| Residences | Civilian Occupation |

| New Jersey, Delaware | Worker at Pusey & Jones shipyard |

| Branch | Service Numbers |

| U.S. Army | U.S. Navy 2438867 / U.S. Army 32756930 |

| Theater | Unit |

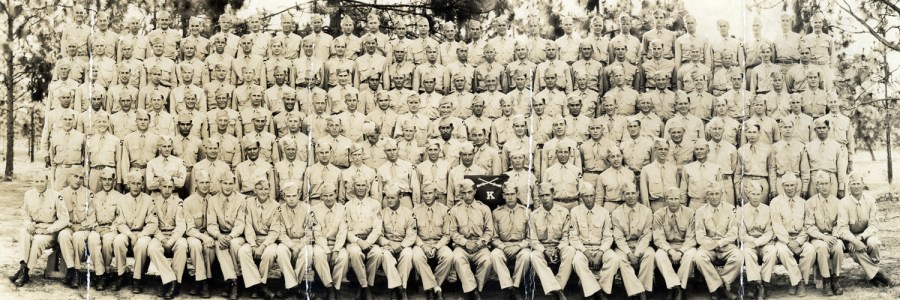

| European | 4th Platoon, Company “K,” 333rd Infantry Regiment, 84th Infantry Division |

| Awards | Campaigns/Battles |

| Purple Heart | Rhineland |

Author’s note: This article was originally published on June 18, 2021, but was substantially rewritten on December 31, 2023, to incorporate details obtained at the National Archives in St. Louis from Henderson’s U.S. Navy personnel file and a company morning report, as well as additional information about his early life from Delaware records. It was updated again on April 1, 2025, incorporating information from his last payroll record.

Early Life & Family

Robert DuBois Henderson was born in Cumberland County, New Jersey, in either Cedarville or nearby Bivalve, on December 5, 1923. He was first child of John Griffith Henderson (a fisherman, 1898–1972) and Ruby Taylor Henderson (née Ruby Pearl Henderson, 1906–1935).

The Henderson family had moved to 521 West 2nd Street in Wilmington, Delaware, by October 1, 1925, when Henderson’s younger brother, John Edward Henderson (1925–2000), was born. Henderson was recorded on the census on April 11, 1930, as living with his mother and brother at 409 Marsh Road in Wilmington. Henderson’s mother died at St. Francis Hospital in Wilmington on October 2, 1935, attributed to lobar pneumonia and delirium tremens. Although her death certificate gave her residence as “21 Robinson St”—not an extant address, but presumably located in Wilmington since no other city was specified—her obituary indicated that Henderson, his father, and brother were living back in Bivalve by that point.

According to his U.S. Navy personnel file, Henderson dropped out of school after completing the 7th grade, while the 1940 census stated that he finished the 8th grade. At the time of the 1940 census, recorded on April 27, 1940, Henderson was living on Church Street in Bivalve at the home of his grandmother, Jennie Henderson, along with his aunt and uncle, two cousins, and four lodgers. Henderson was residing on Chester Street in Bivalve, possibly still living with his grandmother, by the time he applied to join the Navy in early 1941.

Naval Service

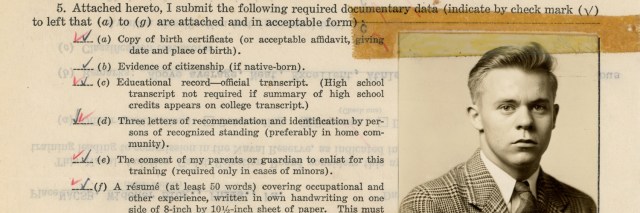

On January 17, 1941, shortly after his 17th birthday, Henderson applied to join the U.S. Navy. His father, by then living in Morgan City, Louisiana, consented to his son’s enlistment. Henderson stated that he intended to make the Navy a career and was accepted as an apprentice seaman in the U.S. Navy in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on March 5, 1941. The following day, he reported for boot camp at the U.S. Naval Training Station, Newport, Rhode Island. Upon entry to the Navy, his personnel file described him as standing five feet, 5¼ inches tall and weighing 135 lbs., with brown hair and blue eyes.

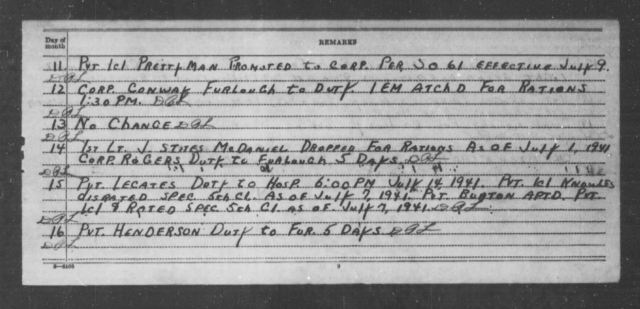

Henderson was promoted to seaman 2nd class on July 4 or 5, 1941. Later that month, on July 30, 1941, he was transferred to the U.S. Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois, reporting for duty the following day. On August 4, 1941, Seaman 2nd Class Henderson began the Group III Basic Course there. According to his personnel file, on August 28, 1941, Henderson “Transferred for temporary duty at the Navy Service School, Ford Motor Company, Dearborn, Mich., for specialized instruction in Subgroup IIIa (Machinist).”

Henderson’s father enlisted in the U.S. Navy a few months after his son, on July 7, 1941. Apparently due to his extensive experience at sea, the elder Henderson did not have to work his way up through the ranks but was immediately appointed chief boatswain’s mate. He remained in the service through the end of the war. Henderson’s brother also served in the Navy during 1944–1946.

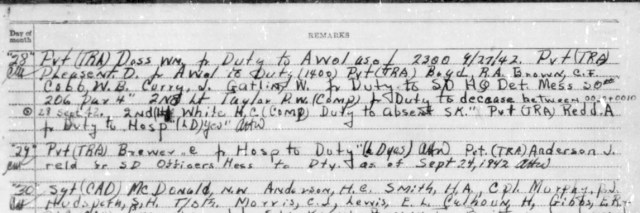

Although it was still months until his 18th birthday, Seaman 2nd Class Henderson was well on his way to becoming a petty officer. In the fall of 1941, however, Henderson began demonstrating a streak of poor discipline which would eventually ruin his naval career. Henderson was about two hours A.O.L. (absent over leave or liberty). The punishment for this first infraction was mild. At a captain’s mast on October 2, 1941, Henderson lost a week’s liberty. However, soon after, he left his “post of duty while on Seaman Patrol.” At a captain’s mast on November 5, 1941, he was punished with the loss of three weeks’ liberty. Just three days later, he went absent without leave (A.W.O.L.) for nearly 38 hours, until the night of November 8, 1941.

Upon Henderson’s return, he was immediately subjected to a captain’s mast. This time, the consequences were severe. His commanding officer punished him with five days’ confinement on bread and water and dismissed him from the school on the grounds that he was not a suitable candidate to become a petty officer. On his 18th birthday, December 5, 1941, Henderson was dispatched to the Receiving Station, Boston, Massachusetts, for further duty aboard the old battleship U.S.S. Mississippi (BB-41), which had been performing convoy escort duties with the Atlantic Fleet.

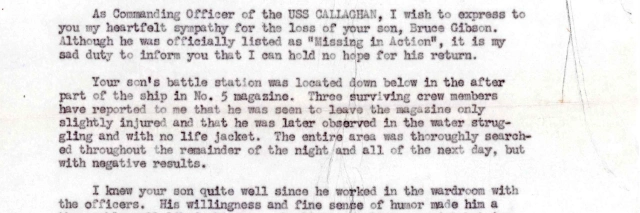

The attack on Pearl Harbor meant that the battleship was more urgently needed in the Pacific, though Seaman 2nd Class Henderson was able to join her crew at the Receiving Station, Norfolk, Virginia, on December 18, 1941.

It did not take long for Seaman 2nd Class Henderson to get into trouble aboard his new ship. He was A.O.L. for two days and 18 hours during December 28–31, 1941. This time, he was tried by deck court-martial on January 16, 1942, and sentenced to 10 days’ confinement and to lose $18 of his pay.

In early 1942, after finishing an overhaul at Portsmouth, Virginia, Mississippi set sail, transiting the Panama Canal and arriving at San Francisco, California, on January 22, 1942. Two days later, Seaman 2nd Class Henderson was warned for being 20 minutes late for muster. Finally, on the morning of February 15, 1942, Henderson was reported A.O.L. yet again, returning to his ship nearly 24 hours late.

The American armed forces were rapidly expanding in the months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, but the Navy had had enough. On February 21, 1942, Seaman 2nd Class Henderson was informed that he was being given an undesirable discharge from the U.S. Navy. He declined to give a statement in his defense. The explanation in Henderson’s personnel file, attributed to Mississippi’s commanding officer, Captain Jerauld Wright (1898–1995), was blunt:

Has committed repeated petty offenses not seriously sufficient for court martial. Unable to maintain himself or his clothing in presentable condition. Loss of clothing and bedding which constantly requires supervision. Unable to perform simple assignments without assistance and supervision. Not amicable to discipline[.]

The Navy gave Henderson his last month’s pay, $25, as well as a $166.70 travel allowance to cover his transportation expenses from San Francisco back to Philadelphia.

U.S. Army Training & Marriage

When he registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, Henderson was living with his grandmother in Bivalve and working for the Stowman Bros. in Port Norris, New Jersey. At the time, the registrar described him as standing five feet, eight inches tall and weighing 156 lbs.—suggesting he had gained both height and weight during his Navy stint—with blond hair and blue eyes.

It appears that Henderson briefly returned to Delaware shortly thereafter. An article in Journal-Every Evening stated that Henderson lived with his aunt, Rose L. Taylor, in Minquadale and worked at the Pusey & Jones shipyard in Wilmington before entering the U.S. Army. Indeed, a note on his headstone application by an official stated that Henderson entered the service from Delaware rather than New Jersey.

Despite the way his naval career ended, Henderson was drafted into the U.S. Army in the spring of 1943. The headstone application indicates that he was inducted on April 8, 1943, and went on active duty on April 15, 1943. Very little is clear about the early part of his Army career. A payroll record indicates that after attending basic training, Henderson volunteered for airborne training. Effective September 7, 1943, he qualified for extra pay as a parachutist. If not before, by September 15, 1943, he was a member of the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment at Camp McCall, North Carolina. On that day, he was convicted in a summary court martial for an unknown offense and forfeited $33 of his pay.

Effective October 27, 1943, Private Henderson’s jump status was revoked. The same day, he went A.W.O.L. It is unclear in the payroll record whether he went A.W.O.L. after his jump status was terminated or whether it was revoked due to him going A.W.O.L. While on the lam, on November 15, 1943, Henderson married Mary S. Ellis (1921–2000) in Wilson County, North Carolina. His bride was a resident of Stantonsburg, North Carolina. On November 30, 1943, Henderson was apprehended or turned himself in, and was placed in confinement in Atlanta, Georgia. He was forced to pay for his own travel and subsistence expenses to Bringhurst, Louisiana, and the roundtrip expenses of his guard or guards.

On January 4, 1944, Private Henderson was transferred to the 84th Infantry Division (the “Railsplitters”) at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. He went A.W.O.L. again during January 12–17, 1944. He was assigned to the 84th Infantry Division’s 333rd Infantry Regiment on January 26, 1944.

On January 31, 1944, Private Henderson joined Company “K,” 333rd Infantry Regiment, 84th Infantry Division. On February 5, 1944, the punishment for his misbehavior was announced: Henderson forfeited $18 of his monthly pay for six months.

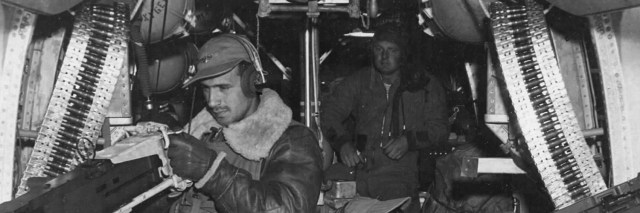

Private Henderson was assigned to 4th Platoon (Weapons Platoon), Company “K,” 333rd Infantry Regiment, 84th Infantry Division. Jim Sterner (1923–2024), another member of 4th Platoon, recalled that Henderson was a member of a machine gun squad in the light machine gun section.

A company 1944 morning report listed Henderson’s Military Occupational Specialty (M.O.S.) code as 745. 745s were most commonly riflemen, but under the tables of organization in effect by that time, the only 745 in the light machine gun section should have held the duty of messenger. However, discrepancies between morning report M.O.S. codes and the tables of organization are extremely common. In the case of a soldier from another machine gun squad in a rifle company weapons platoon in the Pacific Theater, Private 1st Class Joseph F. Maczynski (1920–1945), multiple eyewitness statements agree that Maczynski was an ammunition bearer in a light machine gun squad. However, like Henderson, a morning report listed Maczynski’s M.O.S. code as 745.

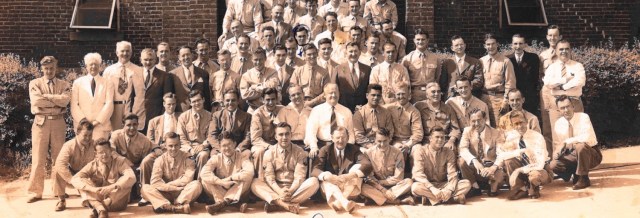

Sterner described Henderson as a “rough, tough young man.” He stated that Henderson was “so strong and muscular, he could do a one-armed push-up with a full field pack on.” Evidently, he had matured since his stint in the Navy, since Sterner did not recall Henderson ever being disciplined.

On September 4, 1944, Henderson’s unit left Camp Claiborne for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, by train. Kilmer was a staging area for the New York Port of Embarkation. On September 20, 1944, the unit shipped out from New York aboard the U.S.A.T. Edmund B. Alexander.

Combat in the European Theater

Company “K” arrived in Normandy, France, on November 2, 1944. They moved northeast by ground across France and Belgium towards the front lines near the German border. Though well trained, only one soldier among its six officers and 196 enlisted men had prior combat experience. The company entered combat for the first time during the assault on the Geilenkirchen salient known as Operation Clipper. The area had a significant number of fortifications, part of the network of German border defenses known to the Allies as the Siegfried Line.

In their book, The Men of Company K: The Autobiography of a World War II Rifle Company, Harold P. Leinbaugh and John D. Campbell wrote that “Although part of the American XIII Corps and the Ninth Army, the Railsplitters for their first battle came under the operational control of the experienced British XXX Corps, commanded by Sir Brian Horrocks.”

1st Battalion, 333rd Infantry Regiment led the assault into Geilenkirchen on November 19, 1944. 3rd Battalion (including Company “K”) was initially in reserve. When they followed, they encountered only demoralized Germans, most of whom surrendered with little resistance. In their book, Leinbaugh and Campbell wrote that “While K Company was mopping up in Geilenkirchen, Baker and Charlie companies were pressing forward another mile, only to meet strong resistance at the edge of Suggerath. Fire from pillboxes and machine-gun nests brought their attack to a standstill.”

At midday on November 21, 1944, Company “K” advanced northeast, with armored support from the British Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry. The company captured an estate, Schloss Leerodt (referred to as Château Leerodt in The Men of Company K), but German resistance stiffened immediately past it, making it impossible to advance further.

After regrouping, Company “K” launched a new attack at 1600 hours, which made only a little headway before bogging down under heavy German mortar and machine gun fire. In The Men of Company K, Leinbaugh and Campbell wrote:

Men began digging but struck water just below the surface. “An overpowering feeling of fear and of despair enveloped me as I tried to bail water out of the hole with my helmet,” [Ed] Stewart recalls. “The shells continued to explode in the midst of us. It was dark and cold and miserably wet. We were taking terrific punishment.” Finally word came whispered down the line to pull back.

Company “K” returned back to Schloss Leerodt but endured a night of enemy mortar fire. In their book, Leinbaugh and Campbell quoted Howard Broderick:

Henderson and I were teamed up, but for some reason he wouldn’t help [dig a foxhole]. Heavy shelling hit our area, and Henderson got in the hole with me, but it bothered him so much he hadn’t helped dig that he climbed out and took his chances.

Miraculously, Henderson was not hit. His luck did not hold the following day.

As Jim Sterner recalls it, on November 22, 1944, Company “K” pushed forward again, crossing the river Würm and entering Müllendorf. Sterner described it as being “about six houses…it was a tiny little village.”

Müllendorf was well fortified, however. Sterner was in a small group of machine gunners and mortarmen who came under fire from a nearby enemy pillbox. Sterner stated that they sought shelter in a narrow alleyway. The alleyway was only about four feet across, so the men were in one line, with just a “brick wall between us and the Germans.” Coincidentally, three men from the Wilmington area were in a row: Sterner, Donald Stauffer, and Henderson.

Sterner recalls that suddenly, a German artillery shell, probably an 88 mm, blew a hole in the wall. Henderson bore the brunt of the explosion and was killed instantly. At least two other men from the machine gun section, Claudie Daniell and Robert Krieger, were wounded.

Sterner’s close friend, Don Stauffer (1924–2014), was quoted in The Men of Company K with a similar version:

An 88 hit the wall right next to Sterner and myself and then a mortar shell came in a few feet from the two of us—that was the one that got Claudie Daniell, our machine-gun section leader, and killed Henderson.

Howard Broderick also attributed Henderson’s death to a mortar shell. Sterner recalls that at the time that an 88 mm and mortar shells were landing in close succession, but that he is certain that based on Henderson’s wounds, it was the 88 that killed him.

The 333rd Infantry Regiment after action report stated of that day:

The attack continued at 1100A 22 November 1944, the pill-boxes along the SUGGERATH-WORM road which had delayed the advance the preceding being reduced by the employment of doughboys from the 2d and 3d Battalions against the blind side of the pill-boxes. The attack progressed to a line on the high ground approximately 300 yards south of MULLENDORF, where, at 1830 22 November 1944, the Regiment was ordered to hold and consolidate its present positions, although elements of the regiment had succeeded in entering the town.

The attack was ultimately unsuccessful. On November 23, 1944, the day after Private Henderson was killed, 3rd Battalion headquarters ordered Company “K” to withdraw about one mile back to Süggerath. Company “K” casualties during its first five days of combat were severe. Leinbaugh and Campbell wrote that “twelve or thirteen men had been killed and at least forty wounded. Thirty men had been sent to the rear with trench foot. A dozen more were simply missing.” Some of the missing eventually returned to friendly lines, with the rest eventually confirmed dead or captured.

Henderson was buried in a temporary cemetery. After the war, his body was repatriated to New Jersey. After a funeral service in Port Norris on May 22, 1949, presided over by the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion, Private Henderson was buried in the Cedar Hill Cemetery in nearby Cedarville. Henderson is honored on the New Jersey section at Veterans Memorial Park in New Castle, Delaware.

Notes

Middle Name

Various records spell Henderson’s middle name as Dubois or DuBois. His signatures on different documents use both spellings.

Place of Birth

Henderson’s U.S. Navy personnel file gave his place of birth as Cedarville, New Jersey. The file stated this was verified “by birth certificate issued by Commercial Township, Cumberland County, New Jersey.” His draft card listed his place of birth as nearby Bivalve, where he later lived. Interestingly, Bivalve is in Commercial Township whereas Cedarville is in Lawrence Township—at least as of 2023. Notwithstanding the discrepancy, the towns are only about 12 miles apart, both located in Southern New Jersey near Delaware Bay.

Brother’s Name

Different sources give Henderson brother’s name as John Griffith Henderson, Jr. or John Edward Henderson, with the latter more common.

Time in Delaware

It is not clear when Henderson left Delaware as a child. When his mother died in Wilmington in 1935, her obituary stated that John Henderson and his sons were living in Bivalve. Henderson must have returned to Delaware at some point to work at Pusey & Jones, most likely between the time he registered for the draft in New Jersey in June 1942 and when he was drafted there in April 1943. There was a Rose Taylor living in Minquadale recorded on the census on April 3, 1940, probably the aunt he lived with while working at Pusey & Jones. Despite that, Henderson listed his residence as Bivalve, New Jersey, on his marriage certificate. His name is also on the New Jersey section at Veteran’s Memorial Park in New Castle and his name appeared on the Cumberland County, New Jersey, casualty list.

Start of U.S. Army Career

Private Henderson is one of approximately 13% of World War II era U.S. Army soldiers whose enlistment data card could not properly be digitized by the National Archives. A government official made edits to a headstone application submitted by his father or brother in 1949, listing Henderson as joining the service on April 8, 1943 (presumably his induction date) and adding that he went on active duty on April 15, 1943. The official also crossed out New Jersey for his state and added Delaware, showing that he was a resident of Delaware at the time he was drafted.

Wife’s Middle Name

Mary S. Ellis’s middle name was listed as Sallie on her marriage certificate to Henderson, but Sally on other sources. On September 20, 1947, she remarried in Lynchburg, Virginia, to a sailor, Jimmie Oliver Vernon.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the late Jim Sterner for providing information that made this article possible, as well as some of the photos accompanying it. Thanks go out as well to Rick Bell for providing 333rd Infantry Regiment documents and to Lori Berdak Miller at Redbird Research for Henderson’s final pay voucher.

Bibliography

Applications for Headstones, January 1, 1925 – June 30, 1970. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/40050_644066_0004-02499

Applications for Headstones and Markers, July 1, 1970 – September 30, 1985. Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2375/images/2375_12_01006-04393

Certificate of Birth for John Edward Henderson. Record Group 1500-008-094, Birth Certificates. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YQM-Q8W3

Certificate of Death for Ruby Taylor Henderson. Delaware Death Records. Bureau of Vital Statistics, Hall of Records, Dover, Delaware. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6L6S-9R3

“Donald F. Stauffer.” The News Journal, March 8, 2014. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-news-journal-don-stauffer-obit/137743502/

Draper, Theodore. The 84th Infantry Division in the Battle of Germany November 1944–May 1945. The Viking Press, 1946. https://archive.org/details/84thInfDivBattleOfGermany

Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4531892_00963

Final Payroll Record for Robert D. Henderson. November 30, 1944. Individual Pay Vouchers, c. 1926–1963. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Lori Berdak Miller.

“Henderson, John E.” The Press of Atlantic City, August 3, 2000. https://www.newspapers.com/article/137677571/

“Killed In Action.” Millville Daily Republican, December 27, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/79135269/henderson-kia/

Leinbaugh, Harold P. and Campbell, John D. The Men of Company K: The Autobiography of a World War II Rifle Company. William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1985.

“Military Funeral For Pvt. Robert D. Henderson.” Millville Daily Republican, May 23, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/79136235/henderson-funeral/

Morning report for Company “K,” 333rd Infantry Regiment. December 10, 1944. U.S. Army Morning Reports, c. 1912–1946. Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

Muster Rolls of U.S. Navy Ships, Stations, and Other Naval Activities, January 1, 1939 –January 1, 1949. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32861_250806-00117, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1143/images/32861_250806-00217

North Carolina Marriage Records, 1741–2011. Record Group 048, North Carolina County Registers of Deeds. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, North Carolina. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/60548/images/42091_343648-00374

“Obituary Notes.” Wilmington Morning News, October 4, 1935. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/79139111/ruby-taylor-henderson/

Official Military Personnel File for Robert D. Henderson. Official Military Personnel Files, 1885–1998. Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri.

“Pvt. R. D. Henderson Services To Be Held.” Wilmington Morning News, May 20, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/78711926/private-robert-d-henderson/

“Pvt. Robert Henderson.” Journal-Every Evening, May 19, 1949. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/79135733/robert-henderson-service/

Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Record Group 29, Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9M1-RJBF

Sterner, Jim. Phone interviews on May 31, 2021, and December 9, 2023, and interviews on June 8, 2021, and June 13, 2021.

“Summary of Operations U.S.S. Mississippi period December 7, 1941 to March 31, 1942.” World War II War Diaries, 1941–1945. Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. https://www.fold3.com/image/270451437

“Table of Organization and Equipment No. 7-17: Infantry Rifle Company.” War Department, February 26, 1944. Military Research Service website. http://www.militaryresearch.org/7-17%2026Feb44.pdf

Timm, Loren J. “After Action Report [333rd Infantry Regiment] for the period 1 through 30 November 1944.” Courtesy of Rick Bell.

Virginia Marriages, 1936–2014. Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9279/images/43067_162028006056_0528-00342

World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6482/images/005217864_05126

WWII Draft Registration Cards for New Jersey, October 16, 1940 – March 31, 1947. Record Group 147, Records of the Selective Service System. National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2238/images/44025_05_00035-01585

Last updated on April 1, 2025

More stories of World War II fallen:

To have new profiles of fallen soldiers delivered to your inbox, please subscribe below.