| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland? | Truck driver |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Naval Reserve | 8127397 |

| Theater | Vessel |

| Pacific | U.S.S. Callaghan (DD-792) |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Mariana Islands, Western Caroline Islands, Leyte, Luzon, fleet raids against Honshu, Iwo Jima, Okinawa |

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my previous piece, Steward’s Mate 1st Class John Bryant (1925–1945), another black sailor killed off Okinawa.

Early Life & Family

John Bruce Gibson was probably born on January 27, 1918, in either Ridgley, Maryland, or Atlantic City, New Jersey. He was the son of John H. Gibson (1882–1963) and Clara Gibson (née Ross, c. 1882–1954). Various records over the years described his father as a chauffeur, municipal dog catcher, and finally owner of a fish market. His mother was a seamstress. Gibson was recorded on the census on April 21, 1930, living with his parents at 1203 Columbia Avenue in Pleasantville, New Jersey.

As of 1932, Gibson was attending the Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth in Bordentown, New Jersey. The Bordentown School was an unusual example of a state coed vocational boarding school for black children. A March 28, 1932, article in the Atlantic City Press mentioned: “John B. Gibson Jr., a student at Manuel [sic] Training School, Bordentown, is passing Easter with his mother, Mrs. Clara Gibson, 203 Columbia av., Pleasantville.” Gibson told the Navy that he had completed two years of high school.

As a young man, Gibson ran into trouble with the law. He was arrested twice for larceny by the Pleasantville Police Department in 1932, but the charges were dropped. On April 24, 1933, the New Jersey State Police charged Gibson with two counts of larceny of automobile. On June 19, 1933, he was sentenced to two years of probation for those vehicle thefts. He was arrested again by Pleasantville Police for vehicle theft on August 30, 1933. Whether because he was convicted of the crime or it was considered a violation of his probation, Gibson wrote that he “was placed in detention” until January 26, 1935.

Soon after his release, Gibson joined the Civilian Conservation Corps but was again accused of vehicle theft, this time in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The Atlantic City Press reported that on March 16, 1935, “Gibson was apprehended on the CCC camp grounds at Tuckahoe” by New Jersey State Police “and was taken to the county jail to await the arrival of Atlantic City detectives. A teletype message was responsible for his arrest.”

This time, Gibson was convicted of grand larceny and sentenced to five to seven years in prison. He was released on February 26, 1940. Gibson later stated: “I tried to join the Navy at Brunswick, New Jersey back in 1940 at the Navy Recruiting Station, but they told me my record was not clean enough.”

Gibson later told the Navy:

On April 17, 1941, I was arrested by the Police Department of Atlantic City, New Jersey, as being undesirable and was sentenced to six months in the County Jail. Being that I was born and raised in the community this sentence was dropped and I was released after serving about one month of my sentence.

Gibson later told the Navy in a November 5, 1943, statement: “From June 18, 1941 until August 17, 1943, I had held several positions in civil life, I worked as a driver for a packing concern and worked in a defense job in a Graphite Mine, Chester Springs, Pa.”

When Gibson registered for the draft on February 4, 1943, he was unemployed and living at 908 Poplar Street in Wilmington, Delaware. Curiously, he registered as Bruce Gibson with no middle initial rather than as John Bruce Gibson. Even odder, the registrar recorded Gibson’s date of birth as January 27, 1925, at Ridgley, Maryland, seven years after his real birthdate.

Exactly what happened is unclear. Did Gibson tell the registrar that he was 25 years old and she instead recorded his birth year as 1925? Was he trying to increase the chance that he would be drafted by describing himself as younger than he was? Did he claim to be 18 years old to avoid trouble over the fact that he evidently failed to register as required by law on R-Day, October 16, 1940? (See the Notes section for more details.)

The registrar described Gibson as standing six feet, three inches tall and weighing 195 lbs., with black hair and brown eyes, while the Navy recorded his physical characteristics as six feet, one inch tall and 174 lbs. when he was inducted later that year.

Gibson’s mother told the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission that her son was a laborer before entering the service. He stated he was unemployed at the time he entered the service on August 17, 1943, but indicated his last occupation was two years working as truck driver for a slaughterhouse. Journal-Every Evening reported that Gibson “was employed at the New Market on King Street.”

Navy Career

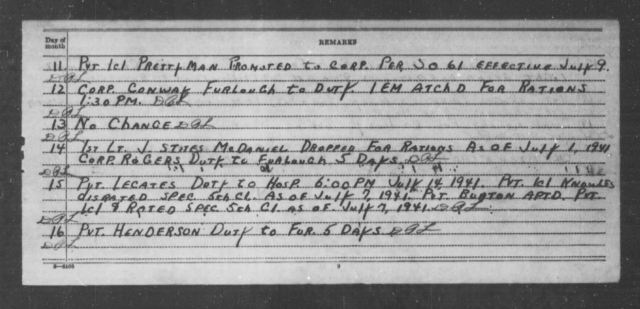

After he was drafted, Gibson requested naval service, making him what the U.S. Navy termed a “selective volunteer.” Whatever his reasons for giving his name as Bruce Gibson instead of John Bruce Gibson and his year of birth as 1925 instead of 1918, Gibson stuck to the information he had given the draft board earlier during his induction into the Navy. He was also less than forthcoming about his criminal record.

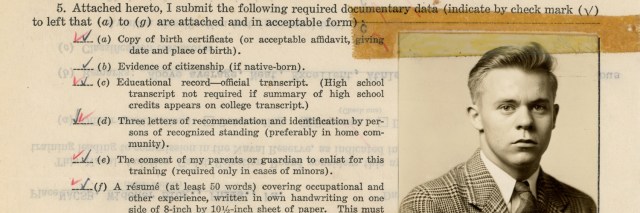

Bryant joined the U.S. Naval Reserve in Camden, New Jersey, on August 17, 1943, and was appointed a steward’s mate 3rd class. The U.S. armed forces were segregated during the World War II era. Black sailors like Bryant typically had limited career paths open to them. With few exceptions, they could serve only as cooks and stewards for officers. There was almost no opportunity to become a petty officer.

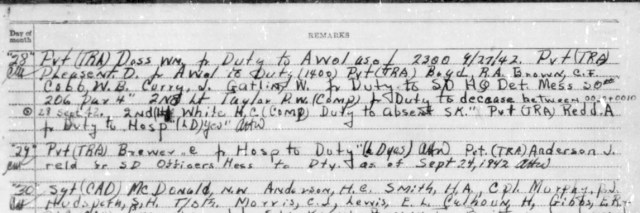

Gibson went on active duty on August 24, 1943. That day, he began five weeks of boot camp at the U.S. Naval Training Station, Bainbridge, Maryland. Upon graduation, on September 28, 1943, he was promoted to steward’s mate 2nd class. Some records are incomplete due to the loss of his original service record booklet when his ship sank. Customarily, a sailor received a week of recruit leave after boot camp. On October 12, 1943, Gibson was dispatched to the Receiving Ship, San Francisco, California, “for duty under instruction in DESTROYER TRAINING PROGRAM.”

Steward’s Mate 2nd Class Gibson’s past soon endangered his future in the Navy. On October 17, 1943, he reported for duty at the Receiving Ship, San Francisco, California. About two weeks later, on October 30, 1943, he was “held as a prisoner-at-large”—that is, confined to the station, not in a cell—“on charges of fraudulent enlistment[.]” The Bureau of Naval Personnel had begun an investigation into the discrepancy of Gibson’s date of birth and had discovered his criminal history (or soon would).

In a statement dated November 5, 1943, Gibson tacitly admitted that he had been deceptive about his criminal record during induction:

I enlisted in the U.S. Navy at the U.S. Naval Recruiting Station, Camden, New Jersey, on August 17, 1943, at which time the recruiting office asked me if I had previously had a police record. I replied that I had and stated that I had been placed on one year’s parole from Wilmington, Delaware. At which time the recruiting office stated that this charge was not sufficient enough to keep me out of the Navy.

There is no evidence that Gibson was ever convicted of a crime in Delaware. However, he disclosed his arrests and convictions during 1932–1941, which the Navy was able to confirm with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Gibson added that “I had kept my civil record clean after the last charge as being undesirable as I found that obeying the law was more beneficial to me.”

Confronted about the discrepancy in his date of birth, Gibson told the Navy in a statement dated February 8, 1944:

I was born on January 27, 1918. It must have been some mistake made in my record because I explained to the draft board about my record and they said they had a certain number of men to take into the armed services and that if they didn’t want me they would send me back from the training station.

On February 8, 1944, Gibson’s commanding officer, Robert R. Williams, Jr., told the Bureau of Naval Personnel that “Based upon performance of duty and service to date, the Commanding officer recommends that the subject named man be retained in the Naval service.” On February 17, 1944, a letter in the name of Chief of Naval Personnel Admiral Randall Jacobs (1885–1967) directed the commanding officer of the Receiving Ship to “Retain and warn regarding other than complete and truthful statements in matters of official nature.”

In San Francisco, Gibson befriended a woman named Leona E. Clarke (later Debrois, 1925–1981). The two corresponded until his death.

Within a few months, Gibson shipped out for Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, where he joined the crew of the Fletcher-class destroyer U.S.S. Callaghan (DD-792) on May 9, 1944. During the summer of 1944, the destroyer supported operations to capture the Mariana Islands. In early September 1944, Callaghan escorted carriers during operations in the Western Caroline Islands. On September 23, 1944, Callaghan’s captain, Commander Francis Joseph Johnson (1907–1995), demoted Gibson to steward’s mate 3rd class on the basis that he “Proved not qualified for rating of StM2c.”

On October 12, 1944, Gibson was subject to a captain’s mast for falling asleep while on watch. Commander Johnson directed that he be punished with five days in “solitary confinement on bread and water.” Since his ship did not have a brig and was kept busy supporting operations for the liberation of the Philippine Islands, the punishment could not immediately be carried out. During the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Callaghan screened the carrier force. On October 24, 1944, her crew rescued a downed flier, Aviation Radioman 3rd Class E. E. Brown from the U.S.S. Lexington (CV-16) but did not arrive in time to save his pilot, Commander Richard McGowan (1912–1944). The following day, Callaghan was involved in a surface action in which a force of American cruisers and destroyers finished off the already damaged Japanese carrier Chiyoda.

Commander Charles Marriner Bertholf (1912–1991) assumed command of U.S.S. Callaghan at Ulithi, Caroline Islands, on October 31, 1944. The destroyer spent much of November operating off the Philippines, except a brief break at Ulithi in the middle of the month, and rescued a downed pilot on November 24. She returned to Ulithi on December 2, 1944. Two days later, Gibson was transferred to the carrier U.S.S. Essex (CV-9) for his long-delayed punishment to be carried out. Gibson transferred back to U.S.S. Callaghan on December 9, 1944.

Callaghan sortied again from Ulithi on December 11, 1944, escorting carriers for airstrikes against Luzon, Philippine Islands. The rest of the month was uneventful except for rescuing an overboard sailor from the U.S.S. Ticonderoga (CV-14).

Commander Bertholf promoted Gibson back to steward’s mate 2nd class on January 1, 1945.

In January 1945, Callaghan escorted the fleet during attacks on Luzon, Indochina, and Formosa (Taiwan). The following month, she accompanied carriers during raids on Honshu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. On February 18, 1945, she sank a small Japanese picket craft and rescued eight survivors. She returned to Ulithi on March 5, 1945. The next few weeks were quiet except for reprovisioning and some patrol work. It was the last break Steward’s Mate 2nd Class Gibson and the rest of the crew would have for the next four months.

Okinawa & Final Engagement

On March 21, 1945, Callaghan departed Ulithi. The same day, her crew rescued an overboard man from U.S.S. Sangamon (CVE-26). She arrived off Okinawa on March 25, 1945. The following day, the destroyer began shore bombardment in preparation for the upcoming amphibious operation.

Shortly before sunrise the following morning, around 0605 hours on March 27, 1945, Callaghan had a close call when she came under attack from three enemy aircraft, identified as Aichi D3A Type 99 (“Val”) dive bombers. The first managed to drop its bomb, which missed, and was obliterated by a direct 5” hit after circling back around. The second plane, apparently intending a suicide attack, was set afire by the destroyer’s light antiaircraft guns and “overshot the ship, crashing in the water 100 yards off the port quarter[.]” A similar process played out with the third plane, which was set afire during its dive:

The plane passed over the ship between the stacks. One of the wheels of the landing gear caught the port radio antenna and carried it away. The plane crashed into the water about 50 feet off the port beam, exploding as it hit the water, throwing hundreds of pieces of metal and sea water all over topside.

That was merely the first notable encounter of the day. At 0736 hours, a lookout spotted a periscope at point blank range. Commander Bertholf later recalled in an interview:

I ran out to the bridge and naturally looked a thousand or two thousand yards away and the lookout said, “No, Captain, he’s alongside.” And sure enough, there about 35 yards off the beam, was this periscope. All I can remember thinking of is that this can’t be happening to me all in one hour. We dropped all our port depth charges and as the ship was only making about eight knots, I thought I had sunk the Callaghan rather than the submarine, and I’m sure that the man in the after steering room was of the same opinion. However, the midget submarine came up and rolled over and sank, and that was the start of our four months and four days at Okinawa.

On the first day of the landings on Okinawa, April 1, 1945, Callaghan bombarded enemy targets ashore and defended the fleet from attacking aircraft. That night, shortly after midnight on April 2, an unidentified aircraft strafed the destroyer, killing one man, before the fleet’s firepower brought the plane down.

During the months that followed, Callaghan was in action continuously. She performed various missions including the bombardment of shore targets, illuminating the battlefield at night, screening larger warships, convoy escort, antisubmarine patrol, and radar picket duty. Commander Bertholf later recalled:

Our schedule was roughly four days and four nights of firing without letup followed by the fifth day of replenishment of ammunition at Kerama Retto which was supposed to be the day of rest of the crew. However, they, of course spent the whole day loading ammunition. During the fifth night they sometimes would let us anchor under the smoke but you usually spent half the night at General Quarters anyhow.

On May 25, 1945, Callaghan rescued two injured Japanese aviators from a plane shot down while attacking the ship. One of the prisoners died of his wounds before he could be transferred. On June 3, 1945, the destroyer rescued a downed American pilot, an Ensign Billingsworth from the U.S.S. White Plains (CVE-66).

On June 12, 1945, Gibson was convicted of neglect of duty at a deck court-martial and sentenced to the loss of $18 of his pay for two months.

Okinawa was secure by the end of June 1945. The end of the land battle, however, did not end the threat from enemy aircraft, which had launched both conventional and suicide attacks throughout the campaign. Thanks to these violent air attacks, U.S. Navy fatalities during the Battle of Okinawa (4,907) were higher than those of the U.S. Army (4,412) and Marine Corps (2,779).

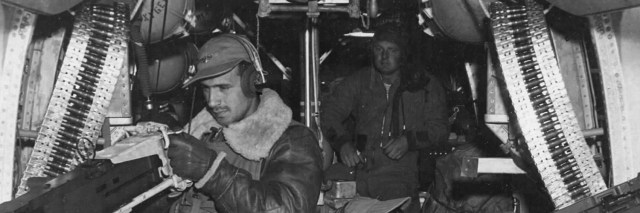

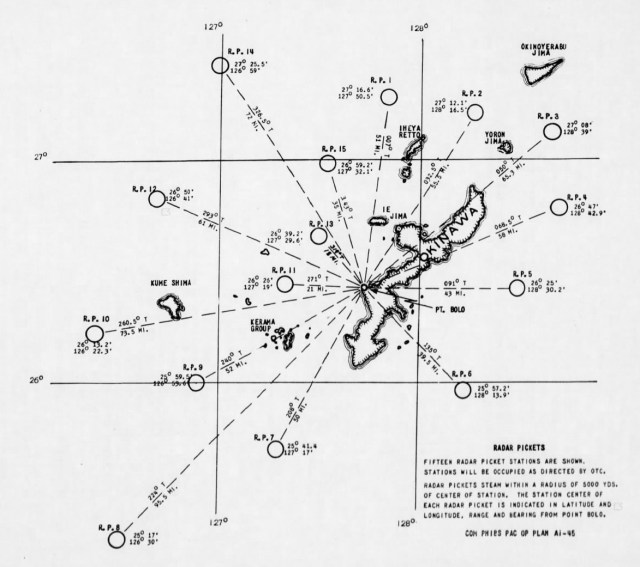

Radar picket duty off Okinawa was one of the most hazardous assignments U.S. Navy destroyers faced during World War II. The pickets provided early warning of inbound Japanese aircraft. Although the Japanese Special Attack Unit pilots, better known to the Americans as kamikazes, were supposed to prioritize more valuable targets than destroyers, in practice many simply attacked the first American ships they came across.

Around 0600 hours on July 28, 1945, Callaghan departed from Hagushi Anchorage and sailed west for her last night of picket duty. She was nearly excused from the mission entirely. Orders were about to come down dispatching her for an overhaul back in the continental United States. Given that it was just eight days before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the destroyer surely would not have returned to the Pacific Theater before the surrender of Japan. Bertholf later recalled:

The screen commander told the squadron commander that inasmuch as we might leave on the 29th for the West Coast he wouldn’t send us out. But Captain A. E. Jarrell, ComDesRon 55 [Commander, Destroyer Squadron 55], said he preferred to go in case the orders were changed. So we proceeded to sea and that evening did receive confirmation of our orders.

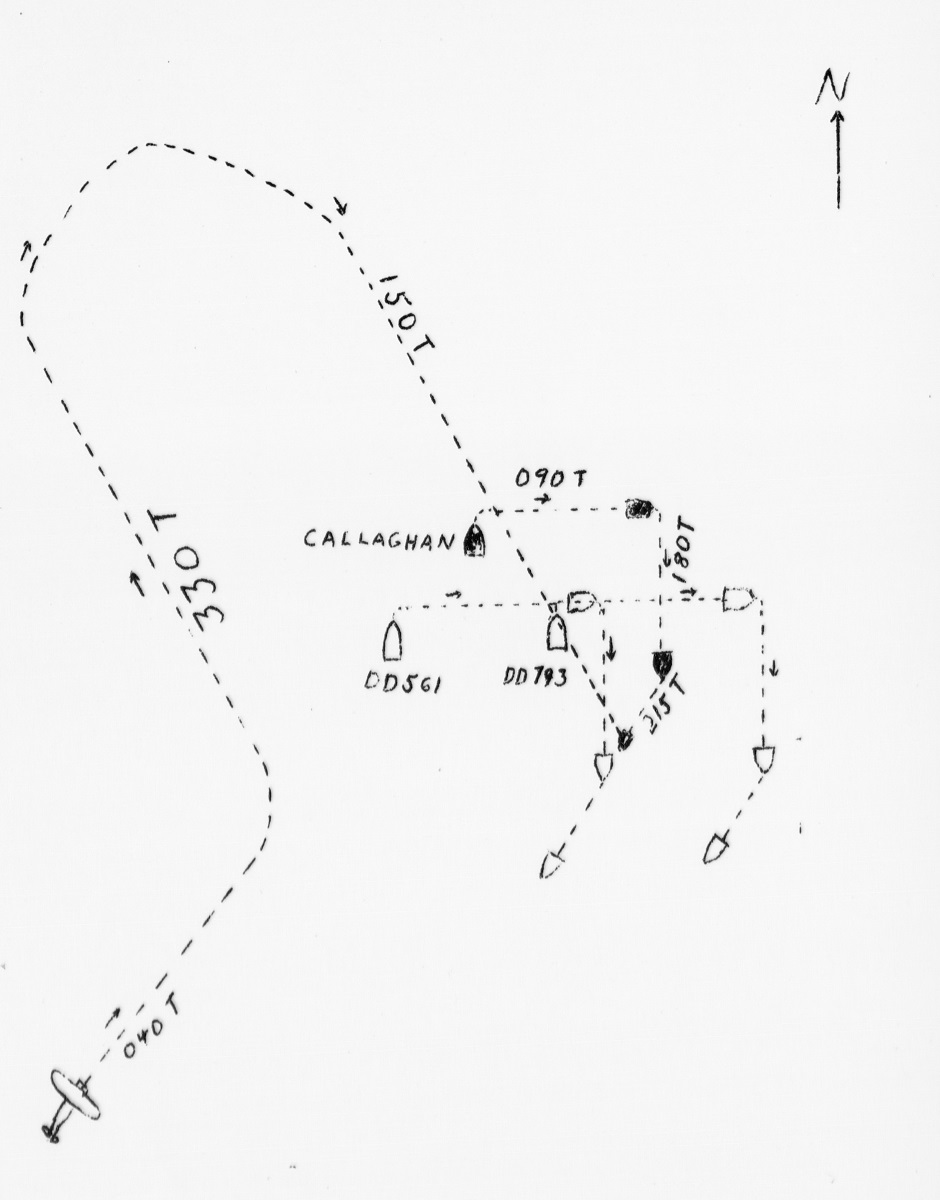

Shortly after midnight on July 29, 1945, Callaghan was at Radar Picket Station 9 Able, 60 nautical miles southwest of Point Bolo, Okinawa, along with the destroyers Cassin Young (DD-793) and Pritchett (DD-561), and several landing craft, support: LCS-125, LCS-129, and LCS-130. The ships were sailing due north at 12 knots.

Callaghan was due to be relieved by another ship at 0130. Luck was not with her, however. Although their radar gave them an early warning of enemy aircraft, the ships were silhouetted against a bright moon. At 0028 hours, “PRITCHETT reported a bogie bearing 230°T, distance 13 miles on TBS [talk between ships radio]. At 0030, CALLAGHAN picked up bogie bearing 200°T, distance 9 miles.”

A contact just nine nautical miles out was alarmingly close, just six minutes’ flying time from the small flotilla. Callaghan’s commanding officer explained:

It is believed that the plane was not picked up at a greater range because it was fabric coated. SC Radar had been picking planes up at a range of 60 to 70 miles the previous day, but did not pick up the suicide plane until it was in to 9 miles range.

He continued: “At 0031, General Quarters was sounded and at 0034, opened fire with 5″ battery on bogey closing on a course of 040°T, speed 90 knots, low on the water.”

Although career opportunities for black sailors were sharply limited, in combat, every member of the crew had a battle station. Gibson was assigned to the No. 5 Magazine. If he wasn’t already awake, at General Quarters, Gibson would have leapt from his bunk and rushed to his battle station.

Under ordinary circumstances, the enemy plane—a single-engine biplane with fixed landing gear, identified in secondary sources as a Yokosuka K5Y (“Willow”)—would have been a laughable threat to a modern destroyer. As a human-controlled guided missile filled with fuel and armed with a bomb, however, the kamikaze proved deadly.

It was not immediately clear that the attacker was a kamikaze. Commander Bertholf wrote that during Callaghan’s service at Okinawa, “the great majority of night enemy air attacks had been torpedo and bombing – relatively few suicides. […] Until just before the hit, the Commanding Officer still felt that everything pointed to a torpedo attack.” The Destroyer Squadron 55 commander, Captain Albert E. Jarrell (1901–1977), concurred with that assessment in his own report.

At 0035, the American ships turned east and accelerated to 25 knots. The enemy plane flew close to the formation, apparently to identify them, then briefly flew away to set up for its attack run. Callaghan may have become a target because some of the handling room crews inadvertently sent some powder that was not flashless to the 5-inch gun mounts. These shells also had a “blinding effect” on the gunners of the lighter 20 mm and 40 mm cannons.

Callaghan’s gunners were experienced at fighting against enemy aircraft and the destroyer had already been credited with downing a dozen Japanese planes during her career. In this final engagement, Callaghan fired 61 conventional antiaircraft 5-inch shells and 200 5-inch V.T. shells without apparent damage to the attacker. V.T. shells, equipped with proximity fuzes, were a secret Allied innovation that had proved highly effective against Japanese aircraft. Thanks to the proximity fuze, the shells did not have to score a direct hit. The shell’s electronics sent out signals which were reflected back by the target and would cause the shell to detonate at a lethal distance. Callaghan’s skipper later speculated that, just as it had decreased the plane’s radar signature, “the material from which the plane was constructed reduced the effectiveness of VT ammunition.”

Despite several minutes of evasive maneuvers and intense antiaircraft fire, the kamikaze crashed into Callaghan at 0041 hours. The “Suicide plane hit the ship on the main deck in the vicinity of the starboard forward corner of 5″ mount No. 3 Upper Handling Room with a bomb (about 250 pounds) going into the After Engine Room and exploding.”

The crew desperately fought the fires, hampered by damage to the fire main. The flames impinged on the volatile No. 3 Upper Handling Room. The loss of the fire main prevented magazine personnel from flooding the No. 3 and No. 4 Magazines. “The crew of the No. 3 Upper Handling Room were seen to be throwing powder cans over the side” but even this heroic action failed to prevent a massive explosion four minutes after the plane crash, killing the entire No. 3 Upper Handling Room crew. Callaghan immediately began listing to starboard and settling by the stern.

After the magazine explosion, Commander Bertholf ordered “All hands, except Salvage Party, prepare to abandon ship.” The destroyer slowed to a stop and at 0050, Bertholf ordered his crew, except for the salvage party, into the water. LCS-125 assisted with firefighting and removing the wounded, even as other enemy aircraft entered the area. Despite the efforts of both crews, the flooding and explosions could not be controlled and the last of the crew abandoned ship at 0144. Callaghan slipped beneath the waves at around 0235 hours, the last ship lost to kamikazes.

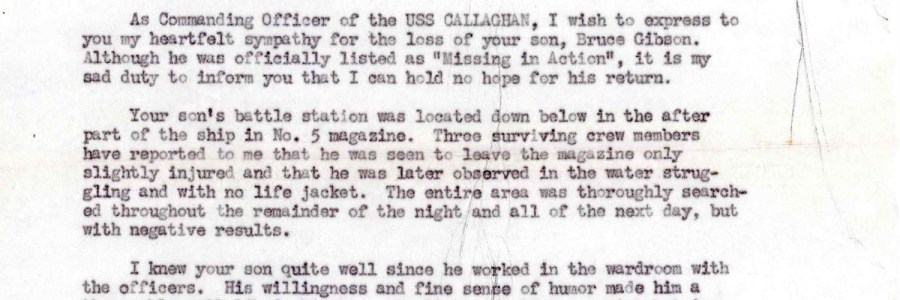

Commander Bertholf’s letter to Clara Gibson dated September 25, 1945, was more personal than the boilerplate condolence letters many families of World War II fallen received, stating in part:

As Commanding Officer of the USS CALLAGHAN, I wish to express to you my heartfelt sympathy for the loss of your son, Bruce Gibson. Although he was officially listed as “Missing in Action”, it is my sad duty to inform you that I can hold no hope for his return.

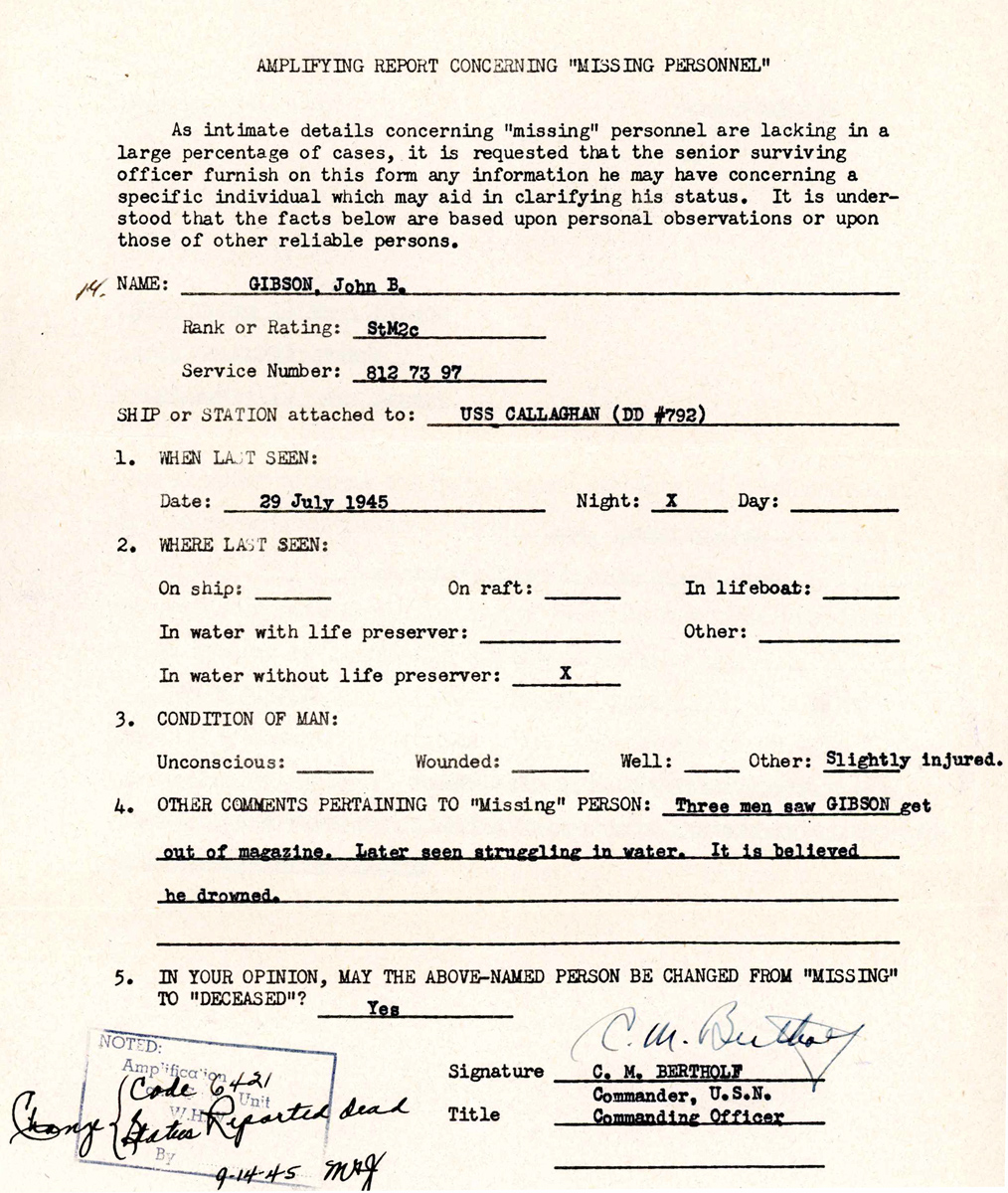

Your son’s battle station was located down below in the after part of the ship in the No. 5 magazine. Three surviving crew members have reported to me that he was seen to leave the magazine only slightly injured and that he was later observed in the water struggling and with no life jacket. The entire area was thoroughly searched throughout the remainder of the night and all of the next day, but with negative results.

I knew your son quite well since he worked in the wardroom with the officers. His willingness and fine sense of humor made him a thoroughly well liked shipmate. On 12 August 1945, a quiet but impressive memorial service was held for all the young men who lost their lives in this action.

In his report, Commander Bertholf recommended that destroyers should be equipped with more kapok life jackets, which were not even available for all topside crew. He noted that “Many pneumatic life belts were punctured by shrapnel and were of no use.”

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, Callaghan’s casualties were recorded as 47 men missing and 73 men wounded.

Upon his commanding officer’s recommendation, Gibson’s status was changed from missing in action to killed in action on September 12, 1945. Gibson was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

Bruce Gibson Veterans of Foreign Wars Post No. 6594 in Pleasantville, now closed, was named in his honor. His mother’s obituary stated that she was the “founder and president of the Bruce Gibson Post Auxiliary 6594.” His name is also honored at the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii, and at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Birth & Early Life

Gibson’s records and statements are extremely inconsistent about his birthplace and early life. The 1930 census stated that his parents were born in Maryland but that Gibson himself was born in New Jersey. Similarly, he told the Navy that the “undesirable” charges were dropped because “I was born and raised in the community” of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Indeed, his mother told the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission that her son was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey. On the other hand, Gibson told the draft registrar that he was born in Ridgely, in Caroline County on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. His Navy shipping articles gave the same place of birth.

Gibson’s name did not appear in the Atlantic County, Atlantic City, or Caroline County birth indexes, though it is unclear how complete they are. Another puzzling detail is the fact that Gibson’s parents were recorded living in Pleasantville on the census taken January 24, 1920, but no children were listed. Was it a mistake by the census enumerator? Was Gibson living with other relatives at that time? Was the 1918 date of birth also wrong? Was he not his parents’ biological child but rather adopted by them after January 1920?

Mother’s Middle Name

Clara Gibson gave her maiden name as Ross in her statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission. Some records list Clara Gibson’s middle initial as O. Gibson gave his mother’s name as Clara LaRosa Gibson when he entered the Navy.

1940 Draft Card?

Assuming the January 27, 1918, birthdate was accurate, Gibson was 22 years old and was required by law to register for the draft on the first registration day (R-Day), October 16, 1940. His 1943 registration would seem to suggest that he did not do so for over two years.

Curiously, a man giving his name as John Bruce Gibson registered for the draft in Port Monmouth, New Jersey, on October 16, 1940. He gave his residence as Wilson Avenue in Port Monmouth, New Jersey. His date of birth was listed as January 27, 1916, a remarkable coincidence. His place of birth was listed as Peoakie, Florida (possibly referring to Pahokee, Florida). The registrar described his physical characteristics as Negro, six feet 2½ inches tall and weighing 192 lbs., very similar to Bruce Gibson’s 1943 card (six feet, three inches tall and 195 lbs.). There is no sign of a John Bruce Gibson born in Florida in 1916 who lived in New Jersey in 1940 on any census or similar indexed records from the era.

Of course, given the general dearth of historical records from the period, especially for black Americans, the absence of documentation does not prove that Gibson was the same man who registered for the draft in Port Monmouth. It is unclear what his motivation would have been for registering for the draft twice. Although some aspects of their signatures are similar, there are also notable differences.

Date of Sinking

Oddly enough, several secondary sources (including U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, Navsource, and Wikipedia) state that Callaghan was sunk on July 28, 1945, rather than July 29, 1945. However, the latter date is attested to in Gibson’s personnel file, in American Battle Monuments Commission records, muster rolls, and in contemporary reports and war diaries from the ships, destroyer squadron, and destroyer division involved.

Bibliography

Bertholf, Charles M. “ACTION REPORT – Report of Capture of OKINAWA GUNTO, Phases One and Two.” June 22, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/101713792

Bertholf, Charles M. “Narrative by: Commander C. M. Bertholf USS CALLAGHAN, DD 792.” Interview on September 29, 1945. World War II Oral Histories, Interviews and Statements. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/278475552

Bertholf, Charles M. “Report of A.A. Action by Surface Ship, U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792), on 29 July 1945.” August 8, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/101771496?objectPage=17

Bertholf, Charles M. “U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792) Action Report of 29 July 1945.” August 8, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/101771496

Bertholf, Charles M. “U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792) War Diary for Month of January, 1945.” February 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139851688

Bertholf, Charles M. “U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792) War Diary for Month of July, 1945.” April 1, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/83531576

Bertholf, Charles M. “U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792) War Diary for Month of March, 1945.” August 11, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139967251

Bertholf, Charles M. “U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792), War Diary for Month of November, 1944.” December 1, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139767392

Bertholf, Charles M. “War Diary for Month of December, 1944.” January 6, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139805339

Birth Indexes, Geographical 1915 – 1919 Atlantic County – Bergen County (part) (Part 1). New Jersey State Archives, Trenton, New Jersey. https://archive.org/details/New_Jersey_Geographic_Birth_Index_-_reel_38_-_1915-1919/page/n41/mode/1up

“Brief News Notes.” Atlantic City Press, March 28, 1932. https://www.newspapers.com/article/135920450/

“City Seaman Declared Officially Dead by Navy.” Journal-Every Evening, May 9, 1946. https://www.newspapers.com/article/135916231/

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4660847_00254

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4313309-00701

Gibson, Clara. Individual Military Service Record for John Bruce Gibson. January 30, 1947. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18813/rec/1

“Held In Auto Theft.” Atlantic City Press, March 17, 1935. https://www.newspapers.com/article/135915808/

Index to Births occurring 1910 – 1919 F – G. Maryland State Department of Health Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1939. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/stagserm/sm1/sm27/000000/000004/pdf/msa_sm27_000004.pdf

Jarrell, Albert E. “Anti-aircraft Action Report for Action of 29 July, 1945 – Loss of U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792).” August 7, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/83522605

Johnson, Francis J. “Action Report U.S.S. CALLAGHAN (DD792) of 25 October 1944.” October 29, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/77570181

Johnson, Francis J. “War Diary for month of October 1944.” October 31, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/78679060

Johnson, Francis J. “War Diary for month of September 1944.” September 30, 1944. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/287139743/war-diary-91-3044-page-1-us-world-war-ii-war-diaries-1941-1945

Official Military Personnel File for Bruce Gibson. Official Military Personnel Files, 1885–1998. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Services Set Monday For Mrs. Clara Gibson.” Atlantic City Press, December 4, 1954. https://www.newspapers.com/article/135979102/

Silverman, Lowell. “Steward’s Mate 1st Class John Bryant (1925–1945). Delaware’s World War II Fallen website, August 16, 2023. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2023/08/16/stewards-mate-1st-class-john-bryant/

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02303-00418, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00319-00349

Streator, George. “School In Jersey Aids Negro Youths.” The New York Times, November 21, 1948. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1948/11/21/96604690.html?pageNumber=67

World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005217835_01949

World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_13_00004-00671

WWII Draft Registration Cards for New Jersey October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44025_02_00039-02684

“Youth Held By Police On Auto Theft Charge.” Atlantic City Press, September 1, 1933. https://www.newspapers.com/article/135920707/

Last updated on December 22, 2023

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.