| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware, Pennsylvania?, North Carolina, Maryland | Machinist |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army Air Forces | 13135889 |

| Theater | Unit |

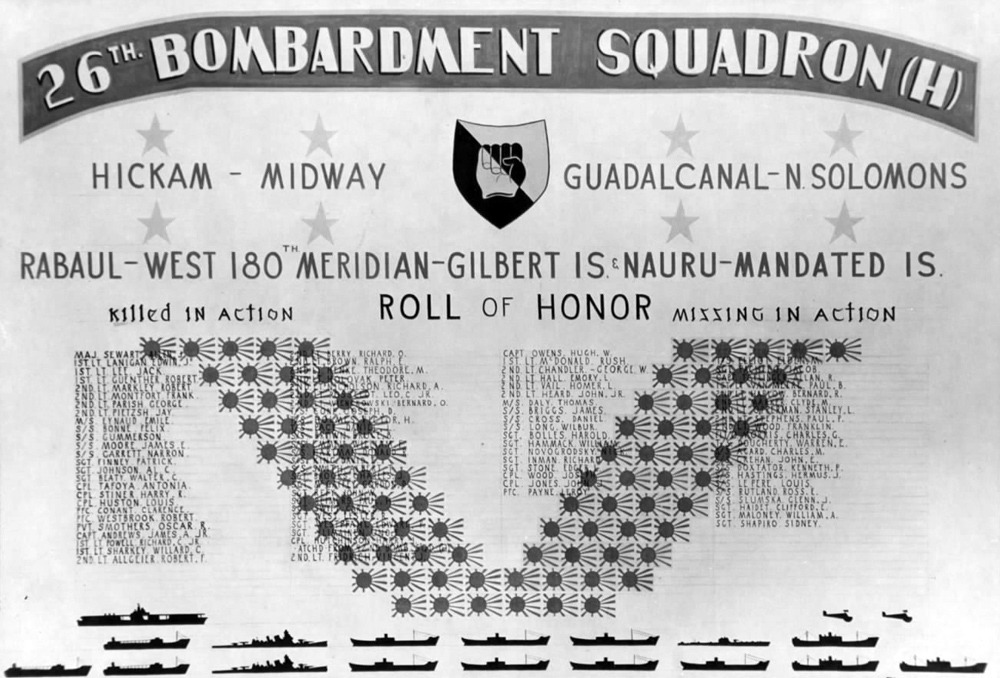

| Pacific | 26th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 11th Bombardment Group (Heavy) |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters, Purple Heart?, Good Conduct Medal | Pacific air campaign |

| Military Occupational Specialty (Presumed) | Entered the Service From |

| 612 (airplane armorer/gunner) | Ocean City, Maryland, or Laurel, Delaware |

Early Life & Family

Hermus Jackson Hastings was born on Market Street in Laurel, Delaware, on the morning of February 15, 1923. He was the second child of Hermus Ralph Hastings (then a laborer, 1900–1950) and Gladys Jackson Hastings (née Gladys Mae Jackson, 1901–1986). Census records suggest he went by his middle name, at least as a youth. As a young adult, he was nicknamed Jack.

Hastings had an older sister, Adline Jane Hastings (1920–1927), and two younger brothers: Charles Ralph Hastings (1925–2003, who served in the U.S. Navy during World War II) and Frederick Seth Hastings (1928–1999).

Hastings and his family may have briefly moved to central Pennsylvania, since his younger brother, Charles, was born in Paxtang, near Harrisburg, on October 4, 1925. If so, the family soon returned to Laurel. On March 18, 1927, tragedy struck when Hastings’s older sister, Adline, was struck and killed by an automobile on Central Avenue near 8th Street in Laurel. She was just six years old.

Hastings was recorded on the census in April 1930, living on West Street in Laurel with his parents, two younger brothers, and his paternal grandmother. His father was listed as a trucker for a produce company.

According to census records, the Hastings family was living in Raeford, North Carolina, as of April 1, 1935. By the time of the next census, recorded in April 1940, Hastings was living with his family on Baltimore Avenue in Ocean City, Worcester County, Maryland. Hastings had completed three years of high school and was working part-time as a grocery store clerk. He had worked 16 hours during the week of March 24–30, 1940. At the time, his father was a distributor for a newspaper agency. It appears that the younger Hastings also worked as a paperboy for The Salisbury Times, which described him as a “former Times carrier[.]”

The Salisbury Times and Journal-Every Evening both reported that after Hastings graduated from Ocean City High School, he attended Beacom College in Wilmington, Delaware. His enlistment data card described him as a high school graduate. If accurate, that may indicate that he dropped out of college before finishing his freshman year. However, several other soldiers from Delaware who were reported to have attended Beacom also had enlistment data cards which described their highest education level as high school.

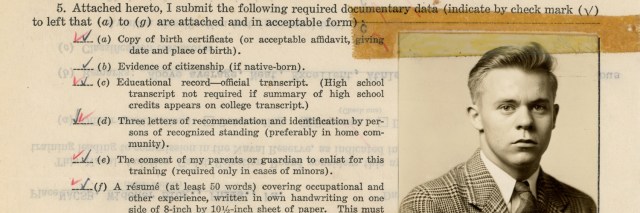

Hastings began working for the DuPont nylon factory in Seaford, Delaware, on March 17, 1941. When he registered for the draft in June 1942, Hastings was living on Central Avenue in Laurel. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, 11½ inches tall and weighing 150 lbs., with brown hair and gray eyes. On the other hand, his individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) described him as standing five feet, nine inches tall and weighing 144 lbs., with brown hair and hazel eyes.

It appears that Hastings moved back to Ocean City before entering the service. At the very least, he gave Worcester County, Maryland, as his residence at enlistment, or the Army considered it his permeant address since his parents lived there. An Army Air Forces award card listed Ocean City, Maryland, as the place he entered the service from, but also cross-referenced Laurel, Delaware. Hastings’s enlistment data card described him as a machinist. He was Presbyterian according to Young American Patriots.

Military Career

Hastings volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Forces, enlisting as a private in Baltimore, Maryland, on October 27, 1942. The July 1944 issue of Threadline, a newsletter from the DuPont Seaford factory, stated that Hastings “completed his basic training at Atlantic City and graduated from flexible gunnery school at Fort Myers, Florida.” The article added that Hastings “graduated from Armorer’s School at Lowry Field, California [sic], and left the United States for Hawaii from where he went to the Gilbert Islands.”

Young American Patriots stated that Hastings went on active duty at Camp Lee, Virginia. He trained at Atlantic City, New Jersey; Fort Myers, Florida; Lowry Field, Colorado; and Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.

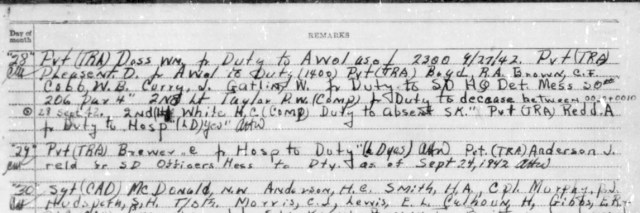

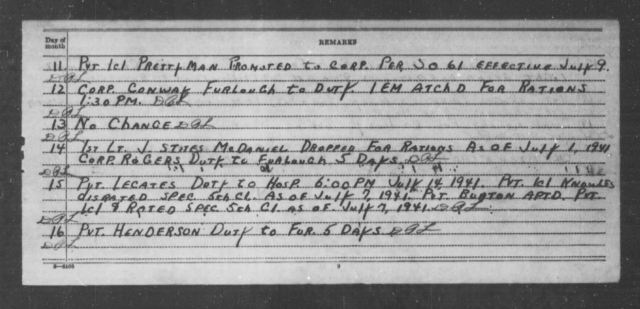

A document in Hastings’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) establishes that as of May 10, 1943, Sergeant Hastings was with the 30th Training Group at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. Another document from about a month later stated that he was with the 21st Technical School Squadron at Lowry Field, Colorado.

Journal-Every Evening reported on February 13, 1943, that Hastings had recently been promoted to sergeant after completing flexible gunnery school at Fort Myers, graduating “on the honor roll, being one of the top 20 in a class of 300.” When the article was printed, he was enrolled in a 10-week armorer’s school at Lowry Field. The Salisbury Times reported that Hastings turned down an offer to stay at Fort Myers as an instructor.

The Salisbury Times reported that Hastings became a waist gunner and went overseas on June 5, 1943. He joined 26th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 11th Bombardment Group (Heavy), Seventh Air Force, probably at Wheeler Field, Hawaii. The unit had flown Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses in the South Pacific early in the war, but recently returned to Hawaii to reequip with Consolidated B-24 Liberators.

The Salisbury Times reported on August 31, 1943, that Sergeant Hastings had survived a raid on Japanese-occupied Wake Island and witnessed the destruction of an enemy fighter:

Sgt. Hastings, an aerial gunner of a Liberator crew, saw the Zero burst into flames about 100 yards away. “I think one of our gunners got him. You could see the flames and smoke as the Zero flashed by,” he said.

The Liberators engaged in a nearly 50 minutes running flight with 15 to 20 Zeroes. Despite the Japanese fighters and heavy anti-aircraft fire, the bombs carried by the Liberator were dropped on their designated targets.

Wake Island was an American possession that had fallen to the Japanese shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The raid in question almost certainly took place on July 26, 1943, involving 12 B-24s from the 11th Bomb Group including four from the 26th Bomb Squadron. One flown by Lieutenant Allan R. Taflinger (1916–1944), who Hastings flew with on his final mission, dropped six general purpose bombs which landed in the water without observed effect. Various crews involved in the mission reported seeing between nine and 20 enemy fighters. Enemy fighters made multiple passes at Taflinger’s plane and the B-24 took hits in the bomb bay and rudder. Their flight lasted six hours and 40 minutes. The B-24 crews claimed 11 enemy fighters shot down, eight probably shot down, and 11 damaged, with Taflinger’s crew claiming one shot down and one probable. (Of course, the claims exceeded the total number of aircraft reported by any of the crews. American bomber gunners were notorious for overclaiming victories over attacking fighters, since several gunners often fired at and claimed the same aircraft, and not every fighter that peeled off with apparent damage actually crashed.)

Hastings was promoted to staff sergeant on October 5, 1943.

Though most of the 11th Bomb Group began moving to Funafuti, Ellice Islands (present day Tuvalu), in October 1943, the 26th Bomb Squadron was temporarily based on another island, Canton, in the Phoenix Islands (now part of the Republic of Kiribati). A 26th Bomb Squadron history stated that most of the air echelon of the squadron arrived at Canton on September 15, 1943. Six B-24s from the squadron flew a single mission against Betio, Tarawa Atoll, Gilbert Islands (now also part of the Republic of Kiribati), but soon returned to Wheeler Field. The squadron returned to Canton in November. Curiously, the ground echelon moved not to Canton but to Nukufetau (now part of Tuvalu), another island to the west, arriving on November 11, 1943. They worked on U.S. Navy aircraft from VB-108 there. The squadron was reunited at Nukufetau on December 31, 1943.

The 11th Bomb Group launched raids on Japanese-held islands in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands before and during the Battle of Tarawa. According to a group history, “The mission of the 11th Group in the island campaigns has been the neutralization of enemy airfields.” On January 20, 1944, the ground echelon of the 26th Bomb Squadron boarded U.S.S. LST-20, arriving four days later at Buota, Tarawa Atoll. The air echelon moved to Buota or Betio on January 23, 1944. The group supported the capture of the Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands, and then moved there in March 1944. Eniwetok Atoll (Enewetak Atoll), also in the Marshall Islands, was used as a staging base for raids against the major Japanese base at Truk Atoll (present day Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia), beginning on March 27, 1944. Earlier in the war, Truk had been one of the main Japanese bases in the Central Pacific. Rather than invade, the U.S. Navy smashed the base and the ships stationed there with carrier aircraft and battleships during a raid on February 17, 1944. Though the Allies bypassed the base without invading it, they kept the pressure up to prevent the Japanese from restoring its capabilities as the Allied drive toward Japan continued.

Aircrew losses in the Pacific were not as heavy as in Europe. However, crews aboard planes that went down in the vast ocean or on Japanese-held islands had a much lower chance of survival as those shot down over Europe. According to a report attached to a squadron history, between March 13, 1944, and May 1, 1944, the average 26th Bomb Squadron combat mission entailed flying 1,928 statute miles roundtrip with an average of 11.9 hours in the air. As of April 1944, 26th Bomb Squadron crews had to complete 30 combat missions before being rotated back to the United States.

A group history stated that the men’s health was generally good, though it noted:

In these campaigns the wearying and inevitable round of C Rations and Vienna Sausages and Spam has been the factor which has affected morale. The cooks have worked very hard to disguise these materials and have taken incredible pains to do the best job possible.

Hastings and 12 other enlisted men were awarded the Air Medal and one oak leaf cluster in lieu of a second medal per General Orders No. 27, Headquarters Seven Air Force, dated March 19, 1944. The citation stated that “Each, as a crew member of a bombardment type aircraft, participated in ten (10) strike sorties against the enemy, displaying high professional skill, courage, and devotion to duty which reflected great credit upon himself and the Army Air Forces[.]”

According to an 11th Bomb Group history for April 1944:

On 1 April the air echelon of the 11th Group was temporarily based at Eniwetok while the ground echelon was aboard an LST headed for Kwajalein. […]

The Group was operating under extreme difficulties. Strikes were being flown against Truk every day by this Group and the 30th Group combined. Two squadrons from the 11th Group would hit one night. One squadron of the 11th with one squadron of the 30th would hit the next night. On the third night two squadrons from the 30th would strike. Since the field at Eniwetok could only care for two squadrons of B-24s at a time it necessitated shifting the squadrons back and forth so that no one squadron would have two strikes in a row. The air echelons of the squadrons were also orphans as their ground echelons were also on the high seas aboard LSTs. […]

The defenses of Truk Islands were not as strong as had been expected and our Group had suffered no damage up to this time. Truk was struck on the night of 2 April 1944 local time with 13 B-24s from the 431st Squadron and again on the night of 3 April 1944 local time with 21 B-24s from the 26th and the 98th Squadrons. All returned without casualties or damage.

Final Mission

On April 4, 1944, Staff Sergeant Hastings was a gunner in a crew that took off from Eniwetok aboard B-24J 42-100394, piloted by Captain Taflinger and Flight Officer Charles Granville Morris (1919–1944), for a strike on the Truk Atoll.

Per Field Order 44-34, three flights of aircraft from the 26th Bomb Squadron, with three aircraft each, would take off at 15-minute intervals starting at 0700 hours Greenwich Civil Time, about 1900 hours local time. Each plane would be armed with 12 500 lb. general purpose bombs.

According to the 11th Bomb Group history:

On the night of 4 April 1944 local time the 26th Squadron sent eight planes over Truk. One of these bombed the alternate target of Ponape due to engine trouble. Two of the airplanes failed to return from this mission. They were last seen by other crews over the target and from interrogation it appears that they blew up over the reef east of Dublon.

The group war diary stated:

In accordance with Field Order # 44-34 10 B-24 airplanes of the 26th Squadron were assigned to make a night bombing strike against targets on Truk Islands. One plane due to engine trouble bombed Ponape. The seven planes over Truk dropped 21 tons of 500 pound GP [general purpose] bombs with 100 percent hitting on land. 4 large fires were started in the [fuel] tank farm area on Dublon Island which were visible for 75 miles at 10,000 feet. […] Our planes were intercepted by 2 night fighters each of which was destroyed by our gunners. Two of our planes failed to return from the mission. They were last seen by other crews over the target. One crew reported seeing a plane in flames over the reef at Truk and tracers coming out of the fire. The burning plane dropped and broke in 3 places continuing to burn on the water. About 10 minutes later, this crew also saw what appeared to be a plane on fire which disappeared into a cloud.

1st Lieutenant Hayden E. Weaver, another member of the squadron, made a statement soon after the mission: “Four minutes before CAPT TAFLINGER’S ship was observed on fire, we were flying on a heading of North, paralleling the reef of Truk Atoll. We spotted our target and decided to break formation to bomb same.”

Weaver radioed Taflinger’s plane and received an acknowledgment. Minutes later, Taflinger’s B-24 was observed on fire. Weaver’s crew was unable to raise them on the radio. The B-24 and the 10 men aboard were never seen again.

According to Missing Air Crew Report No. 3876, Hastings’s plane was last seen 10 miles northeast of Dublon (Tonowas) at 1145 hours Zebra Time (around 2145 hours local time). The Salisbury Times reported that Hastings’s mother learned that her son was missing in action on her birthday.

Weaver’s initial statement did not mention any midair explosion and an April 1945 review summarizing the case did not mention either of the two lost B-24s exploding. Investigators contacted Weaver again after the war and he provided more detailed information which explicitly linked Captain Taflinger’s B-24 with the one that exploded, though he questioned the accuracy of the claim that it was last seen 10 miles from Dublon:

The plane exploded in the air a short distance off my right wing, and it fell in three sections. […] [W]e were headed westerly on our bomb-run when we noticed his plane on fire. His plane kept turning to the left and we had to turn in a southerly direction to prevent collision. I believe that we were both headed back in an easterly direction by the time the explosion occurred. It seems to me that the crash was very near the reef….I would not say whether it was inside or outside the reef. As near as I could fix the scene of the crash would be along the eastern most point of the reef.

Available documentation does not indicate whether the plane was brought down by enemy fighters, antiaircraft fire, or mechanical trouble.

While he was still considered missing in action, Staff Sergeant Hastings was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross per General Orders No. 59, Headquarters Seventh Air Force, dated May 17, 1944. He was also awarded a second oak leaf cluster for his Air Medal per Special Orders No. 79, Headquarters Seventh Air Force, dated June 16, 1944.

Hastings’s personal effects included an identification bracelet, a pair of gunner’s wings, a scrapbook, his birth certificate, and an envelope of letters recommending him for Officer Candidate School (O.C.S.).

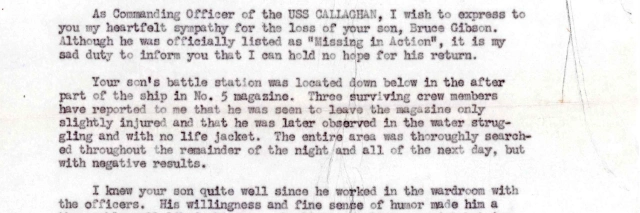

There is no indication that Staff Sergeant Hastings survived the crash. However, investigators later learned a detail that added to the mystery: “An unofficial report obtained from captured Japanese documents indicate that Lt Van Metre was a prisoner of war at Truk (Casualty Branch Message Number 362196).” However, 1st Lieutenant Paul B. Van Metre (1917–c. 1944), the crew’s navigator, was not discovered alive as a prisoner after the Japanese surrendered in 1945.

In 1947, several Imperial Japanese Navy servicemen, including the commanding officer of the 4th Naval Hospital on Dublon, Surgeon Captain Iwanami Hiroshi, were convicted of involvement in a series of war crimes in 1944 in which 10 American prisoners were brutally murdered. Several additional suspects committed suicide before the trial. Eight of the victims were killed prior to the raid where Staff Sergeant Hastings and his crew went missing. The last two victims were two men who Iwanami ordered his staff to kill with bayonets, spears, and swords on July 20, 1944. The specific identities of the prisoners were not determined beyond that they were American airmen. While Americans captured by the Germans were typically reported as prisoners of war through the International Red Cross, the Japanese military often did not report theirs, making it difficult to determine which missing airmen they were. (For the same reason, the War Department delayed issuing a finding of death for Staff Sergeant Hastings until February 15, 1946, not the more common year and a day.)

The Japanese justification for the last two murders was that American air raids several days earlier had struck the hospital. Iwanami was executed by hanging in 1949. A memorandum that same year summarizing an investigation by Elizabeth A. Ridgway speculated that if Lieutenant Van Metre was indeed captured, he was one of the two victims of the July 1944 incident.

During his career, Staff Sergeant Hastings earned the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters, the Good Conduct Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with five bronze service stars. Although death during a combat mission typically resulted in aircrew being awarded the Purple Heart, there was no award card for that decoration on file in the National Archives and his mother did not mention it in a 1947 letter which mentioned other medals.

Staff Sergeant Hastings is honored on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii and on a memorial marker at Odd Fellows Cemetery in Laurel, where his parents and older sister are buried. Because records indicated that he entered the service from Maryland, Hastings’s name was omitted from Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware. However, his name is honored at the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii and on a plaque formerly displayed at the DuPont factory and now in the collection of the Seaford Museum.

Crew of B-24J 42-100394 on April 4, 1944

The following list is based on Missing Air Crew Report No. 3876, with grade, name, service number, position. All ten men were killed in action or, in the case of Lieutenant Van Metre, possibly killed as a prisoner of war.

Captain Allan R. Taflinger, O-442559 (pilot)

Flight Officer Charles G. Morris, T-1896 (copilot)

1st Lieutenant Paul B. Van Metre, O-2045296 (navigator)

2nd Lieutenant Bernard C. Harlow, O-733561 (bombardier)

Staff Sergeant Charles M. Agard, 16013994 (engineer)

Staff Sergeant John E. Crehan, 12026287 (assistant engineer)

Staff Sergeant Ross E. Rutland, 37211160 (radio operator)

Staff Sergeant Warren E. Dougherty, 32412069 (radar operator)

Staff Sergeant Kenneth P. Doxtator, 16022861 (gunner)

Staff Sergeant Hermus J. Hastings, 13135889 (gunner)

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jim Bowden for providing the Threadline issue which mentioned Staff Sergeant Hastings, who had not originally been on my list of Delaware fallen.

Bibliography

Air Medal Decoration Card for Hermus J. Hastings. Award Cards, 1942–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139447754?objectPage=860

“Bombing of Wake Island.” August 4, 1943. Reel A7609. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Case of Hiroshi Iwanami.” 1947. Case Files, 1944–1949. Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), 1792–2010. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6997428

Census Record for H. Jackson Hastings. April 13, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89M1-ZNJ6

Census Record for Jackson H. Hastings. April 25, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR48-CV

Certificate of Birth for Frederick Seth Hastings. Undated, c. April 16, 1928. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YQM-Q2FN

Certificate of Birth for Hermus Jackson Hastings. February 15, 1923. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-D4FS-4NN

Certificate of Death for Adline Jane Hastings. March 18, 1927. Delaware Death Records. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D159-BVP

“Delawareans in the Service.” Journal-Every Evening, February 13, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136903542/

Distinguished Flying Cross Award Card for Hermus J. Hastings. Award Cards, 1942–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/133384640?objectPage=91, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/133384640?objectPage=92

Draft Registration Card for Charles Ralph Hastings. February 25, 1946. WWII Draft Registration Cards for Maryland, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44015_11_00017-00338

Draft Registration Card for Hermus Jackson Hastings. June 1942. WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_08_00003-01645

Enlistment Record for Hermus J. Hastings. October 27, 1942. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=13135889&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=769496

“Field Order 44-34.” April 4, 1944. Reel B0067. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Flier Missing Soon After Getting DFC.” The Salisbury Times, May 16, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136910192/

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Hermus J. Hastings. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Paul B. Van Metre. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

“Japanese Doctor Hanged on Guam.” The Press Democrat, January 19, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-press-democrat-iwanami-hung/153660799/

McGreevy, Wallace F. “Missing Air Crew Report No. 3876.” April 5, 1944. Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRs), 1942–1947. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. The National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/90948822

“Military News and Pictures.” Threadline, July 1944. Courtesy of Jim Bowden.

Morning Report for 26th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 11th Bombardment Group (Heavy). October 5, 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/454068694?objectPage=25

“Narrative of Group History 1 April to 30 April 1944.” May 9, 1944. Reel B0067. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Ocean City Hero Missing In Pacific Soon After Decoration.” The Salisbury Times, May 11, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136910758/

“Organizational History, 26th Bombardment Squadron (H) 7th Bomber Command, Seventh Air Force. April 1, 1944 —- April 30, 1944.” Reel A0544. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Organizational History, Headquarters 11th bombardment Group (H), VII Bomber Command, Seventh Air Force.” Reel B0067. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Shore Gunner Saw Zero Shot Down.” The Salisbury Times, August 31, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136904575/

“Two Shoremen Decorated Posthumously.” The Salisbury Times, March 13, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/136907519/

Young American Patriots: The Youth of Maryland and Delaware in World War II. National Publishers, Inc., 1950. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8941/images/md_de1-0363

Last updated on October 20, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.