| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| North Carolina, South Carolina, Delaware | Carpenter |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army Air Forces | 12012609 |

| Theater | Unit |

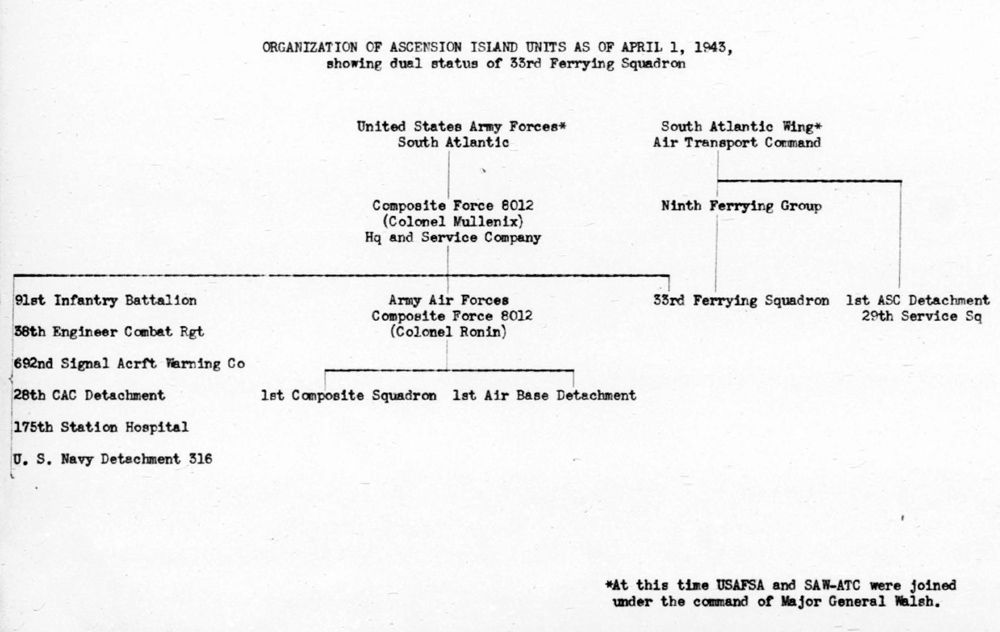

| European–African–Middle Eastern Area | 1st Composite Squadron, Composite Force 8012 |

Early Life & Family

Charles Henry Horton was born on May 8, 1916, in Iredell County, North Carolina. He was the son of Joseph Ernest Horton (1891–1973) and Mary Tolbert Horton (also known as Mary Estelle Horton or Estelle Tolbert Horton, 1891–1982). Horton was recorded on the census in January 1920, living with his parents and younger sister on the family farm on Lewis Ferry Road in Shiloh Township in Iredell County. On the next census, recorded in April1930, he was still living in Shiloh Township with his parents and five younger sisters.

Census records and Horton’s enlistment data card described Horton as a high school graduate. Census records indicate that Horton was a resident of York, South Carolina, as of April 1, 1935. That was also his residence when he married Pearl Mae Childers (later Pearl Mae Childers Parker, 1915–2004) on June 6, 1936, in Concord, North Carolina. The couple had one daughter, Emily Cleo Horton (later Emily Parker Robinson, who briefly served in the U.S. Army, 1939–1978). The couple subsequently divorced.

Horton was recorded on the census in April 1940 as a lodger living with two dozen other workers (including his father and uncle) at 218 South Ashe Street in Greensboro, North Carolina. He was described as working as a carpenter for a construction company.

Horton registered for the draft in Wilmington, Delaware, on October 16, 1940. Although he was working for Delaware Builders in nearby Wilmington Manor at the time, he apparently considered it temporary since he gave his address as Rural Free Delivery No. 4 in Reidsville, North Carolina. The registrar described him as standing five feet, 10½ inches tall and weighing 158 lbs., with brown hair and eyes.

Horton remarried on April 19, 1941, to Lula Smith in York, South Carolina. The couple had one son. Horton’s enlistment data card described him as a carpenter. His military paperwork described him as standing five feet, 8¼ inches tall and weighing 139 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. He was Protestant.

Military Career

Horton volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Forces one week after the attack on Pearl Harbor, enlisting in Wilmington, Delaware, on December 16, 1941. Lula Horton was pregnant when he enlisted. It is unclear if Horton ever had the opportunity to meet his son, who was born in North Carolina early the next year.

According to documents in his Individual Deceased Personnel File (I.D.P.F.), Private Horton was briefly stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey, before moving to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, for basic training. He was briefly stationed at Will Rogers Field, Oklahoma, beginning in January 1942. He moved to Savannah, Georgia, on an unknown date, and to Key Field, Mississippi in March 1942.

Private Horton was one of 55 men in the first contingent of to join the Air Base Detachment (later known as the 1st Air Base Detachment) at Key Field on March 21, 1942. He may have shipped out from the Charleston Port of Embarkation around July 26, 1942, arriving at Ascension Island on August 14, 1942. Regardless, by April 7, 1943, Horton had been promoted to corporal and was a member of the 1st Air Base Detachment on Ascension Island. He was promoted to sergeant on July 1, 1943.

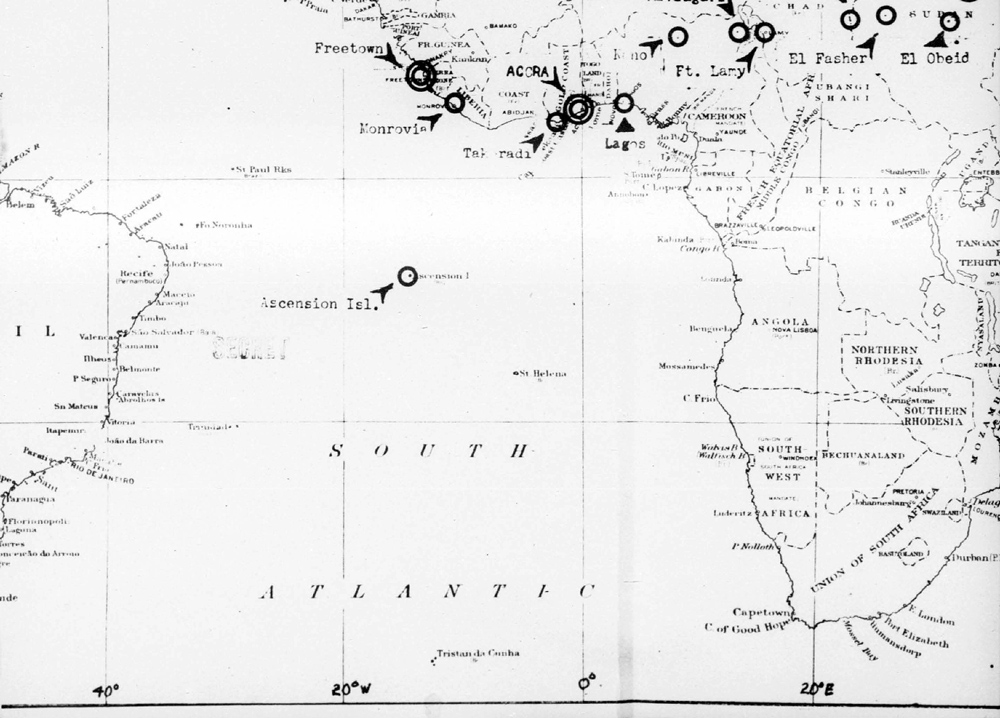

Ascension Island, a British possession, is an isolated and sparsely inhabited volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. During World War II, the island’s location midway between South America and Africa was of great strategic importance for the Allies. On December 25, 1941, shortly after the U.S. entry into World War II, Air Corps Ferrying Command (known as Air Transport Command from June 1942) began the process of surveying the island to build an airfield. Codenamed Lawyer, Ascension would be a useful air link across the South Atlantic for planes moving to Europe, Africa, and the Far East.

After reaching an agreement with the British in 1942, American engineers built what was soon known as Wideawake Field, after a nickname for the local sooty terns. The first runway was completed on July 10, 1942. U.S. forces on Ascension were organized as Composite Force 8012, including small U.S. Army Infantry, Coast Artillery, Corps of Engineers, Signal Corps, Quartermaster Corps, and Medical Department units, as well as a U.S. Navy detachment. The first Air Transport Command plane landed at Wideawake Field on July 10, 1942. The following month, the 1st Air Base Detachment and 1st Composite Squadron arrived. These two U.S.A.A.F. units were placed under the Composite Force 8012 umbrella, though Air Transport Command South Atlantic Wing units at Ascension had a separate chain of command.

Over 1,238 aircraft transited Ascension Island in 1942, followed by 6,935 planes in 1943 and 10,083 planes in 1944. Especially in the early days, conditions were spartan, with men housed in tents or crowded barracks. Collection of rainwater on Green Mountain and desalination provided enough water for drinking but rarely enough for laundry or hygiene beyond shaving and sponge baths. Initially there was little fresh food aside from locally caught fish, sea turtles, and tern eggs. Davis wrote that “Swimming, fishing trips, movies and baseball games were the principal types of diversion.” The baseball diamond was facetiously named Ebbets Field, after the Brookyln Dodgers’ stadium. Engineers also built several movie theaters.

On January 26, 1944, Sergeant Horton transferred to the 1st Composite Squadron, also stationed on Ascension Island. The 1st Composite Squadron had been activated on March 12, 1942. The squadron was unusual in that it was equipped with both Bell P-39 Aircobra fighters, as well as North American B-25 Mitchell and Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers. The squadron’s mission, along with Navy aircraft stationed there, was to defend Ascension Island and protect shipping passing within 500 miles of the island.

The 1st Composite Squadron had been involved in an infamous event that may have cost the lives of hundreds or thousands of Allied mariners. On September 12, 1942, the German submarine U-156 sank the British ship Laconia, carrying Italian prisoners of war as well as Allied civilians. To his credit, Admiral Karl Dönitz (1891–1980) ordered other submarines to the area to begin a rescue mission. The Germans radioed their humanitarian intentions in the clear and draped Red Cross flags across the decks of their submarines. Four days later, however, a B-24 assigned to the squadron attacked U-156. The 1st Composite Squadron pressed the attack the following day. The attacks killed some of the Laconia’s survivors but did not sink any Germany submarines. More importantly, Admiral Dönitz responded with the Laconia Order, banning U-boats from rescuing or assisting survivors of sunken Allied vessels except when taking prisoners for intelligence purposes.

Horton was promoted to staff sergeant on February 1, 1944. His assignment in the 1st Composite Squadron is unclear, though he was not one of the squadron’s air crew. George A. Davis mentioned Sergeant Horton in his 1945 history of Wideawake Field:

Because of a scarcity of lumber on the island, the men experimented with local materials for construction. Staff Sergeant Charles H. Horton of the Composite Squadron [sic] was probably the pioneer in these experiments; at any rate, he worked untiringly until he made a successful concrete cinder block. It was made from a mixture of cement and a generous amount of local lava and finer volcanic material, and a coarse sand probably formed from shell and coral. The cost for these blocks was less than that of the lumber it displaced and they were more easily obtainable. The strength of the concrete was sufficient for its use and the block buildings were cooler than wooden ones. The ATC mess hall and clubs were built from these blocks.

Davis mentioned in his report that the Atlantic Ocean off Ascension “was quite dangerous because of the undertow and huge rollers which rise without warning.”

Tragedy on Ascension Island

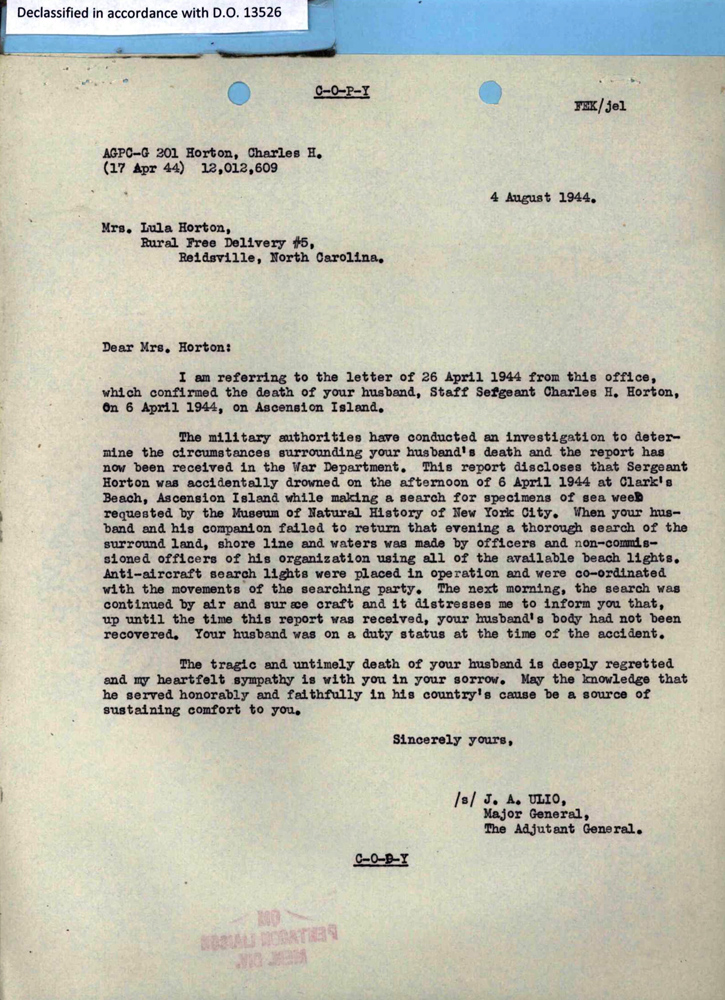

Initially, the American base on Ascension was considered a closely guarded secret. Until December 1943, censorship forbade the personnel stationed there from informing their families that they were on Ascension. One soldier recalled that regulations even prevented them from writing that they were on an island or mentioning that they were near the ocean! At the end of 1943, authorities publicly announced the existence of an American base on Ascension Island for the first time. As with the Laconia incident, this decision would have unintended consequences, as documented in the findings of a board of officers convened to investigate a pair of disappearances.

On March 17, 1944, the director of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, Albert E. Parr (1900–1991), wrote a letter to the War Department “requesting specimens of seaweeds which were thought by the museum to grow abundantly in rocky pools and immediately below the low water mark on the shores of Ascension Island.”

Although the request was at first glance a remarkably esoteric one to make of the War Department during the middle of the most destructive war in human history, Davis explained in his report that the request had potential significance not just for science but also the war effort: “The Museum proposed to check early reports that the Ascension seaweed bears an important relation to that existing in the Sargasso Sea, possibly gathering valuable information on Atlantic currents and winds.”

Parr’s innocuous request was forwarded down the chain of command with surprising speed, eventually ending up assigned to the Composite Force 8012’s force engineer, Major Langley T. Gatling, Jr. (1915–1944) by the afternoon of April 5, 1944, when per the board’s findings, he “requested a gallon pail with a tight lid from Cpl. Harwood at the Engineer Dump, and remarked that he was going to get seaweed for the War Department.”

The following day, Major Gatling, having recruited Staff Sergeant Horton to assist him, set off to get the sample. The board wrote:

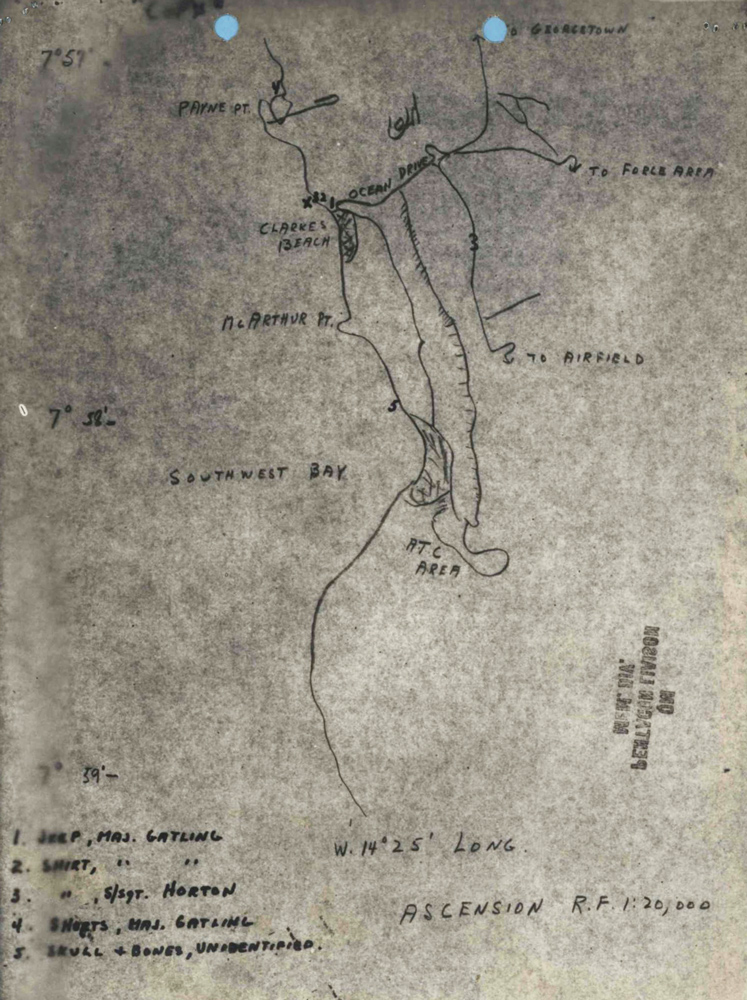

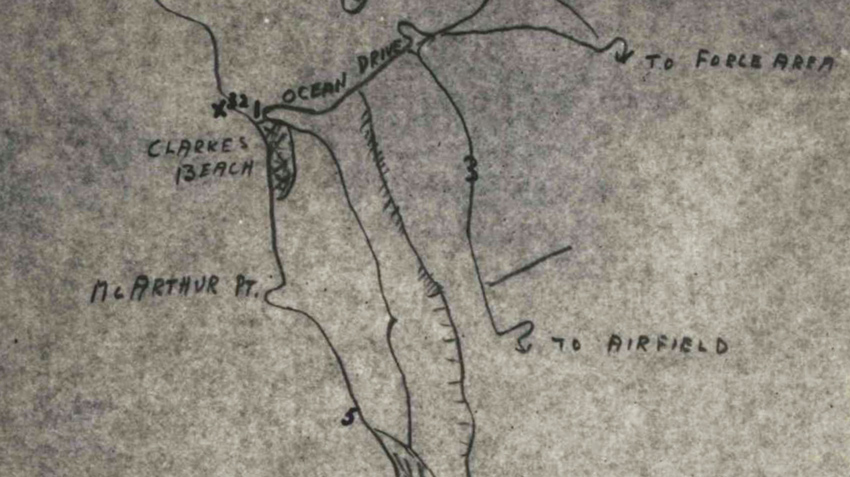

On Thursday, April 6, 1944, about 1530 hours, Major Gatling picked up S/Sgt. Horton in a “Jeep” at the new laundry site. At about 1615 hours, they drove past the laundry site on Ascension Island Route #3 going southwest towards the junction of Ascension Island Route #3 and Ocean Drive.

Approximately the latter time Major Gatling and S/Sgt. Horton were seen driving down Ocean Drive towards Clark’s Beach.

The two men were never seen again. At around 1845 hours, a soldier performing guard duty at Clark’s Beach (also known as Clarkes Beach) found an unattended jeep. “Shortly after 1900 hours two shirts were found near the water’s edge” but there was no sign of the two men.

That evening, soldiers from the island’s garrison searched the shore with the aid of searchlights. The waters offshore were too hazardous to search that night due heavy waves: “The rollers were of such magnitude, height and force that they were breaking ten or fifteen feet over some of the rocks, in the area which were estimated to be about twenty feet high.” The following morning, boats and a Consolidated OA-10 Catalina flying boat searched the area without success.

On April 8, searchers found some of Major Gatling’s clothing. That same day, some human remains were recovered. Remarkably, these turned out to be those of Sergeant Stewart S. Milligan (1917–1944), a third soldier who disappeared on Ascension Island on the same day as Gatling and Horton. Milligan was last seen at Southwest Bay, about one mile from Clark Beach, and presumably was a victim of the same rough seas that claimed Gatling and Horton’s lives.

In the absence of any bodies, the board of officers could only speculate about what happened, suggesting:

While looking for the requested seaweed, either Major Gatling or S/Sgt Horton fell in the ocean, or was washed into the ocean by the heavy rollers: the other one [then] attempted to rescue him and likewise fell or was washed into the ocean; the waves or rollers then battered their bodies against the jagged rocks which severely injured them to the extent that they could not help themselves, or rendered them unconscious.

They concluded “That Staff Sergeant Charles H. Horton, sometime between the hours of 1615 and 1845, on April 6, 1944, met death by drowning as the facts and circumstances surrounding this case lead to no other logical conclusion.”

Staff Sergeant Horton’s name is honored on the Tablets of the Missing at the North Africa American Cemetery in Tunisia. However, his name was omitted from Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

First Marriage

It appears that Horton and his first wife were separated by April 1, 1940. The census described him as married, but her as either single or divorced.

Bibliography

“1st Composite Squadron Personnel Changes – February 1944.” Reel A0145. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“1st Composite Squadron Personnel Changes – January 1944.” Reel A0145. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Air Base Detachment.” Reel A0685. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Davis, George A. “History of Wideawake Field, Ascension Island, 1159th AAF Base Unit, South Atlantic Division, Air Transport Command, December, 1941 – December, 1944.” September 1945. Reel A0145. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4608295_00581

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4383838_00288

“Historical Record Army Air Force Composite Force 8012.” Headquarters Ascension, South Atlantic, January – February 1944. Reel A0145. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

“Historical Review of First Composite Squadron Army Air Force Composite Force 8012 A.P.O. 877.” 1943. Reel A0685. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Individual Deceased Personnel File for Charles H. Horton. Individual Deceased Personnel Files, 1939–1953. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Morning Reports for 1st Air Base Detachment. July 1943. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/partners/st-louis/rg-064/85713825-wwii/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0413/85713825_1940-01-thru-1943-07_Roll-0413-11.pdf

North Carolina Birth Indexes. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, North Carolina. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8783/images/NCVR_B_C054_68001-0652

North Carolina Marriage Records, 1741–2011. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, North Carolina. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60548/images/42091_327469-00987

“Pearl Mae Childers Parker.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/134498648/pearl-mae-parker

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02920-00435, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-03846-00579, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-02881-00683

“Summary of Anti-Submarine Attacks in Ascension Area.” Undated, c. November 5, 1943. Reel A0685. Courtesy of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=12012609&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=483785

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/32892_620303988_0091-03547

Last updated on December 6, 2024

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.