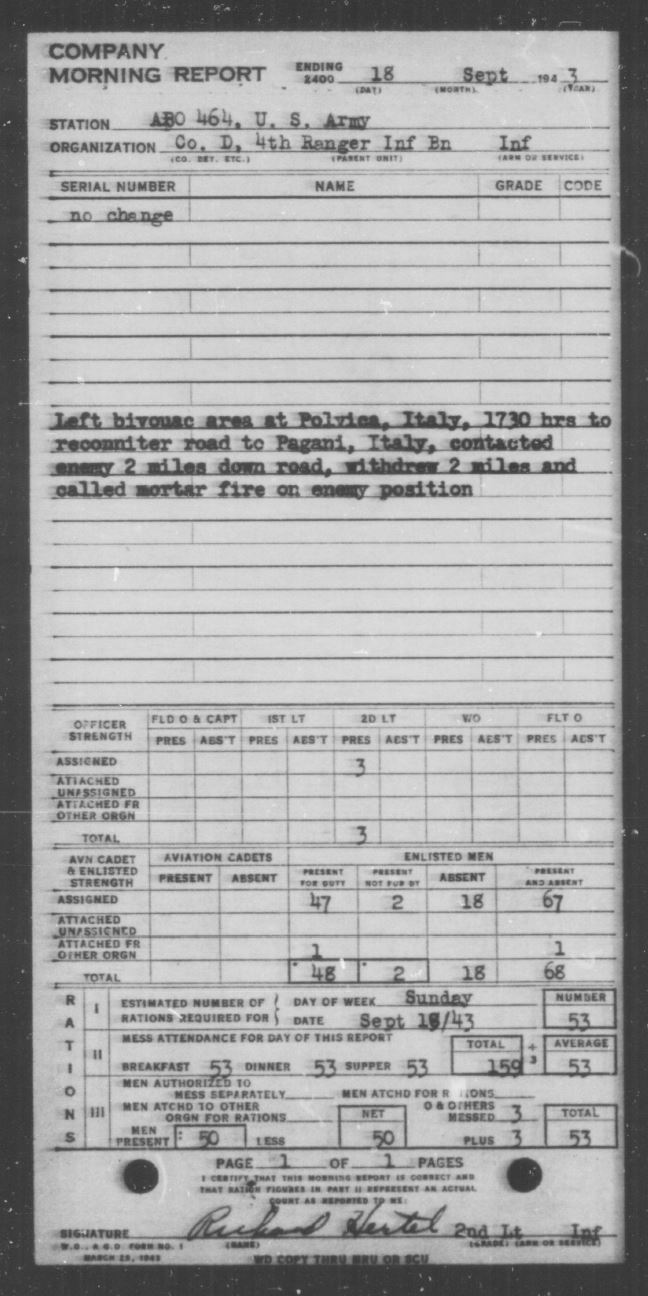

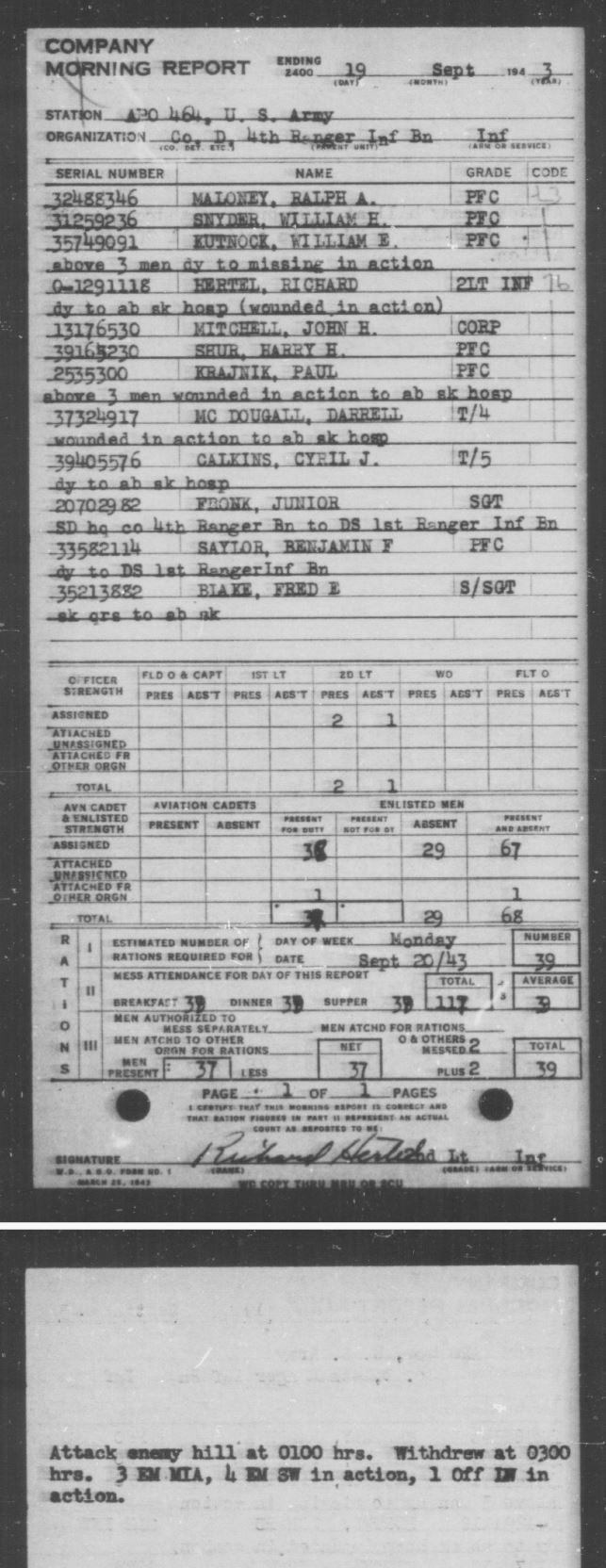

The battalion after action report stated that on September 18, 1943:

Company D, with one Engineer officer, and one Signal [Corps] officer and five enlisted men attached, proceeded at 2030 hours, from Chiunzi, down the road toward Sala, with mission to reconnoiter for road blocks, mines, or prepared demolitions. Heavy fire from automatic weapons and grenades was encountered from hill (508-358 [40° 43’ 22” North, 14° 36’ 06” East]). One platoon attacked the hill, the other platoon with attached personnel, moved down the road to Sala, removing various mines and cutting enemy communication lines. Resistance was heavy, resulting in the Company Commander and five enlisted men being wounded, with three enlisted men missing in action. Approximately sixteen Germans were killed or wounded.

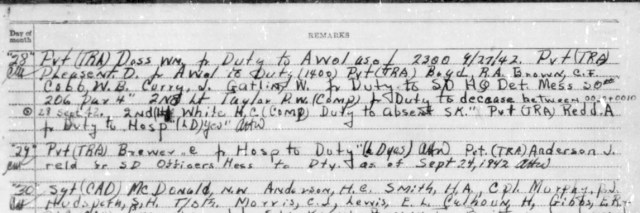

The Company “D” morning reports for September 18 and 19 provide a slightly different account, describing a pair of engagements with different times than the battalion after action report: “Left bivouac area at Polvica, Italy, 1730 hrs to reconn[o]iter road to Pagani, Italy, contacted enemy 2 miles down road, withdrew 2 miles and called mortar fire on enemy position[.]”

According to the next morning report, dated September 19, 1943, Company “D” attacked an enemy hilltop position that night, beginning at 0100 hours. After two hours of fighting, the Rangers retreated. This morning report recorded casualties of three men missing in action (M.I.A.), including Private 1st Class Maloney, and five men wounded.

Maloney’s body had been located by September 28, 1943, when a Company “D” morning report recorded that his status had changed from M.I.A. to killed in action (K.I.A.) No dog tags were found on Maloney’s body, but he was identified by the emergency medical tag that a medic had attached to his body. He was initially buried at Maiori on September 29, 1943. Despite that, the Adjutant General’s Office held him as M.I.A. until October 14, 1943.

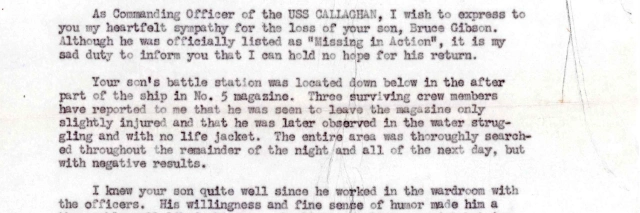

Although his burial report did not reveal cause of death beyond that Maloney was killed during combat, a letter to his family from Colonel E. C. Gault of the Adjutant General’s Department dated April 4, 1945, apparently based on Maloney’s personnel file, stated:

He was killed in action as a result of a gunshot wound on 18 September 1943, while serving as a private first class in Italy. His Army specialty was rifleman. His character and efficiency rating as a soldier were recorded as excellent.

The other two missing men, Private 1st Class William E. Kutnock (1923–1943) and Private 1st Class William H. Snyder (1919–1943), were also subsequently determined to have been killed. The War Department eventually issued a finding of death for Kutnock and Snyder. Neither of their bodies were ever recovered.

A third account of the events of September 18–19, 1943, a statement by 1st Lieutenant Richard P. Honig (1920–1979) written in July 1944, was quoted in Private 1st Class Kutnock’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.):

“We left Chiunzi Pass at 1030 [sic] with selected men in the lead. These men were to do most of the reconnoitering work, while the remainder of the company would be set up in a good position to cover the men doing the reconnoitering and help with the withdrawal if necessary. The road ran down a very steep mountain side, and in many places it was impossible to leave the road; therefore it was planned to stay on the road as long as possible.

“The remainder of the company was left in a position to cover the reconnoitering party. This group had not moved over 600 yards before they contacted the enemy. The company was then reformed and one platoon was given a job of wiping out the enemy strong point while the other platoon was sent on down to finish the reconnoitering.

“The platoon continued on down the road removing mines and cutting communication wire. It had gone nearly a mile and a half when it ran into another road block. There was a skirmish there which lasted about ten to fifteen minutes. By this time it was nearly 0300 hours 19 September.

“When the enemy was contacted the order was given to deploy on either side of the road and commen[c]e fire. To complete the deployment of the sections the section leaders had to withdraw about 100 yards, for on either side of the road was a shear drop.

“Private first class Snyder was one of the men in the point. The point and leading elements of the platoon were in among the enemy. Fire was exchanged at point-blank range and grenades were thrown by both sides. The last I saw of Snyder, he was jumping off the road and heading back toward our sections. When he was reported missing by his leader, questions were asked about where he was last seen. Someone said he was seen heading back to the rear. He had been wounded in the back apparently by a grenade fragment. The person who last saw him couldn’t tell whether he was hurt badly or not.

“Private first class Kutnock was at the rear of the platoon and when the section deployed he was apparently hit. When questions were asked concerning Kutnock, nobody remembers seeing him after the deployment was made.

“A search was made for these men that night. We were too close to the enemy to use word of mouth so therefore it was not effective. The next night another detail was sent out with a litter but with no results.

“After an attack was made and the enemy driven back a search was made for graves or bodies. The body of Private Maloney was found but not Kutnock.”

Although focused on the fates of Kutnock and Snyder, Lieutenant Honig’s statement provides a great deal more clarity than either the battalion after action report or the Company “D” morning reports. That the mission began at 1030 is likely an error introduced when the statement was retyped for the I.D.P.F. Regardless, the Honig statement makes it clear not only that there were two separate engagements that night, but that the engagements occurred at two different places: the German-occupied Hill 540 and at another roadblock to the west.

Honig’s statement implies that Maloney and the others were killed during a firefight with a roadblock west of Hill 540. The exact location of the roadblock is unclear beyond that it was in area so steep that flanking the position by going offroad was impossible. Much of the area has a drop off on one side of the road and steep mountainside on the other. If both sides had a drop off like Honig recalled, a likely location for the roadblock is on the map near the “t” in in “marante,” northwest of Hill 540 and north of Pigno. (McMaster University Library)

There is a discrepancy about Private 1st Class Maloney’s date of death, though he clearly was killed the night of September 18–19, 1943. A Company “D” morning report listed him as killed in action on September 19, 1943. On the other hand, the Adjutant General’s Office report of death stated that he had died on September 18, 1943.

Although not stated explicitly in Honig’s statement, it is strongly implied that Maloney, Kutnock, and Snyder were all members of the reconnaissance party and that all three men were killed or mortally wounded during the firefight with the roadblock around 0300 hours on September 19, 1943.

Despite the casualties, the reconnaissance mission was successful and the 1st and 3rd Ranger Infantry Battalions later took Sala.

Maloney, Kutnock, and Snyder had all trained at Camp Croft in early 1943 and been members of a group of 21 replacements who joined Company “D” on August 5, 1943. Of that cohort, six were killed and one wounded during the Battle of Salerno. Two more were killed and seven more wounded or injured through the spring of 1944, an astonishing 76% casualties.

Journal-Every Evening reported on October 6, 1943, that Maloney was missing in action. The paper confirmed his death on October 16.

Private 1st Class Maloney’s personal effects included a notebook, a Bible, 20 photographs, and a money belt. On July 25, 1944, Maloney was reburied at a temporary military cemetery at Monte Soprano, Italy.

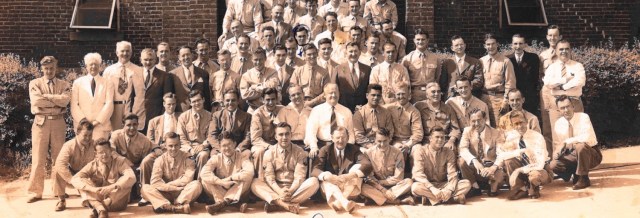

The 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for the collective actions of its members during the Battle of Salerno.

After the war, Maloney’s parents requested that his body be repatriated to the United States. Maloney’s body returned home from Naples, Italy, to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the Carroll Victory. A military escort accompanied the casket by train to Wilmington on August 3, 1948. After his funeral the following day at Richardson Park Methodist Church, he was buried at Gracelawn Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware. His parents and sister were also buried there after their deaths. Maloney’s name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park nearby.

Notes

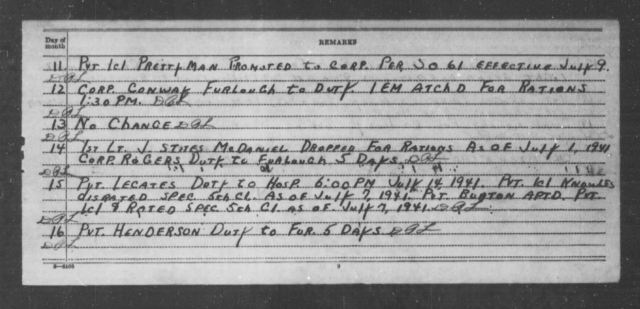

Basic Training

Private Maloney was attached for rations and quarters to Company “C,” 35th Infantry Training Battalion on February 2, 1943. However, according to his mother’s statement, Maloney attended basic training attached to Company “B,” 35th Infantry Training Battalion. That is plausible, but unconfirmed in available records. A Company “C” morning report stated that a group of men were detached on February 4, 1943. The same day, a group of men were attached unassigned to Company “B.” Unfortunately, the names of these individuals were not revealed.

Grade

A Company “D” morning report stated that 20 men were promoted to private 1st class on September 1, 1943, including Maloney, Kutnock, and Snyder. Curiously, all three men were listed as privates on the official U.S. Army casualty list published in 1946. Private 1st class was a promotion at the company level and would not have needed confirmation from higher headquarters. Maloney’s headstone does show his grade as private 1st class, as do Kutnock and Snyder’s entries on the Tablets of the Missing at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Nettuno, Italy.

Private 1st Class Snyder

A letter by Private 1st Class Snyder’s mother, Wilhelmina Emily Snyder (1893–1975), dated August 9, 1944, stated in part:

I am his only living relative and I am deeply grieved that he is missing. But I am not giving up hope, for I have two letters from his Section Sargeant telling me exactly what happened. He was seriously wounded and the Sargeant picked him up from the battle field and hid him in a barn, but when he, the Sargeant returned with a stretcher and bearers he, my Son was gone. There was evidence of first aid, bandages and an empty plasma bottle, but my Son could not be found. This I feel looks as though he was picked up by the enemy and soon, some day will be found.

As of Februrary 2025, Snyder’s body has still not been recovered.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Julie Foley Belanger, Ron Hudnell, and Julie Fulmer, the Darby Foundation, and the Delaware Public Archives for contributing photos, documents, and information.

Bibliography

Altieri, James J. Darby’s Rangers: An Illustrated Portrayal of The Original Rangers. The Ranger Book Committee, 1977. Courtesy of Julie Foley Belanger and the Darby Foundation.

“Army Notifies 2 City Families Of Death of Sons in Action.” Journal-Every Evening, October 16, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/165732212/

Black, Robert W. Rangers in World War II. Ballantine Books, 1992.

Census Record for Ralph A. Maloney. April 5, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RCQ-71N

Census Record for Ralph A. Maloney, Jr. May 7, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9MR-MD2

Draft Registration Card for Ralph Armstrong Maloney, Jr. June 30, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_04_00006-01427

Enlistment Record for Ralph A. Maloney, Jr. January 21, 1943. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32488346&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3099277

Hospital Admission Card for 32488346. U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/702412376/maloney-ralph-a-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Ralph A. Maloney, Jr. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for William E. Kutnock. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for William H. Snyder. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Maloney, Zelma E. Individual Military Service Record for Ralph Armstrong Maloney, Jr. Undated, c. 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/19765/rec/1

Morning Reports for Company “C,” 8th Replacement Battalion, 1st Replacement Depot. June 1943 – July 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2514/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2514-17.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “D,” 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion. August 1943 – September 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-08/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0468/85713825_1943-08_Roll-0468-22.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0562/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0562-16.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1943-09/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0562/85713825_1943-09_Roll-0562-17.pdf

Morning Reports for Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment, 35th Infantry Training Battalion, Infantry Replacement Training Center, Camp Croft, South Carolina. February 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1971/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1971-07.pdf

Morning Reports for Replacements, Company “B,” 5th Training Battalion, 2nd Training Regiment, Shenango Personnel Replacement Depot. May 1943 – June 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2881/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2881-10.pdf, https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2881/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2881-11.pdf

Murray, Roy A. Jr. “Report of Action (9 Sept to 29 Sept).” October 5, 1943. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Pvt. Ralph A. Maloney Is Reported Missing.” Journal-Every Evening, October 6, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/161721091/

“Pvt. Ralph Armstrong Maloney Jr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53700837/ralph-armstrong-maloney

“Ralph A. Maloney, Jr.” Wilmington Morning News, August 3, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/article/161721205/

“Zelma E. Maloney.” The News Journal, August 8, 1994. https://www.newspapers.com/article/161721418/

Last updated on February 26, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.