| Home State | Civilian Occupation |

| Delaware | Physical education teacher |

| Branch | Service Number |

| U.S. Marine Corps Reserve | 951463 |

| Theater | Unit |

| Pacific | Company “B,” 24th Marines, 4th Marine Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Iwo Jima |

| Military Occupational Specialty | Entered the Service From |

| 745 (rifleman) | Newark, Delaware |

Early Life & Family

Roland Pusey Jackson was born in Newark, Delaware, on March 30, 1913. He appears to have been the only child of Henry Roland Jackson (1891–1972) and Hannah Virginia Jackson (1895–1973, née Fulton). Nicknamed “Boney,” Jackson grew up in Newark. He was recorded on the census on April 14, 1930, living with his parents on East Park Avenue (presumably the street known today as East Park Place). He was Methodist.

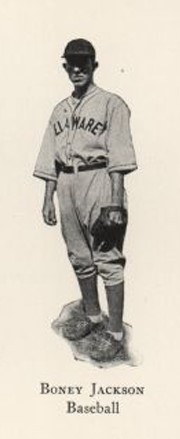

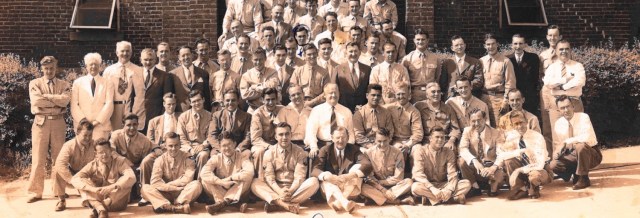

After graduating from Newark High School, Jackson attended the University of Delaware. He spent two years in the U.S. Army’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (R.O.T.C.) program there. Jackson also played baseball, basketball, and soccer in college, though it appears baseball was the only sport that he played at the varsity level. One of Jackson’s yearbooks noted that his freshman year, 1934, “Ferguson, Jackson, and Minner were the outstanding performers for the Blue and Gold nine during the season.” One of his baseball teammates was Ferris Leon Wharton (1915–1944), who like Jackson would also become a physical education teacher before joining the Marine Corps. Interestingly, their 1937 yearbook noted: “Four teams subdued the Hens in close games, all played within a week’s time, but they finally managed to pull out of the slump to thoroughly whip the Quantico Marines in a slugfest” 12–4. Jackson graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Physical Education in June 1938.

Jackson was recorded on the census in April 1940, living with his parents at 32 Center Street and working for a paint manufacturer. Indeed, Jackson later told the Marine Corps that he worked for one year as a burner man for E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company—better known as the DuPont Company—in Edgemoor, Delaware, where he calcined pigments and regulated their temperatures, earning $41 per week. One of Jackson’s neighbors at the time was 16-year-old Robert Gage Allen (1923-1945). Allen, who lived at 24 Center Street, died during an operation to retake Corregidor in the Philippines just three days before Jackson landed on Iwo Jima.

Jackson’s hobbies included hunting and fishing.

A January 13, 1939, news item in Journal-Every Evening announced Jackson’s engagement to Josephine Ann George (1916–1991). The couple married in Newark on September 21, 1940. Jackson’s occupation was listed as millwright. Presumably he was still with the DuPont Company, the employer recorded when he registered for the draft the following month.

Jackson and his wife had one son, Roland Lamont “Monty” Jackson (1942–2009).

When Jackson registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, he was living at 52 North Street in Newark. The registrar described him as standing six feet, one inch tall and weighing 185 lbs., with brown hair and eyes.

The family moved to 33 West Cleveland Avenue before Jackson was drafted. A February 12, 1943, news item in Journal-Every Evening announced that Jackson had been hired as a physical education instructor at Newark High School. Jackson told the Marine Corps that he earned $42 per week in his new job. That fall, Jackson coached the school football team, known as the Yellowjackets, to a 5–3 season. Early the next year, he was drafted along with a group of men including N.H.S. music teacher Frederick B. Kutz (1907–1976).

Military Career

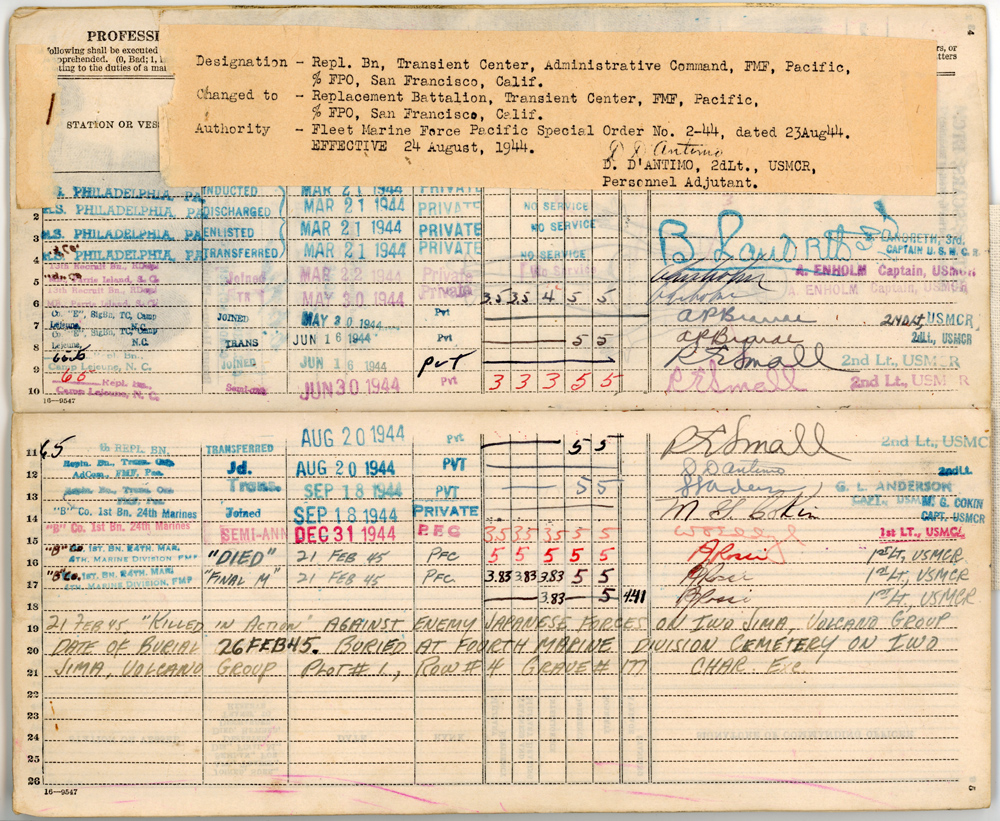

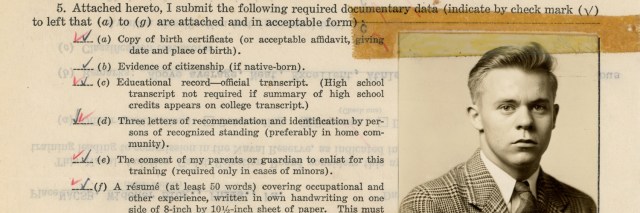

In early 1944, Jackson was examined by Wilmington Board No. 4, which classified him I-A on January 28, 1944. According to his personnel file, after Jackson was drafted that March, he reported at the induction center in Camden, New Jersey, where he listed the Marine Corps as his service of choice.

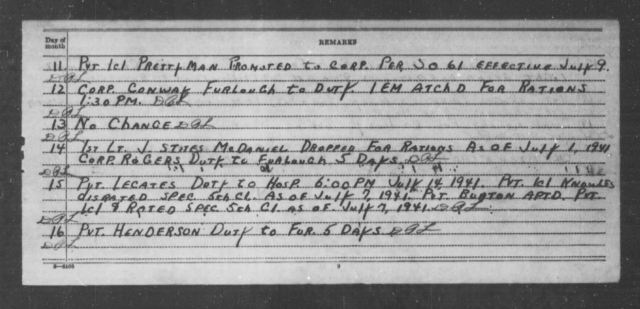

Jackson joined the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on March 21, 1944. He and a group of other recruits departed Philadelphia by train that afternoon, arriving the following day at Parris Island, South Carolina, where he was assigned to the 13th Recruit Battalion. The Marine classifier recommended Jackson for field telephone training. After graduating from boot camp on May 30, 1944, he was transferred to Company “E,” Signal Battalion, Training Center, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, where he awaited the beginning of a training class. His military occupational specialty (M.O.S.) at the time was recorded as 521, basic. However, that training still had not begun by June 16, 1944, when he was transferred to the 65th Replacement Battalion, also at Camp Lejeune.

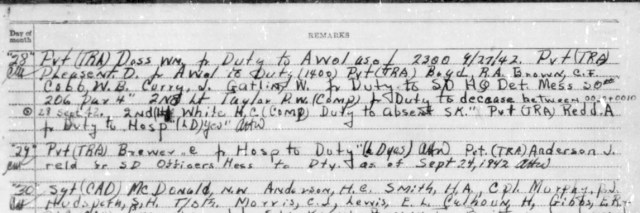

Private Jackson went on furlough from June 22, 1944, through July 2, 1944. His Marine Corps qualification card indicated that in July 1944 Jackson was classified with M.O.S. 604, light machine gunner, though muster rolls later described him as a basic again when he joined his final unit. The following month, on August 3–4, 1944, his unit departed Camp Lejeune by train, arriving in San Francisco, California, on August 8–9.

On August 10, 1944, the 65th Replacement Battalion shipped out for Hawaii aboard a U.S. Army transport, U.S.A.T. Santa Isabel. The ship arrived at Pearl Harbor on August 17, 1944. Three days later, Private Jackson transferred to the Replacement Battalion, Transient Center, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific. He remained there until September 18, 1944, when he joined Company “B,” 1st Battalion, 24th Marines, 4th Marine Division (also referred to as Baker Company or B/1/24). Despite the replacements, the battalion was still understrength by the time it returned to combat five months later.

Geoffrey Roecker, who has written extensively about the history of 1st Battalion, 24th Marines in World War II, told me that “Jackson had a few months of training with B/1/24 at Camp Maui – the overseas home of the 4th Marine Division.” On October 18, 1944, Jackson’s M.O.S. changed to 745, rifleman. That same month, on October 26, 1944, Jackson was promoted to private 1st class.

On January 3, 1945, Private 1st Class Jackson boarded the attack transport U.S.S. Hendry (APA-118) on Kahului, Maui. The ship sailed for Pearl Harbor the following day, arriving on January 5, 1945. Hendry transported the marines on maneuvers on January 7–8 and January 13–17.

On the morning of January 27, 1945, U.S.S. Hendry sailed from Pearl Harbor as part of a convoy bound for the Mariana Islands. After a brief stop for fuel and provisions at Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands, the convoy arrived at Saipan on February 11, 1945. A report about U.S.S. Hendry’s operations during the invasion of Iwo Jima stated that after the vessel “Conducted exercises in ship to shore movement off Tinian on 13 and 14 February, 1945” before the transport sailed for Iwo Jima on February 16.

Roecker wrote in his article, “Hell. Iwo Jima: 19 February 1945,” that

Every day aboard the Hendry, the platoons received briefings on a relief map of the island, lectures on field sanitation and chemical warfare, learned basic first aid from the corpsmen, stood weapons inspections, and did as much physical training as they could in the cramped space aboard ship. The battalion officers drilled the ship’s small boat officers relentlessly to make sure their men would get ashore safely.

The Battle of Iwo Jima

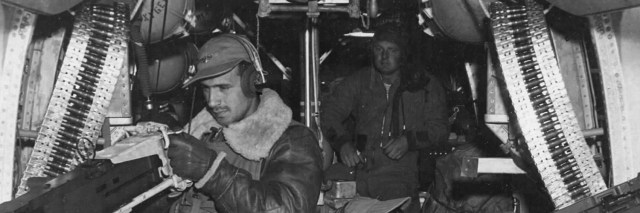

A small volcanic island located midway between the Mariana Islands and Japan took on outsize importance in early 1945. The island held promise as a base for fighters to escort B-29 Superfortresses during air raids on the Japanese Home Islands, as well as a diversion airfield for those bombers. The Japanese garrison could have no hope of victory but they were determined to maximize American casualties before the inevitable happened.

More Marines from Delaware died on Iwo Jima than on Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Tinian, Guam, and Okinawa combined. In fact, of the 35 Delawareans who died serving in the Marine Corps during World War II, 14 were killed on Iwo Jima.

Henry arrived off the coast of Iwo Jima on the morning of February 19, 1945. She had 1,426 Marines aboard, including 214 from Private 1st Class Jackson’s company. Despite the intense bombardment of the island by air attack and naval gunfire, most Japanese fortifications were still intact when Marines began landing around 0900 hours. As the division reserve, the 24th Marines remained aboard ship at the outset of the battle. Jackson may have watched from the deck of his transport as the first wave of Marines struggled ashore.

Roecker wrote that at 1448 hours, 1st Battalion received orders to land immediately. It took less than one hour to load and launch the landing craft, despite the transport briefly coming under Japanese artillery fire. The men of 1st Battalion began landing at Beach Blue on Iwo Jima at approximately 1625 hours on February 19, 1945. The bodies of men from the 25th Marines, cut down when they landed that morning, were strewn across the beach.

Private 1st Class Jackson’s Company “B,” 24th Marines pushed inland and relieved Company “L,” 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines, digging in on a ridge taken at high cost. Casualties in Jackson’s company (four wounded, of whom two later died) were light in comparison to what was to come in the days that followed. Japanese artillery fire continued throughout the night and small groups of enemy soldiers probed the Marine lines.

Geoffrey Roecker wrote in his article, “Basin. Iwo Jima: 20 February 1945,” that on February 20, 1945, some men from Jackson’s company were able to destroy a Japanese bunker with a can of gasoline and a thermite grenade. Roecker continued:

Unfortunately, the immolation of the ammunition bunker would be one of Baker Company’s only successes for the day. Their commanding position was highly visible to the Japanese, who mercilessly pounded the blockhouses with mortars and small arms. Going outside was not a welcome option, but orders were orders and the company gamely tried to advance. “We tried to get off the ridge and gain some ground, we would gain a hundred yards, and then we would have to fall back up the ridge where we had some protection,” recalled PFC Charles Kubicek. “A hundred yards was a big move back then.”

Jackson’s company also came under friendly air and naval gunfire by mistake. Company “B” casualties for the day were two dead and 27 wounded. For the second night in a row, the Marines endured both Japanese artillery fire and attacks by small groups of Japanese infiltrators.

Geoffrey Roecker wrote in his article, “Basin. Iwo Jima: 20 February 1945,” that on February 20, 1945, some men from Jackson’s company were able to destroy a Japanese bunker with a can of gasoline and a thermite grenade. Roecker continued:

Unfortunately, the immolation of the ammunition bunker would be one of Baker Company’s only successes for the day. Their commanding position was highly visible to the Japanese, who mercilessly pounded the blockhouses with mortars and small arms. Going outside was not a welcome option, but orders were orders and the company gamely tried to advance. “We tried to get off the ridge and gain some ground, we would gain a hundred yards, and then we would have to fall back up the ridge where we had some protection,” recalled PFC Charles Kubicek. “A hundred yards was a big move back then.”

Jackson’s company also came under friendly air and naval gunfire by mistake. Company “B” casualties for the day were two dead and 27 wounded. For the second night in a row, the Marines endured both Japanese artillery fire and attacks by small groups of Japanese infiltrators.

Roecker wrote in “Quarry. Iwo Jima: 21 February 1945” that Companies “A” and “B” were ordered to make another advance against Japanese fortifications on the morning of February 21, 1945:

Captain William A. Eddy’s boys stepped off on schedule at 0935. […] To their front were the Japanese, who greeted them with rifle, light machine gun, and mortar fire. Baker Company had a bone in its teeth that morning, and by 1000 had advanced the nigh-unthinkable distance of 200 yards. From their new vantage point, they could see Japanese soldiers well emplaced in caves along a ridge to their right front. More immediate danger came from the enemy soldiers they could not see, some of whom launched 50mm grenades from short-range “knee mortars” while others targeted the company with heavy mortars. The attack, which slowed under the rain of bombs at 1100, picked up steam again in the early afternoon, but for all their efforts, “the enemy resistance did not decrease.”

Sometime during the day’s combat, Private 1st Jackson was struck in the head by a shell fragment and killed. The day’s combat cost Baker Company an additional one dead and 28 wounded. Roecker wrote:

Roland Jackson and Gilbert Miller lay dead under bloody ponchos. There was no cemetery yet – there was no time, or space, or detail available to make one – so the dead were simply laid out in neat rows, or stacked like cordwood, in ever-increasing numbers.

Of the 214 Company “B” men who landed on Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, 28 were killed (13%) and another 140 wounded (65%) during one month of combat. Including casualties suffered by the 69 men who joined the company as replacements during the battle, Baker Company lost 42 dead, 169 wounded, and 2 sick, totaling 75% casualties.

Jackson’s personal effects included his wallet, Social Security card, several rings including his wedding band, a broken identification bracelet, and 17 photographs.

Private 1st Class Jackson was initially buried at the 4th Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima. Jackson’s wife Josephine learned of her husband’s death in a telegram by March 29, 1945, when the news was printed in Journal-Every Evening. After the war, his body was returned to the United States and buried at the Baltimore National Cemetery in Maryland on June 10, 1948. His widow, Josephine, did not remarry.

Jackson’s name is honored at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware, as well as on both the Newark and University of Delaware World War II memorials.

Notes

Date of Birth

As originally published, this article gave Jackson’s date of birth as March 30, 1913, the date listed on his headstone at Baltimore National Cemetery. However, overwhelming evidence establishes that his date of birth was March 30, 1914, the date listed on his birth certificate, draft card, Marine Corps personnel file, and in Social Security Administration records. In particular, his birth certificate would seem to be authoritative since it was filed in 1914, not 1913.

Jackson’s Father

Jackson’s father worked at the Continental Diamond Fibre factory, eventually rising to foreman and then inspector. He retired from the Budd Company after it acquired the factory.

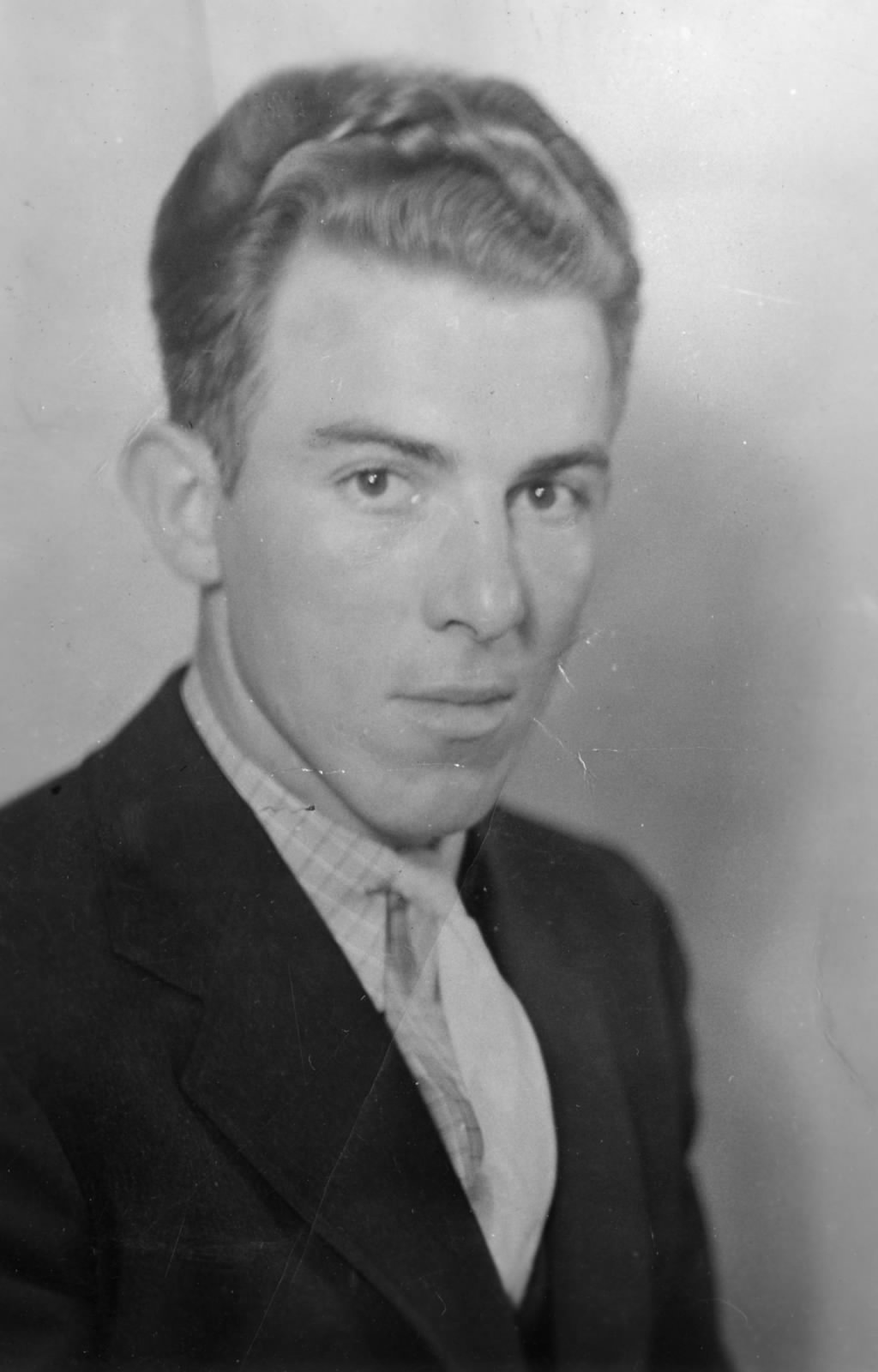

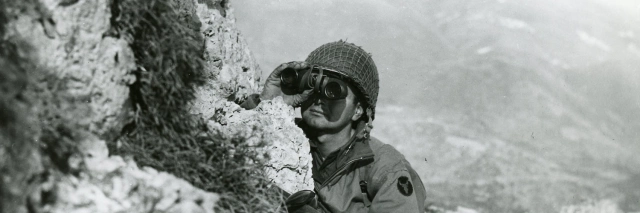

Photo Enhancement

The photo at the top of this page was digitally enhanced using tools on the genealogy website MyHeritage. This software is useful in instances where the only known photograph is of limited resolution (in this case, because the original print was fuzzy and had to be photographed through glass of a collage displayed at the Newark History Museum). I believe this to be an accurate reconstruction, but the software could potentially introduce errors by misinterpreting fuzzy details in the original photograph. A comparison of the original and enhanced versions of the photos can be viewed below.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Geoffrey Roecker, Webmaster & Lead Researcher at Missing Marines as well as The First Battalion, 24th Marines website, for providing extensive information about the last four months of Private 1st Class Jackson’s life. Thanks also to the Newark History Museum and Delaware Public Archives for the use of their photographs.

Bibliography

“17 Delaware Men Become War Casualties.” Journal-Every Evening, March 29, 1945. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65608348/roland-jackson-casualty/

Blue Hen of 1935 and 1936. 1936. https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/e3807d46-7aa2-467d-8485-773f6a1db6eb/content

The Blue Hen for 1937–1938. 1938. https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/d0403035-a186-496f-ba99-4d65358394af/content

Census Record for Roland Jackson. April 10, 1940. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89MR-MRS

Census Record for Roland P. Jackson. April 14, 1930. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9R4B-DB3

Certificate of Birth for Roland Pusey Jackson. April 7, 1914. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-D4S4-8

Certificate of Marriage for Roland P. Jackson and Joseph A. George. September 21, 1940. Delaware Marriages. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6Y2D-ZF

Draft Registration Card for Henry R. Jackson. June 5, 1917. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005207029_04237

Draft Registration Card for Roland Pusey Jackson. October 16, 1940. Draft Registration Cards for Delaware, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMG-X9B3-H

“Elkton Marriages.” Every Evening, January 13, 1914. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65677095/roland-jacksons-parents-wedding/

Interment Control Form for Roland Pusey Jackson. July 12, 1948. Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_646933_0467-00628

“Henry R Jackson.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/206692769/henry-r-jackson

Jackson, Josephine G. Individual Military Service Record for Roland Pusey Jackson. March 3, 1946. Record Group 1325-003-053, Record of Delawareans Who Died in World War II. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://cdm16397.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15323coll6/id/19340

“Josephine Ann ‘Phine’ Jackson.” The News Journal, August 25, 1991. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65608806/josephine-ann-jackson/

Krawen 1943. 1943. Courtesy of the Newark History Museum.

Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1803–1958. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272234-00267 (March 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272248-00266 (April 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_267635-00271 (May 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272382-00292, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272157-00559 (June 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272398-00494 (July 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269714-00539 and https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269714-00548 (August 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269736-00539 (September 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_269339-00491 (October 1944), https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1089/images/33068_272282-00861 (January 1945)

“Newark.” Journal-Every Evening, February 12, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65608212/roland-jackson-nhs/

“Newark Opens Football Drills.” Journal-Every Evening, September 14, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65608162/roland-jackson/

“Newark Wins Over Conrad.” Journal-Every Evening, November 26, 1943. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65679107/yellowjackets-1943-season-end/

Official Military Personnel File for Roland P. Jackson. Official Military Personnel Files, 1905–1998. Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Police, Firemen, Teachers Listed Among Inductees.” Wilmington Morning News, March 30, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65614669/roland-jackson-drafted/

Roecker, Geoffrey. “Baker.” The First Battalion, 24th Marines website. https://1-24thmarines.com/personnel-2/baker/

Roecker, Geoffrey. “Basin. Iwo Jima: 20 February 1945.” The First Battalion, 24th Marines website. https://1-24thmarines.com/the-battles/iwo-jima/d1/

Roecker, Geoffrey. “Hell. Iwo Jima: 19 February 1945.” The First Battalion, 24th Marines website. https://1-24thmarines.com/the-battles/iwo-jima/dday/

Roecker, Geoffrey. “Quarry. Iwo Jima: 21 February 1945.” The First Battalion, 24th Marines website. https://1-24thmarines.com/the-battles/iwo-jima/d2/

“Roland L. Jackson ‘Monty.’” The News Journal, April 4, 2009. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65607980/obituary-for-roland-l-jackson-son-of/

“Swedish Leaders Are Honored with U. of D. Degrees.” Wilmington Morning News, June 7, 1938. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65616194/jackson-graduation-ud/

“Their Engagements Announced.” Journal-Every Evening, January 13, 1939. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/65614375/jackson-george-engagement/

Welles, R. C. “General Action Report, Submission of.” March 5, 1945. World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/295856754

Last updated on February 22, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.