| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Recent graduate |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 12211870 |

| Theater | Unit |

| European | Company “E,” 104th Infantry Regiment, 26th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 746 (automatic rifleman) | Rhineland campaign |

| Awards | Entered the Service From |

| Silver Star, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge | Edgewood Hills, Delaware |

Early Life & Family

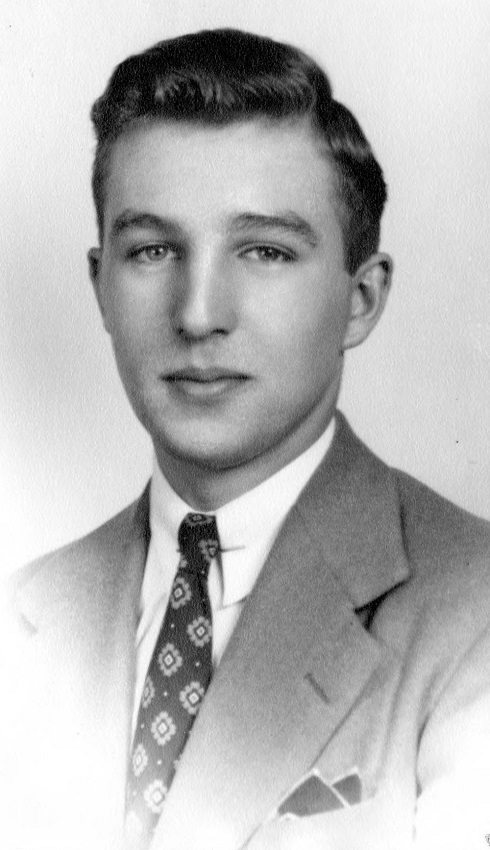

Wallace Steuart Wroten, Jr. was born at the Delaware Hospital in Wilmington, Delaware, on the evening of June 6, 1925. He was the only child of Wallace Steuart Wroten, Sr. (1894–1967), and Anna M. Wroten (née Anna May or Mae Horsey, 1894–1925).

When he was born, Wroten’s parents were residents of 806 West Street in Wilmington. His mother developed a postpartum infection, leading to sepsis and her death at the Delaware Hospital on June 15, 1925.

During World War I, Wroten’s father had served in the U.S. Army’s 20th Engineers, a forestry unit that operated in France. The elder Wroten worked as an accountant and later as a control manager in the Advertising Department at the Du Pont Company. Wroten was raised by his father and his stepmother, Nellie Wroten (née Nellie Marie Clopein, 1904–1990), who his father married in Wilmington on May 28, 1927.

On November 14, 1929, Wroten’s father and stepmother purchased a home at 215 West 35th Street in Wilmington, where the family was recorded living during the 1930 and 1940 censuses. The 1930 census listed him as Wallie Wroten, suggesting that was his nickname. On November 25, 1940, Wroten’s father and stepmother purchased a property at 181 Brandywine Boulevard in Edgewood Hills, northeast of Wilmington.

In a 1949 letter to Secretary of State George C. Marshall (1880–1959), Wroten’s father described his son:

He was an outstanding youth leader in Wilmington, Pres. of the Student Council in Delaware’s leading high school, Pres. of the Young Peoples Choir in one of the largest churches, and officer of the Hi-Y Club of the YMCA and active in Boy Scout affairs.

Wroten attended Warner Junior High School and later graduated from Pierre S. duPont High School in June 1943. He was Protestant.

Military Training

At the end of 1942, most voluntary enlistments in the American armed forces ended under an executive order from President Roosevelt. As a result, most of the military’s manpower was selected by local draft boards for the duration of the war. Some exceptions to the order existed and 17-year-olds could still volunteer. The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps had already recruited 17-year-olds before the order. Facing the prospect of the other services recruiting the most eager and fit young men before they could be drafted, the U.S. Army belatedly began recruiting 17-year-olds as well, though these youths were not called up for active duty until they turned 18. One potential recruiting angle was the Army Specialized Training Program (A.S.T.P.). Soldiers who passed a challenging test and who were selected the program attended accelerated college classes, studying subjects like languages and engineering that would make them a resource to the Army after graduation.

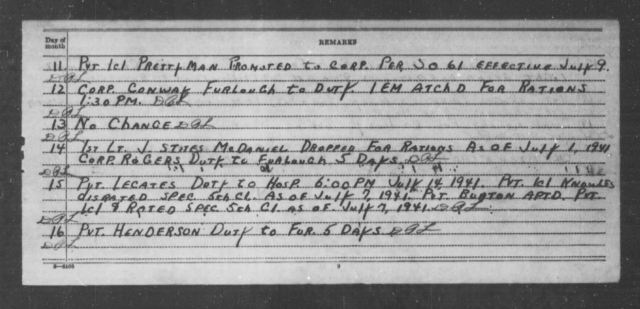

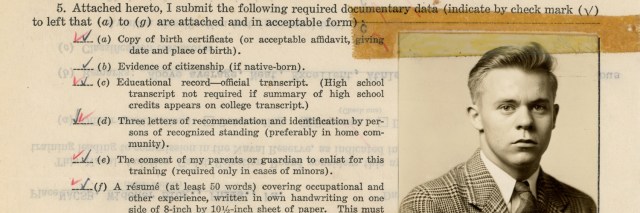

On May 28, 1943, shortly before he graduated high school, Wroten enlisted in the U.S. Army’s Enlisted Reserve Corps. His father indicated that Wroten passed the A.S.T.P. test while in high school. After he turned 18, Private Wroten went on active duty at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on July 19, 1943. Most Delawareans who joined the Army during World War II spent about a week to 10 days at the reception center there before continuing their training elsewhere. It appears that Private Wroten spent a little longer there than most men. On August 28, 1943, he was assigned to the Infantry and transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia. He began the 13-week basic training course on September 4, 1943. During his training, Private Wroten learned to use and fire multiple weapons and qualified at the sharpshooter level with the M1 Garand rifle.

Wroten graduated from basic training on December 4, 1943. Three days later, he was transferred to A.S.T.P. at the University of Maine. Journal-Every Evening reported that Wroten “studied electrical engineering” there. In the long term, the program had the promise of graduating men with valuable skills. Unfortunately, with the U.S. Army already suffering high casualties in the Mediterranean and Pacific Theaters and a new front about to open in northwest Europe, planners began to rethink the commitment of thousands of the Army’s brightest young men to the classroom rather than the battlefield.

In the last weeks of A.S.T.P., tragedy struck some of the members of the program at the University of Maine. In the early morning hours of February 13, 1944, fire swept through the north wing of Hannibal Hamlin Hall in Orono, Maine, which 73 A.S.T.P. men called home. Two soldiers were killed, including a Delawarean, Private Thomas Marvel Gooden, III (1922–1944), and several more were severely injured. Many A.S.T.P. men from other dormitories rushed to the scene to assist the firemen and treat the injured, though it is unknown if Wroten was among them.

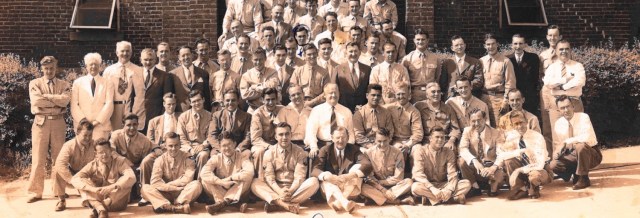

On March 11, 1944, after A.S.T.P. was terminated, Private Wroten was transferred to Company “E,” 104th Infantry Regiment, 26th Infantry Division. His unit was in the middle of training at the Tennessee Maneuver Area. His regiment had spent the early years of the war training and performing guard duty. At the end of 1943, hundreds of men were stripped to go overseas as replacements, creating openings that the infusion of A.S.T.P. men like Wroten helped fill. The training had hazards. On the night of March 22, 1944, 21 men drowned in the Cumberland River, including a Delawarean, Sergeant John J. Paisley (1920–1944), after their boat overturned. Following the end of maneuvers, the 104th Infantry moved to Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

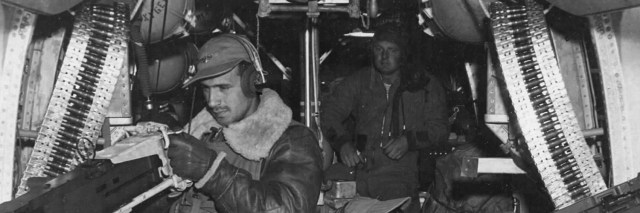

At Fort Jackson, Private Wroten performed additional weapons training, requalifying with the M1 rifle on April 12, 1944. Soon after, he qualified at the expert level with the Browning Automatic Rifle (B.A.R.). Developed during World War I, the B.A.R. was a heavy but popular weapon. It was the heaviest weapon in an Army rifle squad, though with its 20-round magazine, the B.A.R. could not match the firepower of the machine guns that the Germans equipped their squads with. Given the skill he had demonstrated by qualifying with the B.A.R. at the highest possible level, it is no surprise that by the time he entered combat, Private 1st Class Wroten’s military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) was 746, automatic rifleman.

Wroten was promoted to private 1st class on April 16, 1944. In mid-May 1944, he trained with hand and rifle grenades. He completed a night infiltration course on May 23, 1944, and the following day attended an urban combat class.

In late-August 1944, the 104th Infantry moved to Camp Shanks, New York, a staging area for the New York Port of Embarkation. The regiment shipped out aboard the troopship S.S. Argentina on August 27, 1944.

Combat in the European Theater

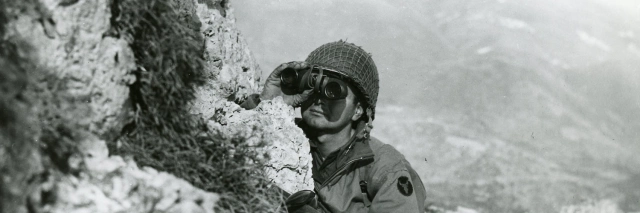

The 104th Infantry Regiment arrived in Cherbourg, France, on September 7, 1944. By that time, the Germans had been driven out of most of France, but Allied momentum slowed as supply lines became increasingly long. On October 4, 1944, the regiment began moving east across France by truck, soon arriving at the front lines in Lorraine. Private 1st Class Wroten’s 2nd Battalion went into the line on the night of October 6–7, 1944, as the 104th Infantry relieved elements of the 4th Armored Division.

A history book printed at the end of the war, History of a Combat Regiment 1639–1945 104th Infantry, stated: “The 104th, on orders from Corps, was to clear the enemy from Moncourt Woods and Bezange La Petite, thereby straightening the line and removing threats to its positions.” On the morning of October 10, 1944, Company “C” was repulsed during an attempt to take the top of “Hill 264.8 east of Bezange La Petite.” The history continued:

What was left of the attacking force withdrew to the reverse slope of the hill and dug in. At 1600, Co. E, commanded by Capt. Leo Monnin, was ordered up to take over these positions and remained there until relieved by the 101st Infantry Regiment on October 18. The enemy remained entrenched on the hilltop until the big Allied offensive in November.

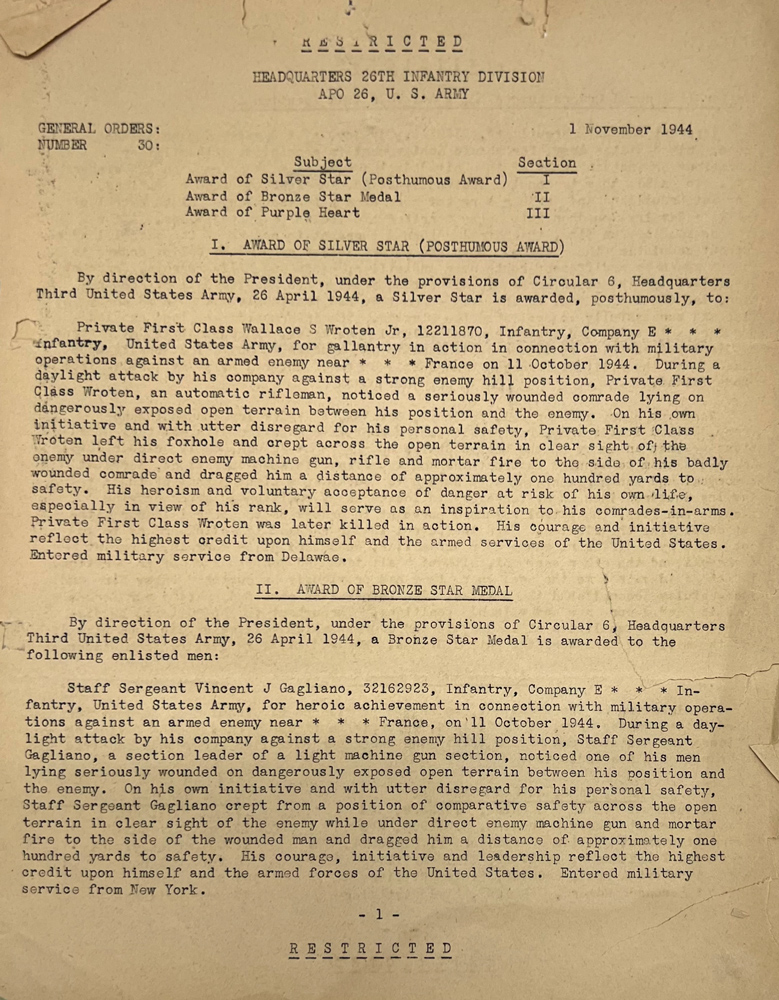

Early in his combat career, Private 1st Class Wroten performed actions that earned him the Silver Star per General Orders No. 30, Headquarters 26th Infantry Division, dated November 1, 1944. The citation stated in part:

During a daylight attack by his company against a strong enemy hill position, Private First Class Wroten, an automatic rifleman, noticed a seriously wounded comrade lying on dangerously exposed open terrain between his position and the enemy. On his own initiative and with utter disregard for his personal safety, Private First Class Wroten left his foxhole and crept across the open terrain in clear sight of the enemy under direct enemy machine gun, rifle and mortar fire to the side of his badly wounded comrade and dragged him a distance of approximately one hundred yards to safety. His heroism and voluntary acceptance of danger at risk of his own life, especially in view of his rank, will serve as an inspiration to his comrades-in-arms.

The date of the rescue was listed in the citation as October 11, 1944. Oddly, History of a Combat Regiment suggested the line was static at that point, possibly making the events of the previous day a better fit. Unfortunately, virtually all 104th Infantry textual records from the fall of 1944 are missing from the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, or were not preserved, making it difficult to contextualize the events surrounding Wroten’s heroic act.

Another curious detail is that General Orders No. 30 also awarded the Bronze Star Medal to Staff Sergeant Vincent J. Gagliano (1918–1997), another member of Company “E,” for actions on October 11, 1944, with nearly identical wording to Wroten’s citation:

During a daylight attack by his company against a strong enemy hill position, Staff Sergeant Gagliano, a section leader of a light machine gun section, noticed one of his men lying seriously wounded on dangerously exposed open terrain between his position and the enemy. On his own initiative and with utter disregard for his personal safety, Staff Sergeant Gagliano crept from a position of comparative safety across the open terrain in clear sight of the enemy while under direct enemy machine gun and mortar fire to the side of the wounded man and dragged him a distance of approximately one hundred yards to safety.

It is unclear from the citations if Wroten and Gagliano worked together to rescue one of Gagliano’s men, or whether Wroten had rescued another wounded comrade under similar circumstances.

Journal-Every Evening summarized a letter that Private 1st Class Wroten had written on October 18, 1944:

In this letter he said that he had been made a sergeant, thus fulfilling one of his ambitions. The young soldier said that now he would be able to compare battle experiences with his father for he had come through his first major battle action without a scratch.

Subsequent evidence indicates the Wroten had been recommended for promotion to sergeant and was acting in that capacity but that the promotion had not been confirmed by higher headquarters. Under the tables or organization, B.A.R. gunners were not supposed to be noncommissioned officers, suggesting that Wroten was acting as an assistant squad leader in his rifle squad.

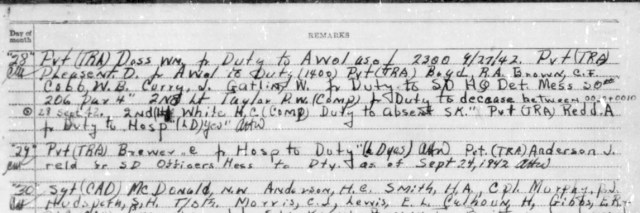

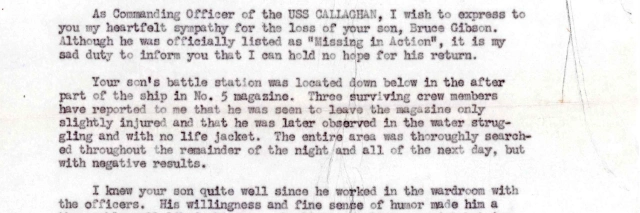

After days of artillery and tactical airstrikes had softened up the German positions, the 104th Infantry resumed its attack on October 22, 1944. Initially, Company “E” was held in reserve while 1st Battalion made some modest gains, but “was committed at noon to support Co. F on the right. […] At approximately 1450, Co. E was pinned down by automatic-weapons fire from Moncourt Woods.” Private 1st Class Wroten was reported as killed in action near Bezange-la-Grande on October 24, 1944, after he was struck in the chest by an artillery shell fragment. He was initially buried at a military cemetery in Andilly, France, on October 26, 1944. Wroten’s personnel effects included a ring, 20 photos, his Social Security card, a billfold, two letters, and a pair of swim trunks.

A Grieving Family

Wroten’s father and stepmother were notified on November 1, 1944, that he was missing in action as of October 18, 1944. Five days later, friends told them that a Baltimore newspaper article had disclosed that he had been awarded the Silver Star as well as his later death in combat on October 24, 1944. Despite frantic efforts by the Wrotens to verify the news, it was only on November 8, 1944, that the War Department confirmed Private 1st Class Wroten’s death.

On December 10, 1944, an excerpt of Wroten’s Silver Star citation was printed in a minor Wilmington newspaper, The Sunday Morning Star, though the citation had not yet been sent to his parents. The following day, Wroten’s father wrote to Senator Clayton Douglass Buck, Sr. (1890–1965), sarcastically remarking: “I suppose we should feel encouraged by the improvement in the War Department’s reporting. Although we still must get our information through the newspapers, the latest report did get published in the right city.” He complained that his son and the other A.S.T.P. men “were earmarked as ‘cannon fodder’” when the program ended.

A March 16, 1945, letter from the Adjutant General’s Office to Wroten’s father preserved in Wroten’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) was unable to explain the discrepancy that placed Wroten as either missing in action on October 18, 1944, or killed in action on October 24, 1944. However, the letter stated:

The report continues with the statement that his death occurred as a result of a shrapnel wound to the chest, sustained while actively engaged against the enemy at Bezange-la-Petite, near Rechicourt, France, on 24 October 1944. The record confirms his grade as Private First Class, acting as Sergeant, and his advancement in grade was under consideration at that time.

After the war, on September 8, 1947, Wroten’s father initially requested that his son’s body be permanently reburied overseas, angrily adding:

Please try to bury the right body in the grave of our only child & don’t bungle it like you did everything else and don’t publish the fact in some Baltimore newspaper—as his death was published—before we were notified.

The elder Wroten came to regret that decision, and as time passed, he continued to brood on the circumstances leading to his son’s death. Finally, on January 1, 1949, Wroten’s father wrote a furious letter to Secretary of State George C. Marshall (1880–1959), who had been the Army chief of staff during World War II. The elder Wroten described his son:

He was one of those carefully selected young high school graduates who was deceived into enlisting (age 17) in the ASTP, on your specific written promise that he would be given up to eighteen months of specialized college training, and an opportunity to qualify for Officer Candidate School. […]

He was an outstanding youth leader in Wilmington, Pres. of the Student Council in Delaware’s leading high school, Pres. of the Young Peoples Choir in one of the largest churches, and officer of the Hi-Y Club of the YMCA and active in Boy Scout affairs. Apparently these leadership traits qualified him only for the Infantry, generally regarded as the lowest form of Army life and almost certain death.

Wroten’s father wrote of his son: “With practically no training, he was rushed to France and directly into combat[.]” He complained that during his brief time in combat, his son had earned not only the Silver Star but a promotion to the grade of sergeant, but “since he died so soon after his act of bravery, the Army decided not to confirm the promotion which he gave his life to earn.” He raged about the fact that he and his wife had learned of Wroten’s death when friends read about it in a Baltimore newspaper before the War Department told the family directly. He added: “This boy was our whole world, and we too died inside when he was killed. The horrible Army treatment and brutal disregard for all common decencies has wrecked our health and our way of life.”

Finally, Wroten’s father requested that the form he submitted requesting that his son’s body be interred permanently overseas be disregarded and that he be repatriated for a private burial back in the United States.

Marshall had served as chief of staff of the largest Army ever assembled by the United States, with over 8,000,000 men and women in uniform at its maximum strength. Over 250,000 soldiers had died during the war or immediately afterward, a fact that undoubtedly weighed heavily on him. Beginning the process of responding to a soldier’s grieving father was one of the last pieces of business that Marshall handled as secretary of state. On January 6, 1949, he asked his assistant to have the Army research the accusations that the grieving father raised and prepare a draft for his review. He resigned as secretary of state the following day.

Although the text of the final letter Marshall sent is unknown, the nine-page draft finished by the staff of Brigadier General J. E. Moore (likely James Edward Moore, 1902–1986) around January 17, 1949, provided a great deal of detail about Wroten’s career, based on his personnel file. Addressing the decision to end A.S.T.P. and describing the extent of Wroten’s training in detail, the author disputed that Wroten had gone into combat inadequately trained:

All of the above described training was provided insofar as possible to every Infantry soldier, however, I must add that due to the exigencies of the service, thousands of young men who served in Infantry rifle companies entered into combat with far less preparation for the task they faced than your son received. I am sure you will agree with me that your son received the maximum account of preparatory training which the enlarged Army was capable of providing.

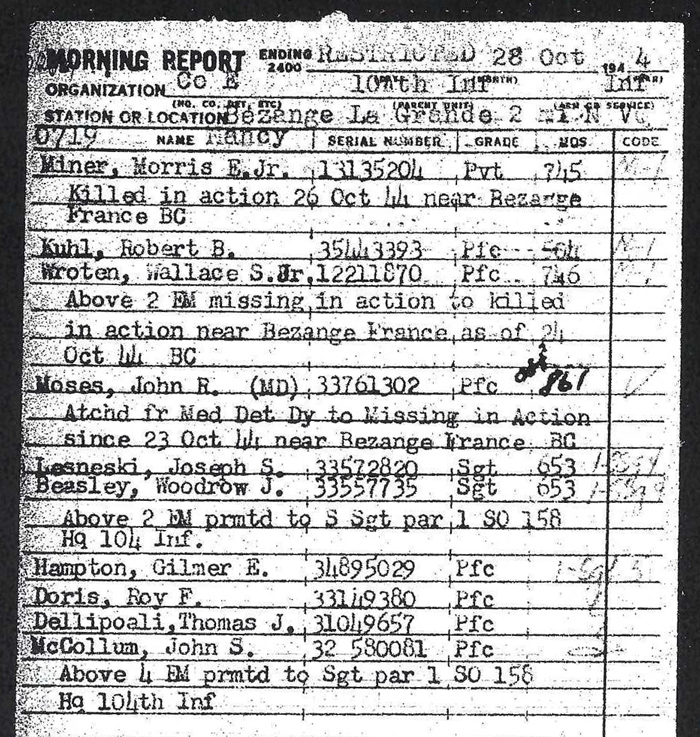

The letter explained that a war correspondent who learned of the posthumous Silver Star decoration prematurely revealed Wroten’s death before the Adjutant General’s Office had received notice. Indeed, although the October 28, 1944, Company “E” morning report recorded Wroten as killed in action on October 24, the Adjutant General’s Office in Washington, D.C., did not receive the report of death until November 7, 1944.

Regarding the promotion to sergeant, the research concluded that “According to the Army records, your son was performing the duties of a Sergeant in his Company at the time of his death.” Although posthumous promotions were rare during World War II, the author of the letter noted that it was permitted by law for specific circumstances if he was “officially recommended for promotion to a noncommissioned grade and who shall have been unable to receive or accept such promotion by reason of his death in line of duty.” Following an investigation by the Adjutant General’s Office, Wroten was posthumously promoted to sergeant. Marshall also intervened quickly to prevent Wroten’s body from being permanently interred overseas.

The extent to which Marshall’s letter assuaged Wroten’s father’s anger is unknown, though the final letter from elder Wroten preserved in Sergeant Wroten’s I.D.P.F., dated February 28, 1949, is notably less hostile than some of his previous letters. Wroten wrote to the Quartermaster Corps’ Memorial Division that he understood why regulations would not permit him to decline a military escort for his son’s casket on the final leg of its journey to Wilmington, explaining:

We are certainly not trying to be difficult. Instead, we want to have a very quiet and restricted re-burial. Our boy was very well and favorably known in Wilmington and his death brought about a great deal of publicity in the newspapers and elsewhere. We hope to avoid any repetition which would only be painful to us and to his many friends.

Sergeant Wroten’s body was disinterred and returned to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the Haiti Victory during the spring of 1949. On the morning of June 2, 1949, a military escort, Sergeant 1st Class Robert Edwin Mannon (1909–2005), himself a Delawarean, accompanied the casket to Wilmington by train. Wroten’s father told Sergeant Mannon that there was no need for him to attend the funeral. After services that afternoon, Sergeant Wroten was buried at Gracelawn Memorial Park in New Castle. His father and stepmother were also buried there after their deaths.

On June 3, 1949, the Wilmington Morning News announced:

This morning members of the 1943 class at the Pierre S. duPont School will honor Sergeant Wroten’s memory with the presentation of a silver trophy to the outstanding eleventh year student. The trophy will be awarded annually at the school to perpetuate the memory of Sergeant Wroten.

Sergeant Wroten’s decorations include the Silver Star, the Combat Infantryman Badge, and the Purple Heart. He is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Notes

Expert Infantryman Badge?

The report of death in Wroten’s individual deceased personnel file (I.D.P.F.) indicates that he earned the Expert Infantryman Badge (E.I.B.). A history book printed at the end of the war, History of a Combat Regiment 1639–1945 104th Infantry, stated:

At Fort Jackson, the regiment’s training reached its climax. Most of it centered around competition for the Expert Infantry Badge, a series of vigorous tests — obstacle courses, military and weapons-proficiency examinations, foot races, physical exercises, and a 25-mile hike — designed to show superior achievement and carrying a five-dollar raise in pay for successful candidates.

The service summary written at Marshall’s request does not mention the E.I.B. That suggests it was not mentioned in Wroten’s personnel file, since it would have been convincing evidence that he was not committed to combat with inadequate training. E.I.B.s were awarded to some men per General Orders Nos. 4–20, Headquarters 26th Infantry Division, but Wroten’s name was not among them. However, the division’s General Orders Nos. 21–28 from 1944 were not preserved in the National Archives, so it cannot be stated with certainty that Wroten was never awarded it.

The Baltimore Sun article

Journal-Every Evening named the war correspondent who prematurely disclosed Sergeant Wroten’s death as Lee McCardell (1901–1963) of The Baltimore Sun. I have been unable to locate the news item in either the evening or morning editions of the paper, although these editions did have other articles McCardell filed while observing the 26th Infantry Division.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for providing the morning report recording Wroten’s death and to the Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photo.

Bibliography

Application for Headstone or Marker for Wallace S. Wroten, Jr. June 6, 1949. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QV1Z-N1D3

Census Record for Wallace S. Wroten, Jr. April 15, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MR-M37B

Census Record for Wallie S. Wroten. April 3, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHM-X2M

Certificate of Birth for Wallace Steuart Wroten Jr. June 1925. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYQM-3Y1X

Certificate of Death for Anna Mae Wroten. June 15, 1925. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DRG9-M87

Certificate of Marriage for Wallace S. Wroten and Nellie Marie Clopein. May 28, 1927. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-X9DS-WL1

“City Infantryman Missing Sergeant Killed in Action.” Journal-Every Evening, November 9, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/80833937/

“City Sergeant Missing; Five Others Injured.” Journal-Every Evening, November 7, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/149439161/

Deed Between Harry B. Roos and Jechebeth T. Roos, Parties of the First Part, and Wallace S. Wroten and Nellie C. Wroten, Parties of the Second Part. November 14, 1929. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_257039-00140

Deed Between Harry R. Brown and Carmela T. Brown, Parties of the First Part, and Wallace S. Wroten and Nellie C. Wroten, Parties of the Second Part. November 25, 1940. Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_257101-00289

Enlistment Record for Wallace S. Wroten, Jr. May 28, 1943. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=929&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=12211870&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=70370

“General Orders Number 4, Headquarters 26th Infantry Division.” June 14, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“General Orders Number 30, Headquarters 26th Infantry Division.” November 1, 1944. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

History of a Combat Regiment 1639–1945 104th Infantry. Publisher unknown, c. 1945. World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Hospital Admission Card for 12211870. October 1944. U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/704106500/blank-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Wallace S. Wroten, Jr. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

“Monthly Roster of 13th Company of 20th Engineers (Forestry).” September 30, 1918. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-N3ZG-79SN-6

Morning Report for Company “E,” 104th Infantry Regiment. October 28, 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

“Provision of Enlisted Replacements.” Historical Section, Army Ground Forces, 1946.

“Sgt. W. S. Wroten, Jr.” Wilmington Morning News, June 3, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/article/149441707/

“Two Soldiers Burn To Death In Hannibal Fire.” The Maine Campus, February 17, 1944. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3691&context=mainecampus

“Wallace S. Wroten, Ex-Du Ponter, Dies.” Evening Journal, August 14, 1967. https://www.newspapers.com/article/149431106/

“Wallace Steuart Wroten Sr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/134800722/wallace_steuart_wroten

Wroten, Wallace S., Sr. Individual Military Service Record for Wallace Steuart Wroten, Jr. October 20, 1945. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/21526/rec/2

“W. S. Wroten Wins Posthumous Citation.” The Sunday Morning Star, December 10, 1944.” https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=VaBbNeojGYwC&dat=19441210&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

Last updated on January 7, 2026

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.