| Home State | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware | Worker for the Bond Manufacturing Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32751640 |

| Theater | Unit |

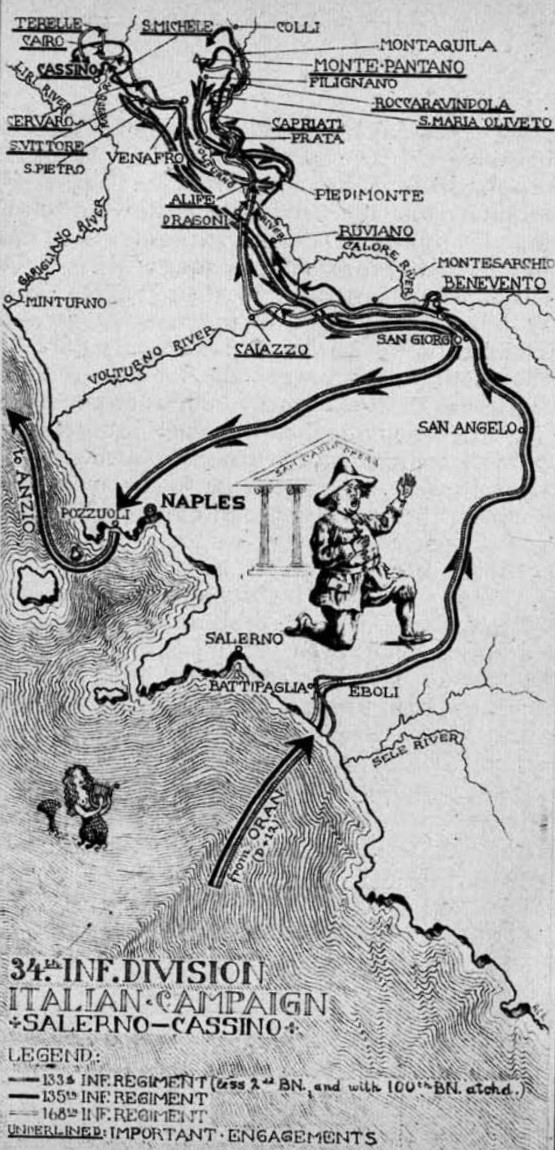

| Mediterranean | Company “C,” 133rd Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division |

| Campaigns/Battles | Entered the Service From |

| Naples-Foggia campaign | Minquadale, Delaware |

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my previous article about Private 1st Class Frank Kwiatkowski, a friend of Cox’s who was drafted on the same day and attended basic training at the same camp.

Early Life & Family

Frank James Cox was born in Minquadale, Delaware, a suburb south of Wilmington, on April 28, 1923. He was the son of Levi Cox (1897–1969) and Mabel Blanche Cox (1899–1960). He had an older brother, a younger brother and three younger sisters. The Cox family was recorded on the census on April 4, 1930, living on State Road in unincorporated New Castle County southwest of New Castle City. His father was described as a laborer in an iron foundry.

Cox was recorded on the census on April 9, 1940, living with his family in the Farnhurst area. (Farnhurst is another unincorporated area a little to the northeast of the State Road area. The census record stated the family had been in the same place, though not the same house, as of April 1, 1935.) Cox was described as a farmhand with an 8th grade education. The record stated that he had worked 20 weeks during 1939, earning $125, or about $25 a month. Curiously, the census stated he had not worked any hours during the week of March 24–30, 1940, but it did not list him as being unemployed.

Cox may have been recorded a second time on the same census living on Miles Kreider’s farm on New Castle Avenue, located north of New Castle City and just to the east of Farnhurst. If it is the same individual, the data is rather suspect, since it lists him as 19 rather than 16 years old and educated only through the 6th grade. This Frank Cox was described as having worked 40 hours in the past week. The entry said he worked 52 weeks during the previous year rather than 20, earning about $22 a month.

When he registered for the draft on July 13, 1942, Cox was unemployed and living with his parents on Hazeldel Avenue in Minquadale. The registrar described him as standing about five feet, 10 inches tall and weighing 170 lbs., with brown hair and blue eyes.

Cox’s enlistment data card described him as having completed one year of high school and listed his occupation as of February 1943 as “semiskilled occupations in production of industrial chemicals.”

Journal-Every Evening reported that Cox “attended Minquadale and Willard Hall Schools and was employed by the Bond Manufacturing Company before entering the service.” His brother, Levi W. Cox, Jr. (1917–1983), served in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

Military Training

Cox was drafted at the same time as a buddy who also lived on Hazeldel Avenue, Frank Kwiatkowski (1923–1944). Their enlistment data cards stated that they were inducted into the U.S. Army in Camden, New Jersey, on February 18, 1943. Frank Kwiatkowski’s younger brother, Tom, recalls that Cox and Cox’s parents came to pick up his brother to travel to the induction center together. When they tried to leave, the car wouldn’t start back up. Kwiatkowski’s mother took it as an omen that the men would not return, remarking, “Oh my God, that’s a bad sign.”

The men must have stuck together in line at the induction center, since Cox’s service number was one digit higher than Kwiatkowski’s. The men were briefly stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey. On February 27, 1943, Private Cox wrote the first of at least ten letters to his comrade’s sister, Bernice Kwiatkowski. Cox wrote that he and Private Kwiatkowski were in the same company at Fort Dix.

The two men attended basic training in the same training battalion at Camp Wolters, Texas. Private Cox was in 3rd Platoon, Company “D,” 60th Infantry Training Battalion, while Private Kwiatkowski was a member of 3rd Platoon, Company “C.”

Cox wrote to Bernice Kwiatkowski from Camp Wolters on March 24, 1943, that “I have been taking good care of [Frank Kwiatkowski] so far. We are going to town this week end.” In another letter four days later, he wrote:

Well we were out on the rifle range thursday and friday and I didn’t do so bad. Frankie [Kwiatkowski] and the rest of the Battalion went on a hike Saturday and I didn’t have to go cause I was on detail out on the range. We went out there in the morning and they didn’t need us till after dinner so they sent us back. There was six of us. When we got back everybody had left for the hike in full [field gear] on their backs so we just sat around until dinner then when they came back from the hike we just layed on our bunks and laughed at them when they came tramping in, looked like most of them was just about dead and they was really sweating[.]

Cox sent her a photograph of himself, self-deprecatingly suggesting in a letter on April 19, 1943, “I thought that you could keep the rats out of the cellar with it.” He asked for a photo of her in return, adding:

I have always liked you but was never able to get the nerve up to tell you so […] when I get a furlough I am going to come up to you[r] house and get down on my knees and ask you to go out with me. I guess you think I am crazy but I am not, I just can’t think of any other way to ask you to go out[.]

Little did Cox know that his friend, Frank Kwiatkowski, had warned his sister in a letter to his family on March 27, 1943:

Tell Bernice not to take Frank Cox [too seriously.] Because he might make a fool of her. Frank is a good fellow. I like him a lot. But he likes to make fools of girls. So Bernice please watch you[r] self.

On April 19, 1943, Private Cox wrote that he had been on guard duty, claiming facetiously:

If one of our prisoners gets away from us we have to finish serving his time out w[h]ether it is 2 months or 10 years. They won’t get away though cause I have 8 shells in my rifle. If we shoot one of them for trying to escape all we get is a trial for routine then we get a 14 day furlough and get moved to another camp if we want to. I will be hoping that one of them starts running away to try and escape then I know that I will get a furlough. I ought not to wish that though should I[?] I am a l mean little boy aren’t I[?]

He wrote on May 31, 1943: “Well I am feeling pretty good and I have gained 12 pounds since I been in the army. I am not tan, only my hands and face[.]”

After they finished their training, Cox and his buddy ended up in different units. Kwiatkowski joined Company “K,” 115th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, and was killed in Normandy on June 14, 1944.

In a statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission, Cox’s father wrote that his son was stationed at Camp Wolters from March 1, 1943, to April 30, 1943. He added that Cox was briefly stationed at the personnel depot at Camp Shenango, Pennsylvania, before shipping out from Newport News, Virginia, bound for the Mediterranean Theater. Although many soldiers received a brief furlough after completing their training and before going overseas, one of Private Cox’s letters suggested he did not.

Overseas Service

Cox’s father’s statement did not specify when Private Cox went overseas, but Journal-Every Evening reported that he “had been overseas since summer [of 1943], having been sent first to North Africa and then to Italy.”

On July 28, 1943, Cox wrote to Bernice Kwiatkowski: “I am in North Africa someplace but I don’t know where at. I am feeling pretty good right now except for being a little homesick. I sure wish I could have seen everybody before I left.” At the time, he was assigned to Company “B,” 10th Replacement Battalion.

Like most replacements, Private Cox was separated from most of his buddies when he went overseas, though he mentioned that “Reds Bonsall is still with me.” The letter listed the 10th Replacement Battalion as assigned to Army Post Office 776, suggesting that at the time he wrote the letter, he was in or near Casablanca, Morocco.

Cox probably joined Company “C,” 133rd Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division in Tunisia, sometime between July 28 and August 28, 1943. He was promoted to private 1st class sometime between August 28 and September 14, 1943.

Despite his recent promotion, Cox’s last known letter to Bernice Kwiatkowski, dated September 14, 1943, was glum by his standards:

Well I got your letter today and I was sure glad to hear from you. You put some pep in me that I didn’t think I had. I am just about over my homesickness although I would like to be home. But I will get there some day like you say, maybe. […] Maybe after I do get home I will get tired of seeing every body after a while but I sure as heck won’t come back in the army.

Private 1st Class Cox went into combat for the first time during the invasion of mainland Italy in September 1943. The 133rd Infantry captured Benevento in early October 1943. Later that month, the 34th Infantry Division clashed with German forces along the Volturno.

On the night of November 3–4, 1943, the 133rd Infantry’s 1st and 3rd Battalions, with the Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion attached, crossed the Volturno and took their objectives within a few hours despite numerous mines, booby traps, and German resistance. In keeping with their standard doctrine, the Germans soon counterattacked. The 133rd Infantry Regiment history for the month stated: “At daybreak Nov 5th the Regiment suffered a counterattack and the 1st Bn was bushed back from part of its position. However, the Regiment counterattacked with close artillery support, the 1st Bn regaining the high ground it had lost.”

Enemy counterattacks continued during subsequent days, but the 133rd held. Cox’s battalion came out of the line on November 12, 1944. The next 12 days were quiet for the regiment, though they endured a solid week of rain between November 14–21.

The 133rd Infantry relieved the 504th Parachute Infantry near Colli a Volturno during November 24–25, though Cox’s 1st Battalion was initially in reserve. On the morning of November 29, 3rd Battalion and the 100th Infantry Battalion launched an attack against Monte Pantano, with 1st Battalion remaining in reserve. The regiment continued the assault the following day. Though the 133rd took some objectives, German forces stubbornly held onto Hill 832. 1st Battalion “remained in position protecting the right flank of the Regiment.”

Private 1st Class Cox was reported as killed in action on December 1, 1943. A pair of digitized casualty cards (also known as hospital admission cards, though they also documented injuries and deaths where the soldier was not hospitalized) under Cox’s service number from December 1943 likely describe the same event. One card stated that he was wounded in the leg by shell fragments, while the other stated he suffered penetrating trauma in the leg from an artillery shell. Neither card documented whether Cox survived long enough to reach medical treatment, but since no treatment was listed and his status was killed in action rather than died of wounds, he most likely died immediately.

In an article on December 27, 1943, reporting Private 1st Class Cox’s death, Journal-Every Evening stated that Cox’s “parents received a letter from him written Nov. 15 thanking them for his Christmas packages, and a V-mail letter dated Nov. 28, only three days before his death. He had also sent them a check for Christmas.”

Private 1st Class Cox was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

After the end of the war, Cox’s parents requested that his body be repatriated to the United States. Following services at the William F. Jones Funeral Home in Claymont, Delaware, on March 13, 1949, Private 1st Class Cox was buried at Gracelawn Memorial Park in nearby New Castle. He is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle.

Notes

Reds Bonsall

The Reds Bonsall mentioned in Cox’s letter was probably Alpherry S. Bonsall (1924–1990), a Delawarean inducted on the same day as Cox and Kwiatkowski.

Death Location

Regimental records describe the action in which Private 1st Class Cox was killed as occurring on Monte Marrone rather than Monte Pantano. Both are east of Cassino.

Death & Regimental Journal Clues

Instances where the official date of death of a soldier is inaccurate by one or more days are abundant in the records of World War II units, but if Cox was indeed killed on December 1, 1943, he may have been killed while on patrol. The unit journal and after action report do not indicate that 1st Battalion saw any other combat that day.

The regimental journal recorded a 1st Battalion report at 0555 hours on December 1, 1943, that there was no small arms or artillery fire during the night. The battalion had sent out two patrols the night before, but they had not yet returned. A message recorded at 0653 suggested some shooting was heard near the Company “C” position, possibly involving a patrol that departed at 0500.

When the patrol returned, 1st Battalion reported to the regimental S-3 (operations and training officer) that they had been “fired upon at point 025362. Fire came from NW. Enemy estimated to have 3 to 6 Machine guns or Machine pistols and some 81mm mortars.”

One member of the patrol was left at position 023363 but the journal did not reveal his status. The journal recorded a message at 1328 that may refer to that soldier addressed to the 1st Battalion commander: “Did you everget [sic] that wounded fellow back[?]” The commanding officer answered in the negative. An entry from the following day suggests that a patrol found the man dead, but describes him as being from Company “A,” which would tend to rule out him being Cox.

There is no hard evidence that Private 1st Class Cox’s death was related to the patrol documented in the regimental journal. Of course, his death may not have been related to a patrol or attack. The sad reality is that a light bombardment that cost a single soldier his life may not even be mentioned in a combat unit’s report.

It is also possible that Cox was killed earlier but that the quiet day made it possible for the unit to account for recent casualties. Recordkeeping under combat conditions could make it difficult to determine with certainty when a particular soldier fell. Nonetheless, unit morning reports and casualty reports always gave a single date, which usually became the official date of death unless some sort of discrepancy prompted an investigation.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Lisa Kwiatkowski Aretz for the use of photos and letters from her family collection, which included a Frank Cox photo and several letters.

Bibliography

Applications for Headstones, compiled 1/1/1925–6/30/1970, documenting the period c. 1776–1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_520306997_0431-02811

“Claymont Rites Sunday For Pfc Frank J. Cox.” Journal-Every Evening, March 9, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/120706910/frank-j-cox-obit/

Cox, Levi. Frank James Cox Individual Military Service Record, January 3, 1945. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/18244/rec/1

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531891_00334

Marshall, Carley L. “History 133rd Infantry Regiment 34th Infantry Division From 1 November 1943 to 30 November inc.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–48. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Minquadale Man Is Killed in Italy.” Journal-Every Evening, December 27, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/120707017/frank-j-cox-kia/

“Pfc. Frank James Cox.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/50630423/frank-james-cox

Silverman, Lowell. “Private 1st Class Frank Kwiatkowski (1923–1944).” Delaware’s World War II Fallen website, July 16, 2022. https://delawarewwiifallen.com/2022/07/16/private-1st-class-frank-kwiatkowski/

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00546-00609, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00546-00534

The Story of the 34th Infantry Division: Louisiana to Pisa. Information and Education Section, MTOUSA, c. 1944.

U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/702425678/cox-frank-j-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954, https://www.fold3.com/record/702782427/cox-frank-j-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&cat=all&tf=F&q=32751640&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3297567

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, 10/16/1940–3/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_06_00002-00909

Last updated on July 15, 2023

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.