| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Machinist or apprentice at National Vulcanized Fibre Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32751491 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Company “B,” 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty (Presumed) | Campaigns/Battles |

| 653 (squad leader) | Naples-Foggia, Anzio, Rome-Arno, and North Apennines campaigns |

| Awards/Decorations | Entered the Service From |

| Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge | Wilmington, Delaware |

Author’s note: This piece includes some text from my previous article, 2nd Lieutenant William B. Weldon, Jr. (1916–1944), about an officer who served in the same battalion.

Early Life & Family

Edward Joseph Przylucki, Jr. was born in Wilmington, Delaware, on November 6, 1923. He was the son of Edward Joseph Przylucki, Sr. (also known as Edward Kasper Przylucke, c. 1893–1965) and Helen Przylucki (née Dziedzic, c. 1894–1933). His parents were Polish immigrants. Przylucki’s father had served in the U.S. Army during World War I before marrying his wife in Wilmington on July 15, 1920. Przylucki had an older sister, Mary Ann Przylucki (later Zabielski, 1922–1997).

At the time Przylucki was born, his family was living at 811 Taylor Street in Wilmington. His father had purchased the property on November 28, 1922, and his parents sold it on May 23, 1927. On June 3, 1927, his parents purchased another property at 425 South Jackson Street in Wilmington. Przylucki apparently lived there until he entered the service. At the time of the census in April 1930, Przylucki’s father was described as a cabinet maker at car shops (probably railroad car shops).

On January 26, 1933, when Przylucki was nine, his mother died of complications from thyroid disease at Wilmington General Hospital. Przylucki’s father remarried to Pauline Plystak (1904–2001). When the family was recorded on the next census in April 1940, the elder Przylucki was recorded as working as a “jointer” (probably joiner) in the railroad car repair industry.

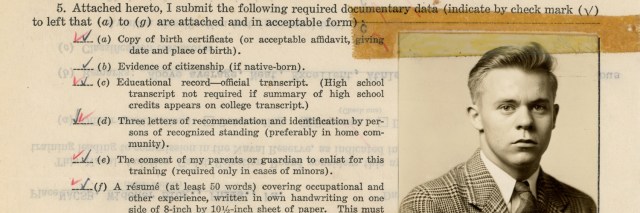

Przylucki graduated from St. Hedwig’s Parochial School and Brown Vocational High School. He was a Boy Scout and it appears he was also a Sea Scout. When Przylucki registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, he was working for the National Vulcanized Fibre Company at the corner of Maryland Avenue and Beech Street in Wilmington. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, five inches tall and weighing 130 lbs., with brown hair and hazel eyes. He was Catholic.

Przylucki’s enlistment data card described him as an apprentice with a high school education, while his father’s statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission described him as a machinist.

Training, Naples-Foggia, & Anzio Campaigns

After he was drafted, Przylucki joined the U.S. Army at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on February 17, 1943. His father’s statement indicates that Private Przylucki went on active duty at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on February 26, 1943, where he was stationed until March 1, 1943. Przylucki reported for basic training at Camp Wolters, Texas, on March 4, 1943. His father reported that Przylucki departed Camp Wolters on June 11, 1943, arriving three days later at the replacement depot at Camp Shenango, Pennsylvania. He remained there until July 22, 1943. A payroll record establishes that he went overseas on August 24, 1943. Przylucki’s father added that his son shipped out from the New York Port of Embarkation, arriving in North Africa on September 19, 1943, and Italy on September 30, 1943.

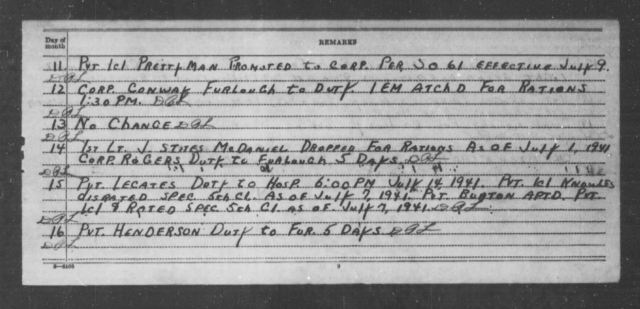

Private Przylucki was temporarily assigned to the 29th Replacement Battalion in Italy. On October 5, 1943, he joined Company “B,” 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division. The 168th Infantry was originally an Iowa National Guard unit that was federalized in 1941. The regiment had participated in the invasion of French North Africa and the Tunisian campaign before arriving in mainland Italy on September 21, 1943, about two weeks after the landings at Salerno. As Allied forces fought their way north, the regiment was involved in grueling combat along the Volturno and Rapido Rivers. According to his father, Private Przylucki first went into combat on October 10, 1943.

The Germans placed multiple defensive lines across the Italian peninsula to slow the Allied advance. The 34th Infantry Division was among the units that attacked the Bernhardt Line in December 1943 and early January 1944. The terrain and weather were as much of a challenge as the enemy. Supplies had to be brought in by mule and casualties had to be carried out by litter. On the night of January 16–17, 1944, the 168th Infantry went into reserve following the capture of Monte Trocchio after nearly two weeks of combat.

Penetrating the Bernhardt Line provided no decisive breakthrough, since the Germans had already prepared another defensive line: Across the valley from Monte Trocchio loomed Monte Cairo and Monte Cassino, strongpoints in the Gustav Line.

On January 25, 1944, Private Przylucki and six other men went on temporary duty at the Fifth Army Rest Camp for a few days. He was lucky enough to miss the beginning of the assault on the Gustav Line. During January 27–29, 1944, the 168th Infantry attacked the well-fortified Hills 56 and 213, fighting that cost the life of another Delawarean, Private Raymond W. Pierson (1922–1944).

The beginning of February 1944 was quiet for the 168th Infantry, but it was soon committed to attack Abbey Hill, as the Americans referred to the high ground where the Abbey of Monte Cassino was located. According to a regimental history, on February 8, 1944, the regiment began an attack on Hill 516, though Private Przylucki’s Company “B” remained in reserve. Companies “A” and “C” were so badly mauled in a pair of attacks “that it was necessary at the end of the day to combine then into one company. Just after dark Company ‘B’ moved up into the line.” The following night, “1st Battalion occupied positions formerly held by units of the 135th Infantry along the stone wall running north and south on the eastern slope and just below the crest of Hill 593.”

1st Battalion repulsed a pair of counterattacks on February 10, 1944. By then the battalion was severely understrength. Its three rifle companies had been reduced to an effective strength of just 154 men, less than a single full-strength rifle company was supposed to have. That night, Company “B” received some improvised reinforcements: men from an antitank platoon as well as some drivers and clerks. Not surprisingly, when 1st and 2nd Battalions attacked the following morning, February 11, 1944, they were quickly pinned down. The 168th Infantry switched over to the defensive. Abbey Hill would not fall to the Allies for another three months. 1st Battalion was pulled out of the line on the evening of February 13, 1944.

The following day, February 14, 1944, Przylucki was hospitalized at the 74th Station Hospital with cold weather injuries to his feet. Journal-Every Evening reported on April 18, 1944, that:

Corporal [sic] Przylucki has been hospitalized for several weeks in Italy. His feet were frozen while he was in the Cassino mountain combat and he writes home that he doesn’t want to see any more for the rest of his life.

The article added: “His letters are full of praise for the Red Cross and its work with the troops in Italy. He said he met movie star John Garfield in person while the latter was on tour of the hospitals.”

Private Przylucki rejoined his unit at the Anzio beachhead on May 18, 1944. A morning report listed his military occupational specialty at the time as 745, rifleman. The Anzio amphibious operation had begun in late January 1944 to flank the Gustav Line. Instead, German reinforcements had bottled up the invasion force without stripping their Gustav Line defenses, as Przylucki’s miserable experience in February had shown. By the time Przylucki arrived at Anzio, the beachhead had been static for over three months. That was able to change, however. In mid-May 1944, Allied forces finally broke through the Gustav Line and into the Liri Valley.

Rome-Arno Campaign

On May 23, 1944, the Allied forces at Anzio began a breakout, briefly threatening to encircle the German forces retreating from the Cassino sector. In the most controversial decision of his career, the commander of the U.S. Fifth Army, Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark (1896–1984), shifted the bulk of his forces northwest to capture Rome. As a result, the forces pushing out of Anzio faced yet another strong German defensive line, this one the Caesar Line running through the Alban Hills.

On May 28, 1944, the battalion began a series of unsuccessful assaults against Villa Crocetta, (located along the present day Via di Colle Crocette, southeast of Lanuvio). The Fifth Army History Part V: The Drive to Rome stated that:

On the right the 168th Infantry faced two particularly nasty strongpoints: Gennaro Hill and Villa Crocetta on the crest of Hill 209. As our troops approached either point, they had to cross open wheat fields on the neighboring hills, then make their way across the draws formed by the tributaries of Presciano Creek, and finally attack up steep slopes to their objectives. The German line was marked by a trench five to six feet deep which ran across Hill 209 and on past the southern slopes of Gennaro Hill. Based on this trench and its accompanying dugouts, machine guns were emplaced to command the draws, and mortars were located in close support. At Hill 209 the enemy also had wire nooses, trip wire, and single-strand barbed wire to break the impact of our charge.

1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment attacked Villa Crocetta twice on May 28, 1944. During the first attack, the battalion had been hit by friendly artillery. Among the men killed during the first two assaults was another Delawarean, 2nd Lieutenant William B. Weldon, Jr. (1916–1944), a member of Company “A.”

The following morning, 1st Battalion’s morale plummeted after a third failed attack. That time, the infantrymen had reached the objective, but once again American artillery fire was poorly coordinated with the attack. A bombardment intended to support the battalion’s advance instead forced them to retreat.

There was little respite for the weary infantrymen, who had been without adequate food or rest for almost a week. Lieutenant Colonel Wendell H. Langdon (1908–1984) ordered a fourth attack, scheduled for 1315 hours on May 29, 1944. Unlike during previous assaults, this time the infantrymen had the support of four M10 tank destroyers and three light tanks. All three rifle companies in 1st Battalion would take part.

When the attack began, only Private Przylucki’s Company “B” successfully attacked. According to regimental history, Companies “A” and “C” “were approaching the point of complete demoralization” and failed to advance. Even so, Company “B” “evidently took the enemy by surprise, for they withdrew from their entrenchments on the slope of the hill [203] without firing a shot.” Leaving six American soldiers to hold the position, the rest of Company “B” continued towards Villa Crocetta. They came under fire and were briefly pinned down, but with the support of the American armor, they managed to press on. However, the Germans returned to Hill 203, dislodged the six-man strongpoint, and opened fire on the rest of Company “B” with their machine guns.

Captain William W. Galt (1919–1944), the battalion operations officer, rallied the American troops as he manned a .50 machine gun mounted on an M10 tank destroyer commanded by 1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie (1914–1944) of Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. With the armored support, Company “B” routed the German infantrymen at Villa Crocetta. In keeping with their usual tactical doctrine of defense in depth, the German front line was lightly held, but they immediately counterattacked with infantry supported by four assault guns. The M10 was destroyed, killing four men including Galt and Jarvie, and Company “B” had no choice but to retreat. Captain Galt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, but the Caesar Line fighting had proved to be one of the most frustrating episodes in the history of the 34th Infantry Division. The Caesar Line was broken only when the neighboring 36th Infantry Division exploited a weak point.

Rome finally fell to the Allies on June 4, 1944, a victory soon overshadowed by the landings at Normandy. Despite the lion’s share of resources shifting to northwest Europe, fighting in Italy continued until mere days before the German capitulation. Allied strength was sufficient to tie down considerable German forces that otherwise would have been shifted to the Western or Eastern Fronts, but was not sufficient to overwhelm the successive German defensive lines. Similarly, after the invasion of the South of France, amphibious resources were shifted to the Pacific Theater, ruling out the possibility of another Anzio-style operation which may have shortened the fighting in Italy by months.

Although there was plenty of tough fighting, conditions during the summer of 1944 were considerably better for Przylucki and his comrades than any period since their arrival in Italy. If nothing else, maneuver warfare in the heat was more tolerable than attritional warfare in the cold and mud of the mountains. The Germans performed rear guard actions, demolished bridges, laid mines, and left boobytraps to slow the Allies while generally withdrawing to the north, where the terrain was to their advantage.

With the high casualties of World War II infantry combat, enlisted men sometimes advanced rapidly. On July 15, 1944, Private Przylucki was promoted three grades to sergeant. Presumably, he became an assistant squad leader at that time, though given the jump, he may have already been acting in that capacity. On July 19, 1944, the 34th Infantry Division captured Livorno (known as Leghorn in many English-language sources), though the Germans largely wrecked the major port’s facilities.

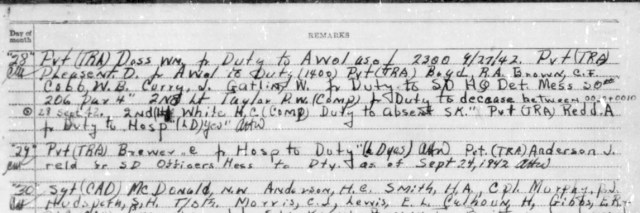

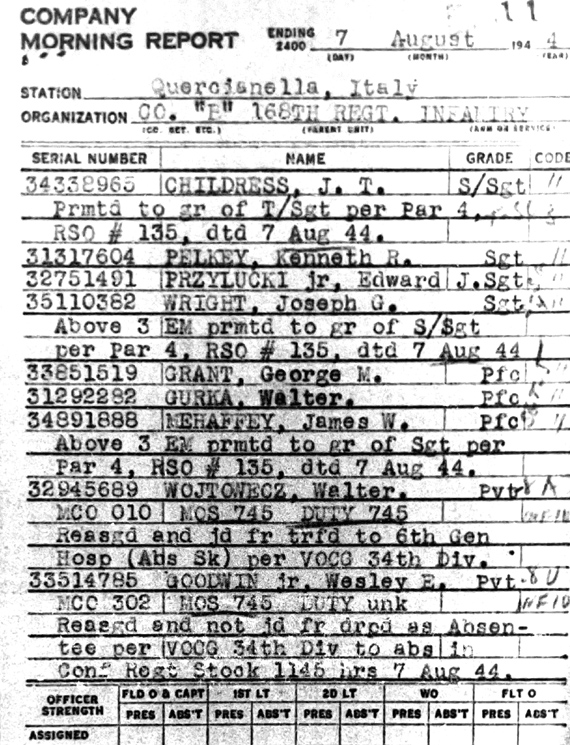

In late July 1944, the 34th Infantry Division was pulled out of the line for its first significant rest period since arriving in Italy. Sergeant Przylucki was among 10 men from his company who went on temporary duty at a Fifth Army Rest camp from August 4–9, 1944. On August 7, 1944, Przylucki was promoted to staff sergeant. From that point forward, he almost certainly served as a squad leader.

On August 24, 1944, the 168th Infantry moved to the area of Gambassi Terme. Early September saw generally small-scale actions as the Allies pursued the retreating Germans north of Florence.

North Apennines Campaign

By mid-September, the 34th Infantry Division was approaching the Gothic Line (also known as the Green Line), yet another tough German defensive line through the Apennine Mountains. South of the line, the Germans fought delaying actions. A typical engagement was the village of Collina, where Company “B” came under fire from a church occupied by an estimated squad-size enemy force:

Captain William H. Harris commanding Company “B” then led his company in a brilliantly executed attack on this strong point. Laying down heavy fire, the platoons advanced almost without interruption by fire and movement. 2nd Lieutenant Seymour Goldberg, and two enlisted men maintained almost constant fire on the enemy with Browing Automatic Rifles. […] The company, suffering no casualties in the action, drove the enemy up the ridge line to the northwest.

Pursuing the retreating enemy up the ridge, they got into a firefight with about 30 enemy infantrymen which continued until dark, when the company returned to Collina. The Americans had successfully captured the village, but the Germans had managed to delay a superior force from advancing on their main objective, Monte Frassino, which the Germans the Germans managed to fortify before the Americans reached it. Frassino would be taken by the 168th Infantry’s sister regiment, the 135th Infantry.

The 168th Infantry rested during September 12–15, 1944. From September 16–19, 1944, the regiment stood by in assembly areas, waiting for the right time to move on Monte Tronale. (The summit was designated Hill 1134, though the ridgeline of the mountain included high points designated Hills 1061, 1102, and 1105.)

1st Battalion returned to combat on September 21, 1944, moving north from Hill 725. It did not take long for them to encounter the sort of preparations that the Germans had been performing on the Gothic Line while their delaying actions were in progress further south:

The enemy had cut the timber on the ridge, so that it afforded little concealment. He had destroyed the usefulness of the trail on the western slopes of the ridge by mining it heavily and felling trees across it. He interdicted the draws on both sides of the ridge by continuous shell fire.

That afternoon, new orders came down for 1st Battalion to cut the road between Montepiano and Castiglione dei Pepoli, cutting off the avenue by which enemy forces to the south were expected to retreat. The attack was to begin at 2300 and continue through the night, with Company “B” leading the battalion.

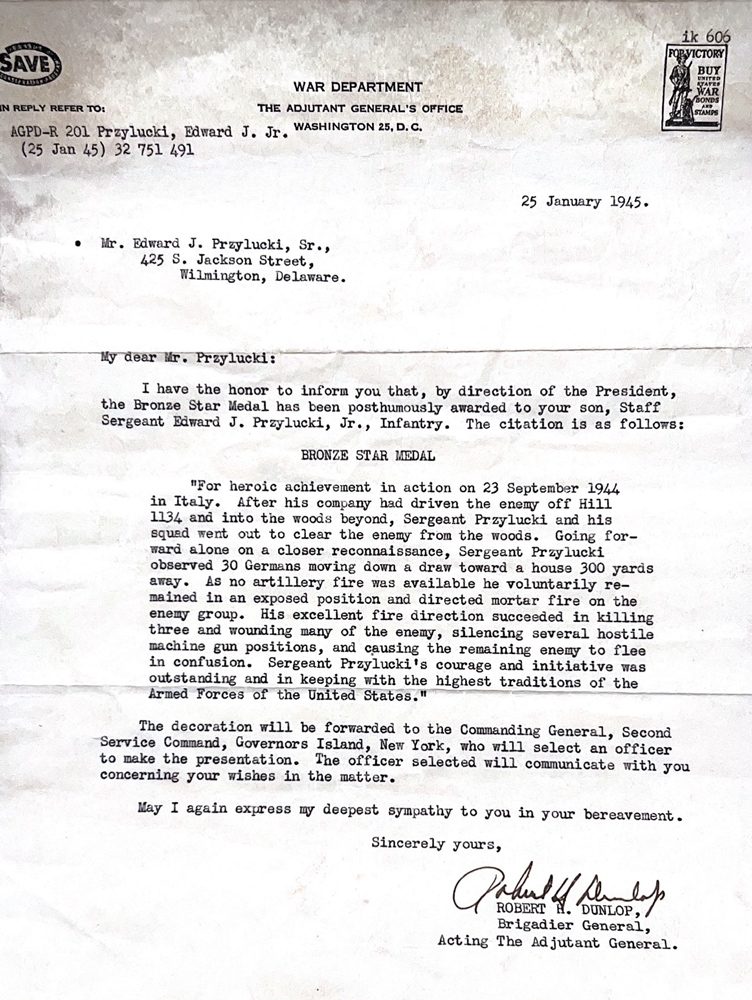

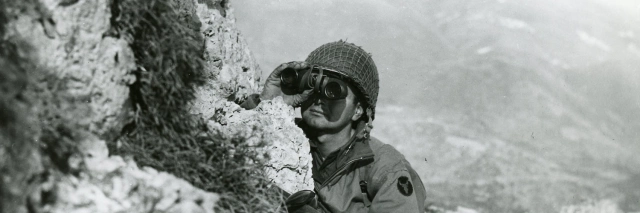

By 0645 on September 22, Company “B” reported it was on the nose (edge) of Hill 1134, and by 0710 it had taken the summit. The following day, September 23, 1944, Staff Sergeant Przylucki earned the Bronze Star Medal. The citation read in part:

After his company had driven the enemy off Hill 1134 and into the woods beyond, Sergeant Przylucki and his squad went out to clear the enemy from the woods. Going forward along on a closer reconnaissance, Sergeant Przylucki observed 30 Germans moving down a draw toward a house 300 yards away. As no artillery fire was available he voluntarily remained in an exposed position and directed mortar fire on the enemy group. His excellent fire direction succeeded in killing three and wounding many of the enemy, silencing several hostile machine gun positions, and causing the remaining enemy to flee in confusion.

There would be no rest yet for Staff Sergeant Przylucki and his comrades. That night, orders came down for 1st Battalion to “attack to the north astride the Montepiano–Castiglione road.” At 0830 the morning of September 24, 1944, 1st Battalion advanced north from Montepiano, with Company “B” in the lead.

When the advance elements reached a curve in the road approximately one thousand yards north of Montepiano, machine guns to the front and on the high ground on both flanks opened fire cutting off the 1st and 2nd Platoons of Company “B” from the rest of the company.

Enemy mortar and artillery fire joined the machine gun fire, adding to the misery of the pinned down platoons. Company “A” moved to assist and was similarly pinned down. Poor communications, partially due to damage to communications lines from enemy artillery, meant that 1st Battalion was essentially on its own. The reason for the ferocity of the enemy fire may not have been clear to Staff Sergeant Przylucki and his men, but the Germans were retreating and “the enemy was defending his axis of withdrawal in strength, inflicting eleven casualties on Company ‘B’ and five on Company ‘A’ in heavy fighting[.]” 1st Battalion was finally relieved on September 26, 1944, and went into reserve for the next three days as the 34th Infantry Division continued north.

On September 29, 1944, the Germans savaged a platoon from Company “C” that was reconnoitering the town of Montefredente, then after dark pursued them back to where the rest of the battalion was dug in at nearby Borgo. Company “B” and the rest of Company “C” beat off the counterattack. The following morning, Company “A” discovered that the enemy had already evacuated Montefredente. Company “B” went to work on a number of small enemy strongpoints, but was repulsed by one which had the support of a self-propelled gun. 1st Battalion pressed forward during the next two days with armor support. During October 1–2, 1944, they attacked a heavily fortified church and outbuildings on hill 789. There was little cover for the assaulting troops and by October 2, 1944, Companies attrition had reduced Companies “B” and “C” to an effective strength of two platoons rather than four. Some 205 rounds from American tanks plus bazooka fire from the infantry into the church finally convinced the Germans to pull out, although that was not discovered until the position was enveloped by an assault from 2nd and 3rd Battalions. The exhausted 1st Battalion briefly came out of the line. They were supposed to resume the offensive on October 5, 1944, but a devastating artillery barrage killed multiple 1st Battalion officers, necessitating a pause for an emergency reorganization. The battalion then went into defensive positions along the river Setta until the 168th Infantry went into reserve.

After several days of rest, Staff Sergeant Przylucki and his comrades returned to combat during a major Fifth Army offensive intended to break the Gothic Line and into the Po Valley before winter. Przylucki’s company commander was now 1st Lieutenant Ervin M. Frey (1919–1991), who had been a technical sergeant when he earned the Distinguished Service Cross at Villa Crocetta on May 29, 1944. He also received a rare battlefield commission afterward. H-Hour was set for 0500 hours on October 16, 1944. The attack began inauspiciously when the lead tank was knocked out and blocked the narrow road into Crocetta (not to be confused with Villa Crocetta). A second attack that afternoon bogged down, leading to a third attack that night. Company “B” with 2nd Platoon, Company “A” attached, made it about 200 yards before ending up in a frenzied close quarters firefight. The small enemy force withdrew and the Americans followed, only to come under fire from two sides. The regimental history stated that “1st Lt. Ervin M. Frey, faced with the possibility of a trap and the fact that ammunition was running short, decided to withdraw.”

The following morning, the 168th Infantry bypassed Crocetta and captured Tazzola. 1st Battalion captured some hills outside of town with the only resistance being “sporadic sniper fire[.]” On October 18, 1944, 1st Battalion’s fire assisted 3rd Battalion’s advances.

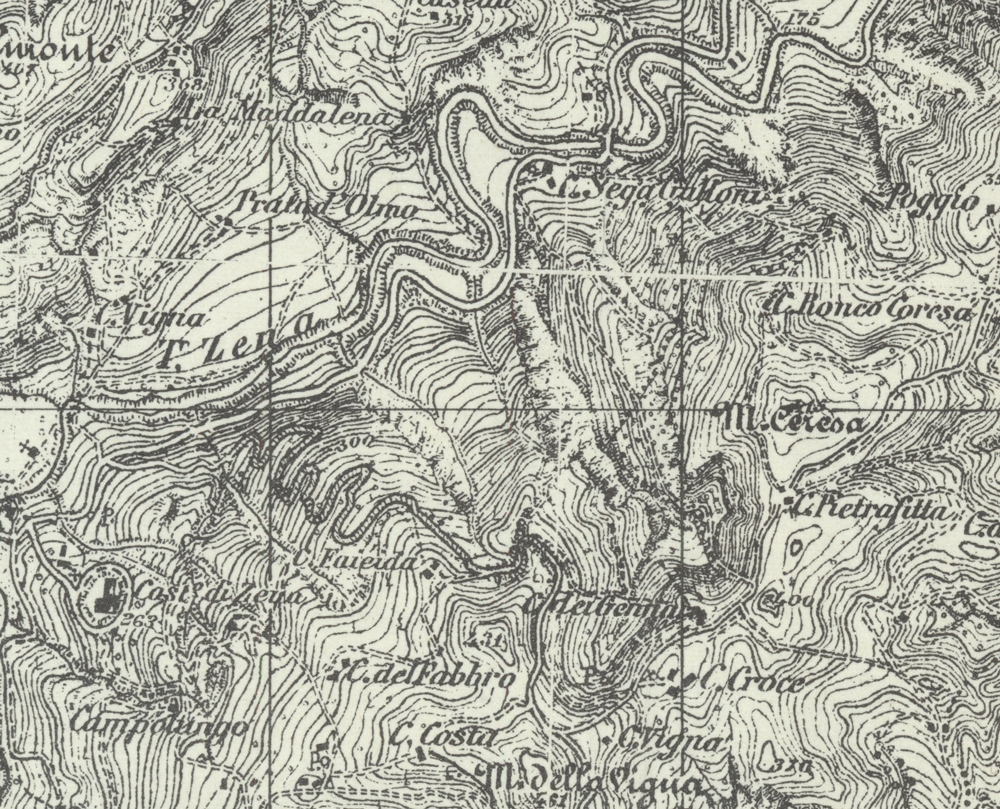

The next few days were quiet for 1st Battalion, but on October 21, 1944, Company “B” was attached to the now bogged-down 3rd Battalion for a mission intended to flank Monte Ceresa and take Collina Ronco Coresa. Companies “B” and “L” would lead the assault at 1600 hours. Although the regimental commander, Colonel Henry C. Hine, Jr. (1897–1989), had obtained significant firepower to assist the two companies, to preserve the element of surprise they were not used to soften up enemy positions. The men of both companies had to endure artillery, mortar, sniper, and machine gun fire while advancing to the line of departure. However, the assault went off without a hitch:

Promptly at 1600 hours all supporting fires opened up, including small arms, cal .50 machine guns, tanks, mortars, and artillery, and the troops launched their assault. The effect was quite electrifying as immediately almost all enemy firing was silenced, including his artillery. […]

After the first three hundred yards there was no cover and the men were forced to advance over a completely open slope. Firing from the hip as they advanced, the assault troops quickly over-ran the enemy’s forward positions. The enemy line broke, some escaping to the rear while others surrender in their fox holes. Company “L” continued its assault down the forward slopes and swung around toward C. Ronca Coresa. Here elements of both Company “B” and Company “L” surprised a company of enemy forming for a counter-attack, killing a number estimated between twenty and thirty. About forty prisoners were taken in the entire action. It is remarkable to note that during the assault, not a single casualty was suffered by our troops, so effective was the supporting fire and the surprise produced by the speed of the assault.

The regimental history noted that the successful assault “gave a decided boost to the morale” of 1st and 3rd Battalions. The following evening, Company “B” was detached from 3rd Battalion. On October 23, 1944, 1st Battalion was ordered to relieve “elements of the 133rd Infantry at Castello di Zena and occupying the ground up to the Zena River[.]”

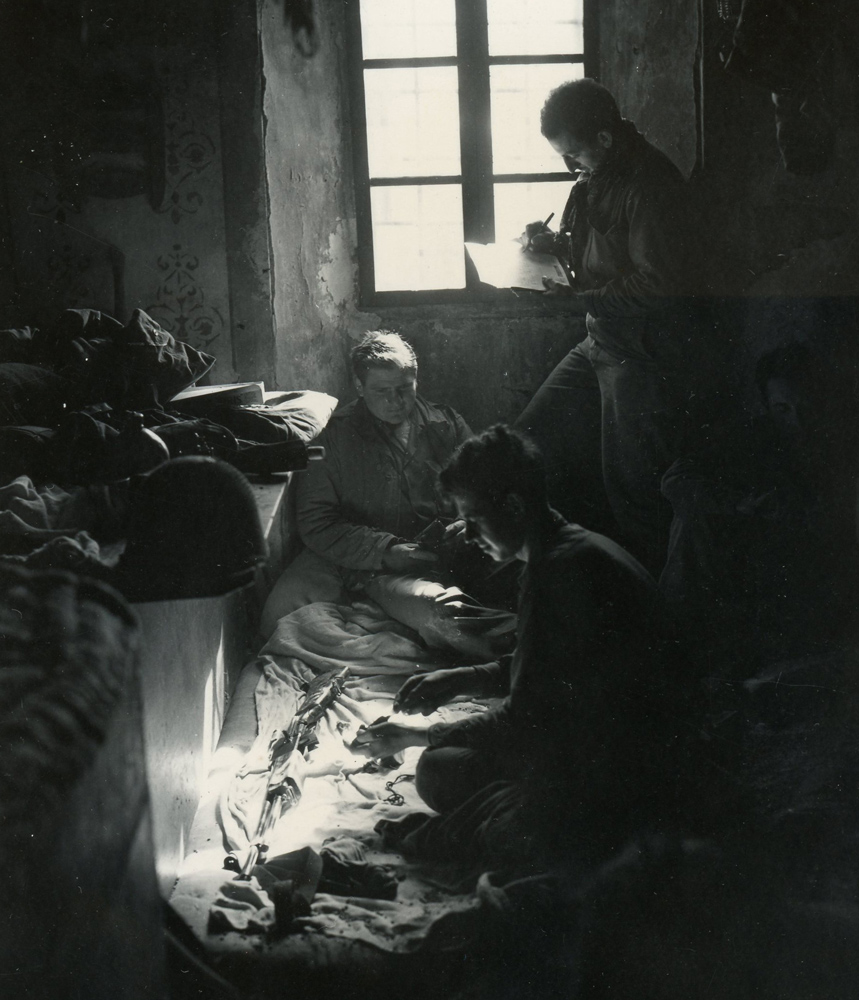

The pace of the offensive slowed, with the 168th Infantry taking up defensive positions and 1st Battalion mainly conducting patrols. There were several major benefits. The regimental history stated: “In this static situation, the companies were eating two hot meals a day, breakfast and supper[.]” In addition, “While not on out-post, the men lived in houses, where they could keep dry and heat their meals.” Two battalions would man the defensive line at any one time, with the third in reserve. Furthermore, “It was the aim of the regimental commander that the reserve battalion be as comfortable as possible.” A “Combat Shower Unit” and clothing exchange went into service on October 25, 1944, but was flooded out the same day. It would be three days before it returned to service. It appears Staff Sergeant Przylucki did not have the opportunity to avail himself of this simple pleasure before returning to combat.

Company “B” went back into the line on a pair of hills, that they referred to as Collina Sega Cra Moni and Collina Ronca Coresa, on October 25, 1944. The regimental report stated:

Company “B’s” position at Sega Cra Moni was subjected to harassing fire from 120mm mortars and self-propelled guns during the entire period that the company remained there. But the company maintained its positions and fired on the enemy as he showed himself. At C. Ronca Coresa, the men were also receiving heavy fire, although they had no contact with enemy infantry.

On October 27, 1944, Staff Sergeant Przylucki was lightly wounded in action, suffering a shell fragment wound to the right side of his neck. The wound was not serious enough to warrant hospitalization.

The Company “B” positions faced an enemy strongpoint along a stream, the Zena. The Germans occupied a number of houses, with additional enemy infantry emplaced in the nearby cliffs. At daybreak on October 29, 1944, Company “B” opened fire on the enemy positions, inadvertently stirring up a hornet’s nest. The regimental history stated that

the enemy’s reaction was instant and violent. 120mm mortars, self-propelled weapons, and tanks returned fire, principally on Sega Cra Moni. More than two hundred-and-fifty rounds landed in Company “B’s” area between dawn and 1430 hours. Seven casualties were incurred in one house, when several direct hits from a tank collapsed the walls.

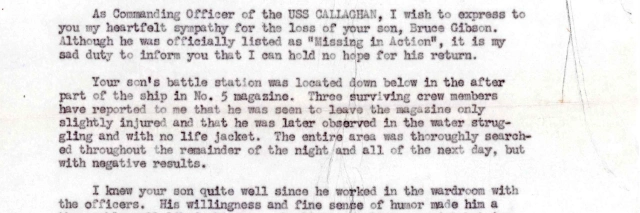

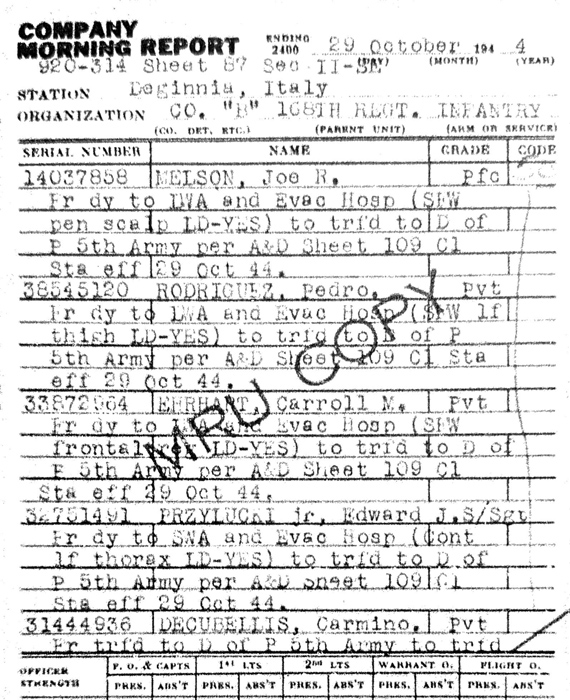

That day, Staff Sergeant Przylucki was severely wounded by an artillery shell on the left side of his thorax, fracturing several ribs and injuring his left lung. He was rushed to the 109th Medical Battalion’s clearing station and then transferred to the 94th Evacuation Hospital near Monghidoro, Italy. He died of his wounds the same day.

Przylucki was not wearing identification tags when he died. 1st Lieutenant Charles Taft Snowdon (1911–1992) identified his body, which was confirmed by his name on papers and a prayer book. He was also carrying a rosary and a notebook. These personal effects were eventually returned to his father the following year. However, on June 21, 1945, his father wrote the Army Effects Bureau, stating:

He had a wallet which contained quite a number of snapshots and pictures. Perhaps this was taken from him, but I have no way of knowing and would appreciate if you would go into this matter. It is not a pleasant thought, knowing that someone may have taken the wallet from him after he had given his life.

There is no indication that the wallet was ever found.

Staff Sergeant Przylucki was initially buried at a temporary military cemetery at Monte Beni, Pietramala, Italy, on November 2, 1944. The Wilmington Morning News reported his death on November 21, 1944. After the war, Przylucki’s father requested that his son’s be repatriated to the United States. His body returned home aboard the Lawrence Victory in the fall of 1948.

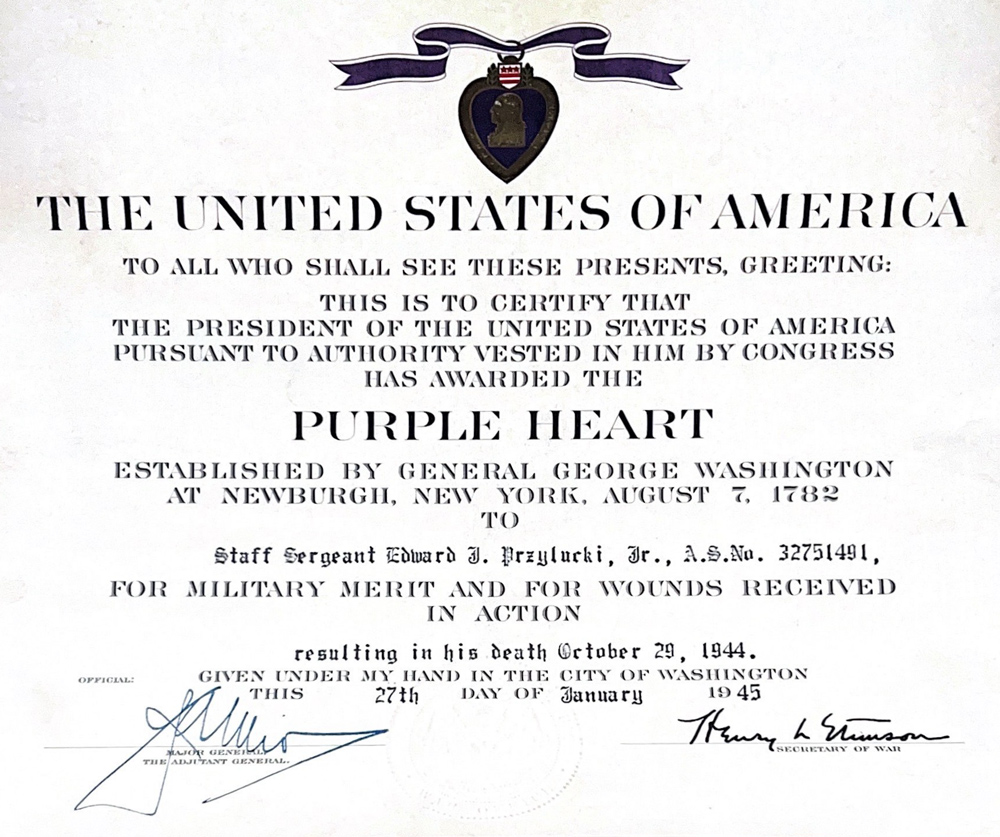

During his career, Staff Sergeant Przylucki earned the Bronze Star Medal, the Purple Heart, and the Combat Infantryman Badge. His Bronze Star was announced in January 1945 and presented to his father at Fort DuPont, Delaware, on August 9, 1945.

After requiem mass at St. Hedwig’s Roman Catholic Church on the morning of December 4, 1948, Staff Sergeant Przylucki was buried at Cathedral Cemetery in Wilmington, where his mother had been buried. His father, sister, and stepmother were also buried there after their deaths. His name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Notes

Squad Leader?

No M.O.S. codes were included in the last few morning report entries that mentioned Staff Sergeant Przylucki, though he was almost certainly a rifle squad leader. He was known to have been a rifleman earlier in his career, making it less likely that he had joined a mortar or light machine gun squad. Each full-strength rifle platoon had four staff sergeants: three squad leaders and a platoon guide. His Bronze Star citation, which referred to “Sergeant Przylucki and his squad”—which would tend to suggest he was a squad leader, not a platoon guide.

Hills

Hills were designated based on their heights on maps in meters. Maps of enemy territory were typically based on captured maps. Different scales of maps sometimes were developed decades apart and gave different topographical details. The so-called Hill 56 was a particularly egregious example. It was based on an apparently erroneous 1/25,000 map. The contemporary 1/50,000 map gave its height as 167 meters.

Lieutenant Snowdon

Lieutenant Snowdon, who identified Przylucki’s body, was a grandnephew of President Taft and a former Pittsburgh Steelers and Pirates player. He became a sportscaster after the war.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Przylucki family for contributing a photo and several documents, and to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research and Matt LeMasters for rosters and morning report entries that were vital for telling Staff Sergeant Przylucki’s story.

Bibliography

“4 Delaware Soldiers Given Awards, One Posthumously.” Journal-Every Evening, January 15, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/96224363/

“11 Who Gave Lives Will Be Honored.” Wilmington Morning News, August 8, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/article/134160690/

Application for Headstone or Marker for Edward J. Przylucki, Jr. December 6, 1948. Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8944-YZ7Q

Bronze Star Medal Citation for Staff Sergeant Edward J. Przylucki, Jr. January 25, 1945. Courtesy of the Przylucki family.

Certificate of Birth for Przylucki (girl). Undated, c. February 21, 1922. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DWBS-5D2

Certificate of Death for Helen Przylucki. January 26, 1933. Delaware Death Records. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DBB2-LM

Certificates Given Nineteen Sea Scouts.” Wilmington Morning News, April 15, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/article/134160234/

Certificate of Marriage for Edward Przylucki and Helen Dziedzic. July 15, 1920. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS75-7TNT

“City Soldier’s Feet Frozen In ‘Sunny Italy’ Campaign.” Journal-Every Evening, April 18, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/134159427/

“COL Henry Chester ‘Chet’ Hine Jr.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/126297334/henry-chester-hine

Delaware Land Records, 1677–1947. Record Group 2555-000-011, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_257016-00276, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61025/images/31303_257018-00155

“Deltonan Relives White House, War Years.” Evening News, December 3, 1984.

Draft Registration Card for Edward Joseph Przylucki. June 30, 1942. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_04_00007-00232

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531892_00325

“The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment from May 1, 1944 to May 31, 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/168th-infantry-regiment-history-may-1944.pdf

“The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment from May 1, 1944 to May 31, 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment (From October 1, 1944 to October 31, 1944).” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment (From September 1, 1944 to September 30, 1944).” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Edward J. Przylucki. Army Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1942–1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Morning reports for Company “B,” 168th Infantry Regiment. October 1943 – October 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Some reports courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller and Matt LeMasters.

“Narrative of the Action of the 168th Infantry Regiment January 1, 1944 to January 27, 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Pay Roll of Company ‘B’ 168th Infantry Regiment For month of October, 1943.” October 31, 1943. U.S. Army Muster Rolls and Rosters, November 1, 1912 – December 31, 1943. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

Przylucki, Edward J. Individual Military Service Record for Edward Joseph Przylucki. Undated, c. 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/20408/rec/1

“Requiem Mass Saturday For Sergeant Przylucki.” Journal-Every Evening, November 29, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/article/96224589/

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00552-00225

“Table of Organization and Equipment No. 7-17: Infantry Rifle Company.” War Department. February 26, 1944. Military Research Service website. http://www.militaryresearch.org/7-17%2026Feb44.pdf

U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/704875413/przylucki-edward-j-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954, https://www.fold3.com/record/704875412/przylucki-edward-j-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32751491&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3297418

“Wounded Soldier Dies; 7 Others Hurt in Action.” Wilmington Morning News, November 21, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/article/96224363/

Last updated on August 4, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.