| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Indiana, Delaware | Railroad worker and/or driver |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | Enlisted 32070703 / Officer O-1102497 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Zone of Interior (American) | Company “D,” 34th Battalion, Engineer Replacement Training Center, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri |

Early Life & Family

Paul Winfred Taylor was born in Shelbyville, Indiana, on September 16, 1911. He was sixth child of Alfred Taylor (a machinist at the time, 1875–1958) and Martha A. Taylor (née Hines, 1873–1957). An older sibling died prior to his birth. He grew up with two older brothers, two older sisters, a younger sister, and a younger brother.

The family was still living in Shelbyville as of April 10, 1917, when Taylor’s youngest brother, George William Taylor (1917–1992, who also served in the U.S. Army during World War II), was born. Journal-Every Evening reported that Taylor “came here [to Wilmington] with his parents during World War I.” As of January 1, 1920, the family was living at 625 Windsor Street in Wilmington. Taylor’s father was working as a porter. By April 1, 1930, the Taylors had moved to 610 West 7th Street in Wilmington. It appears that Taylor lived there until he entered the service.

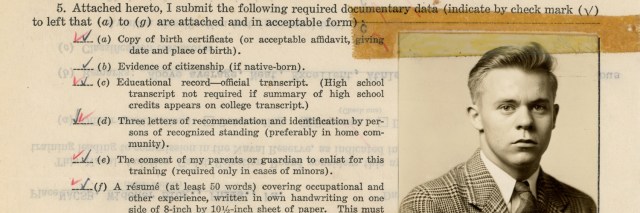

Journal-Every Evening reported that Taylor graduated from Howard High School in Delaware and Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland. The paper added that Taylor “was a member of the Masonic lodge here and of Bethel A. M. E. Church.”

When he registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, Taylor was working for the Pennsylvania Railroad. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, seven inches tall and weighing 155 lbs., with black hair and brown eyes.

Taylor married Hazel Beatrice Mason (1918–1996?) in Wilmington on September 25, 1941. His occupation was listed as railroad messenger on their marriage certificate.

Taylor’s mother told the State of Delaware Public Archives commission that her son was a railroad clerk and college student prior to entering the service. On the other hand, Taylor’s enlistment data card described his occupation as “semiskilled chauffeurs and drivers, bus, taxi, truck, and tractor.”

Military Career

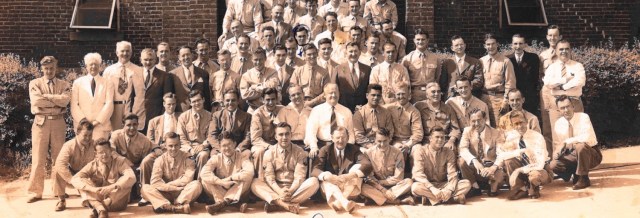

Taylor was drafted before the U.S. entered World War II. He was inducted into the U.S. Army in Trenton, New Jersey, on March 31, 1941. That same day, he reported for duty at Fort Dix, New Jersey. He was attached to Company “E,” 1st Receiving Battalion, 1229th Recruit Reception Center.

Taylor’s personnel file was among those lost in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire and surviving documentation is incomplete. It is unclear how far Taylor progressed in his training during 1941, but presumably he completed at least basic training and was promoted to private 1st class before he left active duty and was transferred to the Enlisted Reserve Corps.

On or about January 17, 1942, Private 1st Class Taylor was recalled to active duty and was attached back to Company “E,” 1229th Reception Center. His movements until early May 1942 are unclear.

The U.S. Army segregated black soldiers at the time. It was extremely difficult for them to become officers, with only limited slots allocated. The segregated and deeply unequal educational system greatly reduced the number of black officer candidates who could meet the educational and testing requirements to be selected for Officer Candidate School (O.C.S.).

Those black soldiers who managed to overcome these obstacles to earn commissions were forbidden to command white soldiers. The reverse was not true and most black units were commanded either in whole or in part by white officers. This policy effectively ensured that the few black officers available would largely remain junior officers since however capable one may be, he could not be promoted to command a battalion, for instance, without first transferring out every white officer in that battalion. Promotions for black officers often occurred only when a new unit was created with a cohort of officers transferred as a group. The Army’s segregation policies also created enormous inefficiencies since separate replacement officer pools had to be maintained. Some black officers lingered for extended periods waiting for vacancies.

In his book, The Employment of Negro Troops, Dr. Ulysses Lee (1913–1969) wrote that as of August 1942—coincidentally, the same month that Taylor was commissioned—just 817 (0.34%) of the Army’s 244,000 officers were black. Only 0.36% of black soldiers were officers, compared with 7% of soldiers overall.

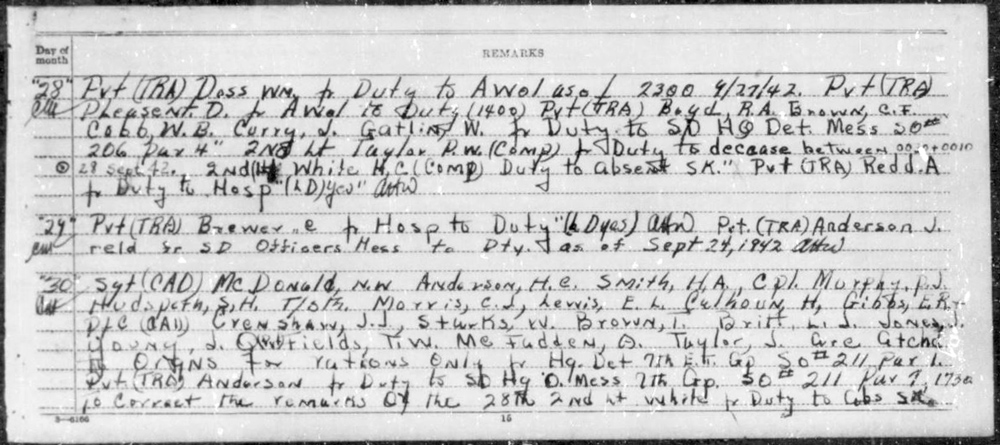

In early May, Taylor began O.C.S. The Wilmington Morning News reported that on August 5, 1942, Taylor and two other Delawareans “were graduated from the Army Engineer Officer Candidate School, Fort Belvoir, Va, Wednesday, and were commissioned second lieutenants.”

According to his mother’s statement, Taylor ranked 10th in his class of 193 at O.C.S.

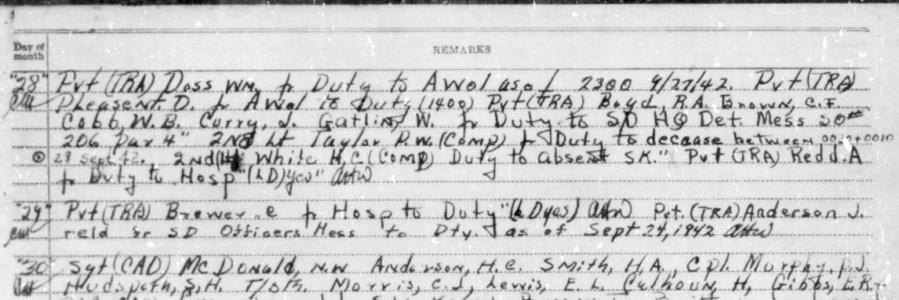

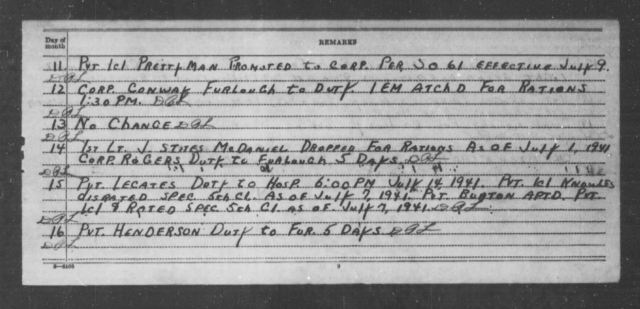

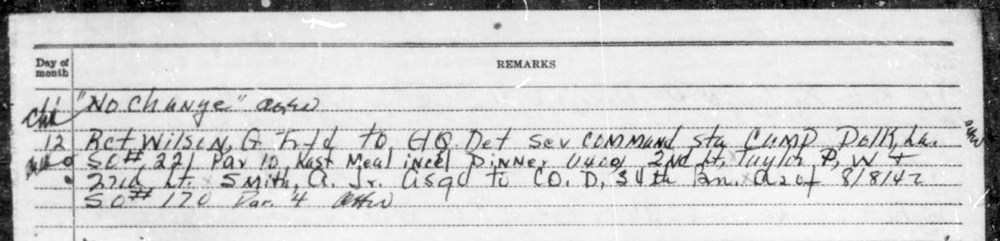

On August 8, 1942, 2nd Lieutenant Taylor was assigned to Company “D,” 34th Battalion, Engineer Replacement Training Center, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, as a company officer. Some bureaucratic shuffling followed. 2nd Lieutenant Taylor was released from the assignment but attached to Company “D” on August 20, 1942. This status change was reversed on September 3, 1942, when he was released from attachment and became a full member of Company “D” again.

Company “D” had a handful of lieutenants, presumably instructors, and about 245 privates as trainees. Curiously, it had no enlisted cadre of noncommissioned officers.

It appears that Lieutenant Taylor was able to celebrate his 31st birthday with his wife. Journal-Every Evening reported that Hazel Taylor spent two weeks visiting her husband in Missouri before leaving for Delaware on September 26, 1942.

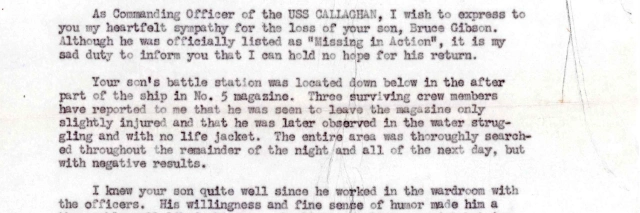

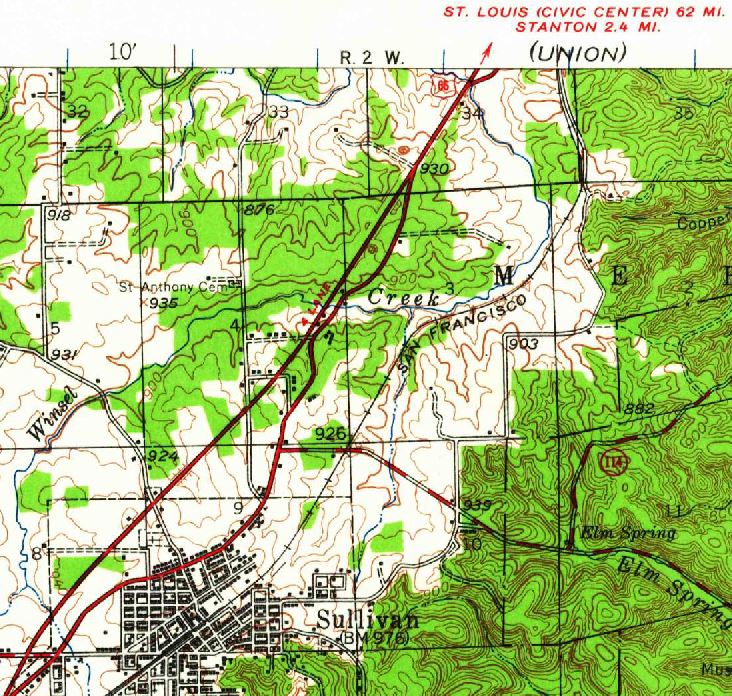

On the night of September 27–28, 1942, Taylor and five other officers were traveling back to Fort Leonard Wood on U.S. Route 66 in a Chevrolet coupe. Shortly after midnight their vehicle collided with a cattle truck roughly midway between the towns of Stanton and Sullivan, Missouri. Three men were killed: 2nd Lieutenants Taylor, Ennas Calvin Cave (1919–1942), and Booker T. Owens (probably 1913–1942), the driver.

The St. Clair Chronicle reported:

Glen Maples of Maples, Mo., driver of the International cattle truck and William Morgan, also of Maples, Mo., who was riding with Maples, told highway patrolmen, that they were coming east, driving at 35 miles an hour and as they were coming around a curve on the Highway, the Chevrolet coupe, occupied by the six Negro officers, was coming towards them on the wrong side of the highway at a very rapid rate of speed. Maples said he swung his truck to the opposite side of the road, to try to avoid the collision but the oncoming car hit him head-on, before he could get to the shoulder. The car was completely demolished and estimated damage to the truck is six hundred dollars.

According to their death certificates, Taylor and Cave died due to neck fractures and Owens from head trauma. Five men were injured: The occupants of the cattle truck and 2nd Lieutenants Seward Boyd (1908–2001), Clarence Todd (likely 1914–1977), and Henry C. White (likely 1915–1984, a member of Taylor’s company). The survivors were treated at St. Francis Hospital in Washington, Missouri, while Taylor and the other “dead were brought to an undertaking parlor in St. Clair and later in the day, an Army ambulance came for the bodies.”

In the years after the accident, U.S. 66 was upgraded in the area where the accident took place, with additional lanes added and the alignment straightened. Much of U.S. 66 near Stanton was eventually incorporated into Interstate 66.

Journal-Every Evening reported that Hazel Taylor was still in transit when her husband was killed and that it was only when she arrived back in Wilmington on the night of September 28, 1942, that she learned of the tragedy.

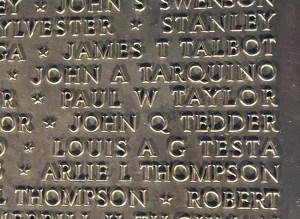

2nd Lieutenant Taylor’s funeral services took place in Wilmington. On October 3, 1942, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. His name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware, and on the Pennsylvania Railroad World War II Memorial at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Notes

Location of Collision

Various sources give slightly different locations for the crash on U.S. 66. The death certificates state the accident occurred two miles west of Stanton, while The St. Clair Chronicle stated it occurred 2½ miles east of nearby Sullivan. That suggests it was roughly midway between the two towns.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Austin Whittall for providing information about Route 66 and locating an article about the crash that I missed. Thanks also go out to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

“According to the…” The Sullivan News, October 1, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/157268133/

Application for Headstone for or Marker for Ennas Calvin Cave. January 27, 1943. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_644066_0367-03499

Census Record for Paul Taylor. April 14, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHM-JTN

Census Record for Paul Taylor. April 16, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-M9RS

Census Record for Paul Taylor. January 12, 1920. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9R6C-685

Certificate of Birth for George William Taylor. April 10 or 11, 1917. Birth Certificates, 1907–1944. Indiana Archives and Records Administration, Indianapolis, Indiana. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60871/images/45385_539577-01395

Certificate of Birth for Hazel Beatrice Mason. July 4, 1918. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DRJ7-3FX

Certificate of Birth for Paul Winfred Taylor. September 18, 1911. Birth Certificates, 1907–1944. Indiana Archives and Records Administration, Indianapolis, Indiana. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60871/images/40474_358020-00401

Certificate of Marriage for Paul W. Taylor and Hazel D. Mason. September 25, 1941. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-X3SS-Y7X

Draft Registration Card for Paul Winfred Taylor. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-63Q5-D

Enlistment Record for Paul W. Taylor. March 31, 1941. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32070703&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=2740023

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Paul W. Taylor. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Interment Control Form for Paul W. Taylor. Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_649063_0461-03513

Lee, Ulysses. The Employment of Negro Troops. Originally published in 1963, republished by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 2001. https://www.history.army.mil/html/books/011/11-4/CMH_Pub_11-4-1.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “D,” 34th Engineer Training Battalion. August 1942 – September 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1157/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-1157-36.pdf

Morning Reports for Company “E,” 1st Receiving Battalion, 1229th Recruit Reception Center. March 1941. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2846/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2846-08.pdf

Morning Reports for Enlisted Reserve Corps Men of Company “E,” 1st Battalion, 1229th Reception Center. January 1942. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2847/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-2847-15.pdf

“Negro Soldiers Kiiled [sic] In Automobile Collision.” The New Haven Leader, October 1, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/118191776/

“Officer’s Body On Way Here.” Journal-Every Evening, September 29, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/118077255/

“Samuel Cothern Cummings Jr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/12277127/samuel-cothern-cummings

Shine, Dan. “Seward Boyd: Executive was a cowboy at heart.” Detroit Free Press, November 19, 2001. https://www.newspapers.com/article/157305669/

Standard Certificate of Death for Booker T. Owens. September 28, 1942. Missouri Death Certificates, 1910–1969. Missouri Office of the Secretary of State, Jefferson City, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60382/images/1942_00033684-01122

Standard Certificate of Death for Ennas C. Cave. September 28, 1942. Missouri Death Certificates, 1910–1969. Missouri Office of the Secretary of State, Jefferson City, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60382/images/1942_00033671-01108

Standard Certificate of Death for Paul W. Taylor. September 28, 1942. Missouri Death Certificates, 1910–1969. Missouri Office of the Secretary of State, Jefferson City, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60382/images/1942_00033689-01652

Taylor, Martha A. Hines. Individual Military Service Record for Paul W. Taylor. Undated, c. 1949. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/21069/rec/2

“Three Fort Wood Negro Officers Killed in Crash.” The St. Clair Chronicle, October 1, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/157268452/

“Three Killed In Auto Wreck.” The Washington Missourian, October 1, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/157267518/

“Three Killed In Collision With Cattle Truck.” Washington Citizen, October 2, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/157267892/

Whittall, Austin. “All about Route 66 in Stanton, Missouri.” TheRoute-66.com website. https://www.theroute-66.com/stanton.html#map

“With the Service Men.” Wilmington Morning News, August 7, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/156432442/

Last updated on October 18, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.