| Hometown | Civilian Occupation |

| Wilmington, Delaware | Clerk for the DuPont Company |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Army | 32481284 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Mediterranean | Company “K,” 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Campaigns/Battles |

| 745 (rifleman) | Battle of Monte Cassino |

Early Life & Family

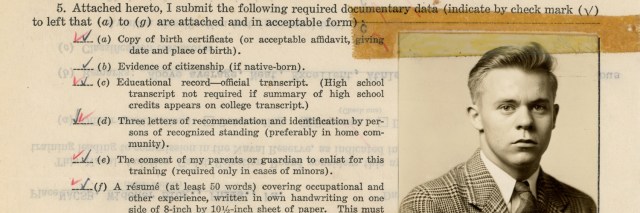

Raymond William Pierson was born at 1804 (North) Tatnall Street in Wilmington, Delaware, on April 13, 1922. He was the only son of John Raymond Pierson (1895–1973) and Loleta Potts Pierson (née Loleta Ruth Potts, 1895–1949).

His father, who went by J. Raymond Pierson, was described as a barber on his son’s birth certificate, though during the 1930 and 1940 censuses he was recorded as a welder at a dye works. The Pierson family was recorded on those censuses living at 804 Tatnall Street. By the time Pierson registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, his family had moved next door to 802 Tatnall Street. The registrar described Pierson as standing five feet, nine inches tall and weighing 135 lbs., with brown hair and eyes. He was Protestant according to his military paperwork.

Pierson’s high school yearbook entry stated: “A future scholar of Beacom College, Ray names as his hobbies marksmanship and bowling. He tells us that he dislikes bad sports and believes all homework should be abolished, and listen, a secret, ice cream and blondes—umm!”

Journal-Every Evening stated:

He was a graduate of Pierre S. duPont High School, class of 1940, had attended Beacom College, and for two and a half years before entering the armed forces he was employed in the purchasing department of the DuPont Company. He was a member of Hanover Presbyterian Church, and was interested in the Christian Endeavor and other young people’s activities.

The paper reported on November 28, 1942, that after Pierson was drafted,

A luncheon was given recently by members of the purchasing department of the DuPont Co., in honor of Raymond W. Pierson and Joseph Calhoun who went into the Army this week. They were presented with wrist watches and other gifts.

In his statement for the State of Delaware Public Archives Commission, J. Raymond Pierson wrote that his son’s occupation was clerk, while the 1942 Wilmington directory described him as a mail room boy.

Military Training

Pierson’s enlistment data card was somewhat garbled when it was digitized, but it appears that he was inducted into the U.S. Army in Camden, New Jersey, on November 10, 1942. His father’s statement suggests that he went on active duty on November 25, 1942.

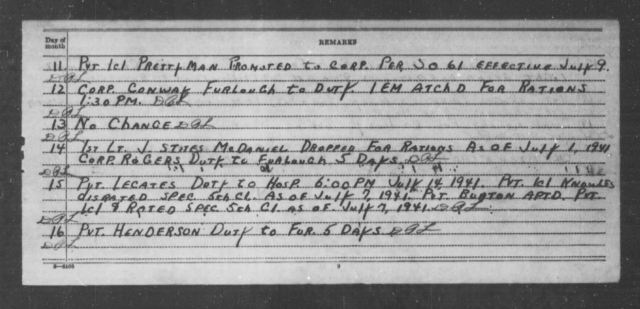

According to his father’s statement, Private Pierson was initially assigned to Company “C,” 301st Infantry Regiment, 94th Infantry Division at Camp Phillips, Kansas. A document in Pierson’s Individual Deceased Personnel File (I.D.P.F.) confirmed that Pierson was with that unit as December 22, 1942. The 301st Infantry had been activated at Fort Custer, Michigan, before moving to Camp Phillips in November 1942. The regiment went on maneuvers in Tennessee in early September 1943. Indeed, Journal-Every Evening reported that Pierson “was in maneuvers in Tennessee” prior to going overseas.

In the fall of 1943, Private Pierson transferred out of the 301st Infantry, apparently for transfer overseas as a replacement. His father wrote that Pierson was stationed at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, beginning on October 8, 1943. He was presumably assigned to Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot No. 1 there. A document in Pierson’s I.D.P.F. stated that Pierson was assigned to the Casual Detachment at Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, during November 15–18, 1943, probably before his departure from the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation. That’s consistent with J. Raymond Pierson’s statement, which advised that Private Pierson shipped out from Newport News, Virginia, on November 20, 1943. By January 1943, he was in Italy.

Battle of Monte Cassino

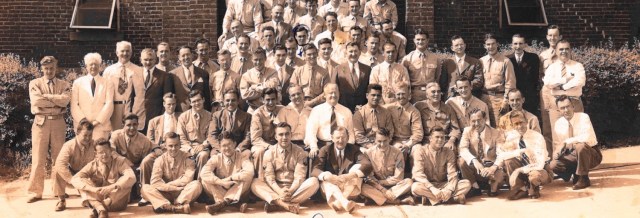

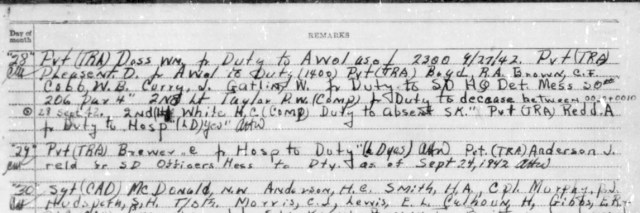

On January 17, 1944, Private Pierson and 32 other enlisted men joined Company “K,” 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division. Two-thirds of these replacements, including Pierson, were riflemen. According to the regimental history, the 168th Infantry had just gone into reserve the night before “after 13 days and nights of continuous attack against constant opposition.”

At the time Pierson joined the 168th Infantry, the Allies and Germans were locked in grueling combat near Cassino along the Germans’ Gustav Line. Pierson was fortunate to have about a week to acclimate to his new unit before going into combat for the first time, since it was not uncommon for replacements to join units already in the line and be killed before their new comrades even learned their names. The unit history stated: “During the following 8 days, the Regiment rested and trained in preparation for the assault on the Gustav line, which was to begin on January 27.” This assault was part of what would be come to be known as the Battle of Monte Cassino (known as First Battle of Monte Cassino in some sources, which refer to it as a series of four battles).

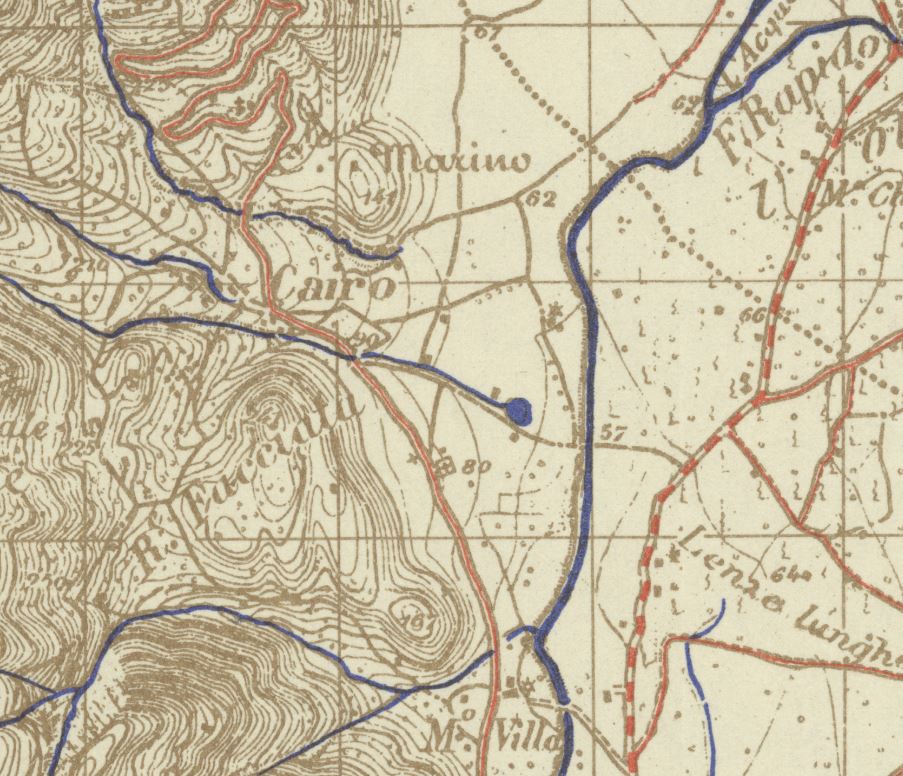

Journal-Every Evening reported that “The last letter received by Mr. and Mrs. Pierson from their son was dated Jan. 24 in which he assured them he was well and ‘all right.’” According to the regimental history, that night the 168th Infantry “moved from bivouac areas near Cervaro to the vicinity of S[an] Michele. At dusk on the following day, the 1st and 3rd Battalions moved up to assembly areas two to three thousand yards from the [Rapido] River[.]”

The 168th Infantry’s objectives were a pair of fortified hills to the west of the river. The regimental history stated:

[The] system of enemy defenses before Hills 56 and 213, prepared over a period of several months, was exceedingly strong. Along the base of the hills was a line of pillboxes, dugouts, and reinforced stone houses. From these positions, the enemy had fields of fire which completely covered the flats between the river and the base of the hill. In order to increase the effectiveness of their fire, they had cut all of the trees and brush from the river to the hill. Stumps three feet high were left as minor tank obstacles. A system of anti-personnel mine fields, inter-locked with barbed wire entanglements, completely covered the flats before the hills to a depth of 300 to 400 yards beyond the river bank.

The local defenses were especially vulnerable to armor because the Germans had run out of time to place antitank mines. As an expedient, the enemy had blown a dam, “diverting the course of the Rapido River. The natural tank approach along the road running into Cassino from the north was flooded to a depth of 1 to 2 feet.”

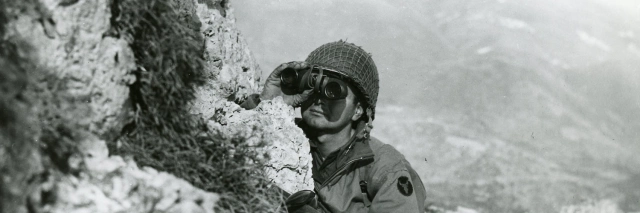

The attack began on the morning of January 27, 1944. Allied artillery pounded the German side of the river for an hour. At 0730 hours, American tanks advanced under cover of a rolling barrage with elements of 1st and 3rd Battalions close behind. American engineers built a corduroy road (log road) for the tanks to cross the flooded areas. In Private Pierson’s 3rd Battalion, Company “L” was first across the river, followed by Company “I.” Pierson’s Company “K” remained on the near side of the river as the attack bogged down. Three of the four tanks that made it across were knocked out and the infantry sustained heavy losses.

Originally, Company “K” was supposed to pass through the other two companies from 3rd Battalion to continue the attack, but the American leadership decided to reconnoiter the area to the north to find a more favorable route to pierce the German defenses. That night, Company “I” returned across the river and linked up with Company “K.” The unit history continued:

With one platoon from each company in the lead, this group crossed the river about 500 yards to the north of the tank crossing. With the help of a French guide, they advanced through the mine field without opposition to the cross road at RJ 74. The two leading platoons dug in around this cross road, and the balance of the two companies remained in the river bed.

During the hours of daylight on January 28, the 1st and 3rd Battalions remained in their positions. Under heavy shell fire, the engineers attempted to improve the tank crossing, without much success.

The next day’s push would be maximum effort: All three of the 168th Infantry’s battalions would attack. 2nd Battalion, which had been in reserve during the first two days of the battle, would lead the way after passing through the other two battalions’ positions. The infantry would have support from elements of 756th and 760th Tank Battalions, as well as elements of the 175th Field Artillery Battalion, the 34th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, the 109th Medical Battalion, the 109th and 235th Engineer Combat Battalions, and the 1108th Engineer Combat Group.

The renewed attack began on the morning of January 29, 1944, when seven tanks crossed the Rapido. Four were soon knocked out and the situation worsened when the tank crossing became blocked by a stuck tank. 2nd Battalion of the 168th Infantry initially made limited headway and the 1st and 3rd Battalions remained stationary. That afternoon, however, the Americans finally broke the deadlock when the 756th Tank Battalion got 23 tanks across the Rapido at another crossing site prepared by engineers to the north. Eight tanks supported 1st Battalion, nine joined 2nd Battalion, and the six linked up with 3rd Battalion.

With the help of the armor, the rest of the attack went like clockwork. As the author of the regimental history wrote:

The actual assault against the hill has been described by the company commander of the leading company to have been almost a maneuver by the field manual. There was very little machine gun fire, since by firing, the enemy would have disclosed their positions to the tanks. The battalions in columns followed in the tank tracks to the base of the hill.

The elaborate defenses of Hills 56 and 213 were over-run in a coordinated attack by infantry and tanks. It seems evident that if the German defenses had been strong enough to hold off the tanks, the attack could nothave [sic] been made.

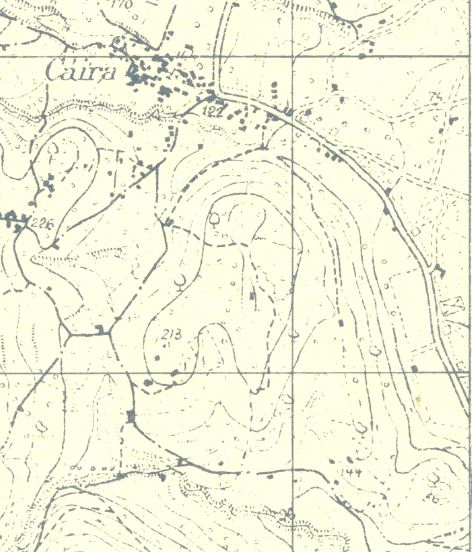

After sunset, 1st Battalion continued their advance on Hill 56 while 2nd and 3rd Battalions captured Hill 213. The attack continued into the early morning hours of January 30, 1944, when Company “I” and Private Pierson’s Company “K” “occupied the so[u]thern end of Hill 213.” Later that morning, a platoon from Company “K” and a platoon of 760th Tank Battalion tanks captured Caira, securing the 168th Infantry’s right flank. More hard fighting followed during February 1944, but the Allies would not decisively break through the Gustav Line until May.

Private Pierson was reported as killed in action on January 29, 1944. If accurate, it was just his third day at the front. His burial report stated that Pierson was shot in the chest and killed near Cairo, Italy. (It seems likely that this should have been Caira. See the Notes section for further details about map discrepancies.)

Pierson’s personal effects included a wristwatch—perhaps the one gifted by his coworkers at DuPont—two rings, a pocketknife, a mechanical pencil, a notebook, and several letters.

Private Pierson was initially buried in a temporary military cemetery at Marzanello Nuovo on February 8, 1944. After the war, in 1947, Pierson’s father requested that his son be repatriated to the United States. Private Pierson’s body was disinterred on June 24, 1948, and returned from Naples to the New York Port of Embarkation aboard the U.S.A.T. Carroll Victory. A military escort accompanied Private Pierson’s casket by train, arriving in Wilmington on September 29, 1948.

After services at the McCrery Funeral Home in Wilmington on October 2, 1948, Private Pierson was buried at Union Hill Cemetery in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. His parents were also buried alongside him after their deaths.

Notes

Location Notes

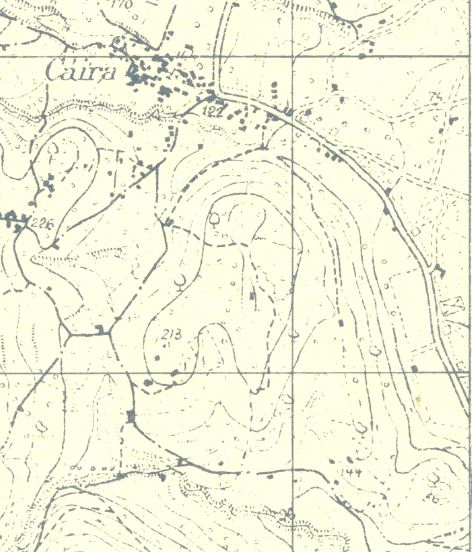

Hills were known by their heights in meters as labeled on military maps. Under most circumstances, that would imply that Hills 56 and 213 were 56 meters and 213 meters high. However, there were significant discrepancies in the maps of Italy used by the U.S. Army at the time.

The 1/50,000 map (160-I) referred to the town as Cairo rather than Caira and marked the heights of the hills to the south as 241 and 167. The 1/25,000 map (160-I-SW) gave the name of the town as Caira and the hills as 213 and 56. 213 was not a label for the actual summit of the hill and based on the terrain contours, 56 was likely a typo that should have been 156. Although the map names imply one consistent system subdivided into increasingly detailed maps, they were copies of Italian maps. The original maps were often out of date. Furthermore, maps of the same areas in different scales area were sometimes created years apart.

Bibliography

“Delawareans in the Service On Land On Sea and In the Air.” Journal-Every Evening, November 28, 1942. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/118179625/pierson-farewell-party/

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531893_00144

Morning reports for Company “K,” 168th Infantry Regiment. January 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Narrative of the Action of the 168th Infantry Regiment January 1, 1944 to January 27, 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

“Narrative of the Action of the 168th Infantry Regiment January 24, 1944 to February 29, 1944.” World War II Operations Reports, 1940–1948. Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905–1981. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

The Pierrean January 1940. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1265/images/1265_b696940-00012

Pierson, John Raymond. Raymond William Pierson Individual Military Service Record, c. 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware.

Polk’s Wilmington (New Castle County, Del.) City Directory 1942. R. L. Polk & Company Publishers, 1942. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/16105759

“Pvt. Raymond W. Pierson.” Wilmington Morning News, September 30, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/118177863/raymond-pierson-obit/

“Pvt. Raymond William Pierson.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53855507/raymond-william-pierson

Raymond W. Pierson Individual Deceased Personnel File. Courtesy of U.S. Army Human Resources Command.

Raymond William Pierson birth certificate. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DYQ9-WBB

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/m-t0627-00551-00633

U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942–1954. Record Group 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775–1994. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/record/704802503/blank-us-wwii-hospital-admission-card-files-1942-1954

“Wilmington Soldier, Sailor Reported Killed in Action.” Journal-Every Evening, March 2, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/118178676/pierson-killed-in-italy/

World War II Army Enlistment Records. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=2&cat=all&tf=F&q=32481283&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=3092870&rlst=3092869,3092870

WWII Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, 10/16/1940–3/31/1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44003_10_00006-01411

Last updated on June 14, 2023

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.